State Uses of IPEDS Data

Insights for Strengthening the National Postsecondary Education Data Infrastructure

Executive summary

State agencies rely on the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) as an essential part of their postsecondary education data systems. The system provides common definitions and standardized indicators that enable consistent measurement across institutions and states, enabling institutional and state comparisons, accountability frameworks, performance funding, and public and legislative reporting. IPEDS definitions are widely adopted within state data systems and are used to validate state-collected data.

In collaboration with the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association (SHEEO), and with support from Lumina Foundation, we explored how state higher education agencies use data from IPEDS, the challenges they encounter, and their perspectives on the future of the federal postsecondary education data collection. In this report, we share our findings from a national survey as well as interviews with fourteen SHEEO leaders, including directors and specialists in research, data, and analysis, as well as several senior executives and commissioners.

Findings in this study reveal that state agencies continue to depend on IPEDS for reliable national benchmarks and coverage that extends beyond state boundaries. The data are particularly important for analyses that include independent and proprietary institutions, as well as for comparisons of tuition, financial aid, net price and completion outcomes. In certain cases, state legislatures require reporting that depends on IPEDS data, which are used for performance measures. State agencies also use IPEDS data to inform decisions about tuition and fee setting, financial aid awards, and institutional funding, underlying the data’s role in state policy making and resource allocation.

While state agencies are generally confident in the value and quality of IPEDS, they also identified several limitations. Respondents noted that IPEDS data are often released too late to inform state policy or budget decisions, and some suggested that either shorter release windows or preliminary data releases would be helpful. Others, however, emphasized the importance of data validation and quality assurance, creating a tension between timeliness and quality. Representatives from state agencies also described challenges related to limited data coverage (e.g., on non-credit activities), the functionality of IPEDS public tools, and inconsistencies in institutional reporting.

The report also explores state agencies’ readiness for potential disruptions to IPEDS. Recent changes to federal staffing and operations, including at the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), have created uncertainty about IPEDS’ stability and resourcing.[1] Although some state agencies have discussed contingency planning, few reported being well prepared to replace IPEDS data or tools if they became unavailable. Roughly four in ten respondents said their agency was concerned but not sufficiently prepared for such a disruption, and a similar share noted that discussions were underway but no plans had been implemented.

Overall, the survey and interviews show that IPEDS continues to serve as a vital component of the postsecondary education data infrastructure. State agencies rely on it to maintain comparability and transparency in higher education reporting, even as they work to expand their own data systems. Improving timeliness, expanding data coverage, and ensuring consistent federal support will strengthen the partnership between federal and state agencies and help preserve a coherent national postsecondary education data infrastructure that serves policymakers, institutions, and the public.

Introduction

IPEDS has been a foundational element of postsecondary education data in the United States for over four decades. Administered by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), it provides a comprehensive, federally maintained collection of institutional-level information covering all Higher Education Act of 1965 (HEA) Title IV-participating postsecondary institutions (i.e., those that award federal student financial aid).[2] For state agencies, IPEDS serves not just as a way for the federal government to collect required data from colleges and universities to inform its student financial aid programs. It also serves as a common framework for understanding the higher education environment across state lines, and allows states to understand their postsecondary systems’ performance within the broader national context.[3]

As states pursue goals related to attainment, opportunity, and workforce alignment, their information needs have become increasingly complex.

As states pursue goals related to attainment, opportunity, and workforce alignment, their information needs have become increasingly complex. Many have built their own data systems, including state longitudinal data systems (SLDS) that link postsecondary records to K–12, labor, and other state administrative data, enabling analyses that go beyond IPEDS’ institutional-level data-reporting approach. In its most recent Strong Foundations 2023 report, SHEEO describes continued progress being made by state agencies in the development and maturity of these longitudinal data systems across the country.[4] IPEDS and other federal data collections represent a key complement to these state efforts.

Our findings show that IPEDS remains an essential resource for states, alongside their expanded state systems. A recent report by the Institute for Higher Education Policy (IHEP) highlights the essential role of federal datasets, including IPEDS, in shaping state research agendas and policy frameworks.[5] IHEP’s findings reveal that states rely on NCES data for benchmarking, performance measurement, and evidence-based policymaking. The findings from this national survey and accompanying interviews reinforce the IHEP findings and build upon them.

This report examines how state agencies incorporate IPEDS into their policy work, what benefits and limitations they experience, and where coordination between state and federal systems might be strengthened. Through a combination of survey and interview data, it offers a state perspective on IPEDS’ role within the evolving postsecondary education data infrastructure.

Approach

This research employed a mixed-methods approach designed to capture both the breadth of state practices and the depth of state perspectives on IPEDS. Ithaka S+R conducted the research in collaboration with SHEEO. Ithaka S+R is a nonprofit that is dedicated to increasing access to higher education and improving student outcomes through research and strategic advising. SHEEO, founded in 1954, serves the chief executives of statewide governing, policy, and coordinating boards of postsecondary education and their staff.

Interviews

The first phase of this research consisted of interviews with representatives from ten state higher education agencies, conducted in person at the SHEEO Higher Education Policy Conference in August 2025. Conversations were semi-structured and focused on how state agencies use IPEDS for accountability, funding, and public reporting; what limitations they encounter; and how coordination between state and federal data systems might be strengthened. Interview notes were analyzed for common themes across respondents. Insights from these interviews also informed the final survey design.

Survey design and administration

The second phase of the research was an expedited national survey (administered in September 2025) developed by Ithaka S+R in collaboration with SHEEO and distributed through the SHEEO member network. Thirty-one state agencies responded, representing just under half of SHEEO’s 63 state and territorial members and covering a broad cross-section of governance structures.

The survey collected information on the frequency and purposes of IPEDS use, integration with state systems, reliance on IPEDS definitions, challenges in use, and the types of support agencies provide to institutions. Analyses are descriptive, reporting the experiences and perspectives of responding agencies.

Respondent characteristics

Respondents were typically senior research or data officers responsible for IPEDS coordination and state reporting at their SHEEO agency. Nearly all respondents (90 percent) have research or data analytics teams within their state agencies. Responding agencies report having some responsibility for some combination of four-year institutions (94 percent), two-year institutions (71 percent), and/or less-than-two-year institutions (32 percent). Many of the agencies also provide IPEDS-related services to their institutions, including state coordinator assistance and data quality feedback before federal submission (61 percent), provision of IPEDS datasets to institutions (45 percent), and creation of custom data extracts on request (42 percent). Fewer agencies provide training workshops and webinars (10 percent), or peer comparison tools built on IPEDS (19 percent).

Findings

State agencies rely heavily on IPEDS for benchmarking, accountability, funding, and compliance reporting. Across responses, participants emphasized that IPEDS provides a national standard for definitions, data comparability, and peer comparisons, while also filling major gaps in areas where state agencies lack their own data collection. At the same time, they noted persistent challenges with timeliness, usability, and inconsistencies in institutional reporting.

