CIC Consortium for Online Humanities Instruction

Evaluation Report for Second Course Iteration Treatment

-

Table of Contents

- Summary of Findings

- Data Sources

- Limitations of the Study

- Goal 1: Building Capacity

- Goal 2: Enhancing Student Learning

- Goal 3: Increasing Efficiency

- Overall Assessment

- Conclusion

- Appendix A: Consortium Members (2014-2016)

- Appendix B: Instructor Survey

- Appendix C: Student Survey

- Appendix D: Rubric for Peer Assessment

- Appendix E: Interviewee List and Interview Scripts

- Endnotes

- Summary of Findings

- Data Sources

- Limitations of the Study

- Goal 1: Building Capacity

- Goal 2: Enhancing Student Learning

- Goal 3: Increasing Efficiency

- Overall Assessment

- Conclusion

- Appendix A: Consortium Members (2014-2016)

- Appendix B: Instructor Survey

- Appendix C: Student Survey

- Appendix D: Rubric for Peer Assessment

- Appendix E: Interviewee List and Interview Scripts

- Endnotes

The Council of Independent Colleges, a membership organization of more than 700 institutions, aims to support independent colleges and universities and their leaders as they advance institutional excellence and help the public understand private education’s contributions to society. CIC members, historically, have taken considerable pride in their offerings of highly personalized instruction for their students. As online learning began to be discussed in the mainstream media, CIC members considered the implications of this new form of pedagogy for their institutions.

The CIC Consortium for Online Humanities Instructions was formed in 2014, with support from a grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Twenty-one institutions were selected through a competitive selection process for the first consortium.[1] Each institution agreed to develop two online or hybrid courses, offering them in the first year to their own students, and making them available to others in the consortium in the second year. The results of the first year’s work were reported on in September 2015. The CIC Consortium for Online Humanities Instruction (2014-2016) completed its second year with the spring 2016 academic term, during which participating faculty offered their revised first year courses to all students in the Consortium. During the second course iteration, 38 participating faculty offered 37 courses (two faculty members, one at Connecticut College and another at Trinity College, co-taught a course).[2] This report analyzes evidence generated from the planning period and second iteration of CIC Consortium courses, including relevant comparisons between first and second iterations of courses. It includes a summary of findings, with accompanying data visualizations.

The CIC Consortium set out to address three goals:

- To provide an opportunity for CIC member institutions to build their capacity for online humanities instruction and share their successes with other independent liberal arts colleges.

- To explore how online humanities instruction can improve student learning outcomes.

- To determine whether smaller, independent liberal arts institutions can make more effective use of their instructional resources and reduce costs through online humanities instruction.

CIC’s Consortium for Online Humanities Instruction, from the perspective of faculty who taught the courses and from students enrolled in the courses, was a success. The 21 liberal arts colleges participating in the project have taken pride in their personalized instruction for their students. Prior to joining the consortium, many faculty and administrators questioned the appropriateness of online courses in liberal arts institutions that bill themselves as hands-on, high-touch, and customized to student needs. Answering these questions motivated many faculty to participate; they were eager to explore whether online courses could augment and reinvigorate the liberal arts curriculum by increasing the range and number of upper-level humanities courses available to their students. Administrators’ motivations echoed their faculty but they were also interested in the possibility of using online instruction as a way to contain costs.

Summary of Findings

We report detailed analyses of the second year’s findings in the following sections. Several high-level findings stand out:

- On surveys administered after the second course iteration, almost all instructors reported that their courses were more successful in the second year than they were in the first year, and that they were better able to use online tools to enhance learning.

- Instructors spent less time planning and delivering their courses in the second course iteration than in the first, and many instructors found the workload much more manageable.

- Enrollment in courses during the second iteration was commensurate with enrollments in humanities face-to-face courses (as reported on surveys) and on par with enrollment in the first course-iteration (measured via course enrollments).

- Students ranked course scheduling, major requirements, and interest in the professor as their top reasons for enrolling in Consortium courses.

- Cross-enrollment presented a substantial challenge, and 40 percent of the courses in the second iteration had no students enrolled from other institutions.

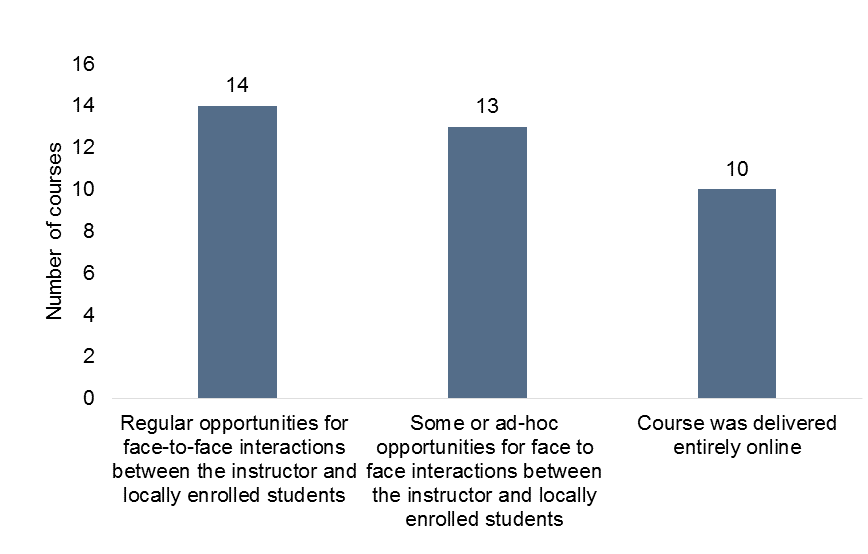

- As a result of no cross-enrollment, faculty integrated face-to-face elements into many courses, and only ten courses were delivered fully online. Resistance from non-participating faculty members was the primary challenge in mobilizing cross-enrollment. In some cases, non-participating faculty restricted advertising of consortium courses to students, expressing concerns that outside courses would exacerbate low enrollment in the colleges’ own courses.

- Students performed well in their courses, and faculty and peer assessors ranked student learning favorably. Multiple pieces of evidence suggest that student learning in Consortium courses was on par with student learning in traditional in-person courses, and some students and instructors reported that certain aspects of the learning experience were enhanced by online tools.

- Despite promising findings about student learning, many students and instructors expressed concerns about the loss of personal interaction or real-time discussion in online courses. In some cases, lack of interaction was associated with small class size or a particularly disengaged group of students, which could also be problematic in a traditional format, but, in other cases, it seemed that the online format was a significant impediment to fruitful dialogue.

- Overall, instructors and students reported that they had a positive experience participating in the Consortium, and most said that they would participate in an online or hybrid course again

Data Sources

In order to assess the Consortium’s success in achieving each of its explicit goals, we collected data from multiple sources. These include:

- Instructor survey [N=37]. This survey was administered at the end of the spring 2016 term. Sections related to student experience in the online course were derived from the Community of Inquiry survey instrument, which focuses on three constructs: instructor presence, social presence, and cognitive presence.[3] The survey was very similar to the one administered in 2015, with some additional questions about instructors’ experiences teaching cross-enrolled students. All but one instructor who taught a course in the second iteration completed the survey. The instructor who did not complete the survey team-taught her course with another instructor, so all courses are accounted for. The survey instrument is included in Appendix B.

- Instructor timesheets [N=34]. Instructors completed and submitted timesheets at two points in time: the end of the planning stage (January 2016) and the end of the spring semester (June 2016). Instructors could continue to categorize time as course planning and design during the spring semester.

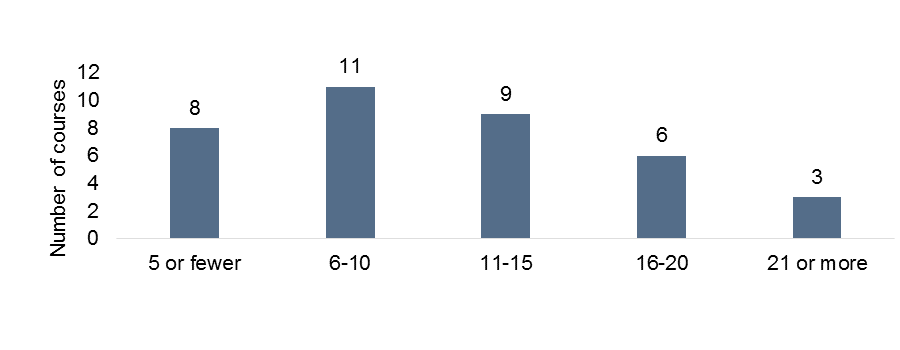

- Student surveys [N=110]. Students in twenty-five of the thirty-seven courses submitted surveys. Each course had between one and nineteen responses, with an average of five responses per course. Of the surveys submitted, twenty-nine came from courses with regular opportunities for face-to-face interaction among locally-enrolled students; fifty-six came from courses with some or ad-hoc opportunities for face-to-face interactions among locally-enrolled students; and twenty-five came from entirely online courses. Eighteen surveys were submitted by cross-enrolled students. Like the faculty survey, sections of the student survey were also derived from the Community of Inquiry survey instrument and have a number of items that are similar to the instructor survey. Surveys were administered by Ithaka S+R on a third-party platform, but instructors coordinated their students’ participation. The student survey instrument is included in Appendix C.

- Faculty panel assessment scores [N=33 artifacts, 156 scores]. Three instructors assessed a sample of student work on two generic learning outcomes—students’ ability to interpret and analyze texts, and students’ ability to synthesize knowledge. The sample of student work was comprised of three, randomly-selected artifacts from ten of the thirty-seven courses. Assessors ranked students on a four-point scale (Beginning, Developing, Competent, Accomplished). The rubric, with a full description of the learning outcomes, is included in Appendix D.

- Completion and Grade Data [N=206 students]. Each institution’s registrar provided data on the number of students in each course and anonymized student-level data on students’ majors, course grades, and whether the course counted towards students’ majors. We received this information from seventeen of the 21 institutions.

- Supplemental Qualitative Data [N=5 instructors, 4 administrators, 3 Registrars]. We conducted 1-hour interviews conducted with instructors, administrators, and registrars at 10 institutions to capture more in-depth and nuanced information on the experiences of participants in the Consortium. A list of interviewees and interview scripts are included in Appendix E.

Rather than present findings from these sources separately, we integrate them in our analysis to provide a more holistic picture of the Consortium’s second year.

Limitations of the Study

There are several methodological and empirical features of the study that limit our ability to draw firm conclusions in some areas. Specifically:

- There is no standardized assessment tool that met the Consortium’s needs for the types of learning outcomes expected of upper division humanities courses. Consequently, there was no objective, widely accepted way to measure or compare student learning in Consortium course with that of traditionally taught courses.

- It was not possible to implement the methods used to measure student learning outcomes in Consortium courses in comparable traditionally taught courses. Our judgment of the comparison between the quality of student learning in online/hybrid courses and traditionally taught ones is thus based primarily on subjective assessments from instructors triangulated with course grades and panel assessments of student artifacts using a standard rubric.

- The interpretation of student survey responses is hindered by low response rates. One-third of courses had a response rate of zero. On 20 surveys, students only responded to five or fewer items.

- The cost data are based only on estimates of instructor time use, which instructors submitted at varying points throughout the semester (i.e., some instructors reported time every week; others sent estimates of total time spent at the end of the semester). Our interviews, surveys, and instructor time sheets give us a sense of the demands placed on support units, but these measures do not capture specific costs related to technical infrastructure and bandwidth.

Goal 1: Building Capacity

At the outset of this project, many of the participating institutions had little experience with online learning. To measure the extent to which these institutions increased their capacity for online instruction, we asked three questions: (1) Did instructors increase their capacity to use online tools to effectively deliver instruction? (2) Did institutions increase their capacity to support students and instructors who were involved in online and hybrid courses? And (3) did member institutions collectively and collaboratively increase their capacity to offer humanities courses to students at other Consortium schools?

Did instructors increase their capacity to use online tools to effectively deliver instruction?

In the second year of the Consortium, thirty-seven courses were offered. This represents three fewer courses than the previous year: one course was cancelled due to low enrollment; another was cancelled because the instructor is no longer with his institution; and the third was converted to a face-to-face course because no students were cross-enrolled, and the instructor requested that his course be excluded from the analysis. While all of the courses included in this report offered some instruction online, fourteen courses included “regular opportunities for face-to-face interactions between the instructor and locally enrolled students;” thirteen included “ad-hoc” opportunities for face-to-face interactions, and ten were offered fully online (see Figure 1). One course was team-taught by two instructors from two different institutions.

