Reflections on Ethnographic Studies in a Community College Library System

Montgomery College, the community college of Montgomery County, Maryland, has made an enormous contribution to the study of libraries in community colleges with a series of reports about ethnographic studies on all three of its campuses.[1] Tanner Wray, Director of College Libraries and Information Services, led the studies, which gathered information from students and faculty members on how students do their academic work and how library resources, spaces, and services support this work. The Montgomery College project was based on a project conducted previously at the University of Maryland in which Wray played a major role.[2]

The Montgomery College Project: Three Years, Three Campuses, Broad Participation

The Montgomery College project, like the one at the University of Maryland from which it stemmed, comprised studies conducted by librarians and library staff using ethnographic methods and additional ethnographic studies by classes of anthropology students, as well as design work based on study findings by architecture students. Moreover, project leaders recruited stakeholder groups on all three of the college’s campuses to provide guidance to the project and to disseminate findings and bolster outcomes. Stakeholder groups included representatives from major administrative and operational units, as well as librarians and members of the academic staff. Overall, the structure of the program created ties among a multitude of individuals and departments throughout the college while providing innovative teaching and learning opportunities and producing data upon which to base improvements to libraries on all three campuses.

Ethnographic Studies of Community Colleges

While ethnographic studies of four-year colleges and universities abound, they cannot provide the perspectives and the data we need to understand the particular experience of community college students

The Montgomery studies are particularly valuable because they represent the most comprehensive such project yet conducted on community college campuses. While ethnographic studies of four-year colleges and universities abound, they cannot provide the perspectives and the data we need to understand the particular experience of community college students.[3] Ethnographic studies of these students, and of community colleges as institutions, can provide valuable details about the lives and work processes of students and staff and can bring to light the new practices and needs that are emerging under today’s rapidly changing conditions.

An ethnographic literature on community colleges and students is now beginning to emerge, with studies that have looked at leadership,[4] faculty culture,[5] and teaching trends.[6] A set of studies within the Ethnography of the University Initiative at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign looks at student life.[7]

Maura Smale and Mariana Regalado did an important study in two sites within the City University of New York (CUNY) system: City Tech and Brooklyn College. Both institutions grant bachelor’s degrees but City Tech also offers associate degree programs.[8] Regalado and Smale’s subsequent studies have included more community colleges.[9] Rather than take a particular community college library as the unit of analysis, they consider a range of students using libraries on these CUNY campuses, including community college and commuter students, who have much in common. As in the Montgomery College study, Smale and Regalado have found that travel to and from campus affects when and where students do their academic work, noting that some students make use of their time on the bus or the subway to do schoolwork. Students carefully schedule their campus visits so as not to lose more time than necessary to commuting. When they are on campus, students in Smale and Regalado’s studies expressed a need for quiet spaces in which to do their work uninterrupted.[10]

Ithaka S+R is pleased to contribute to the ethnographic literature on community colleges, adding to work that we have published on increasing access to college by low-income and historically underrepresented students.[11] In particular, we have looked at such success factors as strong leadership, cultural change, and the use of data in developing and implementing programs.[12]

Montgomery College

Montgomery College’s mission is to “empower . . . students to change their lives, and . . . enrich the life of our community,” and faculty and staff members share a commitment to student success. Montgomery College provides a variety of general education, continuing education, and workforce training programs to a diverse body of approximately 60,000 students on its three campuses and at other locations across the county. Each campus has a library and the Takoma Park/Silver Spring campus, with a library in the Cafritz Art Center, has two. In addition to classroom buildings and libraries, all campuses provide computer and other labs, cafeterias and student meeting spaces, and event spaces, as well as the full range of student support services. All campuses are commuter campuses and many students arrive for class by car or public transportation. As on other commuter campuses, the length and inconvenience of a student’s commute may affect the frequency of campus visits and the length of time a student remains on campus.