The specific findings below are drawn from both the survey results and the interviews. All results are anonymized to protect the confidentiality of respondents.

Perceived value of IPEDS

Respondents described IPEDS as a primary reference point for higher education data. It provides a known, national framework that enables comparisons across institutions and state boundaries and fills gaps in areas where state agencies lack their own collections, particularly for independent and proprietary institutions. IPEDS definitions are viewed as the “gold standard,” ensuring consistency and comparability across jurisdictions. As one research director observed, “IPEDS gives us a shared language. It ensures that everyone means the same thing when we talk about graduation rates or completions.”

“IPEDS gives us a shared language. It ensures that everyone means the same thing when we talk about graduation rates or completions.”

State agencies noted that IPEDS has value when it comes to credibility and scope, serving as an authoritative source for postsecondary education data. State agencies rely on its terminology and methodologies to anchor their own collections and cross-check or confirm their results. One respondent described IPEDS as “invaluable, not just for benchmarking data and supplementing our state’s longitudinal data system but also in the common data definitions.” Another called IPEDS definitions “trusted references and gold standards when we create institutional-level metrics and reports.”

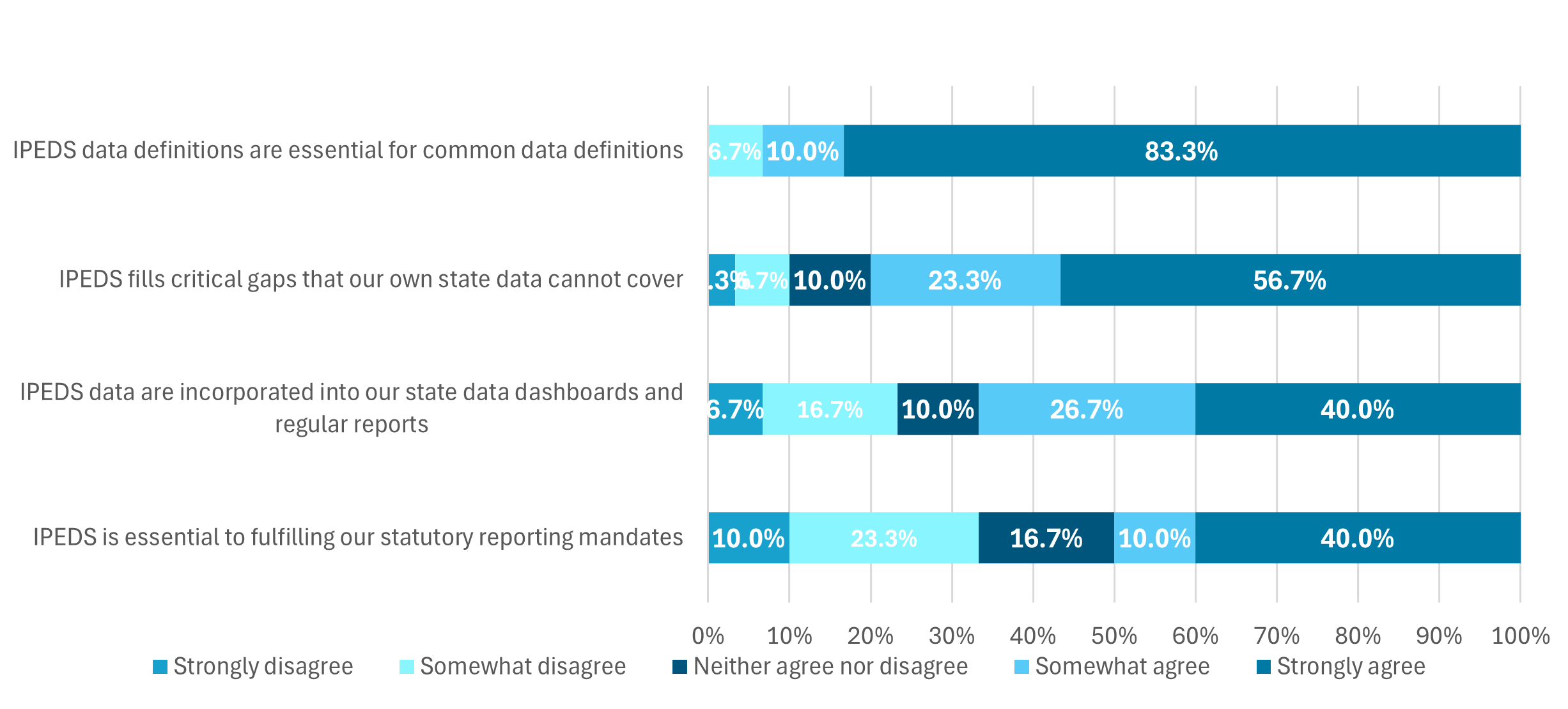

These perceptions align closely with the survey results summarized in Figure 1, which show that respondents view IPEDS as most important for providing common data definitions, filling gaps in their own state data, and, to a lesser but still notable extent, supporting dashboards and statutory reporting requirements.

Figure 1. Importance of IPEDS for State Data Activities

Percent of responding agencies agreeing that IPEDS is important for each function

Building on these perceptions, the survey and interviews provide detailed evidence of the specific ways state agencies use IPEDS data to inform policy, manage accountability systems, and maintain consistency across institutions.

