Free for All: Contemporary Arts Museum Houston

Upon its founding in 1948, the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston (CAMH) was the first museum devoted to contemporary art in the region. Since its inception, this 16,000 square foot gallery, located between the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH) and Rice University, has responded to its rich environmental context. Houston has long been known for its remarkably diverse population, as well as its contributions to civil liberties, from Smith vs. Allwright in 1944, which ended the common practice of “white primaries” in the Democratic Party,[1] to Lawrence vs. Texas, which struck down sodomy law in Texas and 13 other states.[2] These are just some of the legacies CAMH engages with as it strives to be a hub in the region for contemporary art, both introducing international artists to Texas and serving as a home for local artists.

A non-collecting museum, or kunsthalle, CAMH has a history of producing provocative and compelling contemporary art exhibitions. In its early years the museum featured well-established modernist artists like Vincent van Gogh, Joan Miró, Alexander Calder, and Max Ernst, as well as local artists like John Biggers and his students at the historically black Texas Southern University. Mark Rothko and Robert Rauschenberg also had early shows at the museum. CAMH’s willingness to present challenging and provocative exhibitions and its focus on artists has given it a reputation within Houston as a cutting-edge venue for local, national, and international contemporary art.

Key Findings

The three-day site visit to the museum included 12 interviews, participant observation, and attending current exhibitions. Over the course of the visit some key findings for how the museum creates a diverse, equitable, and inclusive environment at the museum emerged:

- Youth Development: Through their Teen Council, CAMH fosters diversity by empowering youth.

- Language: In a city with 40 percent Spanish speakers, CAMH has committed to bilingual text in their shows and tours.

- Free Admission: CAMH is free for everyone. This removes a major barrier to entry for low-income visitors. It also allows the museum to curate with, at times, more diverse and more challenging content.

Challenges and Tradeoffs

The museum faces some difficult challenges and has had to make tradeoffs to achieve a more diverse, equitable, and inclusive environment:

- Sustaining a non-collecting museum: Lack of board diversity and perspectives of CAMH as “lean” and “scrappy” create sustainability challenges for the museum.

- Losing a Champion: The small museum has struggled to adapt after losing a strong curatorial voice with a vision for showing diverse contemporary artists.

- Measuring Diversity vs. Respecting Privacy: Privacy concerns prevent CAMH from seeking demographic data from its audience. Instead it relies on a culture of inclusion.

History and Context

The largest metropolis in Texas and fourth most populous in the United States, Houston is a sprawling city near the Gulf of Mexico.[3] In many ways, Houston’s complex history reflects many of the nation’s broader challenges. The city came to prominence at the turn of the 20th century, when a devastating hurricane struck the neighboring port city, Galveston. In 1900, a 15-foot storm surge swept over Galveston, which is only eight feet above sea level, ending a period of industrial growth for the city, with investors instead turning their attention towards Houston.[4]

In the first half of the twentieth century Houston grew tenfold. World War II transformed Houston, as it did so many American industrial hubs. The city became a major producer of munitions, steel, and naval ships. While many of these industries faded after the war, the substantial African American and Latino populations that were drawn to the city for high paying manufacturing jobs remained. The middle of the twentieth century saw the rise of Texas Medical Center and NASA’s Johnson Space Center. To this day, the city has a strong industrial base, with prominent oil, energy, aeronautics, manufacturing, and transportation sectors. Port of Houston is, by some measures, the largest in the country.[5]

In recent years its growth has been unprecedented; the Houston metropolitan area added 1.8 million people between 2000 and 2010, growing by about one-fifth. The city is now considered by some measures the most diverse in the nation.[6] The non-Hispanic white population and the African American population each make up roughly one quarter of Houston’s population. The Latinx population is 44 percent, and the Asian population is six percent.[7]

If Houston is a concentrated example of national demographic trends, it also reflects national trends in wealth disparity.[8] Houston households categorized as low income increased from 12 percent in the 1980s to 18 percent in 2010. Meanwhile, upper income households have doubled over the same period, from three percent in the 1980s to six percent in 2010.[9] Moreover, Houston is the most segregated city in the country by income. Over the last forty years, segregation by income has occurred in Houston at a much higher rate than any other U.S. city.[10]

