At Fifty, Remodeling for Equity

MCA Chicago

The Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA Chicago) occupies a premier location in Chicago’s downtown. Situated in the city’s historic Gold Coast, one of the most affluent neighborhoods in the country, the museum is buffered by two public parks, which grant it a view of Lake Michigan.[1] It is the largest contemporary arts museum in the country, with around 140 full-time and 200 part-time staff, and almost 3,000 works in its permanent collection.

In 2017, MCA Chicago celebrated its 50th anniversary with a remodeling of its public spaces and a three-part exhibition drawn from its permanent collection titled We Are Here. The museum’s new features fit with its current vision statement—to be an “artist activated, audience engaged” environment.[2] A commitment to fostering visual literacy and citizenship connects both artist and audience in a building that lends itself to contemplative, social, and educational experiences. “Here we create citizens, not consumers,” Pritzker Director Madeleine Grynsztejn says of the museum. A shift in attention toward the experience of the visitor has created opportunities for connection between artists and broader social issues.

In recent years, the museum has taken active steps to diversify its program, staff, audience, and board, a process essential for MCA Chicago to more closely reflect and understand Chicago’s communities. It has developed a culture of inclusion, accessibility tools that serve the broader field, and unique organizational structures to improve equity for artists, audiences, and staff. But MCA Chicago still faces some barriers to realizing equitable practices internally. It also has further work to do to connect its programs more explicitly with underserved communities. MCA Chicago’s mindful efforts, but also its remaining barriers, make it an important museum to examine as other institutions consider issues of diversity, inclusion, and equity.

Key Findings

The site visit to MCA Chicago included interviewing ten MCA Chicago staff and board members, observing meetings, and attending public events. Over the course of three days, several key findings emerged that may be relevant to the broader field.

Cultivating Alignment: At MCA Chicago, staff have made progress toward realizing the values of access, inclusion, and equity across departments and levels of seniority. Rather than achieving this through a hierarchical approach, leadership has empowered grass-roots action through invested staff members across the institution, inviting experimentation within and across departmental contexts.

Breaking down silos: To bridge gaps between disconnected stakeholders, MCA Chicago has experimented with a new committee model, the creation of a new position to liaise across departments, and the structuring of opportunities for leadership to listen to museum staff across levels of seniority.

Diversifying Collections and Exhibitions: In its collection development, the museum seeks to embrace global perspectives and also to support Chicago’s legacy in the visual and performing arts. It has taken active steps to diversify its collection.

Challenges and Tradeoffs

We also observed challenges to increasing inclusion, diversity, and equity in the museum.

Internship program: Although the museum’s valuable internship program now recruits less from elite institutions and increasingly from more diverse pools, it has been unable to fund the bulk of its internships. Unpaid internships create a barrier to entry for low-income candidates.

Beyond the walls: In a highly segregated city, partnerships with grass roots arts organizations in underserved neighborhoods have helped MCA Chicago to serve disenfranchised communities. It has not yet been possible for the museum to make the investments necessary to grow and sustain a full set of such partnerships to serve the entire city and region.

History and Context

MCA Chicago was founded in 1967, a year before the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. which sparked perhaps the most severe level of social unrest during the 20th century in the U.S.[3] Tensions were particularly high in Chicago, where the protests of the Democratic National Convention led to unprecedented violence. The museum responded to these social forces with an exhibition: Violence! In Recent American Art, signaling to some degree the museum’s early interest in responding to the pressing matters of its time.[4]

By 1968, racial tensions in Chicago were deeply entrenched. The city’s history is marred with policies and bureaucracy that intended to segregate and exploit minorities, an activity deeply connected to migration patterns of African Americans fleeing the South.[5] The effects of these policies are still felt today. The Great Migration resulted in an increase in the African American population from less than five percent to roughly one-third of the city’s population by 1970. In the 1927 case Corrigan v. Buckley, the Supreme Court granted what amounted to legal cover for segregationist real estate practices, opening the door to racially restrictive covenants. Advocated by the Chicago Real Estate Board, these explicitly specified which races were able to buy houses in certain neighborhoods and established many of the racial divisions that persist across the city.[6] Chicago is, by some measures, considered the most segregated major city in the country.[7]

Today, Chicago has the third largest creative economy in the U.S., generating an economic impact of over $2 billion a year, and employing over 150,000 people.[8] From jazz and blues to house and hip-hop, the city has been home to some of the most innovative and virtuosic American musicians in history, heavily influencing commercial music trends in the country. Collectives such as the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians in Chicago’s South Side continue to foster this tradition.

Like many cities in the northern U.S., Chicago’s population has declined steadily over the last fifty years, from 3.6 million in the 1960s to roughly 2.6 million presently.[9] Chicago has a Latinx population of 29 percent, a black population of 32 percent and a white population of 32 percent, making it among the most diverse cities in the U.S. High degrees of diversity and segregation also correspond with socioeconomic inequities. Since 2000, the average incomes of black and Hispanic city residents have decreased while average incomes of whites have steadily risen.[10] Segregation by neighborhood often translates into limited access to the city’s rich cultural resources, many of which, such as the MCA Chicago, are concentrated in the affluent downtown. As a result, Chicago’s 2012 cultural plan calls for building “connections to and cross-pollination with other areas of the city.”[11] The plan challenges cultural organizations in Chicago to find, “a way to further expand the value of major events beyond downtown,” asking: “How can existing resources and policies strengthen cultural experiences across and between Chicago neighborhoods?” But it can be difficult to counter a history of structural racism, particularly when it results in limited physical access to cultural resources, a challenge with which many arts administrators continue to struggle.

