Organizing the Work of the Art Museum

Foreword

The career trajectory of art museum directors typically gives them deep exposure to, at most, a handful of institutional settings. While museum directors connect through leadership meetings such as those we host at the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD), and thereby learn from one another, few have the opportunity to assemble a system-wide perspective on how changes in strategy might, or perhaps should, affect their institutional leadership.

Given the strategic transformations that many art museums are undertaking or considering, we recently asked Ithaka S+R to analyze the ways that strategic change and organizational change connect with one another. The result is this report on strategic direction and organizational structure, based on a study of the organizational charts of roughly one third of AAMD member museums and interviews with roughly 20 of our member directors.

The study’s authors find that as many art museums work to deepen their audience engagement and reach new audiences, they are tending to adjust their organizational structure accordingly. Their findings speak to the distinctions between larger and smaller museums, as well as differing museum types. This study provides art museum leaders with a clear set of findings for their consideration. We look forward to continuing to develop, with our partners, actionable findings to help museum directors navigate change and lead their institutions into a vibrant future.

Christine Anagnos, Executive Director, AAMD

Introduction

As public institutions that house objects of art-historical interest, art museums occupy an unusual position as educational, scholarly, and civic institutions, with one foot in the academy and one foot in their communities. In the 21st century, there is an increasing focus among museums to expand the communities that they engage and serve, the buildings they serve them from, and the staff they serve them with.[1] How are these goals reflected in the structure of these institutions? In order to better understand how art museums organize themselves, and in what way the structure of the museum relates to the strategic direction that the museum hopes to realize, Ithaka S+R and the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) have partnered to analyze the organizational structures of its membership.

Key Findings

Through our analysis of organizational charts from over 80 AAMD members and interviews with 17 museum directors, we draw the following high-level conclusions about the strategy and organizational structure of art museums:

- As art museums pursue strategies to become more engaged with visitors and to discover new audiences, there are clear and direct implications on the institutions’ organizational structure and strategic planning processes

- Museums that have recently undergone expansions or renovations subsequently shifted their strategic focus to audience engagement

- Choices in how senior leadership teams are structured dramatically affect how directors spend their time

- In cases where museums have identified clear strategic priorities, organizational structures can be crafted to reach these goals

Looking at a broad variety of museum types and contexts, our analysis provides insight on the shifting priorities of the sector as a whole, and how these changes manifest within individual organizations.

Methods

In the summer of 2018, AAMD asked member museum directors to share their organizational charts for this project. Eighty-six charts were collected, representing about 39 percent of the membership. In the first phase, Ithaka S+R analyzed these documents and developed some key findings, studying commonalities and differences across the sample. From this process, several key topics emerged:

- How do education and curatorial departments relate to each other?

- How do curatorial departments and collection departments relate to each other?

- How do marketing/communications and development departments relate to one another?

- Under what circumstances do directors consolidate operations under a chief operating officer or deputy director?

We then identified 17 museums, which were in some cases representative of and in other cases outliers from the norms we observed. These museums were selected in coordination with AAMD with the intention of collecting perspectives from different types of institutions—college/university, encyclopedic, and contemporary museums as well as museums with budgets ranging from under $5 million to over $100 million. More than three quarters of the museums accepted our invitation to participate in this phase of the study. We developed an interview guide that focused thematically on broad issues of strategy and structure as well as specific functional and departmental issues. We conducted semi-structured interviews with the directors of those 17 museums.

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

- The Frick Collection

- Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington

- Kalamazoo Institute of Arts

- Minneapolis Institute of Art

- Museum of Contemporary Art, Denver

- Museum of Modern Art

- Nelson Atkins Museum of Art

- Perez Art Museum Miami

- Princeton University Art Museum

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

- UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive

- Utah Museum of Fine Arts

- Whitney Museum of American Art

- Williams College Museum of Art

With this sample, we were able to gather qualitative data from the directors of museums that varied by a number of characteristics, including budget, staff size, institution type, geography, and age of the institution.[2] It was not within the scope of this project to analyze historical trends in organizational structure, but we made note of significant historical restructurings as they arose. The findings below are a synthesis of our analysis of both the organizational chart archive and the subsequent interviews. In some cases, findings have been generalized in order to preserve the anonymity of the participants.

