Reflecting Los Angeles, Decentralized and Global

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art is distinguishable from other US encyclopedic museums in three aspects: it is the largest North American art museum west of the Mississippi; it is the youngest encyclopedic museum in the United States; and it is situated in one of the most ethnically diverse metropolises in the world. These characteristics interact in a number of meaningful ways under the museum’s current leadership, allowing its local and global ambitions to complement one another. LACMA is in a moment of transition, and as it rebuilds itself it embraces this local/global dynamic in its mission to provide a “translation of [our] collections into meaningful educational, aesthetic, intellectual, and cultural experiences for the widest array of audiences.”[1] In studying the museum’s complex history, its current programs and operations, and its plans for the future, a portrait emerges of an institution experimenting with bold methods for both increasing accessibility and actively engaging an underserved public. This report explores LACMA’s efforts to break down barriers between departments, better understand their communities and environment, and develop connections between the museum’s civic responsibilities and pursuits toward reflecting Los Angeles.[2]

Key Findings

Among the three encyclopedic museums included in this study, LACMA is the sole West Coast institution.[3] The four-day site visit included 14 in-person interviews (supplemented with subsequent phone interviews), a tour of the galleries, and attendance of public programs. During the visit the following key findings emerged on issues of inclusion, diversity, and equity as they apply to the museum’s program, audience, staff, and board:

- Establishing a Civic Space: By increasing its profile and reflecting its environment, LACMA has become an integrated cultural space in a city that is both highly diverse and highly segregated. Staff see this as a civic responsibility for a county museum.

- Audience Engagement: LACMA staff think critically about how to be good hosts to the public, and they often use contemporary art as access points for cultural conversations. To this end, education and curatorial departments achieved a high degree of collaboration, founded on mutual respect for one another’s expertise.

- Decentralization: Urban planning and environmental factors create barriers to accessing LACMA for many Los Angeles residents. LACMA is finding spaces outside the walls of the museum for its art, and working with the county of Los Angeles to build satellite locations.

Challenges and Tradeoffs

We also observed challenges to increasing inclusion, diversity, and equity in the museum:

- Budget: Training, mentoring, and building a diverse program and pipeline takes resources, both in terms of labor and capital. LACMA has had to learn when to be flexible and when to be stubborn when funding efforts towards equity, diversity, and inclusion.

- Nonhierarchical Approach: Building consensus among staff through nonhierarchical means is an effective way to align staff, but it takes time and requires patience.

History and Context

Los Angeles County comprises slightly over 4,000 square miles of Southern Californian land, includes 88 cities, and roughly 10 million people. Its GDP, at $664 billion, falls between that of Switzerland and Saudi Arabia.[4] Located on the Pacific coast, proximate to Mexico, the region serves as a point of entry to the United States for many cultures.

Los Angeles is the largest of those 88 cities, and the second-largest city in the United States, with a population of nearly 4 million. For decades, it has been a “majority minority” city, and home to many distinct ethnic communities. The city has one of the most diverse populations in the United States, and indeed in the world: the largest Hispanic population in the US resides in Los Angeles, as does the largest Asian population. Los Angeles played a significant role as a settling point during the Great Migration, gaining a large African American population who fled the Jim Crow South in the twentieth century. The city is home to a variety of ethnic enclaves, with prominent populations of Armenian, Turkish, Iranian, Korean, Thai, Cambodian, Vietnamese, Chinese, Filipino, Indian, and Japanese immigrants, among others.[5]

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s origins and development are closely related to the growth of the city. When its predecessor, the Los Angeles County Museum of History, Science, and Art opened in 1913, Los Angeles was experiencing a rapid expansion. In 1870 its population was less than 6,000 people. Fifty years later it was over half a million.[6] Embedded in that expansion is a history of social unrest. From genocide of Native Americans[7] and lynchings of Chinese immigrants in the nineteenth century,[8] to disenfranchisement of African Americans[9] and Latinx in the twentieth,[10] Los Angeles has been a site for minority communities to organize, fight for equal rights, and represent the distinctive cultures that both compose and challenge notions of American identity.[11] As the county’s museum, LACMA has been uniquely positioned to reflect these expressions.

In some cases, its constituents have protested the museum’s failure to do so. Throughout the 1960s, protestors attempted to address the museum’s homogenous representations of culture, both in terms of race and ethnicity, as well as gender. In one instance, a group of roughly 150 demonstrators, many of them artists, marched in protest of a modern art exhibition called Seventeen Artists of the 60s (1981), which featured only white men. Among the ranks of protesters was artist Carol Nieman, who was quoted by the Los Angeles Times: “A person who goes into a public art facility—maybe for the first time in their life—could walk in and by the fact that all the work on the walls in this particular show was done by white males, draw the conclusion that all artists working here in the 60s and 70s were white males. That’s simply not true.”[12] This statement from nearly 40 years ago echoes concerns that are all too familiar as museums still struggle to reflect the diversity of their communities.

Partially as a result of similar protests and grassroots movements within and outside the museum walls, LACMA became a leader in representing African American art in the latter half of the twentieth century, as Kellie Jones explains in South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s.[13] In 1965 Melvin Edwards had his first museum exhibition there as part of Five Younger American Artists. In 1968 the museum held an exhibition titled Sculpture of Black Africa—The Paul Tishman Collection. When attendance from the African American community was low, LACMA staff gathered and appealed to the museum’s security guards, who were mostly black, to develop a strategy to bring the black community to the exhibition. The result was the Black Culture Festival, which drew 4,000 people to LACMA. In 1971 the exhibition Three Graphic Artists included Charles White with emerging artists David Hammons and Timothy Washington. The next year, the exhibition Los Angeles 1972: A Panorama of Black Artists invited 50 black artists to display their work in the museum. And in 1976, aligned with the bicentennial, LACMA held a large historical exhibition, Two Centuries of Black American Art. These exhibitions were helpful in establishing the careers of many black artists, and brought prominence and material security to some of the Los Angeles–based galleries supporting their work, such as Brockman and Heritage. Such institutional support for the visual culture of African Americans was negligible at the time, on a national scale.

But, the museum did not become a presence for many Los Angeles residents until fairly recently. One employee recalled that when she began working at LACMA, most municipal departments weren’t even aware the city had an encyclopedic museum. Museum staff were strikingly consistent in describing LACMA as “sleepy” and “stuffy” until roughly the last decade. Under the leadership of current director Michael Govan, the museum has worked to change this perception. In LACMA, Govan saw an institution ripe for transformation: as the youngest encyclopedic museum in the country, the museum could be redesigned in ways other beaux-arts structures could not; as the largest museum west of the Mississippi, there was potential to become a central hub for Angelinos; and, the location of southern California meant that diversity was a central element of the museum’s goal to reflect its environment.

