Magnitude and Bond

A Field Study on Black Literary Arts Organizations

Foreword

By Lisa Willis, Executive Director, Cave Canem

[…] we are each other’s

harvest:

we are each other’s

business:

we are each other’s

magnitude and bond.

Gwendolyn Brooks – Paul Robeson[1]

Poets are our witnesses and documentarians of the historical and ongoing struggles of the Black American experience. Thus, it is without coincidence that a poetry organization is at the forefront of interrogating the enduring and centuries old question, how have we continued to survive? The collective uplift Magnitude and Bond seeks to enable is central to Cave Canem’s mission and work. While it is no secret that the literary field at large operates among conditions of relative scarcity and financial precarity, these conditions are exacerbated by structural racism and inequality, making the survival of Black literary arts organizations especially difficult within an already challenging field.

Despite the systemic and concentric disparities and a lack of external institutional support, Black literary arts organizations continue to have a profound influence on the literary landscape. The idea of “Black art” as something that is a phenomenon, a source of entertainment, and separate from the American cultural canon has resulted in structural inequities and unsafe spaces for our participation in the written word, amongst other creative practices, the vestiges of which continue to this day.

The Reconstruction Amendments, enacted after the Civil War, marked a pivotal turning point for Black Americans.[2] By guaranteeing legal access to education, these amendments not only empowered individuals but also signaled the genesis of Black literary arts organizations, and their collective activism. These organizations, as noted by Gholnescar E. Muhammad in “The Literacy Development and Practices within African American Literary Societies,” served as collaborative spaces used to construct knowledge and engage each other to become literate…they had wider goals of benefiting the conditions of African Americans and the wider society.”[3] Historically and today, Black literary arts organizing has maintained critical spaces for writers, nurturing writers and providing marginalized communities with models for self-organization and cultural preservation.

Charles McKinney, a civil rights movement scholar at Rhodes College in Tennessee, noted “there’s a whole bunch of grass-roots Black organizations that no longer exist, and that’s because they did not have access to resources—they could not expand, they could not pay staff, they could not engage in the deep work.”[4]

While this study does not encompass all such organizations, the collective efforts represented here span over 140 years of dedication to Black writers. In 2021, a gathering of five Black literary organizations collectively known as Getting Word: Black Literature for Black Liberation was convened to call attention to the existence and important role of Black literary organizations in creating safe spaces, providing professional cultivation, and investing in artistic cultivation for our communities. These organizations have played a crucial role in promoting the written word within the Black community, enriching American culture, and transforming lives. We honor the legacy of our elders and the shared work of organizations, societies, clubs, and movements that continue the tradition of spreading access to the written word in our community by acknowledging their names as part of this report.

To date, there has been no holistic assessment to discern and document the strategies and tactics employed by literary arts service organizations serving communities of color. Research into the challenges faced by Black literary arts organizations is crucial for addressing the cyclical ongoing issues of underfunding and underappreciation. By filling knowledge gaps and providing actionable insights, this research can offer valuable guidance to these organizations and contribute to building a more sustainable literary ecosystem. The tools and resources developed through such research can be utilized by other organizations navigating similar economic and social challenges.

The urgency to champion Black literary arts is never ending. Magnitude and Bond encourages a change that recognizes and embraces the fundamental role of Black literature and seeks to ensure the longevity of Black literary arts organizations for generations to come.

In the absence of action without urgency, may the loss of us not be the price.

We are each other’s business. We are each other’s magnitude and bond.

Introduction

Black literary arts organizations nurture literary talent, establish living literary canons, and generate thriving communities of artists and readers, cultivating Black spaces for sharing the vulnerable processes necessary to invent new ways of saying important things. They carry forward a legacy of global renown. They also face significant resource constraints, which force creative adaptations, and, in some cases, threaten their continuity. This report, which explores the sustainability of Black literary arts organizations, grew out of a research process undertaken through a partnership between Cave Canem and Ithaka S+R.[5] It explores the characteristics of Black literary arts organizations, the challenges they face, and the adaptive strategies they employ to secure their future and maintain thriving artistic communities. More specifically, the report studies members of Getting Word: Black Literature for Black Liberation (hereafter referred to as the Collective).[6] This Collective includes a foundation for Black literature, a publishing platform for Black writers and artists, an academic center for Black poetry, and two poetry-oriented literary service non-profit organizations.

In order to produce this research, Ithaka S+R collaborated closely with a working group, composed of directors from the Collective, as well as two experts in the literary field, to hone our research questions and instruments. With their input, we conducted a survey of the members of the Collective to gather institutional data on topics including revenues, expenses, governance structure, and strategic plans. Following the survey, we interviewed 19 individuals, including directors of the participating organizations, board members, audience members, community members who have participated in programming, experts in the literary field, and staff.[7] To focus our inquiry we developed four research questions, which we shared with the working group early in the process. These questions guided the entire research process:

- What are the adaptive strategies, systems, or practices that allow Black literary service organizations to succeed in spite of conditions challenging their survival?

- What are the major barriers or challenges to Black literary service organizations’ achieving sustainability relative to the broader literary arts field and the broader cultural sector?

- What are the characteristics of Black literary arts organizations (e.g., funding models, history, impact, founding call, proximity to hegemonic culture, cultural context, organizational or leadership structures, networks, engagement strategies, and community practices)?

- What financial tools, as well as non-fiscal resources and networks, are employed by nonprofit literary service organizations to operate within adverse economic conditions?

The survey and interviews generated a comparative understanding of the financial and operational realities of the organizations that are part of the Collective. Findings have been organized into the following thematic topics:

- Resilience and legacy

- Leadership and planning

- Operations

- Programming

Based on our analysis of the survey results, a synthesis of the interview transcripts, and supplemental desk research, this report provides a snapshot of Black literary arts organizations as they work towards maintaining their presence and meeting the needs of their constituencies. Magnitude and Bond is written for multiple audiences: first, for Black arts administrators, artists, and audiences who can benefit from learning from their peers, and second, for funders, current or potential donors, or anyone who is interested in learning how to contribute to the sustainability of these organizations.[8] Each section concludes with a description of a need in the field, which may be of interest to foundations and donors, as well as a recommendation geared toward organizational leaders.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the members of the working group and the literary experts for their support and guidance in the development of the project and this research report, listed in alphabetical order by last name:

Working Group Members:

Khadijah Ali-Coleman- Former Executive Director of The Hurston/Wright Foundation

Lauren K. Alleyne- Executive Director of Furious Flower Poetry Center

Duriel E. Harris- Editor in Chief of Obsidian: Literature & Arts in the African Diaspora

Nichelle M. Hayes- Interim Executive Director of The Hurston/Wright Foundation

Candace G. Wiley- Executive Director of The Watering Hole Poetry Org.

Lisa Willis- Executive Director of Cave Canem; and Principal Investigator

Literary Experts:

Herman Beavers- Professor of English and Africana Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, and Cave Canem fellow

Shelagh Patterson- Magnitude and Bond Project Manager, Lecturer Doctoral Schedule at Medgar Evers College-CUNY, and Cave Canem fellow

Additionally, we are grateful for the contributions from The Wallace Foundation, particularly Mina Matlon for her guidance throughout the project, as well as support from Alaka Wali and Carlton Turner. We also thank Flower Effect, specifically, Ashley Johnson, for the guided sessions available throughout the project.

Resilience and Legacy

In some ways, it is a misnomer to apply the term “sustainability,” in the traditional sense of the word, to Black literary arts organizations. These organizations do not resemble traditional nonprofit cultural organizations. As we will see in later sections, they have persisted through adverse conditions with scarce resources. In fact, the durability of these organizations lies in the reality that they are able to continue existing, in many cases, without substantial foundation support, revenue, or competitive salaries, but with a consistent commitment to excellence that drives leaders in this field. This contrasts with the broader nonprofit cultural and education sectors, where staff navigate a competitive and relatively liquid labor market and leaders command substantial salaries.[9] While multi-million dollar operations, such as Corcoran Gallery of Art ($67 million of revenue in 2012),[10] Concordia College in New York ($46 million of revenue in 2020),[11] or University of the Arts ($100 million of revenue in 2023),[12] can be shuttered because of fiscal challenges, Black literary arts organizations have learned to grow on less than one percent of those revenues. While much of this report will explore how to secure resources for growth and stability, we point as well to the important lessons to be learned from the resilience of the Collective, their peer organizations, and the legacy of the Black literary arts that preceded them.