Figure 1: Course Format

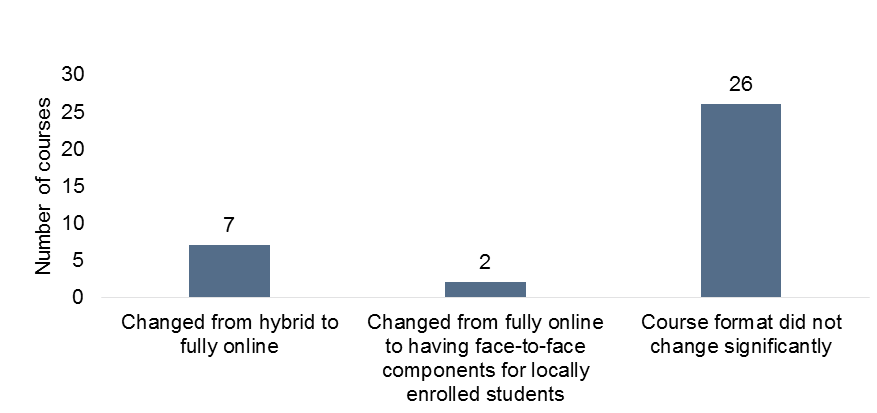

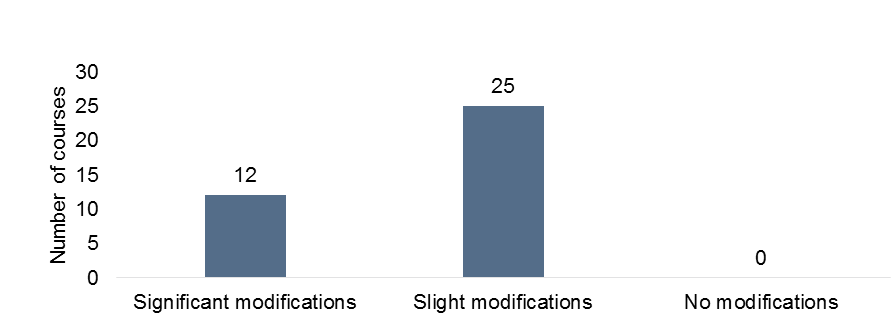

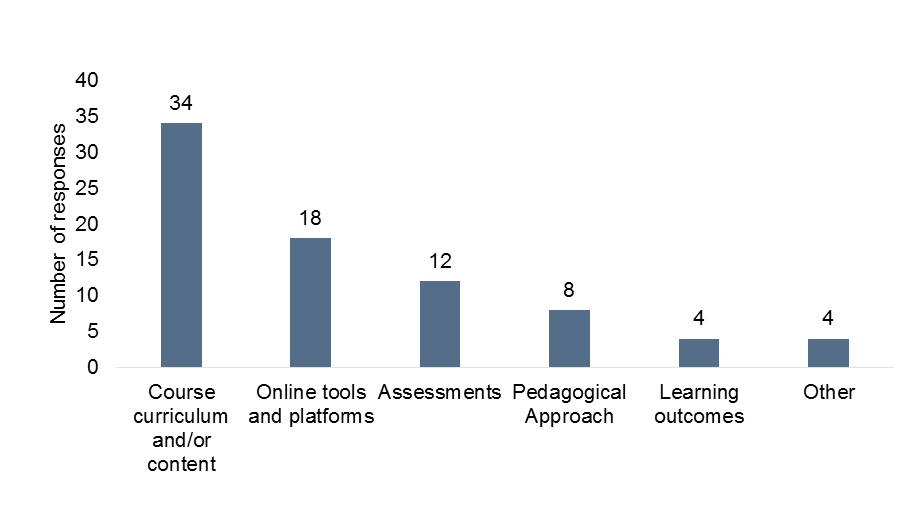

While 26 instructors reported that they did not change the format of their course (e.g. online or hybrid) substantially from the first to the second iteration (see Figure 2), most made modifications to some aspects of their courses: thirty-four instructors reported making changes to curriculum and course content, eighteen reported making changes to online tools and platforms, and twelve reported making changes to the assessments used in their courses (see Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 2: Format Changes from Year 1 to Year 2

Figure 3: Extent of Modifications

Figure 4: Course Components Modified

We used survey and interview responses about instructors’ experiences to assess instructors’ effectiveness at delivering instruction online. Like last year, instructors used a wide range of technologies in their courses. They relied on features available through standard learning management systems such as Blackboard, Canvas, Moodle, and Jenzabar. They also incorporated video conferencing and communications tools such as BlueJean, Voicethread, Zoom, and AdobeConnect (which received poorer reviews); content sharing tools like YellowDig (which one instructor gave glowing reviews for the way it facilitated student learning and discovery); screencast tools like Screencastomatic and Camtasia; and other interactive tools like TimeToast and Thinglink. Not surprisingly, at least half of all participating instructors relied on commonly used sites such as Skype, Spotify, WordPress, YouTube, and Twitter and reported that they worked well. At least seven instructors used Google applications for collaborative student work and generally found these to work well.

We used survey and interview responses about instructors’ experiences to assess instructors’ effectiveness at delivering instruction online. Like last year, instructors used a wide range of technologies in their courses. They relied on features available through standard learning management systems such as Blackboard, Canvas, Moodle, and Jenzabar. They also incorporated video conferencing and communications tools such as BlueJean, Voicethread, Zoom, and AdobeConnect (which received poorer reviews); content sharing tools like YellowDig (which one instructor gave glowing reviews for the way it facilitated student learning and discovery); screencast tools like Screencastomatic and Camtasia; and other interactive tools like TimeToast and Thinglink. Not surprisingly, at least half of all participating instructors relied on commonly used sites such as Skype, Spotify, WordPress, YouTube, and Twitter and reported that they worked well. At least seven instructors used Google applications for collaborative student work and generally found these to work well.

These data indicate that most Consortium members were able to marshal a diverse set of resources to support online instruction, even in institutions with relatively little experience providing undergraduate courses online. This was the case in both course iterations, with slightly more diversity in the tools used in the second year.

Instructors also relied on a wide variety of instructional techniques and project types, many of which received varied reviews. When asked which instructional approaches worked particularly well, 11 instructors described some sort of collaborative group project and 18 instructors referenced the use of discussion boards as particularly useful in prompting engagement. Reviews of these techniques, however, were mixed. Six instructors said that group work was strained in the online format, and a few explained that the absence of face-to-face interaction stifled accountability and peer engagement. Thirteen instructors struggled with discussion boards, saying that responses lacked depth or dialogue felt inauthentic.

On survey responses and at the final workshop, several instructors said that the online format pushed them to be creative and to expand their pedagogical approaches. This is made evident in some of the innovative projects the instructors used in their courses: one instructor used a three-week online debate; another used a witch trial simulation (for a class on witchcraft on British literature). Students in a class on pilgrimages in the post-modern world conducted and presented on their own pilgrimages, and students in a history class had the opportunity to synchronously chat with the author of a book they had read for the class. In a history methods class, students used YellowDig, a social learning platform, to create a repository of relevant resources that they had found in their own research, and engaged in discussions and debates about the resources that they had discovered.

Finally, instructors used asynchronous learning approaches with varying levels of success. While three instructors said that making lectures available to students at the beginning of the term and keeping them available throughout were some of their most successful instructional choices, five said that asynchronous lectures were some of the least successful aspects of their course. In a characteristic comment, one instructor wrote:

“I found that, because of the asynchronous environment, it was difficult to take advantage of those spontaneous teachable moments that arise from things that students say in discussions.”

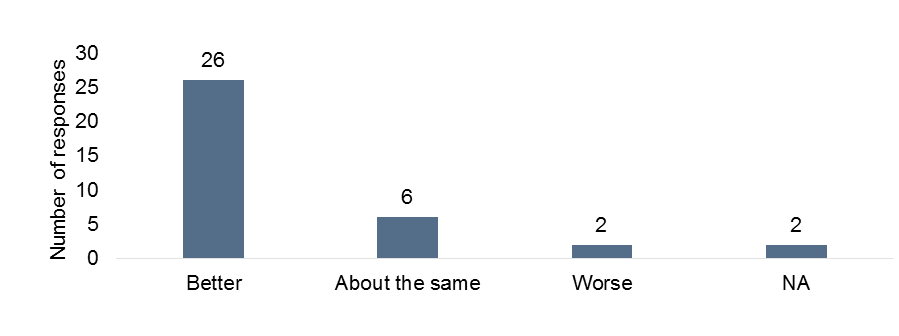

Though, similar to last year, instructors reported instructional challenges and frustrations with technology, open-ended survey responses indicate that instructors did increase their capacity to effectively use the online format for their courses in the second course iteration. When asked to describe how teaching in an online or hybrid format in the second course iteration differed from the first, twenty-six instructors commented that the course went better or much better, and only two reported that the course was worse (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Instructor Experience in Year 2 vs. Year 1

*Based on coded instructor comments.

*Based on coded instructor comments.

Half of the instructors who said that their courses were better the second time explicitly attributed these improvements to their increased experience in and exposure to online instruction. One instructor commented:

“[The course went] so much better. The information I took from the first iteration informed my class structure this semester. There was less modifying throughout the semester. I was able to update current information each week and grade each week. The students were much more prepared each week that we met F2F because they had completed the online lectures and research. I was also able to keep material I threw out last iteration because the students felt overwhelmed.”

Another said:

“I incorporated what I learned from the first iteration relative to designing online assignments/activities that really exploited the learning situation and tools, rather than simply taking things I would have done f2f and placing them online. I challenged myself to think more about the match between the desired outcome of an assignment/activity and the online context for learning.”

And another:

“I was unsure if the changes that I put into place would be effective, but they were. I know that I enjoyed teaching the course [more] this time around, as compared to the first time that it was offered. I believe that the students enjoyed it more as well.”

Instructor comments on other parts of the survey also indicated a growing level of comfort, confidence, and creativity with the online tools. One instructor commented that the most satisfying aspect of teaching in an online or hybrid format was the opportunity to get a “better sense of mastery of technological pedagogy,” while another said it was “the opportunity to try creative assignments such as social media and trial role playing assignments and the compilation of a magazine based on aspects of the course.” Still, as we discuss in the next section, many instructors expressed frustration with the apparent limitations the format placed on their ability to form personal connections with their students.

Certainly, some of the increased effectiveness that instructors reported was the result of additional experience teaching the course content, and would have been apparent in any course’s second iteration, regardless of format. However, as some of the included quotations indicate, we also found evidence that instructors increased their specific capacity to use online tools and the online format to enhance student learning and engagement. Three reported that they were able to reuse resources (such as online lectures) in ways that were specific to the online or hybrid format, and many also indicated that they were continuing to think about how they might better leverage the online format in the future. When asked how they would change their course if they were to offer it for a third time, instructors said they would be more comfortable putting a larger portion of their course online, would incorporate more multimedia materials and activities, would think through how to make online interactions more social, and would explore new tools and pedagogical techniques for online learning.

In the next section, we discuss some institutional resources that instructors may have used to increase their effectiveness at teaching online. However—in addition to relying on this institutional support and additional experience teaching their course—instructors also utilized opportunities that grew directly out of the Consortium. In open-ended survey responses and interviews, three instructors commented that the discussions they had at the CIC National Workshop in August 2015 were helpful in prompting them to reflect on their pedagogy, learn about new tools, and build their capacity to effectively teach online. All five of the instructors we interviewed noted that they worked closely with the other participating instructor at their institution and that they found this relationship very valuable for learning about new tools and instructional techniques. Both of these findings suggest that the Consortium played a crucial role in increasing instructional capacity.

Did institutions increase their capacity to support instructors and students involved in online and hybrid courses?