Staffing and Committees

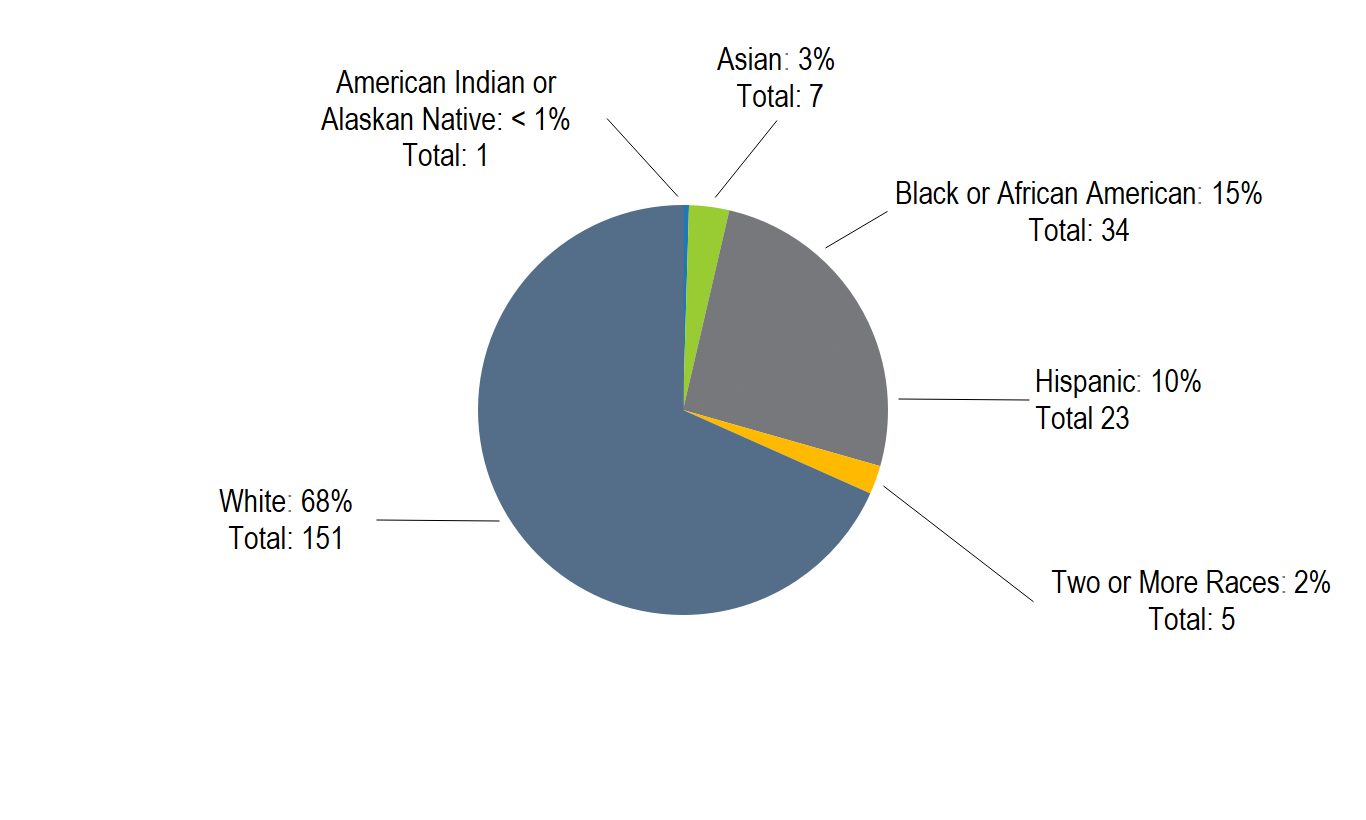

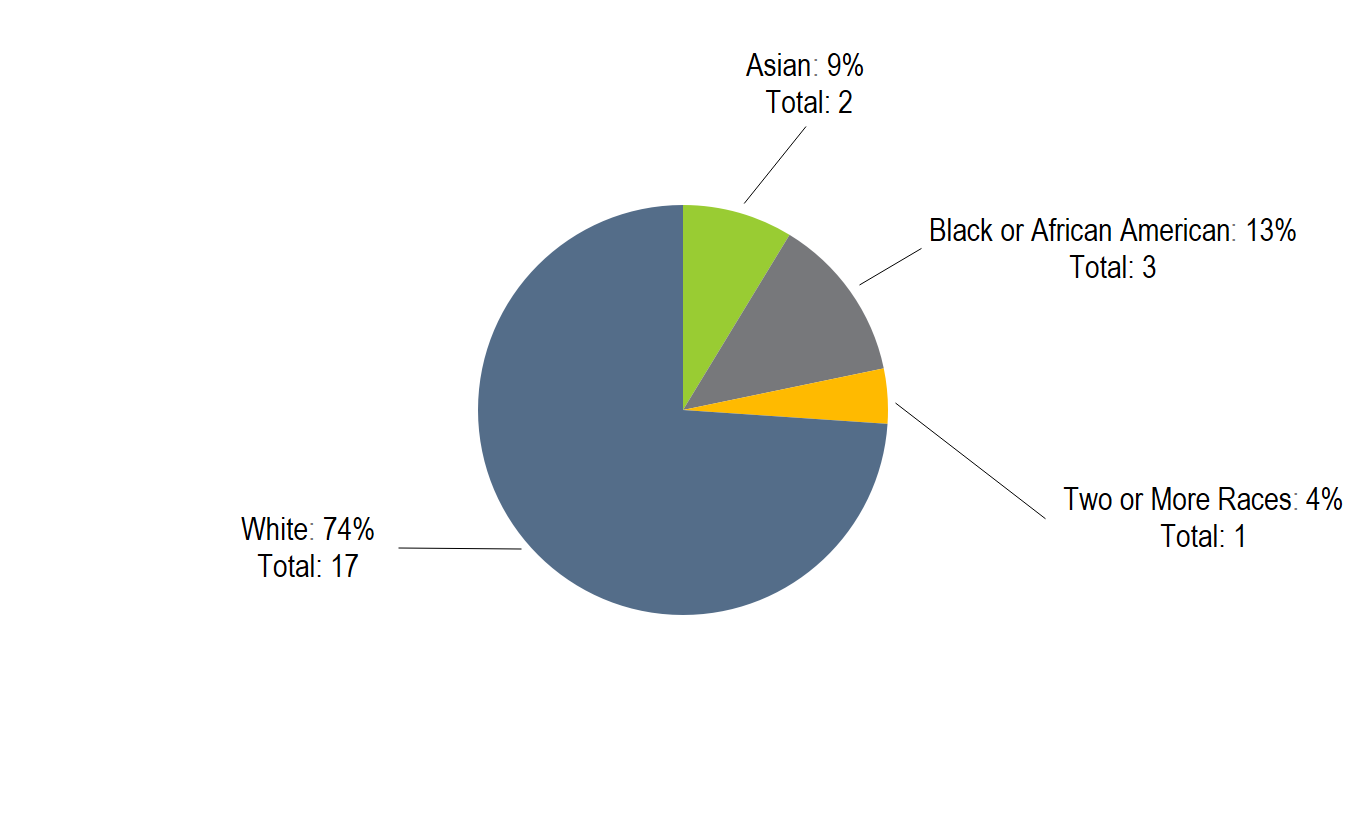

In The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation’s 2015 survey of museum staff demographics, MCA Chicago was one of the most racially diverse institutions among curatorial, education, conservation, and senior administration positions, particularly in the Midwest.[12] Overall, MCA Chicago staff were 32 percent people of color, with 26 percent people of color working in intellectual leadership roles. While the overall staff was not much more diverse than the national average (28 percent POC), intellectual leadership positions were substantially more diverse compared to the national average of 16 percent. This data suggests that the barriers to entry in these fields may be lower for people of color at MCA Chicago than elsewhere in the sector, or that MCA Chicago retains staff of color more effectively.

Figure 1: MCA Chicago All Staff

Figure 2: MCA Chicago “Intellectual Leadership” (Educators, Curators, Conservators and Senior Administrators)

At the board level, the museum is relatively more diverse than AAMD museums that participated in the 2015 survey, with roughly three times the number of African American trustees (14 percent).

Commitment Out of Crisis

The current diversity on MCA Chicago’s board has been the result of deliberate efforts, stemming from a difficult incident eighteen years ago in which four women of color resigned from the board in unison following a moment of cultural insensitivity.[13] This exodus dramatically changed the museum’s relationship to diversity issues, under the leadership of then director Robert Fitzpatrick. “It was a blessing,” says Angelique Power, former director of communications and community engagement at MCA Chicago and current president of the Field Foundation. “It sent a shudder through the institution. I think if it didn’t send shudders through most museums it should have.” Board members Martin Nesbitt and Steve Berkowitz spearheaded the formation of a committee to address the clear challenges the museum faced in improving relations with underrepresented groups. From this effort, an Audience Development and Diversity (AD&D) committee was established—a group of MCA Chicago trustees and patrons of color in Chicago who offered their time to help MCA Chicago think about audience diversity and tap into the communities of color that they were not reaching. For over a decade AD&D was housed in the marketing department, focusing on programming, communications, and exhibitions—the outward facing elements of the museum. While this committee was disbanded in 2012, it was instrumental in forming two key programs: an annual public talk about diversity and inclusion in the field, called “The Dialogue,” and “Tuesdays on the Terrace,” a live jazz event that brings a diverse, multigenerational crowd to the museum every Tuesday evening throughout the summer.

These programs reflect the ongoing impact of the committee. But many at the museum feel the AD&D program failed to deliver a necessary transformation. Board member Marquis Miller describes this as a period when diversity was treated as a “sixth finger” in the institution—tangential to the central matter of presenting contemporary art—whereas now it has become “integral to the forward-looking aspect of the museum’s work, internally and externally.” This is in no small part the result of Grynsztejn’s efforts. From her perspective, the AD&D committee failed to do something crucial: to allow the institution to reflect and cultivate further its own relationship to issues of equity, diversity, and inclusion. As she sees it, this failure came from a combination of two factors. First, the committee’s focus was entirely program-driven, ignoring diversity and inclusion on the staff and board. Second, the committee was not well aligned or integrated with other museum departments. By delegating the committee to the marketing department, there was a sense that one part of the museum was doing something about diversity issues while letting others off the hook.

