Finding the Public Domain: The Copyright Review Management System

The public domain is the ultimate open access. It is key to the bargain of copyright. Rather simplistically, in order to incentivize authors to produce works, the public, through Congress, grants authors copyrights in those works. While there is a range of opinion about the purpose and nature of copyright, they all have one common idea: copyright is limited by time. A copyright is a monopoly that lasts for a limited time and is limited by certain conditions. Those limitations on these otherwise exclusive rights include fair use and first sale along with a host of specific exceptions and restraints to copyright. Most readers will be familiar with the language of Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution which empowers Congress “To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.” This duration limit is a Constitutional requirement. It means that copyrights evaporate entirely after a certain point in time.

We say, then, at that point in time that the work is in the public domain. And the public domain is the ultimate open access.

Under this theory of copyright, that entry into the public domain fulfills the bargain of copyright. Unfortunately, determining whether an item has entered the public domain requires legal expertise and time-consuming research. Even then, research can be inconclusive and the legal details can be murky. The facts required to make the legal analysis are difficult to ascertain in many cases. As a result, libraries and librarians remain uncertain about the copyright status of many items on our shelves, and we often treat public domain works as if they are protected by copyright. This uncertainty is a source of near-universal frustration. It extends well beyond libraries and our fellow memory institutions, affecting authors, rights holders, and the public at large.

Historically, copyright review has been uncoordinated and has taken place on a modest scale.

Historically, copyright review has been uncoordinated and has taken place on a modest scale. The Copyright Review Management System (CRMS) changes that. [1] CRMS was supported by the Institute of Museum and Library Services over three National Leadership Grants. It was led by the University of Michigan in collaboration with 19 other highly dedicated research libraries. Together, we developed a system to train and coordinate reviewers to assess the copyright status of digitized books held in the HathiTrust Digital Library. Over the course of the three interrelated grants that make up the CRMS project, we developed expertise in managing a large collaborative project.

The project team documented these lessons in a book called Finding the Public Domain: Copyright Review Management System Toolkit.[2] The Toolkit shares practical insights gained in this effort in the hope of supporting others interested in copyright review. This brief complements the practical toolkit. It explains the history of CRMS and introduces the basics of the CRMS procedure. It then discusses some of the lessons, successes, surprises, and challenges of the work.

