Serving Library Patrons Behind Bars

Challenges and Collaborations

Introduction

The past several years have seen major shifts in both policy and perception regarding criminal justice in the United States. The distinctly American phenomenon of mass incarceration and its racial and economic underpinnings have made criminal justice reform a major focus of advocacy efforts and a rare example of bipartisan agreement. As a growing quantity of research has begun to illuminate the negative societal impacts of the carceral system, especially on communities of color, focus has slowly shifted to solutions that can provide meaningful opportunities for people impacted by incarceration, improve the conditions of confinement, and break the cycle of recidivism. Perhaps the most salient example of this is the ending of the 1994 ban on eligibility for the federal Pell Grant for people who are incarcerated, which took effect on July 1, 2023. Parallel to this development in education access, and almost along the same timeline, the library community has been working to expand services to support information access in prisons across the country, represented most clearly by the passing of the American Library Association’s (ALA) new Standards for Library Services for the Incarcerated or Detained,[1] which hadn’t been revised since 1992. Despite greater interest throughout the library community in providing services to people who are incarcerated, limited staff capacity, shrinking budgets, and institutional cultures that often conflict with those in departments of corrections have combined to make service provision challenging. Increased collaboration, both between libraries, and between libraries and departments of corrections, has the potential to ease these challenges and facilitate greater access to library and information resources in prisons, but collaboration itself remains a major challenge for the field.

To better elucidate the challenges libraries face in collaborating to provide services to people who are incarcerated, Ithaka S+R, with support from the Institute for Museum and Library Services (IMLS), undertook an exploratory research project to document the different types of libraries involved in providing services (focusing in particular on public, state, academic, law, and prison libraries), the service models and missions those libraries are advancing, the challenges of working both with other libraries, and in collaborating with departments of corrections, as well as opportunities and priorities for providing new, augmented, or wrap-around services. This brief presents our learnings from this work and builds upon our wider expertise and research on higher education in prison programs, which face many similar challenges. Because cross-institutional collaboration is a significant challenge generally, and even more so when the partners are complex and multifaceted institutions like libraries and departments of corrections, it is hoped that this brief will serve as a starting point for further conversations on effective models and productive partnerships.

The State of the Field

Library services to people in prisons and jails, as well as those impacted by the carceral system more broadly, have historically not been a topic of central focus in the broader library community. The past several years have, however, seen a notable shift in focus and visibility. The annual meeting of the American Library Association has been devoting numerous sessions to justice initiatives. Published literature on the topic has also begun to gain traction in the field, most notably Jeanie Austin’s Library Services and Incarceration: Recognizing Barriers, Strengthening Access, which concludes with a chapter on building support and developing services.[2] Several major grant-funded initiatives have likewise brought greater visibility to the topic. The New York Public Library received funding from the Mellon Foundation to seed reference by mail programs at other library systems across the country, while the San Francisco Public Library, through its Jail and Reentry Services Department, has undertaken a major initiative to map library services to people in prison across the country as well as provide training on service provision through a partnership with ALA.[3] These initiatives have proceeded alongside the growth of various library professional communities dedicated to the topic, including the ALA interest group, Library Services to the Justice Involved, and the Abolitionist Librarians Association.

While these national efforts may reflect a surge of interest among librarians at the local level to increase services to people held in prisons and jails, different libraries, or more specifically, different types of libraries, engage differently depending on their mission, resources, capacities, and location. In this project, we focused on the following types of libraries:

- Public Libraries: Serve their surrounding communities by providing access to literature, technology, workshops, and meeting spaces.

- State Libraries: Provide research and reading materials to a broad base of individuals and institutions.

- Academic Libraries: Typically associated with higher education in prison programs with a mission to serve the academic needs of individuals enrolled in the program, rather than the general prison population.

- Law Libraries: Serve the legal reference needs of individuals in prisons, either as they work with legal counsel to appeal their case or as pro se litigants. Different jurisdictions have instituted different law library service models to fulfill their obligations under the law.

- Prison Libraries: Serve individuals who are incarcerated within their various facilities.

Each of these types of libraries have distinct, though overlapping, service models and missions. Whether or not the library recognizes people who are incarcerated as members of their patron base, and deserving of equitable access to services, cuts across these distinctions. Indeed, the stigma surrounding incarceration often prompts discussions about what persons who are incarcerated are deserving of, and whether limited resources should be allocated to their benefit. Logistical challenges to providing services further complicate the balance of ethical obligations and financial constraints. Many prisons are located in remote areas, potentially hours away from a public, academic, or law library, while conflicting or overlapping service areas can further complicate the division of responsibility and resources across libraries serving the same patron base.

Providing any kind of service inside of a prison or jail is challenging. The ultimate priority of departments of corrections is security, and it is the security staff that holds the final say over all programming within a facility. This is further complicated by the fact that the policies of every state department of corrections, and of every facility within a state, are different, with different cultures and risk tolerances. Indeed, practitioners in the field often describe a feudal system wherein each facility is run as the individual fiefdom of the warden.[4] The sheer heterogeneity of the landscape is likewise a drain on resources. Best or general practices can be difficult to outline, and individual libraries are often forced to develop bespoke plans for service provision, tailored to the constraints of the facilities in which they work.

Approach

Given these concerns and the importance of the local context in determining “what works,” it can be difficult to identify universally applicable recommendations for effective partnerships that will lead to sustainable services for people who are incarcerated. To document the challenges, strategies, and best practices for building sustainable library services for people who are incarcerated, and more specifically, the role of collaboration, Ithaka S+R undertook a multiphase project centered around capturing the experiences and perspectives of librarians currently providing services, corrections staff, and persons directly impacted by the justice system.

Our initial approach was to convene a series of virtual community calls with different stakeholder groups (public, state, academic, law, and prison librarians, along with departments of corrections staff), alongside two focus groups with system-impacted individuals. The goal of these engagements was to further explore collaboration challenges, determine stakeholder priorities for providing services to system-impacted people, surface the most promising or likely opportunities for implementing services, and identify the respective needs of each partner to ensure success. To encourage candid discussions and information sharing, these engagements were not recorded.

Though the community calls were planned as the centerpiece of the project (and its primary mode of information gathering), we quickly learned that the calls were not ideal for collecting the kind of information we sought. The first community call, focused on academic librarians, included more than 40 participants. This attested to significant interest and enthusiasm in the community to connect on this topic, but it became difficult to focus the conversation on the more meta concern of the project—collaboration—as opposed to the more immediate needs of the participants, namely service models and problem solving. This may also be a reflection of the professional backgrounds and current roles of the librarians who are most likely to engage in a forum on this topic, namely front-line staff, as opposed to library leaders who may be better positioned to comment on the challenges of institutional collaboration.

To collect information more relevant to the study, we shifted away from community calls and focused instead on one-on-one interviews, where the flow and focus of the conversation could be more tightly controlled. We relied on snowball sampling, asking advisors and known contacts to recommend candidates to participate in semi-structured interviews. Interview guides for different librarian types were developed and adjusted as needed after initial interviews were conducted. The interviews were not recorded, and interviewees were granted anonymity to encourage candidness, though detailed notes—which inform this brief—were taken. In total, we conducted eight interviews with librarians from the various communities participating.

Following the interviews, we recruited individuals who were formerly incarcerated to participate in a focus group to understand their experiences with different types of libraries, the services those libraries offered, and where they experienced gaps in service, or saw potential for greater investment. We conducted outreach through a variety of listservs, LinkedIn, and established networks such as the Formerly Incarcerated College Graduates Network. Advisors provided additional contacts. The focus groups were held over Zoom using the engagement platform Mentimeter to collect responses from the group. As with the interviews, we did not record the sessions to encourage frank discussions, though a dedicated notetaker was present to document the conversation. As with the community calls, we discovered several challenges to this approach. To keep the discussion manageable, the groups were capped at no more than seven participants. However, attendance turned out to be much lower, with only two to four participants attending each focus group. Further, participants who did join often did so from a smartphone, making engagement in both the video conference (Zoom) and engagement platform (Mentimeter) more challenging.

