Emergent Data Community Spotlight II

An Interview with Felicity Tayler and Marjorie Mitchell on the SpokenWeb Project

For all today’s technological affordances, research data sharing remains a fundamentally social activity, dependent on building “data communities” from the ground up. Danielle Cooper and I argued as much in a recent issue brief, and since then, I’ve been seeking out pioneers who are at the forefront of efforts to grow emergent data communities in a variety of research areas. What does it take to get a successful data sharing movement off the ground, and what strategic supports are needed for the future?

In July, I interviewed Vance Lemmon about the movement to facilitate data sharing in spinal cord injury research. In this blog post, I turn to a very different research area – the digital humanities. I’m delighted to introduce Felicity Tayler, Research Data Management Librarian at the University of Ottawa, and Marjorie Mitchell, Research Services Librarian at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan Campus. Felicity and Marjorie are co-investigators and research data management advisors for a research partnership entitled “The SpokenWeb: Conceiving and Creating a Nationally Networked Archive of Literary Recordings for Research and Teaching.” Since the introduction of sound recording technologies in the last decade of the nineteenth-century, and especially since the 1950s with the introduction of portable tape recording, writers and artists have documented their performances of literary works, events, and conversations with creative abandon. The SpokenWeb partnership aims to identify, preserve, and render this extensive body of valuable cultural heritage material available and useful for research, teaching, artistic transformation, and widespread enjoyment.

I talked with Felicity and Marjorie about what it means to work with “data” in the humanities; the significance of community – both within and outside academia – for their project; and the importance of collaboration between scholars and information professionals.

- I imagine most people wouldn’t automatically think of literary sound recordings as “data.” Could you describe the data you’re working with at SpokenWeb – what it represents, how it’s stored, and how it’s accessed?

It is commonly held that defining “data” in the digital humanities is a slippery task because there are many conflicting definitions of data. As Miriam Posner has observed of humanists, “We can know something to be true without being able to point to a dataset…. In fact, very few traditional humanists would call their source material ‘data.’” As co-investigators and research data management advisors on the SpokenWeb partnership, we run a workshop that helps individual researchers identify the data, or file types, that their localized site produces and which they will rely upon for critical analysis. We then emphasize a shared metadata schema and file naming conventions as a common language, and as an expression of community, across the research partnership.

Many different kinds of “data” are produced across multiple sites in this process of preservation, digitization, and publication of literary audio recordings. Audio files include masters and processed masters files (.wav) and processed access copies (.mp3), but there are also administrative forms that have to be tracked such as waivers and consent forms (.doc, .pdf); there are image files that document the physical media as historical artifacts (.jpg); and there are spreadsheets and xml encoded transcriptions (.xlxs, .doc, .txt) that have to be associated with the audio files and their administration. Another layer of file types includes those produced by the individual researchers as they engage in data analysis and visualization, create code and pedagogical tools in applications such as Jupyter Notebook, or remix content in creative projects.

- How are these sound recordings used, in research and otherwise?

The first year of our partnership concluded with the SpokenWeb Sound Institute, a two-day event where the project Task Forces met up, and co-investigators and students shared tools and methods. This was an opportunity to get a sense of the different approaches that the partnership was taking towards using sound recordings as research data, and how shared infrastructure such as metadata schemas, data repositories, rights management, and ethics protocols might enable this research across geographically dispersed collections.

Karis Shearer (UBC Okanagan) is developing protocols and pedagogical resources for turning analog recordings into digital data. Tanya Clement (Texas A&M), Liz Fischer (Texas A&M), Brian McFee (NYU Steinhardt), Marit MacArthur (UC Davis) and Lee M. Miller (UC Davis) work with computational methods for audio signal analysis and visualizing audio data. In this way patterns of silence and non-silence, vocal or non-vocal frequencies, speaker segmentation, pitch and timing patterns can be detected. Such measures can be useful entry points to the work of Jason Camlot (Concordia University) to outline methodologies for the study of spoken recordings as literary artifacts, defining core critical concepts such as “literary recording,” “sound,” “signal,” “audiotextual genre,” and “sound media formats,” and then move into a more focused discussion of what “the literary” sounded like during the specific historical periods as sound recording technology has developed. Jonathan Dick (MA student, University of Toronto) analyzes the audio data for patterns of racialized voice; Jacob Knudsen (BA Student First Nations Studies) is developing decolonizing methodologies for working with sound recordings from the Red Power movement; Ali Barillo (MA Student, University of Alberta) is studying the behavioral patterns and communicative function of applause at live events.