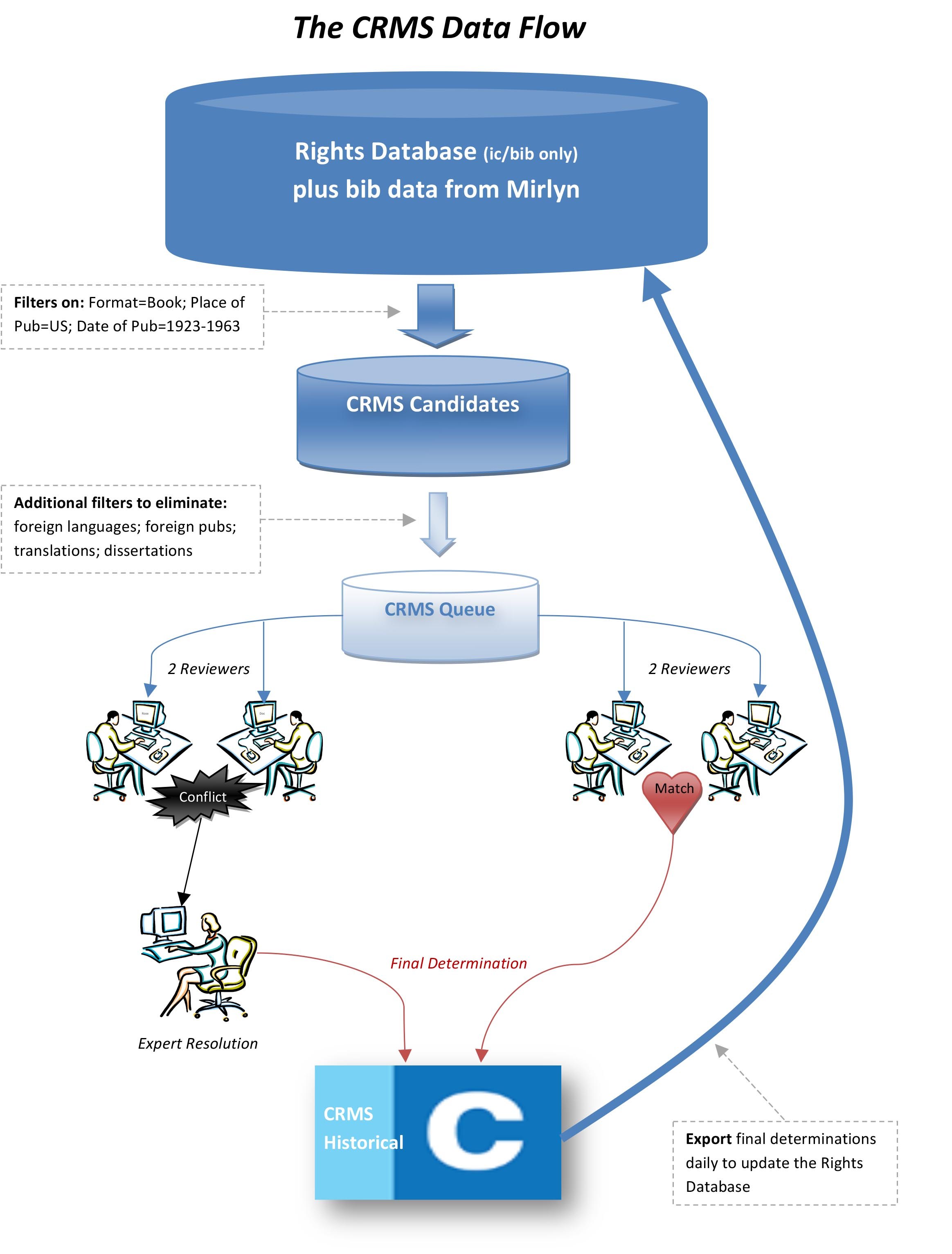

Figure 1.

One of the wonderful surprises was that the American Library Association recognized the project earlier this year when CRMS received the L. Ray Patterson Copyright Award.[3] The award, named for eminent copyright scholar L. Ray Patterson, “recognizes contributions of an individual or group that pursues and supports the Constitutional purpose of the US Copyright Law, fair use and the public domain.”[4] This is the first time that a group has received the Patterson Award.

The History of CRMS

In order to consider the impact of CRMS, some background is helpful. In 2008, a group of university libraries founded HathiTrust to preserve and provide access to their rapidly growing digital collections. Today, there are over 100 HathiTrust partners, and HathiTrust provides full-text search of its collection to all users—14.5 million volumes both in-copyright and public domain as of June 2016 and growing. In addition, it provides full-text access to public domain volumes and provides qualified individuals with print disabilities full-text access to all volumes.[5]

Table 1: HathiTrust by the Numbers[6]

| Total volumes | 14,558,819 |

|---|---|

| Book titles | 7,296,116 |

| Serial titles | 398,912 |

| Pages | 5,095,586,650 |

| Terabytes | 653 |

| Miles | 172 |

| Tons | 11,829 |

| Volumes in public domain | 5,589,014 (~38% of total) |

In the early days of HathiTrust, executive director John Wilkin, now Dean of Libraries and University Librarian at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, described the problem of bibliographic indeterminacy: “the dearth of reliable bibliographical information” about books in research and academic library collections. A major piece of that indeterminacy concerned copyright status. Which volumes were in the public domain and which were protected by copyright?[7]

To address that problem, the CRMS team, led by the University of Michigan Library, developed legal analyses and corresponding decision trees, training materials, and a web-based fact-finding interface. Taken together, these tools enable many individuals and institutions to collaborate in producing accurate copyright determinations. When they determine that a work is in the public domain, it is made accessible in HathiTrust.

The University of Michigan hosts CRMS, but its success was the result of the commitment and dedicated effort of our community of partner institutions.[8] In the first grant (CRMS-US, 2008-11), the University of Michigan worked with Indiana University, University of Wisconsin-Madison, and University of Minnesota. We reviewed over 170,000 HathiTrust volumes that were published in the United States between 1923 and 1963. The team identified nearly 87,000 volumes as being in the public domain. It also gathered information regarding works in copyright.

