Pell Restoration and Approval

Following the Data

Introduction

In 2020, the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) Simplification Act restored access to Pell Grants for students who are incarcerated, reversing a nearly 30-year ban on their eligibility for federal aid. To access Pell Grant funding, eligible students must be enrolled in federally recognized Prison Education Programs.[1] But, what does it mean for a Prison Education Program to be federally recognized? In this brief, we walk through the multi-year, multi-phase process to demystify the federal regulations and highlight its significance in improving higher education in prison data infrastructure—a critical need for the field.[2]

While the regulations governing Prison Education Programs remain in flux, particularly the future role of the US Department of Education, the data requirements embedded in the approval process are already shaping practice. These criteria matter for all higher education in prison programs, not just those pursuing Pell eligibility. To secure and maintain federal recognition, programs must collect robust, standardized data, but even those not seeking federal approval will need comparable practices to demonstrate impact, make evidence-based arguments for public support, and compete for philanthropic funding. With this context in mind, the following takeaways highlight what it takes to become a federally recognized Prison Education Program.

The data requirements embedded in the approval process are already shaping practice.

Key takeaways

- Oversight entities have significant discretion over the criteria that colleges and universities operating higher education in prison programs must meet to secure and maintain Prison Education Program status. In most cases, state departments of corrections serve as the oversight entity, which means that specific approval criteria will likely vary by state, although the extent of this variation remains unclear.

- The process to becoming a Pell eligible program is not a straight line and may seem daunting. To secure and maintain federal recognition, Prison Education Programs and the higher education institutions that house them must obtain approval from oversight entities, accreditors, and ED; undergo a period of program monitoring; and ultimately pass a Best Interest Determination.

- Collecting and sharing data are integral to every step of the process. Oversight entities, higher education institutions, and departments of corrections all play critical roles in ensuring that data such as enrollment, transfer, and release information flows smoothly across agencies so that programs can demonstrate they are operating in the best interest of students.

Background

On July 1, 2023, building on the success of the 2016 Second Chance Pell Experiment, Congress reinstated Pell Grant eligibility for individuals who are confined or incarcerated throughout the United States.[3] The legislation established a process for higher education in prison programs to become federally recognized Prison Education Programs. Students who are incarcerated must be enrolled in a Prison Education Program and meet all other Title IV eligibility criteria to qualify for Pell Grant funding.[4] To become a Prison Education Program, higher education institutions operating prison programs must secure provisional approval from their oversight entities (typically state departments of corrections), accrediting agencies, and the US Department of Education (ED); regularly submit data to ED for program monitoring; and pass ED’s Best Interest Determination, a holistic assessment to determine if programs are operating in the best interest of their students.

The restoration of Pell Grant funding for incarcerated learners and the development of the Prison Education Program designation brings new scrutiny to how programs collect and manage data. Correctional agencies and oversight entities are now developing assessment criteria in line with federal policy and engaging programs and their higher education institutions on data requirements for Prison Education Program recognition. At the same time, the availability of Pell funding in the sector has significantly heightened public interest in higher education in prison and made it more financially viable for universities and community colleges to offer qualifying programming to incarcerated students.

Research on need-based financial aid consistently shows that grants help low-income students by reducing financial barriers to college. The federal Pell Grant program and similar initiatives have resulted in lower dropout rates and higher college attendance, persistence, credit completion, and graduation rates. At the same time, these policies are not without challenges: difficult application processes, unclear eligibility requirements, and complicated standards for students to maintain their aid over time can create unintended barriers for students.[5] Some critics, however, argue that increased federal aid availability has contributed to rising tuition and fees, though most of the supporting evidence is not causal and relates to federal loans rather than federal grant programs, like Pell.[6] Despite the extensive research on financial aid more broadly, little is known about the potential benefits and challenges of financial aid for students who are currently or formerly incarcerated. With Pell restoration, more research is needed to assess outcomes and identify challenges specific to this population.