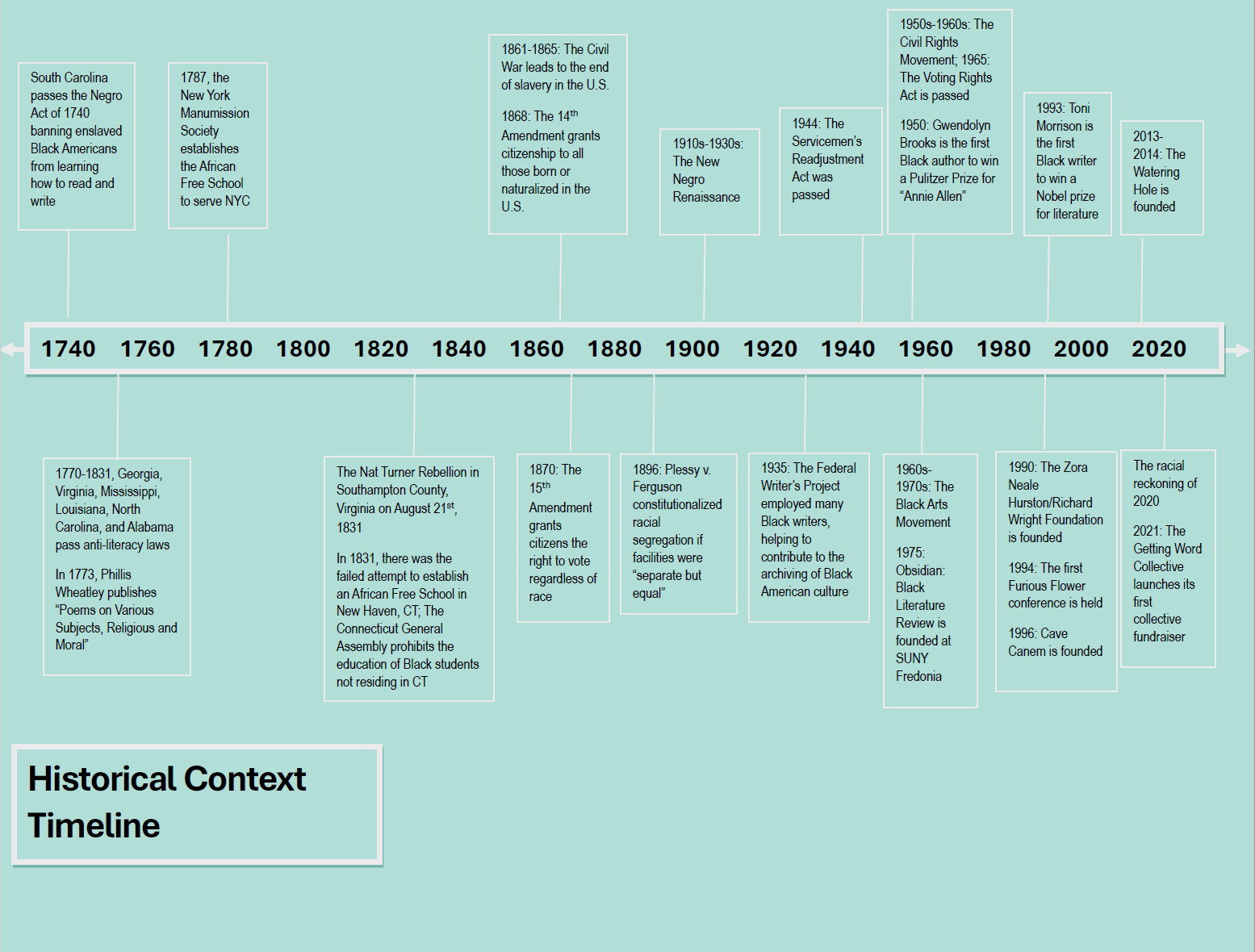

It is necessary to reflect on the legacy of literacy restrictions imposed on Black Americans in the 18th and 19th centuries and the history of resistance, organized in part through Black literary societies and movements. This section will briefly discuss that timeline and share details of the origins of each of the organizations in the Collective.[13]

Historical and Social Context[14]

The history of legal barriers to literacy for Black people in the United States generated a wave of organized resistance through Black literary societies and organizations dating back to the 18th century.[15] Beginning in 1740, with South Carolina’s “Negro Act,” anti-literacy laws were passed to prevent both enslaved and free Black Americans from learning how to read or write.[16] The law read: “All and every person and persons whatsoever, who shall hereafter teach, or cause any slave or slaves to be taught to write, or shall use or employ any slave as a scribe in any manner of writing whatsoever, hereafter taught to write, every such person and persons shall, for every such offense, forfeit the sum of one hundred pounds current money.”[17] The law was designed to prevent Black people from full participation in the public sphere as equal citizens.

Seven out of the 11 Confederate states upheld official laws barring Black literacy, until the end of the Civil War.[18] These ethnically specific anti- literacy laws were created in order to maintain racial hierarchies.[19] Black literacy was seen as a direct threat to the foundation of slavery, and preserving illiteracy justified theories of inequality between races.[20]

Fewer legal restrictions existed in the North allowing for some early Black authors to publish their work, as shown with poet Phillis Wheatley’s first major publication in 1773. However, social prejudice persisted, limiting the acceptance of impressive literary achievements. And Wheatley’s success was short-lived, as she struggled to continue to have her talent recognized by the publishing industry.[21] Of Wheatley, Thomas Jefferson stated, “Religion indeed has produced a Phyllis Whatley [sic]; but it could not produce a poet. The compositions published under her name are below the dignity of criticism.”[22] Dismissing Black literary achievements functioned as a way to categorize Black intellect as inferior to white authors, therefore maintaining a racial hierarchy.

The establishment of the New York Manumission Society’s African Free School in 1787 was a major step toward providing education.[23] However, the example of Prudence Crandall reveals how racist social norms could be codified into law. Crandall opened a private school for girls in Canterbury, Connecticut in 1831, and in 1832 admitted a Black woman who wanted to be a teacher.[24] Parents withdrew their children from the school. Crandall made it the mission of the school to educate Black students and began actively recruiting Black students regionally. As a result, the Connecticut General Assembly passed a law prohibiting the education of Black students who did not reside in Connecticut.[25] Crandall was tried and found guilty of violating the law. She was fined and the school was shut down. Upon appeal, the ruling was overturned by the Connecticut Supreme Court on a technicality, and the school was allowed to reopen. However, it faced continued opposition from members of the local white community and was eventually attacked by a mob and forced to close. In 1886, Crandall was officially honored as a “state heroine” by Connecticut, and the Prudence Crandall House was recognized as a National Historic Landmark.

More frequently, hegemonic resistance to Black education in the North was managed socially rather than legislatively. Fear of educating the Black population skyrocketed throughout white communities prior to the Civil War due to the Nat Turner Rebellion in Virginia in 1831. Nat Turner, an educated Black man, was used as an alarmist example of what could happen when Black people, enslaved or free, were educated.[26] In response to Nat Turner’s Rebellion, there were a growing number of reported instances of protests, petitions, and violence against Black Americans in Northern states, in attempts to further undermine Black education.[27]

During this time, Black communities began establishing literary societies.[28] Between 1828 and 1846, at least 56 active literary groups were created to disseminate knowledge and promote the literary arts. Many Black Americans began to create their own private libraries and made their collections available to others.[29]

The New Negro Renaissance[30]

The New Negro Renaissance of the 1920s reshaped the landscape of American culture, particularly American literature.[31] This era of American literature was fueled by the Great Migration, which saw over five million Black people move from southern states to northern ones, seeking relief from Jim Crow laws.[32] Places like Harlem, Chicago, and Washington DC became havens for Black intellectuals, artists, and writers to openly express themselves. Figures like Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Claude McKay, and Jean Toomer became central voices of the movement. Black-led literary journals emerged, including The Crisis, The Crusader Magazine, and Fire!!: A Quarterly Devoted to the Younger Negro Artists.