Strategic Directions

We did not set out in this project to conduct a comprehensive survey of all art museums, yet our findings suggest the significance of two dominant priorities of museum leaders: expanding or renovating physical space and building relationships with new audiences. These priorities have a relationship with one another.

Twelve of the 17 interviewees described how their museums are newly focusing on more inclusive community engagement. In most cases, this followed a recent building expansion project, which had previously occupied much of the leadership’s attention. Indeed, among those museums not explicitly prioritizing issues of audience engagement, several were in the midst of major building projects themselves, and some of these leaders indicated that priorities would shift towards audience engagement once their expansion projects had concluded. This is the trajectory observed in the case study, “At Fifty, Remodeling for Equity: MCA Chicago,” which details a single case of an institution designing a renovation around the values of inclusion, access, and equity.[3]

We discuss these two dominant priorities at greater length below. A smaller share of leaders raised additional priorities, including technology and staff diversity. We heard very little about collection development, except occasionally in relation to efforts towards diversifying the museum’s collection.

Building Expansion and Renovation

While several of the participants in this study had no plans to expand or renovate, a large enough portion had either recently expanded or were currently planning an expansion or renovation. Most of the expansion projects undertaken by the interviewees over the last five years occurred at encyclopedic museums with budgets over $20 million. The growth of these large museums tracks with the broader field. As the economy has recovered from the 2008 recession, the museum field has grown as well. For instance, recent data show that between 2014 and 2015, the arts and culture sector grew at a rate of five percent after adjusting for inflation.[4] In response to the economic recovery, one director noted that there had been an increase in individual giving from those who had accrued wealth during this time.

Participating museum directors shared a variety of different approaches in terms of their levels of involvement, both with the fundraising and with other aspects of expansion projects. In particular, several directors shared that someone from the museum, if not themselves, needs to take a very active role in the design and construction phases of an expansion project. This includes, in many cases, dedicated on-site supervision during the construction phase. This staff member could be a project manager or deputy director, dedicated exclusively or principally to the project, sometimes working with a small team. In these instances, new construction can have at least a temporary impact on organizational structure. Often an expansion requires an increase in permanent staff. This may include staff for security, visitor services, education, facilities, and more.

Visitor Centered Museum

In 2015, at the ceremony opening Renzo Piano’s new location for the Whitney Museum of American Art, Michelle Obama spoke about the imperative for cultural organizations to find ways to connect with populations who have been historically excluded and ignored by elite art museums. In it, she notes, “There are so many kids in this country who look at places like museums and concert halls and other cultural centers and they think to themselves, ‘well that’s not a place for me. For someone who looks like me, for someone who comes from my neighborhood.’” She challenged the Whitney to overcome these obstacles and become welcoming to and engaged with these populations.[5] Adam Weinberg describes Michelle Obama’s speech at the opening as a stand-in for the museum’s strategic plan. This perspective was echoed by many directors as a primary concern of the museum. For instance, Crystal Bridges’ mission to “welcome all” to celebrate American art is simultaneously obvious and radical.

For museums to build trust in communities, active and sustained measures must be taken to realize this goal, each of which require substantial investment of human and financial resources. Ithaka S+R has previously written at length about a variety of important measures in a 2018 series of case studies about diversity, inclusion, and community engagement.[6] In the present project, interviews revealed the many organizational choices that art museums are making to reorganize their museums towards a more visitor-centered strategy. Museums have grown their public program departments or elevated education departments within the structure of their organizations.

Organizational Choices

Many museums have established structures that reflect, and ideally enable, their strategic direction. Given the fairly common set of strategic directions that directors described, it is no surprise that there are a number of common elements across museums in how their structures are evolving. Before addressing this evolution in subsequent sections, we first share some of the design choices and dilemmas in how museums are structured and how that structure is represented.