The idea is that this analysis through computational methods will give greater context to the literary genres represented in the recordings, how and when it was written and recorded, some of the circumstances surrounding the writing of particular poems or books, and intersections with the recording technologies available at the time. This allows for fuller, deeper research into the works themselves as well as the creative communities surrounding their production and reception. When permissions allow, the audio recordings are sometimes remixed into new creative pieces.

- What does “community” mean in relation to the SpokenWeb project?

The SpokenWeb partnership is interested in the expression of community, as it can be detected in audio recordings. Currently our research team is headed by Jason Camlot at Concordia University, with 34 co-investigators, 11 collaborators, and 28 students from universities across Canada and the United States, as well as three Montreal-based community partners, to begin with. Many of our academic partners also have strong relationships to localized creative communities. We think about these roles and relationships in historical, contemporary, and future terms. Digitizing archival audio material reminds us of creators and their listening audiences of the past, including the listeners who would have been brought together at live events, and after the events, when listening to the recordings.

In the present, to further consolidate community within the research team, we build shared data infrastructure (such as “Swallow,” our metadata cataloging tool, and the documentation for our common metadata schema). We also actively plan repository and data sharing infrastructure with future users in mind, as we try to negotiate licensing and other permissions that will make the recordings and their metadata available to wider publics alongside pedagogical tools and contextualizing resources. While we work with archival material in institutional collections, we also program real-world events to foster future communities of reception, interpretation, and curation. Further, an important part of the SpokenWeb mandate involves engagement with literary and cultural communities across Canada to assist in the preservation and development of AV materials they may have produced over the years in documenting their own, local literary and arts events. We are presently working with two community partners, Wired on Words and Archive Montreal, to collaborate on the digitization, description, and development of spoken word collections, and on making these materials available to the communities they document in meaningful ways. This work will expand to other literary communities that hold such collections and wish to develop them.

All of this said, the archival collections and resulting datasets that we work with are not comprehensive. As in all forms of community building, there are boundaries of inclusion and exclusion. The SpokenWeb community is built through relationships largely forged between faculty, librarians, existing institutional collections. We are attentive to the gaps that are produced through these methods and have several members actively forging relationships outside of academia that will address the inequities of institutional collections (and the bias of our datasets).

- What unique challenges or barriers are there to achieving widespread sharing and use of sound recordings as data?

Many layers of challenges exist in sharing historical sound recordings, and they have become part of the SpokenWeb research program.

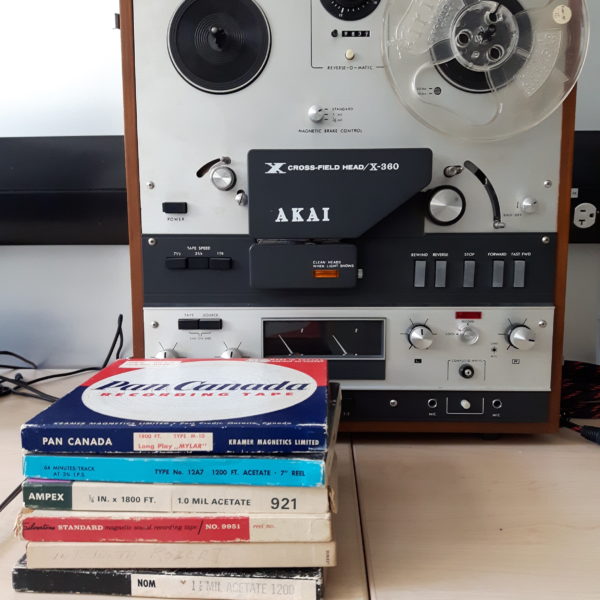

Accurately describing the physical recording media and the digitized recordings is a challenge as the contents of the tape don’t always match what is listed on the box. Preservation of the magnetic tapes, both reel-to-reel and cassette tapes, is an issue in the digitization process. The machines used to play magnetic tape are obsolete and hard to locate. Each time the tapes are played, they are one step closer to the end of their useful life. Some of the analysis of the contents requires repeated playback and without digitizing the contents, would be almost impossible. Once digitized, should we clean the audio? Also, how many copies of these recordings can/should we be keeping? And where? How should we encourage the adoption of common storage and sharing infrastructure across 21 institutions, not all of them academic?

The copyright of the recordings is not straightforward. None of the works are old enough to have entered the public domain. Negotiating the permissions for sharing or terms of licensing is complex, as digital file sharing platforms did not exist when most of these recordings were made. Existing agreements signed with the archives where recordings are housed often do not address usages beyond individual research. We are negotiating the limits of what can be shared within the research partnership, once digitized, and what could and should be shared with a wider non-academic audience.