Foundational uses of IPEDS data

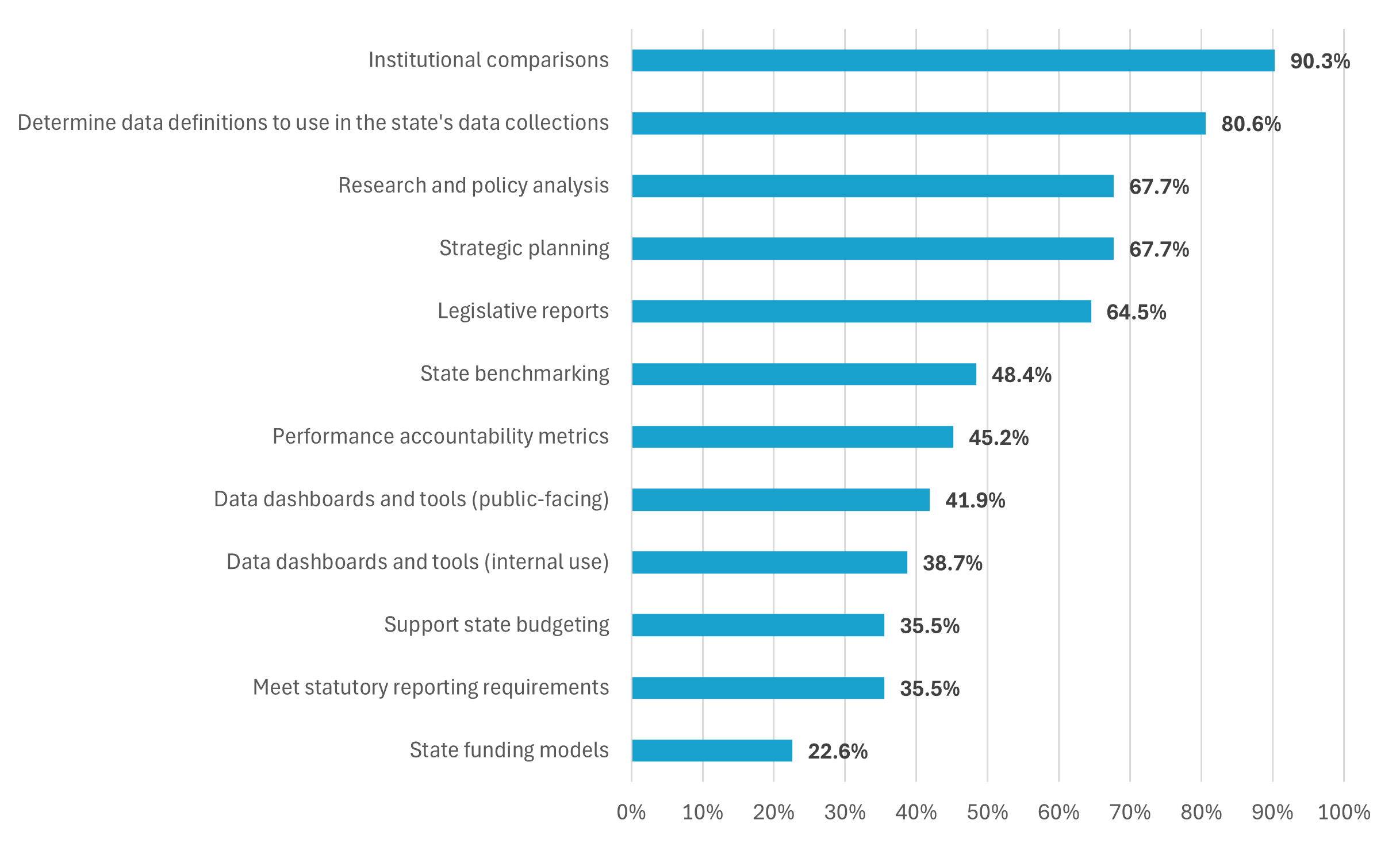

Across both the interviews and the survey, state agencies described IPEDS as a key complement to their own data collections and analyses. Respondents reported a broad range of uses for IPEDS data, spanning benchmarking, definitions, policy planning, and accountability (see Figure 2). The most frequently cited uses, according to 90 percent of responding agencies, were for regional and national comparisons and institutional benchmarking. IPEDS is critical for enabling cross-institutional examination and benchmarking; for many states, IPEDS is the only source of data on the characteristics and outcomes of private nonprofit and for-profit institutions in their state. As one respondent explained, “At its most basic, IPEDS is our first and best way to benchmark our institutions against others in the state and nationally.” Another noted the value of this function for pricing and affordability analyses: “We use IPEDS data to compare our institutions to the tuition and fees at public four-year institutions in the surrounding states.”

About eight in ten agencies (81 percent) said they rely on IPEDS to determine data definitions for their own state collections. One respondent described IPEDS definitions as “the backbone to all our definitions. We always go to them first.” Another noted, “We typically look to the IPEDS definition to be the standard when collecting data from our institutions.” Several agencies reported adopting IPEDS variables directly into their data dictionaries or longitudinal systems so that state-collected data align with federal definitions from the outset. “Definitions within our student information system are aligned to the federal definitions, for example, first-time, full-time student,” one agency explained. At the same time, another said, “As part of our state catalog of data definitions, we default to adopting the IPEDS definition as our state definition, when available.” This reliance on IPEDS definitions, one participant observed, helps prevent “interpretational drift,” ensuring that metrics retain consistent meaning across agencies and over time.

Several respondents also noted that IPEDS serves as a validation mechanism for state data. By comparing state-calculated aggregates with IPEDS-reported figures, agencies can identify discrepancies that point to reporting errors or definitional inconsistencies. “When our internal enrollment numbers differ from IPEDS, it prompts a review on both sides. It helps us improve data quality,” one respondent explained. This validation process strengthens both datasets and bolsters confidence in public-facing reports.

“When our internal enrollment numbers differ from IPEDS, it prompts a review on both sides. It helps us improve data quality.”

In addition, about two-thirds of agencies reported using IPEDS data for strategic planning (68 percent), research and policy analysis (68 percent), and legislative reporting (65 percent). As one respondent noted, “The Board office responds to a number of legislative requests on behalf of the universities that are only possible with IPEDS data.” Another explained, “Many mandatory state reports rely on IPEDS data, definitions, and guidance, including reports for enrollment, graduation rates, and outcomes.” Smaller but notable shares cited its use for state benchmarking (48 percent), performance accountability metrics (45 percent), public-facing dashboards (42 percent), and internal-facing dashboards (39 percent). In comparison, 36 percent said they use it to

support state budgeting and statutory reporting, and 23 percent use it to inform funding models.