Based on this initial experience, we decided to add a third focus group and invited a larger number of participants to join. We decided the benefits of the Mentimeter platform outweighed its drawbacks but included the option for participants to verbally communicate their responses as well, which the moderators could later account for in the outputs from the Mentimeter platform. We also sent more reminder emails prior to the focus group and made it clear that access to a computer, rather than, or in addition to a smartphone would allow for the best engagement, though a computer was not required to participate. Finally, we increased the honorarium for participation from $100 to $200 to encourage attendance (we also retroactively increased the honoraria for the participants in the initial focus group). These measures proved to be moderately effective, and though attendance still remained below the limit of seven participants, the discussions were nonetheless rich and informative.

After the community calls, interviews, and focus groups, we analyzed the detailed notes using a grounded approach to coding. Below, we synthesize our findings and make recommendations for future work.

Findings

Training and Service Development

Providing high-quality library services in carceral facilities is challenging and the context is markedly different from other library environments. It is notable, therefore, that none of the interviewees had received specific training in prison librarianship. Usually considered a “special library” in library and information schools, most of the interviewees noted that there were few opportunities to learn about library services for people who are incarcerated during their academic training. Most of the interviewees began serving patrons who were incarcerated well into their careers, either taking on the responsibility as an additional component of their role or making a career transition to focus on serving people in prison specifically. In both cases, interviewees noted that greater attention to this topic during their academic training, as well as in continuing education resources, and possibly through internship opportunities, would be useful as the field continues to grow.[5]

When developing services for people in prisons and jails, interviewees noted that they typically began by building support in their home institutions. Citing constraints on budgets and staffing, interviewees also remarked that, among various stakeholders, it could sometimes be challenging to justify extending services to people who are incarcerated. While public sentiment towards mass incarceration has shifted significantly over the past couple of years, making these conversations easier, interviewees noted that building support was by no means straightforward: securing buy-in was often an uneven process, with receptivity often varying across library leadership and administration, front-line staff, and community members. In some cases, pointing out the scale and extreme need of incarcerated individuals, and aligning this to the library’s mission to provide service to all individuals in their jurisdiction, was enough to secure sufficient buy-in to pilot a service. Some interviewees noted that showing alignment between the service and larger county- or state-level priorities was an effective strategy, especially if incarcerated and justice impacted individuals had been specifically identified as a priority group, as was the case for one interviewee.[6]

Staffing was a common challenge voiced by the interviewees, especially for librarians providing service inside of facilities. Prisons are frequently located in isolated areas, in some cases several hours from the library (as was the case for one interviewee), thus posing a significant demand on staff capacity and availability. The sometimes onerous requirements departments of corrections place on volunteers (including external librarians), present a further challenge. Staff are frequently required to produce numerous forms of documentation, undergo background checks, and attend orientations; the complexity of these requirements not only places significant burdens on dedicated staff, but constrains service flexibility by effectively limiting on-call or fill-in work to those who are pre-approved to work in a given facility.

The State of Library Services Within Prisons and Upon Reentry

Libraries can serve a variety of functions within facilities. They tend to vary in size, access, and resources offered. Staffing is also varied, often depending on the budget, and personnel can range from a professional librarian to a correctional officer to individuals who are incarcerated. Some librarians or staff are able to provide reading groups and workshops, limited budgets impact the services others are able to offer. Many prison libraries depend on donations and outside organizations, including public libraries, to supply books and resources. Prison libraries were also found to be impacted the most when budget and staffing cuts were made by the department of corrections. And when the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020, the activities prison libraries provide, as well as other educational opportunities, were significantly curtailed.[7] Through interviews with prison librarians, we also found that during the pandemic a number of prison libraries were closed completely or sectioned off to allow for social distancing and quarantining.

Public and state libraries offer space and services where those who have been incarcerated can access the internet, attend workshops focusing on increasing skills to obtain employment, and even find a safe space to get some rest. A lot of these libraries also offer family-focused services that allow patrons who were incarcerated a space to reconnect with their children. Public libraries also offer library cards and interlibrary loans to patrons inside that allow them access to books and materials outside of the prison walls. Many librarians and their staff are also recognizing the need to provide social workers who are able to direct patrons to more specific community resources, such as housing and transportation vouchers, food assistance, and physical and mental health clinics.[8]

Academic libraries generally provide research opportunities for students on their traditional campus; assistance to individuals who are incarcerated typically comes via higher education in prison programs. While students on the outside have increased access to materials the university libraries can provide, students participating in degree work inside prison are restricted to what their professors are able to bring in. Without access to technology, or to resources necessary to conduct independent research, these students rely on campus librarians and staff to provide the articles and material needed to finish their assignments. Much of this access is facilitated by library interns. Students who are interning for traditional college campus libraries receive requests from students or faculty on the inside for materials on specific subject matter or for specific articles. The student intern will then conduct their own research and print out materials and articles to be sent to the student inside. These resources generally have to be approved by the department of corrections staff before the student is able to receive them. Some libraries located at colleges and universities will also provide books and textbooks for students who are incarcerated.

Law libraries provide resources both inside and outside of facilities. For individuals inside, many facilities have separate law libraries or share spaces with prison libraries. These types of libraries offer varied resources, such as access to LexisNexis and other law document services. Law librarians will also look up case numbers and legal forms requested by patrons who are incarcerated. These forms generally cost between ten to twenty cents per sheet. Our research indicated that cost was a barrier, as many individuals who are incarcerated are not paid or have limited funds available to purchase forms. Law libraries outside of prison facilities are typically found within community courthouses, and their hours of operation are generally the same as the buildings they are housed in. Individuals who are incarcerated have some access to these librarians through the mail, prison librarians, family members, or other community members. Lack of evening and weekend hours also presented a barrier for access to the law and legal documents.

Collaborations

While many libraries both in and out of prison facilities were providing resources to their patrons inside, we found scarce evidence of collaborations between libraries themselves (see Appendix A). Partnerships between libraries can prove to be extremely beneficial, but policies and practices within each system can increase barriers and many times prohibit any involvement from outside organizations or institutions. For prison libraries, an individual state’s department of corrections plays a key role in determining many aspects of facility libraries, including hours, budgets, staffing, and technology available. Staff at these facilities change frequently and are in short supply, often limiting the ability to form outside partnerships. Often operated by staff who are themselves incarcerated, prison libraries are limited in different ways in their ability to connect or partner with outside organizations.

For public and state libraries, other challenges present themselves. An illustrative example, involving The Anne Arundel County Public Library in Maryland and its partnership with a local law library, revolves around programming “ownership.” As described in “Bridging the Gap Between Public Libraries & Law Libraries to Improve Access to Justice,” prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, both public and law libraries collaborated effectively to program and cross-promote in-person events. When events were switched to remote, however, public libraries did not want to include the law library’s events since they weren’t in their locations.[9] This example seemed to highlight the siloing that can occur within organizations, and libraries in particular. When each branch served a different purpose and set of goals, it was difficult for them to be able to work as a collective. According to Valerie Horton, an independent library consultant, libraries can achieve maximum results when they have a clear vision, participation agreements in place, and existing relationships.[10] Communication, the involvement of a broader community, and celebration of early successes were also key to successful collaborations between libraries and their stakeholders.

Some of the other common challenges included a lack of finances, lack of training and a lack of alternative sources of information, changes in scholarly publication methods (open access), and a decline in the importance of the library as a physical entity.[11] How to engage the communities and get them involved was also a challenge in many of the collaborations. Libraries that collaborate with the intention of supporting people who are or were incarcerated face similar challenges of engagement, often exacerbated by the social barriers that exist generally for this community.