Diversity at LACMA: Staff and Public

Some may see LACMA as an unsurprising example of a diverse museum—Los Angeles is diverse, and as a county museum LACMA should follow suit. Yet staff who have been at the museum for decades say this wasn’t always the case, asserting that a shift in leadership led to increased diversity. Board member Willow Bay echoed this attitude: “It didn’t happen organically; it happened by leadership. It requires intent. The most important thing is to articulate values and set goals.”

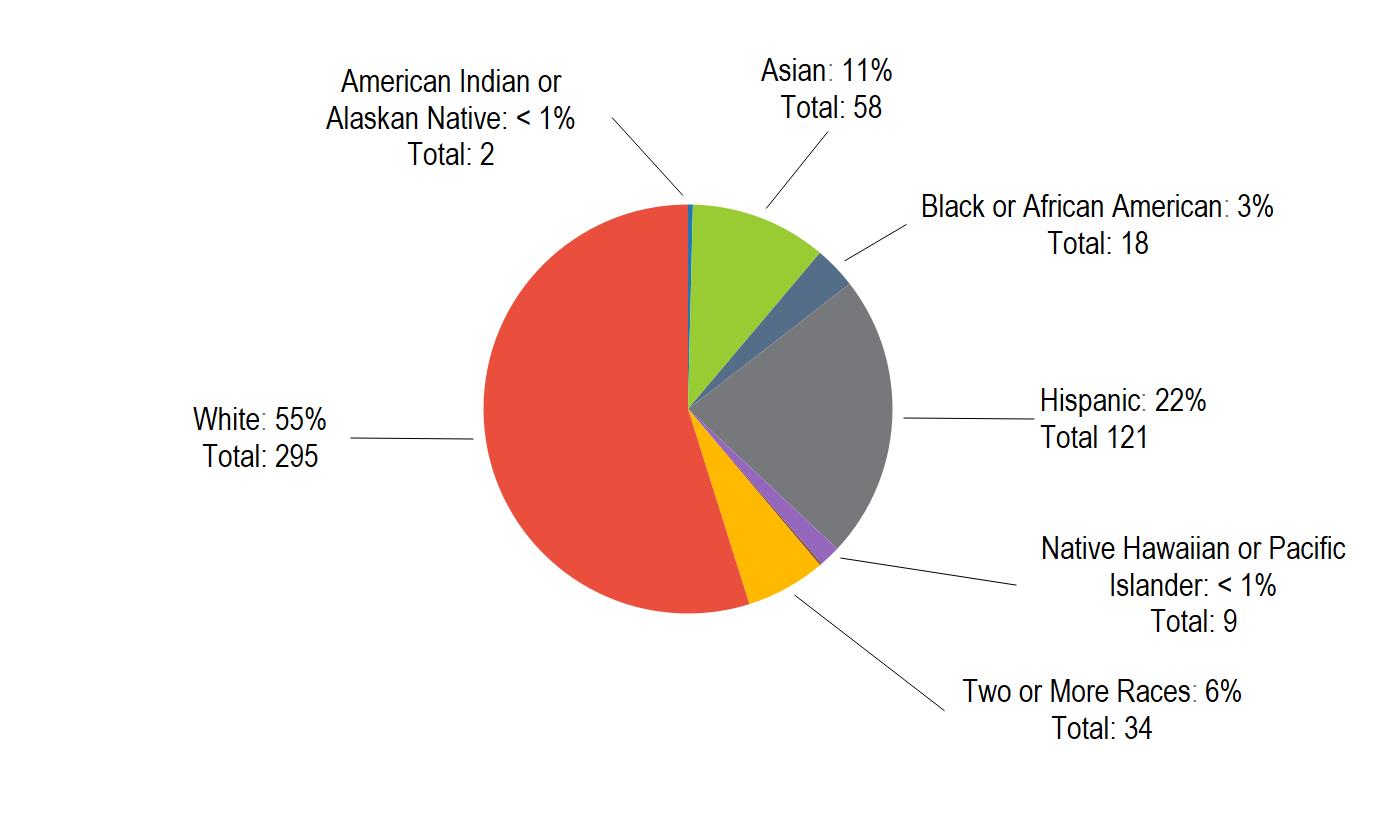

When we surveyed museum staff in 2015, LACMA stood out as one of the few large museums composed of roughly 50 percent employees of color. Figure 1 shows that while the black or African American population is underrepresented, there is a strong representation of Hispanic museum professionals.

Figure 1. LACMA Employee Demographics.

