Preserving Their Stories

Making (and Sharing) Art Under Mass Incarceration

Introduction

The impacts of the criminal legal system extend far beyond prison walls, affecting families and communities physically, socially, and financially.[1] With millions of people locked up and hundreds of thousands leaving and entering prison each year, some estimates note that almost half of all Americans have experienced the revolving door of incarceration within their families.[2] Though the impacts of prison are fundamentally interwoven in the experiences of many communities, especially communities of color, mass incarceration in many ways remains invisible in the archival record and national consciousness and memory. Prisons, through their physical remoteness and control over interactions with the free world, render the people in their facilities invisible to the wider public. The stigma attached to incarceration further suppresses the sharing and documenting of people’s experiences of incarceration and how it affects their lives.

The invisibility of mass incarceration makes it challenging to understand and address in the present while imperiling future generations’ ability to fully comprehend and study it. Government agencies like departments of corrections (DOC) may produce a wealth of documentation, but the state’s view of its incarcerated subjects is inherently one sided. We are on less sure footing when it comes to documenting mass incarceration through the perspectives of those who have experienced it. This is not to say that such materials do not exist; a prison can be a vibrant locus of creative production, whether through theater, art, music, journalism, or creative writing.[3] The challenge is understanding how these materials are produced, how they circulate inside and outside of prisons, identifying where they end up, and determining how they might be ethically collected and preserved for both the present and the future.

While a handful of initiatives have recently begun to systematically collect materials created by people impacted by incarceration,[4] anecdotal evidence suggests that most incarcerated artists and writers entrust their work to grassroots and volunteer-led organizations such as prison arts initiatives and higher education in prison programs. Thus, if we are to begin to address archival silences around marginalized populations, in this case people who have experienced incarceration, it will be critical to understand the role community organizations can play in creating more inclusive and holistic collections and supporting humanistic inquiry. Because these organizations are not traditional “memory institutions” (museums, archives, and libraries), grassroots organizations face specific challenges in fulfilling that role. Such organizations lack the capacity and expertise to appropriately care for the materials entrusted to them and, as a result, this material is often left to languish in boxes and volunteers’ basements. It is therefore critical that work be done to ensure this rich body of material is not lost.

In this project, Ithaka S+R, in collaboration with Wendy Jason from the Justice Arts Coalition (JAC), a national organization that has provided numerous opportunities for incarcerated and formerly incarcerated artists to share their work,[5] set out to explore how grassroots organizations that support the arts in prison are fostering the creative enterprise of incarcerated people, including how they are providing arts programming within prisons and how they are receiving, collecting, preserving, and showcasing the art of incarcerated people beyond prison walls. Who are these organizations? What are their current practices? What challenges do they face? What ethical considerations shape the way they work with this vulnerable population?

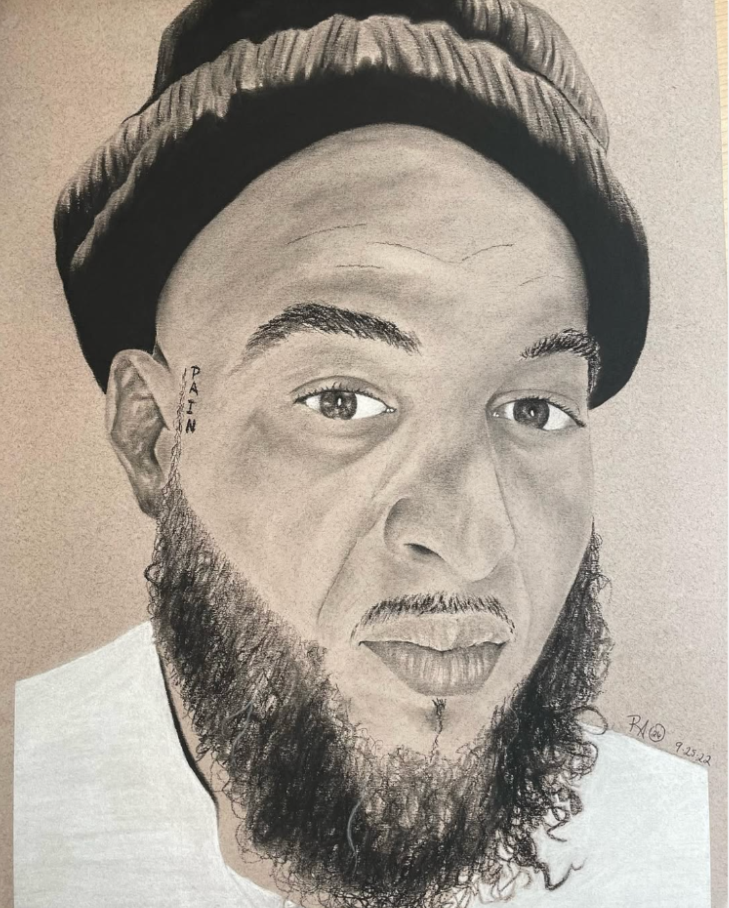

“Pain Looks Like This,” by Robert Odom[6]

How do they ensure that impacted individuals are part of the archival process and not exploited by that process? What resources, training, technology, and partnerships would help? Through desk research, qualitative interviews, and convenings, we have tried to answer these questions from the inside out; that is, beginning with the incarcerated artists themselves—how they create their work, what self-expression means to them, how they send their work outside—and expanding out to the organizations (and in some cases family members) that receive, share, and preserve that work.