While we struggled to find examples of libraries being open to or available for partnerships, we were able to identify frameworks and benefits for these collaborations to occur and be successful. One potential benefit of collaborating is the ability of each individual partner to have access to additional resources and ideas. In “Which Kind of Collaboration is Right For You?,” authors Gary P. Pisano and Roberto Verganti describe four basic modes of collaboration: a closed and hierarchical network (an elite circle), an open and hierarchical network (an innovation mall), an open and flat network (an innovation community), and a closed and flat network (a consortium).”[12] When deciding on an appropriate form of partnership, organizations should decide on open or closed networks and which model would be the most beneficial. Depending on the audience they want to reach and the goals they wish to achieve, any of the four models would prove to be beneficial for library collaborations.

The libraries we looked at lack the staffing and financing to deliver all the services their patrons need. The ability of these institutions to come together would greatly increase the limited resources they do have. In “The Power and Challenges of Collaborations for Academic Libraries,” Jeremy Atkinson notes that library partnerships can provide savings, streamline work processes, and free up staff time for more programming and workshops.[13] For academic libraries in particular, these partnerships can assist in creating a new role on campus and increase services to patrons.

Prison libraries and their patrons would benefit from these collaborations in a multitude of ways. Public libraries, for instance, are better equipped to recognize and provide resources and services for job seekers and on technological and financial literacy. Yet, as Glennor Shirley, a retired Maryland prison library coordinator shares, “Very few public libraries have proactively done outreach or programming in prison. This is a lost opportunity to help inmates to reenter society successfully.”[14]

Collaborating with Corrections

Perhaps one of the most significant challenges in providing library services to people who are incarcerated is the partnership with departments of correction. Similar to colleges seeking to provide higher education opportunities to those inside the prison walls, much of these collaborative challenges are born from very different organizational cultures, imperfectly aligned missions and priorities, and complex, not always legible, organizational bureaucracies. For example, the library’s commitment to the free flow of information is antithetical to the prison’s focus on security and control. The highly idiosyncratic nature of state departments of corrections (and the Federal Bureau of Prisons), and of facilities within the same state system makes it difficult to replicate services or operate in multiple locations. Interviewees also noted the highly relational nature of the work, and that successful collaboration and service provision was often dependent on building trust with key individuals over time. That said, several interviewees also noted that since the COVID-19 pandemic, many departments of correction have experienced staffing shortages and high turnover, changes that have required service providers to rebuild relationships and arrangements from scratch, an exercise that can directly impact service delivery.[15]

Perhaps one of the greatest stumbling blocks, however, comes from the perception that departments of corrections function as a single monolithic entity, which, though a convenient shorthand, obscures the many different roles, units, and philosophies a single department of corrections, or even a single prison, may contain.

Perhaps one of the greatest stumbling blocks, however, comes from the perception that departments of corrections function as a single monolithic entity, which, though a convenient shorthand, obscures the many different roles, units, and philosophies a single department of corrections, or even a single prison, may contain. Interviewees noted that there can be significant differences in attitude and approach between program staff (staff whose main role is to provide programming such as education, substance abuse treatment, or anger management) and security staff (for example, correctional officers whose main role is to enforce order, discipline, and safety in a facility). Despite the reputation for quasi-military uniformity in structure and perspective, significant differences in philosophy, in particular concerning the ultimate purpose of prison, remain between on-the-ground security staff and senior departments of corrections leadership—wardens and commissioners—whose roles often straddle the institutional and public politics of incarceration.

As with successful collaborations between libraries, collaboration with a department of corrections can often be a matter of finding the right ally within the department or specific facility who will champion the library internally. Interviewees noted that their allies were program staff, often those responsible for education, who were more likely to understand the value of access to library services, or in some cases even oversaw the prison library within their own facility. While program staff proved critical allies in numerous cases, interviewees cautioned that because departments of corrections ultimately prioritize security, the security staff have final say on any potential partnership or new service. Thus, while program staff may be supportive, they can be limited in their ability to approve or implement a service themselves. Because of this, understanding the multiple stakeholders and identifying the decision makers within a department of corrections can be critical to a successful collaboration, and mapping this network of power and influence early can be critical to success down the road. Getting to a “yes” is only part of the challenge, however. One interviewee explained that their own project ran into challenges because, while leadership was on board with the project, lower-level staff were not aligned, causing delays later down the road.

Interviewees also described how navigating the limited space and resources available within the prison itself was challenging. As any individual prison is likely to play host to multiple internal and external programs, limited space, time, and staff capacity can drive a sense of competition between programming. When deciding on what programming to support and allow, therefore, departments of corrections leadership may also have to prioritize and make difficult decisions based on the availability of space, time, and staff capacity. The latter consideration is important to note as security staff or other department of corrections staff may be required to be present as a matter of policy whenever a third-party program is operating within the facility. Even an externally funded and staffed program that may seem to be of no or little cost may in fact require the department of corrections to pay for additional staffing or overtime. Having clarity over how a service or program can support and augment existing programming, rather than competing with it, can be a critical component of success.

One interviewee noted that “what is in it for the department of corrections?” and “what are the department of corrections’ priorities?” were the first questions that needed to be answered before going into any partnership. Most departments of corrections’ websites document the mission and values of the department. For example, the New York Department of Corrections and Community Supervision’s mission is,

To improve public safety by providing a continuity of appropriate treatment services in safe and secure facilities where the needs of the incarcerated population are addressed and where individuals under its custody are successfully prepared for release and parolees under community supervision receive supportive services that facilitate the successful completion of their sentence.[16]

More succinctly, Alabama’s department of corrections states that its mission is to, “[provide] public safety through the safe and secure confinement, rehabilitation, and successful reentry of offenders.”[17] It is extremely unfortunate, therefore, that in some cases access to information is viewed as a threat to security and safety, rather than a constructive element of them.[18] The PRISM Project (“Are PRISon libraries Motivators of pro-social behavior and successful re-entry?”), undertaken by the Colorado State Library system provides one example of the efforts to point up and bolster alignment between library and correctional missions. Work being done around higher education in prison programs aspires to drive a similar change in the way access to information is viewed by the correctional community.[19]

As one interviewee pointed out, a potentially less fraught area of alignment may be in supporting reentry success. People who are currently incarcerated have extreme information needs owing to the generally restricted access to information sources prisons allow. When people leave prison, the ability to navigate a world overloaded with information—or information literacy—will be a critical skill. Libraries offer numerous resources that can aid individuals reentering society, such as access to computers and WiFi, resume and employment workshops, legal information for those interested in family reunification and other needs, and more. Defining the unique role and capacity libraries can play in the development and delivery of continuous services (pre and post release), with reentry support as the final component of wrap-around programming, may go a long way toward fostering partnerships that can deliver on the missions of each institution.

Looking Forward: Priorities for Service Development

Library collaboration remains a complex challenge, especially when it involves a non-library partner with very different priorities and cultural norms. However, solving these challenges and building effective and sustainable partnerships is meaningless if the resulting services do not reflect the unique needs and interests of the justice-impacted user base. Here, we synthesize the findings from the focus groups with incarcerated patrons before turning to recommendations for next steps.

“Me Just Killing Time”: Most Used Services During Incarceration

To understand the continuum of services those who are incarcerated might use, and how that might change during different stages of their incarceration, as well as post release, we first asked participants to rank the kinds of library services they used most during their incarceration.