The New Negro Renaissance extended beyond the borders of the United States, influencing the global perception of Black culture and laying the groundwork for future civil rights activism. This period also saw the rise of Black-owned publishing houses, theaters, and magazines, which provided platforms for Black voices that had long been silenced or sidelined.

Langston Hughes considered the 1936 Hollywood film Green Pastures to represent the end of this movement, which he criticized for its stereotypical and demeaning portrayal of Black life and spirituality. To Hughes, Green Pastures, based on a play depicting biblical stories through the lens of a southern Black church, represented a backward step from the progressive vision of Black culture that the Renaissance had championed. Hughes believed that the film, widely popular among white audiences, reinforced outdated and simplistic views of Black people rather than reflecting the complexities, intellectual advancements, and cultural richness that the New Negro movement had strived to promote.[33]

HBCUs and the GI Bill

The majority of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) originated during the period following the Civil War and were established to provide higher education to Black Americans who were systematically excluded from predominantly white institutions (PWI).[34] Many HBCUs were founded through the support of religious organizations, philanthropic efforts, and the Freedmen’s Bureau, with the mission to educate newly emancipated Black citizens and prepare them for professional careers.[35] Howard University, founded in 1867 in Washington, DC, and Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University), established in Alabama in 1881 by Booker T. Washington, became cornerstones of Black higher education.

The passage of the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly known as the GI Bill, dramatically impacted enrollment at HBCUs. The bill provided returning World War II veterans with access to higher education, offering tuition and living stipends that opened the doors of colleges and universities to millions of Americans.[36] For Black veterans, HBCUs became essential institutions where they could take advantage of these educational benefits, as many PWIs continued to practice segregation or limit their admissions of Black students.[37] This led to a significant surge in enrollment at HBCUs. Following the war, overall enrollment at colleges and universities increased by 13 percent, but enrollment at HBCUs expanded by 26 percent.[38] Despite these advances, Black veterans faced persistent challenges under the GI Bill, including discriminatory practices that limited their access to loans and housing benefits, and, in some cases, denied them the full educational benefits they were entitled to. Amid these challenges, the GI Bill helped cultivate a new generation of Black literary talent.

Black Arts Movement

The Black Arts movement was catalyzed by the work of poet and playwright Amiri Baraka, who played a pivotal role in its inception.[39] In 1965, following the assassination of Malcolm X, Baraka established the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School (BARTS) in Harlem, which became a hub for Black creativity and expression. Key literary figures of the movement included poets like Sonia Sanchez, Nikki Giovanni, and Haki Madhubuti. Playwrights such as Ed Bullins and Larry Neal also contributed significantly, laying the groundwork for the later works of August Wilson.[40] The Black Arts Movement also led to the establishment of Black-owned publishing houses, literary journals, and bookstores, which provided crucial platforms for emerging Black writers.[41] The 1967 Black Writers conference, organized by John Oliver Killens, at Fisk University catalyzed the movement, particularly inspiring Gwendolyn Brooks to write more directly about Black identity and collective action.

In 1975, Ntozake Shange delivered a speech at Howard University that critiqued the artistic direction of Black writers during the height of the Black Arts Movement.[42] In her speech, Shange questioned why so many Black writers were creating works that sounded alike, adhering to a consistent ideology, which she thought lacked space for feminist perspectives. This led to an expansion of Black women writers, including Alice Walker, Margaret Walker, Gayl Jones, and Mari Evans, whose styles differed from those of the Black Arts Movement, paving the way for Toni Morrison’s arrival on the literary stage in the 1970s and 80s.[43] These writers generated a new thread in the tradition of Black literature, diverging from the Black Arts Movement and bringing new layers of identity into the fold, including feminist themes and personal narratives.

Formation of the Getting Word Collective

The Black literary landscape above, while incomplete, offers some historical guideposts to give context to the Collective. Specific details of the origins of the Getting Word Collective have been included in their organizational profiles, which are included in Appendix A.

In 2020, Cave Canem initiated the historic collaboration, collectively known as Getting Word: Black Literature for Liberation, among five Black literary arts organizations: Cave Canem, Furious Flower Poetry Center, The Hurston/Wright Foundation, Obsidian: Literature & Arts in the African Diaspora and The Watering Hole. The collective was formed as a proactive response to the increased calls for social justice in 2020 and support of Black owned and led businesses, with a goal to raise awareness of and call for the long-term monetary support of Black literary arts organizations.

The Collective has met monthly since 2021. Cave Canem serves as the fiscal sponsor and lead administrator for the annual appeal and contributes staffing to facilitate the administrative and communications work involved, including a social media toolkit and messaging. The Collective has a partnership with Bookshop, which for the past several years has served as the lead contributor to the campaign and allows for a portion of books sold from their collective booklist to benefit the campaign. Funds are equally distributed across the organizations in the Collective. The group also shares donor information and insights.

The formation of the Collective creates a natural scoping mechanism to study a subset of Black literary arts organizations that are collaborating in order to support one another’s future sustainability. The following sections share findings based on the evidence gathered throughout this research project.

Leadership and Planning

In the course of surveying and interviewing leaders of the Collective and their various constituencies, findings calcified around three primary topics: leadership and planning, programming, and operations. This section explores leadership and planning, focusing on the following themes: expertise, strategic planning, tenure and compensation, and succession planning.

Domain and Operational Expertise

As part of the survey, directors of the Collective were asked to report on their own expertise, as well as the expertise of board members. The categories of expertise types developed by the researchers included domain expertise, connections within the literary community, strategic planning, publishing expertise, fundraising, managerial expertise, convening expertise, legal expertise, and financial management. This question was asked in order to gain an understanding of the organization’s strengths, as well as to identify gaps in expertise that could impact the organization’s sustainability. Respondents were asked to choose all areas of expertise that apply for both themselves and their board. The results showed that these leaders hold important forms of expertise that are essential for developing audiences and community engagement, but that they have gaps in certain operational areas.

Survey respondents reported a high level of domain expertise in the literary arts, literary history, comparative literature, writing pedagogy, Black studies, and related subjects. Four out of five directors selected domain expertise, and three out of five directors selected “connections with the literary community.” Four out of five directors also reported that their board members have domain expertise, as well as connections with the literary community. Through interviews with members of each organization’s audience, it was clear that high levels of domain expertise helped to strengthen the legitimacy of each organization’s place in the community.

Survey respondents less frequently selected financial management, legal expertise, managerial expertise, and fundraising as their area of expertise. Survey results showed a connection between fundraising expertise and revenue. Even given the demonstrated value that domain expertise has within the context of running literary arts organizations, operational expertise is essential for many aspects of organizational sustainability. However, obtaining operational expertise is a sensitive process for these organizations, to some degree by design. Some share the perspective that “best practices” for organizational growth have been defined by primarily white institutions. Leaders in this field see their organizations as developing and persisting in antithesis to traditional institution-building.

Strategic Planning

Three of the organizations in the Collective reported experience with strategic planning and were each in different stages of strategic plan development. Interviewees expressed some wariness towards the strategic planning process: “Well, strategic plans are useful, but from an artistic point of view, they’re also limiting because you have to focus on a certain set of objectives,” said one interviewee. Another said, “I think if you haven’t done a strategic plan, you should do one. You can call it something else if you like. Let’s get away from all these corporate words.” A strategic plan can have an effect of locking an organization into a set of goals, preventing them from being responsive to shifting needs of their communities, particularly if it is designed without intentional flexibility. In exchange, the organization gets something that can be very useful towards its sustainability. One director told us how they leverage the strategic plan during fundraising: “One way I have been approaching funders is to say, ‘Yes, I feel confident in our budget at least through the next five to six years,'” thanks to the budget planning exercises that the organization undertook as part of their strategic planning process. They then are able to use the strategic plan to structure requests for funds, a process that has yielded some success, possibly because it is a language familiar to foundations.

