Moving Innovation Off Campus

When Paul LeBlanc arrived at Southern New Hampshire University in 2003, he realized that the small, private, tuition-dependent college on the banks of the Merrimack River was destined to decline right along with the downward projections for high school graduates in the state.

“I studied the cards we were dealt and looked for the best ones,” he said.

In one corner of campus, he found his ace in the hole: a small online operation. Over the next several years, by moving it off campus and hiring new talent from the corporate world, he watched as the university grew into the largest online provider in New England with more than 21,000 students and $118 million in revenue and a total budget of more than $200 million.

But by 2011, with a slowdown in online enrollments nationwide, LeBlanc was worried about what was to come next. So he created an “innovation team,” with the task of developing a model that could put the university’s online operation out of business. A little more than a year later, that team created a new competency-based program, called College for America, with degrees that are a fraction of the cost of those in the online program or four years at the traditional campus.

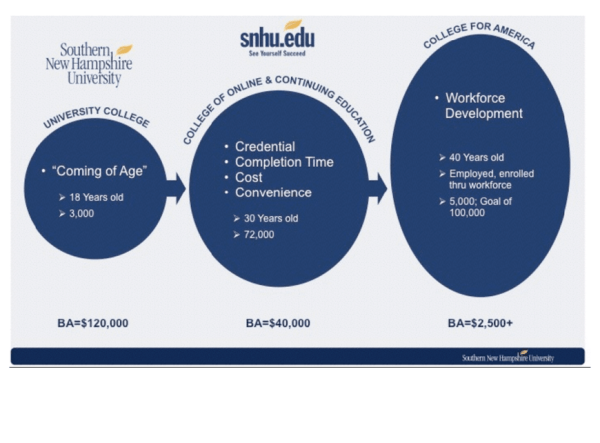

Today, Southern New Hampshire operates essentially three universities—traditional campus, online, and competency-based—with three different business models under one umbrella. Each one serves a different segment of students at varying price points, and with different missions and ambitions of scale.

The success of Southern New Hampshire has been well reported in the media, and LeBlanc is a regular on the higher-education conference lecture circuit. But what is often lost on those trying to simply replicate what Southern New Hampshire has done is how the university created the successful new entities.

Innovation is a hot topic on college and university campuses right now, and the conversations often lead to debates over shared governance and a university’s mission. Those conflicts come about because many institutional leaders are trying to change from within the current structure and shift a model their campuses have followed for much of their history.

At Southern New Hampshire, both its online operation and College for America were largely built off the main campus with a mix of people from the university and new hires. That enabled them to think differently and not try to innovate from within the legacy residential structure, its culture, or shift that mission, which Southern New Hampshire continues to serve. And one byproduct of the online program and College for America was that they protected and even strengthened the traditional campus with new revenue.

Building something new outside of the university also made strategic sense because Southern New Hampshire was hoping to serve new audiences it didn’t cater to in the past. Rather than try to retrofit what it was already offering on its traditional residential campus, the university built delivery systems that specifically tailored offerings to the needs of students with different motivations than traditional 18-year-olds who enrolled at the physical campus.

College for America, for instance, started with the idea that the degree shouldn’t cost more than $2,500 a year and that students would be recruited largely through partnerships with employers. Today, College for America has enrolled several thousand students and has its own mission statement distinct from that of its parent university.

Along with Southern New Hampshire’s online program, the early success of the competency-based program shows that perhaps the best path forward for universities to bring innovative ideas to fruition is one that doesn’t try to shift the direction they’ve already been traveling but rather builds a new path altogether.