Our longer-term vision is to lay the groundwork for future projects aimed at providing training and resources to community organizations that will enable them to not only better care for and make accessible the materials under their care, but also connect them to more traditional memory institutions that are interested in this material. We hope the evidence collected during this exploratory project is a catalyst for that more significant implementation. Too often, the narratives and public imagery that surround prison are shaped by media forces with little input from the directly impacted. Likewise, humanistic study of mass incarceration has been constrained by a lack of materials representing the perspectives of the incarcerated. In seeking to preserve and make accessible work created by incarcerated people, we believe that they will, in turn, be more able to shape the narratives told about them and legitimize their experiences as a critical part of the nation’s heritage and history.

Methodology

Between October 2023 and May 2024 we conducted semi-structured interviews with seven incarcerated and formerly incarcerated artists and 11 staff members of organizations gathering and archiving art from inside, as well as two DOC officials overseeing educational programming in their facilities. Participants were recruited through the networks of the Justice Arts Coalition (JAC) as well as via word of mouth and snowballing techniques. Interviewees were selected to ensure a broad representation of geographical areas and types of organizations, including prison education programs and grassroots and advocacy organizations.

While our long-term goal is to support organizations preserving different kinds of creative work, from fiction and non-fiction writing to music, for this project we decided to focus on documenting the experiences of incarcerated visual artists, and of organizations and individuals collecting their artwork on the outside. In part, this was due to the expertise and networks of our colleagues at JAC, but we also realized partway through the project that the conditions incarcerated visual artists face in practicing their craft, getting their artwork to people outside, and finding ways to preserve their creative work introduced a particular set of challenges worth exploring.

Interviews were conducted remotely, with each interview lasting between 45 and 90 minutes. In order to protect the privacy of our participants, particularly of incarcerated artists, and encourage them to share their experiences more freely, interviews were not audio-recorded, but detailed notes were taken during each conversation. All notes were stored in a password-protected drive, to which only Ithaka S+R researchers and JAC staff had access. As a form of compensation, and as a token of appreciation for their participation in the project, justice-impacted participants received a $50 honorarium.

All interview notes were analyzed using qualitative thematic analysis procedures, in which coding and sub-coding categories are derived iteratively from the data. After the coding process was completed we presented our findings to an advisory board including several experts in the field, including museum and letter archive curators, a formerly incarcerated artist, and a prisoner rights advocate, among others. Based on their feedback, we further refined our interpretation of the findings and coding categories.

Making art inside

All the artists we interviewed spoke of the value of practicing the arts while incarcerated—with many describing art as a powerful tool for healing and personal transformation, a way to gain consciousness and a “way out” of the dullness of prison life. One artist summed it up this way, “Art was my freedom.”

But as powerful as the act of creation can be and the positive effects it has on those inside, the obstacles, challenges, and even repercussions incarcerated artists experience just for practicing their craft can be equally daunting. From limited access to training opportunities, paltry art supplies, and almost complete lack of storage and workspaces, to institutional censorship and surveillance, there are multiple barriers they have to overcome even before their work can circulate outside of prisons.

Becoming an artist

Most of our interviewees began practicing their craft through self-teaching or peer-mentorships, thanks to serendipitous encounters with fellow artists inside, rather than through formal training. Greg Bolden—an author, artist, and poet who served 32 years in the Federal Bureau of Prisons—said that he always “had a knack for art, just didn’t know what to do with it.”[7] It was only after meeting some talented artists on the inside and witnessing the transforming power of art in their lives, that he committed to learn from them. Similarly, Matt,[8] who was incarcerated in Pennsylvania until his release in 2022, said he enjoyed drawing, and making portraits in particular, throughout his youth, but that it was only three years into his sentence that he “had an epiphany.” He began working to improve his technical skills and started to see himself as an artist.

Given the almost complete lack of formal classes and training opportunities inside prisons, for most people self-teaching and peer mentorship wasn’t a choice, but rather the only options, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic. William “Trey” Livingston,[9] for instance, an artist and musician who served a 13-year sentence in Oklahoma and had been home for just under two years when we met him, said the first facility in which he was detained, run by the GEO Group, offered almost no training or educational programming beyond some basic culinary classes and faith-based programs.

“Existing #1,” by William “Trey” Livingston

However, as others reported and the DOC representatives we spoke with confirmed, even in better-resourced facilities, art classes with outside instructors were few and far between. Even when there is a willingness on the part of DOC leadership to bring in arts programming in state facilities, institutional resistance can be pervasive, as one warden described: “Programming is not appreciated inside [by staff] (…) and lots of the programming we put in place is no longer available [since the pandemic].”