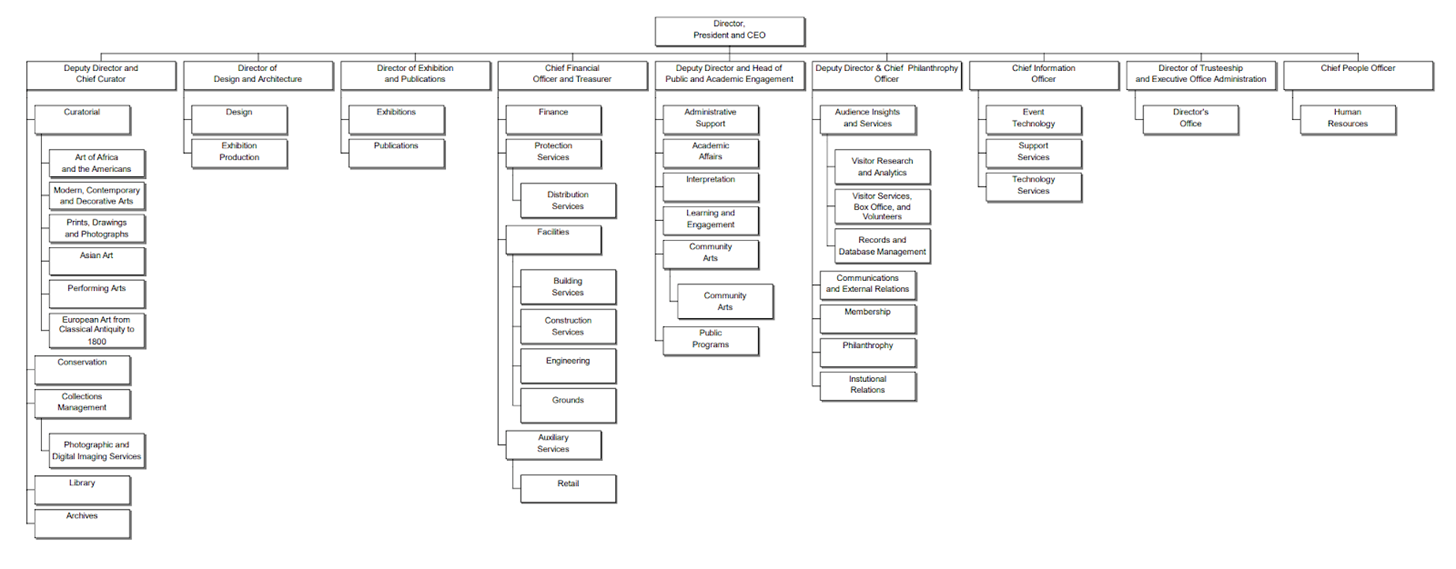

In the typical museum, there is a hierarchical organizational model, featuring a group of roughly six to eight departments, generally including curatorial, education, collection management, marketing, development, security, and facilities. A fairly typical organizational chart for a large encyclopedic museum is presented below.

Figure 1: Traditional Organizational Chart Model

This chart shows that the museum is mainly organized under three deputy directors and a chief financial officer. The deputy director/chief curator has responsibility over the discipline-specific curatorial departments, the conservation department, collections management (including photographic and digital imaging services), and the library and archive. The CFO and treasurer oversees finance, human resources, protection services, facilities, and the store. The deputy director and chief philanthropy officer oversees audience insights and services (which includes visitor services, visitor research and analytics, and records and database management), communications and external relations, membership, philanthropy, and institutional relations.

Smaller department heads include the director of trusteeship and executive office administration, which handles the director’s office and manages board relations, as well as the director of digital innovation and technology services, director of design and architecture, and director of exhibition and publications.

This reflects the way a large encyclopedic museum without a chief operating officer might look, with most of the departmental responsibilities distributed among a few deputy directors or C-suite positions. But at the same time, a review of dozens of organizational charts made plainly obvious the fact that museums are organizationally anything but uniform. As one director put it, they represent an entanglement of personalities, history, and logic.