Ethnographic Studies at Montgomery College

The three-year, three-campus ethnographic study at Montgomery College ran from 2013 to 2016. In the first year, the project looked at the use of the library on the Rockville campus. In the second year, it included two libraries on the Takoma Park/Silver Spring campus: the Resource Center and the Cafritz Arts Center Library. In the project’s final year the focus was on the library at the Germantown campus.

In all three years, a project team was recruited and trained to gather feedback using cultural probes (reply cards distributed throughout several areas of the library) and to conduct brief interviews with students intercepted at non-library campus locations. Additionally, at Rockville and Takoma Park/Silver Spring the team conducted design workshops with faculty members, library staff, and students. Across all methods the objective was to understand student work practices and needs in connection with schoolwork done in the library and in other locations. The study also focused on reading and collected data on what students had read most recently, how they learned of the item, how they acquired it, and how and where they read it.

As librarians were conducting these studies, anthropology students were conducting complementary studies. Over three years, several classes of anthropology students conducted observations and interviews to understand current use of the libraries, student and faculty needs and expectations, and whether any changes to library services and facilities could improve concentration, comfort, and outcomes.

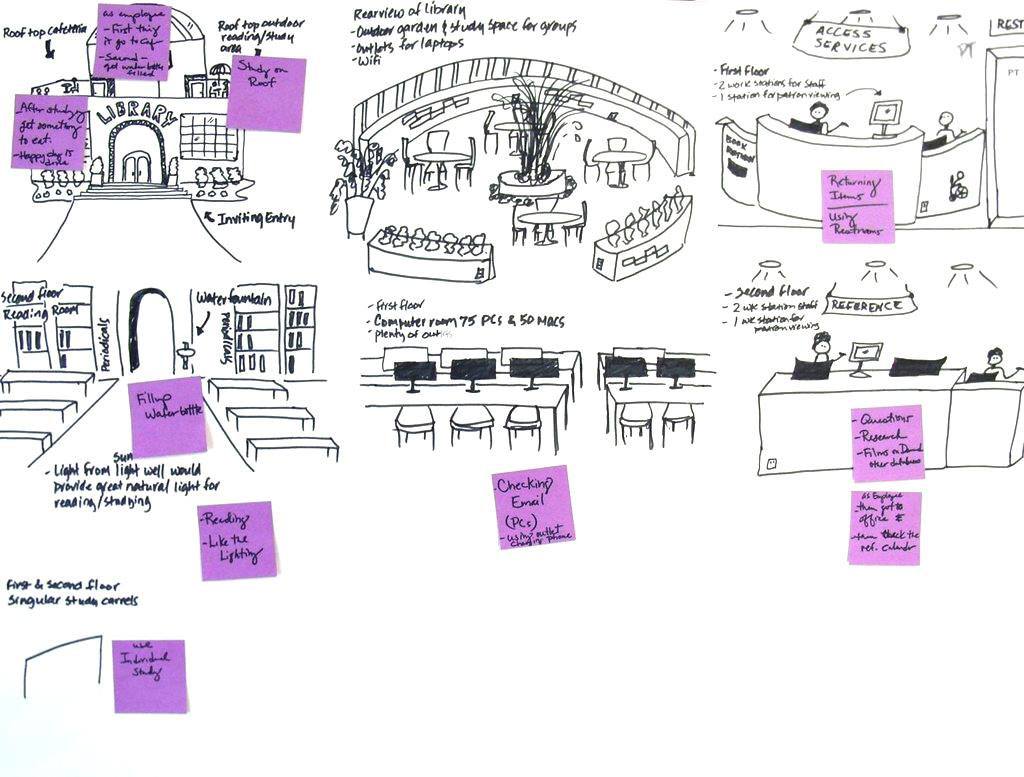

Figure 1. A drawing from a design workshop. Image courtesy Richelle Charles.

Open image in a new window

Honors students participating in the project presented papers at student conferences and, in a further extension of the project, architecture students used the data gathered in the librarians’ and anthropology students’ projects to develop concepts for a re-designed library on the Rockville campus. In the same way the project included faculty members and their students from different programs, it engaged administrators from many departments and all campuses. Representatives of the library and academic and administrative departments attended stakeholder meetings in which they were able to share their perspectives. In this way, the project was a unifying force for the entire college.

