Forgive and Forget? Understanding the Impact of State-Funded Student Loan Forgiveness Programs

While student loan forgiveness is trending at the federal level, little attention has been directed towards learning from state approaches or the impact that federal forgiveness could have on state policy and practice. While not all states have programs, some have loan forgiveness options that pre-date the main federal program, Public Service Loan Forgiveness, or PSLF. Twenty states operated state-funded student loan forgiveness programs in 2020, spending over $65 million to forgive or partially repay students’ loans.

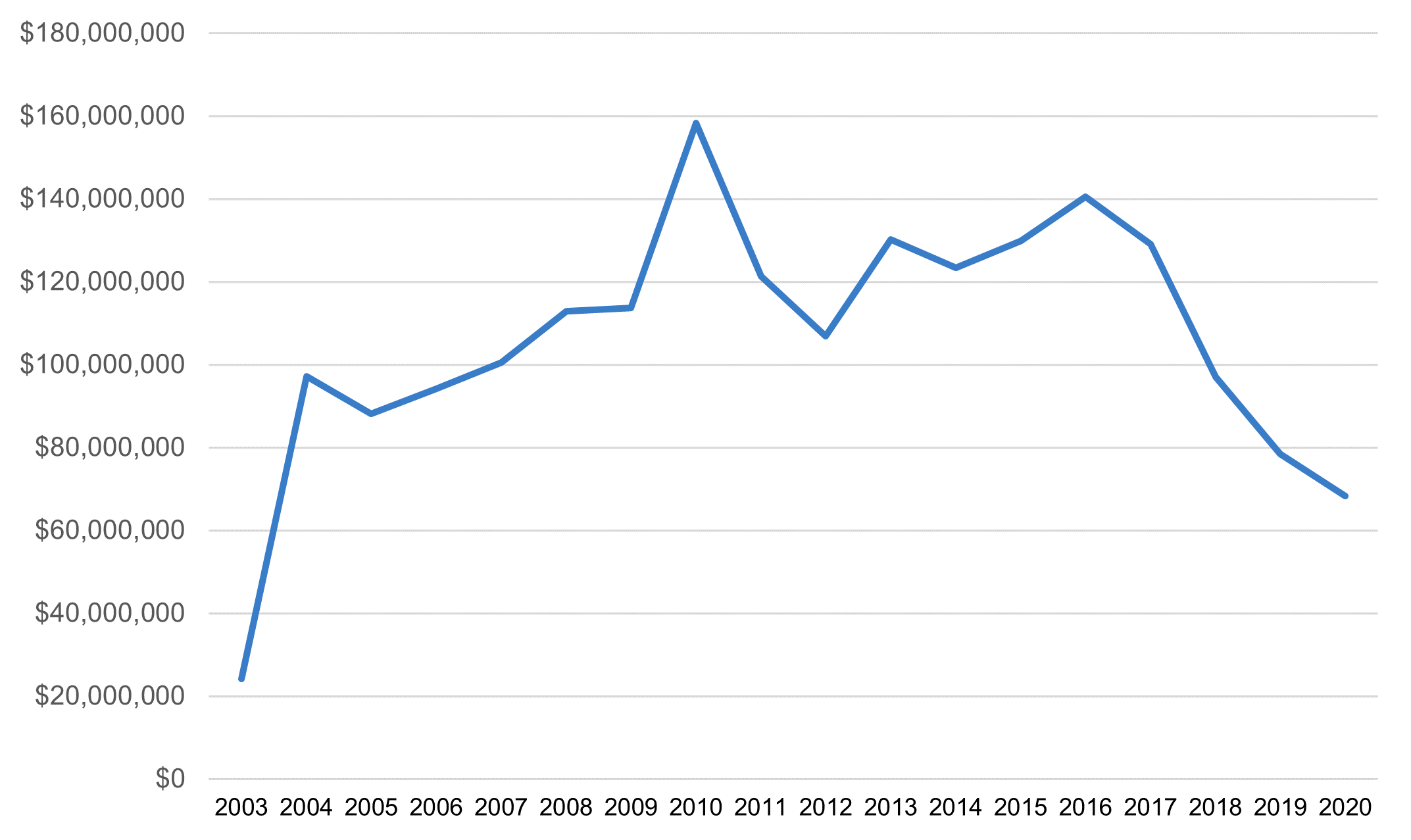

According to a survey from the National Association of State Student Grant and Aid Programs (NASSGAP), over time, states have spent less on student loan forgiveness programs every year since 2016—decreasing from a peak of about $140 million. The programs also serve relatively few students—states reported under 9,000 students receiving state-funded loan forgiveness in the entire country in 2020.

Figure 1: State spending on loan forgiveness programs, 2003-2020

Source: NASSGAP. Figures are shown in constant 2021 dollars.

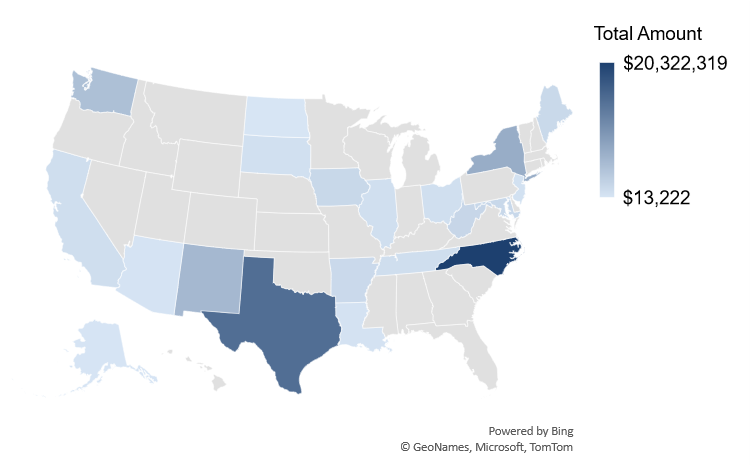

However, a minority of states seem to remain committed to loan forgiveness as a policy strategy. Figure 2 below illustrates the total amount each state reported in loan forgiveness programs in 2020. There is also an efficiency question embedded within the data. For example, North Carolina spends the most of any state on loan forgiveness over two different state programs. New Mexico spends a quarter of what North Carolina does over 11 unique programs.

Figure 2: State spending on loan forgiveness programs in 2020

Source: NASSGAP