Figure 2. Uses of IPEDS Data by State Higher Education Agencies

Percent of responding agencies citing each use of IPEDS data

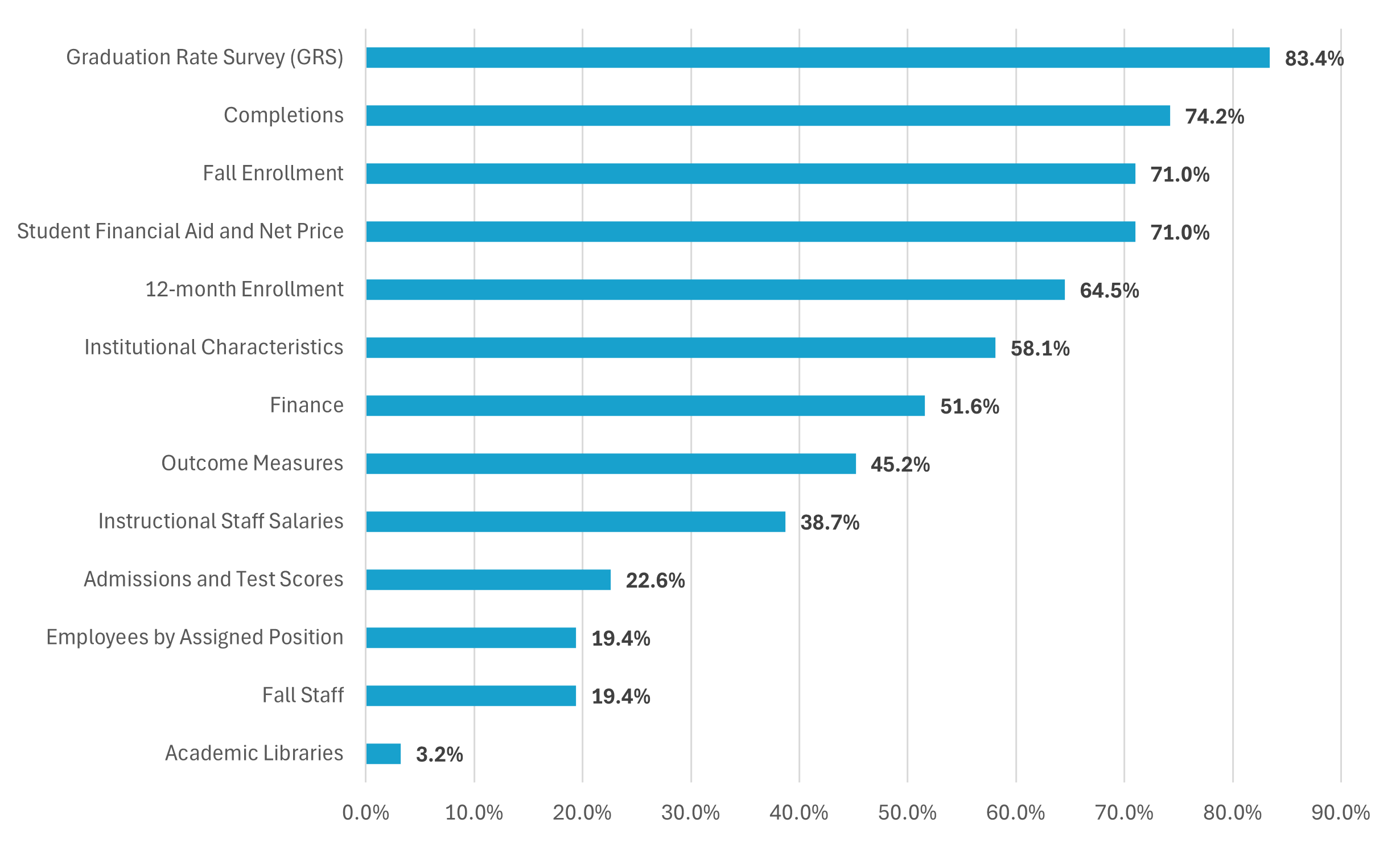

Key IPEDS components used by state agencies

In addition to these broad functions, survey responses reveal which specific IPEDS survey components are used most frequently (see Figure 3). Graduation rates (83 percent) and Completions (74 percent) are the most common, followed closely by Student Financial Aid and Net Price (71 percent) and Fall Enrollment (71 percent). Over half of responding agencies also rely on 12-month Enrollment (64 percent), Institutional Characteristics (58 percent), and Finance data (51 percent). Moderate shares use Outcome Measures (45 percent) and Instructional Staff Salaries (38 percent), while fewer cited Admissions and Test Scores (22 percent), Fall Staff (19 percent), or Employees by Assigned Position (19 percent). Only one respondent (3 percent) reported using Academic Libraries data.[6]

These results indicate that IPEDS data related to student outcomes, completions, and affordability are the most essential for users, while staffing and library data are the least commonly referenced. Respondents emphasized the centrality of these outcome metrics, both in how IPEDS defines certain measures as well as the data itself, to accountability and policy work

Figure 3. Most Commonly Used IPEDS Survey Components

Percent of responding agencies using each IPEDS component

Policy applications: funding, accountability, and transparency

Building on these foundational uses, many state agencies incorporate IPEDS data directly into their funding, accountability, and transparency frameworks. Nearly half (48 percent of responding agencies) indicated that IPEDS metrics are used in funding or performance-accountability systems. Commonly referenced indicators include graduation and retention rates, completions, and net price.

One respondent explained, “We utilize IPEDS data as a critical component to our annual appropriation request justification to the legislature.” Another described how IPEDS data directly inform tuition and financial aid policy, noting that “we use IPEDS data in our analysis to make recommendations for public institutions on their tuition and fee setting, which ultimately impacts how much state financial aid programs can cover costs (influencing award schedules) and impacts how much revenue an institution can reasonably expect, which impacts how they spend their state appropriation.” A third agency noted that “our campuses receive performance funding from the state legislature. Key metrics include completion and graduation rates that largely follow IPEDS data definition and calculation.” Still another reported, “We follow IPEDS definitions for graduation and success rates, which are critical metrics for institutions to measure outcomes and accountability.”

“We use IPEDS data in our analysis to make recommendations for public institutions on their tuition and fee setting, which ultimately impacts how much state financial aid programs can cover costs (influencing award schedules) and impacts how much revenue an institution can reasonably expect, which impacts how they spend their state appropriation.”

In some states, IPEDS data are referenced or embedded in statute or policy. One agency reported that “IPEDS tuition and fee definitions are written into statute and used in return-on-investment calculations tied to funding models.” Another noted that “IPEDS percentile rankings for graduation and retention rates determine whether institutions qualify to offer certain advanced degree programs.” A third example is from a state agency that reported, “IPEDS data are used in six of the performance indicators: Average Net Price at Public Institutions, Undergraduate Enrollment, Graduation Rate (150 percent of normal time), Graduation Rate (200 percent of normal time), Number of Degrees/Certificates, and Retention Rate.” Eleven responding state agencies reported that they are aware of state statutes that would be directly affected if IPEDS data were no longer available. Because few state agencies have conducted comprehensive reviews of their statutory frameworks, this number likely understates the full extent of legal dependencies on IPEDS definitions and reporting.

Transparency and public communication also feature prominently in how state agencies report IPEDS data usage. Thirty-nine percent of responding agencies reported using IPEDS to populate public dashboards or annual reports. As one interviewee described, “Our state dashboard imports IPEDS completion and enrollment figures so users can view every institution, public or private, in one place.” Another respondent emphasized that IPEDS’ comprehensive coverage of Title IV institutions, including private and proprietary sectors, allows state agencies to present a complete and comparable view of higher education: “We load IPEDS series into our warehouse and feed them into public dashboards so students and families can see side-by-side comparisons.”