Because of the challenge of bringing art supplies and materials into prisons, as well as lack of funding, some organizations resort to alternative ways to introduce incarcerated people to the arts. For instance, Callan Steinmann, head of education and curator of academic and public programs at the Georgia Museum of Art at University of Georgia, brought printed copies of artwork inside, asking incarcerated women at Whitworth Women’s Facility in Hartwell, Georgia, to reflect upon and write about them. The Insight Garden Program introduced garden design as an artform, working with incarcerated learners through in-person and correspondence courses that produced sketches of ideal garden designs and identification of plants through a series of botanical drawings.[10]

We did hear of several model arts teaching programs. The first is JAC’s correspondence course, “CorrespondARTS.” The course was first launched in a Maryland women’s prison at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, thanks to a small group of teaching artists and the support of a sympathetic warden, as hundreds of in-person arts programs happening in prisons around the country came to a sudden halt. The artists created multidisciplinary activity packets, which they would personally deliver to the facility. Every two weeks, the artists would return to deliver new packets and pick up students’ work. Throughout the COVID-19 crisis, JAC advised artists and organizations developing similar programs around the country, some of which continue to this day. The second is the Alabama Prison Arts + Education Project at Auburn University, which describes its mission this way: “Alabama Prison Arts + Education Project was founded with the knowledge that creativity is an essential trait of humanity. In correctional facilities throughout the state of Alabama, Alabama Prison Arts + Education Project works to create spaces wherein humans can practice meaningful engagement with the arts and develop their own artistic voices.”[11] Alabama Prison Arts + Education Project works with faculty members and community artists to offer foundational classes for basic skills, artist in residence programs, and instructional drawing packets.

Finally, we heard about incarcerated artists themselves working to build creative spaces and programs at their facilities. In some cases, these programs—often just consisting of a small “art room” inside the facility—rely on external volunteers for supplies and administrative sponsorship but are almost entirely run by incarcerated artists. The Nash Art Guild is a primary example. The program, operating since 2014 at North Carolina’s Nash Correctional Institution, offers beginner to advanced art classes and even organizes outside exhibits. The Guild is managed and run by incarcerated artists.

Bringing materials in

In the vast majority of cases, especially when arts programs are not available, incarcerated artists face multiple barriers to obtain the materials they need to practice their craft. Policies regarding what materials are allowed and how to obtain them vary not just across DOCs, but by facility as well. One interviewee told us, “What can be brought in changes constantly. You dream big, you get told yes or no, but that changes semester by semester, or even during a course.” Most facilities have very limited lists of hobbycraft materials that people can purchase from external vendors using their commissary accounts. Approved “hobbycraft lists” vary by facility, but often do not include crucial supplies such as fixative spray and, sometimes, not even the bare minimum. Richard,[12] an artist serving time in North Carolina, said that in one of the medium-security facilities where he was detained paper larger than A4 size was considered contraband and so were mechanical pencils, eraser sticks, and any kind of paint. Wendy Jason, JAC’s founder and former executive director, told us about one artist she has worked with for years who isn’t allowed to have any paper at all, so he purchases white handkerchiefs and uses them as canvas. The same artist makes his own paint by emptying out the ink from a ballpoint pen.

“Mutant Dog,” by Cuong “Mike” Tran[13]

Regardless of policies in place, the collaboration or hostility of staff members can still make, or break, an artist’s ability to obtain even formally allowed material. Trey Livingston, for instance, said that he learned quite quickly that good relationships with the mailroom staff were key to getting his art supplies in a timely fashion—and to ensuring that items weren’t lost or rejected. To cultivate those relationships, he used to regularly gift the staff paintings. “A lot of staff expect things for free,” he explained. “You have no choice, they have all the power and can make your life harder.”

Even when material is available, and correctional staff cooperative, most incarcerated artists cannot afford to buy all the supplies they need. Without consistent support from their families, most cannot buy any at all and instead resort to contraband or low-cost alternatives, such as creating watercolor paints with coffee or tea or papier-mâché out of toilet paper and soap.[14]

Censorship and staff hostility

A few incarcerated artists mentioned receiving support from staff members, and we heard directly from several DOC officials who understood the positive impacts of the arts and encouraged the practice in their facilities. Most interviewees, however, reported experiencing serious repercussions, including censorship, disciplinary actions, and even abuse from staff, just for practicing art while incarcerated.

Censorship, Matt explained, would target first and foremost those suspected of relaying political or activist messages through their art, but it could go beyond that to rein in any creative expression that did not conform to institutional norms. Towards the end of his incarceration, Matt was tasked with painting a mural along one of the facility’s corridors. “Staff hated it,” he said, “It was too imaginative.” Two weeks before he was transferred, they started painting over it. As another participant put it when describing his experience doing art inside, “[in prison] there is always someone watching and censoring what you are working on.”

Many of the artists we interviewed also reported becoming the target of staff hostility or abuse due to their creative practice. Navigating relationships with staff, making sure they remain supportive or at least indifferent to their activities, is a crucial part of being an incarcerated artist, several participants explained to us. While some had been lucky enough to encounter correctional officers who genuinely appreciated their craft and what they were trying to accomplish, most reported having to do “commissions” for officers in order to stay on their good side. When relationships with staff were not as positive, artists reported being denied access to art spaces or the mail room, or having their cells subjected to particularly aggressive searches, during which their material could be damaged, trashed, or confiscated as contraband.