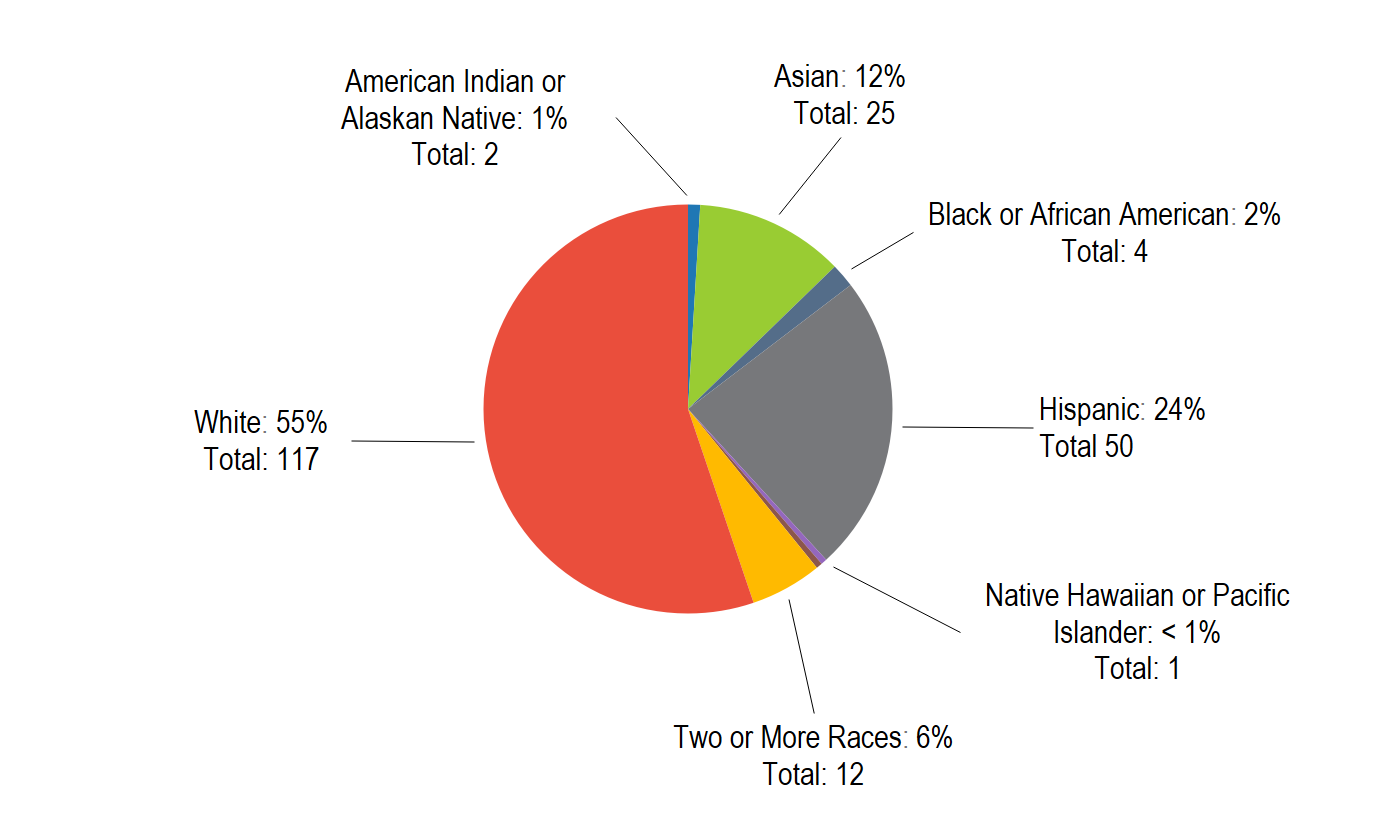

While most museums show a steep decline in the ratio of employees of color in education, curatorial, conservation, and senior administration positions, there was no such drop at LACMA, as can be seen in Figure 2. These data suggest that barriers to “intellectual leadership” may be less present at LACMA than elsewhere.

Figure 2. LACMA Curators, Conservators, Educators and Senior Administrators.

Govan’s focus on civic issues and global art history narratives also brought an awareness of the importance of staff diversity. In part, this emphasis came from consulting with outside experts. One of the museum’s partners, Chon Noriega, director of UCLA’s Chicano Studies Research Center and adjunct curator of LACMA’s Pacific Standard Time: Latin American and Latino Art in LA (PST: LA/LA) exhibition Home, So Different, So Appealing (2017), began to advocate for diversity in the ranks at LACMA. According to Rita Gonzalez, acting head of the contemporary art department, “The argument Chon was making was that diversifying staff needed to be a longer-term initiative, diversifying on higher level. Because if you have a diverse curatorial pool, and an upper-level administration that doesn’t even question it, you curate differently, tell art history differently. That has had a huge impact in the shows that we’ve done, and presentation of the permanent collection, which has diversified. We were the first contemporary art department that was completely curators of color in history.”

If you have a diverse curatorial pool, and an upper-level administration that doesn’t even question it, you curate differently, tell art history differently.

These figures prompted questions of quota-driven diversity efforts. But when asked, we heard from staff and board members that the transformation came from an emphasis on diversity as a core value of the museum. As Bay put it, “I think rigid goals are more confining versus broader thematic goals that allow you to come up with creative solutions. We have goals that align with values, not numbers.” Articulating diversity as a value and developing consensus among staff is a gamble; it is more difficult to measure progress when there isn’t a box to check off. Alternatively, measuring diversity with the familiar representational metrics can lead to reductive thinking, failing to account for a variety of intersecting identities.

Govan emphasizes patience when working to bring about organizational change: “There are two ways to do it. One is to say, ‘I’m going to restructure the administration.’” This approach, from his perspective, can lead to discontent and exodus. “My view is the opposite. You have the long vision and seed with people and then be willing to take time, make sure that every new hire is tested against that model. Then, hopefully, lo and behold you get what you wanted, but without top-down.” Govan has seen that this nonhierarchical approach can be challenging when it comes to persuading certain staff of the values of diversity: “Diversity has been a tough one. A lot of the usual, ‘Well, we can’t think about diversity, we have to think about quality.’ It’s a classic lack of awareness of implicit bias.” But Govan is intent that the museum needs to reflect the people of Los Angeles. In this pursuit, he tries to avoid granting racial diversity primacy over other types of diversity: “I try to make sure it’s not just about skin color, because that is also a problematic in this discussion. Yes, we do need to change the numbers, because we often categorize demographics that way, but economic diversity is just as important.” As staff are invited to own the organizational mission rather than survive a reorganization, a variety of interpretations will naturally emerge as they interact these ideas with their lived and professional experience. Whether these emergent views complement or compete with each other can be difficult to parse, requiring listening, reflection, and guidance from leadership.

County Museum

Los Angeles is one of the most complex urban areas in which a museum could operate. It’s a decentralized city with the heaviest traffic in the United States,[14] and while public transit is currently expanding, the population using transit is declining.[15] The city is very diverse but highly segregated at the neighborhood level.[16] As in much of the country, the ubiquity of car culture can result in a lack of exposure of residents to people outside their own networks. One LACMA employee explained, “In LA, the only time you see people not like you is at the DMV.” It is this homogenized urban experience that LACMA aims to disrupt. As Govan put it, “I try to talk about diversity as non-overlapping networks. I want as many non-overlapping networks here as possible.”

As such, in our interviews staff often articulated that socioeconomic diversity was equal in importance to racial diversity. In several instances museum employees of color and white non-Hispanic employees alike recognized that in Los Angeles, socioeconomic status can be more reflective of opportunities and access to the arts than the binary white non-Hispanic/person of color distinction. Elucidating these observations, one recent UCLA study found that a focus on the intersection of race and wealth yielded a clearer view of disenfranchisement in the city than race alone: “White households in Los Angeles have a median net worth of $355,000. In comparison, Mexicans and U.S. blacks have a median wealth of $3,500 and $4,000, respectively. Among nonwhite groups, Japanese ($592,000), Asian Indian ($460,000), and Chinese ($408,200) households had higher median wealth than whites. All other racial and ethnic groups had much lower median net worth than white households—African blacks ($72,000), other Latinos ($42,500), Koreans ($23,400), Vietnamese ($61,500), and Filipinos ($243,000).”[17] Los Angeles is among the top ten cities in the country in terms of the severity of the wealth gap. However, the study did not show the standard deviation in wealth within these groups, obscuring class disparities within racial/ethnic categories.

While some staff are focused on socioeconomic barriers to access, others emphasize that the museum cannot take for granted a spirit of racial inclusion.

Anecdotally, some LACMA staff shared that the international draw of Southern California and the high degree of wealth in the region mean that racial diversity often is not a proxy for socioeconomic diversity, because there are many wealthy communities of color. But there was not total alignment with this perspective among staff. When asked about access to the museum, one employee of color was critical of the view that the primary barriers to access in the museum were socioeconomic, saying she, “would love for it to be true that access was more about class than race.” From her perspective, more needs to be done to make the museum welcoming to people of color. She has found that certain didactics have included exclusionary language: “Our job was to catch it and make sure we were more welcoming in the way we did our didactics.” While some staff are focused on socioeconomic barriers to access, others emphasize that the museum cannot take for granted a spirit of racial inclusion.