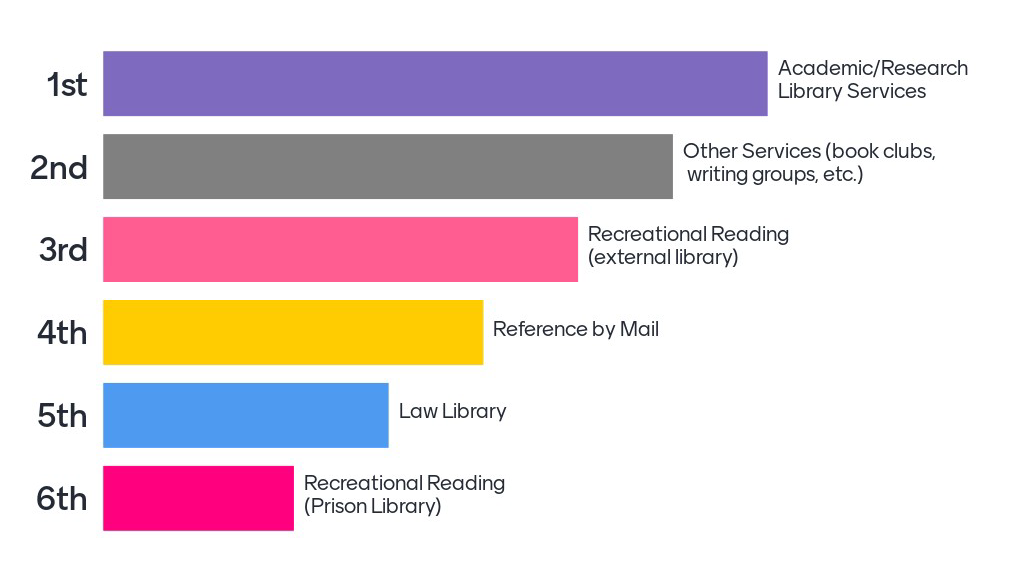

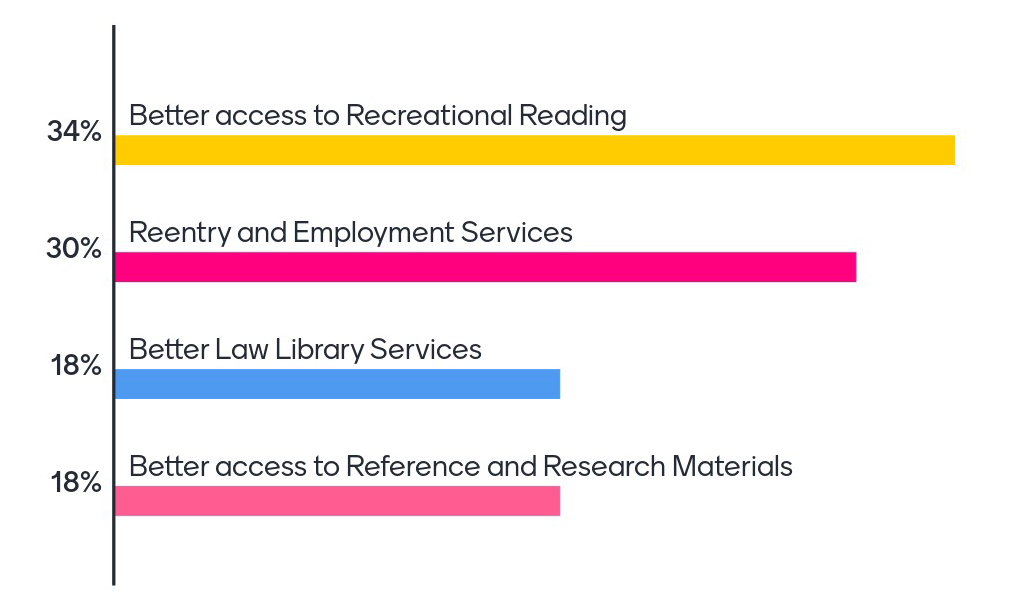

Figure 1: Which library service did you use the most during your incarceration? (Results from Focus Group 1)

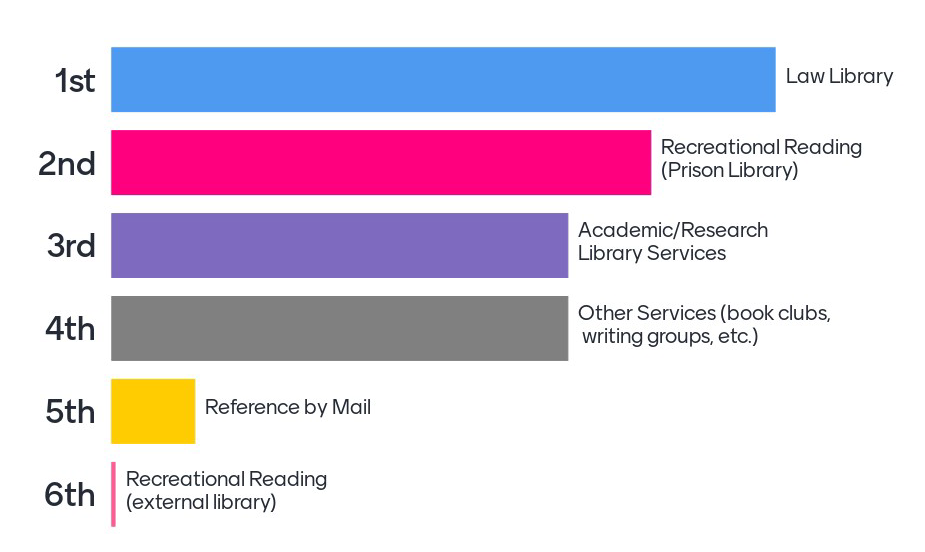

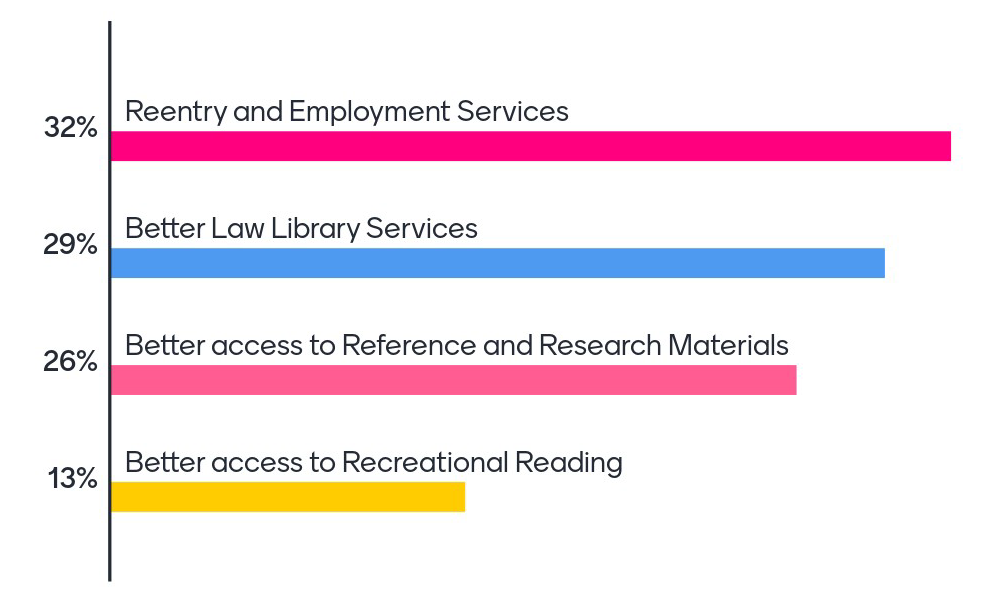

Figure 2: Which library service did you use the most during your incarceration? (Results from Focus Group 2)