Table 2: Cumulative CRMS copyright determinations exported to HathiTrust Rights Database (United States)[9]

| Volumes in the public domain | 177,150 (53.6%) |

|---|---|

| Volumes in copyright | 54,884 (16.6%) |

| Undetermined/need further investigation | 98,335 (29.8%) |

During the second grant (CRMS-World, 2011-14), we built on that accomplishment by reviewing an additional 110,000 US volumes and expanded the scope of the review to include 170,000 English-language volumes published in Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia between 1872 and 1944. The original three partners continued their work, and 14 more institutions joined the effort. This second grant included a process for quality control, initial development on an interface for works from Spain, and an expanded suite of materials to allow an expert member of our project team to train and monitor reviewers online. We also added an advisory board of copyright experts that has provided crucial guidance and feedback to the project team since 2012.[10]

Table 3: Cumulative CRMS copyright determinations exported to HathiTrust Rights Database (Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom)[11]

| Volumes in the public domain | 143,570 (79.3%) |

|---|---|

| Volumes in copyright | 17,969 (9.9%) |

| Undetermined/need further investigation | 19,449 (10.7%) |

| Total determinations | 180,988 |

The final CRMS grant (2014-16) simultaneously made possible continued copyright review of CRMS-World volumes, the development of the Toolkit, and planning related to the long-term sustainability of CRMS. Looking forward, CRMS work will be managed under the auspices of HathiTrust with continued administrative, technical, legal, and policy support from the University of Michigan with other partners. With grant funding winding down, we are discussing sustainable approaches for this important work, knowing that it will evolve over time. In the coming months, copyright determination work will continue on US books published from 1923 to 1963. This area is of particular interest to HathiTrust partners as the body of books from that period continues to grow within the HathiTrust holdings. Fifteen HathiTrust partners have already committed staff time to work on reviews going forward into 2017 beyond grant funded work. The willingness to continue review work beyond any contractual or grant commitment evidences the importance of this work for the library community and, in turn, the public.

How CRMS Works

CRMS relies on the distributed efforts of over 60 reviewers, geographically separate but working in close coordination. In order to provide HathiTrust and the University of Michigan with accurate and reliable results, we designed an auditable, documented review process. We began by defining the scope of work. Copyright research can easily become mired in complexity. A practical scope of inquiry should limit the work to a language familiar to the reviewers, one country of publication (or possibly a few countries that have similar legal regimes), and a limited time span. Projects that have more than one country of publication origin or include works with more than one contributor (such as serials and conference proceedings) are more difficult.

During our planning, we built into the system an expectation that many books would be set aside because of complications and uncertainty. The ability to set aside complex cases is important for legal accuracy and functions as a sort of release valve. In asking reviewers to put aside items that present a complex set of facts, we made a cost/benefit decision; the cost of reviewers spending large amounts of time on a single item was not worth the benefit in this project.[12]