While research on financial aid has largely overlooked the effects of Pell Grant funding for students who are incarcerated, past policy changes provide insights into its potential impact. The 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act eliminated Pell Grant access for incarcerated learners, leading to a 44 percent drop in enrollment—over 20,000 students—within a year.[7] Recently, the 2016 Second Chance Pell Experimental Sites Initiative provided Pell funding to this population of learners in participating higher education programs, enrolling over 40,000 students across 200 programs from 2016 to 2022. Analysis by the Vera Institute of Justice found that, aside from the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, these programs saw steady increases in enrollment, credential attainment, and degree completion.[8] Taken together, these effects suggest that expanding access to federal financial aid represents a critical opportunity to increase enrollment and improve the quality of higher education in prison programming.

Despite the growing importance of and interest in Pell for students who are incarcerated, the path to Pell-eligibility is not simple. Not only is the process complicated, but many programs and institutions do not yet have the data needed for Prison Education Program approval. Last fall, we launched a research project aimed at strengthening data collection, data availability, and data use across the field of higher education in prison.[9] Our first report outlined the key barriers and opportunities facing the field as it works to build a more comprehensive and sustainable data infrastructure, and we draw on insights from the interviews conducted for that report throughout this brief.[10] In conducting that research, we learned that many stakeholders involved in the approval process often had only a limited understanding of what is needed to become a Prison Education Program and maintain that federal recognition over time. While research and technical assistance organizations have published information about the return of Pell funding for students who are incarcerated, our research indicates a continued need for clear, accessible mapping to demystify this process.

To help meet those needs, this issue brief maps out and clarifies the federal Prison Education Program approval process for relevant stakeholders. We begin with a brief history of Pell Grant funding for incarcerated students, then describe the new approval process, and end with a discussion of why a high-level framework is needed to chart connections and trace data flows across stakeholders. Such a resource would be especially valuable for program administrators who must determine whether and how their program and institution can meet the

data collection and reporting requirements tied to the Best Interest Determination at the end of the initial approval process.

Pell Grant restoration for incarcerated learners

The 1972 reauthorization of the Higher Education Act established the federal Pell Grant program, and its provisions allowed for eligible incarcerated individuals to receive this funding. Higher education in prison programs grew rapidly over the next two decades,[11] but Pell Grant eligibility criteria for incarcerated learners was curtailed by a 1992 amendment to the Higher Education Act.[12] In 1994, the passage of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act barred individuals in federal or state penal institutions from receiving any federal Pell Grants.[13] This restriction held until 2015, when the US Department of Education (ED) launched the Second Chance Pell Experimental Sites Initiative, which provided Pell Grant funding to qualified incarcerated learners in state and federal prisons enrolled in participating higher education in prison programs. Between 2016 and 2022, 200 programs were invited to participate in the initiative, representing over 40,000 students.[14] ED required these programs to submit student-level data to the initiative’s technical assistance provider, the Vera Institute of Justice.

Building on the success of the Second Chance Pell experiment, Congress formally expanded access to Pell Grant eligibility for individuals who are incarcerated through the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) Simplification Act of 2020. The Act amended the Higher Education Act of 1965 to restore Pell Grant eligibility for individuals incarcerated in federal or state correctional facilities attending approved Prison Education Programs.[15] This established a new federally-recognized subcategory of higher education in prison programs that could receive Pell Grant dollars, known as Prison Education Programs. Accordingly, ED revised the Second Chance Pell initiative in 2023 to provide participating programs with up to three additional years of Pell funding while they file for Prison Education

Program approval.[16] Once the initiative concludes, only programs that have secured this approval and federal recognition will remain Pell eligible.