Learning from the Studies

Findings

The studies’ many findings are provided in detail in the yearly reports and summarized in the capstone report. Here are some of the insights we gained.

In all three branches of this community college, the library provides a special place for students in which they can give their attention to their studies without distraction. For some students, there are few alternatives. Montgomery College students, like those at other community colleges, tend to be older than students at the four-year colleges that are better documented in the ethnographic literature. Many of them have jobs and family responsibilities that leave little time for studying; they appear to make careful use of their time on campus, grabbing even short stretches of study time when they can.

Students who come to the library are drawn by the things that contribute to an atmosphere of quiet concentration and focus.

Students who come to the library are drawn by the things that contribute to an atmosphere of quiet concentration and focus. This includes everything from suitable furnishings to adequate power and good Wi-Fi as well as noise dampening and soothing décor. Students want to feel welcome and secure. Most reported that they worked alone. Many students reported sitting next to other students although they did not necessarily know these other people. Respondents did not consider commercial establishments, such as coffee shops, to be good alternatives to the library.

Students make extensive use of online information resources but they do not by any means limit their use of these resources to time spent in the library. Reading, in particular, is an activity that most responding students reported doing at home. Furthermore, these students show a marked preference for reading on a screen.

The range of reading materials respondents reported using is quite broad. Not all students at Montgomery College read academic books and articles, and many of the respondents who did so read material recommended by their professors or instructors. Unlike the four-year colleges that are better represented in the literature, all three campuses of this community college offer a wide range of workforce training programs in addition to academic courses. A small but significant number of the students who responded to on-campus interviews had not yet read a book or an article for any class; several had only read from the assigned textbook. Others read charts and other job-related explanatory material or magazine articles and other popular reading material.

Results

Based on the studies done by the library teams and the anthropology students, planning groups on all three campuses have been able to formulate a number of improvements to existing libraries.