One of the ways LACMA has lowered the financial burden for Angelinos and the broader public is through their youth program, NexGen. The program allows anyone under the age of 17 to gain admission to the museum for free and also grants one free adult admission to the member per visit. There are over 200,000 members of the program. Over 11,000 members come from low-income zip codes, defined as households earning under $32,000 per year.[18]

Within this context, LACMA’s staff are working to make the museum “Los Angeles’s living room.”[19] The increased attendance is indeed staggering. For years museum attendance had plateaued at 600,000 visitors. But in the last decade attendance has risen to 1.4 million and is still on the rise. Govan describes the 600,000 visitors the museum had comfortably drawn for years as the “traditional audience.” To get to 1.4 million, they had to reach out to communities that hadn’t previously felt that the museum was for them.

Public Art

In addition to NexGen, an important aspect of LACMA’s success in increasing attendance and raising the museum’s profile was a strategic investment in public art, accessible outside the museum walls. Diana Vesga, chief operating officer, described the public art on LACMA’s grounds as an essential component of this vision: “The front of the museum is packed at 1am. We’ve had to put guards out in the middle of the night. It’s a young, diverse demographic. Our public sculptures have become a point of engagement for an audience that has been elusive to museum. Eventually they venture into the galleries. We’re the only museum that can say it tripled attendance in such a short time.”[20] When asked about his strategy for raising the museum’s profile, Govan said he “cut the advertising budget,” favoring an investment in several high-profile public installations that would drive the museum’s media presence. With this approach, the museum succeeded in attracting free media coverage through focusing on programming and its collection, rather than paying for advertising. As Govan put it, “What is a museum marketing budget, $2 million? It takes $20 million to market a B movie. There’s not enough resources to do it right, so don’t try.” By bringing works like Levitated Mass and Urban Light to the grounds of LACMA, the museum has become an iconic cultural space on the West Coast, driven in no small part by visitors’ social media engagement.[21] LACMA is now the fourth-most Instagrammed museum in the world. The Louvre, the Met, and MoMA, respectively, occupy the first three positions, each with an audience multiple times that of LACMA’s.[22]

Top: Levitated Mass © Michael Heizer, Photo by Tom Vinetz; Bottom: Urban Light © Chris Burden, Museum Associates/LACMA

Presenting sensational art outside the museum walls is not the only way LACMA has reflected a Los Angeles sensibility for the public.[23] As senior deputy director Nancy Thomas described in her essay, “Collections in the First 50,” “LACMA in the last decade has carved an identity befitting LA: a contemporary and multicultural attitude that acknowledges both the demographic makeup of its community and its geographic position in the world, adjacent to Latin America and facing the Pacific.”[24] The museum boasts some of the largest domestic collections of art of the Pacific Islands, Islam, the Ancient Americas, Korea, Latin America, Southeast Asia, and a growing African art collection. Diversity at LACMA is symptomatic of community engagement, rather than being an end in and of itself. The process begins by making the collection and program reflective of their environment—by becoming a museum of and for Los Angeles.

Creative Budgeting

To finance efforts towards increasing diversity, equity, and inclusion in the workplace, LACMA has had to be both stubborn and flexible. In one instance, Vesga had determined that it was important for all museum staff to undergo diversity training. While some funds were available through a grant to provide training specifically to curators, Vesga felt strongly that the training shouldn’t be focused on a single department. She used her own department’s budget for the training instead. “It has to be a priority, a decision. You need to demonstrate your actions and allocate resources to follow speech,” she said of the decision to draw from her own budget.

In other cases, the museum has to be creative in its allocation of funds. According to Jane Burrell, senior vice president of education and public programs, for the education department the primary barrier to reaching underserved communities is a lack of financial resources. In the 1990s, Burrell says the favorable climate of corporate philanthropy led to large budgets for programming around exhibitions, often over $100,000. Now they are lucky if there is $20,000 in the budget for programs, she says. Since the ‘90s the steep decline in corporate philanthropy and the declining interest in adult education has made it more important for the museum to be creative in its budgeting for public programs.

When the department receives funds, they are often designated for a specific purpose. This is welcome in some cases, such as when the museum received an endowment from the Bing family, which was tied to education activities outside the museum. This restriction is one of the reasons LACMA has a robust presence in Los Angeles schools and communities. “Even if the restriction wasn’t there,” Burrell says, “I definitely would keep that money outside of LACMA. We made a much greater impact in these schools than we ever would here.” While LACMA sees the Bing endowment as a philanthropic success, “the harder part is fending off the crazy ideas”—or preferably, “crafting them into something that makes sense.” As Burrell sees it, “It isn’t easy to come up with funding for your own program, because funders like their own ideas. With funders, you have to take the kernel of interest they have and make it make sense, so they still feel they own it.”

Audience Engagement: Curators and Educators

The shift toward considering the visitor’s experience in a museum can sometimes be framed as an invitation, creating a sense of welcome. Occasionally, though, it is framed differently—as an opportunity for the institution to learn about itself.

José Luis Blondet is the curator for special initiatives at LACMA. He currently works as a curator in the education department, in a role Govan created for him. As a result, he has an unusual perspective when it comes to the dynamics between educators, curators, and audiences.

There are three kinds of archives for a curator to study, as Blondet sees it: collections, documents, and audiences. “We need to treat the history of audience as a living archive,” he explained. Through this framework, Blondet focuses his work on creating access points for audiences to contemporary art, bringing the expertise of both a curator and an educator. “It’s not dumbing down,” Blondet said; “I hate that expression.” Rather, creating access points involves “playing by the rules the artwork has proposed.” In some cases this can leave a work difficult to understand, or even off-putting. Blondet wants to grant the audience permission not to like everything, and to approach contemporary art with their own language, rather than relying on inside-baseball discourses that can feel exclusionary.

In doing so, he has been working closely with the museum’s contemporary art curators, among them Rita Gonzalez, acting head of the contemporary art department. Gonzalez spoke to the connection between departments: “The relationship with education tends to be strong because of the connections between contemporary curators and colleagues in education. For instance, right now Blondet and I are working on an exhibition together. Strong links emerge from that.”

Contemporary Art, a Point of Entry

While it is the central focus of the Broad Contemporary Art Museum (BCAM)—a 2008 addition to the LACMA campus and host this year to multiple PST:LA/LA exhibitions—contemporary art is also integrated into historic collections in several instances, creating access points between the present moment and ancient works.

For instance, the galleries on the fourth floor of the Art of the Americas building progress chronologically, exploring art of Ancient Americas, colonial art of the Americas, and finally contemporary works from Latin American artists, such Roberto Matta’s Burn Baby Burn (1965-66), which represents the Watts riots.

Burn Baby Burn. © ARS, New York / ADAGP, Paris. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Curator and department head of Latin American art, Ilona Katzew, said she included the contemporary gallery at the end of the progression to create a sense of continuity with the present, thereby connecting museum goers’ experience of historical collections with events that have shaped the modern landscape of the city.