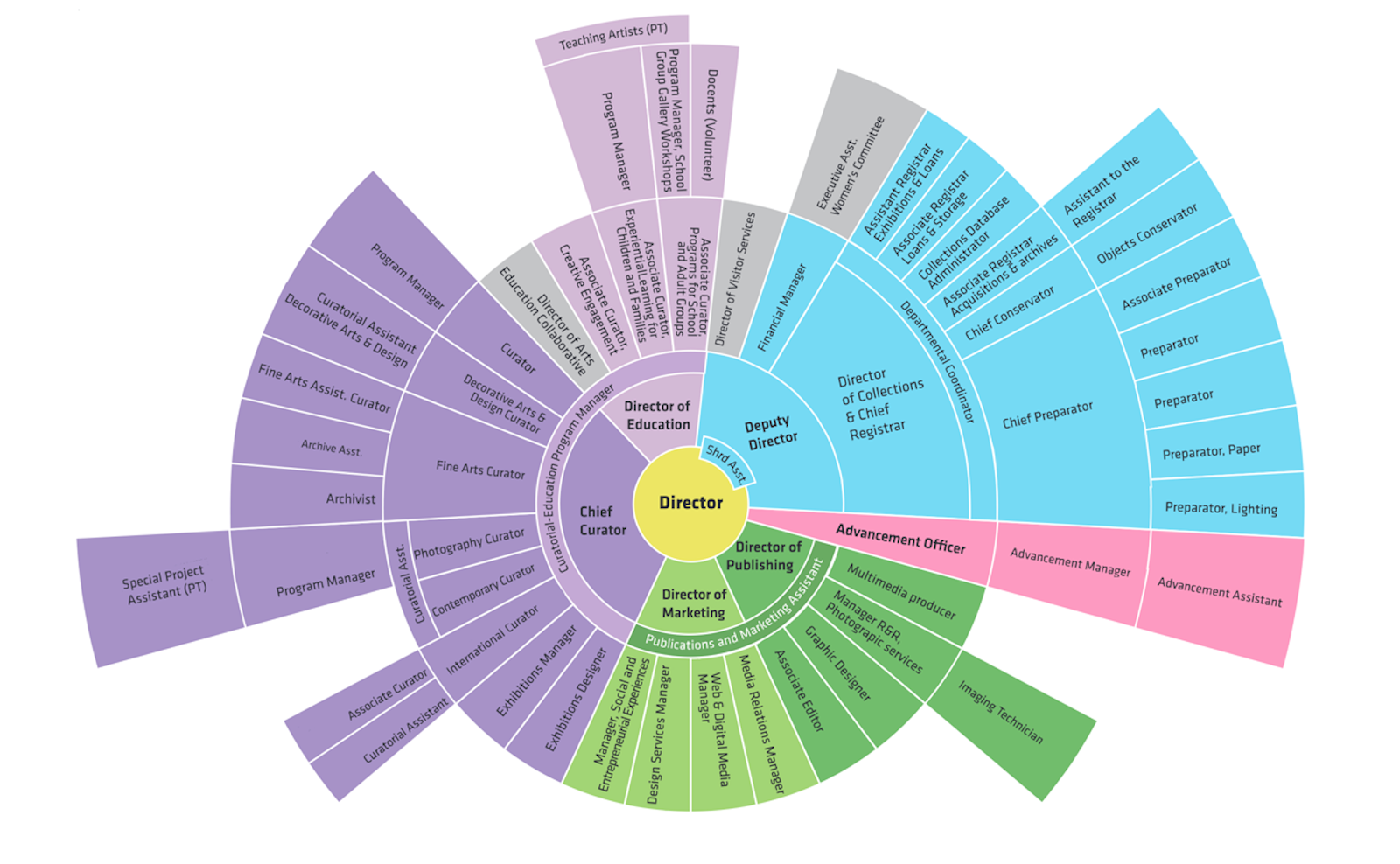

As these characteristics interact to define the structure of the museum, they occasionally produce examples of a non-traditional organizational chart, such as the one illustrated below. Sometimes, this effort to create a more horizontal organizational chart may reflect a certain kind of strategic imperative. For instance, notice that the chart below uses color to indicate alignment between departments. Dark and light green represent marketing and publishing, and these departments share a publications and marketing assistant. Whereas light and dark purple show a connection between curatorial and education departments, which share a position with the title: “curatorial-education program manager.” This chart indicates a structural decision to emphasize alignment between these departments.

Figure 2: Organizational Chart featuring Horizontal reporting relationships

This chart shows that a deputy director is tasked with managing visitor services, the financial work of the museum, as well as collections management and registrarial work. Much of the remaining personnel is divided between the chief curator and the director of education, director of marketing, and director of publishing. An advancement officer also manages a small team.

Whether or not it is executed in practice, this chart attempts to visually reflect a style of work that we heard is increasingly common within the museum: horizontal, team based work. In fact, some directors with more traditional organizational charts indicated to us that the reporting relationships visible in the chart do not accurately reflect the working relationships in the organization because it is a challenge to visualize these horizontal approaches to work.

The Role of the Director

In some cases, particularly in smaller institutions, a director might identify primarily as a chief curator, considering fundraising and/or personnel management to be important but secondary to the focus on art. In these cases, individuals spoke especially eloquently about their curatorial partnerships and vision and how these connect to the communities they serve.