Lack of space for artmaking and storage

One common complaint voiced by the artists we interviewed was the almost complete lack of space both for practicing art and for storing their work. Only a few facilities had dedicated art rooms, and even when those were present they had long waiting lists, and were only accessible for limited times.[15] Kyes Stevens, executive director of the Alabama Prison Arts + Education Project, said artists in the facility where her program operated had a hard time finding any flat surface large enough for painting. Some worked on their bunks, while others waited until the middle of the night in order to use the dorm floor as their surface.

Limited, or non-existent, storage space was mentioned by all the artists as one of the main challenges they were facing inside. Malcolm, an artist currently incarcerated in the California prison system, for instance, reported only having six cubic feet of cupboard space to be used as storage in his current facility—not nearly enough to store his supplies, let alone his works. After he became an art instructor in his federal facility, Greg Bolden had access to a larger cabinet and additional locker. Transfer to a new facility, however, resulted in losing those hard-won privileges, together with much of the works and material he had accumulated.

Like with obtaining supplies and navigating censorship, figuring out ways of storing artworks and materials takes resourcefulness, persistence, and out of the box thinking on the part of incarcerated artists. While some of our interviewees were more successful than others in devising solutions to space problems, the bottom line was the same for everyone: art cannot be stored and preserved inside prisons; safely getting artworks outside, and in the hands of trusted partners, is a priority for all incarcerated artists.

Circulating, exhibiting, and preserving art on the outside

The everyday challenges experienced by incarcerated artists—including censorship, searches, and the lack of storage and materials for preservation—means that getting artworks out of the prison is a priority for incarcerated artists, as well as for the organizations working with them, from higher education in prison programs to cultural memory institutions and grassroots organizations. In this section, we explore how works by incarcerated artists are brought outside the prison and how partner organizations collect them and share them with the public through a variety of venues, including exhibitions, anthologies, social media, magazines, and public programming. We will look at the barriers faced at each of these critical junctures, and how organizations across the country are addressing them, despite often extremely limited resources.

Sending art out

Due to the lack of access to storage and preservation materials inside the prison, most artists regularly mail their works to families and partner organizations on the outside. Rules and regulations about what can be sent out, and how, differ in every facility, with some allowing higher education in prison programs and art instructors to bring students’ work outside with them. Shipping supplies, moreover, can be hard to find, and their cost is often prohibitive for incarcerated artists. Once again, our participants explained to us, keeping good relationships with mailroom staff is key to avoiding artworks being damaged or lost on their way out.

Some of the artists we interviewed would send all their works to their families. Both Matt, who served time in Pennsylvania, and Anthony,[17] an artist currently incarcerated in Maryland, for instance, mailed their artworks to their mothers, relying on them for storage and preservation. During his incarceration, Matt used to send his mother five to 10 pieces at a time, which she sprayed with fixatives, scanned in high resolution, and stored.