But strategic plans are not only useful for external fundraising. They can help with generating alignment among staff, informing decision making in cases that otherwise might be unclear. As one interviewee said, “On a day- to-day basis, having a strategic plan means aligning the work that we do with those stated objectives. Figuring out how to put in place policies that support those goals.” One of the policy outcomes of the strategic plan included creating a minimum payment for poets who are invited to read at events presented by the organization. This has further resulted in a policy for partnering with other cultural organizations: “When other organizations want to collaborate with us, we tell them that we will not collaborate with them unless they are offering this minimum fee to the artists that they’re inviting. In certain cases, we have had to decline collaborations if poets were being offered fees that are lower than our minimum fee.” It is possible such a policy might have emerged ad hoc, but a strategic plan empowers staff to propose such policies within the context of stated organizational goals.

Hallie Hobson, one of our interviewees who consults for both large and small cultural organizations, recommended beginning this process with an organizational assessment (including financial analysis) to understand where the organization has been, what it has accomplished, and what resources were needed to achieve those accomplishments, as well as the challenges and barriers they have navigated.[44] Following this, she recommends conducting a visioning exercise—to articulate the answers to questions such as:

- Where do we want to go?

- Have the needs of the field or their constituents stayed the same or changed?

- Have there been constraints to delivering the mission?

- Are there opportunities to take advantage of?

- Is there a need to contract and refocus the mission?

- Has our purpose been fulfilled and they want to wind down?

- Do we have goals for expansion, new programming?

- Do we want to hold steady?[45]

In Hobson’s view, many organizations misunderstand the creation of a strategic plan as the end of the process. Instead, she says, this is where the work begins: “To construct a considered, planful, measured path from where we have been to where do we want to go.” Hobson emphasizes realistically acknowledging that it takes time, expertise, planning, money to chart a new path and that typically it will require incremental scaling (or incremental contraction) to get to the goal in an achievable, operationally feasible, and financially sustainable way. The best type of strategic plan is an orienting framework that allows for flexibility and responsiveness, promoting creativity in near-term decision making in order to bring the organization closer to a long-term goal.

Tenure and Compensation

The ability to run an organization on a shoestring budget requires a level of grit and adaptability that many in the wider cultural sector could learn from. It also means that work often goes uncompensated or under- compensated. Two of the directors in the Collective serve their roles in a volunteer capacity or have other arrangements with their host institutions like course reassignments. Three of the directors work a second job.

Directors frequently expressed concerns about relying on volunteer labor, but it is difficult to address that issue when there are no funds to pay leadership. One director noted that their idea of success would be to make their role as director a full-time position.

For some organizations, such as those housed in academic settings, employee salaries are funded by their host institutions and/or through grant funding. One director explained that “I think the reason we are in a good position financially is because I haven’t raised my salary.” Others expressed that while they are grateful for the support from these academic host institutions, funding cuts are a constant threat that are out of their control.

These types of financial threats extend beyond organizational sustainability. Chronic uncertainty can also impact the health of the directors and staff who are running the organizations.[46] This is especially concerning given the degree of key person risk that these organizations face. While a number of directors have had a long tenure in these roles, some have experienced leadership changes every few years. One interviewee explained that leadership turnover is a threat to the sustainability of these organizations. “I think leadership is really difficult to keep in these spaces. It’s a burnout space and it really requires a dedicated individual. Many of us are making sacrifices to be here.”

Succession Planning and Governance

Leadership turnover is one of the most disruptive challenges an organization can face. It is particularly threatening to an organization’s continuity if a succession plan is not in place. Academic centers in other fields have demonstrated the impact the departure of a founder or leader can have. For instance, the Poverty Center at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill had to significantly scale back their operations,[47] and The Center for Public Integrity at the University of Missouri had to close when their founders stepped down.[48] None of the directors of the Collective reported having succession plans at the time of the survey administration. In some cases, this was due to limitations from governance structures or the executive director’s capacity levels due to resource constraints.

The governance structure of an organization can also play a large role in securing—or threatening—the continuity of the organization. Each member of the Collective reported having a governing board, with some boards specifically focused on policy, and others as advisors. Members of the Collective housed in universities have access to certain elements of organizational infrastructure that have been established by their host institution. But these can be contingent on university policy and bureaucratic processes that are out of the literary arts organization’s control.

Field Need: Strategic planning and succession planning

Foundations making grants to organizations such as those in the Collective may not believe that the applicant has demonstrated a sufficient level of planning to receive a grant. In such cases, it would be helpful for foundations to facilitate some of the planning necessary to communicate a vision for impact, continuity, and resource allocation.[49] They could do this either by making program staff available, or by maintaining a consultant on retainer who can help to guide these processes. Funders should consider providing capacity building funds, allowing organizations to engage in planning activities that are aligned with the organization’s culture. Such efforts might be prompted by a grant application, and result in the necessary documents to secure funding. The outcomes should be beneficial to the organizations regardless of success with the application.

Recommendation: Seek staff members to fill gaps in expertise

Directors should develop a further assessment of organizational needs alongside a self assessment of capacity and expertise, particularly when it comes to professionalized operations for nonprofit administration, such as legal expertise, financial expertise, managerial expertise and fundraising expertise. Directors should strategically seek to gain expertise that cannot be outsourced, and recruit professionals who can meet the need of the space and help fill in the gaps. This is likely to result in scenarios where leaders should prioritize professional skills over domain relevance when operational expertise is needed. Directors should also consider recruiting board members from organizations that may be of strategic benefit, for instance from university administration.

Programming

One of the ways we can characterize the organizations that compose the Collective is through the programmatic offerings they provide. That is, what types of events can audiences attend with them, or what kinds of outputs can the organizations acquire from their audiences? Table 1 tallies the number of organizations in the Collective that offer each type of program.

| Programming | Number of Organizations |

| Workshops | 5 |

| Publications | 5 |

| Professional Development | 4 |

| Retreats | 3 |

| Conferences | 3 |

| Grants | 2 |

| Courses | 2 |

As Table 1 shows, most programming efforts are centered around workshops and publications, reflecting a strong commitment to nurturing literary development. Organizations in the Collective reported a distinctive focus on multiple types of literacies, incorporating a variety of forms of expression into the writing process, including music, dance, vernacular writing, among others. All organizations surveyed identified the primary communities they serve as encompassing both virtual and in-person audiences, with an additional focus on other literary arts organizations, writers, and vulnerable populations.[50] This section will offer reflections on the impact these programs have had based on conversations with audiences and community members.

Community Feedback on Programmatic Offerings

In the course of our interviews we heard from audience members and community members about what they valued in relation to programming, as well as what kinds of barriers prevented them from participating in literary programming. One theme that emerged was the importance of access. Access can often mean practical considerations such as accessibility by public transportation, offering options for virtual programming, timing an event so people can attend after work, and marketing an event sufficiently in advance in order to give people a chance to plan. We also heard that choosing to attend an event often depends on who the writers are, or what the subject of the workshop is, with some interviewees expressing an interest in interdisciplinary or experimental premises for workshops. As one described,

We may be talking about form, or it may be just a reading, but how can there be some aspect of the event that’s different or innovative, that pulls me in and feels instructional. As an audience member who’s engaging with literary institutions, you have some interest in literature, either as a writer or as a lover of literature, and you want to deepen that relationship in some way. Do these events feel in any way instructional? Even if it’s just a reading, how am I going to walk away with something different, something that I didn’t come into the room with that will enrich my practice?

Perhaps because there is often a blurry line between audiences who practice writing and those attending events as purely readers or appreciators of literature, it’s likely that craft-oriented programming appeals to a wide range of audiences who want to understand the writing process, as well as enjoy the end product. This interviewee went on to share that they are happy to pay for workshops, in person or virtual, in which the participant is getting face time and there is a high level of engagement. They would also pay to attend a lecture, but in that case they would need for the speaker to be someone with some name recognition and whose writing they respected. However, they would be less likely to pay for this type of event if held virtually. While these findings are anecdotal, they point toward some interesting opportunities for future market research, wherein a broader audience-focused survey could help organizational leaders make informed decisions about future programmatic efforts.