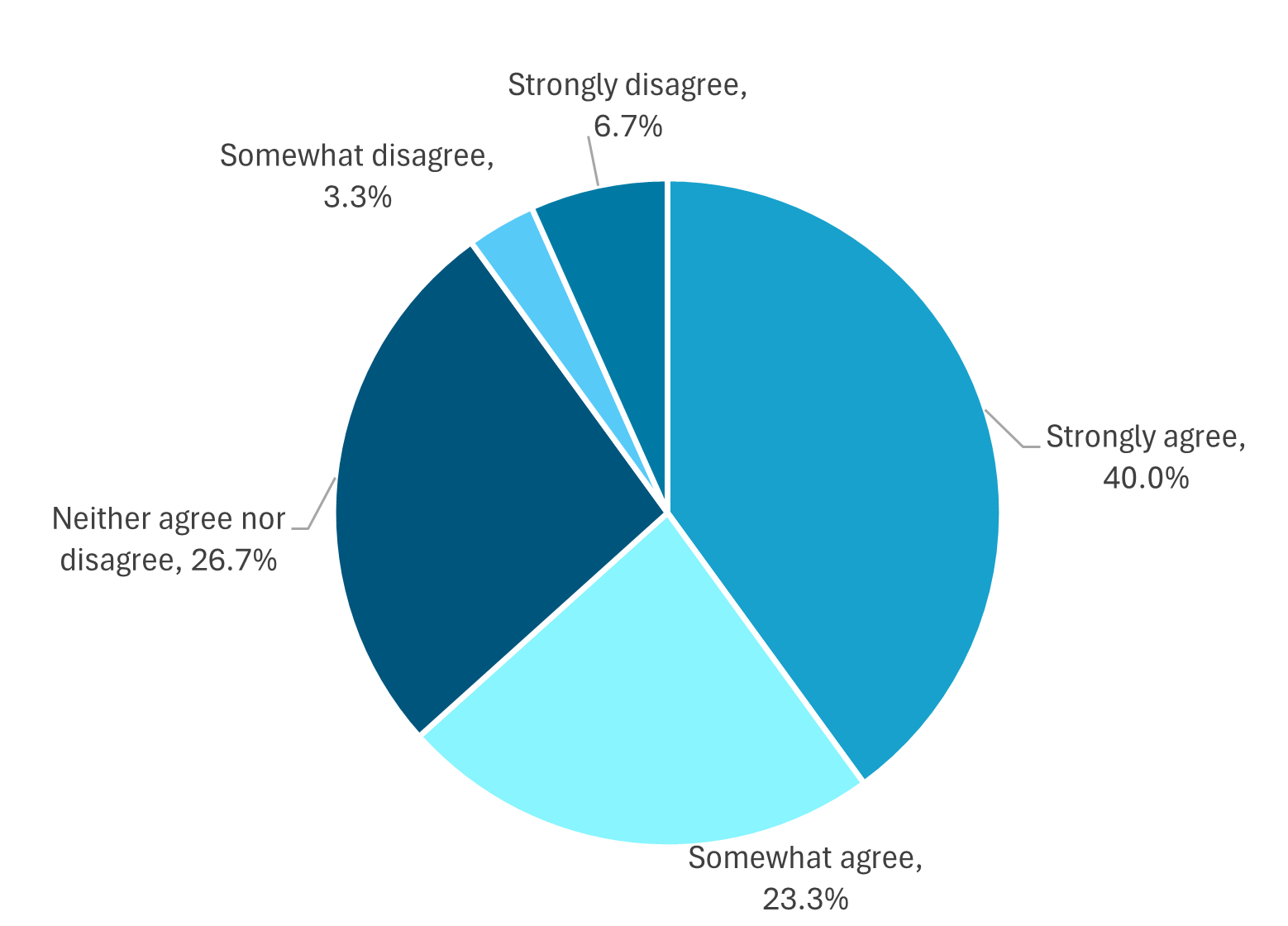

When asked to rate the usefulness of IPEDS data for public-facing dashboards, most respondents expressed positive views. As shown in Figure 4, about two-thirds of responding agencies (63 percent) either strongly (40 percent) or somewhat agree (23 percent) that IPEDS data are useful for providing information to students, families, and the public. Roughly one-quarter (27 percent) were neutral, while only a small minority somewhat disagree (3 percent) or strongly disagree (7 percent).

Figure 4. Agreement That IPEDS Data Are Useful for Public-Facing Dashboards

Percent of responding state agencies indicating each level of agreement

Respondents noted that state agencies rely on IPEDS to fill critical data gaps in areas where they lack their own collections. One respondent explained, “We currently do not collect data on faculty to student ratios, staff and faculty headcounts, staff and faculty salaries, and institutional finances…so we are relying heavily on IPEDS data.” Others noted that IPEDS’ inclusion of independent and proprietary institutions enables state agencies to analyze access, completion, and affordability across all sectors. As one state agency leader observed, without IPEDS, “states would lack the complete picture needed to analyze enrollment, outcomes, and costs consistently across institutions.”

Finally, responding state agencies mentioned that the credibility and transparency of IPEDS data make them helpful when communicating with legislators, boards, and the public. Because IPEDS is a known, publicly available source, the data carries authority and minimizes disputes over methodology or interpretation. In policy environments where confidence in data is essential, IPEDS provides what one respondent called “a shared, verifiable foundation for decision-making.”

Integration with state data systems

Many state agencies have taken steps to integrate IPEDS data directly into their internal systems, ensuring consistency between state and federal datasets. This integration ranges from importing full IPEDS files into data warehouses to linking selected indicators to student-level data within state longitudinal systems.

Respondents explained that this integration not only streamlines reporting but also strengthens data quality and validation. As described earlier, IPEDS comparisons also help agencies verify the accuracy of their own data collections. These collaborative checks, respondents noted, enhance the reliability of both federal and state datasets.

These practices demonstrate how IPEDS complements, rather than duplicates, state data collections, providing a stable national reference that supports interoperability and validation between data sources. As states continue to modernize their data infrastructure, this alignment between IPEDS and state systems forms a critical foundation for the overall national postsecondary education data infrastructure.