Becoming a Pell-eligible program

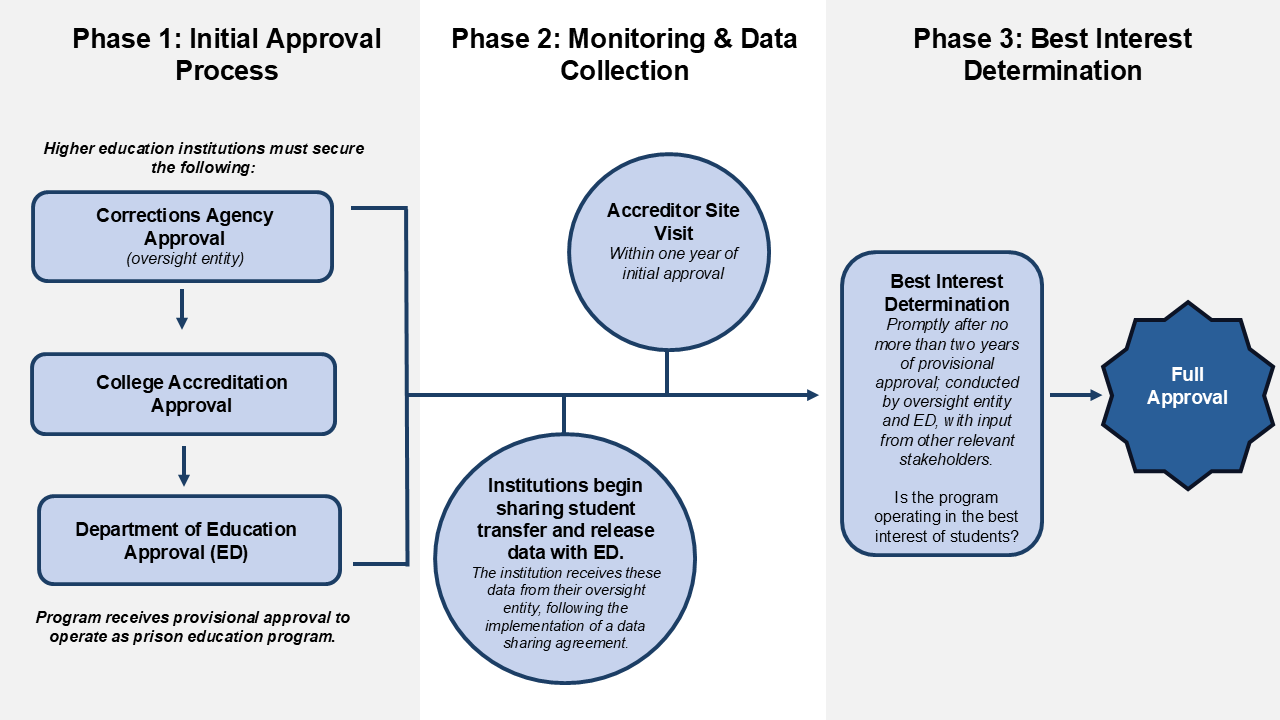

New and existing programs seeking Prison Education Program approval and the ability to receive Pell funding must undergo a multi-year application process, which includes three core phases: the initial approval process, a roughly two-year period of program monitoring and data collection, and the Best Interest Determination process (Figure 1).

These phases, which take a minimum of two years to complete, are outlined by the US Department of Education (ED) in their general guidelines for the Prison Education Program approval process, released in October 2022.[17] Several agencies and entities are involved at various stages of the process, including accreditation agencies and state departments of corrections, but the higher education institutions that operate higher education in prison programs are the parties ultimately responsible for submitting the Prison Education Program application.

As of September 30, 2025, no Prison Education Programs are far enough into the two-year process to have obtained full approval by completing all three phases of the approval process (see figure 1 below). The first Prison Education Programs received provisional approval in June 2024, and as of December 4, 2024 (the last update provided by ED), 21 programs have received provisional approval. [18] We do not know the number of programs in the Phase 1 pipeline because ED does not share who is currently applying for approval nor the average time it takes for a program to receive provisional approval.

Figure 1. Prison Education Program approval process

Phase 1: Provisional approval

In the first phase, the higher education institution who operates and houses the Prison Education Program must secure approval from three key parties to receive Pell dollars: the oversight entity (typically the state department of corrections), the institution’s accrediting agency, and ED. Once the oversight entity and accreditor sign off, the institution submits a final application to ED. ED then grants provisional approval, making the program Pell Grant-eligible. This process ensures that the agencies overseeing the program are aligned on its offerings and operations. Prior to this process, few structures were in place to ensure these entities had relevant and up-to-date program information, often leaving communication and coordination to individual program discretion and capacity.