Virtual Engagement Strategy

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many of the organizations in the Collective underwent a process similar to the rest of the cultural sector and shifted towards virtual programming. In doing so, some organizations in the Collective reported that they discovered new global audiences who were highly engaged with their programs, a rare silver lining of those times. One of the persistent challenges cultural leaders now face is how to nurture these new virtual communities. Leaders across the cultural sector as well as in the Collective are not sure what the goals should be for these audiences. Do they exist in parallel to the primary in-person programming of the organization, or are they a pathway to greater in-person engagement? Below are reflections from one director who is grappling with this question:

COVID really normalized virtual engagement. And so as we’ve been trying to move into in-person spaces, we actually have more people asking where’s the virtual version? Do I have to show up? Or: ‘I’m not going to be able to make it. Can I have the recording?’ We don’t necessarily always have the capacity to do both. It’s either or. So if we’re going to do virtual, we worry about recidivism with our students. We are trying to figure out what are the ways that people are returning? In this new world, we are trying to discover what is a way that we can exist and sustain our offerings that have been successful and then broaden them to meet the expectations of our communities.

This passage raises some interesting questions about programmatic strategy in relation to in-person and virtual experiences. If the goals are to maintain a virtual community in parallel to the in-person communities that they foster, that will require a strategy that emphasizes breadth of engagement and the technology and skills to broadcast in-person events virtually. If the goal is to use virtual programming as a pathway towards growing in-person events, it will require a strategy that focuses on virtual engagement as a stepping stone towards in-person engagement, rather than as an end in itself.

Horizontal Community Building

A consistent theme that emerged from the interviews was the degree of reverence that audiences and community members had for their experiences with these organizations. Consider this passage from a retreat fellow:

It’s an intense experience, similar to going to camp or even college, where you’re on site with a new group of people. You’re living, eating, breathing together the whole time. I carpooled to the campus with some other poets, some of whom had been there before. The first night they say, ‘You have to write a poem by 10AM the next day.’ Then, on the next day, you have to do the same thing. And then the next day, you have to do the same thing. I think it’s five days of writing completely new poems. In the evening you’re connecting with other poets. There are readings that you can sign up to do. In the mornings, you’re writing. There are craft lessons that both faculty and fellows will lead. There’s a field trip day to a nearby city. For me, I feel like the relationships that I made with people, they’re people who I love, they’re my close, close friends. There’s something about horizontal community building. That’s the secret sauce. We are meeting each other and supporting each other and growing alongside each other for the rest of our lives. Beyond that, the faculty are incredible. These are the people you would wish to work with. I mean, it’s pretty astounding.

They use the term “horizontal community building” to describe the connections made at the retreat.[51] The term applied to a number of other testimonials offered in the interview process as the “secret sauce” that makes audiences so supportive of organizations in the Collective. The description of the retreat is emblematic of both the enthusiasm for programming and transformative experiences that community members report from engagements with the Collective. Another audience member described the pleasure of encountering familiar faces when attending readings or workshops, “I don’t think I’ve ever gone to an event organized by any of these organizations and not have known someone there.” Beginning to recognize familiar faces, they began to take their writing practice more seriously. They could see that their community was growing: “It’s a signal that you are practicing your craft when you begin to see a community emerging around your practice of its own accord.” These statements support the idea that poetry organizations offer a valuable element to the writing process, supporting the human need for connection and shared experience, through developing a community of practice.[52] It is therefore useful for literary arts organizations and their funders to think about a significant component of their value proposition as cultivating experiences for their communities, alongside developing a canon, facilitating publishing, and other aspects of the literature production process.

Audiences and community members recognize the events they attend as professionally and personally meaningful, even life changing. This suggests that a major role of literary arts organizations is fostering connections and providing opportunities for writers and audiences to have shared experiences. One of the experts we interviewed thought there might be an opportunity for the Collective to expand towards a literary festival: “Something like that would take a real investment of funds. But could you raise money to do that? I think there very well might be a foundation that thinks that this is an exceptional idea and would be interested to see a festival emerge. The idea is that we’re going to give you a version of our content, but in a live setting, for the Getting Word Collective it’s a little different programmatically, but it’s a good idea.”

Of course, such an effort would require significant planning and sensitivity to preserve the atmosphere that has allowed for the aforementioned transformative experiences to emerge. But the results could be quite beneficial, enabling connections with new literary audiences and at the same time raising the profile of organizations in the Collective. Enabling virtual access to a festival like this could draw large global audiences, revealing new revenue streams. A good starting point towards testing this theory would include an evaluation of the decennial Furious Flower poetry conference, which serves as a major live Black literary event.

Field Need: Expand experience-based offerings

Members of the Collective have an opportunity to collaboratively develop an event celebrating Black literary arts in a festival-like setting, leveraging the impactful experiences they cultivate among their audiences. While audience demand for such an expansion is evident, funding has not been identified to unlock these opportunities. With great care towards preserving authenticity and avoiding excessive commercialization, such an event could draw new forms of revenue, between philanthropy, corporate sponsorships, individual donors, and event revenue.

Recommendation: Study audiences and create virtual access points

If leaders are unsure what their goals are with relation to virtual engagement strategies, it may be helpful to gather information from their communities in order to learn about their expectations, limitations, and goals. Anecdotal evidence gathered points to an opportunity to conduct a wider audience evaluation, which could inform efforts to secure funding for expanded programming. It is possible to seek funding opportunities to conduct research for a cohort of organizations that have similar aims. As one of the directors grappling with this question speculated, there could be new donors who become available by investing more in virtual programming, with the possibility of reaching new audiences.

Operations

To better understand the adaptive strategies employed and the barriers that have confronted the Collective, this section explores the operations of the organizations within the Collective, both in terms of capital and labor. To do this, it is useful to situate the organizations within a broader landscape of cultural organizations, and explore the differences in funding, staffing, and organizational strategies. For instance, the organizations in the Collective are a subset of the Black literary arts, which is to say a culturally specific subset of the broader field of the literary arts.[53] These organizations operate within the expansive cultural sector in the United States, balancing revenues from foundations, federal grants, individual donors, and program-based revenue. The cultural sector in the US, while robust in certain resources, does not enjoy anything comparable to the state support that is provided in other high GDP nations, whether sorted by gross GDP or per capita.[54] The United States does, however, enjoy unparalleled resources in charitable giving, with roughly half a trillion dollars in giving annually (compared to, for example, the UK which gives under ten precent of that figure per year).[55] About five percent of that domestic giving figure, $25 billion, is administered to arts and culture. Much of this philanthropy supports the eight or nine figure budgets of large museums and performing arts centers, which have comparatively well-staffed development departments and deep relationships with foundations.[56] The literary arts collectively receive “peanuts” in comparison.[57] Culturally specific subsets of the literary arts field are perhaps the most operationally precarious types of arts organizations one can find.

This is out of sync with the historical contributions that these types of organizations nurture, as has been explored earlier in this report. Nevertheless, it is within this context that the Collective, and those that came before, have cultivated and shepherded literary talent, maintaining and innovating on a tradition that has enriched the literary canon and the lives of readers around the world. One professional in the field put it this way: “There are thousands of nonprofit theaters, thousands of dance companies. And when we look at the literary arts field, it’s much, much smaller. When you look at organizations that are actually out there raising money, there aren’t many. In fact, during Covid we distributed funds to smaller organizations, and when we looked at the total budget, for the 400 groups or so that applied from the literary arts field, their total combined budget was less than the total budget for MoMA. The entire literary field can fit in one visual arts museum. The Black literary arts are an even smaller subset.” They went on to point out that even if the raw materials needed to produce the art are less expensive than other disciplines, the project of running a literary arts organization, creating programming, generating publications, and maintaining a public presence is no less challenging.

