The Value of Collective Impact for Higher Education Institutions

Over the past decade, collective impact initiatives have emerged in cities and communities all across the country. Collective impact refers to a cross-sector collaboration which brings together a broad spectrum of organizations to solve a specific social problem in a community. Collective impact efforts are typically geographically-bounded, to either a city, county, or region, and are different from traditional collaboration in that they are designed to drive sustainable change in entire systems. In addition to the organizations that work within the space, a “backbone organization” (typically an independent non-profit) takes on the task of facilitating the initiative’s working groups, collecting and analyzing community-wide data, and disseminating results to all partner organizations.

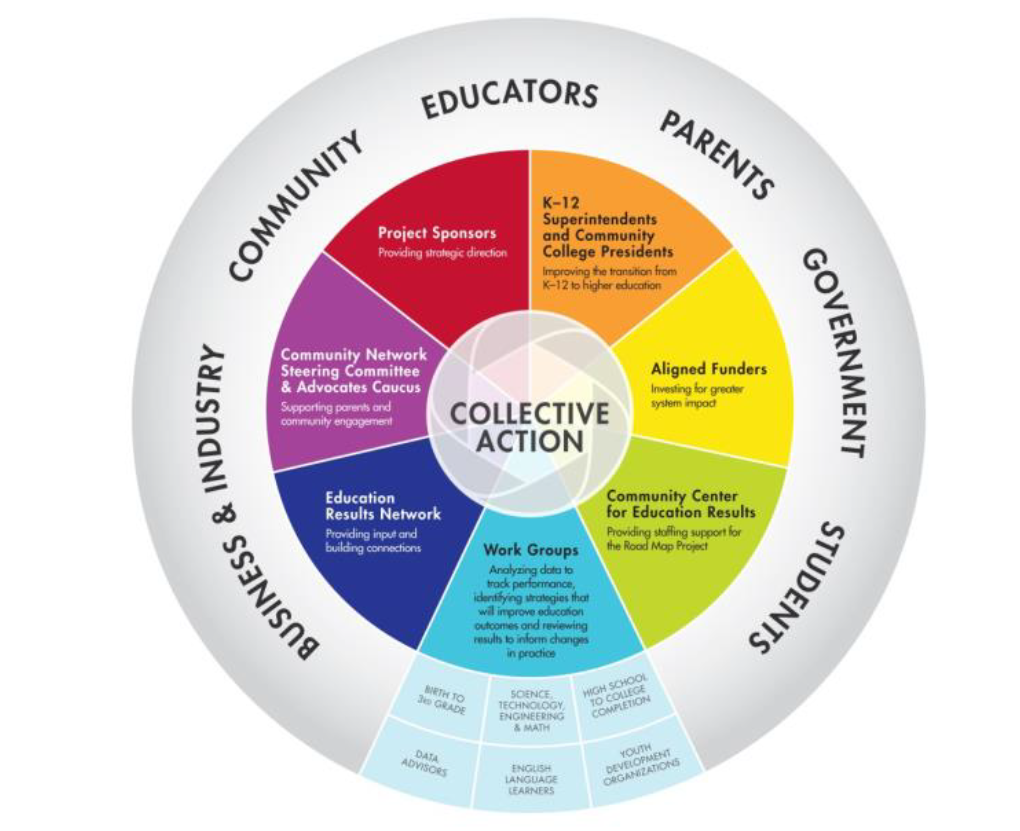

In education, collective impact initiatives promote better collaboration across early childhood, K-12, and post-secondary education actors, as well as other public sector, philanthropic, private, and non-profit service providers (see a stakeholder map example from Seattle’s Road Map Project).

Example of PK-16 Collective Impact Organization. Source: FSG, “Collective Impact Case Study: The Road Map Project,” p.3.

Collective Impact in Action: Cincinnati and Seattle

A great example of an education collective impact initiative is the StrivePartnership, which pioneered their “cradle-to-career” initiative in Cincinnati in 2006. In the decade since, this PK-16 organizing model has caught on nationwide, with over 70 different communities now part of the StriveTogether community of practice. (For full disclosure, I partnered with StriveTogether over the past year for my masters’ thesis, so I’m most familiar with PK-16 initiatives that are a part of their network, but I’ve included examples of other initiatives in this post as well, where relevant).