Grynsztejn disbanded the AD&D committee four years into her directorship, in spite of her strong commitments to diversity issues. “You don’t kill off a committee and not worry about it,” she said, describing it as a risk. “I think the hardest thing for people to see in institutions is when something has died on the vine.”

Shortly after the AD&D committee was disbanded, another moment of cultural insensitivity at the board level sparked conversations about developing a task force to continue addressing some of the issues AD&D was concerned with, but with a crucial difference—looking inward to understand the organization’s relationship to its values, as well as outward towards visitors. Grynsztejn and newly appointed chief operating officer Teresa Samala de Guzman established the Access, Inclusion and Equity task force. This task force is still in place, and is housed in the office of the director.

Relative to the marketing department’s Audience Development and Diversity committee, the Access Inclusion and Equity (AIE) task force has an expanded mission to promote inclusivity in staffing and create pathways for diverse candidates to enter the field. But the structure of the task force is as significant as its expanded mission. AIE is composed of roughly a dozen members, half of whom are staff and the other half trustees. Each board member is paired with an employee. In this way, the AIE task force bridges a gap between staff and board, allowing for a more natural exchange of ideas and alignment around attendant issues. “That was [de Guzman’s] master stroke,” board member Marquis Miller explains. From Miller’s point of view, there are still some dismissive attitudes toward these efforts on the board, an artifact of “their vintage,” he says, “but also because they are relatively removed from the way the rest of the world works.” Part of the value of the AIE task force is to create alignment between staff and board around the evolving discourses related to access, equity, and inclusion.

De Guzman started this process with a listening tour. She set up informal talks with much of the museum staff, an effort that not only helped her understand the appetite for such an initiative internally, but also helped staff think about ways they could contribute to the museum’s progress toward being a more accessible resource. “The call to action was that all of us can do this. Each of us can make this a reality for all of us. Whoever you are, you can start something,” she said. An important part of forming this task force included advocating for everyone in the museum to consider their work in relation to access, inclusion, and equity, and thereby catalyze efforts across the organization, instead of creating yet another siloed initiative. Formally, this has resulted in an ongoing program called the Brown Bag series, in which staff gather to discuss issues at the MCA Chicago across departments and levels of seniority. These discussions reflect Grynsztejn’s interest in catalyzing action around the shared values of access, inclusion, and equity at every level in the museum.

Grynsztejn thinks this effort has been successful: “Everyone understands philosophically that it’s at the heart of what we do. If I’d given it to any other departments, automatically that person would be responsible for AIE in the whole building.” She described how paradoxical it is to generate momentum with AIE initiatives. While it is essential for the initiative to be spearheaded by the director, “the way that it succeeds is if it is owned at the flattest managerial level by as many people as possible. The success comes when you open the door to who wants to own it. They will have my green light and the MCA’s money. But the idea won’t have come from me. It’s actually quite important that it not be top down.”