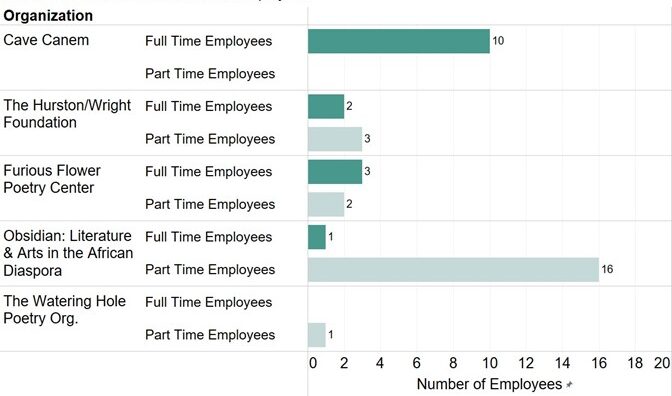

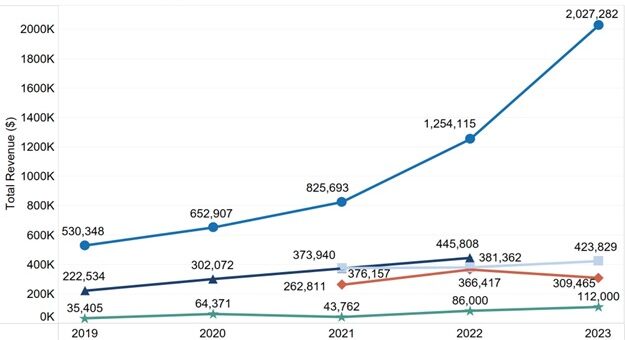

This distinction is also true in the context of culturally specific institutions. Figures 1 and 2 provide context for the size for the organizations in the Collective, as well as a snapshot of their revenue over the last five years. This information was obtained by asking leaders of the Collective to provide current staffing numbers, as well as supplementary information to publicly available financial data.

Leaders of each organization were asked to report their current staff numbers for full-time and part-time employees. As shown in Figure 1, in aggregate, the majority of staff working in these organizations within the Collective are part-time employees, and there are only a handful of full- time staff members. Many of these organizations rely on their part-time workers as well as volunteer labor to operate.

Figure 1: Staff Numbers for the Collective

Using publicly available financial forms, like 990s, as well as working closely with leaders of the Collective, Figure 2 shows the total revenue of each organization, where available, from 2019-2023. While Cave Canem is an outlier in terms of total yearly revenue in comparison to other members, this graph shows that the majority of the organizations in the Collective continue to operate on a yearly budget of less than $500,000.

Figure 2: Total Annual Revenue (2019-2023) for the Collective[58]

As one of our interviewees put it, “Poetry is largely free, which makes it one of the most democratic and accessible art forms, granting it an incredible public reach.” It is indeed one of the distinguishing characteristics of the discipline; while there are always events to throw and books to sell, the reality is that many poems can be read for free in a browser. As this interviewee suggested, this can create sustainability challenges when it comes to generating sufficient revenues to maintain a literary arts or literary service organization: “For the most part, you don’t have substantial revenue coming from ticket sales or book sales. The number of poets who make a living from book royalties and book sales is very, very, small.” Similarly, a leader in the Collective expressed that in her experience, many people adjacent to the field believe that these organizations can run on “fumes and good intentions,” when in fact, few people outside the organizations have an understanding of the pressure that resource constraints place on them. Another director expanded on this point when asked about maximizing value from existing assets, describing that, “The organization has not been stable enough to implement recommendations offered by the advisory board member who has fundraising expertise. Limited funding equates to limited staffing, which equates to limited capacity to effectively maximize community resources and extend reach.”

Strategies for Managing Foundation Relations

Further analysis of the revenue models for members of the Collective showed that funds from individual donors tend to be used for general operations, while funds from grants are more likely to be used to support specific programs, such as reading series, workshops, online courses, retreats, or printing books. The challenge with this budget structure is that individual donors typically support a much smaller portion of the budget than grants. This means that the type of revenue the organization makes can influence how it is staffed, or whether it can invest in assets like, for instance, owning the property from which the organization operates.

One director described that their strategy for addressing this imbalance is to address their organization’s needs directly with program officers at every available opportunity. They shared that organizations facing this revenue bind need to be able to use grant funds for general operating costs, and that multi-year grants can enable stability in the organization, especially if there is transparency about their duration and likelihood to be renewed. “We’re not just submitting an application. There is a lot of dialogue and case-making that’s going into it,” they said of their process, which has been highly effective thus far.

This strategy is reflective of an ongoing critique of both foundations and federal grantmaking in the cultural and nonprofit sectors.[59] Previous research has shown that nonprofits often underreport their true overhead costs on tax forms and in fundraising materials due to pressure to conform to funder expectations. This cycle of misleading reporting and unrealistic expectations leads to underinvestment in necessary infrastructure, which ultimately impacts the effectiveness of the organization and the services they provide.[60]

In the case of the Collective, this particular director transparently tells funders that, since they don’t have a large development team, it is important to seek multi-year general operating grants. “That’s one less grant I have to rewrite next year. I have to make that case and build awareness of what it means to fund a space like ours.” In response, they found the message was well-received by several funders, “They’ve told us, you don’t have to apply again. We’re just going to repeat the same grant and add it to the existing grant. We hear you about the paperwork and the processing. We’re going to eliminate that.” When making this case, it’s important to have budget numbers projected out for several years, they said. This creates a sense of security for the funder, that the organization is stable enough to benefit from the resources. “From what I’ve seen, the funding field has really been very responsive to that type of transparency, case-making and advanced budgeting. They come to understand why you’re asking for this large amount, because it’s actually part of a sustainability tactic, and not just that we’re setting ourselves up to only be existing on one grant.” This can create a virtuous circle, where “funding attracts funding,” they said. By setting goals, organizing finances, and making the case for grants that cover general operating expenses, an organization benefits both from the strategic planning that this process requires, and from the increased likelihood of receiving funding as a result. Critically, this process requires multiple conversations and iteration with funders, rather than a cold application submission.

Beyond Operations

One of the directors in the working group who works a day job in real estate has made it a goal to buy a building to operate from in 2025. They described their vision to us: “I want us to have a building with multiple levels. I want there to be a public space downstairs and a yoga studio. I want to rent apartments and commercial spaces out to fund the operations and subsidize spaces for artists. I want this whole building to operate as an art space where regular people are supporting the arts and the organization every month. That’s what I want.” This vision has been written into the organization’s strategic plan and would make them a sustainable part of the local arts ecosystem. Funders should consider strategies that help organizations raise capital towards accruing assets, such as real estate, which can both contribute to the financial security of an organization and simultaneously create programming spaces that enrich the local cultural landscape.[61] However, such opportunities are dependent on the organizational type, as well as location. In some cases, owning an office space can create unexpected financial vulnerabilities for nonprofits who then have to include those costs as overhead.

One interviewee who runs a Black literary journal described how they were struggling to secure funding through philanthropic arts programs, speculating that many of these types of programs are not sure whether a journal falls within scope for them. They ultimately did get funding, but it was not for arts programming. Instead, the foundation identified an opportunity to fund the archival preservation of the journal’s papers. The experience revealed to this leader that sometimes foundations have infrastructure established that does not account for the most urgent organizational needs. As they put it, “The foundation world has to decide if it wants to give away money to help people do things or be an industry with a lot of reports and paperwork, to make people sing for their supper. For example, people like MacKenzie Scott have disrupted philanthropy in a way that other foundations have not.” From her point of view, foundations should create infrastructure to make small grants that support operating costs for organizations or help to build endowments that can lead to multi-generational financial security. Ironically, this, too, is a form of preservation.

People

Resource allocation directly affects who is involved in running the organization’s operations and what role they play. Survey results revealed that many of the organizations rely on volunteers. One director shared that: “We have writers who volunteer as panel hosts and panel participants. We have volunteers who help with our fundraising efforts by spreading the word during fundraising campaigns and leading online fundraising efforts. We have volunteers who help during events by serving as set-up and breakdown crew, volunteering as ushers, etc.” Another director shared the following:

Currently, volunteer labor sustains us and contributions of in-kind labor outweigh direct and indirect costs. Our organization is traditionally underfunded, relying on volunteer labor because our organization is conceptualized as a service opportunity for editors and creatives, and it is difficult to shift to a more sustainable business model; generally organizations and community members mutually benefit from support by volunteers and community engagement.

