US Faculty Survey 2018 Reveals Uncertainty about Fraudulent Research Practices

A report published earlier this year from The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine disclosed findings from their recent assessment of reproducibility and replicability across different fields of research. Congress requested this collaborative study because of prolific media exposure on data misconduct and the inability of scientists to replicate important research. Additionally, there has been extensive media coverage of researchers who fabricate their data and have published fraudulent findings. Due to this abundance of concern regarding research fraud and data fabrication in diverse fields, as well as feedback from various academic communities, the 2018 cycle of the US Faculty Survey included new inquiries to assess faculty attitudes on this topic.

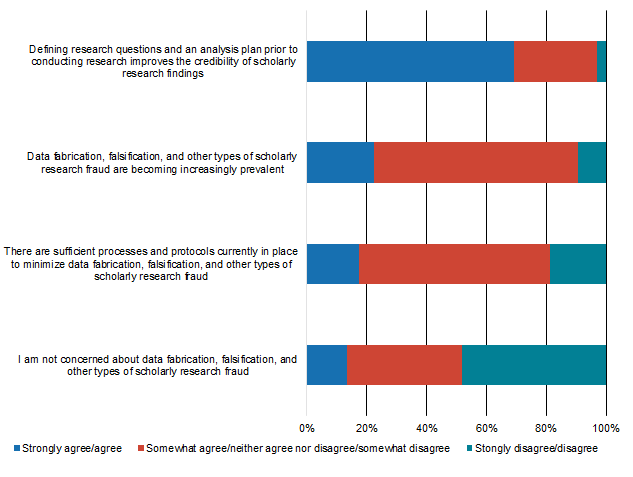

Forty-eight percent of the survey’s 10,919 respondents are currently concerned about data fabrication, falsification, and other types of research fraud. But it’s not clear that this is a new concern, as the vast majority of faculty (68 percent) are not sure if these faulty practices are becoming increasingly prevalent (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Please read the following statements and indicate the degree to which you agree or disagree with each. This question was only displayed to respondents who indicated they build up or collect data for their own research.

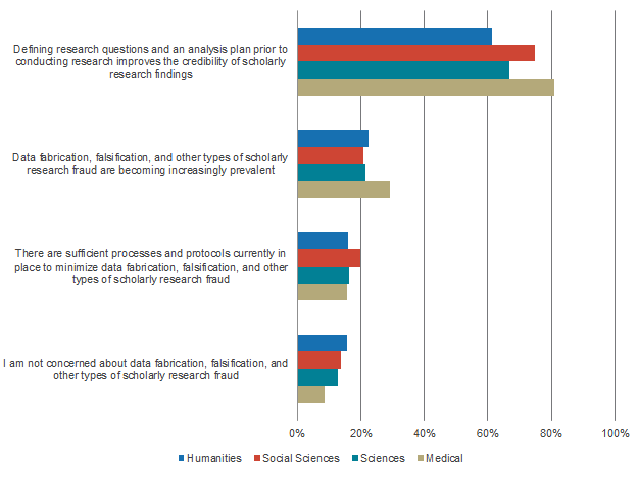

What may be alarming is the degree to which medical faculty agree that these practices are becoming increasingly prevalent compared to their colleagues in other disciplines (see Figure 2). Medical faculty are also particularly less likely than their colleagues in other disciplines to agree that they are not concerned about these faulty practices. This notable difference between medical faculty and their peers prompts further investigation.

Figure 2. Please read the following statements and indicate the degree to which you agree or disagree with each. Percent of respondents that strongly agree/agree with each statement.

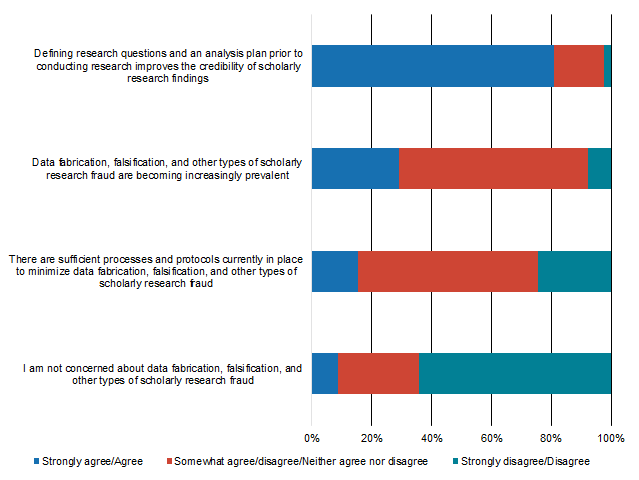

Roughly two-thirds of the 398 medical faculty members who completed the survey are concerned about data fabrication, falsification, and other types of scholarly fraud (see Figure 3). Medical faculty are more concerned about these issues than other faculty, as roughly 51 percent of scientists, 45 percent of social scientists, and 44 percent of humanists are concerned about data fraud and fabrication. Additionally, about three in ten medical faculty members agree or strongly agree that these practices are becoming increasingly prevalent, notably higher than about two in ten faculty members from other disciplines.

Figure 3. Please read the following statements and indicate the degree to which you agree or disagree with each. Percent of medical faculty respondents.

Possible Solutions

Given that medical faculty are somewhat more concerned than their colleagues in other disciplines that these practices are increasing, and about six in ten are unsure if there are sufficient protocols in place to prevent these practices, what do our survey data reveal about possible solutions to these perceived issues? One possible way of reducing potential research fraud and fabrication is the dissemination of completed datasets for study replication. About six in ten medical faculty members strongly agree that it is important for other researchers to organize and deposit their datasets so that others can attempt to replicate their findings. However, only 27 percent of medical faculty think it is worth their time to organize and develop such documentation.

Another possible way of mitigating issues of data fraud and fabrication would be to define research questions and analysis plans prior to conducting research. Eight in ten medical faculty members agree or strongly agree that using this method improves the credibility of scholarly research findings. While the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine concur that researchers should define and explain their research questions and methodology, they also posit that researchers should more often explain any uncertainties within their results, cautiously use statistical inference tools such as the p-value, and take effect sizes and generalizability into consideration when assessing reliability and reproducibility. However, the degree to which these approaches can be implemented within fields outside of science and medical fields may be limited; our survey findings show, for example, that humanists are relatively less likely to see the establishment of research questions and analysis plans as a solution to potential data fraud and fabrication practices (see Figure 2).

What’s Next for S+R?

As this was the first survey cycle which assessed faculty attitudes on this topic, we will have to look to 2021 to determine if concern over these faulty scholarly practices will change. We are also in the process of developing a series of projects that will explore other angles of this issue. In the spring we will launch projects in collaboration with academic libraries on teaching with data in the social sciences and conducting research with big data. And, we are currently in the process of developing a project in collaboration with academic libraries to explore research support needs for psychology scholars, which will provide a deep divide into discipline-specific perceptions and practices related to reproducibility and working with data. If you have any interest in being involved in these projects, please reach out to Danielle Cooper (danielle.cooper@ithaka.org).