MCA Chicago serves as an interesting example of the merits and drawbacks of approaching the challenges of equity, diversity, and inclusion with committee structures. In some cases, the structure of the committee can reflect the institution’s relationship to these values. The AD&D’s outward facing approach seems now to be a product of the multicultural discourse of the 1990s, which often failed to look at making necessary internal changes. The AIE committee reflects not only an inward turn, but also a horizontal structure, more reflective of the emergent discourses around inclusion and equity that have shaped current perspectives on these values.

Naomi Beckwith, curator at MCA Chicago, explained that AIE had some significant impact at its inception. Most importantly, it led the museum to move toward free admission for everyone under 18. However, she acknowledges that the committee is somewhat unsure of its next move: “We’ve stalled a little bit, and that stalling has come from wanting to do well but not knowing how to do well. We’re still looking for that node, for what it is that we need to be doing. Whatever we end up doing needs to be inward facing and outward facing.”

It may be that Beckwith’s observation has to do with the non-hierarchical design of the task force. A democratic approach can be slow, as consensus develops. However, top-down directives have their own drawbacks; they are more likely to breed resentment, and it is often difficult to identify a “node” as Beckwith says, without allowing for discourse across departments and levels of seniority. Within the structure Grynsztejn has established, individuals are empowered to pursue the values of access, inclusion, and equity from their own perspectives. At the moment, for example, one AIE member is pushing her vision for a paid internship program and is beginning to gain traction.

Internship Program

The issue of unpaid internships in the arts sector has been an ongoing source of concern in the field.[14] In a sector that often excludes the disadvantaged implicitly through networks of privilege, unpaid internships pose a financial barrier for those who cannot afford to work for free. This issue is exacerbated in the current economic climate; while Americans reach median earning levels later in life than ever before, college debt continues to rise, increasing over five times in the first decade of the twenty-first century.[15]

MCA Chicago takes great pride in its internship program, which provides students and young professionals with valuable experience with the museum’s operations. Indeed roughly 20-30 percent of full time staff at the museum began as interns. But many employees recognize that the program will be exclusive as long as it remains unpaid. The internship program operates on a three-term schedule with 15-20 interns per term. “It’s not getting coffee,” assistant director of human resources Erica Denner says, adding that if they were able to shift to paid internships she thinks it would be one of the best programs in the country. Denner is paired with board member Marquis Miller on the AIE task force, and would like to prioritize paying all interns in the program. At the moment only two interns per year receive financial support. Recently, the museum has shifted away from recruiting from more selective institutions, such as Ivy League schools, to local state institutions, resulting in a notable demographic shift, according to Denner. While certain board members have offered to fund the internship program for the year with a contribution of a few hundred thousand dollars, Grynsztejn rejected the offer. “I’m not going to fund the program for one year and then take it away from them. It needs to be endowed.” The cost of endowing the internship program is roughly four million dollars, as of 2017. Grynsztejn fears that by accepting funding for a single year, the temporary victory will kill the momentum toward a more permanent solution. “When we move toward paid internships, we want to make sure it’s a permanent feature of the museum,” Grynsztejn said, adding that this has been their policy toward other access initiatives such as free under 18, and free admission on Tuesdays for Illinois residents. In the meantime, Denner is working toward removing financial barriers for interns by matching them with external funding sources. It remains to be seen whether this strategy will yield a funded internship program in the future, or if the museum will struggle to generate enthusiasm among donors for endowing positions that are traditionally unpaid.

The need for this change is felt acutely among staff. Claire Ruud, director of convergent programming, described the importance of showing support for access, inclusion, and equity values with funding: “If you don’t put money behind it, it’s not going to happen. If we want a more diverse intern pool, we need to pay interns. If we want to recruit more broadly across the city, we need to put more money into recruiting.” Many staff shared the perspective that the museum is making significant steps, but still has far to go.

Accessibility

One example of a success that has emerged from horizontal engagement with access issues is Coyote, an open-source, collaborative software program developed by the MCA Chicago that helps to create text descriptions of images. It was developed from a desire to have a website that reaches the highest level (AAA) conformance to web content accessibility guidelines, in order to, for instance, allow screen readers to describe images to blind or sight-impaired audiences.[16] Sina Bahram, founder of Prime Access Consulting, collegially challenged Susan Chun, chief content officer, by suggesting it wasn’t possible for a museum site to get the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines’ AAA rating, given the number of images on the site. Then they got to work. Chun and Bahram collaboratively built a software program for textual image description. They relied heavily on the museum’s staff to crowd source the descriptions. Toward the end of 2017, MCA Chicago had described 1,752 images, while 1,350 have been approved but not yet published, out of a total of 14,813 images. Bahram approves of the effort MCA Chicago’s staff make toward designing their facility to be as accessible as possible, celebrating their “query-based way of looking at accessibility and inclusive design—of [asking], ‘How can we do this better?’ and iteratively failing forward, and not being afraid of actually trying things and then improving upon that based on visitor feedback or expert feedback or research in the field.”[17] Coyote, a successful example of this approach, has since received a grant from the Knight Foundation to expand the accessibility software.

Accessibility has long been a central focus of MCA Stage, the museum’s performance program, which operates from the Edlis Neeson Theater. Manager of performance programs John Rich shared the thoughtful approach the museum has taken to accessibility issues in its performance programming, both in terms of accommodations and content. Rich explained that the museum has embraced relaxed performances, which take into account the lighting, space, and noise in a way that maximizes access for people with disabilities. In relaxed performances, audience members are able to come and go from a performance without being disruptive. While the dynamic between the performers and audience is different, the content remains the same. Rich says of these efforts, “Doesn’t access just make every show better? And I feel that everyone in the department strongly feels this way. The more that we do it the more it’s made to feel like part of a regular theater experience.”