Synthesizing evidence from the survey and interviews, it appears that while there may be a benefit to maintaining a group of volunteers for certain types of activities, organizations would benefit from funding to support staffing operations that are core to the organization and should be treated as traditional labor. In such cases, ideally, volunteers would be coordinated such that their experience grows their understanding of the field and gives them enriching exposure to the literary arts. An overreliance on volunteers can distract from an organizational goal to develop departments and professionalize roles, inhibiting sustainable growth, as one director explained:

Our organization ran largely on volunteers for many years. We are here today because of unpaid labor. I personally, especially in a Black organization or in a Black endeavor, do not believe that labor should be unpaid. I understand the value of it, but I approach this issue from the perspective of there are dollars out there, there’s plenty of resources out there. They are just not being shared fairly among all who need them. The only reason people really are working for free in these organizations and volunteering is because the resources have not been shared with our organizations to allow us to pay people.

This shift in mentality led this particular director to more frequently make the case to the board and to funders that they need paid staff, who are compensated at market rate, hold professionalized roles with clear job descriptions, and who are accountable. As this director put it, “While there is value certainly in having volunteers, it also is a way of having a lot of unmitigated chaos, because it’s hard for people to be accountable if they are not being paid. I don’t know if it’s entirely sustainable.”

Build a New Shoe

During our interview, Hobson offered a useful framework for thinking about capacity building for small nonprofits: “The nonprofit system is broken right now.” As she explains, nonprofit organizations—particularly many culturally-specific and avant-garde spaces which emerged during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s–have made an impressive artistic and cultural impact even as they have lacked the resources to develop their operations and infrastructure. “We haven’t built a case for a new framework to address the particular needs of our organizations. It’s like Cinderella, we want the shoe to fit, and we actually need to build a whole new shoe.”

Hobson shared an illustrative anecdote from her mother’s experience as a film programmer running several cultural festivals in Atlanta in the 1980s and 1990s:

The Atlanta Department of Cultural Affairs would give her a modest budget, and she was very resourceful. She knew all the contemporary and important filmmakers from across the world. She would write to foreign consulates to see if somebody had the address of a filmmaker and get the film reels sent to Atlanta. We would pick up the films from the airport on the way to my school, and then bring them to the theater. When the filmmakers were invited to travel to participate, they would stay at our house. Sometimes I manned the desk and ran the microphone for Q&As.

In 1990, one of these festivals was hosting a prominent African American actor to perform a one-man show. As she explained, “He had a manager who helped coordinate everything, and I remember both my mom and I being a little in awe of this Hollywood actor who had his own staff. Recently, my mom and I were reflecting on this experience, and she remembered the manager coming to her and saying, with kindness, ‘You’ve treated us so well. Everything has been so personable and wonderful. But why is your ticket desk a folding table next to the ticket booth?'” The venue they were using had a brick-and-mortar ticket booth, but her mother had set up a table in front of it to sell tickets. “She had never thought about it because she had been operating with a lot of grit and chutzpah and with her eleven-year-old child as an assistant in many improvised and non-traditional venues. She had adapted and made do. It had never occurred to her that she could put her volunteer in the ticket booth with the cash drawer, rather than set her up on a folding table as she had always done.”

In Hobson’s consulting, she often finds that this story has current relevance when helping to structure an organization’s vision for the future:

Many organizations I work with came to be because an artist or cultural worker recognized the artistic excellence of communities or artistic modes which haven’t always been recognized—and so the mandate was to figure out a way to connect these artists to their audiences. They came about to do amazing work and did so in adaptive reuse spaces, with volunteer labor. Fast forward, many of these organizations are now established and celebrated institutions in their own right, with an unquestionable artistic legacy, but may still be operating with the infrastructure and mentality of a young organization, not having been supported to transition from emerging to established.

Hobson’s reflections point to a revenue bind that faces many of her clients. Even as they mature programmatically, lack of resources prevents the necessary growth in operations that would help them more fully realize the demand for their programs. If an organization is able to identify the tools and staff it needs, it can speak more effectively to funders about supporting a phase of capacity building. When asked about staffing priorities, leaders revealed that development staff are essential to build relationships with funders and expand the organization’s capacity for grant writing. Sustainable growth is enabled through strategic planning, ideally creating a positive feedback loop, such that each additional staff member enables further growth in one operational aspect or another.

Field Need – Funding operations and assets

The needs of the sector require deeper investments. Funding an organization’s operations with small grants that have a low administrative burden would meet some of the most urgent needs of the field, which could help the organizations to build up the capacity required to be self-sustained. In certain cases, supporting strategic efforts that can help organizations procure an office and programming space would put them on a similar footing with peer organizations in dance, theater, and the visual arts.

Recommendation – Sharing infrastructure

Evidence from our interviews suggests that it would be useful for the Collective to form a committee to investigate the benefits of developing shared infrastructure with the possible goal of shared resources. With buy-in from the Collective, there could be an opportunity for a foundation to support such an initiative that would provide essential resources for operations across the Collective. One possibility for collaborative infrastructure would be to seek funds to contract with an arts administration organization that can support financial processes and workforce administration.

Conclusion

In the course of conducting this research project, a somewhat contradictory set of findings have emerged. Within those contradictions lies a productive friction, which can yield opportunities for the broader cultural sector, as well as the specific organizations in the Collective. That is, these organizations have emerged from adverse social and economic conditions to produce essential spaces for the evolution of Black literature, a field of art whose global value cannot be overstated. At the same time, the evolution of these organizations in such conditions has obscured certain operational and administrative standards that could help them to secure significantly more resources and enable planning processes to create organizational sustainability with an eye towards growth. The formation of this Collective, which has enabled group fundraising efforts and has shaped the scope of this inquiry, lays the foundation for resource and knowledge- sharing within a trusted set of peers.

Opportunities for research and projects building on this report include expanded audience evaluations, consulting on structured planning processes, and convening a group of arts administrators and foundation representatives to begin a dialogue about field needs.[62] Organizations that care about the sustainability of the Black literary arts should understand that there are opportunities to listen and learn from these organizations, a process that can enable meaningful contributions to the field. However, it is essential to approach such conversations with an eye towards administrative flexibility, as leaders in the Collective have repeatedly learned that it is more important to devote their time and resources towards efforts that yield results. It is our hope that this report can shed light on the reality of these culturally significant organizations and serve to narrow the gap in expectations between leaders and funders within the context of the Black literary arts in order to facilitate more equitable resource distribution, such that these important stewards of living culture can be secure in their work.

List of Black Literary Organizing (Past and Present)[63]

We acknowledge that this report only represents a small portion of the Black literary arts community. The Magnitude and Bond research team would like to honor Black literary arts organizations, past and present, by mentioning them below. While this list is not comprehensive, it documents many of the most impactful Black literary arts organizations throughout history.

| 1000BlackGirlBooks | 2015-Present |

| Affrilachian Poets | 1991- Present |

| Africa World Press, Inc. & The Red Sea Press | 1983-Present |

| African American Medical Librarians Alliance (AAMLA) | 1993-Present |

| African Methodist Bethel Society / Bethel A.M.E Inc. | 1815-Present |

| African Poetry Book Fund | 2012-Present |

| African Voices | 1992-Present |

| African-American Film Critics Association | 2003-Present |

| Ahidiana Work Study Center | 1973-1988 |

| All Ways Black | 2021-Present |

| Amsterdam News | 1909-Present |

| Anansi Writers’ Workshop | 1990-Present |

| B.L.A.C.K 2 Life (Bringing Love And Conscious Knowledge 2 Life (B2L)) | 2017-Present |

| Baldwin for the Arts | 2018-Present |

| Banneker Institute of the City of Philadelphia | 1854-1872 |

| Bethel Literary and Historical Society | 1881-1915 |

| Black Americans in Publishing, Inc (formerly known as Black Women in Publishing) | 1979-Present |

| Black Arts Movement | 1965-1975 |

| Black Author’s Association (attached to Literacy Moments Magazine) | 1998-Present |

| Black Caucus American Library Association | 1970-Present |

| Black Classic Press | 1978-Present |

| Black Film Critics Circle | 2010- Present |

| Black Girl Book Collective | 2021-Present |

| Black Girls Stay Lit | 2024-Present |

| Black Lesbian Literary Collective | 2016-2022 |

| Black Literary Theater | |

| Black Men Read | 2016- Present |

| Black Took Collective | 1999-Present |

| Black Women Writers Project | ?-Present |

| Black Writer’s Guild | 1997-Present |

| Black Writers Collective (formally known as The African American Online Writers Guild) | 1998-Present |