As a non-collecting museum, CAMH occupies a unique position in the cultural landscape of Houston. Of the 222 North American AAMD members, only 11 identify as non-collecting. In practice this means museums like CAMH have a higher degree of flexibility to present ambitious and provocative shows than their collecting counterparts. “CAMH is either the littlest of big cultural organizations in Houston, or the biggest of the little,” says director Bill Arning, who has been leading the museum since 2009. One of the most valuable qualities for CAMH is this flexibility. In Houston’s dense Museum District, composed of 19 museums including the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Rothko Chapel, Menil Collection, Houston Museum of African American Culture, and Houston Center for Contemporary Craft, among others, CAMH must be deliberate to identify its role. Without a collection to build, study, and maintain, CAMH is free to commit itself to presenting contemporary art that is urgent and sometimes provocative. As former CAMH senior curator Valerie Cassel Oliver put it, the non-collecting museum is special because “we are writing history as it happens, we’re not required to follow established narratives.”[11] Oliver says this allows the museum to “present new modes, new practices, and innovations in the field. We’re not following the buzz, but rather keying into artists and practices that are changing the landscape. We find the artists who are catalysts of change. It allows us to think differently about history and materials.”

Staff Diversity

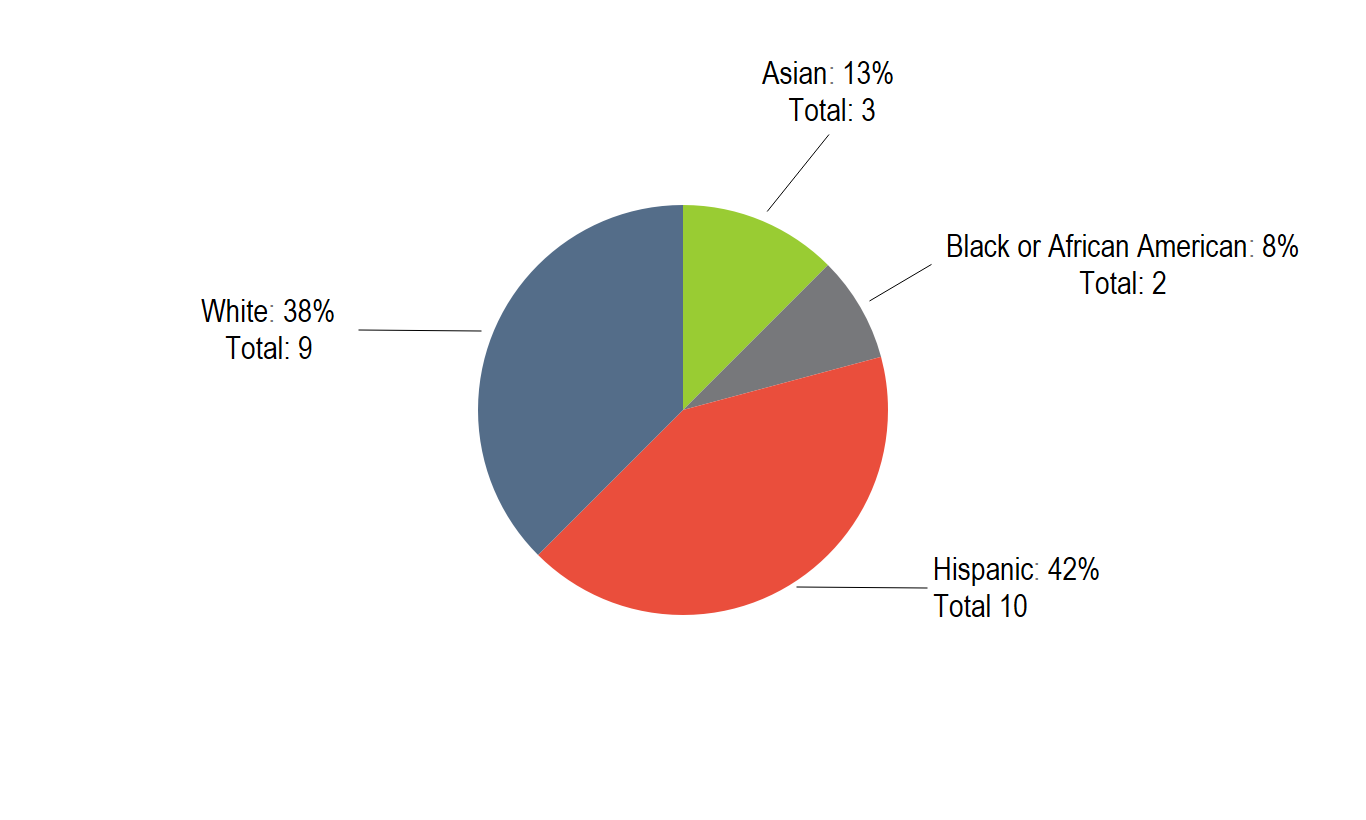

In terms of staff diversity, CAMH is among the eight percent of the 277 participating museums for whom people of color compose over half of the “intellectual leadership” positions, defined as curatorial, conservation, education, and senior administration.[12] As Figure 1 shows, Hispanic staff account for 42 percent of these positions, reflecting a plurality similar to that of the city of Houston.[13]

Figure 1: Contemporary Arts Museum Houston – Curators, Educators, Senior Administrators (2015)

Many of the Hispanic staff are part of the education department. Spanish fluency is a valuable asset in the department, particularly in a city with 1.3 million Spanish speakers.[14] Only about five percent of the museums included in the Mellon Foundation’s demographic survey had over 40 percent Hispanic staff in intellectual leadership positions.

Several interviewees expressed that more important to CAMH’s identity than racial/ethnic diversity was the embrace of Houston’s subcultures. YET, a Hispanic performing artist and member of CAMH’s FAQ Team (a group of local artists and makers who provide public tours of the galleries), described the welcoming feeling that CAMH has cultivated with staff: “What I love about this place is that not only is [CAMH] diverse in ethnicities, but also diverse in fashion