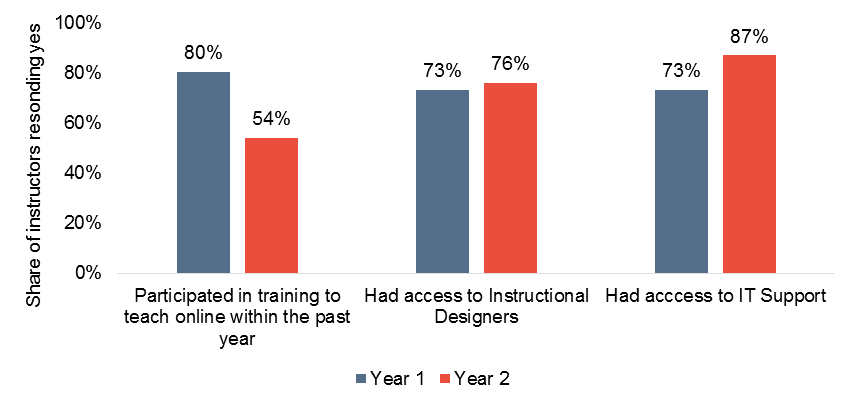

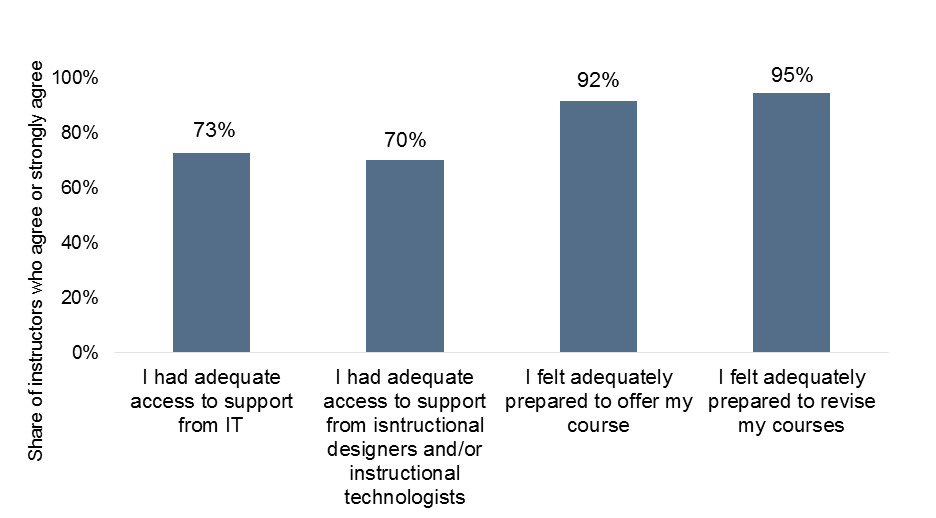

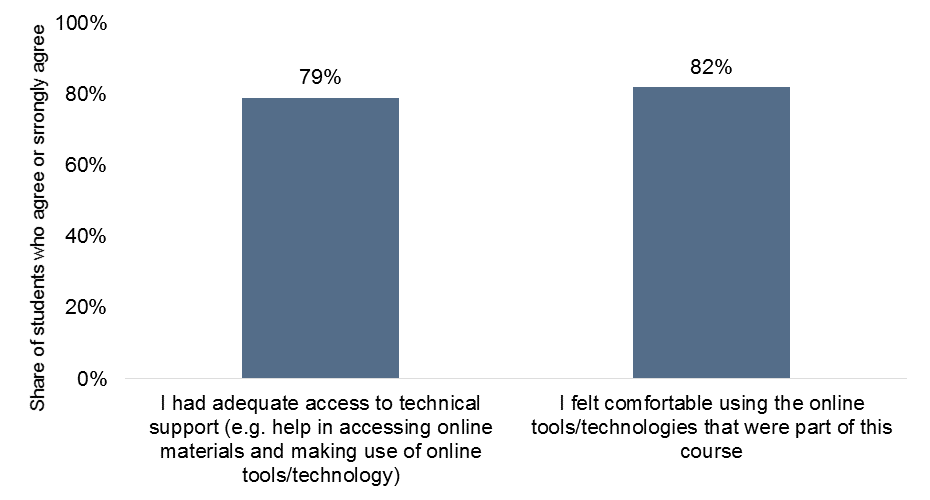

In assessing institutional capacity to support instructors engaged in online teaching, we relied on survey questions about instructors’ access to training, IT, and instructional designers. We saw little change from the first course iteration to the second course iteration in the share of instructors who reported that they used or had access to instructional designers (though baseline accessibility was high). Substantially larger shares of instructors said they had access to IT support in the second course iteration. Fewer instructors reported that they participated in training for the second course iteration than for the first, though this should not be surprising since all but one instructor had taught their course in an online or hybrid format in the previous year (see Figure 6). Instructors report that their training usually consisted of tutorials for different tools (e.g., learning management systems and content management systems) and college-provided training for online learning and pedagogy.

Figure 6: Institutional Support for Instructors

Only four instructors said they experienced technical challenges in planning, revising, or teaching the course, and the vast majority felt adequately prepared to revise and offer their course (see Figure 7). A majority of students also felt adequately supported, and felt comfortable using the technology tools needed to complete the course (see Figure 8). These patterns were very similar to those that emerged during the first course iteration.

Figure 7: Instructor Preparation and Perceptions of Support

Figure 8: Student Perceptions of Support

While these data indicate that institutions have the capacity to help instructors and students navigate through the technical challenges involved with online teaching and learning, they do not provide a holistic picture of institutional readiness to support online instruction. In many of our interviews, we heard that many non-participating humanities faculty were skeptical about the efficacy of online learning, and that some saw online courses as “watered-down” versions of face-to-face ones. As we discuss in the next section, these attitudes were a barrier to promoting courses for cross-enrollment. Fortunately, several interviewees said that their institution’s participation in the Consortium had helped to soften on-campus resistance: once faculty members saw that online courses could be conducted without compromising learning, some warmed up to the idea. One institution had some of its most experienced and well-respected instructors teach the Consortium courses, and, as a way of increasing capacity and allaying skepticism, is planning to have its Consortium faculty hold seminars about online learning with faculty in their departments.

Did member institutions collectively increase their capacity to offer humanities courses to students at Consortium schools?

One of the major premises of the Consortium is that liberal arts institutions—limited in their capacity to offer humanities courses because of small departments and constrained budgets—can collectively increase their capacity to serve humanities students by offering courses through a consortium. Doing so would provide humanities students with more options for fulfilling degree requirements and may free up faculty members to teach new courses.

In order to assess whether member institutions collectively increased their capacity to serve humanities students, we analyzed enrollment data, survey responses, and asked instructors, administrators, and registrars about their experiences working with member schools to cross-enroll and support outside students. Though no decisive picture emerged from these data, it does seem that institutions—and the Consortium at large—face some significant logistical and cultural challenges in achieving this goal.

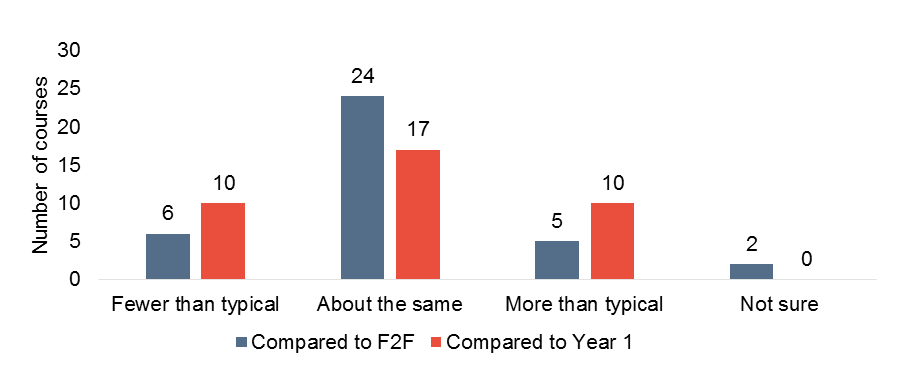

The Consortium enrolled 402 students this year. Nearly 80 percent of these students were juniors or seniors and about half were taking an online or hybrid course for the first time (this breakdown was similar to last year’s, with a slightly larger share of students with experience taking an online course). On average, consortium courses enrolled about 11 students, with a minimum of two students, a maximum of 25 students, and a standard deviation of six students. Like they did on last year’s surveys, instructors reported that enrollment in their courses was about the same as average enrollment in face-to-face courses. Instructors also reported that enrollment in their second course iteration was about the same as enrollment in their first course iteration (see Figure 10).

Figure 9: Student Enrollment Ranges (Total)

Figure 10: Enrollment Comparisons

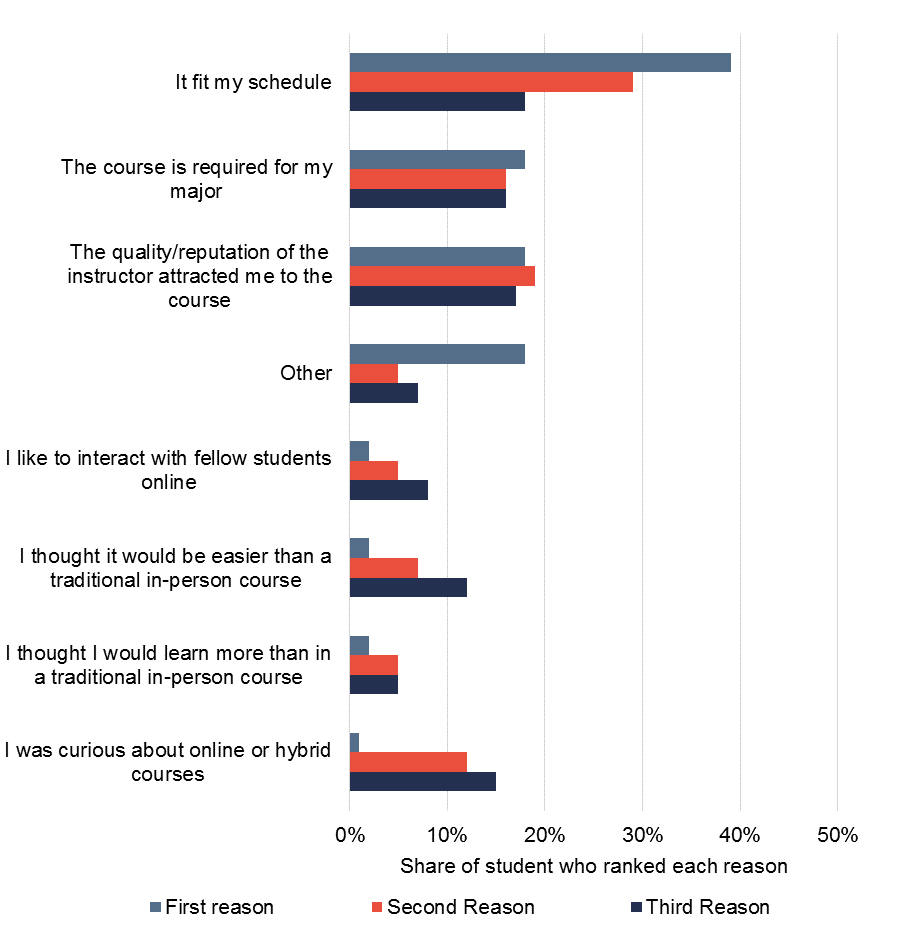

When asked to rank the reasons that they enrolled in the Consortium course, students overwhelmingly chose “fit in their schedule” as the primary reason. Many students also indicated that they took the course because it was required for their major or because they were attracted to the quality and reputation of the instructor (see Figure 11). These reasons were also highly ranked for the first course iteration. Registration data for 206 students confirms that 32 percent of these students took a course that fulfilled a major requirement.

Figure 11: Students’ Reasons for Taking Course (Full Sample)

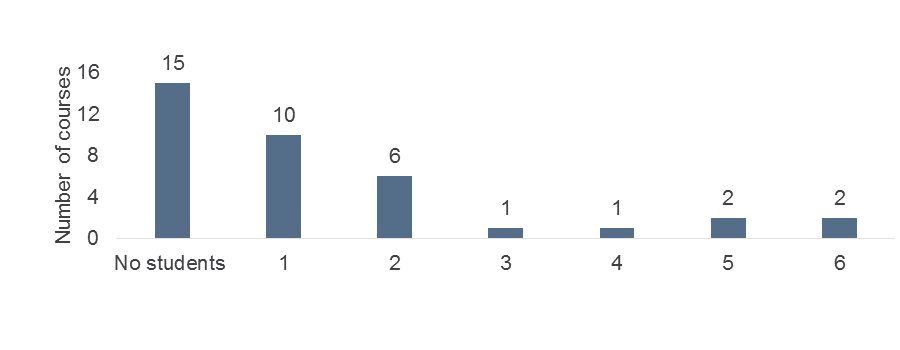

Though Consortium course enrollments were commensurate with traditional course enrollments, most institutions faced substantial difficulties in cross-enrolling students in their courses. Of the thirty-seven courses offered this semester, fifteen courses had no cross-enrolled students. To varying degrees, instructors who taught these courses adjusted the formats to hybrid or face-to-face to accommodate locally-enrolled students. Among the other courses offered, ten courses had one cross-enrolled student, and six courses had two cross-enrolled students. Four courses had five or six cross-enrolled students; two of these courses were at the same institution (see Figure 12).[4] There were no noteworthy patterns in the subject matter of courses with more cross-enrolled students, and larger courses did not tend to have more cross-enrolled students than smaller ones.

Figure 12: Student Enrollment Ranges (Cross-Enrolled from Other Institutions)

Though few cross-enrolled students completed the survey, those who did cited the same reasons for enrolling as did the full sample, with scheduling as the most highly ranked reason and the fulfillment of a major requirement as the second most highly ranked reason. Four students also commented that they took the course because it was not available at their home institutions and that they enjoyed having access to a broader range of courses. Unfortunately, institutions did not collect information about whether cross-enrolled students enrolled in courses that counted towards their majors, so we do not know how many students, in total, were able to complete major requirements through cross-enrollment opportunities. Registrars we interviewed said that this could be remedied by the creation of a shared Consortium form that all institutions could use for collecting standardized information about cross-enrolled students.

Though few cross-enrolled students completed the survey, those who did cited the same reasons for enrolling as did the full sample, with scheduling as the most highly ranked reason and the fulfillment of a major requirement as the second most highly ranked reason. Four students also commented that they took the course because it was not available at their home institutions and that they enjoyed having access to a broader range of courses. Unfortunately, institutions did not collect information about whether cross-enrolled students enrolled in courses that counted towards their majors, so we do not know how many students, in total, were able to complete major requirements through cross-enrollment opportunities. Registrars we interviewed said that this could be remedied by the creation of a shared Consortium form that all institutions could use for collecting standardized information about cross-enrolled students.

Instructors and institutions faced several challenges in cross-enrolling students. Some of these were logistical or technical. For example, one survey respondent from Hiram College explained the difficulties of each institution having different registration periods and academic calendars:

“I think we were unable to recruit any students from other institutions in part because our registration period is earlier than that of other colleges in the consortium. Students at other institutions were not signing up for courses when our registration was in progress. We also need to do more outreach to publicize the program for our students and for students at other institutions. Our course calendar is also different from that of other colleges. We have a 12-week semester. I think we need to find ways to work around these differences in calendars between institutions.”

All three of the registrars we interviewed also lamented that there was no standardized process across the consortium for institutions to list courses in their catalog or mark courses on their transcript, and wished that there had been more and earlier coordination and cooperation among registrars. Consistently, interviewees in instructor, administrator and registrar roles wondered if there might be a stronger role for CIC to play in coordinating activities around cross-registration.

While technical and logistical challenges posed barriers to enrollment, most of the instructors, administrators and registrars we interviewed said that these difficulties were manageable. Many institutions were already part of local or regional consortia, so had policies and forms to accommodate students who were registered at other institutions, and technical issues regarding access to an institution’s LMS, different time zones, and assignment submission were easily resolved.