| Black Writers Workspace | 2020-Present |

| Black Writers’ Guild of Maryland | 1995-Present |

| BlackWords, Inc or BlackWords Press | 1995-2000 |

| BLF Press | 2014-Present |

| Broadside Lotus Press | 2015-Present |

| Broadside Press | 1965- 2015 |

| Brooklyn Caribbean Literary Festival | 2019-Present |

| Callaloo | 1976-Present |

| Carol’s Books | 1989-2006 |

| Carolina African American Writers’ Collective | 1992/1995-Present |

| Cave Canem Foundation | 1996-Present |

| Center for African American Poetry and Poetics | 2016-Present |

| Center for Black Literature at Medgar Evers College, CUNY –

National Black Writers Conference |

2002-Present |

| City Lit Project, Baltimore | 2004-Present |

| Cleveland African American Library Association (CAALA) | |

| Cleveland Literary Society | 1873-? |

| Cleveland Medical Reading Club | 1925-Present |

| Colored Men’s Union Society | 1839-? |

| Colored Reading Society of Philadelphia | 1828-? |

| Community Book Center | 1983-Present |

| Demosthenian Institute | 1837-? |

| Edgeworth Society | Before 1837-? |

| Eso Won Books | Late 1980s- Present |

| Essence Magazine (originally Sapphire Magazine) | 1968-Present |

| Female Literary Society (New York City) | Before 1831-? |

| Female Literary Society (Philadelphia) | 1831-? |

| Fire & Ink | 2009-Present |

| Fire & Inkwell | 2001-Present |

| Fire!! | 1926-1926 |

| Fiyah: Magazine of Black Speculative Fiction | 2016-Present |

| For Love of Writing (FLOW) | circa 1990s-Present |

| Frederick Douglass Creative Arts Center | 1971-? |

| Furious Flower Poetry Center | 1999-Present |

| George Cleveland Hall Branch Library | 1932-Present |

| Gilbert Lyceum | 1841-? |

| Girl, Have You Read | 2015-Present |

| Great Lakes African American Writers Conference | 2018-Present |

| Gwendolyn Brooks Center for Black Literature and Creative Writing | 1990-Present |

| Gwendolyn Brooks House | Circa 1890-Present |

| Harlem Renaissance | 1920s-1937(circa) |

| Harlem Writers Guild | 1950-Present |

| HBCU Collegiate Literary Societies | |

| Hurston/Wright Foundation | 1990-Present |

| I, Too Arts Collective | 2016-2019 |

| Ideal Literary Society | 1886-1906 |

| Illinois Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) | 1935-1941 |

| Jack Jones Literary Arts | 2015-Present |

| Just Us Books | 1988-Present |

| Kimbilio for Black Fiction | 2013-Present |

| Kitchen Table Literary Arts | 2014-Present |

| Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press | 1980-1992 |

| Kweli Journal | 2009-Present |

| Ladies Literacy and Dorcas Society | 1834-? |

| Ladies Literacy Society | 1834-? |

| Lampblack | 2020-Present |

| Langston Hughes House | 1981-Present |

| Libreri Mapou | 1990-Present |

| Literary and Religious Institution | 1834-? |

| Literary Hall of Fame for Writers of African Descent | 1988-? |

| Literary Society (Poughkeepsie, NY) | Before 1837-? |

| Literary Society of Providence | 1833-? |

| Literary Society, Cincinnati | Before 1843 |

| Literary Society, Columbus | Before 1843 |

| Literary Society, Washington, DC | Before 1837-? |

| Literaryswag Book Club | 2015-Present |

| Lotus Press | 1980-2015 |

| Literary Freedom Project (Publishes Mosaic Lit Mag) | 2005-Present |

| Lyceum at KARAMU (The Playhouse Settlement) | 1915-Present |

| Malik Books | 1990-Present |

| Marcus Books | |

| Margaret Walker Center | 1968-Present |

| Mizna | 1999-Present |

| Mocha Girls Read | 2011-Present |

| Mosaic Literary Magazine | 1998-Present |

| Mt. Zion Congregational Church Lyceum | 1864-Present |

| Nathaniel Gadsden’s Writers Wordshop | 2019- Present |

| National Memorial Bookstore | 1932-1974 |

| New York African Clarkson Society | 1829-? |

| New York Garrison Literary Association | 1834-? |

| NOMMO Literary Society | 1995-2005 |

| Noname Book Club | 2019-Present |

| OBAC | 1967-1992 |

| Obsidian: Literature & Arts in the African Diaspora | 1975-Present |

| Opportunity Magazine | 1923-1949 |

| Other Countries | 1986-2002 |

| Phillis Wheatley Clubs | 1896-Present |

| Phillis Wheatley Society | 1892-? |

| Phoenix Society | 1833-? |

| Phoenix Society, Baltimore | Before 1835-? |

| Power in the Pen Writing Workshop | 2016-Present |

| RAWSISTAZ Reviewers | 2000-2016 |

| Reading Room Society | 1828-? |

| Reading While Black Book Club | 2018-2021 |

| Richard Wright House | 1893-Present |

| Rush Library and Debating Society | 1826-? |

| Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture | 1925-Present |

| Sharp Street Memorial United Methodist Church | 1802-Present |

| Sharp Street United Methodist Church | 1822-Present |

| SistaWRITE | |

| Smart Brown Girl | |

| Society of Young Ladies (Lynn, Massachusetts) | 1827-? |

| Source Booksellers | 1989-Present |

| South Side Writers Group | 1936-? |

| Tawawa Literary Society | 1874-? |

| The African American Literature Book Club (AALBC) | 1997-Present |

| The Bibliophiles | 1987-Present |

| The Brown Bookshelf | 2007-Present |

| The Chicago Black Renaissance Literary Movement | 1930s-1950s |

| The Chicago Defender | 1905-2019 |

| The Clifton House | 2019-Present |

| The Colored Conventions Movement | 1830-1887 |

| The Colored Reading Society for Mental Improvement (The Reading Room Society) | 1828-? |

| The Conscious Kid | 2016-Present |

| The Crisis | 1910-2021 |

| The Dark Room Collective | 1988-1998 |

| The Douglass Institute | 1865-1889 |

| The Free Black Women’s Library | 2015-Present |

| The Messenger | 1917-1928 |

| The Moral Mental Improvement Society | |

| The Paden Retreat for Writers of Color | 1997-? |

| The Paradigm Press | 2020-Present |

| The Philadelphia Library Company of Colored Persons | 1833-1862 |

| The Phillis Wheatley Literary and Social Club | 1916-? |

| The Philomathean Literary Society | 1826-1849 |

| The Reading Room Society for Men of Colour | 1828-? |

| The Symphony Poets | 2011-? |

| The United Black Library | 2016-Present |

| The Watering Hole Org. | 2014-Present |

| The World Stage | 1989-Present |

| Theban Literary Society | 1831-? |

| Third World Press | 1967- Present |

| Thompson Literary and Debating Society | Before 1835 |

| Torch Literary Arts | 2006-Present |

| True Arts Speaks | 2006- Present |

| Tulisoma South Dallas Book Fair | 2003-Present |

| Tyro and Literary Association | 1832-? |

| Umbra Poets Workshop | 1962-1965 |

| US African Poetry Book Fund | 2012-Present |

| Voices of Our Nations Art Foundation | 1999- Present |

| Watts Writers Workshop | 1965-1973 |

| Well-Read Black Girl | 2015-Present |

| Wide Awake and Coral Builders Societies | 1894-? |

| Wintergreen Women Writers Collective | 1987-Present |

| Young Ladies Literary Society | Before 1837-? |

| Young Men’s Literary and Moral Reform Society of Pittsburgh and Vicinity | 1837-Present |

| Young Men’s Literary Society in Boston | Before 1841-? |

| Zora’s Den (Charm City Cultural Cultivation) | 2017-Present |