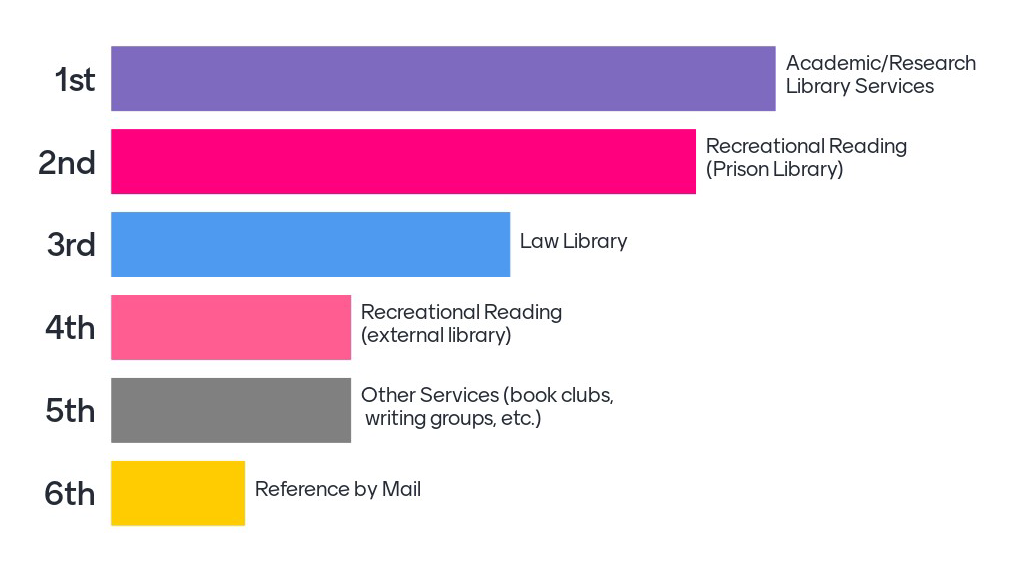

Figure 3: Which library service did you use the most during your incarceration? (Results from Focus Group 3)

Results were noticeably varied between the groups. Further discussion explained some of this variation. Most notably, and perhaps unsurprisingly, the extent to which resources were accessible, and the general quality of the resources, were the largest factor in how frequently participants used them. The significant variability in how prisons across the country staff and resource their libraries should therefore lead us to expect the kind of variation displayed in the groups’ responses. Indeed, these issues can manifest in different ways. Participants in Focus Group 1, for example, rated the law library and the prison library as the resources they most frequently used during their incarceration, but further discussion clarified this use. Some participants noted that the law library was essentially the only library resource in their facility, as the library dedicated to recreational reading was effectively non-existent. Others noted that they typically had superior access to law library resources, as the department of corrections was generally obligated to provide such access. Participants further commented on the logic behind people’s use of certain library resources. For example, one participant noted of the law library that, “a lot of people want to see if they can change things for themselves or others, so a lot of people are looking at laws that might apply to their case or the cases of others. Doing research to change their situation.” The law library, therefore, was one of the few places in the prison where focus group participants said they might feel a sense of agency and control over their circumstances.

Most of the participants across the focus groups had some access to a recreational reading library in the prison, though of widely varying utility. Some noted that while the recreational reading library in their facility was generally well staffed and resourced, the staff member assigned to the library was generally unhelpful and unwelcoming, leading people to rely on other options such as requesting books from family or books to prisons groups. Others noted that in some cases, the “library” was one shelf of books, and any other materials, for example, those sent by family, were heavily censored. As with the law library, participants frequently described the personal value of the prison library, or simply access to books. Leisure was a way of escaping their present circumstances and filling time, as one participant said, “coming to prison young, you’re looking for entertainment, you’re looking for a way to spend your time.” Another noted that he requested many “how-to” books, which was, “me just killing time.”

As the law library and recreational library were often co-located, participants noted that the quality of the access to these spaces was just as important as the quality of the staff and resources. When asked about how much access was granted, one participant simply said, “not enough.” Another provided more detail: the library (containing both law and recreational resources) was open from 7am to 7 pm, which, while sounding like a generous schedule, was never enough. Participants noted they would have to find time between other required programming and work duties, and even when they made it to the library, it only had two computers set up for legal research. Considering that this one space and two computers were shared by 300 people in the unit, and that it was rare to stay in the library for an extended period of time, it was simply impossible for the library to meet the demand. Looming court and filing deadlines made the situation even more precarious, and more desperate for those seeking access to legal information. The security level of the facility or unit, or whether someone was put in solitary confinement, also heavily impacted access to these resources. One participant noted that during a stint in solitary confinement, their mother resorted to printing out short stories and mailing them in as letters, since family correspondence was, per facility policy, the only access they were granted to the external world.

It must be noted that participants also described strategies they employed to work around such obstacles. Many noted the importance of specific prison jobs or programs that afforded additional access to the library, such as serving as a clerk in the library. Others cited timing a visit around count times. As one participant noted, “You have to really know how to move to be able to get time in state prisons…You have to plan knowing your prison ecosystem.”

One participant, for example, described what he called “live Google” wherein questions would be posed to the whole dorm and people who knew the answer (or thought they knew the answer) would respond.

Participants in the focus groups who were enrolled as students in higher education in prison programs during their incarceration noted that access to academic library resources was critical. Focus group participants described challenges that resonate with Ithaka S+R’s previous findings on the provision of resources to support higher education in prions: among the most prominent, little if any access to technologies that would support access to library catalogs and databases, burdensome media review processes, and extensive time lags between requesting resources and receiving them.[20] Of note, however, was the broader importance put on access to these resources by individuals who were not enrolled in higher education in prison programming. Because access to information is so limited in prison, resources that provide it are widely valued. Yet, with technologies forbidden by many prisons, resource provision remains among the most challenging tasks for libraries. As one participant said, “We had no opportunities, no chance, and the library was no help.” In the vacuum of quality information resources, other strategies were frequently adopted. One participant, for example, described what he called “live Google” wherein questions would be posed to the whole dorm and people who knew the answer (or thought they knew the answer) would respond. He would then try to verify the answer the next time he was able to make a phone call. Another participant similarly noted relying on family to research specific topics and mail printouts of articles.

Participants were also frustrated by the lack of coordination between the resources, programming, and collections of libraries and services with other programming inside the prison. Higher education programs may be the most salient example of this, but participants noted other examples. For instance, one facility offered a crocheting program, but the library lacked and was unable to acquire books of patterns. Others noted that substance abuse, anger management, and other treatment programs were common, but the libraries were typically poorly equipped to support individuals who wished to explore these topics more deeply. When the library and programming were aligned it was typically the result of a staff member (not always a librarian) going above and beyond to make it happen.

The Library and Reentry

Reentry is a challenging process, and one that 95 percent of individuals who are incarcerated will undergo. The ability to find and access accurate information is critical during this time, as individuals try to figure out housing, employment, healthcare, family reunification, education, and more. The second half of the focus groups, therefore, focused on the reentry experience in an attempt to identify information-seeking behaviors and where people were likely to go for help and support, as well as to identify potential opportunities for libraries to intervene.

Family and currently or formerly incarcerated peers were the most common sources of support and information for participants across all focus groups. Several participants noted that staff, whether in the department of corrections or through third-party programs could be hard to access. As one noted, “fellow inmates really were the ones who had the experience. Staff who were in positions to help with reentry were very hard to get into contact with.” Others noted that the pre-release programming they received in prison was minimal, with one participant describing it as essentially just three to four hours of programming, which, when weighed against an incarceration of 20 years, is hardly sufficient. Many participants found the lack of accurate information on reentry programs and supports in the community to be frustrating. As one participant explained, “the list that they gave you in [state] was three pages long and two thirds of the organizations and programs didn’t exist anymore.” Another participant recalled that the prison provided an 80-page list of reentry organizations and resources, but that individuals had to pay to have it printed. Given the length of the list and the wages people who are incarcerated are paid, printing the list was simply unaffordable for many.

Most participants noted that upon reentry their information needs shifted dramatically. Whereas recreational, academic, or legal resources were of paramount importance during their incarceration, with reentry, other information needs became priorities. One participant, who was an avid reader and user of the library during his incarceration, explained, “you’re trying to successfully reintegrate into society, which means you have to work, you have family, you don’t have a lot of down time…I haven’t read a single novel since I was released because I haven’t had time.” Figuring out housing, healthcare, and disability benefits were common priorities, and at least one participant noted that everything depended on having an ID or birth certificate, and figuring out how to get these documents was a significant challenge. For participants whose main experience of the library was as a recreational reading resource during their incarceration, it was not immediately clear to them that the library could provide other support upon their release from prison.

Some participants did rely on the library during their reentry. The most commonly-used services included free computer and WiFi access, self-help materials, and resume writing and job application workshops. Participants who did not engage with the library as a part of their reentry expressed that such resources would have been helpful. Help and training with technology was also a common need, as one participant described, “[you’re] entering prison during the era of the Flintstones and coming out to the Jetsons.”

