Do Physical Books Still Spark Joy?

On the Material Reality of Today’s Academic Libraries

Marie Kondo of Tidying Up, the decluttering-as-self help phenomenon, recently met controversy for declaring that she strictly limits the number of books in her home to thirty. She has since clarified that the optimal physical book collection size is a personal metric, however, the underlying controversy echoes an issue that many academic libraries are facing around the role and presence of physical books.

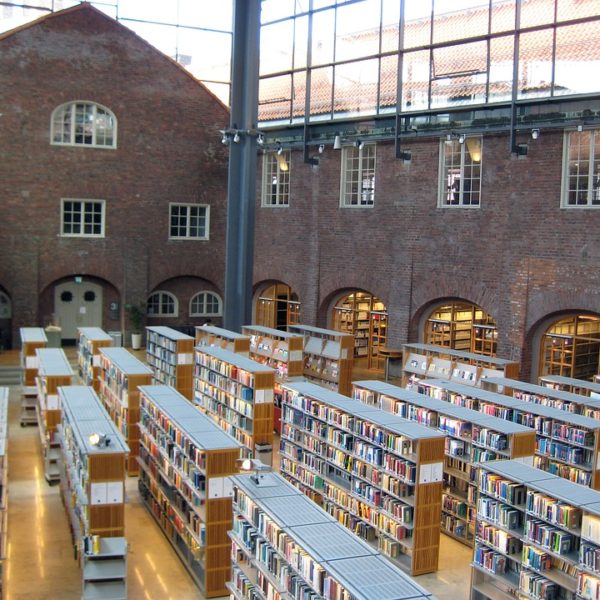

Increased availability of digital content coupled with changing expectations for how space on campus is leveraged have transformed the debate around how books occupy physical library spaces, and by extension, what a physical library space is. Long gone are the days where physical books were so precious that they needed to be chained to desks. Fading before our eyes is also the time where book warehousing was an essential library service with “serendipitous” browsing positioned as a positive bi-product.

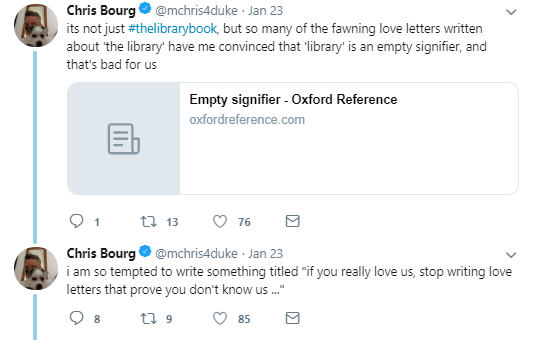

As Chris Bourg recently suggested while critiquing Susan Orlean’s recent missive, The Library Book, or Lorcan Dempsey when reflecting on the aesthetic of libraries celebrated through internet clickbait, to keep books chained (metaphorically) to the brand of the library represents a fundamental misunderstanding of what books AND what libraries are in the 21st century. With the promise of decoupling physical books from the library, and the freed-up library space that comes with it, many are taking opportunities to re-align libraries with what Michael J. Khoo, Lily Rozaklis, Catherine Hall, and Diana Kusunoki aptly term “learner-centred space paradigms,” such as by creating makerspaces and collaboratories. Some libraries, such as UT Austin, are now actively exploring the future of their library spaces, and it can be expected that the outcomes of some of these explorations will be relinquishing space to other entities.

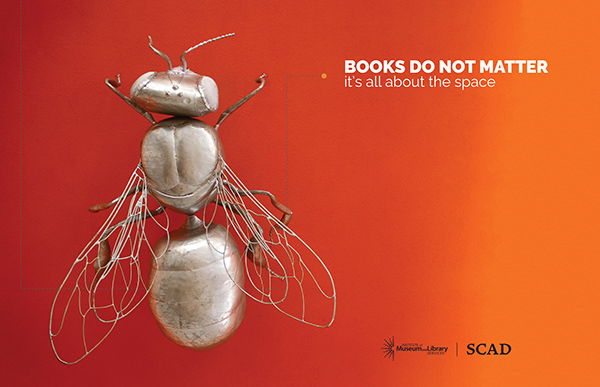

And yet, as Khoo, Rozaklis, Hall and Kusunoki find, “book-centred paradigms” for organizing library spaces continue to resonate with academic library patrons. And as both they and the researchers from the A Day in the Life project also found about student space-use practices, 21st century library visitors continue to find value in ye-olde carrel desk. But consider the findings from Nancy Fried Foster in August 2018 on how Yale student perceptions should inform the renovation of Bass Library alongside the findings on student needs at SCAD’s Jen Library that informed the IMLS-funded Library User Experience Design Toolkit project in 2017. At Yale the conclusion was that “students like to work in a library where they are surrounded by books. They seek out course reserve books from the stacks, but they do not spend much time randomly browsing,” whereas at SCAD it was that “books do not matter, it’s all about the space.”

Could the physical presence of books, by virtue of their symbolic and aesthetic virtues, ability to provide privacy vis a vis shelving, and, perhaps muffle noise, constitute a learner-centred approach to space design? From my vantage point there seem to be some real risks for libraries that go too far with that kind of rationale but also with throwing out all the books and starting from scratch. For those still undecided, may I suggest some A/B testing of whether bookshelves or green walls are more effective for promoting quiet study? In the meantime, I look forward to hearing more from others in academic libraries about how they are navigating these issues.

Comments

"...by virtue of their symbolic and aesthetic virtue..." Really? The fact that survey after survey, including those by Ithaka, show that faculty and students prefer print to e-books for long-form monographs seems to count for nothing as far as the actual value of print books go. As professionals, don't we have an ethical obligation to support faculty and students? If we know that they are more likely to read and comprehend a print books, do we not have an ethical obligation to keep purchasing them? And, God forbid, keep them on shelves in the library where people can actually get at them? I've been an academic librarian for 30 years and I've never understood the rush to ditch print books, as if a library can't have both technology and print books. It seems to have gone hand-in-hand with signing on to crippling e-journal and now e-book packages that have allowed major publishers to grow to the point where they "own" our budgets. Not quite ethical on our part, you might say. (Speaking of ethics, one question I've always had is why academic librarians never talk about professional ethics.) Rather than rushing towards a library space that we think better represents how "with-it" we are, why not think of an ethical obligation to create library spaces that best meet the needs of what we know our faculty and students want. Maybe book centered paradigms resonate with library users because library users (unlike most academic library directors) actually use libraries and even go so far as to read print books. You might want to read Maryanne Wolfe and Naomi Baron, in whatever format you prefer. Sorry for the rant, but really?

Thank-you! As one who prefers print, I appreciate this comment. I for one do not absorb nearly the amount of information I read on a screen as I do in an actual printed text. I abhor the current "It's all online anyway" mindset that is becoming far too prevalent, not only in the academic setting, but in many public libraries as well. No, it is NOT "all online." The tactile experience cannot be replicated onscreen. My Kindle is convenient when I want to read at night in the dark, but it will never replace a real book for the experience.