The first step in the approval process requires colleges and universities to engage with their oversight entity to obtain documentation that they are approved to operate in a designated facility or set of facilities. While the agency fulfilling this role can vary, in most cases the state department of corrections (DOC) will serve as the oversight entity for programs operating in state facilities, with the Federal Bureau of Prisons filling the role for programs operating in federal facilities. ED regulations task DOCs with determining whether a proposed Prison Education Program aligns with the mission and standards of the correctional facilities under their authority. While DOCs have wide discretion in this determination because the regulations provide no specific criteria for them to follow, they must report the methodology behind their decision to ED as the final step of this phase. As we learned through our interviews, in many states, oversight entities, accreditation agencies, and ED have collaborated to align documentation and criteria for this phase 1 determination.

Following oversight entity approval, higher education institutions must then seek approval from their accrediting agency. Because Prison Education Programs are considered additional locations, or branch campuses by ED, the institutions are required to submit substantive change applications to their accreditor to establish a new location within a correctional facility and explain how they have the ability to operate a Prison Education Program and comply with the accreditor’s requirements for such programming.[19] To help guide accreditors and peer reviewers in their assessment of Prison Education Programs, the Vera Institute of Justice collaborated with the Higher Learning Commission to develop a guidebook with suggested measures and areas of inquiry to ensure Prison Education Program quality across accrediting agencies.[20]

The final step of the initial approval process requires higher education institutions to submit a comprehensive Prison Education Program application to the ED. Application requirements include a detailed description of the program and credentials offered to students; documentation of oversight entity and accreditation agency approval; the specific criteria the oversight entity used to approve the program; the support services that will be provided to students participating in the program; and confirmation that the program will provide all necessary data to the oversight entity and ED for program monitoring. ED’s approval of the application confers provisional approval to the Prison Education Program for up to two years.

Phase 2: Program monitoring and data collection

After receiving provisional Prison Education Program status, programs enter into the second phase of the approval process. In this phase, institutions, working with their oversight entity, must submit student transfer and release date data to ED. This follows a component of the application in which the oversight entity and institution enter into an agreement guaranteeing the institution receive data about transfer and release dates of incarcerated individuals from the oversight entity. Within the agreement, the expiration date of the agreement and frequency of data sharing is defined. Institutions must also meet reporting requirements and deadlines set by ED and published in the Federal Register. Additionally, the institution’s accreditation agency will perform a site visit. The site visit must occur within one year of the program’s provisional approval, is required for the first two sites if the program is operating across multiple correctional facilities, and is required for the first instance of the program being provided via a new method of delivery. Each accrediting agency has its own guidelines and criteria for evaluating programs during the site visit.

Phase 3: Best Interest Determination

The final phase of the approval process consists of a comprehensive program review, led by the institution’s oversight entity, to assess whether the program is operating in the best interest of students. This process, called the Best Interest Determination, must occur promptly after no more than two years of the program receiving provisional approval.[21] ED has issued broad guidelines for the Best Interest Determination, but many details remain at the discretion of the oversight entity—including which metrics to use, how to measure them, how programs should present evidence, and which metrics will matter most in making a final determination. The ambiguous nature of this guidance could be helpful in accommodating the geographic and logistical constraints of higher education in prison programs, where variation in outcomes may reflect context rather than program quality. Some organizations have developed resources to assist oversight entities in the development of their Best Interest Determination criteria, such as the Vera Institute of Justices’s Best Interest Determination Toolkit, informed by representatives from state departments of corrections, higher education institutions, state government agencies, and relevant national organizations.[22]

Though oversight entities retain significant discretion in the process, ED has specified that the determination must include, at a minimum, an assessment of the required criteria shown below.

Table 1. Required criteria for Best Interest Determination

| Instructor experience and credentials | Programs must provide information on their instructors’ experience, credentials, and turnover rate and compare these factors to those of instructors in other programs at the institution. |

| Transferability of credits | Programs must explain how the credits earned in their programs transfer and apply toward related degrees or certificates within the institution, comparing them to credits earned in similar programs at the institution. |

| Availability of student services | Programs must assess whether the academic and career advising services offered to incarcerated students—while they are incarcerated, before reentry, and after release—are comparable to those available to non-incarcerated students at, and possibly transferring from, the same institution. |

| Continuity of study | Programs must provide information about whether students can fully transfer their credits and continue in their program at any campus or location of that institution offering a comparable program. |

ED’s guidelines also suggest additional optional criteria the oversight entity can include in their determination, such as students’ recidivism rates, completion rates, rates of continuing education enrollment post-release, job placement rates, and post-release earnings information. However, the oversight entity has discretion in determining how to measure the required and optional criteria, thereby defining what “best interest” ultimately looks like.