choices—you’re not judged by your identity. All are treated equally. I think that’s a lovely thing we have here, because you can walk into the museum and one of our guards has green hair, and the arts administrator has bright yellow hair. Everyone is tattooed and delivers a high quality of work. I feel like certain other institutions aren’t as open.” This is in contrast to the atmosphere YET experienced at another art museum in Houston: “I remember being told that I couldn’t look how I looked and teach, I was told, ‘If you’re tattooed, you can’t do this.’ I’ve been asked to remove a nose piercing while providing a birthday tour.” It is important to YET that this would not occur at CAMH. This perspective is aligned with a broader sentiment among staff interviewees, several of whom describe the city as being composed of many subcultures. Embracing these communities has become central to CAMH’s identity.

The FAQ Team, which provides CAMH’s gallery tours, and whose members are often working artists, critics, and art historians themselves, has achieved a high level of diversity. YET explained that the FAQ Team is empowered to make recommendations when vacancies arise. That approach has yielded a diverse FAQ Team staff and an inclusive atmosphere, according to members. The museum has adopted a similar approach with its Teen Council, whose members are roughly 85 percent people of color.

Youth Development

The CAMH Teen Council is a youth development program that has been in place since 1999. Serving local youth, Teen Council introduces members to the field of contemporary art, offering exposure to the art world, visual literacy, and work experience. Members meet weekly and are invited to see the inner workings of the museum and the broader arts environment in Houston by organizing and participating in art markets, exhibitions, fashion shows, film screenings, listening parties, music festivals, or poetry readings. As was revealed in an in-depth analysis of the program through the Whitney Museum of American Art’s publication Room to Rise,[15] Teen Council has managed to solidify among many participants a lifelong commitment to advocacy for contemporary art and its place in society. Michael Simmonds, Teen Council and public programs coordinator, says the program “gives teens a sense that there are more options than just artists and curators when considering arts careers.”

Teen Council also gives the teens valuable workplace experience early in their professional lives. Similar to the FAQ Team, Simmonds explained that the museum lets the participants make decisions about how to recruit the next cohort: “We do advise them to think about diversity. First, we don’t want all students to be from the same school, and we also want diversity of ages, and diversity of interests.” The high degree of racial/ethnic diversity that this yields reflects that of the young population of Houston.