Less manageable than technical and logistical challenges, however, were cultural ones. Multiple instructors, registrars, and administrators noted that marketing and promoting their courses was a challenge because other, non-participating faculty members were resistant to the idea of course-sharing. According to the consortium members who we interviewed, non-participating faculty expressed concerns that promoting Consortium courses might draw students away from their own courses, which were already facing low-enrollments, and result in departmental cuts. As a result, several non-participating faculty did not promote the courses to their advisees, and some departments refused to count credit from other institutions towards major requirements. Some wondered if organizing the Consortium around core requirements that are often similar across institutions—while potentially more cost effective—might compound this anxiety.

Goal 2: Enhancing Student Learning

As with our exploration of institutional and instructional capacity, we examined student learning in three parts. First, we asked: were students engaged in high-quality learning and did they achieve the intended learning outcomes for their courses? Second: did the courses succeed in fostering interpersonal interactions and building a strong sense of community? And third: how did student learning in the online/hybrid courses compare to learning in traditional face-to-face instruction? We realize that each of these questions is intertwined with the other two: it is hard to talk about engagement and community in an online format without comparing it to face-to-face experiences. Additionally, learning in the humanities in inextricable from elements like collaboration, discussion, and community.

Were students engaged in learning and did they achieve the intended learning outcomes for their courses?

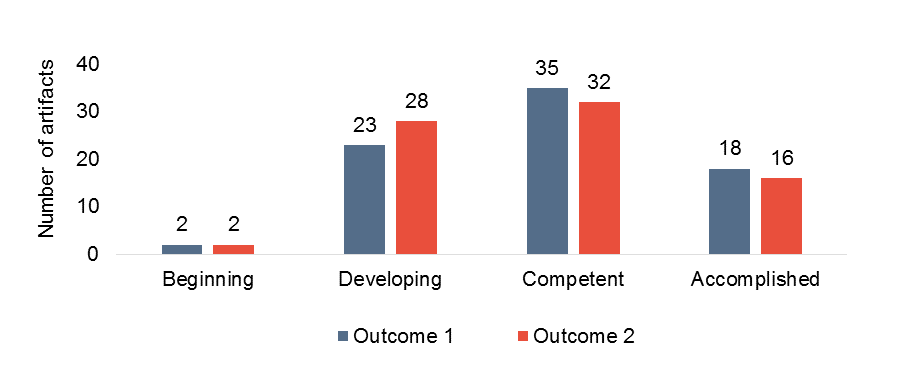

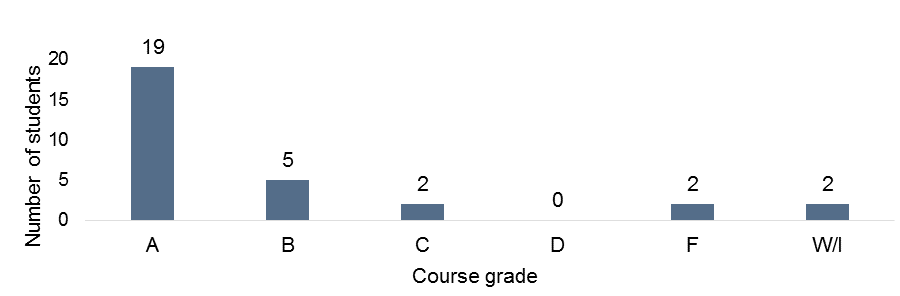

Course grades, survey responses, and analyses of learning outcomes by a panel of Consortium faculty suggest that, by and large, students did achieve the intended learning outcomes for their courses. Panel assessments, which were conducted by three participating faculty, yielded the least promising results, though these results were very similar to last year’s. Assessors rated randomly selected student artifacts as “Beginning,” “Developing,” Competent,” or “Accomplished,” for two generic learning outcomes. The first learning outcome assessed students’ ability to interpret meaning and the second assessed students’ ability to synthesize knowledge. Out 156 scores on thirty-three artifacts, 22 percent were scored as “Accomplished;” 43 percent were scored as “Competent;” 37 percent were scored as “Developing;” and only 3 percent were scored as “Beginning.” These results were fairly consistent across the two learning outcomes on which students were scored (see Figure 13).

Figure 13: Assessor Scores on Learning Outcomes

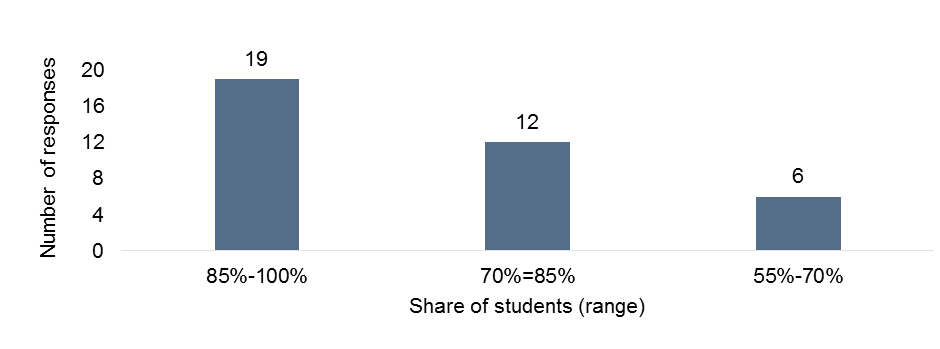

Instructors rated their students more highly than did panel assessors, and most reported that their students achieved course-specific learning outcomes. When asked on the instructor survey, “what percentage of students met or exceeded learning expectations” as defined by instructors’ own specified learning outcomes, nineteen instructors said 85 percent to 100 percent of their students met or exceeded expectations, and twelve said 70 percent to 85 percent met or exceeded learning expectations (see Figure 14). When applicable, instructors reported no perceived difference in performance between locally and cross-enrolled students (though one instructor said that her advisees struggled with the rigor of courses at other institutions). Course grades reported by registrars corroborate that cross-enrolled students tended to perform well in the courses, with no noticeable differences between their grades and those of locally enrolled students.

Instructors rated their students more highly than did panel assessors, and most reported that their students achieved course-specific learning outcomes. When asked on the instructor survey, “what percentage of students met or exceeded learning expectations” as defined by instructors’ own specified learning outcomes, nineteen instructors said 85 percent to 100 percent of their students met or exceeded expectations, and twelve said 70 percent to 85 percent met or exceeded learning expectations (see Figure 14). When applicable, instructors reported no perceived difference in performance between locally and cross-enrolled students (though one instructor said that her advisees struggled with the rigor of courses at other institutions). Course grades reported by registrars corroborate that cross-enrolled students tended to perform well in the courses, with no noticeable differences between their grades and those of locally enrolled students.

Figure 14: Share of Students Who Met or Exceeded Learning Expectations

Figure 15: Course Grades (Full Sample)

*Course grades were reported for 202 students. W/I stands for Withdraw or Incomplete. Counts for each letter grade include all possibilities for that letter grade (e.g. A’s include A+’s and A-’s).

Figure 16: Course Grades (Cross-Enrolled Students)

*Course grades were reported for 31 cross-enrolled students. W/I stands for Withdraw or Incomplete. Counts for each letter grade include all possibilities for that letter grade (e.g. A’s include A+’s and A-’s).

*Course grades were reported for 31 cross-enrolled students. W/I stands for Withdraw or Incomplete. Counts for each letter grade include all possibilities for that letter grade (e.g. A’s include A+’s and A-’s).

In an open-ended survey question about which aspects of the course instructors found most satisfying, five instructors explicitly commented on the favorable quality of student work and explained that students seemed to have thought critically about course material and understood course concepts. For example, one instructor wrote:

“I was most satisfied by the excellent written work by the online students. It was fascinating to teach texts I’ve taught many times in this new format.”

Another commented:

“I was happy to see that when students worked through the course modules, did the required deep reading and listening, and took time to internalize the material, they were able to make the kinds of historical and critical distinctions and analysis I would expect from any face-to-face course.”

And another:

“The final essays, in which the students reflected on what they learned and discussed the benefits and limitations of the overarching conceptual framework of the course showed the development insight and appreciation among all of the students (the highly and less highly engaged). This was incredibly rewarding at the end of the semester.”

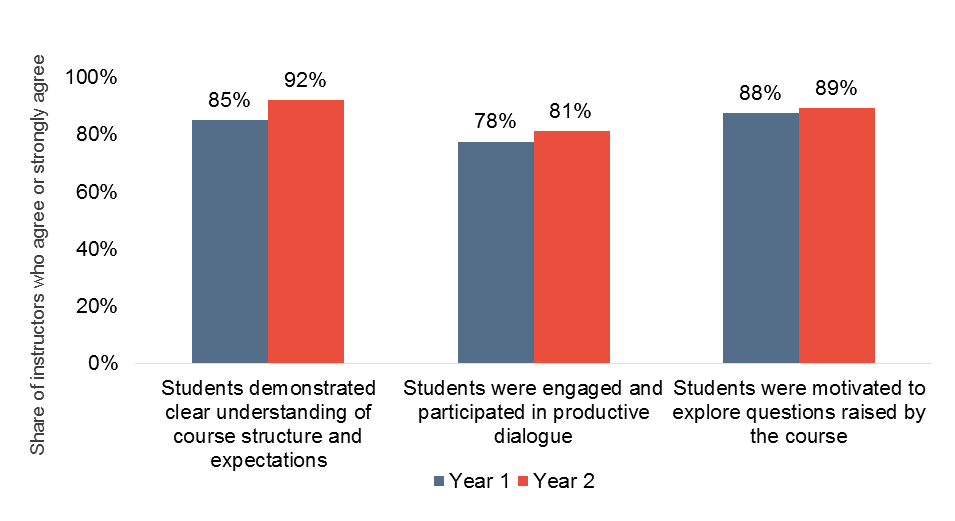

Just as instructors and panel assessors felt that students generally achieved the intended course outcomes, so too did instructors find that students were motivated and engaged with course material. On the instructor survey, more than 80 percent of instructors agreed or strongly agreed that students were motivated to explore questions raised by the course, that students were engaged and participated in productive dialogue, and that students demonstrated a clear understanding of course structure and expectations. This represents a slight increase from instructor responses in this area after the first year of courses (see Figure 17).

Figure 17: Instructor Ratings of Student Engagement

Instructor comments corroborate these findings, and fourteen instructors reported that seeing their students engage, in some way, with the material was the most satisfying part of teaching of the course. One instructor said that she enjoyed “seeing students dig deeper into the material and learn more.” Another explained that the most satisfying aspect of the course was:

“…students seeking explanations or news stories on their own and sharing it with the group. It shows me that they are engaged in the material outside of the assigned readings.”

Like last year, instructors also commented that the online and hybrid format allowed for students that might not speak up in face-to-face courses to share their contributions in varied ways. For example, one instructor explained:

“[I was] able to ‘hear’ (read) the contributions of ALL students. I had some students whom I had also taught in face-to-face courses. I knew from experience that these students were very shy and had difficulty contributing to face-to-face class discussions. In the online iteration, they made wonderful contributions to the discussion forums.”

Another instructor explained:

“Students who were not likely to be verbal in a traditional course seemed to be more willing to participate.”

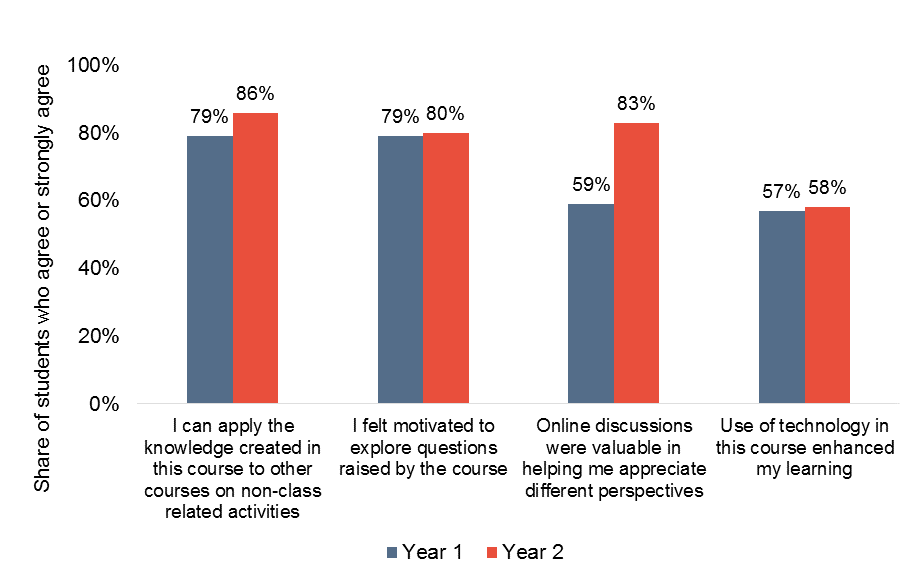

Students also tended to agree that they felt engaged with course materials and had a valuable learning experience. More than 80 percent of student survey respondents agreed or strongly agreed that online discussions were valuable in helping them appreciate different perspectives, that they felt motivated to explore questions raised by the course, and that they could apply the knowledge created in this course to other contexts. While response patters were similar to last year’s, a noticeably larger share of survey respondents (24 percentage points more) thought that online discussions were valuable in helping them appreciate different perspectives (see Figure 18). This seems consistent with other data that suggest instructors were able to use online tools and techniques more effectively during their second course iteration than in the first. Fewer students—though still a majority—agreed that the use of technology in the course enhanced their learning. There was no noticeable difference in responses among locally enrolled and cross-enrolled students.

Figure 18: Student Ratings of Engagement

Student comments about their learning experience were mixed, though some students noted that the flexibility and independence afforded by the online format was conducive to learning. As we discuss in the next section, a few students said they felt they learned more in an online format than in a face-to-face format; however, roughly equal numbers used the open-ended comments to explain that the online format was not ideal for the course subject matter and/or their learning style.