In some cases, the performed material has also addressed issues of accessibility, challenging traditional notions of beauty and sexuality. For instance, Julie Atlas Muz and Mat Fraser’s Beauty and the Beast, the product of a commission by the Extravagant Bodies Disability Arts Festival in Croatia, offers audiences an intimate view into the psychology and physicality of people with disabilities. Muz describes the adapted fairytale as having strong adult themes related to disability issues, therein providing a point of access for broader audiences.[18] She says the work shares “insider” knowledge about disability, beauty, and sexuality with audiences.

Rich shared some useful lessons MCA Stage has learned in producing performances with accessibility in mind. For instance, he described a concern that some have of the “ghettoization” of accessibility shows. By this he means grouping together all of the accessibility efforts for a single performance, rather than offering sign language one night, relaxed performance another, for example. “For some, providing access for one show, it can seem like a form of marginalization. But this isn’t the vibe in Chicago, because when you separate access offerings, people with different disabilities can’t see the same show together, and people in Chicago have expressed they want the experience of seeing a show together.” Rich explained that central to MCA Chicago’s new understanding of access offerings was a partnership with Bodies of Work, a Chicago based network of artists and organizations, which serves as a “catalyst for disability arts and culture that illuminates the disability experience in new and unexpected ways.”[19] With guidance from Bodies of Work, the MCA Chicago has been able to address some of the needs of the disability community in Chicago.

Relaxed performances don’t cost MCA Stage more, thanks to a student volunteer program with the University of Chicago, but they do much to signal a welcoming environment to people with disabilities. And as Rich sees it, they add another layer to the performance for everyone in attendance: “Relaxed performances are more fun because you can feel encouraged to make rejoinders and shout out and be more expressive regardless of who you are. That’s another kind of a risk that we take.” MCA Stage’s willingness to listen and adapt to the needs of those with disabilities has done much to make the museum more welcoming.

Remodeling for Values

Coinciding with its fiftieth anniversary, MCA Chicago has completed a renovation that elevates communal spaces in the museum.

Chris Ofili, The Sorceress’ Mirror, (2017), Photo: Kendall McCaugherty, © MCA Chicago

Designed by British painter Chris Ofili and featuring a prominent mural, The Sorceress’ Mirror, the museum’s new restaurant, Marisol, aims to extend a rich aesthetic experience to a new entry point. Near the restaurant, a private room is intended to make the museum more inviting for those who require a private space for prayer. “I can’t truly welcome a person who practices [Islam] if I don’t offer them a place to pray,” Grynsztejn said. The room may also be used by staff and visitors for meditation or lactation.

While the double-height ceilings of the former restaurant have been sacrificed, in their place MCA Chicago has constructed two new centers for social and educational engagement. The Commons, featuring hanging plant lamps overhead, reflects the experimental style of the Mexico City-based architecture and design studio, Pedro y Juana. The architects describe their vision for the Commons as, “A social typology of a third space, a place that you frequent outside of home or work. We imagine the Commons as an egalitarian space in constant motion.” More broadly, Grynsztejn sees the museum in relation to this concept of “third space,” derived from Ray Oldenburg’s The Great Good Place, which develops a concept that places aside from work and home are needed for public interaction in healthy societies.[20] Through this lens, the remodel has aimed to establish common areas for public interaction.

Above the Commons is the learning center, overlooking the 55-foot atrium that grants access to the museum’s galleries. This addition reflects a shifting focus toward providing the audience a similar degree of consideration as the artist. The result is a common area with glass walls, visible from the galleries below, where educational programming takes place. The addition includes learning studios with natural light and views of the lake, and a multi-use room, which Grynsztejn intends to use for trustee meetings, adding a level of visibility between visitors and trustees. Grynsztejn is excited by the results: “What has me a little verklempt at the moment is that this is the first time I can see people using this space in the architectural heart of the building. I wanted to see people learning in this space, in the middle of the building—for it to be visible, so we not only create art but ideas and conversation, always through the lens of the artist.” In the redesign, the education wing has a symbolic position, viewing the galleries internally, and Lake Michigan to the east. The new space reflects the access point education offers to those outside the museum.

Architecture aside, MCA Chicago has invested much in its learning and public programs. For instance, the Teacher Institute bring teachers to MCA Chicago for in depth training and professional development, aiming to train educators to develop socially conscious art curriculum for their students. These programs are taught by paid artists who MCA Chicago has partnered with in the past, such as Faheem Majeed, a resident of Chicago’s South Shore, who “draws upon the material makeup of his neighborhood and surrounding areas as an entry point into questions around civic-mindedness, community activism, and institutional racism.”[21]

This, among other education development programs, brings over 100 teachers to the museum for training, making MCA Chicago a rich resource for arts education in the city. Through partnerships with school programs, about 10,000 students visit per year from roughly 150 schools for artist-led tours. One hundred and twenty one of these are Chicago public schools, and of those 92 schools serve student populations that are over three-quarters low-income. One of the initiatives meant to familiarize students with MCA Chicago is the artist-led Multiple Visit Program, which, “Brings common core state standards to life by offering fourth, fifth and sixth grade teachers and students a chance to debate, discuss and connect to works of art through return visits to the museum.”[22] The museum facilitated 328 free buses from Chicago schools last year. It is effectively opening its doors to the underserved in Chicago.

Evan Plummer, director of arts education for Chicago Public Schools, praised the efforts of MCA Chicago’s education department to make itself a resource for Chicago’s public-school system, particularly its partnerships with teachers: “The team there has really made it possible for teachers to feel like they are a part of the museum.” But he also acknowledged that the educational efforts are centered primarily in the museum’s space. Plummer noted the importance of increasing the museum’s extension of its educational resources out of the museum building and into local communities to counter “the art deserts that exist in our city.” He thinks a higher degree of collaboration with grassroots arts organizations working in some of these areas, such as Sky Art, a community arts organization located in the southeast side of Chicago, could help more individuals in underserved communities think of MCA Chicago as their museum, too.[23] Plummer acknowledged that “it doesn’t happen organically.” Deliberate efforts need to be made if the museum is to establish a presence outside of the Gold Coast.[24]

The museum has begun to move in this direction with the School Partnership for Art and Civic Engagement program (SPACE), which invites socially engaged artists to move their studio practices inside Chicago public high schools, turning available spaces into hubs of artistic production and civic conversation by partnering with teachers and principals. Local artists Andres L. Hernandez (involved in the Obama Presidential Center’s interdisciplinary exhibition design team) and Valerie Xanos (artist and educator from southwest Chicago) launched it. They oriented the program around two central questions, “How do we reactivate spaces in which we feel we have no power? And how do we create spaces where young people can be their authentic selves?”