Common challenges in using IPEDS

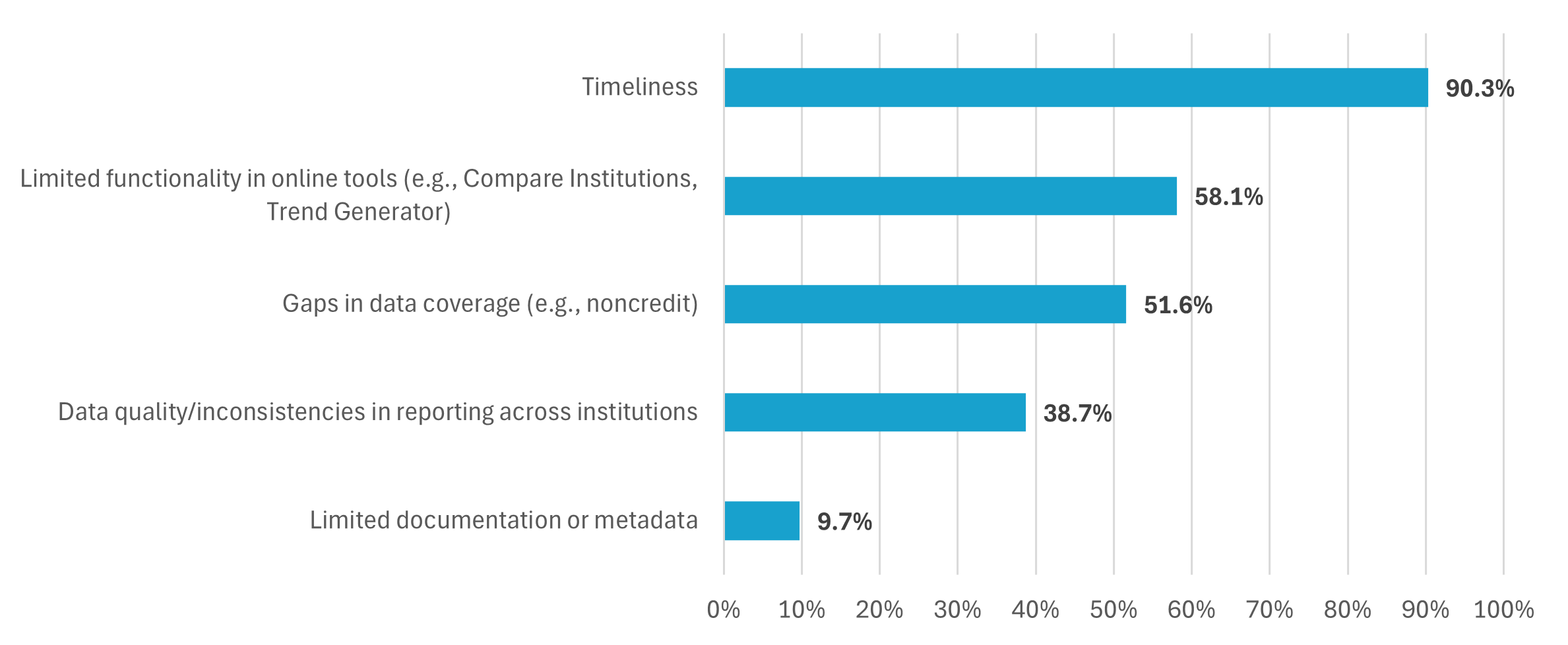

Although overall perceptions of IPEDS were positive, most respondents (90 percent) identified timeliness as a challenge (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Challenges Reported by Responding State Agencies

Percent of responding state agencies identifying each challenge

Respondents explained that while IPEDS provides indispensable context for national and cross-state comparisons, the data are often not available quickly enough to inform real-time policy or legislative decisions. As one participant explained, “When I need up-to-date information, I use internal or state data. But to illustrate to policymakers how our state compares to others, we need the multi-state reach of IPEDS.” Another noted that “the two-year lag makes it hard to demonstrate institutional change to legislators.”

A number of respondents described how the current release cycle, which they cite can range from 12 to 18 months after data collection, limits the IPEDS data’s usefulness for state policy and accountability work. Some proposed shorter turnaround times, such as three to six months, or the release of preliminary data prior to full validation, to provide earlier access to state agencies while maintaining data quality. At the same time, others cautioned that timeliness should not outweigh accuracy. One data officer explained, “Accuracy can’t be rushed. IPEDS has a delay, yes, and it is a challenge, yes, but should the data be rushed to be more timely? No. We simply caveat [that] the IPEDS data are for the prior year and work with the best available data.” Another felt that, “There’s likely no way to speed it up without significantly sacrificing data quality. However, the data from IPEDS is notably lagging.”

Fifty-eight percent of responding agencies also cited limited functionality in IPEDS public tools as a barrier to effective use. While the underlying data are highly valued, respondents noted that extracting and analyzing them can be cumbersome without proper training or staff capacity.

Forty-eight percent of responding state agencies reported that gaps in data coverage present a challenge, particularly around noncredit and sub-baccalaureate programs where IPEDS data are limited. Respondents explained that these gaps hinder states’ ability to fully understand student pathways and workforce alignment. State agencies emphasized the need for more detailed and timely reporting on short-term credentials, transfer activity, and adult learners, all of which play a growing role in state policy priorities.

Finally, 39 percent of responding agencies cited data-quality and consistency issues, including differences in institutional reporting practices that sometimes lead to anomalies or missing data. A small number (about 10 percent) also mentioned difficulties related to limited documentation or metadata, noting that clearer, consolidated metadata and more consistent variable definitions could further improve usability.

Priorities for improving IPEDS

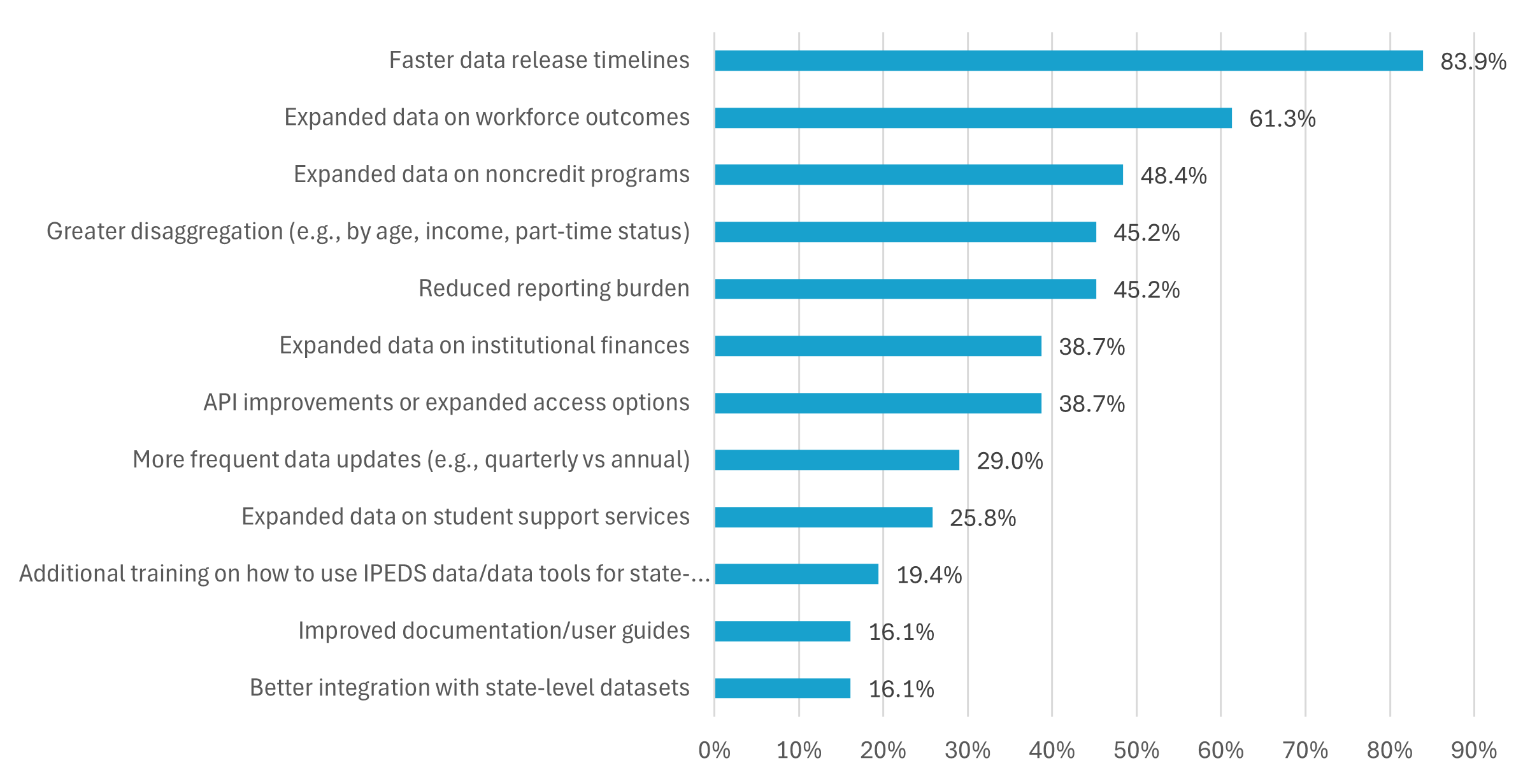

In addition to describing current uses and challenges, respondents were asked to identify priorities for improving IPEDS data (see Figure 6). The results show strong agreement around the need for faster data release timelines, cited by 84 percent of responding agencies, followed by interest in expanded data on workforce outcomes (61 percent) and noncredit programs (48 percent). Roughly half of respondents pointed to the need for greater demographic and programmatic disaggregation (45 percent), and a reduced reporting burden (45 percent).