Like instructors, some students felt that they were able to engage more with course content and to perform better in the course because they were more comfortable participating in an online environment. When students who ranked online or hybrid courses as better than in-person courses were asked to explain their answer, six cited increased comfort as part of their answer. One student explained:

“Anxiety slightly inhibits my ability to fully focus in a normal class setting. Taking the course online alleviates the stress of the social component and lets me focus on my studies.”

Another commented:

“I felt less prone to judgment or alienation from peers and could be more open in discussions.”

Though faculty members generally seemed pleased with their students’ performance in the course, about a fifth commented, in their responses to multiple questions that their students did not “buy in” to the online format, and seemed to use the online format to “go through the motions,” rather than engage with course content. As a result, instructors felt that student learning suffered. We have seen this dynamic in past research, particularly when the online and face-to-face components of a course are not well integrated and when students do not understand the rationale behind inclusion of the online part. However, as some instructors noted, fostering engagement and discussion (discussed at more length in the next section) remains a challenge in face-to-face courses as well. The role played by course format versus pedagogical techniques, student dynamics, and other factors, remains unclear.

Did the courses succeed in fostering personal interactions and building a strong sense of community?

Evidence about student engagement and community points in multiple directions, as it did the first time that the Consortium courses were taught. Many instructors and students expressed surprise at how well they were able to build a community and foster engagement in their courses, but others expressed dissatisfaction with the online format as a medium through which to foster the interactions necessary for engaged learning in the humanities. While scaled survey responses suggest the former conclusion, instructor and student comments provided a more nuanced picture that includes both successes and frustrations. Overall, however, both instructors and students felt as if community and personal relationships were better achieved in the second course iteration than in the first.

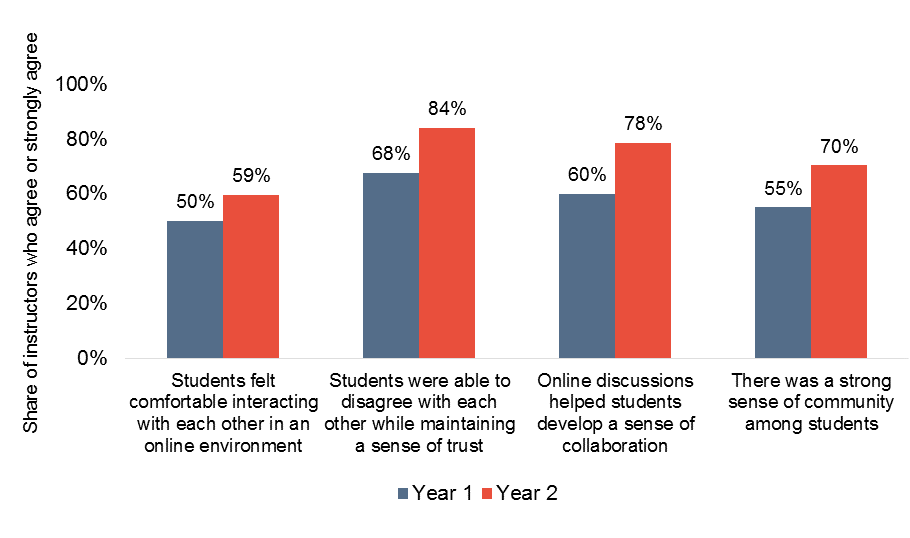

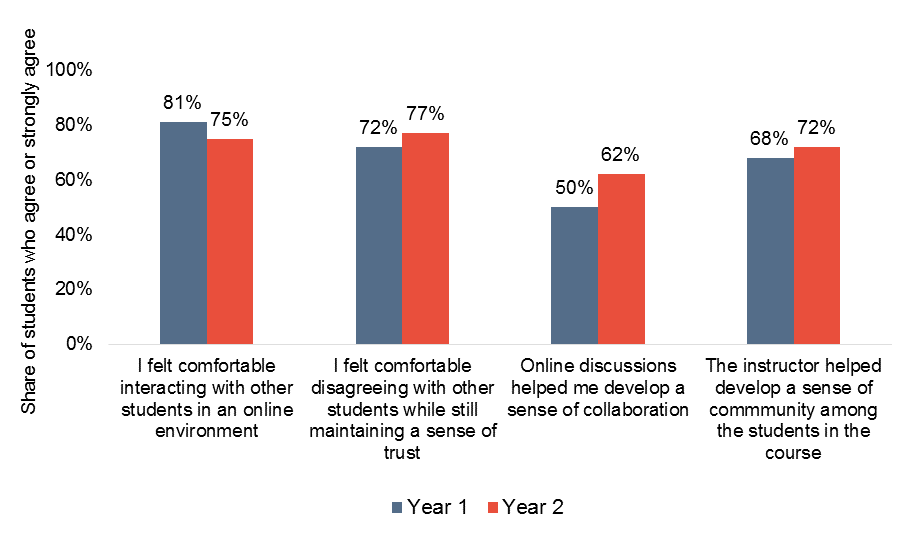

On survey questions that asked instructors and students to rank the extent to which they agreed with a number of statements about community, social presence in the online/ hybrid environment, large shares agreed that Consortium courses fostered a strong sense of community, collaboration, and trust. Promisingly, slightly larger shares of instructors and students agreed with most of these statements in the second course iteration than in the first. In particular, 78 percent of instructors thought that online discussions helped students develop a sense of collaboration in year 2, while 60 percent agreed or strongly agreed with this statement in year 1 (see Figure 19). Similarly, 62 percent of students agreed or strongly agreed that online discussions helped them develop a sense of collaboration in year 2, while 50 percent agreed or strongly agreed with this statement in year 1 (see Figure 20). These results are consistent with other findings shared in this report.

Figure 19: Instructor Ratings of Student Social Presence

Figure 20: Student Ratings of Student Social Presence

While the share of cross-enrolled students who completed the survey is too small to make any conclusive comparisons between this group and the whole sample, it is worth mentioning some differences in response patterns among these two groups. While 75 percent of all enrolled students agreed or strongly agreed that they felt comfortable interacting with other students in an online environment, only 61 percent of cross-enrolled students felt this way. This may be due, in part, to the fact that, in many cases, locally enrolled students had opportunities to engage with one another in-person as well as online. Three cross-enrolled students explained that they felt isolated because they could not meet in-person with the rest of the group, and it is possible this could have contributed to some apparent discomfort.

On the other hand, when compared to the total sample, larger shares of cross-enrolled students said that online discussion forums helped them to develop a sense of collaboration. Again, these comparisons must be taken with a grain of salt due to the vast difference in sample size (nineteen of 110 survey respondents were cross-enrolled), and, perhaps, due to a different self-selection process for students who cross-enrolled.

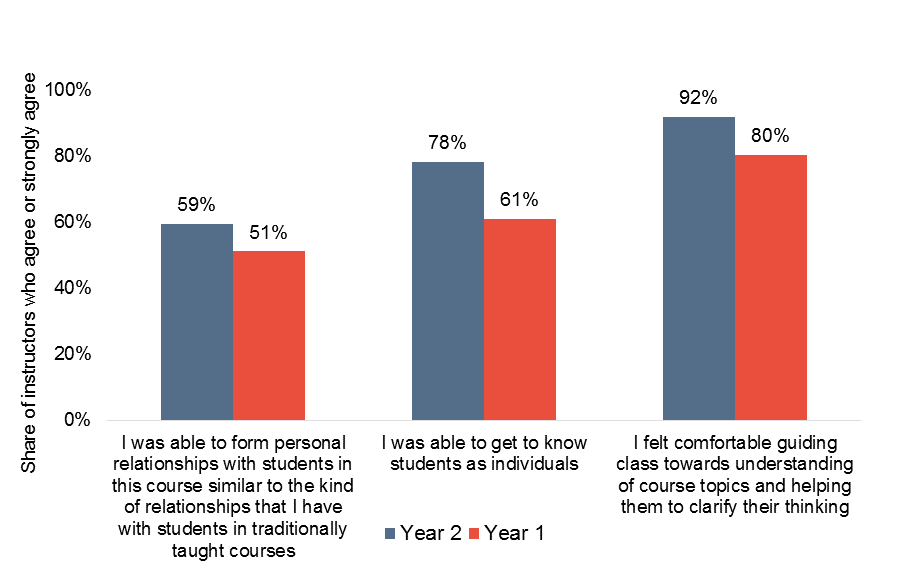

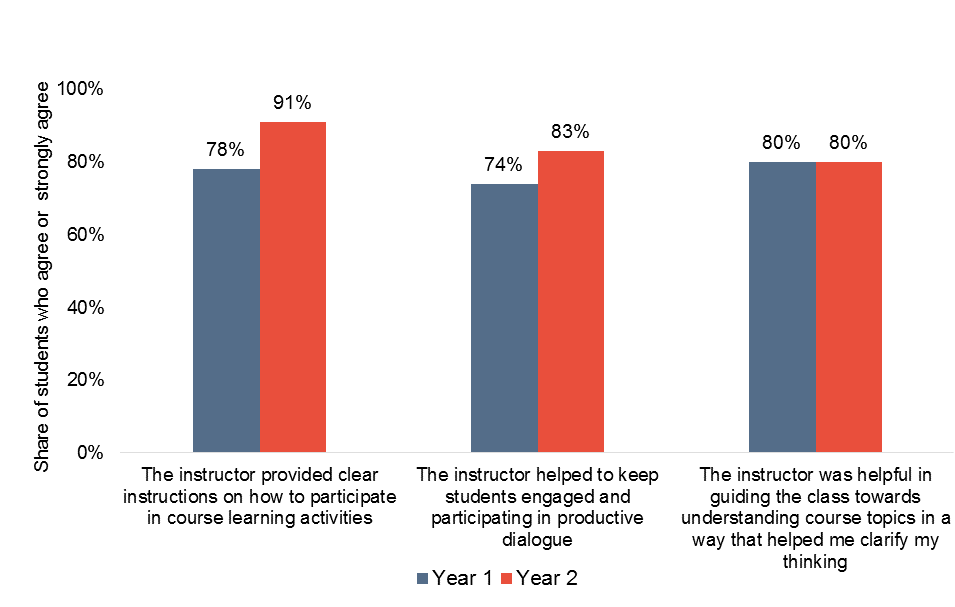

Instructors and students also largely agreed that instructors were able to establish and maintain a social presence in their courses by forming personal relationships with students, getting to know students as individuals, and by helping students engage with course content and one another (see Figures 21 and 22). Again, slightly larger shares of instructors and students felt this way in the second iteration of courses than in the first. Instructors also reported that their online interactions with cross-enrolled students did not differ from their interactions with locally enrolled students, and cross-enrolled students’ responses did not substantially differ on these questions.

Figure 21: Instructor Ratings of Instructor Presence

Figure 22: Student Ratings of Instructor Presence

Instructor and student comments reiterate these sentiments, and instructors report that student discussed course topics with one another with enthusiasm and insight. As in the initial cycle of courses, some students said that they thought class discussions and interactions were better in the online environment than they were in face-to-face settings, largely because shyer students were able to participate. For example, one student commented:

“I felt the discussion online was better than the traditional discussion in the classroom in which people are often shy to share their opinion.”

Instructors used various methods to foster community in their classes. Six instructors said synchronous class sessions worked particularly well. Others had good results with discussion boards, video and audio tools for peer review, and project-based learning. As discussed in the previous section, three instructors said that asynchronous sessions stifled interaction and community.

Promisingly, six instructors said that the most satisfying aspect of their course was being able to develop relationships with students from outside of their institution, and a couple noted that their students learned a great deal from having the opportunity to interact with cross-enrolled students. Cross-enrolled students echoed these opinions.

However, when asked what the least satisfying aspect of teaching in an online or hybrid format was, twenty-one instructors alluded to a lack of community or stifled personal interactions between students and instructors, and/or students and their peers. In particular, instructors seemed especially frustrated with their constrained ability to form personal connections with students in their classes. One instructor commented:

“Throughout the semester, I felt disconnected with my students. We did not form the kind of relationship that I normally do with students in face-to-face courses.”

And another explained:

“I did not get to know the students nearly as well and therefore I was not able to address them as specifically as individuals.”

Students expressed these frustrations as well, and most students who gave courses a low rating or said they would not take a hybrid or online course again cited the lack of community or personal relationships as a primary reason. This was especially true for cross-enrolled students who took courses fully online, while most local students had opportunities to meet in person. For example, one cross-enrolled student commented:

“I didn’t like not being able to engage face-to-face with other students. I felt very distant due to the fact that there were so many that were actually in class and feeling a sense of community and I was not.”

Other students felt that would have benefitted from being able to learn from their professor in person. One student noted that the “magic” of her professor (with whom she had presumably taken a course before) was lost in this format, while another said that, after meeting once with the professor in person, she felt that the course would have been strengthened with more face-to-face interactions.

Despite their frustrations, some instructors attributed limitations on social presence and community building to the types of tools they used or the manner in which they used their tools, rather than the online or hybrid environment in and of itself. Twelve instructors said that if they were to teach their course again, they would make changes such as including more synchronous classes, preparing their discussion forums differently, or would apply new teaching techniques, and three expressed new awareness about the importance of careful planning and preparation for success in an online format. For example, one instructor commented:

“Students respond well to group projects that are well planned and executed. Without the time in the classroom to establish the rapport with each other, the students felt a bit lost when it came to collaborative work. Thus, more planning is called for in advance and more community building activities.”