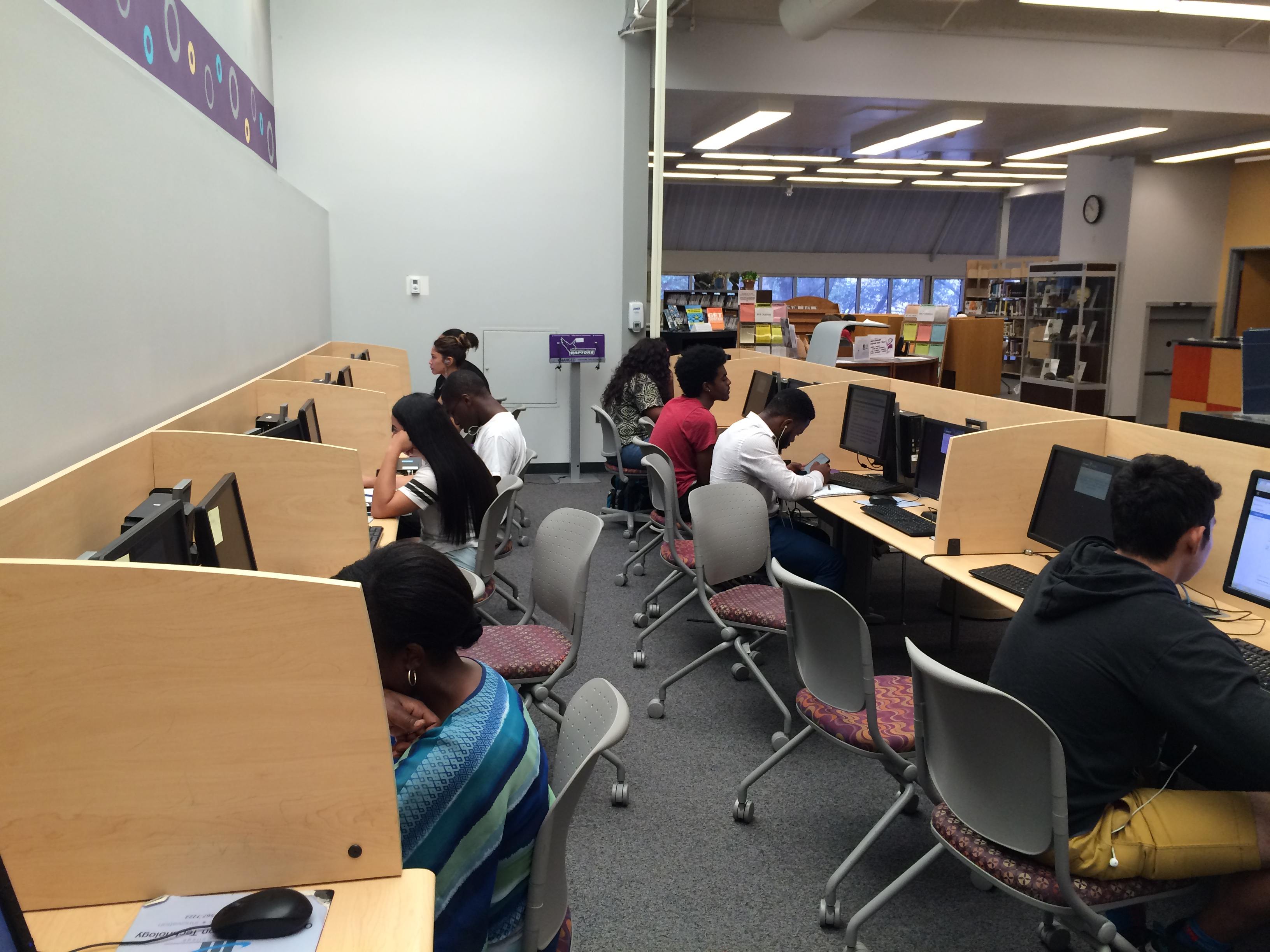

Figure 2. A renovated area in the Resource Center (main library facility) on the Takoma Park/Silver Spring campus with better seating, an expanded work area, and added outlets. Photo by William Curvey.

Changes already implemented across the three campuses include extended hours, upgraded technology (equipment, devices, and power), improved access to electronic resources, more textbooks on reserve, and a better “ambiance” (paint, carpet, furnishings, artwork, and so on). Future changes will focus on more extensive renovation and reconfiguration, more Wi-Fi coverage, and more outreach to library patrons to track and respond to their changing needs.

Other results are more subtle but no less important. The students engaged in gathering data through their Anthropology 201: Introduction to Sociocultural Anthropology class had the opportunity to participate in a “real” and meaningful project through which they learned new skills. Participating library employees also learned new skills and developed better relationships with students and with each other in the process. The college benefited as well, both from the new knowledge developed through the studies and by the emergence of stronger ties across institutional units.

Summing Up

The capstone report reviews the full three-year project, including methods, findings, and implementations, and provides an overview and a guide to the more detailed year-by-year reports.[13] A wide range of project participants wrote the capstone report, providing a view of the project from multiple perspectives: librarian, faculty member, administrator, and student. This is in keeping with the spirit of the project itself, which was based on the belief that community engagement is essential for developing accurate information about student needs and for developing and implementing changes that will help students make the most of their educational opportunities.

Engaging the whole college community around designing the library to help students do their best is an enterprise that works for everyone.

Indeed, one conclusion to be drawn from all three years of the project at Montgomery College is the importance of the library as a space in which students can devote themselves to their own studies away from the demands and distractions of jobs and family. For many community college students, minutes and hours spent in the library are essential to the lives an education will help them forge. Engaging the whole college community around designing the library to help students do their best is an enterprise that works for everyone.

Figure 3. The Gordon and Marilyn Macklin Tower, which houses the library on Montgomery College’s Rockville campus. Photo by Pedro “Pete” Vidal.

To know these students is to understand that their needs may run a very broad gamut and that while their use of scholarly literature may not be as great as at other institutions, their need for the library may be even greater.