In the adjacent building, Linda Komaroff, curator and head of the art of the Middle East department, has made this practice central to her curation of traditional Islamic art. On display amid medieval works are contemporary pieces by Arab artists whose work “builds creative links between the past, present, and future” of Islamic culture.[25] Komaroff described an epiphany she had at an exhibition at the Tate Modern Museum in London several years ago. The installation, which displayed the journals of contemporary Islamic artists, succeeded in engaging the audience in the artists’ lives, a challenge she said she has struggled with in Western settings: “People were looking at the journals and engaging with Islamic art in a way that they hadn’t before.” In observing the audience’s response to the exhibition, Komaroff’s relationship to her own curatorial practice was transformed. In her view, the contemporary works “draw in people who wouldn’t otherwise care,” and she sees it as her job to build empathy by displaying Islamic culture to an American audience. Now she actively pursues contemporary Islamic art and integrates it with older works. She observes that this method works particularly well with youth: “Kids are mesmerized when the images look like them. It’s more interesting! The younger you are the more, well, narcissistic you are. So that’s where you start. Rather than search far and wide, why not change the generation before, change their attitudes to want to pursue this, to feel included and welcome. To feel intrigued. You no longer grab kids based on history, they are more interested in present.” In this sense, Komaroff’s curatorial practice has come to embrace an effort typically associated with the work of education departments.

Collaborations and Mentorships

Both curators and educators at the museum recognize the collaborative spirit that has developed at LACMA as unique. “Educators are often seen as policing curatorial,” Virginia Moon, assistant curator of Korean art, said of the field. “Here at LACMA it’s the complete opposite.” This was a common refrain among the museums profiled in the case studies; when an education and curatorial department achieve a healthy collaboration, staff consider it remarkable.

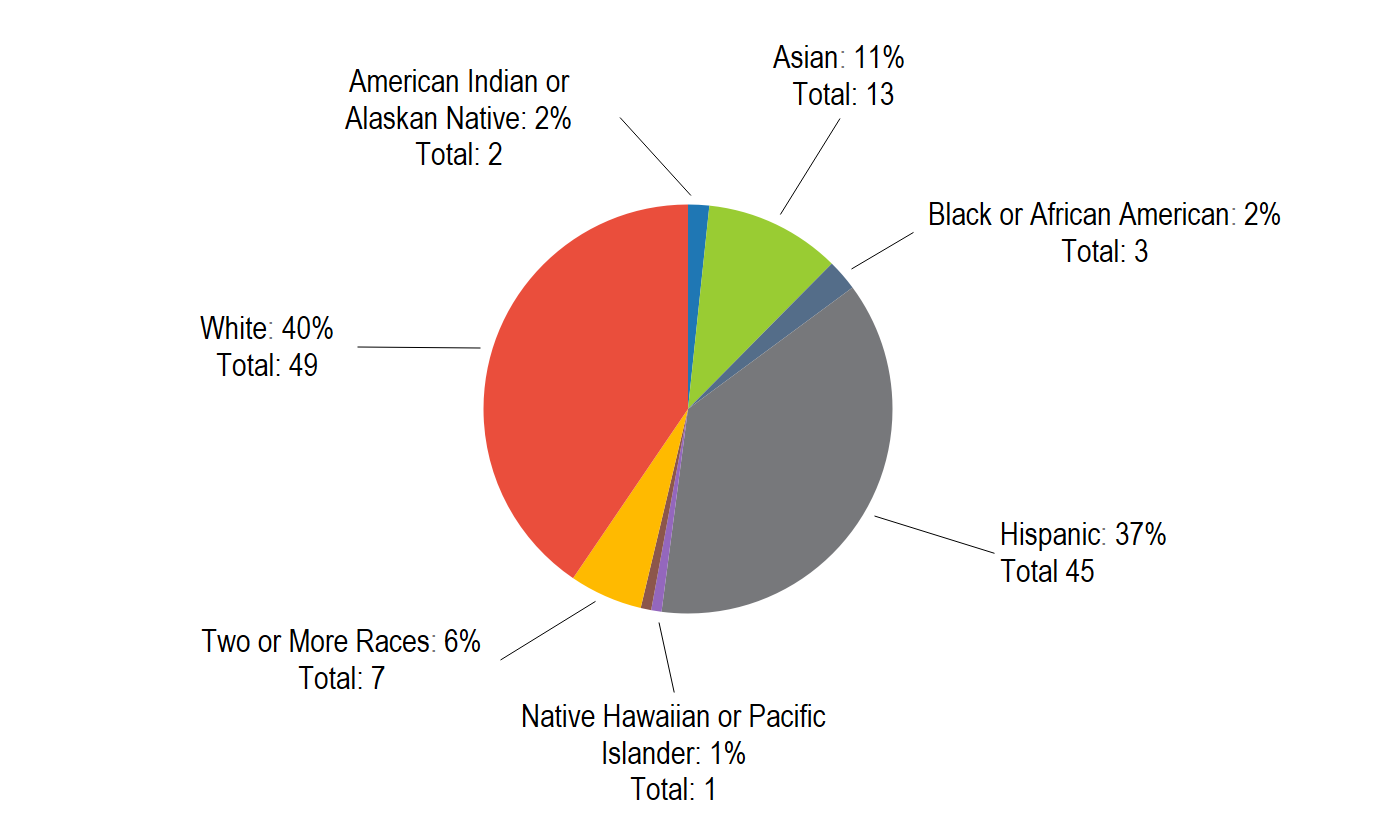

At LACMA, educators are thought of, in some sense, as translators—versed in the language of curation and art history, but also deeply familiar with the communities they serve. Nearly half of the educators are Hispanic, matching the population of the city, which is 47 percent Hispanic, as seen in Figure 3. Staff reported that it was essential for educators to be of the communities they serve, in order to build trust and strengthen connections. Burrell told us, “We want people who are bilingual” in the education department.

Figure 3. LACMA Educators.

In addition to representing a prominent ethnic community, at LACMA many museum educators have expertise in an art history field, whether through an undergraduate or graduate degree in art history, or curatorial experience. LACMA is the rare museum where curators, such as Blondet and Burrell, have transitioned into education departments. This has cultivated a high degree of trust. Educators respect the scholarly approach, and curators also recognize that many LACMA educators bring the perspective of the community they are trying to reach, a valuable asset.

We heard from staff at LACMA and elsewhere that it is uncommon for curators to transition to education departments. In part, compensation is responsible for this. The 2017 AAMD salary survey revealed that the average entry-level salary for education positions is $37,801.[26] That is the second-lowest-paid position featured in the salary survey, after security officer ($33,974). Education coordinator Amber Edwards told us the low pay for educators also acts as a barrier in the field to diversifying the museum, similar to unpaid internships: “If we’re not paying a living wage in big cities, it’s going to be hard to get people to apply if they are not already privileged in some way.”

Edwards told us that the education department is a force for diversifying the museum, in part because they interface with high school students in underserved communities, alerting them to opportunities for internships, fellowships, and hiring. “It’s grassroots,” she said. “We’re able to see potential. Some might not have the written skills to impress on paper, but they have everything else. They have the magic.”