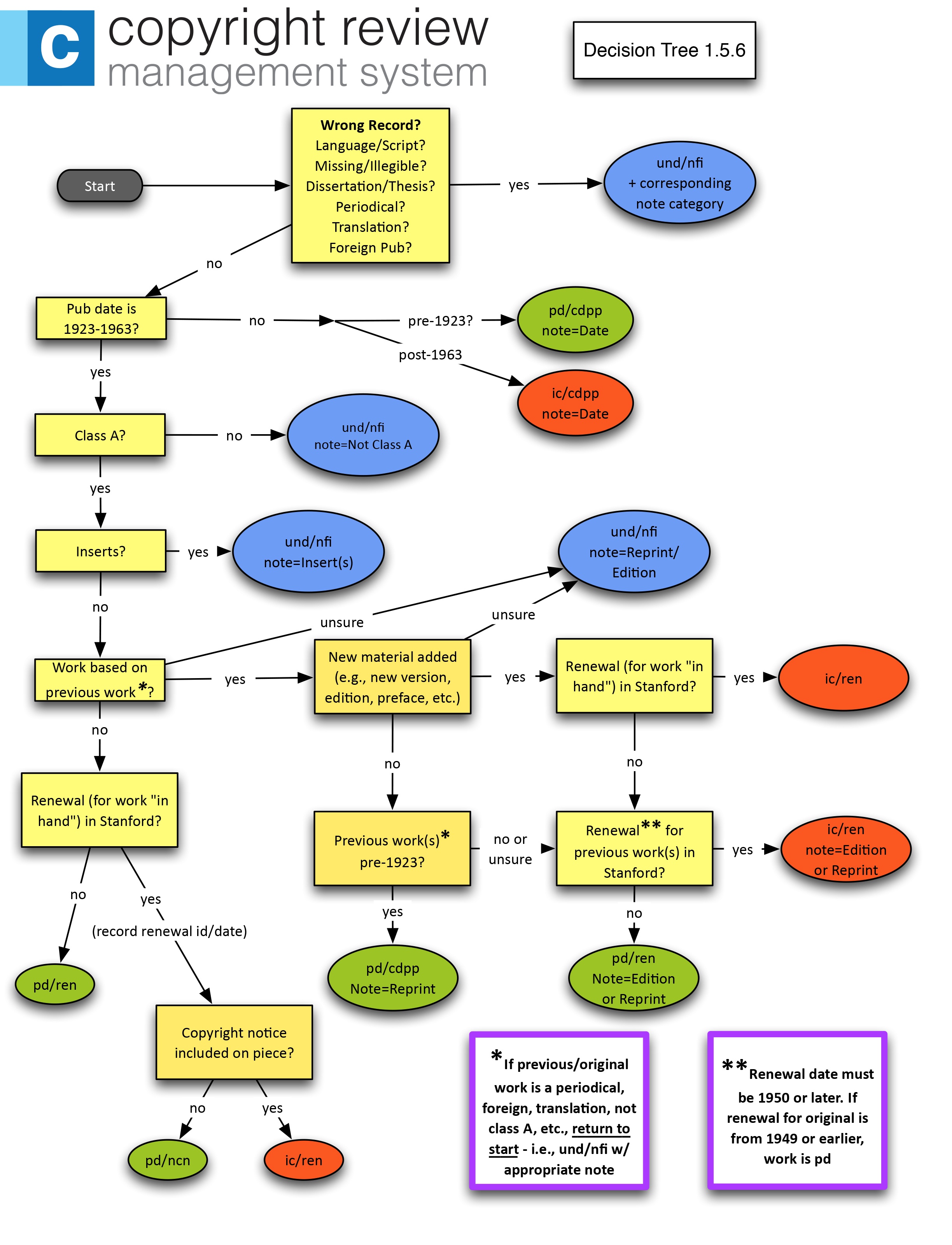

To help step reviewers through the review process, we designed decision trees and robust training protocols (included below). Reducing this copyright research to a series of factual inquiries ensures consistent results. CRMS training emphasizes the importance of following the decision trees closely. Following the order of operation in the decision tree is critical for consistent results.[13]

To start each CRMS project, the team queried the HathiTrust Rights Database to create two pools of candidates, including over 300,000 volumes for CRMS-US and over 170,000 volumes for CRMS-World. Two independent reviewers then researched each of the volumes in the candidate pool. Using two reviewers per volume helps mitigate mistakes and ensure the accuracy of our final determinations. Each reviewer confirms that the scan under review matches its catalog record, examines the scan’s front matter and other relevant content, consults resources for publication dates or author death dates, and then renders a judgment.

If the two reviewers disagree on the rights status of a work, or if they agree on the rights status but disagree on the reason for it, their judgments are passed along to an expert reviewer who renders a final determination on that volume. If the two reviewers agree, or if an expert has decided between them, the system exports the determination from CRMS to HathiTrust that evening. As part of the overnight processing, the determination on that particular volume will be inherited by any other copies of that volume in the libraries that belong to HathiTrust. That shared determination will then be recommended to the HathiTrust Rights Database so the volume’s record can be updated.

Practical Insights from CRMS

CRMS is not only a legal project; it is also a process project.