Oversight entities lead the Best Interest Determination process, but they must incorporate stakeholder feedback, including from:

- Representatives of individuals who are incarcerated

- Organizations representing individuals who are incarcerated

- State higher education executive offices

- Accrediting agencies

Decisions are not always a simple pass or fail—programs may receive conditional approval or be required to make improvements before receiving full recognition as a Prison Education Program. Best Interest Determination is a holistic process in which a program may be deemed as serving students’ best interests even if they do not meet every requirement.

Failure to gain full approval has significant consequences. If a program is deemed “ineligible,” students enrolled in that program will lose access to Pell Grant funds starting with the next payment period. However, programs that do not pass the Best Interest Determination may reapply in the future, with the timing of the next application determined by the oversight entity.

The Best Interest Determination must be conducted as part of the Prison Education Program approval process, but it is not a one-time requirement. Institutions must also undergo this determination to renew their Program Participation Agreement with ED, which is part of a typical accreditation process for institutions. The Program Participation Agreement authorizes the institution to administer federal financial aid and must be renewed every six years. As a result, the Best Interest Determination process may need to be repeated as soon as the following year or up to six years after a program receives approval to operate as a Prison Education Program, depending on when within the typical six-year accreditation cycle the institution receives approval. Additionally, the oversight entity has the discretion to require more frequent reviews and may make a determination between subsequent evaluations based on program outcomes or other forms of monitoring.

Pell approval as a beginning, not an end

It is crucial that higher education in prison program leaders, correctional education officials, and higher education institution administrators understand what is required for Prison Education Program approval, how the process works, and what outcomes it is designed to achieve. This brief aims to clarify and demystify those processes so that stakeholders can see the entire picture, while recognizing that the process is also highly context dependent. Oversight entities–typically state departments of corrections–hold substantial discretion in setting provisional and full approval criteria for the programs they oversee. How these criteria will vary across states or between programs operating in state or federal carceral facilities remains unclear; therefore, this issue brief focuses on the criteria and guidelines that apply across states.

While the brief seeks to clarify aspects of the Prison Education Program approval process, the funding for and oversight of the Pell Grant program overall is uncertain. During US Congressional budget debates for the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, major revisions to the Pell program were under consideration, raising concern that funding for incarcerated students could be reduced or revoked. Ultimately, the budget resolution (H.R. 1 of the 119th Congress, 2025-2026), expanded Pell Grant funding through “Workforce Pell,” which extends eligibility to short-term job-training programs.[23] How that will be implemented procedurally and what impacts it might have on higher education in prison programs remains unclear. For now, however, Pell eligibility and availability for incarcerated students appears largely unchanged.

The US Department of Education (ED) has also undergone substantial changes since the guidelines for Prison Education Programs were first established, including significant reductions in staff by the new administration during the first half of 2025.[24] The role that ED will play in Prison Education Program oversight—both in the near and long term—remains uncertain as the field awaits further guidance from federal agencies. Some effects of staff reductions are crystallizing: for instance, while the Federal Student Aid website indicates that ED will provide quarterly updates on approved programs, the list has not been updated since December 2024. Given ED’s central role in recognizing and monitoring Prison Education Programs, significant changes to the approval process may be on the horizon.