It was most frequently the case that the directors interviewed were deeply engaged in fundraising for the museum, reporting that they spend roughly 60 to 70 percent of their time courting donors and raising money for the institution (though a minority of directors had deliberately found ways to reduce this amount of time). At the largest museums, which maintain large-scale development operations, the director may focus on only the largest prospects and stewardship of only the most important donors, so that they can continue to maintain at least some connection with the intellectual leadership roles as well. One director told us that in a current campaign to raise over $200 million for a new building, donors to the museum have historically received an in person request for a gift from the director for sums as low as $10,000, but “there aren’t enough lunches in the year.” They are now creating a tiered development structure to try to break that expectation.

Directors rarely see themselves principally as people managers, yet some spend a meaningful portion of their time on management. The amount of time spent managing personnel in the museum was typically dependent on the way senior leadership teams were structured. This often was determined by the director’s personal management preferences, as well as the resources available to them.

At one museum, the director described a strong partnership with a deputy director who was able to act as a proxy for the director in most situations. This created a great deal of flexibility, allowing the director to focus more on external matters, but this situation was very circumstantial in that it was driven by the personality and deep institutional knowledge and relationships held by the deputy director.

Conversely, certain directors had a high number of direct reports. In some cases, this was due to a disinclination to devote scarce resources towards additional leadership roles. In other cases, it was due to some combination of the symbolic and real value that their oversight added to the museum. In one especially striking case, the heads of curatorial departments reported directly to the director, creating an organizational chart with well over a dozen direct reports, even though it was not clear that the director actually exercised any meaningful personnel management over these individuals.

Organizing Senior Leadership

Roughly half of the museums that submitted organizational charts had a chief operating officer who managed approximately half of the museum’s staff. Typically, the COO takes responsibility for many if not all of the “business” functions of the organization, allowing the director to focus more squarely on the leadership of the museum’s intellectual work. To illustrate how these COO models are operationalized, we provide an overview of the departmental responsibilities of the COO at the five museums represented by interviewees that utilized this model.

Table 1: Museums with Chief Operating Officers: Characteristics and Departmental Reports

| Budget Range | Museum Type | Departments in Operations |

|---|---|---|

| $20-100 million | Encyclopedic | Museum store, event planning, volunteer services, advancement fundraisers, food services, guest services and security, earned income and guest services, human resources, finance |

| $20-100 million | Encyclopedic | Communications, strategy, creative services, digital media, media relations, development, guest services |

| $20-100 million | Encyclopedic | Exhibitions and collection management, communications, facilities, finance, legal, publications, strategy, trustee office, visitor experience |

| $20-100 million | Encyclopedic | Accounting, human resources, facilities, security, business development, retail |

| Over $100 million | Contemporary | Finance, investments, facilities and public safety, international council, internal audit, human resources, information technology, retail |

Sometimes multiple deputy directors reported to the director, whereas in other cases the museum had a single deputy director who clearly acted as the second most senior employee. The structure of the director’s senior leadership team has an impact on the time the director spends on managing staff versus working on fundraising and the programmatic functions of the museum.

One director observed that a true COO often has to grow out of finance because that is such a specific and technical skill, which is hard to learn in an unofficial capacity and is essential to that role. In this philosophy, a good COO needs to be able to both manage numbers and manage people. The director is then able to devote more time to the museum’s program.

Another museum opted for two deputy directors, one for operations and one for programs. This frees up the director to be more proactive about fundraising. At this museum, the management group includes not only those two deputy directors but also most of their direct reports, including the heads of marketing and PR, development, and collections as well as the chief curator and director of education and engagement. With this model, the director spends time with a senior leadership group, but the majority of management responsibilities are handled by the two deputy directors.

One director noted that while they do not have a deputy director, they find it useful to have a chief of staff. As they describe it, the directors of various departments each are advocating for their own teams. It is important to have someone in a senior role whose primary allegiance is to the director’s agenda, rather than their own department. Another director insisted that the museum had cultivated a culture of prioritizing the work of the museum over the reputation or ambition of any individual member. This is of course an ideal climate, but can be difficult to develop when staff or departments prioritize their own advancement relative to other parts of the organization. In this particular museum, there was an emphasis on developing cross-departmental teams, which may help facilitate such a culture.