In total, over the course of all three grants, CRMS performed 330,369 copyright determinations for US-published books and an additional 180,988 determinations for books published in Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom. This is a profound accomplishment, but it is only part of the story. As I was speaking on a panel at a Digital Library Federation meeting in October 2014,[14] I realized what may be obvious to others: CRMS is not only a legal project; it is also a process project. I hope that sharing the following procedural insights will be helpful to colleagues undertaking similar work. Some are hunches that turned out to be true—others we picked up along the way.

Impact

In CRMS, as with HathiTrust, we tend to talk in terms of numbers and scale: millions of books, thousands of copyright determinations, tens of libraries and reviewers, and so forth. But the specific impact of the project is hard to measure because individual users of books opened as the result of a CRMS public domain determination are not aware that their access is the result of the review work. There is no way for a given user to know that any particular book was reviewed by CRMS. (The contrary is also important; that many books remain closed as the result of an affirmative determination that a given book is subject to copyright.) Thus, we do not have specific anecdotes as to how CRMS affected specific research.

That said, it was not uncommon to see a CRMS-reviewed book on the list of top downloads for HathiTrust in any given month. In November of 2013 we compared a list of the top 1,000 downloads from HathiTrust against the list of items that had been reviewed by CRMS at that time. About 12% of the top 1,000 downloads were titles identified as public domain as the result of the CRMS review process. At that time, approximately 3,482,108 works were identified as in the public domain—the combined result of CRMS and bibliographic determinations. While not hard data, this query indicates some significant impact even if it is coincidental. Some of the eclectic books opened in that sample as the result of CRMS work included the Roster of the Confederate soldiers of Georgia, 1861-1865; Quicksand, a novel by Nella Larsen published in 1928; the 1948 US Office of Strategic Service’s Assessment of Men: Selection of Personnel for the Office of Strategic Services; and Coffee Processing Technology of 1963. Strikingly, in light of recent destruction of the ruins at Palmyra, one of the books documents excavations there in The Excavations at Dura-Europos: Preliminary Report of the First Season of Work, Spring 1928. (Perusing HathiTrust is like walking the stacks of a multitude of great research libraries in one place. As a collection-of-collections, there is great pleasure in stumbling fortuitously across fascinating books that would not otherwise be available. Not only is the book on the excavations at Dura-Europos relevant today, the preface was written by James R. Angell, president of Yale University from 1921 to 1937. His father was James B. Angell who served as president of the University of Michigan from 1871 to 1909.)

The CRMS Toolkit demonstrates that with a great deal of effort it is often possible to make copyright determinations for books.

In many ways the impact of CRMS is felt most keenly in the way that the project opened a sense of possibility for a task that previously was so overwhelming as to seem insurmountable. The CRMS Toolkit demonstrates that with a great deal of effort it is often possible to make copyright determinations for books. Beyond books, it will be rather more challenging to tackle artifacts with multiple layers of copyright, for example serials, anthologies, or movies. CRMS explicitly excluded these kinds of works from its inquiry, but there is considerable anecdotal interest from colleagues in research libraries for us to address these kinds of materials in the future.

This is hard work.

In order to sustain copyright review at a large scale, you need grit.

In order to sustain copyright review at a large scale, you need grit. You also need to set realistic expectations. The productivity of the project may lead some to believe that this work is easy. It is not. For reviewers, copyright determination can be complex, tedious work. For team leaders, coordinating work at this scale can be very stressful.

Copyright review work requires great attention to detail but can be very repetitive at times, which is a factor in how long a person can stay focused at this task during the day. We learned that a doubled time commitment from reviewers did not result in doubled productivity. Instead, productivity dropped off as people committed to greater percentages of time.[15] We hope this observation can help institutions designing similar projects understand optimal time commitments for their review teams.

When working at this scale, the pressure to get things right can be a substantial source of stress. Team leaders must design processes that can stand up to scrutiny; small details can have a profound impact. Collaborating with experienced colleagues helped alleviate this stress; I cannot overstate our appreciation for the guidance and support we have received over the years. When operating in this area, seeking experienced counsel is very important.