Other priorities included API improvements and expanded data-access options (39 percent), expanded data on institutional finances (39 percent), and more frequent data updates (29 percent). Smaller shares cited better integration with state-level datasets (16 percent), improved documentation or user guides (16 percent), and additional training on how to use IPEDS data and tools for state-level analysis (19 percent).

Figure 6. State Agency Priorities for Improvements to IPEDS Data

Percent of responding agencies selecting each improvement priority

State agency preparations and preparedness for possible disruptions to IPEDS

Recent uncertainty about the stability of the federal postsecondary education data infrastructure has prompted concern among state agencies about the continuity of IPEDS operations. Reports of disruptions to staffing and data releases at NCES have raised questions about the long-term stability and resourcing of the system.[7] Because state agencies depend on IPEDS, any disruption could create additional challenges for agencies and fragment the national postsecondary education data infrastructure that links states, institutions, and the federal government.

Against this backdrop, the survey asked state agencies to assess both their preparedness for a potential disruption in IPEDS data or tools and whether they have made any changes to their data strategies in anticipation of such an event.

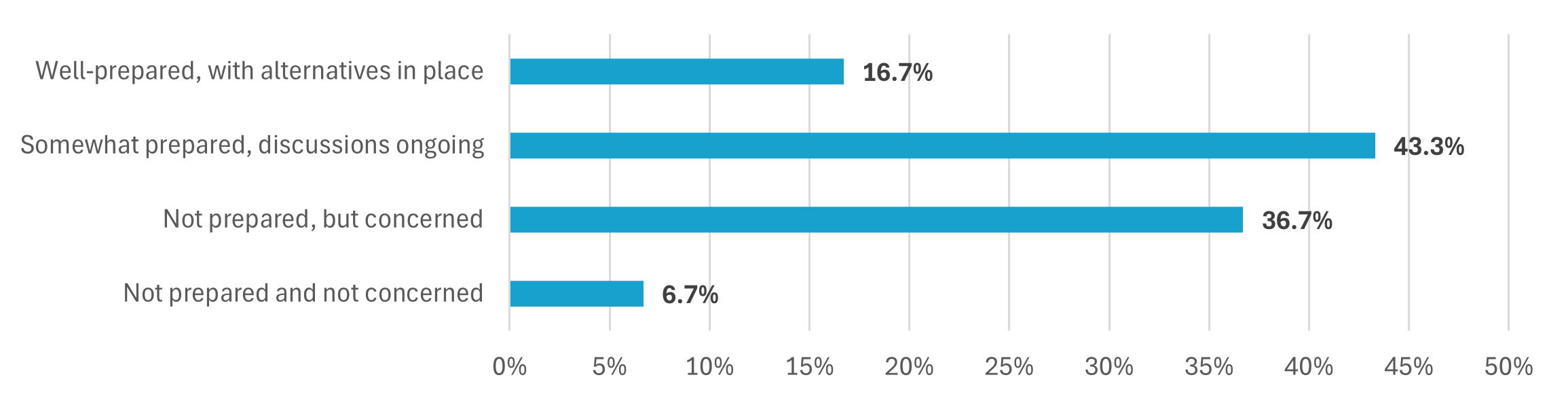

As shown in Figure 7, most agencies expressed at least some concern about their ability to manage a major disruption in IPEDS data availability or quality. Over one-third (37 percent) said they are not prepared but concerned, while 43 percent reported being somewhat prepared, with internal discussions underway. A smaller share (17 percent) indicated that they are well prepared, having developed or identified alternative data sources. Only 7 percent said they are not prepared and not concerned.

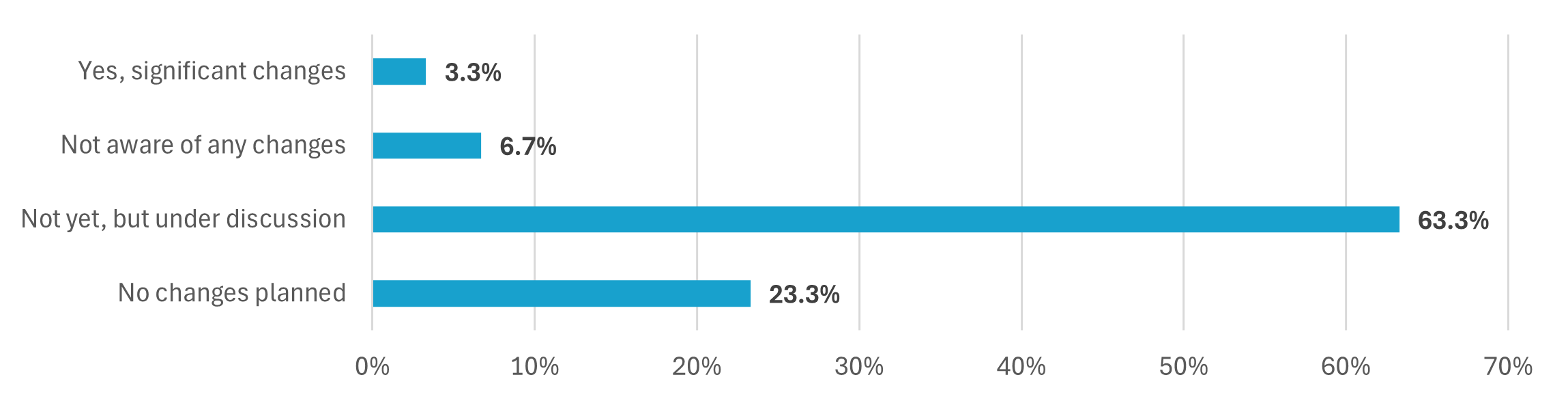

Respondents were also asked whether their agencies have made or discussed any changes to their data strategies in anticipation of possible disruptions to IPEDS, such as reduced staffing or support at NCES. As shown in Figure 8, nearly two-thirds (63 percent) said such changes are under discussion but have not yet been implemented. Another 23 percent said no changes are planned, and 7 percent said they were not aware of any changes. Only 3 percent reported that their agency had already made significant changes.