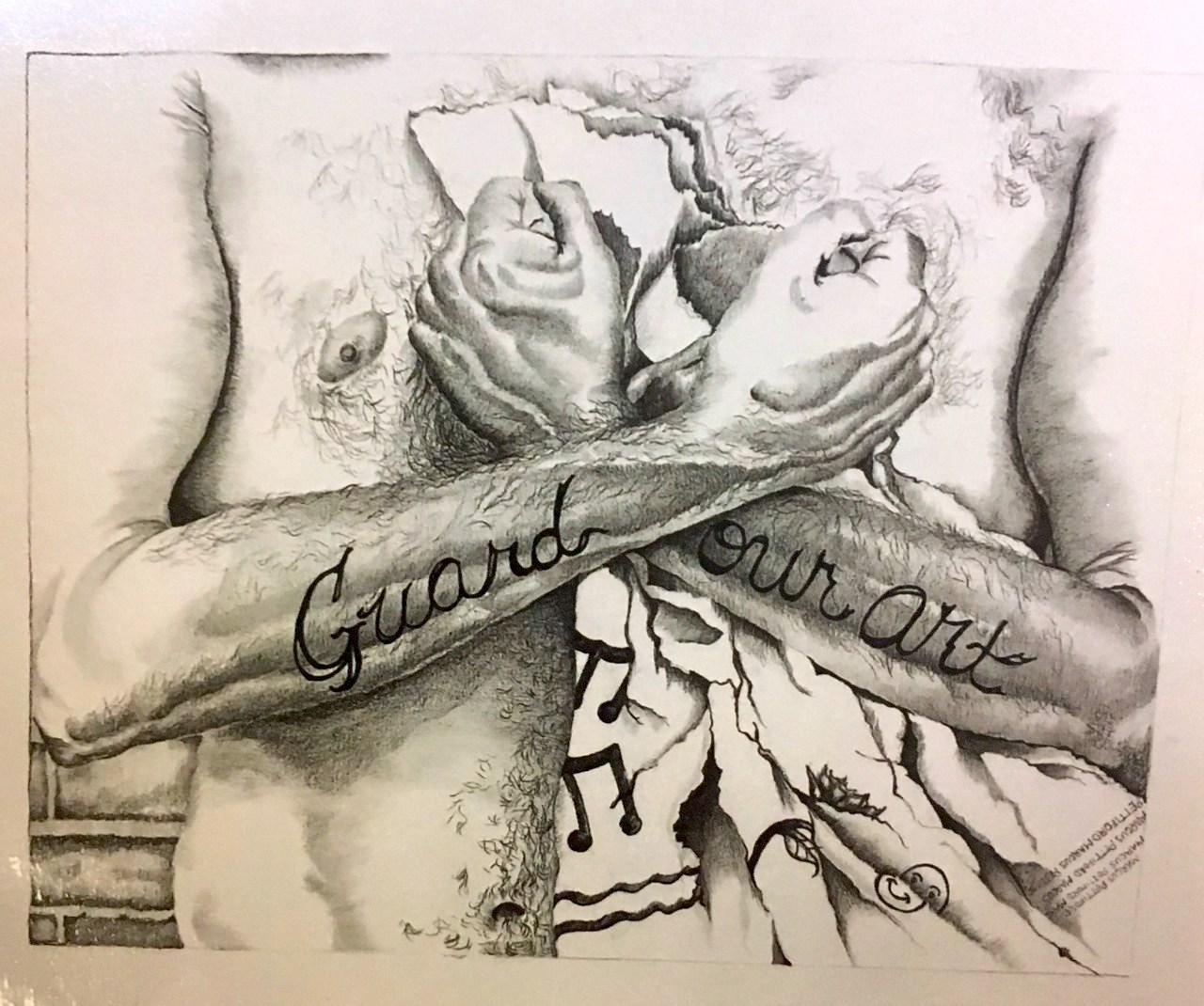

“Guard Our Art,” by Kid Wif Da Crayons[16]

Other artists entrusted their works to outside organizations, such as higher education in prison programs or grassroots community groups. For example, over 120 incarcerated people have participated in Art from the Inside MN, an organization first established after the COVID-19 pandemic that works with artists in five state prisons across Minnesota. Antonio and Jessica Espinosa, founders of Art from the Inside MN, explained that thanks to relationships they were able to build with wardens, they were allowed to bring participants’ artwork out. Higher education in prison faculty we interviewed reported similar agreements, both formal and informal, with the facilities in which they operate.

Other organizations, like the Justice Arts Coalition, provided safe storage, developed online portfolios, and promoted the work of incarcerated artists across the nation who regularly mailed their works to them. Most artists, Wendy Jason, JAC’s founder and former executive director explained, heard about the organization through word of mouth, either via fellow artists in their facilities or through their loved ones. JAC’s information was also sometimes included in resource guides and magazines for incarcerated people. JAC’s growing renown in the art community came with its own problems for a small grassroots organization: after a couple of years of amassing artwork, JAC had no choice but to request that artists limit the number of works they sent per year.

Making art public

All of the artists we interviewed deeply cared about sharing their art with a broader public outside the prison, both to gain recognition for their work and to educate the public about life conditions they and their peers faced inside. Those, like Matt and Anthony, who sent their artwork to families for collection and storage, usually relied on them also for public dissemination. Anthony’s mother, for instance, posts his work on social media accounts online and works with him to call galleries interested in exhibiting his art. Artists like Matt and Anthony, who are trying to navigate the art world alone or with help solely from families, report having both successes (e.g., getting published in a magazine, participating in outside exhibits) as well as disappointing experiences, including organizations not acknowledging their contributions or even failing to return their works.

Avoiding the latter, and protecting the interests and safety of incarcerated artists while making their work accessible to a larger public, is central to the mission of organizations such as Art from the Inside MN and the Justice Arts Coalition. Malcolm,[18] an artist currently serving time in California, recounted that after cold-calling galleries and art magazines for years without much success, it was only after a friend introduced him to JAC that he was able to exhibit his work outside the prison. JAC used multiple strategies to amplify the work of artists like Malcolm, from facilitating collaborations with other organizations and news outlets, such as the Marshall Project and Prison Journalism Project, to organizing original exhibits like, most recently, the “Prison Re-imagined: Presidential Portraits Project” which featured presidential portraits next to each president’s record on incarceration.[19] “For that exhibit,” Wendy Jason noted, “we were just the boots on the ground. We were doing the labor but incarcerated artists were leading and doing all the creative work for the exhibition.”[20]

Higher education in prison programs have also been active in organizing and promoting exhibits featuring incarcerated artists, often in collaboration with museums and other memory institutions. Starting in 2022, for instance, the Alabama Prison Arts + Education Project has been organizing “Changing the Course,” an annual exhibit of art by incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people.[21] The exhibit, hosted by the Alabama Department of Archives and History, has even been formally endorsed by the state’s Bureau of Pardons and Paroles and department of corrections. In 2023, faculty and students at the University of Georgia worked with the Georgia Museum of Art to create “Art is a form of freedom,” an exhibit featuring poetry and prose written by incarcerated women in dialogue with the museum’s collection.[22]