In the IMLS funded publication Room to Rise, researchers at the Whitney Museum of American Art conducted an assessment of the impact of several youth development programs, including CAMH’s Teen Council.[16] They did so by following up with former members of these programs, conducting interviews, and collecting self-evaluations related to the impact these programs had on the individual’s career trajectory and relationship to the arts. This useful evaluative work captured the impact the Teen Council program had on the lives of its participants in their own words.

For instance, Teen Council participant Ciarán Finlayson’s academic and career path has taken him from the program, through college and internships with museums and cultural organizations, to graduate work in aesthetics and art theory. He says, “I was told that I was appointed in large part [to my current role] because the work I had done as an intern at CAMH was exactly what they wanted me to do at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. […] I would likely not be doing any of the things I do every day had I not been selected for Teen Council.” Between the experience Finlayson gained through the Teen Council and access to the museum’s network, the program led to two internships. Access to CAMH’s exhibitions was, as Finlayson notes, “instrumental in the development of my political consciousness and in my thinking about blackness.” Finlayson went on to pursue graduate studies in aesthetics and art theory at Kingston University in London.

Another CAMH Teen Council participant said, “In my high school, I was the only student considering going for a Bachelor of Fine Arts. The Teen Council was my only contact with other young artists who helped me compare and contrast college choices that my high school counselor knew only a little about. After choosing to attend Tisch School of the Arts at New York University, my experience at the Teen Council influenced my desire to continue to work within art institutions.” And another Teen Council participant said, “I really believe my time on the CAMH Teen Council shaped who I have become as an adult. I came to art school after graduating high school with a much richer knowledge of contemporary art than many of my classmates. Many of my professors noted this in my first year of undergrad. I also still love museums and work and volunteer in them to this day.”

These accounts do much to illuminate the value of such youth development programs, and underscore the importance of encouraging diversity within them. With the highly diverse Teen Council, CAMH is making a meaningful impact by preparing the next generation of artists, curators, and arts administrators, as well as lifelong museum visitors.

Exhibition Program

For the last 17 years, CAMH has enjoyed the expertise of Valerie Cassel Oliver, a curator who has been influential in the process of revising the canon of contemporary art to include underrepresented groups. With her recent departure, CAMH’s small curatorial department has had to grapple with a challenging question: how to adapt to the loss of a champion for equity and inclusion.

Oliver is a native Houstonian, and CAMH played a central role in developing her interest in contemporary art. She sees her contribution to the museum as part of an impressive exhibition history that influenced her own career: “It’s a celebrated institution in Texas-locally, regionally and statewide. For decades it was the only museum dedicated to contemporary art in Houston. Fortunately, it has retained its focus of presenting the cutting edge of art making and risk-taking.” From Oliver’s point of view, CAMH has been a leader in the region in presenting contemporary art. Significant exhibitions over the last several decades have included Dále Gas: An Exhibition of Contemporary Chicano Art (1977), Rauschenberg/Performance 1984, Abstract Painting, Once Removed: A Fiftieth Anniversary Exhibition 1998, Double Consciousness: Black Conceptual Art Since 1970 (2005), and Parallel Practices: Joan Jonas & Gina Pane

(2013).

Oliver began curating at CAMH shortly after co-curating the 2000 Whitney Biennial. She produced a number of exhibitions representing the contributions of African American artists, such as Double Consciousness: Black Conceptual Art Since 1970 (2005), Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art (2012), and Cinema Remixed and Reloaded: Black Women Artists and the Moving Image (2008).[17]

But her work at CAMH was not tied specifically to any racial or ethnic group. Continuing in the tradition of bringing emergent or overlooked artists to the fore, Oliver’s last show before assuming her current post as the Sydney and Francis Lewis Family Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA) brought attention to a master of contemporary ceramics. The first major survey of Annabeth Rosen’s ceramic sculptures, Annabeth Rosen: Fired, Broken, Gathered, Heaped (2017) was on view during the site visit in October, 2017. Rosen experiments with ceramics, often building sculptural forms by binding many discrete objects with variations to create large figurative or geometric sculptures.[18] In this survey, Oliver offers a long overdue correction to the contemporary art landscape, elevating a ceramicist who has been overlooked.[19]

Annabeth Rosen: Fired, Broken, Gathered, Heaped (installation view), 2017. Photo by Gary Zvonkovic. Courtesy of the artist and the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston.