“We’ve hired many of our interns. We’re conscious of shepherding people through the field. We’re especially concerned with mentoring. We want our staff to be a part of the community.”

Nicolas Orozco-Valdivia, a recent graduate of the Mellon Undergraduate Curatorial Fellowship program, was one such individual. His first point of contact with LACMA was through the education department, where he received guidance from Edwards and other colleagues. Edwards explained that his talent was clear to her from an early point, and she made an effort to build a deeper connection between him and the museum. “There’s a little spark, but it’s going to become a fireworks explosion,” she said of the moment. “It goes back to mentoring. We championed him.” Burrell confirmed that these are deliberate efforts in the department: “We’ve hired many of our interns. We’re conscious of shepherding people through the field. We’re especially concerned with mentoring. We want our staff to be a part of the community.”

The Mellon Undergraduate Curatorial Fellowship is thus a strong asset to LACMA’s efforts at outreach and diversification, and provides an example of a formalized mentorship program in practice. In LACMA’s Unframed blog—which Govan established in an effort to make the museum more porous by encouraging staff to write publicly about their work—Orozco-Valdivia writes, “I’ve been given access as a fellow to the specific way in which museums make stories out of this all-messy world, using physical objects as a means of interpreting the past, questioning the present, and envisioning a future.” A few of his experiences with the fellowship included working closely with curators, learning from conservators about handling materials, considering visitor experience with the education department, and visiting the Getty Research Institute to conduct archival research, along with LACMA’s storage facility for large works from their permanent collection. In short, the veneer of the museum has been removed, the operations made apparent. Orozco-Valdivia is one of the few undergraduate curatorial fellows who had the opportunity to compose an exhibition in his time at the museum. Pictured below, Orozco-Valdivia describes his exhibition titled Labor and Photography (2017): “Collectively the photographs offer a rebuke to capitalism’s reductive vision of work as either a daily grind for survival or a money-driven race to the top by encouraging a more nuanced approach to the many ways that concepts of labor and representations of laborers shape our lives.”

Labor and Photography. Photo by LACMA

Orozco-Valdivia is one of a number of students who have engaged in curatorial fellowships intended to diversify the field. Gonzalez told us that these efforts are beginning to yield results: “I’ve seen it in the Getty’s multicultural undergraduate internship program; I’ve seen it at least in effect here at LACMA, seen how that internship program has diversified SoCal landscape. You see people who had their first internship through [the Getty] program. Starting to see it through Mellon fellowship as well.” LACMA recently hired a Mellon undergraduate curatorial fellow from one of its partner museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Gonzalez recognized the value of mentorship in her current position at LACMA, giving credit to Noriega for guiding her curatorial vision. Mentoring is “hugely significant” for diversifying the field, she said.

Access by Design

As LACMA transitions from a seismically vulnerable collection of buildings that have constituted its primary gallery space since moving to Hancock Park in 1965, the museum’s collaborative ethos is being incorporated into the architecture of the space itself.[27] Designed by Peter Zumthor as an expansive, winding structure, which will span both sides of Wilshire Boulevard, LACMA’s new home is projected to open in 2023.[28] Reflecting the composition of Los Angeles, it will have no facade, no grand front entrance—rather, it is flat and sprawling. Its galleries will consist of a single floor, meandering above a public park. The exterior walls of the museum will be glass, with light-friendly art displayed around the perimeter of the building, viewable from the park below.

Projected design of new LACMA building. Photo © NBC Los Angeles[29]

Within this space, Govan envisions a collaborative approach to curation, aiming to draw points of connection between disparate cultures and historical moments. His hope is that by emphasizing these connections, visitors will have more points of entry to multiple cultures, allowing for art historical narratives to be framed in new ways. As Blondet puts it, LACMA’s efforts in thinking critically about visitors’ experience is really just a matter of good manners: “It has to do with hospitality, with being a good host.”

Current projects at LACMA are also a test for a radically different future for the museum as it relates to the city: namely, a decentralized network of museums and partnerships connecting LACMA’s permanent collection to underserved communities.

Prior to assuming directorship of LACMA, Govan tested this model for deepening civic engagement as director at Dia:Beacon, the expansive contemporary art museum 75 miles north of New York City. Govan described a then-prominent view in the field that art museums needed to reinforce commitments to cultivating and researching their collections, and that public engagement was incidental and would result naturally from those efforts. Govan approached this view with skepticism, preferring a multifaceted approach. Indeed, Dia:Beacon not only boasted a world-class collection, but also cultivated relationships with local government with the goal of bringing growth to the area.[30] The experience of connecting an art museum to the public drew him to LACMA. Of LACMA’s present relationship with the city of Los Angeles, he says, “It’s a county museum. The public has a stake in it. You’re dealing with politicians, which is complicated, but it means you have access to other issues. My lunches with supervisors are about homelessness and mental health as much as they are about art.” In observing Govan’s choice to pursue deeper connections between the art museum and county government, something of his approach to leadership can be gleaned: each of his present efforts is, in fact, a test for a future effort that is more ambitious by orders of magnitude. If with Dia:Beacon Govan was testing a model that would be scaled up in LA, current projects at LACMA are also a test for a radically different future for the museum as it relates to the city: namely, a decentralized network of museums and partnerships connecting LACMA’s permanent collection to underserved communities.

The Decentralized Museum

While this process is still in early stages, current strides speak to its potential viability. At “Communicating the Museum,” a conference held in Paris weeks prior to the site visit, Burrell along with colleague Miranda Carroll delivered a presentation focused on making the museum more relevant to the public in the wake of declining attendance across the sector. The presentation explored the ways in which LACMA has engaged historically underserved communities with a strategy of getting outside the walls of the museum. Burrell described a shocked audience. By the end of the presentation, “they were all amazed with how much LACMA does outside the institution,” she said. Indeed, LACMA’s efforts extend well beyond the standard museum commitments to school visits.

For instance, they are making long-term investments in permanent physical spaces, bringing LACMA’s collections into satellite facilities. The first iteration of this was in Charles White Elementary School, five miles east of the museum. Through an initiative called Art Programs Within the Community: LACMA On-Site, LACMA worked with School District 4, identifying an opportunity at Charles White Elementary, a school which was formerly the campus of Otis Art Institute and still includes a dedicated art gallery. LACMA filled the gallery with exhibitions of both commissioned art and pieces from its collection.

This wasn’t a one-off initiative, but a “proof of concept,” Govan says. There are three more off-site locations in the works—one in North Hollywood, another in South Park, and a partnership with Vincent Price Museum in Monterey Park.[31] Govan is looking into a site downtown to act as a node in this network of locations. The intention is to make LACMA like a library system, with branches distributed throughout the city. He describes this as the biggest risk of his career: “Once you start this you can’t go back.”