In some respects, this is simply difficult work because we do not have all the facts necessary to make evaluations, even when we do know the law. But if around 30% of the works we looked at were too hard to evaluate and ended up in “undetermined” we did not despair. Our main goal was to review and open as many works as possible as efficiently as possible; this was a triage approach. While we do not have immediate plans to return to the body of undetermined material in the immediate future, members of the CRMS team recently completed an evaluation of part of this set regarding the closer evaluation of “inserts.” The immediate result of this is that we decided to change the order of operation of the evaluations: if a work has inserts, we will still review the book to see if it is in copyright or in the public domain generally. In that way, we can make a more nuanced decision about those books that may be in the public domain in their entirety—although some images may be subject to copyright or require further evaluation. I can envision this course of inquiry allowing us to consider a path for applying a fair use case to open books that are otherwise in the public domain. (At this time, fair use is not a consideration in HathiTrust evaluations.)

This work can be done

As Maureen Whalen, formerly of the general counsel’s office of the J. Paul Getty Trust, wrote in Rights Metadata Made Simple: “Yes, rights metadata can be complicated and overwhelming, but so is knitting a cardigan sweater until one simplifies the project by mastering a few basic techniques and following the instructions step-by-step.”

Like rights metadata, copyright review at this scale can appear to be an insurmountable challenge. CRMS made it possible by leveraging the work of a well-qualified and highly dedicated team and creating systematic processes. CRMS has expanded our sense of what is achievable.

This work cannot be done alone

Our excellent colleagues have meant everything to the project’s success. The quiet and dedicated work of CRMS reviewers, the often-unsung heroic work of catalogers, and the support of our Advisory Group have helped us forge ahead. Collaboration and encouragement from international colleagues—including the National Library of Israel, the British Library, Humboldt University’s iSchool, and the Universidad Complutense de Madrid—has helped remind us of the impact, importance, and opportunity represented by this work.

Many people and projects who were not official collaborators also made invaluable contributions to CRMS’s work. CRMS was possible because of HathiTrust and resources like the Stanford Copyright Renewal Database. Stanford’s project provided easy access to US copyright renewal records in a searchable database with an API. VIAF was not available when CRMS was conceived, but we added it to our suite of tools when it became apparent that it would improve our ability to identify author nationality and death date, both of which impact public domain status. At every turn, we built on the work of others.

Plan for human error

CRMS reviewers were extraordinarily attentive. They took their responsibilities seriously with an earnest recognition of the significance of their task. Still, we planned for human error. We provided close oversight for the work of the reviewers and instituted the double-review process with expert adjudication. Though we had great confidence in the trained reviewers, it was important to build a system of checks and balances that would transcend the need to put trust in any single individual—setting up the process carefully enabled us to put trust in the process and in the group as a whole.

Avoid bottlenecks

Structuring the workflow carefully is important when working at this scale. From the beginning, the CRMS reviewer role was designed in a way that accounted for change—the presence or absence of a single reviewer did not dictate system performance. However, the system did depend on individual expert reviewers. During the second and third grant periods, CRMS’s structure meant that the work of about 60 reviewers depended on the work of a few individuals.

This structure makes the project vulnerable to staffing changes. To address that, we examined what was necessary to continue the work should one person be hired away or even be away on vacation for a week. We implemented protocols so that individual absences would not have a negative impact on the team’s work. We improved documentation, both of training and of systems development. We cross-trained people to cover for other responsibilities and looked for areas that had become knowledge silos. We identified secondary responders in case the system went down while someone was out of the office.

At first, expert adjudication hinged on a single expert, which sometimes created substantial bottlenecks in our workflow. Over time, we distributed expert adjudication across several expert reviewers, training each of them on the expert adjudication process. This greatly reduced the burden on any one expert and allowed for much greater flexibility. In the past two years, individual experts have required considerable time off of the project and we have been able to shift resources quickly to accommodate their absence.

Collaboration requires leadership

CRMS represents a very successful collaboration across 19 partner institutions. In leading CRMS, our project team managed a number of complicated issues that illustrated the need for central administration and leadership in a large-scale collaboration.

A particularly striking example of the need for a project leader was our experience with cost-share. The IMLS grant required U-M and our partners to match the very generous IMLS funding of the project. We accomplished this in large part through partners allocating of staff time to CRMS. Whenever there was a change in personnel at a project partner institution, it represented a change in that institution’s ongoing financial commitment to CRMS. Thus, project personnel changes were never simple.