Patricia Restrepo, exhibitions manager and assistant curator, expressed the caution with which CAMH is looking to fill the vacant position of senior curator: “We find ourselves in a conundrum, while we want to diversify staff, we’re not interested in just hiring a token replacement, we want a genuine hire.” As deputy director Christina Brugardt said, “We were very lucky to have Valerie at CAMH. She is a marvelous scholar and curator. She has a great national presence and is a Houston native. And she inherently understood community outreach.” Oliver’s absence was especially noteworthy as it so immediately preceded the site visit—she had left just two weeks prior. It is indeed daunting to replace such a prominent curator of color. From data gathered in the 2015 demographic survey, we know that out of 1,365 curators, only 29 of them were black or African American. However, each new opening creates an opportunity for new talent to enter the field. By thinking broadly about job qualifications and networking aggressively, CAMH has an opportunity to foster a new voice in Houston’s museum district.

This loss by no means has prevented the museum from pursuing impactful and intelligent shows that connect to underrepresented communities. Many of its forthcoming shows aim to give voice to underrepresented groups. For instance, in August 2018, CAMH will feature Walls Turned Sideways: Artists Confront the American Justice System. Given that Texas incarcerates more prisoners than any other U.S. state, this exhibition on the prison industrial complex is particularly relevant. Another exhibition, Right Here, Right Now: San Antonio, is the third iteration of a series of shows that examine art in the region, and includes mainly Hispanic artists. The museum continues to bring in international viewpoints as well. For the museum’s submission to FotoFest, an international photography biennial in Houston, CAMH has organized Dissent and Desire, a show of collaborative photographs by artists Charan Singh and Sunil Gupta. The work explores LGBTQ narratives in India, a community that has faced explicit state oppression in recent years.[20]

Such exhibitions are the norm at CAMH, which identifies as a progressive institution, introducing Houstonians to global trends in art, culture, and social justice, while also serving as a site for urgent and provocative content that addresses the social and cultural issues of the region.

As of this year, all of the brochures and wall-text at CAMH are bilingual, a development that helps the museum serve the large Spanish speaking population of Houston. Director Bill Arning has his sights set on turning CAMH trilingual, with hopes of connecting to Houston’s Vietnamese population. Additionally, the museum has begun offering sign language tours. Arning says the practice has brought a new community to the museum, indicating that the tours have been fully booked. He also recognizes that there is value in the practice, attendance notwithstanding: “A city’s contemporary museum has to be radically inclusive at all times. Even if we don’t have anyone deaf in the audience, having a sign language interpreter shows this is an inclusive place.”

Free for All

As visitors enter the museum, many stop at the attendant desk to ask the cost of admission. As deputy director Christina Brungardt said, “Everyone gets excited about walking in the door, and hearing ‘we are free.’ There’s a sudden excitement when they realize that they can come and go. Sometimes we show things that are bizarre and awkward. Because it’s free people don’t feel upset, they feel they can walk away if they want to.” Brungardt acknowledges that this approach is in opposition to the feeling of exclusivity sometimes cultivated in more traditional galleries. Exclusivity is decidedly not the atmosphere CAMH seeks to foster.

The diversity of CAMH’s visitors is a source of pride in the city. As Debbie McNulty, director of Houston’s Department of Cultural Affairs, said, “Personally, it has been a joy to come here and see attendance look like our city.” In a series of interviews with museum visitors, there was a consistent refrain that they felt the museum was an inclusive environment. One Native American visitor said she learned about the museum through an email promoting free things to do in Houston. She explained that she felt comfortable at CAMH because of the people it attracted. “I like art because of the open-mindedness,” she said. “I feel comfortable and welcome here. I feel free in the museum. It’s because the people who make the art have to be free.” Another visitor from Puerto Rico (during Hurricane Irma) described herself as an art lover and explained, “I like Annabeth. Not to say I understood all of it, but I like it. I feel comfortable here.”