Beyond museum exhibits, artwork by incarcerated individuals is made public through journals and zines, anthologies and book chapters, websites and greeting cards, just to name a few of the examples we have come across. ABO Comix, whose main mission is uplifting the voices and experiences of queer prisoners, for instance, organizes a wealth of public programming, including workshops and open mic nights with formerly incarcerated artists, and has published over 50 books and zines with art by incarcerated artists. For over a decade, people at Trinidad Correctional Facility in Colorado participated in the local art-car parade by designing and decorating a vehicle donated by the community to the prison.[23]

Ethical considerations around collecting and showing work

Whatever the venue they were using to share works by incarcerated artists, all instructors and curators we interviewed spoke of the importance of protecting their privacy and safety, as well as about some of the recurring challenges they faced. First, everybody stressed the importance of having a clear process to gain consent from incarcerated artists before their work is shared with the public. That process, they explained, needs to include a transparent conversation about how the artist is going to be acknowledged. Many incarcerated artists are eager for the public to know them and would like to have their full names acknowledged. That, however, is sometimes forbidden by DOC regulations. Even when full acknowledgment is an option, it is important to caution the artist concerning the possible risks of doing so. As Antonio and Jessica Espinosa from Art from the Inside MN told us, public reactions can be unpredictable, and their organization always works to engage victims as well before an exhibit to ensure they are not re-traumatized. Kyes Stevens, from the Alabama Prison Arts + Education Project, told us that while to her knowledge the Alabama DOC never retaliated against artists who exposed their work at “Changing the Course,” even when the artwork was very critical of the prison system, there has been a case in which the content of a published essay was used against the writer in their parole hearing. She always makes sure to bring that up in conversation with artists about privacy.

“Please Wake Me,” by Mark Loughney[24]

In addition to protecting their privacy, ensuring that incarcerated artists are aware of, and given agency around, how their work is being used, updating them every step along the way, and maximizing the feedback they can receive from the public is another priority. In a recent exhibit, for instance, Art from Inside MN had a documentarist recording visitors’ reactions to the work, to be able to share the responses with the artists. Similarly, the Georgia Museum of Arts created a database to collect public reactions to the “Art is a Form of Freedom” exhibit for the artists at Whitworth Women’s Facility.

Despite the best efforts of organizations to gain consent and protect the safety and privacy of the incarcerated artists they support, many challenges remain. As one interviewee from the Alabama Prison Arts + Education Project summed up, “In all realms of higher ed and art in prison, there’s a big problem with work being used without permission. They obtain permission off the bat but would need to go back for permission if there was to be any new use of art. This is a barrier to public access to the work, especially because they can’t track down all past participants. They don’t want to push people back into trauma by making them revisit time in prison, even if it’s just about the creative work they produced while there. We’re very cautious around anything that could be exploitative.”

Selling artworks

While the organizations we talked to, including Art from the Inside MN and JAC, said that selling artwork wasn’t part of their main mission, they also recognized that it was a priority for many artists they worked with and that they regularly received inquiries by artists about sales opportunities. For many artists, especially if they were not receiving regular support from their families, selling their work was the only way to support themselves while inside, as well as to cover at least some of the costs of practicing their craft, from buying art materials to shipping.

Despite this need, there is currently no structure in place to support incarcerated artists in bringing their work to the market. A few artists we talked to were trying to work with friends and family to set up digital shops on platforms such as Etsy or Instagram, usually without much success. Over the last years of her tenure as executive director, Wendy Jason told us, JAC tried to pivot to provide more marketing and sales opportunities for incarcerated artists, but logistical, legal, and administrative challenges were daunting, especially for a small organization.

Preservation and archiving

Beyond being able to share their work with a wider public, the main reason incarcerated artists send their work outside is to ensure it will be preserved over time. As we described above, prison presents almost insurmountable challenges to preservation, from the lack of access to supplies such as fixative spray to the chronic absence of space for storage. Even in the rare instances when incarcerated artists manage to gain access to both, they are still subjected to the risks of suddenly losing years’ worth of work due to searches, transfers, or disciplinary actions.

While not experiencing the same constraints, families and partner organizations on the outside still face considerable barriers to archiving and preserving the artwork they receive from incarcerated artists. In this section, we document some of those challenges and needs, as well as best practices and promising strategies already emerging in the field.

Archiving prison art

A few artists we interviewed relied entirely on families to store and preserve their works. While for some that resulted in frequent damage and loss, as their families did not have the resources and/or the knowledge necessary to preserve artwork, in other cases people learned how to safely handle works they received from inside. Often, that involved a trial-and-error process. Greg Bolden told us that he and his wife had developed a fairly safe system while he was incarcerated. He learned that it was best to send out his work on unstretched canvases, and she figured out better techniques to stretch and seal paintings before storing them in her basement. Before sealing each painting, she would also take pictures and save them in an online folder.

Bolden’s wife was more of an exception though. Not only most family members but also several of the organizations we interviewed reported struggling to keep up with the work of archiving and preserving artwork from inside.