Identifying Priorities

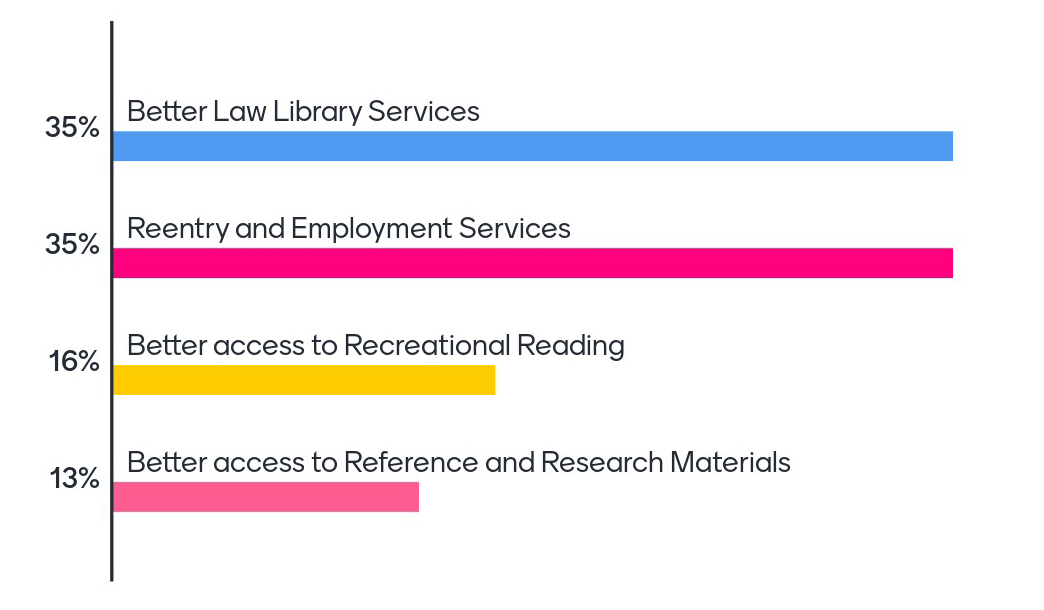

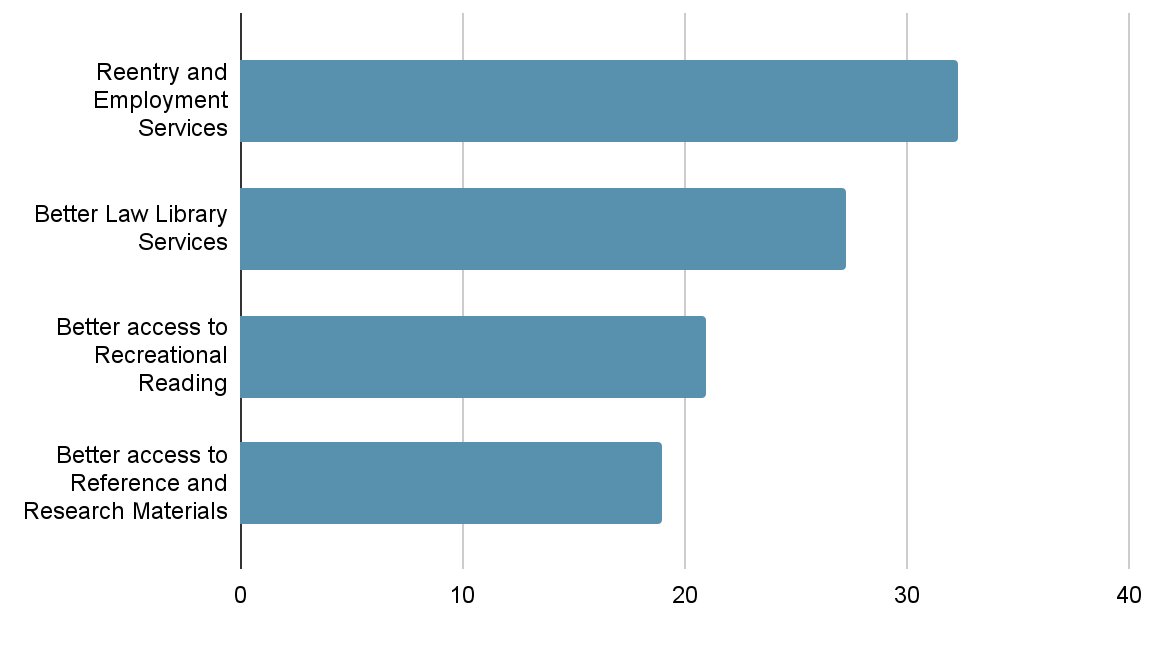

As a final exercise we asked participants to vote on which service areas they would like to see libraries invest in. Participants were given a theoretical 100 dollars which they could divide up as they pleased to invest in different service areas.

Figure 4: If you had 100 dollars, how would you invest it across these services? (Results from Focus Group 1)

Figure 5: If you had 100 dollars, how would you invest it across these services? (Results from Focus Group 2)

Figure 6: If you had 100 dollars, how would you invest it across these services? (Results from Focus Group 3)

Figure 7: Total points scored

Across all three focus groups, participants invested their 100 dollars heavily into reentry and employment services, which gained at least 30 percent of the dollars in each group. This is perhaps unsurprising given that most of the participants had recently navigated or were currently navigating this process, though some acknowledged that such services may be of less use to people with life sentences. Greater investment in law library services was likewise a strong preference among the groups. One participant explained that in the facility in which he was incarcerated, at least three quarters of the population used the law library, and therefore, it should be a focus for greater investment. Others, however, noted that the law library may be of limited utility for those with short sentences, in which case, recreational reading resources and reentry resources may be the most useful. While access to reference and research materials was widely valued, especially for those who had enrolled in educational programming, participants noted that these resources tended to be utilized by a smaller subset of the general population and so, while valuable, were typically a lower priority than other services.

Aligning Library Collaboration and Service Priorities

At the 2023 annual meeting of the American Library Association the new “Standards for Library Services for the Incarcerated or Detained,” which had not been revised since 1992, were officially adopted through a unanimous vote. The impact of this latest revision will hopefully guide libraries toward better service for patrons who are incarcerated, including women, people of color, members of the LGBT community, individuals who are undocumented, youth, and people with disabilities—communities that were not included in the previous revision. The new standards “speak to the potential of libraries to be inclusive spaces of access to information, access to learning, and access to collaboration,” and indeed, collaboration between libraries is held up in multiple places, though occasionally as an “aspirational” goal rather than a best practice per se. Nonetheless, there are various ways that libraries can partner with each other in order to better serve populations who are incarcerated and to assist the formerly incarcerated as they reenter society post release.

Designing Services

- There is an increasing interest in social justice issues among MLIS students. Information schools should develop greater opportunities for their students to explore services to justice impacted patron groups. Continuing education resources should also be a priority.

- When designing wrap-around services during and after incarceration, be attentive to the ways in which people’s needs will change. Consciously shape patrons’ views of what services the library can provide, especially if their main experience of the library is for recreational reading.

- Look for synergies with other programming in the prison. Prisons provide a plethora of programming, looking for opportunities to complement other programming by providing greater depth or expanded opportunities for learning about a subject can meaningfully improve the quality, perception, and utilization of services.

- Map existing infrastructure, physical and technological, and understand where the limitations are and what opportunities might exist to remedy them, for example through departments of corrections’ own contracts.

Building Collaboration

- Consider hours of operation and how services can be co-located to maximize access.

- Conduct a “power mapping” exercise early to identify all stakeholders and identify those with the authority to give approval as well as stakeholders who will be essential to making the project work in practice.

- When looking to collaborate with libraries inside prisons, ask yourself what does the department of corrections have to gain with this partnership or why would they be interested in allowing or participating in this.