- What are the most important supports researchers need in order to cultivate a thriving data community around literary sound recordings?

This is another area where SpokenWeb has taken up this question as part of its research methods. From the outset, a condition for faculty joining the partnership was that they would team up with a librarian collaborator. This ensures institutional support for working with special collections material, but also leverages an existing network of practitioners already engaged in building common infrastructure for research data management on a national scale. The annual gathering of project partners through the Sound Institute and Symposium gives a real-life dimension to the sharing that takes place on digital platforms. A steady stream of live events such as poetry readings, performances, workshops, and exhibitions provide opportunities for the historical recordings to be interpreted in the present moment.

These real-world community building opportunities will have to be paralleled with research data infrastructure – but we don’t know what that looks like yet. At the time the tapes were created there was a robust culture of passing these tapes from one person to another within the literary community of a city, region, or country. Providing access to these digitized recordings for researchers and to wider publics will be a crucial support for a future thriving transnational and transdisciplinary data community brought together around literary sound recordings. A web interface that manages access levels to data files, citation of datasets, and assigns DOIs is important – but so is a highly customizable interface, and the ability to stream video and audio files without download. Data repository platforms are out there, but we haven’t found a match yet.

- Do you consider SpokenWeb a digital humanities project? How do you see this emergent data community relating to wider research trends?

We think this is one of the largest funded digital humanities projects in Canada right now. It is setting an example in the field in terms of project management for interdisciplinary partnerships and in negotiating conditions of student (research assistant) labor across multiple institutions. Beyond this, wider research trends include audio signal analysis, data visualization, and linked open data models for cultural resources.

- You’ve touched on this a bit already, but what role does digitization play in the SpokenWeb project?

Digitization of SpokenWeb-affiliated collections is pursued in a variety of ways. When absolutely necessary we may outsource digitization of some assets to reliable vendors such as Media Preserve. But several of our partner institutions have strong in-house capacities for digitization, and that’s a great advantage to us. For example, the University of Calgary has developed digitization infrastructure for the processing of its very large EMI Canada collection, and we have benefited from their advice and expertise on how to approach digitization for our spoken word collections. The University of Alberta also has equipment and expertise for the digitization of the collections we’re working with. Karis Shearer at the University of British Columbia has been developing video tutorials on the basics of digitization processes for use across the SpokenWeb research network. Jason Camlot has recently been awarded a Canadian Fund for Innovation (CFI) grant to build the AMPLab (Audio Media Poetics Lab) at Concordia University, which will include stations designed specifically for the digitization of archival collections of documentary sound recordings produced in a variety of analog media formats, ranging from audio reel to reel and cassette tape, to MiniDisc, Umatic Video, etc.

Establishing a lab that allows our program to engage with the legacy media technologies that produced the artifacts we are studying allows us to take digitization as a process out of the black box it often seems to be hidden in, and to think about the migration of signals from analog to digital media formats as part of larger, interesting questions we have about the relationship between media technologies and formats, and literary forms and production. In our project, digitization isn’t just something that ‘happens’ to our collections, but, again, becomes a research question for us to explore. At the same time, having in-house capacity for digitization will also allow us to coordinate digitization across partnering institutions and communities (including archives and local literary event organizers) that may not otherwise have access to the necessary equipment.

- What would you say has been the greatest success of the emergent literary sound recording community so far?

From our perspective as research data management librarians, we are proud of the common metadata schema developed by the Metadata Task Force and its uptake by every partner that is cataloging audio recordings. We are excited by the potential of Swallow – the custom built platform to hold this metadata – as it will be the backbone for future data sharing across the partnership. We are also keen on a workshop that we’ve built to help our partners to discover and map their data flow as a step towards growing the community they are building.

- What’s on the horizon for data sharing in literary sound studies?

Greater access to these digitized audio recordings regardless of location. This access is going to be dependent on our ability to coordinate research data management infrastructure choices across institutions. Once we work out permissions on a case-by-case basis with the archives that hold the analog recordings, we can also extend this community of data sharing in sound studies beyond the boundaries of the research team.

Interested in developing or improving research data services on your campus? Ithaka S+R is embarking on a collaborative research project on Supporting Big Data Research. Participants will work alongside Ithaka S+R conduct a deep dive into their faculty’s needs and craft evidence-based recommendations. To find out more about having your library participate as a research site for this project or future projects, please email danielle.cooper@ithaka.org.

Pingbacks

The Research Data Sharing Business Landscape - The Scholarly Kitchen