Diversifying Exhibitions and Collection, Globally and Locally

While MCA Chicago was not known until relatively recently as a museum with diverse collecting practices and exhibition program, some efforts were made toward this goal beginning in the 1990s. For instance, exhibitions like Lorna Simpson: For the Sake of the Viewer (1993), Glenn Ligon: Runaways and Narratives (2000), The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945-1994 (2001), and Tropicalia: A Revolution in Brazilian Culture (2006) have offered visitors access to non-European contemporary art over the years. MCA Chicago was the first U.S. museum to organize the one-person show of the Lebanese installation artist Mona Hatoum in 1997 and Kerry James Marshall’s One True Thing, Meditations on Black Aesthetics in 2004.

A more deliberate effort was being made around the time Beckwith was hired. She emphasized a conceptual point in our discussions: while diversifying staff is important, “I don’t think it can be just a numbers game. It also has to be about how you tell a story. It’s not just talking about a singular genius [when curating], but also talking about cultural backgrounds.” As a result of this focus, the MCA Chicago has excelled in producing exhibitions of non-white artists in recent years. With the hiring of Omar Kholeif in 2015 and Jose Esparza Chong Cuy in 2016 a deliberate decision has been made to make a diverse exhibition program central to the museum’s practice.

In some cases, these are part of MCA Chicago’s Global Visions initiative.

The Global Visions initiative supports exhibitions, acquisitions and curatorial activities focused on contemporary artists from the Middle East, South Asia, Africa, and Latin America. The initiative is co-chaired on the board side by former US Ambassador to the UK Louis Susman and new trustee Sheikh Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi, founder of Barjeel Art Foundation, and led on the staff side by a combined curatorial and development team. Global Visions has played a large role in facilitating exhibitions like the upcoming 2019, Many Tongues: Art, Language and Revolution in the Middle East and South East Asia, as well as solo exhibitions by Michael Rakowitz, Otobong Nkanga, and Lina Bo Bardi.

To illustrate in more detail the strides MCA Chicago has taken in acquiring and showing the art of people of color, some noteworthy exhibitions from the last three years are shared below:

- The Freedom Principle—Naomi Beckwith, the Marilyn and Larry Fields Curator at MCA Chicago, co-curated a show along with former MCA Chicago senior curator Dieter Roelstraete, celebrating a Chicago institution that also recently turned fifty, the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM). At a time when jazz was losing its commercial appeal in the mid-sixties, AACM took the opportunity to push the boundaries of the form. This thriving music collective is now internationally renowned, though often unknown and undervalued at home. Beckwith’s exhibition The Freedom Principle, which she describes as her, “ode to the beauty of South Side cultural history and life,”[25] introduces the instruments that were used to form this collective, and the visual and mixed media work that evolved from experimentation and collaborations with groups such as AfriCOBRA, a collective of visual artists, also from Chicago’s South Side. The exhibition made tangible the artistic contributions and heritage of some groundbreaking musicians from Chicago’s Southside. The group still performs occasionally at MCA Chicago.[26]

- Doris Salcedo—In 2015 the MCA Chicago curated the first retrospective of Colombian artist Doris Salcedo’s thirty-year career. Her work, which this summer was on view as an important part of LACMA’s PST: LA/LA exhibition Home, So Different, So Appealing, addresses issues of political violence. She particularly focuses on los desaparecidos (the disappeared), referring to the thousands of civilians who have been abducted by government or paramilitary officials acting with impunity over the course of Colombia’s half-century civil war. This violence is mourned in certain pieces of Salcedo’s art by filling furniture with concrete. She often includes witness statements alongside the works, as part of an extensive research process.

- MCA DNA: Richard Hunt—Richard Hunt, an African American sculptor and Chicago resident, was featured in an exhibition at MCA Chicago in 2014, curated by Naomi Beckwith. He uses bronze and steel to explore abstract expressions, comparing organic and constructed forms. In 1957, MoMA acquired a work of his while he was still a student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and held a retrospective for him at the age of 35. He has completed over 120 major public sculptures across the US.

- BMO Harris Bank Chicago Works: Faheem Majeed—In addition to helping MCA Chicago with the Teacher’s Institute, Majeed, a resident of Chicago’s South Shore, maintains a complex artistic practice including works of sculpture, installation and performance, that connect to his roles as community activist, curator, educator and arts administrator. MCA Chicago’s exhibition, Chicago Works: Faheem Majeed was the artist’s first solo exhibition, and expanded the museum’s reach. Included in the exhibition was an educational opportunity for two alumni of MCA Chicago’s Teen Creative Agency (the MCA Chicago’s intensive youth development program), Kara Franco and Lamar Gayles, to curate an exhibition at the South Side Community Art Center in Chicago, the oldest African American art center in the country, for its 75th

- The Propeller Group—A Vietnamese artist collective based in Ho Chi Minh City, the members (founded in 2006) create art that confronts the relationship between Vietnam and the U.S. The 2016 exhibition was their first major U.S. show. This exhibition, curated by Naomi Beckwith, resulted in the first monographic publication of the collective’s work.

- Gold Standards: Amanda Williams—This exhibition directly addresses segregationist housing practices in Chicago’s South Side, exploring the histories of segregation, gentrification, redlining, and eminent domain. Williams painted and photographed eight homes in Englewood that were slated for demolition. While these houses are assessed as worthless by the market, the bricks from the demolition are sold at a premium as “Old Chicago Bricks,” trendy material used in new construction projects around the country. Alongside the photographs are bricks leafed with imitation gold and placed on a pallet. This was the first show organized by Assistant Curator Grace Deveney, a former fellow at the MCA.