What results has the StrivePartnership delivered for Cincinnati postsecondary students thus far? Across the four local postsecondary institutions which participate in the partnership, postsecondary preparedness rose an average of 18.5 percentage points and retention rose an average of 4 percentage points since joining the collective impact initiative nine years ago. At the two local universities, the six year graduation rate rose by 19 percentage points over the same time period. It’s possible that these improvements in student outcomes might have occurred without the presence of the Cincinnati initiative, but the historical trend itself is undeniable.[1]

As part of the greater Seattle collective impact initiative, four community and technical colleges joined together to provide intensive advising to over 8,000 postsecondary students through Project Finish Line.[2] Since the multi-institution effort began three years ago, more than 1,000 students have earned their associate’s degree or credential. While we can’t say that the collective impact initiative necessarily caused these students to earn their degree or credential, the coordinated advising efforts of Seattle’s community and technical colleges are associated with improved two-year student outcomes. Additionally, the greater Seattle initiative’s community-wide efforts also led to a doubling of FAFSA submissions,[3] specifically for Seattle high schoolers who have signed up to participate in the state college promise program, directly impacting college affordability for this cohort of low-income, high-achieving students.

Despite the growing popularity of PK-16 collective impact initiatives, it is important to note that collective impact as an organizing model has not yet been rigorously evidence-tested, nor is it grounded in existing literature on community change. Many communities, including Seattle and Cincinnati, have seen specific educational outcomes improve after adopting a collective impact approach, but several successful case studies are not equivalent to a rigorous evidence base of effectiveness.

Value for Higher Education

As the Seattle and Cincinnati initiatives illustrate, higher education institutions can effectively move the needle on local postsecondary student outcomes—and achieve other important goals— through collective impact efforts. Collective impact’s value proposition for higher education lies in three primary areas:

1. Collective impact can reinforce institutional mission

Due to greater awareness and policy changes, higher education institutions are increasingly focused on completion and other measures of student success. Better coordination with the K-12 system can yield benefits that reinforce this mission. By coordinating with high school principals and counselors through the Albany Promise initiative, senior administrators at University at Albany developed a shared “early warning” system and created a community-wide summer advising program, making a major dent in summer melt for Albany’s low-income, minority incoming college students. University at Albany financial and admissions staff, along with others in the Albany initiative, held open office hours at local libraries and high schools for any recent graduates with questions about college enrollment and successful matriculation.

Collective impact initiatives also exist for other social policy issues. In addition to PK-16 and cradle-to-career initiatives, collective impact efforts also focus on workforce development, public health, and environmental cleanup, to name a few. Trade-focused community colleges may benefit from engagement with workforce development initiatives. Schools of public health may provide their students with a unique experience through engagement with community-based public health initiatives.

2. Collective impact can focus and strengthen institutional community engagement efforts.

Actively engaging with and supporting existing collective impact initiatives makes clear to community residents and leaders that a higher education institution cares about the issues that matter to them. Collective impact initiatives, by design, have already defined a given community problem, like PK-16 education, and decided communally how best they will address it. By committing to the collective impact effort, higher education leaders show community leaders they are in touch with and supportive of the collective “agenda.”

For example, working through the Commit! Partnership, 13 Dallas-based higher education institutions and four Dallas-based K-12 districts worked together to develop a text message-based advising app to reduce Dallas high schoolers’ summer melt, a problem identified using community-wide data from all K-12 partner districts. Over 2,000 students used the messaging app in 2015-16, connecting them directly to financial aid and admissions officers at the network of local postsecondary schools. Recent data suggest that after the first year of the texting program, over half of the participating high schoolers successfully enrolled in college, as compared to only 34% of non-participating students (though note, this was not a randomized control trial). By connecting their financial aid and admissions officers to the initiative’s advising app platform, this group of postsecondary institutions was able to provide targeted support to the students who needed it most.

3. Collective impact efforts can facilitate community-based research

Research universities, particularly those with public policy and/or education graduate programs, might be able to help support the shared measurement efforts of PK-16 collective impact initiatives, through qualitative research and surveys. George Washington University’s education faculty, for example, worked with the Raise DC initiative to design and conduct a qualitative study of DC “turnaround” high school students who were at risk of dropping out. By partnering with the collective impact body bilaterally, or through existing research consortia, postsecondary institutions can advance their research goals and support community-based solutions simultaneously.

By participating in collective impact initiatives, higher education institutions can better serve their own students, improve campus-community engagement efforts, and ultimately strengthen the communities in which they operate.

[1] Author’s calculation based on data presented in Strive Report p. 16-17. Data is from the Strive Partnership 2014-15 Annual Report, http://www.strivepartnership.org/sites/default/files/kw_partnership_rpt1014_v11_0.pdf.

[2]The Road Map Project: 2016 Results Report, p.31.

[3]The Road Map Project: 2016 Results Report, p.27.

Pingbacks

Why Institutions are Using the Well-Being Model to Empower and Support Students | Presence