Another important factor is that organizations are comprised of individuals. The depth of institutional knowledge that comes from many years in the same museum may lead a director to elevate a department head, who would otherwise not be a direct report, to a senior leadership group. An ambitious department head might make a persuasive case for consolidating another department under their purview. Directors navigate these idiosyncrasies while bringing their own logic to the structure of the museum.

As part of an effort to deepen their commitments to equity in the museum, one museum has restructured in order to bring museum services, which is responsible for management of facilities and security operations, into the senior leadership group. The department, which at most museums in the US is among the most diverse, is also the lowest paid in the museum field, according to the AAMD salary survey, and often does not have a “seat at the table.”[7] This museum, however, recognized that certain staff had been working in the museum for decades, and wanted to bring the depth of institutional knowledge in those roles into a greater leadership position.

Departmental Structures

The organizational charts revealed certain noteworthy relationships between departments, or differences in their relationship to the director. The interviews provided greater clarity as to the nature of these differences. The following sections explore these findings.

Marketing and Development

Roughly 15 percent of the organizational charts showed museums pairing their marketing and development functions in the same department. In some cases, the department was called development or advancement, with marketing nested within it, while in others the department was called external affairs, with development and marketing both reporting to the head of external affairs. In interviews, it appeared that this arrangement had been more common in previous years. Several directors inherited this configuration when they joined the institution, and have since separated the two departments.

The marketing department acts as the voice of the museum, shaping its public identity, and signaling who the museum sees as its audience. Directors who had separated marketing from development did so for two reasons. Functionally, they wanted the marketing department to operate more explicitly as an internal service for the various departments of the museum, including publications, education, public programs, curatorial, etc. Strategically, they wanted the voice of the museum to speak more explicitly to the broadest possible audience, rather than focusing on the museum’s donors and membership program. By decoupling marketing from development, marketing departments were encouraged to help multiple departments in the museum speak to a variety of audiences.

Nonetheless, directors were clear that marketing still must work closely with development in order to maintain strong communications with current and future donors, and develop strong materials for membership events. It is therefore essential to consider capacity, staffing, and resources for the marketing department if its role in the organization is expanding its constituency.

Education and Curatorial Departments

Central to emerging discourse concerning the museum’s emphasis on visitors is a shift in the dynamics between curatorial and education departments. Traditionally, museum directors have come from curatorial backgrounds, and though that trend is changing, roughly three quarters of AAMD member museums are headed by former curators.

Directors were consistent in their agreement that education departments needed to play a stronger role in the museum than has previously been the case. Indeed, these values were often visible in the organizational charts, where education departments in many cases were visibly empowered with the head of the department reporting to the director, and often with public programming housed in the department.

One director expressed that education departments had formerly been considered inferior to curatorial departments as a result of problematic gender stereotypes, describing an attitude towards museum educators as the women who will “wipe the noses” of the children visiting the museum. Recognizing the widely accepted need to re-center the museum on its visitors, this director was surprised that the attitudes of young curators were not tracking with the broader changes in the field: “I find that the young curators I interview, recent PhDs, are often worse [at collaboration] than the curators who have been here for a while, often more resistant to community engagement.” As strategic plans shifts towards stronger forms of community engagement, organizational structure and institutional culture are challenged by deeply held perspectives on the value of these roles in the museum.

Generally, directors were split in their analysis of relations between curatorial and education departments. Some found that great strides had been made and productive collaborations were underway. As one director of a university museum described,

The dynamics between curators and educators is one of the things I care most about in the museum world. In that respect, this museum is really ahead of the curve. We have a curatorial engagement team that fosters engagement between these departments, it meets every other week. We have regular brainstorms, workshop ideas for exhibitions and programs. That’s a large group. It doesn’t set the program, but it brainstorms ideas before they are set in stone by senior leadership. I think often the relationship between curatorial staff and education is more fraught, but I think it’s probably one of the strongest working relationships here.

Another director described how important it is in the hiring process to gauge this type of openness between curators and educators, while expressing some frustration that the curators applying to the museum sometimes do not share these values: “My favorite educators think a lot about art, my favorite curators think a lot about audiences. I’m amazed by how resistant curators can be about these issues. We have a lot of work to do train people up to this. You can’t be a curator who is thinking only about art and objects, without thinking about audiences.”