Still, in response to multiple open-ended survey questions, several instructors said that it was the online or hybrid format itself, rather than the tools and techniques used, that stifled community and generative interpersonal interactions. Because most of these comments compared the online learning experience directly to face-to-face courses, we discuss them at more length in our next section.

How did student learning and engagement in the online/hybrid courses compare to learning in traditional face-to-face instruction?

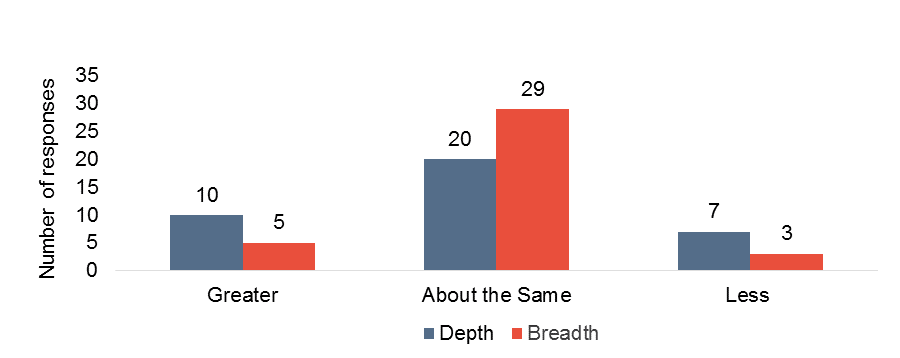

Because we do not have data to compare course grades or student learning outcomes between online or hybrid Consortium courses and their face-to-face equivalents, we cannot make any conclusive comparisons between these formats. The assessors’ scores of learning outcomes indicate that students met their goals for their respective courses, and survey responses from instructors also provide favorable comparisons for the online format. In survey responses, both instructors and students reported that, in general, student learning in the online format was no better or worse than in face-to-face courses, and many said that it was appropriate for certain circumstances or certain types of students (see Figure 23).

Figure 23: Instructor Ratings of Depth and Breadth of Student Learning vs. Traditional Courses

While the majority of instructors believed that the depth and breadth of student learning was about the same in online or hybrid courses as in traditionally taught ones, ten felt that the depth of learning was greater in an online format, and five felt that the breadth of learning was increased. One such instructor wrote:

“I find that students get much deeper into the material in online courses. There is almost a sense in which they feel that they must work harder because it is an online course.”

Another instructor said that the amount that students had to write in online or hybrid courses was greater than what was expected in traditional in-person courses, and that many students therefore emerged from the course as better writers. One instructor appreciated the extra time students could use to reflect and respond to course material or to other students, while two others said that the online format lent itself more to project-based work and independent student discovery. One instructor was particularly pleased with how the format enhanced interactions amongst students, as well as between students and the larger academic community:

“I think the format enhanced the experience in so far as the peer review elements were concerned. I have peer review occurring at all stages of the development process. The tools for online commenting and audio commenting were a value added to the process. Students really did get a lot of feedback that was helpful. I also used the opportunity to bring in and require students to get feedback from other professors. Doing that online made getting this kind of involvement possible.”

Other instructors were more ambivalent, and in response to various comments, several were openly skeptical that the online format could ever replicate the depth of learning achieved in a face-to-face format. In a characteristic response, one instructor wrote:

“I don’t believe that there is any ‘magic bullet’ that will transform a mostly online course to have the same depth of learning that I find occurs in the small face-to-face classroom. Discussion Board can be great, but it rarely is an equal replacement for real dialogue and conversation. The Blue Jeans synchronous classes went well, but five of these over a semester are not a replacement for 3 hours (minimum) face-to-face time. I believe there are other good reasons for students completing some number of online courses; these learning opportunities enhance their skills with self-discipline and follow through, as well as skill in online environments and with digital tools. All this is a good reason to continue with some limited online learning in my (liberal arts) environment.”

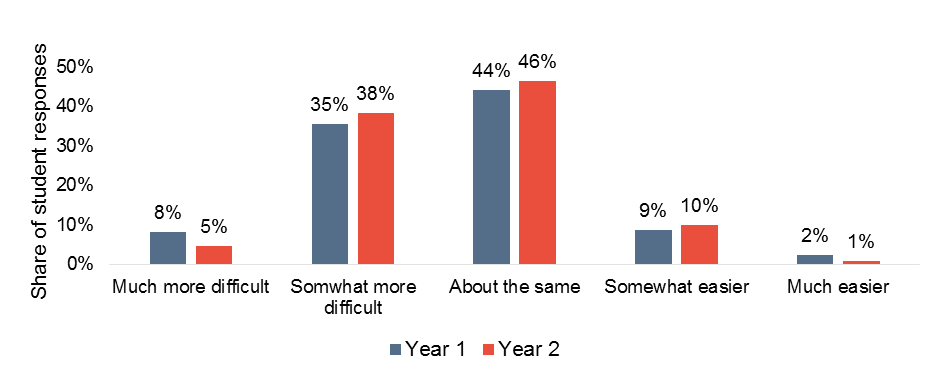

While students were not asked directly to compare their learning to that achieved in traditional courses, they were asked to rank the difficulty of their course as compared to other humanities courses they had taken. Like last year, most students said that their Consortium course was either somewhat more difficult or posed about the same level of difficulty as other humanities courses (see Figure 24). This was consistent across locally enrolled and cross-enrolled students.

Figure 24: Student Rankings of Course Difficulty vs. Face to Face

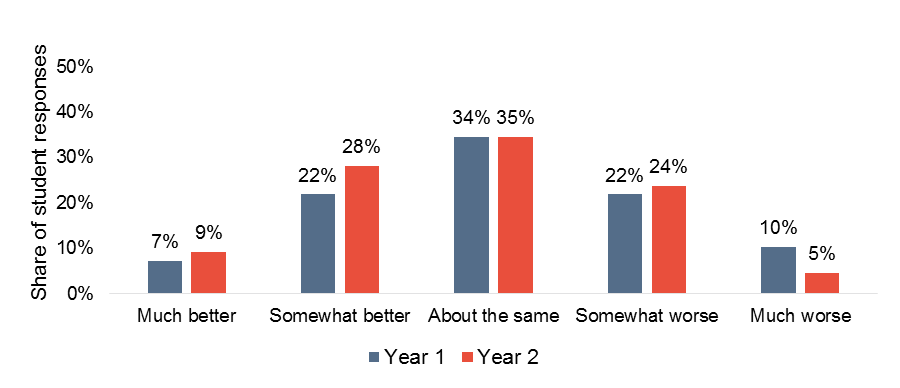

Students also ranked their course experience, overall, to that of traditional face-to-face courses. Like last year, most reported that the course experience was about the same, with roughly equal minorities saying that the course was somewhat better or somewhat worse (Figure 25).

Students also ranked their course experience, overall, to that of traditional face-to-face courses. Like last year, most reported that the course experience was about the same, with roughly equal minorities saying that the course was somewhat better or somewhat worse (Figure 25).

Figure 25: Student Rankings of Overall Course Experience vs. Face to Face

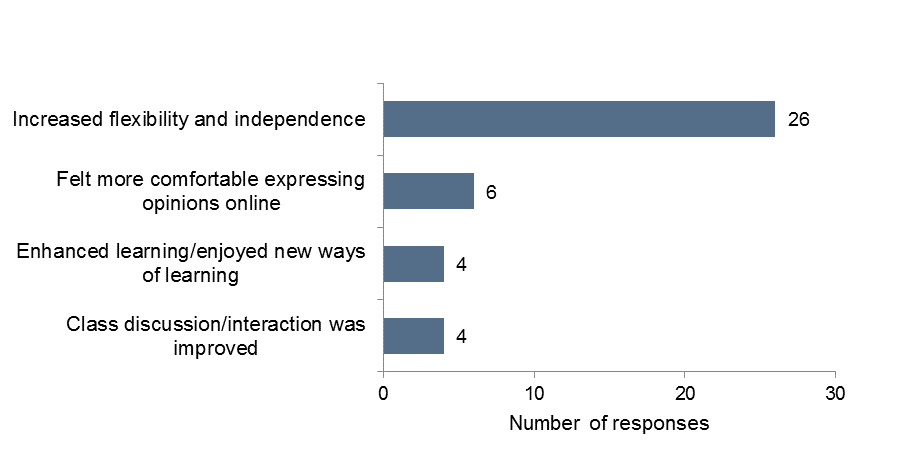

Of students who left a comment explaining why they rated their hybrid/online course as “better” or “much better” than a traditional in-person course, the largest shares cited flexibility and increased independence for their choice (see Figure 26). This was consistent with response patterns from the first course iteration. For example, one student explained:

“I really appreciated being able to effectively go at my own pace instead of being bound by hard scheduling like in a traditional course. There were still deadlines to be kept for accountability, but the course was generally structured to allow for flexibility.”

Another explained:

“I was able to learn the same as if I sat in a regular class, but I was able to customize the learning more to my own schedule and was able to stop a lecture if needed or go back so I could digest it more.”

As discussed above, students also ranked the course as better because they felt more comfortable expressing their opinions in an online format, because the format enhanced their learning, and because class discussion was improved. Three students commented that they felt that they received more feedback in an online or hybrid course than in a face-to-face one, and one student (who was cross-enrolled) even said that she was able to build a stronger relationship with her professor via online communication.

Figure 26: Students’ Reasons for Ranking Online/Hybrid as Better than Face to Face

*Based on coded student comments. Responses could be coded in more than one category.

*Based on coded student comments. Responses could be coded in more than one category.

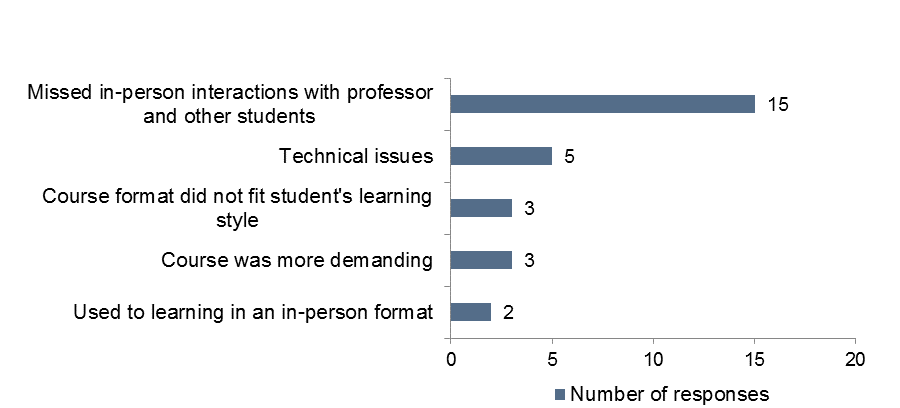

Students who explained why they rated their hybrid or online course as “worse” or “much worse” cited similar reasons as their peers did after the first cycle of courses. Fifteen students missed in-person interactions with their professors and other students, and felt as if something as lost in the online format. Five students cited technical issues as a deterrent, while others explained that the course did not work for their learning style, was more demanding, or just was not what they were accustomed to (see Figure 27).

Figure 27: Students’ Reasons for Ranking Online/Hybrid as Worse than Face to Face

*Based on coded student comments. Responses could be coded in more than one category.

*Based on coded student comments. Responses could be coded in more than one category.

Both instructors and students also indicated that determining whether online or hybrid formats were objectively or measurably more effective than traditional face-to-face courses was a futile endeavor: the two experiences are too varied to be comparable, and context and circumstance play a substantial role. Three students indicated that they preferred in-person courses because it worked better with their personal learning style; while a couple said the same thing about online courses. Other students pointed out that they had a good or bad experience because of course-specific factors like the instructor, course management, or other students in the course, and many felt that the format of the course was secondary amongst these circumstances. Two students said that they missed in-person discussions with other students and their professor, but this was a fair trade-off for increased flexibility and independence, or for the opportunity to take a course not offered at their institution. Three students mentioned that they were commuter students or worked outside of school, so having the opportunity to take a course off-campus and or that they could work around their schedule was a fair trade-off for the loss of face-to-face interactions. It is likely that the substantial shares of students who cited flexibility as a reason for ranking the course highly may have had similar schedule restraints.

Instructors also noted, rather than being “better” or “worse” than face-to-face courses, that the online and hybrid option might be optimal for some students or some circumstances. For example, one instructor commented:

“Online humanities courses are in no way a threat to or substitute for face-to-face courses. Yet for certain students—those needing to grab an extra course to graduate, or who have busy sports schedules or are studying abroad—the online option is wonderful to have. For example, the second iteration of my course was taken mostly by seniors who needed a final historical studies course to graduate.”

Another expressed a similar sentiment, but worried that the format might not be right for many of the students at her institution:

“I am not sure that all students would do well in the online environment. We have many first-gen and minority students. I have not had either demographic in my online class to date. I would hesitate to advise a student about online without knowing a bit about the student. I am a big fan of online learning, but I do think it’s not necessarily THE BEST for everyone. Some students need the F2F contact, some don’t.”

Finally, in a particularly interesting comment, one instructor wondered if we might think of online learning as a sort of competency that few students have had a chance to master. In other words, any of the apparent “shortcomings” of the Consortium courses in terms of learning, interaction, and community may not be inherent in the format, but rather a function of the fact that students (and, arguably, instructors) need more preparation to use the online and hybrid formats effectively.

Overall, these data suggest that, while the online or hybrid format does pose some significant challenges to traditional conceptualization of in-person discussions, these courses can offer rich learning experiences, especially to students who are self-motivated, open to new learning opportunities, or have schedule constraints. In addition, both students and instructors may still have much to learn about how to most effectively use online and hybrid courses to enhance learning and build community.