MCA Chicago’s most profound revision to the canon of American painting occurred in the 2016 exhibition Kerry James Marshall: Mastry, which was co-organized in partnership with the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Contemporary Art LA. The retrospective followed a solo exhibition of his work, One True Thing: Meditations on Black Aesthetics, which MCA Chicago curated in 2004. Grynsztejn described the retrospective as “hugely significant. Not just here but the lines around the corner at Met Breuer and lines at MOCA LA were indicative that he was the artist we needed to see at that moment. It was the fifth highest attended exhibition in our history. Every day the galleries were full, every day someone was crying in the gallery, every day Kerry showed up he was thanked for putting ‘people like me’ on the walls. It was a really powerful moment, it unlocked a lot of pain and anguish and a lot of pride.”

As the exhibitions have diversified, so has the museum’s board. The last four additions to the board have been people of color. Grynsztejn understands that demand is high to diversify boards across the field. She says the museum needs to ask itself, “Why should they say yes to you? You have to show that this is not gloss. That you’re serious. You have to have proof that your institution programmatically is dedicated to diversity and inclusion and has a particular vested interest in that person’s demographic.” As Grynsztejn sees it, the program has to come first, noting that “the Kerry James Marshall show was a huge factor in attracting the last four trustees.” While diversifying collections and exhibitions is important for preserving and fostering the visual cultural heritage of a variety of communities, it can also impact diversity and inclusion efforts among the museum’s staff and board.

Conclusion

MCA Chicago has taken a number of important steps towards diversifying staff, especially curatorial staff, as well as the museum’s board. In addition to increasing representational diversity among museum staff, it has experimented with new ways to realize the values of access, inclusion, and equity in the museum by establishing a committee which pairs board members with staff to develop creative approaches to realizing these values. It has shifted its exhibition projects and acquisitions to reflect the work of artists from historically underrepresented communities; as Beckwith explained, instead of focusing primarily on market-driven assessments of value, MCA Chicago’s curatorial department works to explore “multiple modernisms,” in order to better understand, “what objects tell us about cultural narratives.”

With the museum’s recent remodeling, new spaces have been designed with the intention of increasing access to the public and allowing for new forms of engagement with the museum. As Lydia Ross, who manages school programs, put it, these new spaces serve as a physical manifestation of how the museum has long worked to serve the community. Now she and her colleagues are working toward “internal capacity building to make authentic community partners” with whom to share and activate this space.

While the museum’s new design intends to foster equity among stakeholders, particularly underserved communities in Chicago, many feel that the museum has only recently begun to realize these goals. Chicago’s high degree of segregation and severe class disparities act as a barrier. As director of visitor services Pat Fraser noted, “the museum is in one of the wealthiest zip codes in the city, it’s surrounded by expensive shopping and food.” Fraser is among a number of MCA Chicago staff contemplating how to overcome geographic distance from underserved communities in a segregated city. As Angelique Power says, “MCA Chicago is doing interesting diversity work. They’ve diversified programs, curatorial staff, and board. This puts them head and shoulders above other museums. In this sense, they’ve gotten to the starting point.” However, she added, improving equity in the museum is about disrupting power. MCA Chicago is poised to be a transformational resource where Chicago’s disparate communities can come together. Building trust and a presence in those communities is an ongoing process, and one that MCA Chicago is committed to pursue.

Appendix

Case Studies in Inclusion, Diversity, and Equity among AAMD Member Art Museums

Three years ago, Ithaka S+R, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD), and the Alliance of American Museums (AAM) set out to quantify with demographic data an issue that has been an increasing concern within and beyond the arts community: the lack of representative diversity in professional museum roles. Our analysis found there were structural barriers to entry in these positions for people of color. After collecting demographic data from 77 percent of AAMD member museums, we published a report sharing the aggregate findings with the public. In her foreword to the report, Mariët Westermann, executive vice president for programs and research at the Mellon Foundation, noted, “Non-Hispanic white staff continue to dominate the job categories most closely associated with the intellectual and educational mission of museums, including those of curators, conservators, educators, and leadership.”[27] While museum staff overall were 71 percent white non-Hispanic, we found that many staff of color were employed in security and facilities positions across the sector. In contrast, 84 percent of the intellectual leadership positions were held by white non-Hispanic staff. Westermann observed that “these proportions do not come close to representing the diversity of the American population.”

The survey provided a baseline of data from which change can be measured over time. It has also provoked further investigation into the challenges of demographic representation in this sector. Many institutional leaders are growing increasingly aware of demographic trends showing that in roughly a quarter century, white non-Hispanics will no longer be the majority in the United States, whereas ten years ago the white non-Hispanic population was double that of people of color.[28] This rapid growth indicates that institutions will need to be intentional and strategic in order to be inclusive.

To aid these efforts we set out to understand the following: What practices are effective in making the American art museum more inclusive? By what measures? How have museums been successful in diversifying their professional staff? What do leaders on issues of social justice, equity, and inclusion in the art museum have to share with their peers?

Using the data from the 2015 survey, we identified 20 museums where underrepresented racial/ethnic minorities have a relatively substantial presence in the following positions: educators, curators, conservators, and museum leadership. We then gauged the interest of these 20 museums in participating, also asking a few questions about their history with diversity. In shaping the final list of participants, we also sought to ensure some amount of breadth in terms of location, museum size, and museum type. Our final group includes the following museums:

- The Andy Warhol Museum (Pittsburgh)

- Brooklyn Museum

- Contemporary Arts Museum Houston

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago

- Spelman College Museum (Atlanta)

- Studio Museum in Harlem.[29]

We then conducted site visits to the various museums, interviewing between ten and fifteen staff members across departments and levels of seniority, including the director. In some cases, we also interviewed board members, artists, and external partners. We observed meetings, attended public events, and conducted outside research.

In the case studies that follow, we have endeavored to maintain an inclusive approach when reporting findings. For this reason, we sought the perspectives of individual employees across various levels of seniority in the museum. When relevant we have addressed issues of geography, history, and architecture to elucidate the museum’s role and context in its environment. In this way we show the museum as a collection of people—staff, artists, donors, public. This research framework addresses the institution as a series of relationships between these various constituents.

We hope that by providing insight into the operations, strategies, and climates of these museums, the case studies will help leaders in the field to approach inclusion, diversity, and equity issues with a new perspective.

Endnotes

[1] Don DeBat and Gary S. Meyers, “Manhattan Transfer–Streeterville and the Gold Coast: Second Plushest Neighborhood in U.S. Has It All,” Chicago Sun-Times, January 13, 1989.