Other directors shared this frustration, expressing that collaboration between these departments was not where they would like it to be. Typically this was a result of curatorial departments perceiving education staff as playing a “support role.”

Among the 17 interviewees in this project, 12 directly manage the head of the education department. Eleven of the education departments had more than three direct reports from sub-departments. The titles of education department heads included associate director of education, director of education, curator of education, and deputy director of education.

In about half of the cases, there was an addition to the title, such as public practice, interpretation, public and academic engagement, youth and public programs, research in learning, and public programs.

Directors see these roles as essential for audience development. As books such as Room to Rise have shown, educational programs in the museum can have a lasting impact on an individual’s relationship to the entire field. As directors shift their focus to deepening audience engagement, these roles are being rethought, and often rising into senior leadership positions.

Wall Labels

The dynamics between curators and educators came up frequently in discussions about the strategic directions of museums. But it can be hard to tell the degree to which these perceptions are a reflection of a familiar narrative, rather than observations grounded in experience. When asked for concrete examples of this conflict, directors often identified the front line manifesting in the text of wall labels in the museum’s galleries. One director explained that labels are deeply political in their museum: “We struggle with the decision about where this ultimate authority rests. It’s important because it determines the kind of experience you want the public to have. You can shape what they’re seeing through that label.”

Another museum director used a recent renovation as an opportunity to build collaboration between education and curatorial departments. The two departments rewrote 500 wall labels together for the reinstallation. The director noted, “It seems for the most part to be a productive collaboration, but there has been some mild tension around ‘dumbing down.’”

As the director of a large encyclopedic museum described, “The critique that comes is that you are watering down the content, or ‘dumb it down.’ But I don’t want to ‘dumb it up’ either. That is what I call using PhD jargon on labels so that no one can read it. We begin with information from curators with the highest level of scholarship, but we are going to make it relevant to the public.”

In order to build consensus around this idea, this director constructed an experiment with the museum’s educators and curators:

We once had a very simple exercise where the curators’ labels were rewritten by education and curatorial, and then tested in the galleries with the help of an internal researcher. The researcher asked visitors at random to read the different labels, with the curator and educator present. The only thing the curator needed to see was where the reader stumbled. It was eye opening for the curator that people stumbled, or stop reading or lost interest early in the label.

Building collaboration between curators and educators means developing consensus about the intention of the exhibition—particularly, determining whether it is for the curator’s peers, or the broader public.

Collections Management and Registrar

One of the museum roles in which institutional history played a substantial role was that of collections management/registrar.

In roughly fifty percent of the organizational charts, the head of collections reported to the director and was part of the senior leadership team, typically serving alongside as a peer to the chief curator (although in a small number of cases curators were actually housed within the collections department). In most of the other cases, the collections staff reported to the chief curator or equivalent.

Institutional knowledge can dictate the roles that people play, especially when it comes to collections management. For instance, at one of the participating museums, the head of collections has been on staff for roughly 35 years, and protected the collection through a turbulent time at the museum. The director in this case believes that as a result of this deep institutional knowledge it makes sense for the head of collections to have more independence and not report to the head of the curatorial department. Another director pointed out that they liked having the head of collections as a direct report, because if issues arise with the collection they want to hear the news directly.

Part of this difference in perspectives is accounted for by different roles assigned to collections management. In some museums, these are registrarial functions. In other cases, collections management may include conservation, exhibition planning and design, and a number of other functions.

At one of the large encyclopedic museums that participated, curatorial and collections function as separate departments. The director says there is value in having collections management as a direct report alongside collections because it keeps curators accountable when thinking about donors, new media, and to be thoughtful about conservation of objects.[8] However, in another large encyclopedic museum, the director couldn’t imagine overseeing the collections department directly, noting that would be far too in the weeds, and “they weed brilliantly.”

Technology and Collaboration

Many directors discussed that their museum needs to rethink its relationship to technology and is making meaningful investments in this direction. In some cases, this meant reconceptualizing roles in IT departments. One director told us they created a CTO position in order to better court donors for whom such a title/structure would be relatable.