State loan forgiveness programs generally work in one of two ways: states lend students their own dollars, which are then eligible for forgiveness, or, states forgive student loans originally lent by other entities. For example, in North Carolina, the Forgivable Education Loans for Service program gives students an opportunity to apply for student loans from the state that are forgivable if they work in a high-need area. In this scenario, the state lends and forgives their own dollars when students meet the requirements. If a student’s plans change, they must repay the loan to the state. In contrast, the Texas Physician Education Loan Repayment Program will repay loans held by other entities after students complete the service requirements. The amount may or may not be enough to repay the loan in full.

Broadly, there is limited research that critically examines state-funded loan forgiveness programs. While some students do receive forgiveness, we generally do not know if or how the forgiveness program figured into their decision making about postsecondary education, their selected field, or where they live. A 2016 literature review on programs focused on teachers found descriptive and correlational evidence that the programs may be effective, as did a 2000 review of state programs for medical professionals. However, neither study demonstrates any causal link between the state’s loan forgiveness incentives and borrower decision making.

If President Biden and/or Congress move forward to forgive all or part of students’ federal loan balances, some state programs will likely be impacted. If a student holds a state-funded forgivable loan, they will still be liable for that loan regardless of which forgiveness plan is enacted. However, if the student was planning to use a state-funded forgiveness program for their federal student loan, the incentive to complete the state’s forgiveness requirements could disappear. While this would save states money, very little is known about the impact it could have on states’ workforces in high-need professions and geographic areas. Therefore, from a state perspective, broad-based federal student loan forgiveness could have the potential to dull one tool in states’ workforce development toolbox—albeit a relatively limited one.