Sustainability

- Recognize the expertise of people who are incarcerated and seek their involvement and leadership in service development.

- Explore pathways to librarianship for people who are currently incarcerated. This could take the form of certification or providing an MLIS program inside. This could support sustainability and mitigate the challenge of staff turnover.

Conclusion

When we first began this project, we had little knowledge of how different kinds of libraries were serving patrons who are or have been incarcerated. We were pleasantly surprised by the range and depth of services that we found. Individuals who work at libraries are indeed an innovative, inclusive, and creative community, and the resourcefulness with which they have been able to overcome the barriers to prison service provision is astonishing. Yet librarians need support. We found staff craving community and resources. Our hope with this brief is to have provided useful context on the present state of collaboration to serve patrons behind bars, as well as opportunities for further service development and strategy. The work libraries are doing is essential to the success of individuals who are incarcerated and to the communities they will re-enter upon their return.

Appendix A

This appendix documents previous and ongoing instances of collaboration between, variously, libraries, community-based organizations, departments of correction, prison facilities, and parole boards.

In 2020, Chicago State University (CSU) received an IMLS grant to collaborate with reentry organizations A Way In, and Ex-Cons for Community and Social Change, in an effort to encourage renewal and resilience within the community.[21] CSU also partnered with various community leaders and the Gwendolyn Brooks Library in Chicago. CSU led the Information for Justice Institute (IJI) as they worked to create relationships between various libraries and their staff to better serve patrons experiencing poverty, violence, and incarceration in their neighborhoods.[22] This was initially a one-year project that was extended to two years because of the COVID pandemic. With much of their research being conducted virtually, CSU was able to reach a larger, more diverse pool of participants. A survey sent to librarians, library staff, community leaders, and family members of individuals who are incarcerated focused on their involvement with patrons who are incarcerated, or those who had been released recently. The responses showed that many were not familiar with serving communities impacted by incarceration. The project identified a number of next steps, include bringing librarians and community members together to discuss issues surrounding community needs, and to provide further resources.

The Georgia Public Library Service (GPLS) is collaborating with the Georgia Department of Corrections (GDC) and their prison libraries to increase resources offered to patrons who are incarcerated.[23] In 2017, GPLS began issuing library cards inside prison institutions, giving individuals inside access to more than 11 million items. In addition to increasing access to resources for individuals who are incarcerated, the partnership helped public libraries better understand the needs of their patrons, while introducing prisons to the work of libraries within their communities.

The Colorado PRISM project received their first grant in 2018 from IMLS under what it believed was the auspices of full cooperation with the Colorado Department of Corrections.[24] The lead applicant was the Colorado Library Consortium and the chief collaborators included the Colorado State Library and the Colorado Department of Corrections (CDOC). The information PRISM sought to gather was intended to better assess how and if prison libraries helped in developing and sustaining pro-social behavior, information literacy and learning skills, and preparing people who are incarcerated for successful re-entry into society. In May 2019, a PRISM planning project change request was submitted, stating that “between December 2018 and March 2019, unanticipated changes involving agency leadership resulted in CDOC denying approval of the planning project research request.” The PRISM project lost support from the Office of Planning and Analysis, which they considered to be the “gatekeeper” between CDOC facilities and data and organizations seeking to plan or conduct research. Losing this support meant that researchers were not permitted to survey or interview individuals who were incarcerated or paroled. This also meant that the project no longer had access to existing data on individuals who were currently incarcerated in Colorado. After losing CDOC support, a new partnership was created between the PRISM planning committee and Remerg, a Denver-based non-profit whose mission is “to reduce recidivism by providing current re-entry information to people involved in Colorado’s criminal justice systems.” The project is studying people who are no longer under CDOC supervision, but who have been involved in the criminal justice system and who had access to Colorado prison libraries.

In 2022, the Library Research Service (LRS) received an additional grant to conduct an evaluation of prison libraries studied by the PRISM project. This project seeks to analyze the effectiveness of prison library services related to pro-social behaviors in people who are incarcerated and their successful re-entry into society.[25] LRS is an office in the Colorado State Library and a unit of the Colorado Department of Education. This study differs from a previously proposed project in its focus on persons who are currently incarcerated, along with those who are formerly incarcerated. LRS is partnering with Institutional Library Development (ILD), Remerg, and the CDOC on the study. The Colorado Department of Corrections structures its libraries with a support office, ILD, in the Colorado State Library. The new grant application stated that they will be conducting interviews and focus groups with persons who are currently incarcerated.

The New Jersey State Library partnered with the NJ State Parole Board, NJ Department of Labor and Workforce Development, NJ Public Library, and Free Library of Philadelphia in 2019 to conduct a two-year project for public libraries in New Jersey and Pennsylvania.[26] This project looked at providing services to people returning to their communities after completing their parole time or completing their prison sentences. The group utilized the Fresh Start @ Your Library, a New Jersey State Library program that began in 2009. Fresh Start began by offering group workshops in the Long Branch Free Public Library that taught computer training, job readiness, and tech support for persons who had been incarcerated. Social workers were also in place to assist library staff, allow individuals to feel safe, and to provide necessary resources. Fresh Start expanded to six libraries in New Jersey and to the Free Library of Philadelphia. With the onset of COVID-19, services moved to virtual sessions, and the grant also provided funding for each library to offer GED classes to 50 individuals. The most pressing issues they saw are unemployment, accessible housing, and lack of legal ID.[27] Currently, the program is continuing to offer workshops, technology trainings, and other valuable resources that assist individuals as they reenter society from incarceration.

A collaboration between Princeton University, Columbia University, and the New York Public Library began in 2000 to preserve and make their collections accessible to their members.[28] ReCAP (The Research Collections and Preservation Consortium) is housed on Princeton’s campus and includes over 15 million items. In 2019, Harvard University joined and has since moved over one million books to Princeton. Items are requested through public library catalogs and processed daily, being shipped out to Manhattan and Princeton. Electronic delivery of articles is also available, and materials are sent out to various members of the partner libraries.

Another significant project currently underway features a partnership between the San Francisco Public Library (SFPL) and the American Library Association (ALA). With two million dollars in funding from the Mellon Foundation in 2022, SFPL and ALA began by conducting a survey of existing models of library services to people in jails and prisons, the results of which led in part to a revision of the ALA standards on library services for people who are incarcerated.[29] The survey targeted people who worked with individuals who are currently incarcerated and those who had been released. Survey responses described the need for additional staff training and resources, as well as concerns about censorship by departments of corrections, and the resources that librarians supplied people inside.[30] Virtual training sessions have been developed and implemented for staff and are currently available on SFPL’s website.[31] A mapping service that allows users to locate reentry services available throughout the United States is also available on the website. The map is continually updated as new information is located and new partners add their information.

The Los Angeles Law Library has partnered with various community libraries to offer services to their patrons. These services began in 2019, were paused shortly thereafter due to COVID-19, and resumed in September 2023.[32] The services provided are free to the public and the three branches involved have set hours during which research assistants are present to assist patrons. These assistants are not allowed to give legal advice but will teach individuals how to research their legal issues and refer them to various programs and services offered on the LA Law Library website.