In many museums, technology is becoming a more central component of much of the work outside of IT, including communications/external affairs/marketing, education, publishing, collections management, advancement, and audience engagement. However, as the AAMD salary survey has shown, there are significant pay gaps between many of these departments.[9] While digital learning is on the rise, requiring increasingly sophisticated technical skills from staff in, for instance, certain education departments, salaries are often benchmarked by corollary roles in the private sector. In this way, competition in the private sector that reflects the extreme disparity in the way technologists and educators are compensated can manifest within the museum while at the same time responsibilities and skill sets broaden.

At the same time, many directors recognize that museums have a reputation for being slow to adapt relative to the private sector. To varying degrees, but with consistency, museum directors expressed a desire to create a more “nimble” work environment wherein the museum could be more responsive to the rapidly changing digital landscape, to the broader art world, and to the museum’s local environment.

To a degree, this nimble quality has been pursued through a shift to more team based or horizontal working relationships in the museum, due to an increased emphasis on cross-departmental collaborations and more informal working relationships between staff. However, this is not to say museums in our sample are experimenting with alternatives to management hierarchies as dramatically as can be seen in certain private sector firms. Companies like Zappos, Morning Star, and the computer game company Valve have been high profile examples of companies experimenting in “Holocracy” or self-managing organizations, which have “radically decentralized authority in a formal and systematic way throughout the organization.”[10]

Rather, roughly one-third of the directors we spoke with described working incrementally toward less hierarchical management styles through increased team-based approaches. Unfortunately, mapping these relationships was beyond the scope of our project, but may be a fruitful area for further research.

Conclusion

Since the recession of 2008, art museums have grown in both size and scope. Physical expansions and renovations have been necessary to show more of the museum’s collection, increase programs, and update facilities. Art museums are confronting the challenge of broadening their audiences in order to better serve a rapidly changing public, with increased demands and expectations. A variety of strategies emerge from these efforts, from making the organization more horizontal or vertical to building “dotted lines” between certain departments, which have implications in the way senior leadership teams and departments are organized within the institution.

But determining the structure of the organization involves many variables. The institutional history and reputation of a museum inevitably inflects these decisions. And in many cases intangible features such as the personality of senior staff and board members, and the working relationships between colleagues determines decision making, for better or worse. The director must weigh these considerations with the imperatives dictated by the museum’s strategic plan. In some cases essential but informal collaborations may emerge from this process.

In the end, this project has found substantial opportunities for museum leaders to realign organizational structure in the service of the museum’s most important priorities and overall strategic direction. Of course, a vital prerequisite is in fact to develop a strong sense of priorities and strategy. With these in place, structural choices can, and in many cases should, be made accordingly. For those museums working to broaden their audiences and re-center themselves around their visitors and users, providing the necessary human resources and organizational structure is the vital work of every leader.

Endnotes

- Peggy Levitt, “Museums Must Attract Diverse Visitors or Risk Irrelevance,” The Atlantic, November 09, 2015, https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/11/museums-must-attract-diverse-visitors-or-risk-irrelevance/433347/. ↑

- While these museums were selected to represent the variety of institutions within AAMD, we are aware the majority of directors represented are white and male. This project did not seek to report specifically on institutions with diverse leadership, as we did in the series of diversity case studies, but rather to represent the variety of institutional members. ↑

- Liam Sweeney and Katherine Daniel, “At Fifty, Remodeling for Equity: MCA Chicago,” Ithaka S+R, 7 June 2018, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.307510. ↑

- Office of Research & Analysis National Endowment for the Arts, “Arts Data Profile: The U.S. Arts and Cultural Production Satellite Account (1998‐2015),” March 2018, https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/ACPSA_2015-Brief1Access-v3.pdf. ↑

- Michelle Obama, “Dedication of the Whitney Museum of American Art,” (speech, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City) April 30, 2015. ↑

- Liam Sweeney and Roger Schonfeld, “Interrogating Institutional Practices in Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion: Lessons and Recommendations from Case Studies in Eight Art Museums,” Ithaka S+R, 20 September 2018. https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.309173. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Eight of the 17 participating museums had conservation departments. Only two of the heads of those departments reports to director while eight report to the chief curator. ↑

- “Salary Survey,” Association of Art Museum Directors, July 3, 2017, https://www.aamd.org/our-members/from-the-field/salary-survey. ↑

- Michael Y. Lee and Amy C. Edmondson, “Self-Managing Organizations: Exploring the Limits of Less-Hierarchical Organizing,” Research in Organizational Behavior 37 (2017): 35-58. ↑

Attribution/NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of the license, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.