Among state agencies that have begun planning or implementation, the most common action reported was increasing reliance on state-collected data (34 percent). Twenty-eight percent reported forming or expanding data-sharing partnerships, 16 percent built or enhanced internal unit-record systems, and 13 percent acquired or evaluated commercial datasets.

In interviews, respondents described these efforts as precautionary, intended to ensure continuity of essential indicators should federal processes slow or priorities shift. One interviewee described this approach as “a way to make our system a little more resilient without drifting from IPEDS definitions.”

Figure 7. Preparedness for Potential Disruptions to IPEDS Data or Tools

Percent of responding state agencies selecting each response option when asked how prepared they are for potential disruptions to IPEDS

Figure 8. Changes to State Agency Data Strategies in Anticipation of Potential Disruptions to IPEDS

Percent of responding state agencies selecting each response option when asked whether they have made changes in anticipation of potential IPEDS disruptions

Similar concerns have been reported nationally by institutions that are also highly reliant on IPEDS data. A 2025 survey by the Association for Institutional Research (AIR) found that institutional research professionals across the country are evaluating potential risks associated with changes in the NCES operations and their impact on federal data systems.[8] These parallel findings suggest that both state agencies and higher education institutions are taking measured steps to safeguard data continuity in an evolving federal environment.

Discussion

Several themes emerge from the interview and survey results.

The interdependence of state and federal data systems

The findings point to an interconnected relationship between state postsecondary data systems and federal data systems. These state systems rely on IPEDS for institutional context, standardized definitions, and national benchmarks. IPEDS data also serve as a way to check state data, helping agencies identify discrepancies and improve accuracy.

This interdependence means that disruptions at the federal level, such as delays in data releases or staffing challenges at NCES, can impact state reporting and policy timelines. Strengthening IPEDS should therefore be understood not only as a federal priority but as an investment in the coherence of the national postsecondary education data ecosystem.

Balancing timeliness and quality

Respondents emphasized that delays in data releases limit IPEDS’ usefulness for near-term policy decisions but also recognized that accuracy and consistency remain essential. These perspectives highlight a persistent tension: agencies require timely information to support legislative and budget cycles but also depend on IPEDS’ data review process to ensure reliability. Addressing this tension will require coordinated efforts that maintain accuracy while improving the predictability of data releases.

Federal capacity and coordination

This study was conducted during a period of uncertainty about the stability of federal postsecondary education data systems. The Inside Higher Ed article on staffing reductions and delayed data releases at NCES in 2025 underscore the vulnerability of the infrastructure that supports IPEDS.[9] Respondents shared related concerns. Survey results indicate that few agencies have comprehensive contingency plans in place, though discussions about preparedness are occurring across many states.

These findings indicate that state systems cannot easily substitute for IPEDS if access or quality were compromised. The data infrastructure provided by IPEDS provides a single national framework that supports comparability and reduces duplication across states. Without it, the postsecondary education data landscape could risk becoming fragmented, with state agencies relying on distinct definitions, reporting cycles, and standards.

Maintaining NCES capacity to sustain IPEDS operations is therefore essential to preserving the comparability and quality of postsecondary education data nationwide. Continued investment in staffing, modernization, and collaboration between federal and state agencies will help improve timeliness, maintain quality, and ensure the stability of the system over time.

Conclusion

The survey and interviews show that IPEDS remains a key component of the national postsecondary education data infrastructure. IPEDS plays an important role in how states collect, align, and communicate postsecondary education data. At the same time, the findings highlight certain challenges with the current data collection and dissemination structure that limit its usefulness for some state purposes. Timeliness, level of detail, and ease of access remain persistent challenges. State agencies described relying on their own data systems when rapid or highly disaggregated information is needed. Still, they continue to look to IPEDS for nationally consistent data definitions and indicators that carry credibility in policy discussions. Addressing these issues will require careful coordination between federal and state partners, as well as higher education institutions, to improve data release schedules and expand access without compromising quality.

The study also reveals the extent to which states are exposed to federal data disruptions. Although some agencies are developing contingency plans, most remain dependent on IPEDS as an authoritative source for core institutional data measures. Recent instability at NCES underscores the importance of maintaining federal capacity to sustain IPEDS operations and communication. The stability of IPEDS is therefore important not only for federal purposes but also for the work of state agencies.

To continue to grow its usefulness to state agencies, IPEDS should focus on improving timeliness, expanding data disaggregation, and strengthening interoperability with state systems. Achieving these goals will depend on continued coordination among federal and state agencies and their staff, as well as sustained investment in the infrastructure and staffing that make this nationally shared resource valuable.

Endnotes

- Emma Johnson, “‘Gutted’ NCES Releases First Batch of Higher Ed Data,” Inside Higher Ed, September 25, 2025, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/faculty-issues/research/2025/09/25/gutted-nces-releases-first-batch-higher-ed-data. ↑

- Higher Education Act of 1965, P.L. 89–329, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/COMPS-765/pdf/COMPS-765.pdf. For more information on the history and evolution of the IPEDS data collection, see Elise S. Miller and Jessica M. Shedd, “The History and Evolution of IPEDS,” New Directions for Institutional Research 2019, no. 181 (2019): 47–58, https://doi.org/10.1002/ir.20297. ↑

- Referred to as “state agencies” in this report, this term comprises state postsecondary governing boards, coordinating boards, and departments of education, and systems composed of two- and four-year and technical institutions. ↑

- Carrie Klein and Jessica Colorado, “Strong Foundations 2023: The State of State Postsecondary Data Systems,” State Higher Education Executive Officers Association (SHEEO), Boulder, CO: SHEEO, 2024. Available at: https://postsecondarydata.sheeo.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/SF2023Report.pdf ↑

- Institute for Higher Education Policy (IHEP), “The Case for IES: Four Ways States Use Federal Data to Guide Postsecondary Research and Policy,” Washington, DC: IHEP, 2025, https://www.ihep.org/the-case-for-ies-four-ways-states-use-federal-data-to-guide-postsecondary-research-and-policy/. ↑

- This survey question was based on the data files available at the time of the survey rather than the data that are currently being collected. The Academic Libraries survey was discontinued in IPEDS beginning in the 2025-26 data collection cycle. ↑

- Emma Johnson, “‘Gutted’ NCES Releases First Batch of Higher Ed Data,” Inside Higher Ed, September 25, 2025, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/faculty-issues/research/2025/09/25/gutted-nces-releases-first-batch-higher-ed-data. ↑

- Association for Institutional Research (AIR), “Impact of Changes to U.S. Department of Education Operations: Results of the 2025 AIR Community Survey,” Tallahassee, FL: AIR, 2025. Available at: https://www.airweb.org/docs/default-source/documents-for-pages/community-surveys/air-impact-of-changes-to-us-doe.pdf?sfvrsn=5cb127d4_2 ↑

- Emma Johnson, “‘Gutted’ NCES Releases First Batch of Higher Ed Data,” Inside Higher Ed, September 25, 2025, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/faculty-issues/research/2025/09/25/gutted-nces-releases-first-batch-higher-ed-data. ↑