Goal 3: Increasing Efficiency

The potential for cost efficiencies has been an important consideration and goal of this initiative. Based on our analysis of timesheets and instructor surveys, it appears that any eventual economic benefits will derive from sharing of courses across the Consortium, not from instructor time savings. Our analysis of timesheets from the first course iteration indicated that online and hybrid courses entail additional start-up costs in terms of faculty planning time and support costs, not to mention technology infrastructure. But in the second course iteration, instructors spent considerably less time planning (or revising) and delivering their courses, likely because many of the components for these courses were already in place.

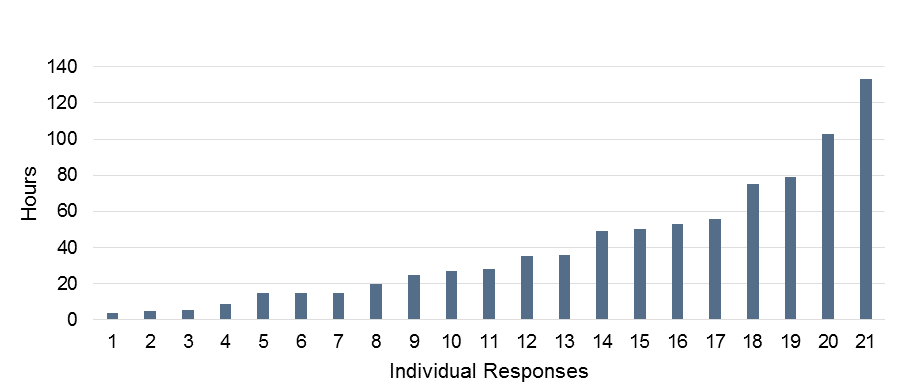

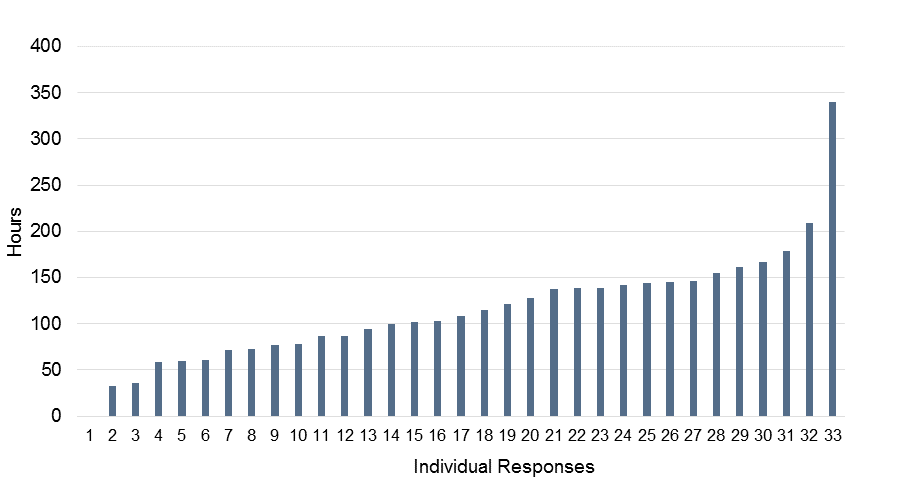

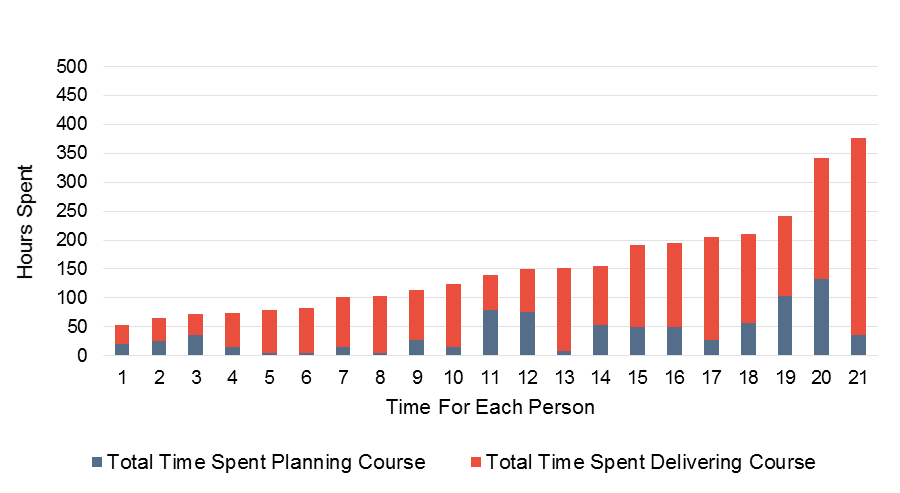

Our analysis of timesheet data indicated that, on average, instructors spent forty hours revising their courses for the second iteration, compared to the sixty-five hours they spent planning their courses in the first iteration (see Table 1). The lion’s share of this time was saved in activities related to creating course content. Instructors also spent, on average, 115 hours delivering their course in the second iteration, compared to roughly 140 hours in the first course iteration (see Table 2). Most of this time was saved by reducing the amount of time spent grading assignments, with some additional time saved in supporting individual students. Time spent on the course did not vary significantly course type, by instructors’ years of experience, or access to training, IT, or instructional designers. While the limitations of timesheet data, which was entered sporadically in some cases, make it hard to affirm the accuracy of these precise numbers, these data, when combined with survey responses from instructors, credibly confirm that instructors spent less time on their course in their second iteration than in their first.

Figure 28: Time Spent Revising Course (Year 2)

Table 1: Year 2 Course Revision Time

| Average (difference from year 1) | Median | 25th Percentile | 75th Percentile | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revision of Course Content | 16.9 hours (-26.7) | 17.4 | 10.0 | 25.9 |

| Start-up Activities | 7.2 hours (-.9) | 2.8 | 1.5 | 10.0 |

| Dealing with Copyright Issues | 1.6 hours (+.2) | 0 | 0 | 1.0 |

| Unusual Administrative Activities | 4.1 (+1.6) | 0 | 0 | 2.0 |

| Administrative Planning for Consortium Scale-Up | 6.6 (+5.7) | 1.0 | 0 | 7.0 |

| Course Planning for Consortium Scale-Up | 3.4 hours (+0.0) | 0 | 0 | 2.0 |

| Total Time Planning | 39.9 hours (-24.9) | 28 | 15.0 | 53.8 |

Figure 29: Time Spent Delivering Course

Table 2: Year 2 Delivery Time

| Average (difference from year 1) | Median | 25th Percentile | 75th Percentile | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Face-to-Face Class Time *14 courses had face-to-face class time | 14.6 (-1.5) | 0 | 0 | 36.75 |

| Supporting Individual Students | 25.4 (-2.5) | 22.0 | 14.25 | 42.63 |

| Grading Assignments | 38.3 hours (-14.2) | 32.0 | 20 | 52.50 |

| Tweaking Course Plan | 19.9 hours (+.4) | 11.0 | 3.75 | 33.25 |

| Other Time on Delivery (including online sessions) | 18.1 hours (-6.5) | 6.0 | 0.0 | 20.38 |

| Total Time Delivering the Course | 115.2 hours (-24.3) | 105.5 | 85.8 | 159.63 |

Figure 30: Total Time Spent on the Course

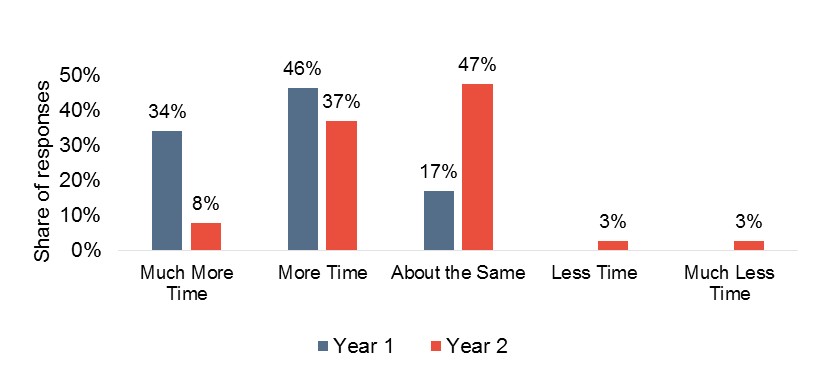

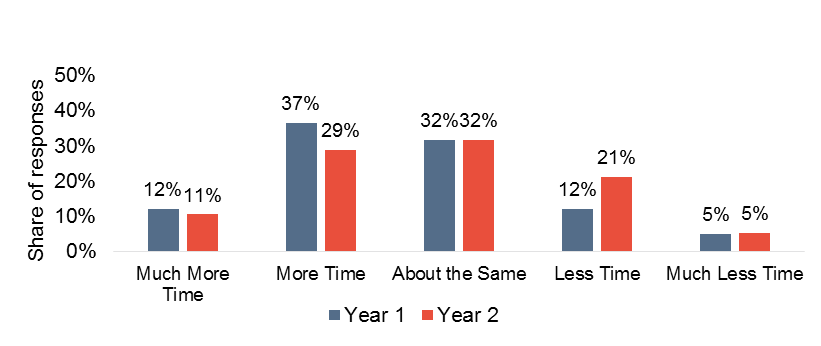

Instructor survey responses were consistent with our findings from the timesheet analysis. While the majority of instructors reported that they spent more time or about the same amount of time preparing for and teaching online courses than they did for face- to-face courses, these shares were slightly smaller than last year (see Figures 31 and 32). Not surprisingly, instructors who reported that they made significant changes to their courses reported spending more time planning and delivering it.

Figure 31: Planning Time vs. Face to Face

Figure 32: Delivery Time vs. Face to Face

After the initial round of courses prepared for the Consortium, several instructors commented that planning their online or hybrid course took significantly more time than planning a face-to-face course. Consistent with the timesheet data, few instructors expressed this sentiment in the second year, and many commented that the process was less time-intensive than in the last year. For example, one instructor explained:

“THE WORKLOAD WAS MUCH MORE MANAGEABLE! In the first iteration of my course I was spending at least 20 hours a week creating lectures, monitoring online discussion boards, etc. This year I was able to devote a much more appropriate amount of time to teaching this course. The big difference for me was being able to re-use my lectures from last year (with only minor modifications).”

Still, evidence from last year, combined with instructor comments, indicates executing an online or hybrid course required more upfront planning and time to create content. Two instructors commented that keeping up with discussion boards to ensure engagement was more burdensome than face-to-face conversation, and three instructors said in their final reflections that careful planning was critical to course success.

At the end of the first iteration of courses, we concluded that substantial increases in efficiency would come not from decreases in instructional time, but through increased course enrollments. Because putting a course online proved unlikely to attract more students within an institution (this was the case in the second iteration as well), we concluded that increased course enrollments would have to come from cross-enrollments. As discussed above, CIC Consortium courses were largely unsuccessful in substantially increasing course enrollments via cross-enrollments in the second year. While this was stifled by some logistical challenges, the bigger barrier was non-participating faculty members’ resistance to promoting or listing Consortium courses.

Despite these challenges, we still maintain optimism that course sharing among small, independent colleges can save money in the long run. If a regular professor is on sabbatical, for example, online courses might be offered instead of hiring additional adjuncts. Or, online courses can be offered to bolster the number of courses available to students without adding to the number of faculty. These costs must be analyzed over time, but online courses seem to be a helpful addition to the small college curriculum.