Lack of storage space, and of staff dedicated to collecting and archiving incoming artworks, were some of the primary concerns our interviewees voiced. ABO Comix, for instance, receives 100 to 200 letters and drawings every month from incarcerated artists and writers. They preserve all physical copies, and at the time of the interview they reported having close to 7500 pieces in filing cabinets and art storage boxes, located in a building that they described as “old, leaky, and not safe for preserving artworks.” Their hope is to eventually collaborate with an archive or other memory institution to find a more suitable space for their growing collection. Similarly, Art from the Inside MN representatives told us that the amount of work, and special expertise, required to safely store artwork initially took them by surprise: “We thought this was going to be easy, you just take the art and sell it.” While that is still largely their model, with most artwork being sold or sent to families after each exhibit, they also quickly figured out they were going to be responsible for preserving all the art that could not be sent out. Art from the Inside MN had one of the most thorough preservation processes we have come across in our research, with each of between 50-80 pieces of art bubble-wrapped, put in a plastic bin, and placed in a basement with dehumidifiers.

Other participants, including staff members with the Insight Garden Program and the Alabama Prison Arts + Education Project, said their organizations just didn’t have access to enough space for storing large numbers of artworks, and their facilities were not equipped with essential features such as temperature control. Mary Gould—who as the executive director of the Sunshine Lady Foundation works with several higher education in prison programs—said that as far as she could tell, even the smaller organizations we interacted with were doing more than most to preserve the works they received from inside: “many programs, she said, have just some boxes on a shelf in their office containing art from inside.”

Promises and challenges of digitization

In no small part due to the limitations and risks of physical storage, all the instructors and curators we interviewed were making efforts to digitally catalog and archive the artworks they received from incarcerated artists. That allowed them not only to safely preserve the artworks, but also to make them more widely accessible to community members, advocates, researchers, and the artists themselves. A few organizations, like Art from the Inside MN and JAC, have developed effective ways to digitally archive the works they receive through dedicated art storage databases.

Most people we spoke to, however, mentioned a lack of funding and dedicated staff as primary challenges to creating comprehensive and fully accessible digital archives. Becca Greenstein, board member at Chicago Books to Women in Prison, for instance, told us that given the organization’s current capacity, time—to label all material, develop the metadata, manage the database—was the main constraint they were facing. The two-person staff at ABO does its best to scan every single drawing they receive, save them in a cloud storage drive, and add information about each piece to a spreadsheet, but they feel they will be unable to keep up if the influx of art they receive keeps growing. Kyes Stevens said that the Alabama Prison Arts + Education Project has been looking for funding to develop and improve their existing archive because properly archiving art is expensive: “You need a high-resolution scanner, ideally a designated room with appropriate lighting to process and photograph the works, and lots of cloud space.”

While everybody agreed that more funding was urgently needed to increase the field’s capacity to preserve art from inside, our interviewees also said that lack of clear guidelines for best practices was holding their organizations back. What metadata should be captured, and how, was a recurring question among many curators, and so were the pros and cons of different digital preservation software. Finally, many wished there were clear guidelines for how to reach out to obtain permission from incarcerated artists and to balance dissemination with the need to protect their privacy and safety.

Conclusion

The arts can be a lifeline for those in prison, helping them to redefine themselves, understand their world, and give meaning and purpose to their lives, while also building and sustaining connections with people outside, combatting their sense of isolation. Incarcerated people are creating an enormous amount of art; and, especially for visual artists, much of it is produced under challenging constraints. Incarcerated artists face a multitude of barriers, from availability of workspace to a lack of art instruction, difficulty obtaining materials, challenges in storing their work, censorship, and difficulty in sending their work outside, whether to family members or to one of the grassroots organizations that help foster the arts in prison.

These grassroots organizations have become an essential partner for many of the incarcerated artists they serve, bringing them arts programming inside and an array of opportunities beyond the prison walls to showcase, and in some cases, sell their work. In addition to aiding the artists themselves, the public benefits greatly from these organizations efforts to preserve and make accessible creative work, and to build windows into the often-hidden realities of American prisons. But these organizations form a fragile ecosystem with many challenges of their own. Most are run on a shoestring, dependent on volunteer effort and donations, so bandwidth is a constant problem. They struggle to navigate the often-changing rules of DOCs, develop ethical consent practices, find storage solutions for the growing body of work they are entrusted with, and devise archiving and preservation solutions, both physical and digital, for the collections they are stewarding. While we encountered some promising partnerships, between grassroots organizations and DOCs, museums, and colleges and universities, many of these organizations face these challenges on their own. The landscape is fragmented and fragile and can’t scale in a way that helps to overcome challenges and foster opportunities.

Our findings suggest several directions for further research.

- What is the broader landscape of arts instruction in prisons? How many courses are offered and in which fields? Which organizations are offering what types of courses?

- What is the long-term effect of exposure to the arts in prison? How does exposure affect current and formerly incarcerated writers and artists? How does it affect DOCs and the environment inside prison facilities?

- The grassroots organizations that foster the arts in prison and collect and care for the artistic output of incarcerated creators need advice and training about best practices for archiving and preservation as well as opportunities for knowledge sharing. There are emerging communities of practice in this space—such as The Archives of Prison Witness working group, organized by the American Prison Writing Archive—but most organizations still operate in isolation from each other. How do we build on these efforts by providing opportunities for sharing learnings, and producing the toolkits and training needed by grassroot organizations and family members working in this space?