As Michael Simmonds, Teen Council and public programs coordinator said, “Being a free museum defines us. It’s so important that we be accessible to anyone who comes through the doors. But we’re not afraid of putting up challenging content.” Felice Cleveland, director of education and public programs, previously worked at two museums that charged admission fees at the door. She explained that much of her efforts at CAMH are to raise awareness about the freely accessible contemporary art exhibitions for the broader public: “For me, the long game is having students at a young age who are comfortable at a museum. Then they bring parents.” Free admission means Cleveland can start with the program when strategizing about outreach, she doesn’t have to worry about the barrier of an admission fee. As she describes, in her old museum positions “I was always really lobbying for a free day, or pay what you want. Here I don’t have to have that conversation. It’s easier to invite people here when it is free.” Free admission is built into the museum’s general operating budget, while the museum seeks a donor to endow the free admission policy in order to allow funds to be reallocated to exhibition and education expenses. In CAMH’s view, the income stream generated from charging attendance is not sufficient to justify the drop in attendance it would cause.[21]

Between free attendance, contemporary art offerings that connect with underrepresented groups, and the demographic diversity of Houston, CAMH has little trouble with audience diversity in terms of race and ethnicity, LGBTQ and, increasingly, people with disabilities. However, the museum does not measure these variables through assessments or survey instruments. “There’s a strong sense of sensitivity around demographic questions. We don’t want to ask people how they identify because it can seem invasive, but we realize that’s something foundations want to know,” said Brungardt. Instead, the museum approximates socioeconomic and race and ethnic categories using zip codes, a practice that would be less effective in a more integrated city.

Board

Cleveland recognizes that the museum’s environment plays a large role in its ability to maintain free admission: “I know from the price point of fund-raisers, Pittsburgh and Baltimore vs Houston, it’s just a different scale.” Houston ranks among the highest cities in America in terms of philanthropic giving.[22] And the city has among the highest number of Fortune 500 companies, second to New York.

Even so, a non-collecting museum faces some meaningful barriers to fundraising. While its neighboring museum, the MFA Houston has a net worth of around 1.5 billion dollars (and charges $15 for general admission), CAMH’s net worth is roughly 10 million dollars. “It’s very fragile now in terms of what it’s bringing in the doors and how it can sustain itself,” Oliver said. “I love that museum, but I’m worried about it. Beyond my hitting a professional ceiling, I also felt the resources weren’t there to do the work the museum wants and needs to do. The city loves to see it as scrappy and lean, but with so many competing interests from other Houston cultural organizations now engaging with contemporary art, I worry about people going to things that are shiny rather than sustaining the CAMH and its programming that has historically reverberated not only locally, but also nationally and internationally. They’ve got to take care of things like facilities. The administration building is literally falling down. Those things can’t be addressed without resources.”

Representational Diversity

At the moment CAMH has very little representation of people of color on the board. Arning is aware of the need to increase diversity on the board and has set a goal to bring five diverse candidates onto the board this year. “For the last few years, we’ve brought some diversity to the board through artist board members,” Arning explained. “But this doesn’t help us network with African American business professionals.” Arning is well aware that connecting with diverse philanthropic communities is about building networks, and in a recent board meeting observed that, for about two-thirds of board members, all of their children attend the same school: “Where the kids go to school is a big part of how these networks form.” At the moment, CAMH has three candidates of color who may possibly join this year.

Interviews with staff and city officials confirmed that, at present, the fundraising environment is very challenging in Houston. As the city recovers from Hurricane Harvey, many resources must be directed to humanitarian relief, as well as the performing arts sector, which was devastated by the hurricane.[23]

Conclusion

CAMH faces some challenges unique to a non-collecting museum, while other challenges will be familiar to the broader field. As CAMH works to diversify its board and raises funds for improvements to the museum’s infrastructure, it also must continue the work of revising the canon with new curatorial leadership.

The museum has succeeded in generating a casual, non-committal atmosphere through its ability to offer free admission to all visitors all the time. By cultivating a climate of open-mindedness, it has connected with the many subcultures of Houston, from noise musicians to fire breathers. Through its exhibition program it has been able to address myriad issues in public discourse, from global LGBTQ rights to American mass incarceration. And with its youth development program Teen Council, CAMH is able to prepare a diverse set of emerging professionals to pursue careers in the cultural sector. The museum has done much to bring urgent contemporary art to the city of Houston, and to bring the diversity of Houston into the museum.