In 2016, several libraries in Maryland joined together to create Lawyer in the Library, a service that is provided to individual public libraries. The Thurgood Marshall State Law Library, the Mayland Access to Justice Commission, and the Conference of Maryland Court Law Library Directors created a curriculum that is offered to public libraries throughout Maryland to support library staff as they provide legal reference services and referrals. Workshops offer clinics that include topics such as housing and landlord/tenant issues, employment wage claims, family law, and information on social security and disability.[33]

Endnotes

- Claire Woodcock, “ALA Council Updates Standards for Library Services for the Incarcerated or Detained,” Library Journal, 30 June 2023, https://www.libraryjournal.com/story/ala-council-updates-standards-for-library-services-for-the-incarcerated-or-detained-ala-annual-2023. ↑

- Jeanie Austin, Library Services and Incarceration: Recognizing Barriers, Strengthening Access (ALA Neal-Schuman, 2021). For a thorough overview of the literature see Jeanie Austin, Rachel Kinnon, Bee Okelo, and Nili Ness, “Trends and Concerns in Library Services for Incarcerated People and People in the Process of Reentry: Publication Review (2020-2022),” San Francisco Public Library, accessed 4 January 2024, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1wZ2tvq5LeBZrdjwiKGBm96LKLHSSZEgG/view?usp=sharing). ↑

- For NYPL see: “Correctional Services Reference-by-Mail Program,” Mellon Foundation, 11 June 2021, https://www.mellon.org/grant-details/correctional-services-reference-by-mail-program-20447151; for SFPL see: “Expanding Information Access for Incarcerated People Initiative, San Francisco Public Library,” https://sfpl.org/services/jail-and-reentry-services/expanding-information-access-incarcerated-people-initiative. ↑

- For reference, Ithaka S+R’s “Security and Censorship” report includes a comparative analysis of 51 state department of corrections’ media review policies and highlights the varying levels of security and censorship. See: Ess Pokornowski, Kurtis Tanaka, and Darnell Epps, “Security and Censorship: A Comparative Analysis of State Department of Corrections Media Review Policies,” Ithaka S+R, 20 April 2023, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.318751. ↑

- Note that creating such resources is a component of SFPL’s Mellon Foundation funded project, in partnership with the ALA. These trainings can be found here on the SFPL website at https://sfpl.org/services/jail-and-reentry-services/expanding-information-access-incarcerated-people-initiative. ↑

- In this context, it is worth noting that the federally funded Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program, which provides “$42.45 billion to expand high-speed internet access by funding planning, infrastructure deployment and adoption programs in all 50 states, Washington D.C., Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, American Samoa, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands,” specifically describes incarcerated individuals as a covered population states are obliged to account for. See “Broadband Equity Access and Deployment Program,” Broadband USA, https://broadbandusa.ntia.doc.gov/funding-programs/broadband-equity-access-and-deployment-bead-program. ↑

- Bianca C. Reisdorf, “Locked In and Locked Out: How COVID-19 Is Making the Case for Digital Inclusion of Incarcerated Populations,” The American Behavioral Scientist PMC9974370 (27 February 2023), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9974370/. ↑

- Elizabeth A. Wahler, Mary A. Provence, John Helling, and Michael A. Williams, “The Changing Role of Libraries: How Social Workers Can Help,” Families in Society 101, no.1 (2020): 34-43, https://doi.org/10.1177/1044389419850707. ↑

- Sara V. Pic, “Bridging the Gap Between Public Libraries & Law Libraries to Improve Access to Justice,” WebJunction, 18 May 2021, https://www.webjunction.org/news/webjunction/bridging-the-gap-between-public-libraries-and-law-libraries.html. ↑

- Valerie Horton, “The Necessity of Collaboration,” American Libraries, November 2021, https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2021/11/01/the-necessity-of-collaboration/. ↑

- Jeremy Atkinson, “The Power and the Challenges of Collaboration for Academic Libraries,” Elsevier Connect, May 2018, https://www.elsevier.com/connect/the-power-and-the-challenges-of-collaboration-for-academic-libraries. ↑

- Gary P. Pisano and Roberto Verganti, “Which Kind of Collaboration Is Right for You?” Harvard Business Review, December 2008, https://hbr.org/2008/12/which-kind-of-collaboration-is-right-for-you. ↑

- Jeremy Atkinson, “The Power and the Challenges of Collaboration for Academic Libraries,” Elsevier Connect, May 2018, https://www.elsevier.com/connect/the-power-and-the-challenges-of-collaboration-for-academic-libraries. ↑

- Stephen M. Lilienthal, “Prison and Libraries: Public Service Inside and Out,” Library Journal, February 2013, https://www.libraryjournal.com/story/prison-and-public-libraries. ↑

- See for example the impact staff turnover had on the Colorado State Library’s PRISM Project: James Duncan,“ Memo,” Colorado Library Consortium, 10 May 2019, https://www.cde.state.co.us/cdelib/prism_planningprojectchangerequest. ↑

- See the New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision’s Mission Statement: https://doccs.ny.gov/about-us. ↑

- See the Alabama Department of Corrections’ Mission Statement: https://doc.alabama.gov/Mission. ↑

- For a more comprehensive overview of this issue see: Ess Pokornowski, Kurtis Tanaka, and Darnell Epps, “Security and Censorship: A Comparative Analysis of State Department of Corrections Media Review Policies,” Ithaka S+R, 20 April 2023, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.318751; “Literature Locked Up: How Prison Book Restriction Policies Constitute the Nation’s Largest Book Ban,” PEN America, September 2019, https://pen.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/literature-locked-up-report-9.24.19.pdf; “Reading Between the Bars,” PEN America, October 2023, https://pen.org/report/reading-between-the-bars/. ↑

- See, for example: Michelle Fine et al., “Changing Minds: The Impact of College in a Maximum Security Prisons,” Open Society Institute, September 2001, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/scans/changing_minds.pdf; Amanda Pompoco, et al., “Reducing Inmate Misconduct and Prison Returns with Facility Education Programs,” Criminology & Public Policy 16 (May 2017): 515-547, https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12290. ↑

- Kurtis Tanaka and Danielle M. Cooper, “Advancing Technological Equity for Incarcerated College Students: Examining the Opportunities and Risks,” Ithaka S+R, 7 May 2020, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.313202; Ess Pokornowski, Kurtis Tanaka, and Darnell Epps., “Security and Censorship: A Comparative Analysis of State Department of Corrections Media Review Policies,” Ithaka S+R, 20 April 2023, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.318751. ↑

- See Chicago State University, “IMLS Grant Announcement,” 2020 https://www.imls.gov/grants/awarded/lg-246366-ols-20. ↑

- See Information Justice Institution, “IMLS Grant Proposal,” 2020, https://www.imls.gov/sites/default/files/project-proposals/lg-246366-ols-20-full-proposal.pdf. ↑

- See Georgia Public Library, “Collaboration Announcement,” https://georgialibraries.org/strengthening-bonds-between-public-libraries-and-prison-populations/. ↑

- See Colorado Library Consortium, “IMLS Grant Announcement,” 2018 https://www.imls.gov/grants/awarded/lg-97-18-0127-18. ↑

- See PRISM, “IMLS Grant Announcement,” 2022, https://www.imls.gov/grants/awarded/lg-252330-ols-22. ↑

- See New Jersey Fresh Start, “IMLS Grant Announcement,” 2019, https://www.imls.gov/grants/awarded/lg-17-19-0082-19. ↑

- See Samhsa Gains Center’s announcement, August 2021, https://www.prainc.com/gains-nj-libraries/. ↑

- See Harvard Library’s press release, January 2019, https://library.harvard.edu/about/news/2019-01-24/research-collections-and-preservation-consortium-recap-expands-scope-and. ↑

- See San Francisco Public Library’s press release, January 2022, https://www.ala.org/news/press-releases/2022/01/san-francisco-public-library-awarded-2-million-expand-services-incarcerated. ↑

- Chelsea Jordan-Makely, Jeanie Austin, and Charissa Brammer, “Growing Services: Libraries Creating Access for Incarcerated People,” Library Journal, August 2022, https://www.libraryjournal.com/story/Growing-Services-Libraries-Creating-Access-for-Incarcerated-People. ↑

- See Expanding Information Access for Incarcerated People Initiative, https://sfpl.org/services/jail-and-reentry-services/expanding-information-access-incarcerated-people-initiative. ↑

- See Santa Monica Public Library Partnership with LA Law Library, June 2019, https://www.santamonica.gov/press/2019/06/17/santa-monica-public-library-announces-partnership-with-la-law-library. ↑

- See Lawyer in the Library Project Overview, September 2016, https://www.mdlab.org/wp-content/uploads/Lawyer-in-the-Library-Project-Overview_September-2016.pdf. ↑