Cost-share administration can be very complex, and grows more so in the aggregate. As an example, if University A has made a commitment of 25 percent of a given employee’s time to a project, and that commitment equates to a $15,000 per year cost-share commitment, what happens if that employee retires? University A is still committed to a $15,000 per year cost-share with the project. But if University A tries to substitute a graduate student working ten hours a week at $15 per hour, that substitution would only represent a $7,800 commitment per year. University A would need to make up the difference of $7,200 each year.

Multiply this issue across nineteen partners, combine it with other project challenges, and you can imagine our administrative workload. No institution can, or should, carry the full burden of tackling this work. At the same time, patient leadership is essential to making certain that collaborations like these succeed.

Cultivate leaders

By the end of the third grant, our project team had gained invaluable expertise in getting this work done at a large scale. As the grant term came to a close, the CRMS project team faced instability and questions about the future. We were confronted by a reality that is increasingly prevalent at memory institutions—collectively, we rely on teams of dedicated, experienced professionals to identify solutions to enormous problems, often through grant funded activity. How do we protect and support our people when the work at hand is complete?

Here, we must take a serious look at the practices that leave so many of our colleagues in short term positions, with a corresponding need to look for work every two to three years. While this is intended to help organizations remain nimble in the face of massive upheaval, it threatens to erode our collective expertise and can eviscerate community building, an essential part of well-functioning organizations.

Do what you can

It can be easy to focus on what copyright review cannot accomplish or, alternatively, to be intimidated by the massive scale of the problem. We have found that taking one step at a time, moving towards copyright determinacy through the cooperative and distributed effort of our many partners, has resulted in an incredible inroad into the public domain.

Conclusion

Memory institutions must keep working to leverage the full value of public domain materials they hold. CRMS demonstrates that this work is possible on a large scale. When I look back on CRMS, I have to marvel at what it did to help deliver the public’s part of the copyright bargain. I also think about what is yet to be achieved.

Copyright determination cannot fulfill the bargain of copyright on its own—fair use and the specific exceptions and limitations to copyright are part of that bargain too.

First, while I firmly believe that copyright determination projects are essential to the future of memory institutions, I am equally convinced that copyright determination cannot fulfill the bargain of copyright on its own—fair use and the specific exceptions and limitations to copyright are part of that bargain too. While we work to identify public domain items in our collections, we must also exercise our rights to use materials that are protected by copyright. As we note in the Toolkit, the fair use doctrine often enables far better stewardship of our collections than copyright determination alone.

There are abundant opportunities for future copyright review. New languages and legal regimes are clear paths forward: a pilot project with Spanish-language works, described in the Toolkit, was a first step toward expanding CRMS beyond the English language. Copyright-eligible works other than books also present an enormous number of possibilities. Many non-book works (e.g., serials, movies, websites, etc.) require more extensive research. Designing a copyright determination system that can handle more complex works would be both a supreme challenge and wonderful achievement for our community.

The greatest benefit to future copyright determination work would come from additional information resources that facilitate copyright research. Just as our work benefitted from the Stanford Copyright Renewal Database and VIAF, future work will benefit from new information tools. Here, I am particularly excited by the possibility of a research project centered on identifying author death dates. Such a project could update authority records, capitalizing on existing infrastructure to share the information broadly. The results would enable copyright determinations on a per-author basis. Improved searchable records of all US copyright registrations, renewals, and transfers would also make a dramatic difference in what future copyright determination projects can achieve.

While memory institutions have made significant inroads into identifying public domain works, I am truly in awe when I consider the wealth and variety of works that await our attention.

While memory institutions have made significant inroads into identifying public domain works, I am truly in awe when I consider the wealth and variety of works that await our attention. The experience of CRMS indicates that we can tackle this challenge with improved information tools, carefully coordinated and distributed efforts, and ongoing advocacy and policy work. I have not specifically addressed the urgency and importance of advocacy and policy work. I view CRMS as policy-in-action. It reflects a cost being incurred by public institutions—educational institutions, libraries, and funders. Funding is scarce and would, ideally, be better spent on other aspects of our collective missions. As a community, we need to be robust in our knowledge of these issues so that we can communicate them effectively in support of meaningful library exceptions that work globally to simplify the identification of public domain works. It is one thing for the duration of copyright to be continually extended. It is entirely another thing to be unable to easily ascertain when that duration has actually expired. We can continue to do this challenging work while we press for effective laws and policies that respect the full span of copyright.