Appendix

Case Studies in Inclusion, Diversity, and Equity among AAMD Member Art Museums

Three years ago, Ithaka S+R, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD), and the Alliance of American Museums (AAM) set out to quantify with demographic data an issue that has been an increasing concern within and beyond the arts community: the lack of representative diversity in professional museum roles. Our analysis found there were structural barriers to entry in these positions for people of color. After collecting demographic data from 77 percent of AAMD member museums, we published a report sharing the aggregate findings with the public. In her foreword to the report, Mariët Westermann, executive vice president for programs and research at the Mellon Foundation, noted, “Non-Hispanic white staff continue to dominate the job categories most closely associated with the intellectual and educational mission of museums, including those of curators, conservators, educators, and leadership.”[24] While museum staff overall were 71 percent white non-Hispanic, we found that many staff of color were employed in security and facilities positions across the sector. In contrast, 84 percent of the intellectual leadership positions were held by white non-Hispanic staff. Westermann observed that “these proportions do not come close to representing the diversity of the American population.”

The survey provided a baseline of data from which change can be measured over time. It has also provoked further investigation into the challenges of demographic representation in this sector. Many institutional leaders are growing increasingly aware of demographic trends showing that in roughly a quarter century, white non-Hispanics will no longer be the majority in the United States, whereas 10 years ago the white non-Hispanic population was double that of people of color.[25] This rapid growth indicates that institutions will need to be intentional and strategic in order to be inclusive.

To aid these efforts we set out to understand the following: What practices are effective in making the American art museum more inclusive? By what measures? How have museums been successful in diversifying their professional staff? What do leaders on issues of social justice, equity, and inclusion in the art museum have to share with their peers?

Using the data from the 2015 survey, we identified 20 museums where underrepresented racial/ethnic minorities have a relatively substantial presence in the following positions: educators, curators, conservators, and museum leadership. We then gauged the interest of these 20 museums in participating, also asking a few questions about their history with diversity. In shaping the final list of participants, we also sought to ensure some amount of breadth in terms of location, museum size, and museum type. Our final group includes the following museums:

- The Andy Warhol Museum (Pittsburgh)

- Brooklyn Museum

- Contemporary Arts Museum Houston

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago

- Spelman College Museum (Atlanta)

- Studio Museum in Harlem.[26]

We then conducted site visits to the various museums, interviewing between 10 and 15 staff members across departments and levels of seniority, including the director. In some cases, we also interviewed board members, artists, and external partners. We observed meetings, attended public events, and conducted outside research.

In the case studies that follow, we have endeavored to maintain an inclusive approach when reporting findings. For this reason, we sought the perspectives of individual employees across various levels of seniority in the museum. When relevant we have addressed issues of geography, history, and architecture to elucidate the museum’s role and context in its environment. In this way we show the museum as a collection of people—staff, artists, donors, public. This research framework addresses the institution as a series of relationships between these various constituents.

We hope that by providing insight into the operations, strategies, and climates of these museums, the case studies will help leaders in the field to approach inclusion, diversity, and equity issues with a new perspective.

Endnotes

[1] Michael J. Klarman, “The White Primary Rulings: A Case Study in the Consequences of Supreme Court Decisionmaking,” Florida State University Law Review 29 (2001): 55.

[2] Darlene Clark Hine, Steven F. Lawson, and Merline Pitre, Black Victory: The Rise and Fall of the White Primary in Texas (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2003).

[3] Houston has the largest land mass of any major U.S. city, 627.5 square miles: “Population Finder,” American Fact Finder, U.S. Census Bureau, 2009, archived from the original on November 18, 2015.

[4] Paul Alejandro Levengood, “For the Duration and Beyond: World War II and the Creation of Modern Houston, Texas,” PhD diss., Rice University, 1999.

[5] Kiah Collier, “Houston Has the Busiest Seaport in the U.S.,” Houston Chronicle, May 23, 2013, accessed April 02, 2018, https://www.chron.com/discoverhouston/article/Houston-has-the-busiest-seaport-in-the-US-4486844.php.

[6] Brittny Mejia, “How Houston Has Become the Most Diverse Place in America,” Los Angeles Times, May 09, 2017, accessed April 03, 2018, http://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-houston-diversity-2017-htmlstory.html.