[2] Hedy Weiss, “MCA’s 50th Anniversary Celebrates the Now and the Next,” Chicago Sun-Times, August 16, 2017, https://chicago.suntimes.com/entertainment/mcas-50th-anniversary-celebrates-the-now-and-the-next/.

[3] Clay Risen, A Nation on Fire: America in the Wake of the King Assassination (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2009).

[4] Jan van der Marck, Violence in Recent American Art (Chicago: Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, 1968).

[5] Arnold R. Hirsch, Making the Second Ghetto: Race and Housing in Chicago 1940-1960 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

[6] Beryl Satter, Family Properties: Race, Real Estate, and the Exploitation of Black Urban America (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2009).

[7] Nate Silver, “The Most Diverse Cities Are Often The Most Segregated,” FiveThirtyEight, September 28, 2017, https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/the-most-diverse-cities-are-often-the-most-segregated/.

[8]Americans for the Arts, “The Economic Impact of Nonprofit Arts and Cultural Organizations and Their Audiences in the City of Chicago , IL,” in Arts and Economic Prosperity 5, 2017, accessed November 30, 2017, http://www.artsalliance.org/sites/default/files/IL_CityOfChicago_AEP5_CustomizedReport.pdf.

[9] Edward L. Glaeser, Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier (NY, NY: Penguin Books, 2012).

[10] Jonathan Grabinsky and Richard V. Reeves, “The Most American City: Chicago, Race, and Inequality,” Brookings Social Mobility Memos (blog), December 21, 2015, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/social-mobility-memos/2015/12/21/the-most-american-city-chicago-race-and-inequality/.

[11] City of Chicago, “Cultural Affairs and Special Events,” Chicago Cultural Plan (PDF), October 2012, https://www.cityofchicago.org/city/en/depts/dca/supp_info/cultural_plan3.html.

[12] For more on context of the 2015 Art Museum Demographic Survey and this project, see the appendix.

[13] Steven R. Strahler, “Minority Women Resign from Museum Board,” Crain’s Chicago Business, January 29, 2000, http://www.chicagobusiness.com/article/20000129/ISSUE01/100013717/minority-women-resign-from-museum-board.

[14] Alexandre Frenette, Amber D. Dumford, Angie L. Miller, and Steven J. Tepper, The Internship Divide: The Promise and Challenges of Internships in the Arts (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University and Arizona State University, Strategic National Arts Alumni Project, 2015), https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED574458.pdf.

[15] Daniel Indiviglio, “Chart of the Day: Student Loans Have Grown 511% Since 1999,” The Atlantic, August 18, 2011, https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2011/08/chart-of-the-day-student-loans-have-grown-511-since-1999/243821/.

[16] This includes over 15 “checkpoints” that must be met in addition to all of the requirements for A and AA conformance. The exact number is determined based on the website’s content. Some of these requirements, which Coyote addresses, involve providing text descriptions of images. For more see: “Understanding Techniques for WCAG Success Criteria,” Understanding WCAG 2.0, accessed November 15, 2017, https://www.w3.org/TR/UNDERSTANDING-WCAG20/understanding-techniques.html.

[17] Sina Bahram, “Inclusive Design as a Way of Life,” MCA Stories, September, 2017, https://stories.mcachicago.org/speaker/sina-bahram/.

[18] Chris Jones, “This ‘Beauty and the Beast’ is About Sex and Disabilities, for Adults Only,” Chicago Tribune, November 23, 2016, http://www.chicagotribune.com/entertainment/theater/ct-beauty-beast-mca-jones-1125-20161122-column.html.

[19] “Bodies of Work: Using Art to Illuminate the Disability Experience,” College of Applied Health Science, University of Illinois Chicago, accessed February 20, 2018, http://ahs.uic.edu/disability-human-development/community-partners/bodies-of-work/.

[20] Ray Oldenburg, The Great Good Place: Café, Coffee Shops, Community Centers, Beauty Parlors, General Stores, Bars, Hangouts, and How They Get You Through the Day (St. Paul, MN: Paragon House Publishers, 1989).

[21] “BMO Harris Bank Chicago Works, Faheem Majeed,” MCA – Exhibitions, accessed December 22, 2017, https://mcachicago.org/Exhibitions/2015/Faheem-Majeed.

[22] “Multiple Visit Program,” MCA, accessed February 20, 2018, https://mcachicago.org/Learn/Teachers/Multiple-Visit-Program.

[23] Billy McGuiness, Director of Creative Strategies at Sky Art, is currently engaged in a performance piece at MCA, suggesting groundwork for possible further collaboration.

[24] In 2017, the MCA developed a new position, the Partnerships and Engagement Program Liaison, whose mandate is to forge long-term relationships with organizations and communities across the city.

[25] Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago Members’ Magazine, Fall 2016, https://assets-production.mcachicago.org/media/attachments/W1siZiIsIjIwMTcvMTAvMjQvMDkvMDQvNjVkYTYyMjQtYThjYy00NmUwLTk4NmQtY2YwZDcxOGZhZmQ2Il1d/Fall%202016?sha=0a4548b0e8172c0a.

[26] The museum recently acquired works by artists in the show such as Nick Cave and Terry Adkins.

[27] Roger Schonfeld, Mariët Westermann, and Liam Sweeney, “Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey,” Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, July 29, 2015, https://mellon.org/media/filer_public/ba/99/ba99e53a-48d5-4038-80e1-66f9ba1c020e/awmf_museum_diversity_report_aamd_7-28-15.pdf.

[28] William H. Frey, “A Pivotal Period for Race in America,” In Diversity Explosion: How New Racial Demographics Are Remaking America (Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2015): 1–20, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7864/j.ctt6wpc40.4.

[29] We focused on people of color for measuring diversity for two reasons: (1) In the 2015 art museum demographic study, we received substantive data for the race/ethnicity variable, unlike other measures such as LGBTQ+ and disability status, which are not typically captured by human resources, and (2) in the study we found ethnic and racial identification to be the variable for which the degree of homogeneity was related to the “intellectual leadership” aspect of the position (i.e., curator, conservator, educator, director). We are alert to issues of accessibility in this project, and although it was not foregrounded in our original project plan we hope to address these questions in more depth in future projects.

Attribution/NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of the license, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.