Govan’s “inherent skepticism” toward hierarchy extends from his management style to his views about the physical spaces that house and display art. “I know architecture and environment is destiny,” he said. “It expresses a worldview, political point of view. So, if there’s a chance to rebuild the image of the museum from a stone block on the top of the stairs, man, this is the place to do it.” By flattening the gallery space and incentivizing collaboration between curatorial departments, Govan hopes to build access into the very structure of LACMA’s central location. [32] By partnering with the city to establish branches throughout Los Angeles, Govan hopes to deepen connections with communities historically excluded from engagement with mainstream art history.

Conclusion

Amalia Mesa-Bains, a Latina artist featured in the PST: LA/LA exhibition Home: So Different, So Appealing (curated in part by Noriega) participated in a panel at last year’s AAMD annual meeting titled “Different Voices: A Social, Cultural, and Historical Framework for Change in the American Art Museum—25 Years Later.” The panel revisited a 1992 conversation about the inclusion of underrepresented voices in the art museum that, at the time, generated a high level of animosity. “This is a déjà vu conversation,” she remarked, though acknowledging that more are willing to listen this time around. After the 1992 incident, which she says “changed my life,” she went home and decided to stop trying to change minds in the field. Instead, she has worked to “build a new generation of leadership within my own community,” having determined that “trying to convert people is not useful.” Reflecting on that historical moment in the field, she added that after the 1993 Whitney biennial the following year, “everything imploded. The door snapped shut.”

But she considers the relevance of an idiom, “You can’t step in the same river twice.” It is clear to Mesa-Bains that some strides have been made. She describes her cohort as a “battering ram”: “This new group is in a much more established place.”

Having engaged in this conversation for decades, Mesa-Bains can reflect on the longevity, or lack thereof, of initiatives that emerge from these conversations. “LACMA is taking an important step,” she remarks, qualifying that “even though I don’t understand why it took so long, I’m happy.”

LACMA’s efforts toward addressing issues of equity, diversity, and inclusion are distinctive in their ambition for permanence. The museum’s leadership works toward building consensus around these values among staff. The investment in public art and free admission with a plus-one for youth has drawn new crowds. The positive relationship between education and curatorial has created a healthy appreciation for both scholarly rigor and accessibility. The decentralizing of the museum will expand access to LACMA’s permanent collection. It is a risk but also a point of pride when Govan says, “Once you start this you can’t go back.”

Appendix

Case Studies in Inclusion, Diversity, and Equity among AAMD Member Art Museums

Three years ago, Ithaka S+R, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD), and the American Alliance of Museums (AAM) set out to quantify with demographic data an issue that has been of increasing concern within and beyond the arts community: the lack of representative diversity in professional museum roles. Our analysis found there were structural barriers to entry in these positions for people of color. After collecting demographic data from 77 percent of AAMD member museums and an additional cohort of AAM art museums that are not members of AAMD, we published a report sharing the aggregate findings with the public. In her foreword to the report, Mariët Westermann, executive vice president for programs and research at the Mellon Foundation, noted, “Non-Hispanic white staff continue to dominate the job categories most closely associated with the intellectual and educational mission of museums, including those of curators, conservators, educators, and leadership.”[33] While museum staff overall were 71 percent white non-Hispanic, we found that many staff of color were employed in security and facilities positions across the sector. In contrast, 84 percent of the intellectual leadership positions were held by white non-Hispanic staff. Westermann observed that “these proportions do not come close to representing the diversity of the American population.”

The survey provided a baseline of data from which change can be measured over time. It has also provoked further investigation into the challenges of demographic representation in this sector. Many institutional leaders are growing increasingly aware of demographic trends showing that in roughly a quarter century, white non-Hispanics will no longer be the majority in the United States, whereas ten years ago the white non-Hispanic population was double that of people of color.[34] This rapid growth indicates that cultural institutions such as museums will need to be intentional and strategic in order to be inclusive and serve the entire American public.

To aid these efforts, AAMD, the Mellon Foundation, and Ithaka S+R partnered again to launch a new effort to understand the following: What practices are effective in making the American art museum more inclusive? By what measures? How have museums been successful in diversifying their professional staff? What do leaders on issues of social justice, equity, and inclusion in the art museum have to share with their peers?

Using the data from the 2015 survey, we identified 20 museums where underrepresented racial/ethnic minorities have a relatively substantial presence in the following positions: educators, curators, conservators, and museum leadership. We then gauged the interest of these 20 museums in participating, also asking a few questions about their history with diversity. In shaping the final list of participants, we also sought to ensure some amount of breadth in terms of location, museum size, and museum type. Our final group includes the following museums:

- The Andy Warhol Museum (Pittsburgh)

- Brooklyn Museum

- Contemporary Arts Museum Houston

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago

- Spelman College Museum (Atlanta)

- Studio Museum in Harlem.[35]

In shaping the final list of museums to profile, we also sought to ensure some amount of breadth in terms of location, size, and type.

We then conducted site visits to the various museums, interviewing between ten and fifteen staff members across departments, including the director. In some cases, we also interviewed board members, artists, and external partners. We observed meetings, attended public events, and conducted outside research.

In the case studies in the series, we have endeavored to maintain an inclusive approach when reporting findings. For this reason, we sought the perspectives of individual employees across various levels of seniority in the museum. When relevant we have addressed issues of geography, history, and architecture to elucidate the museum’s role in its environment. In this way the museum emerges as a collection of people—staff, artists, donors, public. This research framework positions the institution as a series of relationships between these various constituencies.

We hope that by providing insight into the operations, strategies, and climates of these museums, the case studies will help leaders in the field approach inclusion, diversity, and equity issues with a fresh perspective.

Endnotes

- “Overview,” LACMA official website, accessed September 26, 2017, http://www.lacma.org/overview#ms. ↑

- This project benefitted greatly from the contributions of the advisory committee. Our thanks to Johnnetta Betsch Cole, Senior Consulting Fellow at the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; Brian Ferriso, Director of Portland Art Museum; Jeff Fleming, Director of Des Moines Art Center; Lori Fogarty, Director of Oakland Museum of California; Alison Gilchrest, Program Officer, The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; Susan Taylor, Director of New Orleans Museum of Art; and Mariët Westermann, Executive Vice President, The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.We would also like to thank Christine Anagnos, Executive Director AAMD, and Alison Wade, Chief Administrator AAMD, for their organizational support in this project.And we are grateful to Michael Govan, Director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, for his willingness to participate in the study, and Hilary Walter, Coordinator of Curatorial Fellowships, for her many contributions to the project. ↑

- In 2015, Ithaka S+R, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the American Alliance of Museums (AAM), and the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) set out to quantify with demographic data an issue that has been an increasing concern within and beyond the arts community: the lack of representative diversity in professional museum roles. Please see the appendix at the end of this paper for a fuller description of the survey, methodology, and how we selected museums for inclusion in this case study series. ↑

- “Why LA County,” Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation, accessed September 27, 2017, https://laedc.org/wtc/chooselacounty/. ↑