The restoration of federal Pell Grant eligibility for incarcerated students is not an endpoint but the beginning of a new phase of federal oversight for higher education in prison programs. Given the data requirements outlined in federal regulation and developed by program oversight entities, the Prison Education Program approval process marks the first step toward developing a stronger data ecosystem that enables program evaluation and meaningful comparison across the field of higher education in prison. The challenges surfaced through the approval process highlight the importance of developing high-quality data gathering and evaluation practices to assess the effectiveness of specific program components and to compare quality within and across programs.[25]

Pell funding has the potential to help programs expand, encourage them to more fully integrate and connect with resources from their home institutions, and broaden the range of educational opportunities offered—but these outcomes are not guaranteed. What is already apparent is that meeting that potential will require a more robust and standardized data infrastructure. The need for better data infrastructure will extend beyond programs with Pell approval: institutions that choose not to pursue approval will still need to develop comparable data collection and evaluation paradigms if they want to be able to demonstrate the effectiveness of their programming, make evidence-based arguments for increased public support for higher education in prison, and compete for philanthropic funding. All higher education in prison programs should therefore pay close attention to the approval process and its criteria.

Endnotes

- Higher Education in Prison (HEP) is an informal designation for prison education programs in the field. Prison Education Program (PEP) is used as both an informal designation and an official designation given to prison education programs seeking authorization to or authorized by the US Department of Education to award Pell Grants. Throughout, we use higher education in prison to refer to programs generally and Prison Education Program to refer to those seeking authorization or are authorized to offer Pell Grants. ↑

- Alex Monday, Bethany Lewis, Sindy Lopez, Tommaso Bardelli, Elizabeth Davidson Pisacreta, Jessica Pokharel, and Ess Pokornowski, “Why Data and Why Now? The Importance and Challenges of Data for Higher Education in Prison,” Ithaka S+R, August 20, 2025, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.323415. ↑

- “US Department of Education to launch application process to expand federal Pell Grant access for individuals who are confined or incarcerated,” Department of Education: Press Release, June 30, 2023, Accessed 1 January 2025, View the last active snapshot of the page in Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, January 17, 2025: https://web.archive.org/web/20250117083636/https://www.ed.gov/about/news/press-release/us-department-of-education-to-launch-application-process-to-expand-federal-pell-grant-access-for-individuals-who-are-confined-or-incarcerated. ↑

- For the full list of Pell Grant eligibility criteria, see 34 CFR Part 668 Subpart C – Student Eligibility, https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-34/subtitle-B/chapter-VI/part-668/subpart-C. ↑

- Sara Goldrick-Rab, Paying the Price: College Costs, Financial Aid, and the Betrayal of the American Dream (Chicago, Il: University of Chicago Press, 2016); Lauren Schudde and Judith Scott-Clayton, “Pell Grants as Performance-Based Scholarships? An Examination of Satisfactory Academic Progress Requirements in the Nation’s Largest Need-Based Aid Program,” Research in Higher Education 57 (March 17, 2016): 943-967. ↑

- Jenna A. Robinson, “The Bennett Hypothesis Turns 30,” James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal, 2017, https://jamesgmartin.center/2017/12/the-bennett-hypothesis-turns-30/. ↑

- Meagan Wilson, Rayane Alamuddin, and Danielle Cooper, “Unbarring Access: A Landscape Review of Postsecondary Education in Prison and Its Pedagogical Supports,” Ithaka S+R, May 30, 2019 https://sr.ithaka.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/SR-report-landscape-review-postsecondary-education-in-prison-053019.pdf ↑

- Niloufer Taber and Asha Muralidharan, “Second Chance Pell: Six Years of Expanding Higher Education Programs in Prisons, 2016-2022,” Vera Institute of Justice, April 2024, https://vera-institute.files.svdcdn.com/production/downloads/publications/second-chance-pell-six-years-of-expanding-access-to-education-in-prison.pdf. ↑

- Tommaso Bardelli, Alex Monday, Elizabeth Davidson Pisacreta, “Building Data Collection and Evaluation Capacity for Higher Education in Prisons,” Ithaka S+R, September 27, 2024, https://sr.ithaka.org/blog/building-data-collection-capacity-for-higher-education-in-prisons/. ↑

- Alex Monday, Bethany Lewis, Sindy Lopez, Tommaso Bardelli, Elizabeth Davidson Pisacreta, Jessica Pokharel, and Ess Pokornowski, “Why Data and Why Now? The Importance and Challenges of Data for Higher Education in Prison,” Ithaka S+R, August 20, 2025, https://sr.ithaka.org/publications/why-data-and-why-now/. ↑