CRMS is a momentous beginning, and I am confident that it will not be the end of this important work.

Appendix A: The CRMS Community

The following institutions comprise the CRMS Community:

- Baylor University

- California Digital Library

- University of California, Irvine

- UCLA

- University of California, San Francisco

- Columbia University

- Dartmouth College

- Duke University

- University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

- Indiana University

- Johns Hopkins University

- University of Maryland

- McGill University

- University of Minnesota

- Northwestern University

- Ohio State University

- Penn State University

- Princeton University

- University of Wisconsin-Madison

- Three Institute of Museum and Library Services National Leadership Grants supported CRMS: LG-05-14-0042-14 (Principal Investigator John Wilkin), LG-05-08-0141-08 (Principal Investigator Melissa Levine), and LG-05-11-0150-11 (Principal Investigator Melissa Levine). I would like to thank Justin Bonfiglio and Ana Enriquez, copyright specialists in the Copyright Office at the University of Michigan Library, for their careful writing assistance. This issue brief is better for their help. ↑

- The Toolkit is available at cost print on demand (https://www.amazon.com/Finding-Public-Domain-Copyright-Management/dp/1607853736?ie=UTF8&redirect=true) and free as an ebook, (http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/crmstoolkit.14616082.0001.001). ↑

- ALA announces 2016 winner of L. Ray Patterson Copyright Award, http://www.ala.org/news/press-releases/2016/05/ala-announces-2016-winner-l-ray-patterson-copyright-award. ↑

- American Library Association, L. Ray Patterson Copyright Award, http://www.ala.org/advocacy/copyright/pattersonaward (accessed June 13, 2016). ↑

- For general information about accessibility and HathiTrust see https://www.hathitrust.org/accessibility (accessed May 27, 2016). ↑

- These numbers are as of June, 2016: https://www.hathitrust.org/visualizations_deposited_volumes_current. ↑

- John P. Wilkin, “Bibliographic Indeterminacy and the Scale of Problems and Opportunities of ‘Rights’ in Digital Collection Building,” February 2011. ↑

- See the Appendix for the list of community members. ↑

- These numbers are from February 26, 2016. ↑

- Jack Bernard, Associate General Counsel, University of Michigan; Kenneth D. Crews, Faculty Member, Columbia Law School, and Of Counsel, Gipson Hoffman and Pancione; Sharon E. Farb, Associate University Librarian for Collections and Scholarly Communication, UCLA; Bobby Glushko, Head, Scholarly Communications and Copyright, University of Toronto; Georgia K. Harper, Scholarly Communications Advisor, The University Libraries, University of Texas at Austin; Peter Hirtle, Affiliate Fellow, Berkman Center for Internet and Society, Harvard University; Jessica Litman, John F. Nickoll Professor of Law, University of Michigan Law School, and Professor of Information, University of Michigan School of Information; Kevin Smith, formerly the Director, Copyright and Scholarly Communication at Duke University Libraries and now Dean of Kansas University Libraries. ↑

- These numbers are from February 26, 2016. ↑

- One could envision other, more specialized projects where more time might be appropriately spent on a discrete set of works with a larger investment per review. ↑

- See the University of Michigan Library website for more information about the CRMS process: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/crmstoolkit. ↑

- See videos and slides of the presentation at the Digital Library Federation presentation organized by John Mark Ockerbloom, “Big Collections in an Era of Big Copyright: Practical Strategies for Making the Most of Digitized Heritage” at http://www.infodocket.com/2014/11/18/video-slide-presentations-big-collections-in-an-era-of-big-copyright-practical-strategies-for-making-the-most-of-digitized-heritage/ (accessed May 27, 2016). ↑

- Our current position is that a time commitment between 15–25 percent FTE (six to ten hours per week) is ideal. Reviewers will have sufficient time to retain skills without the risk of overload. ↑

Attribution/NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of the license, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.