- Mohammad A. Qadeer, Multicultural Cities, (Toronto, New York, and Los Angeles: University of Toronto Press, 2016); Josh Kun and Laura Pulido, Black and Brown in Los Angeles: Beyond Conflict and Coalition, (London: University of California Press, 2013). ↑

- Carolyn Stewart, “Census of Population and Housing,” US Census Bureau, August 19, 2011, accessed September 27, 2017, https://www.census.gov/prod/www/decennial.html. ↑

- Robert F. Heizer and Mary Anne Whipple, The California Indians: A Sourcebook (London: University of California Press, 1971). ↑

- William D. Estrada, The Los Angeles Plaza: Sacred and Contested Space (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2008). ↑

- Robert Bauman, Race and the War on Poverty: From Watts to East L.A. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008). ↑

- Lisa García Bedolla, Fluid Borders: Latino Power, Identity, and Politics in Los Angeles (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007). ↑

- Elizabeth Kai Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016). ↑

- The LA Times also reported that 29 of 713 artists in group exhibitions ten years prior to the article were female, only one of fifty-four single artist shows were female, and over 99 percent of the art displayed in the museum at the time was male. ↑

- Kellie Jones, South of Pico (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017). ↑

- Associated Press, “No surprise here: Los Angeles is the world’s most traffic-clogged city, study finds,” Los Angeles Times, February 20, 2017, http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-traffic-los-angeles-20170220-story.html. ↑

- Laura J. Nelson and Dan Weikel, “Billions spent, but fewer people are using public transportation in Southern California,” Los Angeles Times, January 27, 2016, http://www.latimes.com/local/california/la-me-ridership-slump-20160127-story.html. ↑

- Nate Silver, “The Most Diverse Cities Are Often the Most Segregated,” FiveThirtyEight, May 1, 2015, https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/the-most-diverse-cities-are-often-the-most-segregated/. ↑

- Melany De La Cruz-Viesca, Chen Zhenxiang, Paul M. Ong, Darrick Hamilton, and A. Darity William Jr., “The Color of Wealth in Los Angeles,” Report produced by Duke University, The New School, and University of California, Los Angeles, 2016, http://www.aasc.ucla.edu/besol/color_of_wealth_report.pdf. ↑

- Media Metro, “Los Angeles County Low Income Zip Code List”, accessed 10/23/2017, https://media.metro.net/about_us/pla/images/zipcode_ped_pla_C1120_2017-04.pdf. ↑

- Interview with national fellowship coordinator of Mellon Undergraduate Curatorial Fellowship Hilary Walter. ↑

- Attendance is projected to have tripled from 600,000 by end of year. ↑

- The installation of Michael Heizer’s Levitated Mass incidentally created connections between communities. The 340-ton boulder was brought from Stone Valley Quarry to LACMA in 2012. While the quarry was only 60 miles from the museum, restrictions due to the boulder’s size and weight required a circuitous 106-mile route through the region, at a pace of seven miles per hour. Over the 11-day trip, Angelinos gathered on sidewalks and in crowds to observe the boulder in motion. At its arrival in LACMA, it was greeted by a crowd of over 1,000 people. For more, see Adam Nagourney, “Lights! Cameras! (and Cheers) for a Rock Weighing 340 Tons,” New York Times, March 10, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/11/arts/design/340-ton-artwork-arrives-at-los-angeles-county-museum-of-art.html. ↑

- Ben Davis, “The World’s Most Instagrammed Museums in 2016,” Artnet News, December 02, 2016, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/most-instagrammed-museums-2016-768923. ↑

- Critics cite the architect Renzo Piano’s intention for a minimal landscape for the public. See Victoria Dailey, “Levitated Mass Hysteria: Michael Heizer’s LACMA Installation,” Los Angeles Review of Books, February 2015, https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/levitated-mass-hysteria-michael-heizers-lacma-installation/#! ↑

- Gifts on the occasion of LACMA’s fiftieth anniversary, LACMA, 2015. ↑

- “Islamic Art Now: Contemporary Art of the Middle East,” LACMA official website, accessed September 27, 2017, http://www.lacma.org/art/exhibition/islamic-art-now-contemporary-art-middle-east. ↑

- Association of Art Museum Directors, “2017 Salary Survey”, July 3, 2017, accessed September 28, 2017, https://aamd.org/sites/default/files/document/2017%20AAMD%20Salary%20Survey_0.pdf. ↑

- The new building will replace the Ahmanson Building, the Leo S. Bing Center, the Hammer Building and the Art of the Americas Building. ↑

- Christopher Hawthorne, “Here are the latest designs for LACMA’s $600-million makeover,” Los Angeles Times, April 6, 2017, http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/la-et-cm-lacma-design-20170406-htmlstory.html. ↑

- Alysia Gray Painter, “Building LACMA: New Site Details Future,” NBC Southern California, August 5, 2016, https://www.nbclosangeles.com/news/local/Building-LACMA-New-Site-Details-Future-389339912.html. ↑

- Center for Creative Community Development, “Brief Summary of the Economic Impact ofDia:Beacon in Beacon, New York”, https://web.williams.edu/Economics/ArtsEcon/library/pdfs/DiaBeaconSummary.pdf. ↑

- LACMA’s surrounding area is 63 percent white and 65 percent of residents hold a bachelor’s degree. Compton is about 96 percent black and/or Latino, and fewer than 10 percent of residents hold a bachelor’s degree. Public transit to LACMA from these areas takes over an hour, involving multiple transfers. ↑

- The single floor for galleries is intended to evenly distribute the real estate for various curatorial departments, rather than creating a hierarchy where the first-floor galleries are the most sought after, because they gain the most traffic. For more, see Patrick Lynch, “New Renderings Released of Peter Zumthor’s LACMA Design,” ArchDaily, August 5, 2016, https://www.archdaily.com/792781/new-renderings-released-of-peter-zumthors-lacma-design. ↑

- Roger Schonfeld, Mariët Westermann, and Liam Sweeney, “Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey,” Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, July 29, 2015, https://mellon.org/media/filer_public/ba/99/ba99e53a-48d5-4038-80e1-66f9ba1c020e/awmf_museum_diversity_report_aamd_7-28-15.pdf. ↑

- William H. Frey, “A Pivotal Period for Race in America,” In Diversity Explosion: How New Racial Demographics Are Remaking America (Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2015), 1–20, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7864/j.ctt6wpc40.4. ↑

- We focused on people of color for measuring diversity for two reasons: (1) In the 2015 art museum demographic study, we received substantive data for the race/ethnicity variable, unlike other measures such as LGBTQ+ and disability status, which are not typically captured by human resources, and (2) in the study we found ethnic and racial identification to be the variable for which the degree of homogeneity was related to the “intellectual leadership” aspect of the position (i.e., curator, conservator, educator, director). We are alert to issues of accessibility in this project, and although it was not foregrounded in our original project plan we hope to address these questions in more depth in future projects. ↑

Attribution/NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of the license, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.