- Gerard Robinson and Elizabeth English, “The Second Chance Pell Pilot Program: A Historical Overview,” American Enterprise Institute, September 2017, https://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/The-Second-Chance-Pell-Pilot-Program.pdf#page=2. ↑

- S.1150 – Higher Education Amendments of 1992, 102nd Congress (1991-1992), Congress.gov, https://www.congress.gov/bill/102nd-congress/senate-bill/1150. ↑

- H.R.3355 – Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, 103 Congress (1993-1994), https://www.congress.gov/bill/103rd-congress/house-bill/3355/text. ↑

- Niloufer Taber and Asha Muralidharan, “Second Change Pell: Six Years of Expanding Higher Education Programs in Prisons, 2016-2022,” Vera Institute of Justice, June 2023, https://vera-institute.files.svdcdn.com/production/downloads/publications/second-chance-pell-six-years-of-expanding-access-to-education-in-prison.pdf. ↑

- Benjamin Collins and Cassandria Dortch, “The FAFSA Simplification Act,” Congress.gov, August 4, 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46909. ↑

- “Application: Postsecondary Educational Institutions to Participate in Experiments Under the Experimental Sites Initiative,” Federal Student Aid, April 18, 2023, https://fsapartners.ed.gov/knowledge-center/library/federal-registers/2023-04-18/application-postsecondary-educational-institutions-participate-experiments-under-experimental-sites-initiative. ↑

- 34 CFR Part 668 Subpart P – Prison Education Programs, https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-34/subtitle-B/chapter-VI/part-668/subpart-P. ↑

- “Approved Prison Education Programs,” Federal Student Aid, Updated December 4, 2024, https://studentaid.gov/data-center/school/pep. ↑

- For an example, see the Middle States Commission on Higher Education’s (MSCHE) “New PEP Additional Location | Reclassification of OIS to PEP Additional Location” substantive change application, https://www.msche.org/substantive-change/. ↑

- “Postsecondary Education in Prison Programs and Accreditation – General Considerations for Peer Reviewers and Accreditors,” Vera Institute of Justice, October 2022, https://www.vera.org/publications/postsecondary-education-prison-accreditation-guidebook. ↑

- The deadline to submit the Best Interest Determination to ED is dependent upon the status of the institution’s Program Participation Agreement (PPA). If the end of the two-year period of provisional approval for the Prison Education Program occurs within 12 months of the expiration date for the PPA, the Best Interest Determination is due to ED within 120 days of the PPA expiration. If the PPA will not expire within 12 months of the end of the program’s provisional approval date, the Best Interest Determination is due to ED no later than 90 days after the end of the two-year provisional approval date. See: “Prison Education Programs Questions and Answers,” US Department of Education, https://www.ed.gov/laws-and-policy/higher-education-laws-and-policy/prison-education-programs-questions-and-answers#app. ↑

- “The Best Interest Determination (BID) Toolkit: Guidance for Oversight Entities,” 2024 Best Interest Determination Council, Corrections Education Leadership Academy, and the Vera Institute of Justice, March 2025, https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5e3dd3cf0b4b54470c8b1be1/67e449ed37fb817b8a01b8c6_BID%20Toolkit.pdf. ↑

- To examine the full bill as it was passed, see: https://www.congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/house-bill/1/text. For more information about the amendment to add Workforce Pell Grants, see in above: SEC. 83002. WORKFORCE PELL GRANTS. ↑

- “Improving Education Outcomes by Empowering Parents, States, and Communities,” Executive Orders, the White House, March 20, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/03/improving-education-outcomes-by-empowering-parents-states-and-communities/. ↑

- Alex Monday, Bethany Lewis, Sindy Lopez, Tommaso Bardelli, Elizabeth Davidson Pisacreta, Jessica Pokharel, and Ess Pokornowski, “Why Data and Why Now? The Importance and Challenges of Data for Higher Education in Prison,” Ithaka S+R, August 20, 2025, https://sr.ithaka.org/publications/why-data-and-why-now/. ↑