[7] The Kinder Institute for Urban Research, “The Shifting City: Houston’s History of Unequal Racial Change,” June 1, 2016, accessed April 3, 2018, https://kinder.rice.edu/research/shifting-city-houstons-unequal-history-racial-change.

[8] Over the last forty years the share of neighborhoods across the United States that are predominantly middle class or mixed income has been shrinking, from 85 percent in 1980 to 76 percent in 2010.

[9] Houston has a Residential Income Segregation Index (RISI) score of 24 percent.

[10] For the top 10 largest metros, the RISI score has increased for each one between 1980 and 2010. On average, the RISI score increased by 11 percent. Houston is an outlier in this respect, with a significantly larger increase than any of the other cities, at 29 percent (Dallas is the next closest at 21 percent).

[11] Valerie Cassel Oliver is now curator of modern and contemporary art at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA).

[12] Most of the museums that fall into this category are culturally specific; Roger Schonfeld, Mariet Westermann, and Liam Sweeney, “Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey,” The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, accessed April 18, 2018, https://mellon.org/programs/arts-and-cultural-heritage/art-history-conservation-museums/demographic-survey/.

[13] Overall staff are 55 percent white non-Hispanic at the museum

[14] Lomi Kriel, “Just How Diverse Is Houston? 145 Languages Spoken Here,” Houston Chronicle, November 06, 2015, accessed April 04, 2018, https://www.houstonchronicle.com/news/houston-texas/article/Houstonians-speak-at-least-145-languages-at-home-6613182.php.

[15] Danielle Linzer, Room to Rise: The Lasting Impact of Intensive Teen Programs in Art Museums (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2015).

[16] Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, Youth Insights (created in 1997), Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Contemporary Arts Museum Houston (CAMH), the Teen Council (created in 1999) The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA).

[17] Oliver’s first show at the VFMA has been announced for January 2019, featuring painter Howardena Pindell and co-curated with Naomi Beckwith of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago.

[18] Downstairs, the museum introduced the moving image work of Berlin-based duo Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz, Telepathic Improvisation (2017). A film installation responding to a score by German left-wing militant Ulrike Meinhof in 1968, the abstract movements of the film reference specific moments of leftist protest, queer S&M club life, and acts of surveillance, among other things.

[19] Cat Kron, “’ANNABETH ROSEN: FIRED, BROKEN, GATHERED, HEAPED’” at Contemporary Arts Museum Houston,” Artforum International, accessed March 23, 2018, https://www.artforum.com/print/previews/201705/annabeth-rosen-fired-broken-gathered-heaped-68001.

[20] Naisargi N. Dave, Queer Activism in India: A Story in the Anthropology of Ethics (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012).

[21] CAMH experimented with this approach several years ago but quickly reverted back to a free model.

[22] As measured by charitynavigator.org.

[23] Michael Cooper, “Hurricane Harvey Closes Houston’s Opera and Ballet Home for a Season,” The New York Times, September 19, 2017, accessed March 23, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/19/arts/music/hurricane-harvey-closes-houstons-opera-and-ballet-home-for-a-season.html.

[24] Roger Schonfeld, Mariët Westermann, and Liam Sweeney, “Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey,” The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, July 29, 2015, https://mellon.org/media/filer_public/ba/99/ba99e53a-48d5-4038-80e1-66f9ba1c020e/awmf_museum_diversity_report_aamd_7-28-15.pdf.

[25] William H. Frey, “A Pivotal Period for Race in America,” In Diversity Explosion: How New Racial Demographics Are Remaking America (Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2015), 1–20, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7864/j.ctt6wpc40.4.

[26] We focused on people of color for measuring diversity for two reasons: (1) In the 2015 art museum demographic study, we received substantive data for the race/ethnicity variable, unlike other measures such as LGBTQ+ and disability status, which are not typically captured by human resources, and (2) in the study we found ethnic and racial identification to be the variable for which the degree of homogeneity was related to the “intellectual leadership” aspect of the position (i.e., curator, conservator, educator, director). We are alert to issues of accessibility in this project, and although it was not foregrounded in our original project plan we hope to address these questions in more depth in future projects.

Attribution/NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of the license, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.