Legacy Missions in Times of Change

New Issue Brief on Library Collections

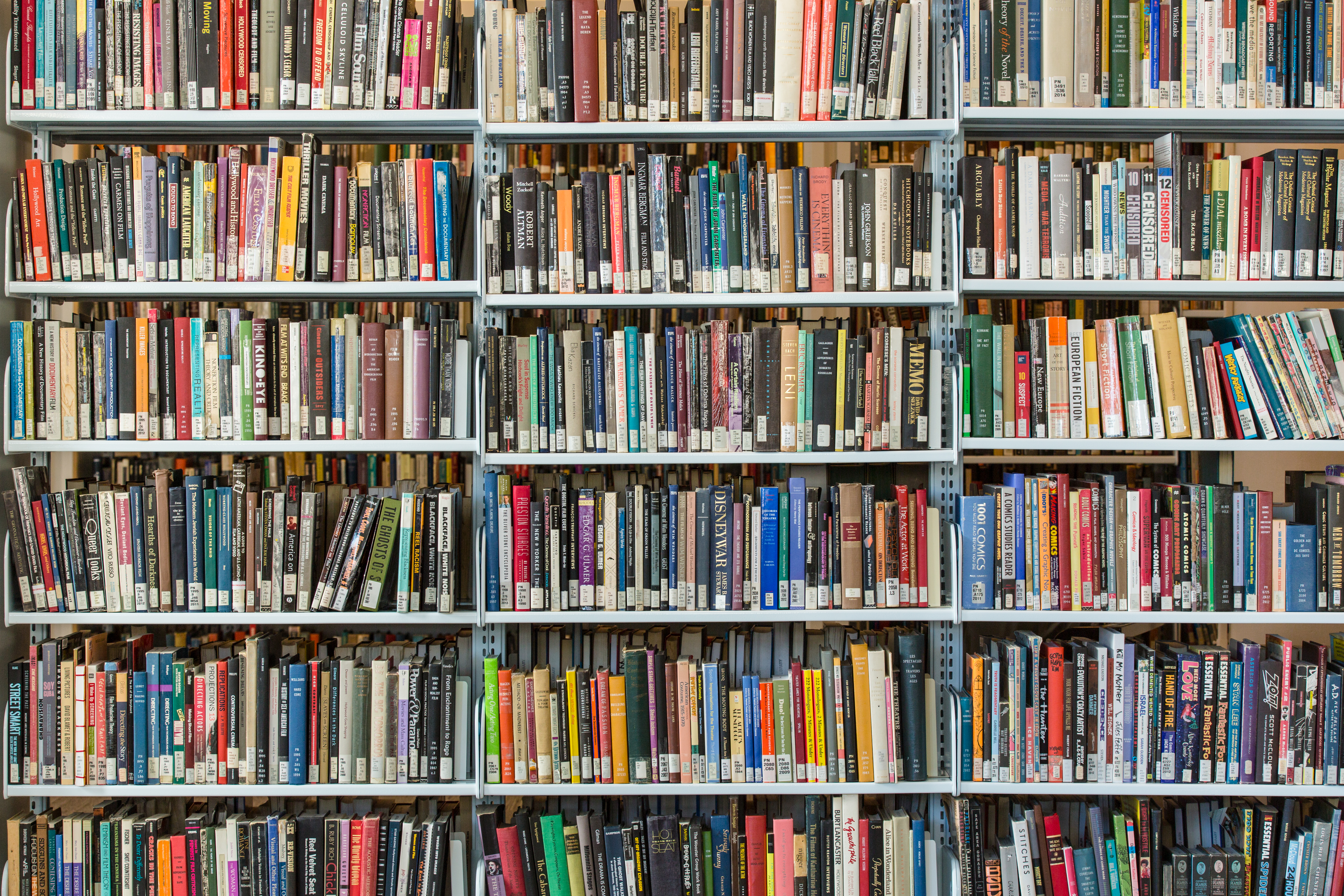

Regardless of the rapidly changing information and technology landscape, collections continue to be at the heart of academic libraries, signifying their role in providing access to our cultural heritage. But in an increasingly networked, distributed, licensed environment, how do we define the library collection? What do collections imply? What is involved in building a collection? The purpose of the brief published today is to characterize the evolving nature of collections and to highlight some of the factors behind these changes and their impact on the notion of collections. It is a reflection on how collections are defined and what it means to build a collection or develop a collection policy given the current information ecology and trends in research and pedagogy.

There are numerous drivers behind the evolving notion of collections, including emerging scholarly communication patterns and user behavior. The scholarly record is becoming much more heterogeneous, variable, dynamic, and distributed. Over the last 25 years, we have shifted from an environment characterized by information scarcity with limited distribution channels to a landscape of information abundance involving a variety of networked resources, including the proliferation of open access resources. In response to the new information ecology, there is increasing interest in curating unique and special materials and envisioning collections without institutional boundaries. Beyond licensing or purchasing digital resources, library staff now need to consider and plan for access contingencies to ensure that new content can be put in use and integrated with scholarly workflow tools. For instance, what would be the value of licensing a new database unless the library puts in place a support system with the required software for analysis and user assistance? Although still valued, the prominence of print collections are declining as a vast majority of academic library materials budgets are spent on licensing ebooks, ejournals, databases, and other online content. These are just some of the factors that contribute to the existentialist questions about the future of collection programs.

The library community is engaged in thoughtful deliberations to chart a new course that will align local collection strategies with the mission and priorities of their parent institutions and facilitate discovery and access. However, introducing and implementing a new collection paradigm is easier said than done due to structural issues, engrained expectations, reliance on incremental change strategies, and limited resources. How do we revamp and rebrand the concept of collections within the new information ecology? How do we characterize collections in order to articulate both the enduring and new roles libraries provide to their constituents? We hope that this brief will lead to further reflections on such critical questions. We look forward to hearing your comments about the future of collections.

Comments

The concept of "building a collection" grew from a time when discoverability and access to (print) materials that the library didn't already have within its walls was difficult and slow. That's not the world we work in today. Since no library can own everything,the concept of "a collection" implies selection - what will be of value to the institution long term and what will not. That in turn implies stability of demand on a scale of decades or more, which seems to be an article of faith among some librarians, despite being an empirically testable hypothesis. I have not seen any data that compels adherence to that belief, even though such data would not be too difficult to compile with today's digital tools.

Thanks for your comment, Melissa. Given how the information ecology and user behavior are evolving, i wonder if it is becoming increasingly difficult to project long-term curation goals (future users’ needs).