- Partnerships between different types of organizations—such as prison education programs, cultural memory institutions, and advocacy organizations—could play an important role in helping to develop access and preservation solutions for the creative work produced in prisons. This is true for both physical and digital archiving efforts. Traditional memory organizations such as libraries and museums have an important role to play, as do organizations that provide digitization, hosting, and preservation services. How can we help to build this shared network so that there is a growing record of the artistic lives of incarcerated people for this, and future, generations?

Acknowledgements

This report is made possible with funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, whom we thank for their support. Most importantly, a big thank you to all the artists, curators, and educators who spoke with us—your voices and experience make this work possible. Special thanks to our collaborator Wendy Jason for sharing her wisdom and contacts in the field. Thanks also to the project’s advisory board, whose guidance was integral to the project: Treacy Ziegler, Doran Larson, Jodi Lincoln, Rahsaan Thomas, Steven Fullwood, and Hilary Bindal. Finally, thank you to Kurtis Tanaka and Ess Pokornowski, who helped along the way.

Endnotes

- For a review of the “collateral consequences” of mass incarceration in the United States see: David S. Kirk and Sarah Wakefield, “Collateral Consequences of Punishment: A Critical Review and Path Forward,” Annual Review of Criminology 1 (January 2018), https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-criminol-032317-092045. ↑

- See Emily Widra, “Ten Statistics About the Scale and Impact of Mass Incarceration in the US,” Prison Policy Initiative, October 24, 2023. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2023/10/24/ten-statistics/. ↑

- See Nicole Fleetwood, Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2020). ↑

- See, for instance, the American Prison Writing Archive at Johns Hopkins University, the largest collection of letters written by incarcerated people in the United States: https://prisonwitness.org/. ↑

- Justice Arts Coalition, https://thejusticeartscoalition.org/. ↑

- To learn more about Robert Odom’s art, visit his Instagram: @robertsprisonblues, https://www.instagram.com/robertsprisonblues/. ↑

- To learn more about Greg Bolden’s art, see Bold-N-Art LLC, https://bold-n-art.square.site/ ↑

- Name was changed to protect the privacy and safety of the artist. ↑

- To learn more about William “Trey” Livingston’s art, visit the Sunset Club Records website, https://sunsetclubrecords.com/william-b-livingston-art. ↑

- The Insight Garden Program is now known as Land Together. For more information about the program, see the Land Together website, https://www.landtogether.org/faq. ↑

- Alabama Prison Arts + Ed Project, Auburn University, https://apaep.auburn.edu/. ↑

- Name was changed to protect the privacy and safety of the artist. ↑

- To learn more about Cuong “Mike” Tran’s art, visit his Instagram: @crucible118, https://www.instagram.com/crucible118/. ↑

- In the US, most incarcerated people are assigned jobs by their facilities but are only paid cents an hour, or nothing at all, for their work. As a result, they have to rely on financial support from friends and families from the outside to cover even basic needs such as food and hygiene products from prison commissary stores. See American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and Global Human Rights Clinic of the University of Chicago Law, “Captive Labor: Exploitation of Incarcerated Workers,” ACLU, June 15, 2022, https://www.aclu.org/publications/captive-labor-exploitation-incarcerated-workers. ↑

- On the lack of educational spaces inside prison see: Tammy Ortiz, Sindy Lopez, and Ess Pokornowski, “Uneven Terrain: Learning Spaces in Higher Education in Prison,” Ithaka S+R, October 7, 2024, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.321385. ↑

- To learn more about this artist’s work, visit his Instagram: @kidwifdacrayons, https://www.instagram.com/kidwifdacrayons/. ↑

- Name was changed to protect the privacy and safety of the artist. ↑

- Name was changed to protect the privacy and safety of the artist. ↑

- “Prison Reimagined: Presidential Portrait Project,” President Lincoln’s Cottage, https://www.lincolncottage.org/event/prison-reimagined-presidential-portrait-project/. ↑

- The exhibit concept for “Prison Reimagined” was developed by Caddell Kivett, an incarcerated writer at Nash Correctional Facility (NC). Kivett developed descriptions and calls for submissions and put together a team of artists and writers at Nash to receive submissions and select pieces for the exhibit. JAC handled logistics in partnership with exhibition host, President Lincoln’s Cottage. ↑

- “ADVISORY: Annual Changing the Course Art Exhibition Event Happening Tuesday in Montgomery,” Alabama Bureau of Pardons, and Paroles, March 12, 2024, https://paroles.alabama.gov/2024/03/12/advisory-third-annual-changing-the-course-art-exhibition-event-happening-tuesday-in-montgomery/. ↑

- “Art Is a Form of Freedom,” Georgia Museum of Art,https://georgiamuseum.org/exhibit/art-is-a-form-of-freedom-whitworth-women-select-works-from-the-collection/ ↑

- The Trinidad Art Car parade was discontinued during the COVID-19 pandemic and could not resume due to lack of funding. ↑

- To learn more about Mark Loughney’s art, visit his Instagram: @loughneyart, https://www.instagram.com/loughneyart/. ↑