Overall Assessment

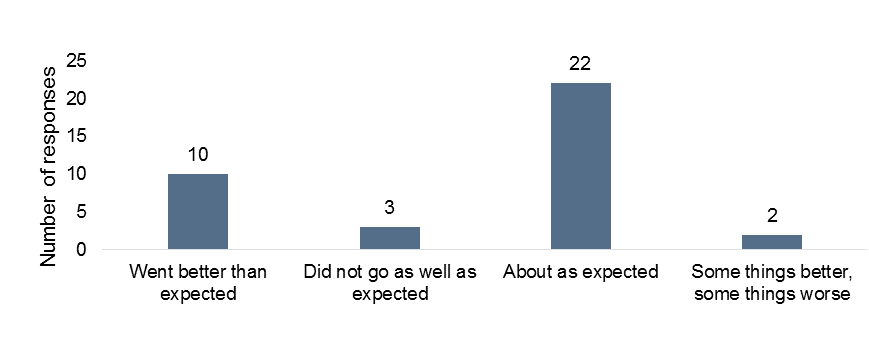

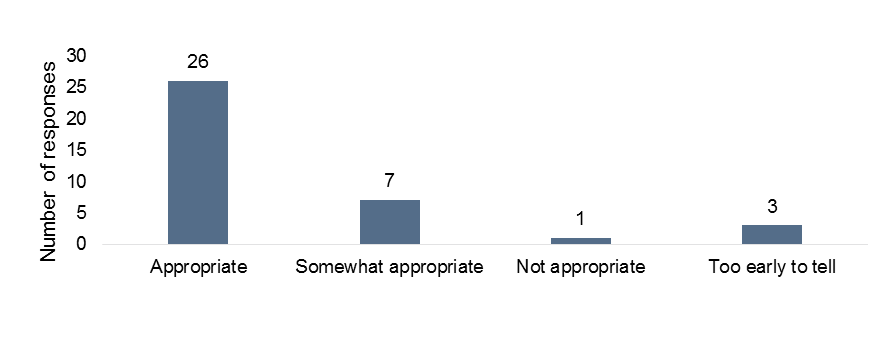

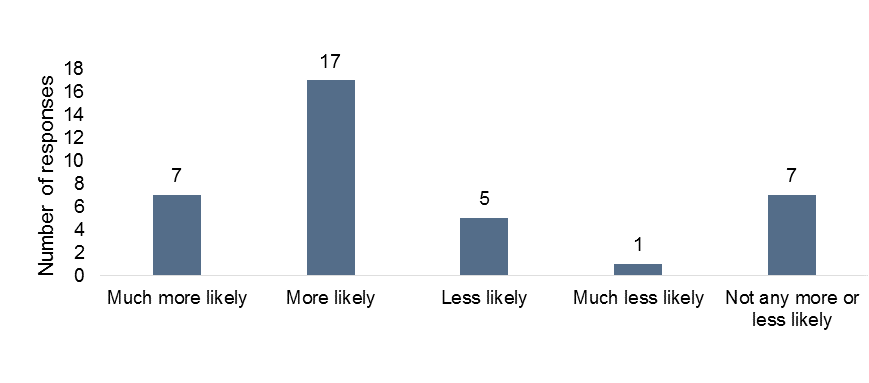

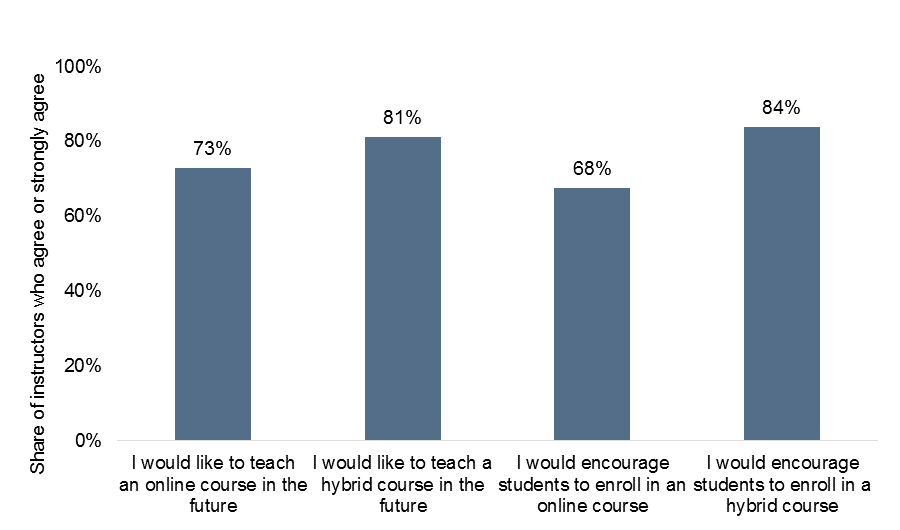

Overall, students, faculty, administrators, and registrars reflected favorably on their experiences with the Consortium. Like last year, most instructors reported that the course went better than or about as well as expected (see Figure 33), and nearly all instructors said that, after their experience, they thought that the online/hybrid format was appropriate or somewhat appropriate for teaching advanced humanities content (see Figure 34). Most agreed that they would like to teach a hybrid or online course in the future (see Figure 35). Twenty-four out of thirty-seven instructors said that they were much more or more likely to encourage colleagues to teach online as a result of this experience, and large majorities agreed that they would encourage students to enroll in an online course or hybrid course (see Figure 36).

Figure 33: Instructor Overall Course Assessment

Figure 34: Instructors’ Ranking of Appropriateness of Online Format for Humanities Courses

Figure 35: Likeliness that Instructor Will Teach Online/Hybrid in Future

Figure 36: Instructor Attitudes Towards Future Involvement in Online Teaching

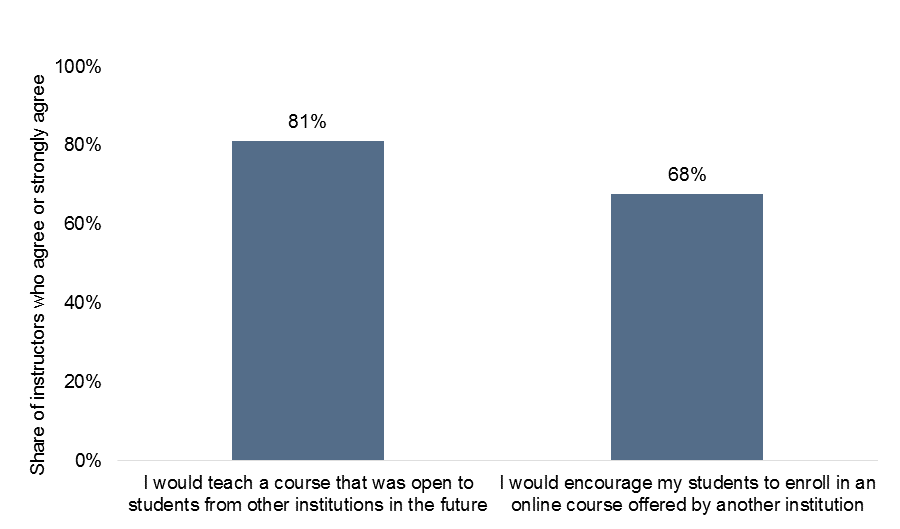

Instructors were also enthusiastic about potential opportunities for cross-enrollment and course sharing: thirty agreed or strongly agreed that they would teach a course that was open to students from other institutions in the future. Fewer, though still a majority (25 instructors), said that they would encourage their students to enroll in an online course offered by another institution (see Figure 37).

Figure 37: Instructor Attitudes Towards Student Involvement in Online Learning

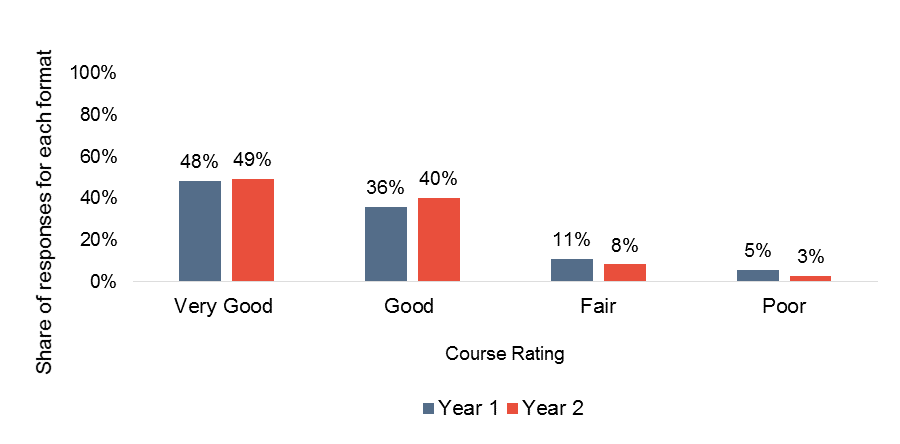

Students also indicated that they had a good experience, with the vast majority rating their course as “very good” or “good” (see Figure 38). This did not vary substantially across course format or among locally enrolled and cross-enrolled students, and students in the second course iteration tended to rank their course similarly to those in the first.

Figure 38: Student Overall Course Ratings by Year

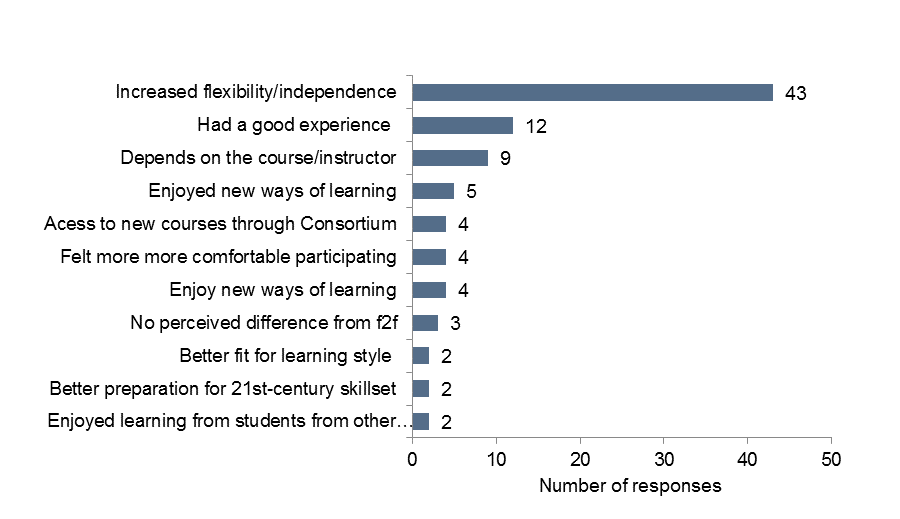

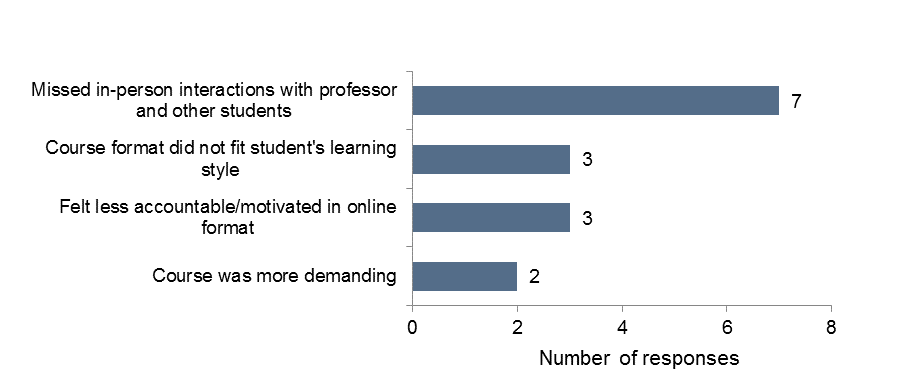

Like instructors, a majority of students (80 percent) said that they would consider taking an online or hybrid course again. Students’ explanations for why they would take a hybrid or online course again echoed many of the sentiments they expressed when asked to compare their Consortium course to a traditional one. Among students who left a comment explaining why they responded “definitely yes” or “probably yes” when asked if they would take another online or hybrid course, forty-three (about 50 percent) cited flexibility and independence as their top reasons. Others commented, more generically, that they had a good experience, that it would depend on the subject or instructor, or that they enjoyed new ways of learning (see Figure 39). Among the twenty-two students who said that responded “no” or “definitely no” when asked if they would take a hybrid or online course again, the largest shares said that they missed in-person interactions (see Figure 40). Both of these patterns resembled the patterns in the first year.

Figure 39: Students’ Reasons for Taking an Online/Hybrid Course Again

*Based on coded student comments. Responses could be coded in more than one category.

*Based on coded student comments. Responses could be coded in more than one category.

Figure 40: Students’ Reasons for Not Taking an Online/Hybrid Course Again

*Based on coded student comments. Responses could be coded in more than one category.

*Based on coded student comments. Responses could be coded in more than one category.

Though instructors sometimes expressed divergent opinions when it came to which tools and techniques worked best, and many lamented a loss of personal connection with their students, a substantial number felt that teaching an online or hybrid course through the consortium was a great learning experience. Four explicitly said that the experience helped them rethink their pedagogy and learn about new tools and techniques, For example, one instructor commented:

“This was a very good teaching/learning experience for me. It confirmed my belief that engaging online course are indeed possible. Developing and teaching the course gave me the opportunity to try different types of online collaborative role playing activities. I am appreciative of the opportunity to be involved with and contribute to this pilot project.”

Another explained:

“I don’t know the results of this project in terms of cross-enrollments, but I think it was an excellent initiative, one that sparked new ideas and creative thinking at our institution. I think the positive outcomes may be more long term and equally “localized” for other participants. I hope that this impact will come out at the final national meeting, if they don’t in the results of this survey.”

And another:

“Despite the frustrations, I am very grateful to the CIC for securing this opportunity for teaching humanities courses online. For me, it has raised more questions than answers – especially regarding what ‘teaching’ and ‘learning’ actually are, and what conditions are necessary for them to ‘happen.’”

These comments indicate a crucial outcome of the Consortium, and one that is only partially included in the initiative’s goals: participation in the Consortium helped instructors improve their teaching, in both online and face-to-face settings, and created conditions for innovation and creativity to spread within participating institutions. Time and time again, instructors commented on how much they had learned from the experience, or referenced specific tools or techniques that they would incorporate into all of their classes. Other times, we heard that participating instructors were successful in interesting their non-participating colleagues in online teaching, or, at the very least, in new tools and teaching techniques. While our data shows that participation in the Consortium increased instructors’ and institutions’ capacity to offer online and hybrid courses, there is also significant evidence that the initiative may have an impact on residential courses at these institutions as well.

Conclusion

Our conclusion after the second course iteration is that online humanities courses can provide rich learning experiences for students at liberal arts colleges and universities, especially for students who are self-motivated, would benefit from flexibility and independence, or who wish to take a course not offered at their home institution. Though it is hard (and perhaps misguided) to compare online or hybrid learning experiences to traditional in-person ones, students in Consortium courses performed well on course grades and learning outcomes, and most courses were successful in fostering community, dialogue, and engagement. Furthermore, there seems to be a learning curve in terms of instructional efficacy and efficiency in the online format: most instructors felt that their courses were more successful in their second iteration, and nearly all used less time to plan and deliver their courses. We anticipate that other opportunities for cost-sharing will come from increased success in incentivizing cross-enrollment so that courses can truly be shared amongst institutions.