Perhaps the most significant lesson to be drawn from these studies is that community college students are exceptionally diverse both in their demographic characteristics and in the pathways they are following through the educational system. Their lives are complicated and they face a wide range of financial, linguistic, and societal obstacles. Some community college students are on a two-year fast track to a four-year college and have the personal and family resources to succeed. But others are in a very different situation, as documented in the Ithaka S+R reports cited above and the ethnographic studies described here. They may be recent immigrants who are still learning English, they may be veterans returned from service overseas, they may be holding down a low-paying job while developing the skills for a better one. Many come from modest backgrounds and are the first in their families to get anything more than a high school education. They may have children of their own, or nieces and nephews, or aging parents or grandparents who need their care, so they squeeze in their classes amid all the other responsibilities. To know these students is to understand that their needs may run a very broad gamut and that while their use of scholarly literature may not be as great as at other institutions, their need for the library may be even greater. To know these students is to want to serve them even more and even better.

Endnotes

- See http://libguides.montgomerycollege.edu/ethnographic?hs=a&gid=3189 to read the reports. ↑

- Patricia A. Steele et al., The Living Library: An Intellectual Ecosystem (Chicago, IL: Association of College & Research Libraries, 2015). ↑

- Constance Iloh and William G. Tierney, “Using Ethnography to Understand Twenty-First Century College Life,” Human Affairs 24 (2014): 20–39, doi: 10.2478/s13374-014-0203-3. ↑

- Diann Milaves Muzkya, “An Ethnography of Community College Presidents from Continuing Education” (Ohio University, 2004), https://etd.ohiolink.edu/rws_etd/document/get/ohiou1108145190/inline. ↑

- Carol Burton, “An Ethnography of Faculty in a Community College and a Public, Regional, Comprehensive University” (Ph.D. Dissertation, North Carolina State University, 2007), http://repository.lib.ncsu.edu/ir/bitstream/1840.16/5669/1/etd.pdf. ↑

- Mary Ellen Dunn, Reclaiming Opportunities for Effective Teaching: An Institutional Ethnographic Study of Community College Course Outlines (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2016). ↑

- “Ethnographies of Parkland Student Life,” n.d., http://spark.parkland.edu/epsl. ↑

- Maura A. Smale and Mariana Regalado, “The Scholarly Habits of Undergraduates at CUNY: Preliminary Results,” January 2011, http://ushep.commons.gc.cuny.edu/files/2011/01/ushep-prelim-report1.pdf. ↑

- Mariana Regalado and Maura A. Smale, “Serving the Commuter College Student in Urban Academic Libraries,” Urban Library Journal, Publications and Research, 21, no. 1 (2015), http://ojs.gc.cuny.edu/index.php/urbanlibrary/article/view/1619/Serving%20the%20Commuter%20College%20Student%20in%20Urban%20Academic%20Libraries. ↑

- Mariana Regalado and Maura A. Smale, “‘I Am More Productive in the Library Because It’s Quiet’: Commuter Students in the College Library,” College & Research Libraries 76, no. 7 (November 2015), http://crl.acrl.org/content/76/7/899.full.pdf. ↑

- Christine Mulhern, Richard Spies, and D. Derek Wu, “The Effects of Rising Student Costs in Higher Education: Evidence from Public Institutions in Virginia” (New York: Ithaka S+R, August 11, 2015), http://dx.doi.org/10.18665/sr.221021. ↑

- Jessie Brown and Martin Kurzweil, “Collaborating for Student Success at Valencia College” (New York: Ithaka S+R, October 29, 2015), http://dx.doi.org/10.18665/sr.274838; Jessie Brown and Martin Kurzweil, “Student Success by Design: CUNY’s Guttman Community College” (New York: Ithaka S+R, February 4, 2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.18665/sr.276682; Jessie Brown and Richard Spies, “Reshaping System Culture at the North Carolina Community College System” (New York: Ithaka S+R, September 10, 2015), http://dx.doi.org/10.18665/sr.273638. ↑

- The capstone report is available at http://libguides.montgomerycollege.edu/ethnographic?hs=a&gid=3189. ↑

Attribution/NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of the license, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.