Supporting First-Generation Students in a Time of Crisis

Lessons from the Kessler Scholars Program Response to COVID-19

-

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The evolution of the Kessler Scholars Collaborative

- The Kessler Scholars Program model

- COVID-19 Pandemic experiences of the 2020 cohort of Kessler Scholars

- Adapting program supports for students in a time of crisis

- Tracking success outcomes of the 2020 cohort

- Promising practices for supporting first-generation students through crisis

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgements

- Endnotes

- Introduction

- The evolution of the Kessler Scholars Collaborative

- The Kessler Scholars Program model

- COVID-19 Pandemic experiences of the 2020 cohort of Kessler Scholars

- Adapting program supports for students in a time of crisis

- Tracking success outcomes of the 2020 cohort

- Promising practices for supporting first-generation students through crisis

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgements

- Endnotes

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic had a profound effect on higher education and students. In the spring of 2020, amidst great uncertainty, many colleges and universities closed campuses and abruptly shifted from in-person to virtual instruction to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 virus. Several studies point to negative impacts of these disruptions on students, including reduced academic performance and learning loss,[1] decreased opportunities to participate in high-impact practices,[2] greater financial hardships, and basic needs insecurity, and greater struggles with mental health for students.[3] Institutions were also impacted—enrollment, persistence, and completion rates fell, and many colleges and universities experienced revenue losses and staff layoffs.[4] These challenges exacerbated existing gaps in college access and success for first-generation and low-income students.[5]

Survey data suggests that first-generation students were more likely than their continuing-generation peers to experience mental health concerns, food and housing insecurity, and financial difficulties due to lost wages from employment or family members during the pandemic.[6] They also experienced greater challenges in adapting to remote instruction due to a lack of adequate technology and dedicated study spaces, and were more likely to take a leave of absence and withdraw from college.[7] Furthermore, compared to non-Pell students, Pell Grant recipients were more likely to lose a job and experience earnings losses due to the pandemic.[8]

The Kessler Scholars Collaborative was formally established in early 2020 with a vision to promote access and success for first-generation, low-income college students through comprehensive cohort-based programming, individualized proactive support, and financial resources. The Collaborative’s launch just preceded the onset of the pandemic, as institutions were navigating the sudden shift to remote operations by redesigning courses and adapting support services to meet emerging needs. This created a unique challenge for the Collaborative as it began its operations and required rapid adaptation of the program’s high-touch in-person model to provide virtual support to Kessler Scholars during a period of widespread disruption. As the Collaborative welcomed its first cohort of students across six institutions in the fall of 2020, its leadership partnered with key stakeholders from all partner campuses to reimagine programming to reinforce a sense of belonging to the program and institution, encourage broad academic and co-curricular exploration, and support students throughout their college experience.[9]

This brief offers insights into the pandemic-era college experiences of the Collaborative’s inaugural cohort—the 2020 cohort—and examines how comprehensive support provided by the Kessler Scholars Program promoted belonging, persistence, and completion for first-generation students during this period of disruption. Now that the 2020 cohort has reached the four-year graduation milestone and outcomes data are available, we can examine their full college journey and assess the long-term effectiveness of the program adaptations implemented during the pandemic. These insights are particularly valuable as higher education continues to navigate ongoing disruptions due to factors such as enrollment declines, institutional closures, the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence, and shifts in government policies and regulatory requirements, while institutions seek evidence-based strategies for supporting vulnerable student populations during both crisis and stable periods.

Three key research questions guided our analysis:

- What were the backgrounds and experiences of the 2020 cohort of Kessler Scholars served during the 2020-21 academic year, and what challenges did they face during the pandemic and across their undergraduate journey?

- What support did the Kessler Scholars Program offer to participating scholars during the pandemic, and how did this support influence their college experiences and outcomes?

- How can the lessons learned from the pandemic improve program and institution-wide support for first-generation and low-income students?

To answer these research questions, we draw on mixed-methods data collected as part of the multi-year external evaluation of the Kessler Scholars Program, relevant program documentation, and assessments conducted by the Kessler Scholars Collaborative.[10] This data includes:

- Surveys of Kessler Scholars, which were conducted in Fall 2020, Spring 2021, and Spring 2024, and include self-reported demographics, psychosocial outcomes such as sense of belonging, as well as institutional experiences for the 2020 cohort;[11]

- Student-level administrative data submitted by institutional research offices at participating institutions, which include demographics and enrollment status for Kessler Scholars and other first-generation students at partner institutions;

- Student rosters shared by campus program teams, tracking students’ enrollment status and program participation throughout the year; and

- A listening session led by the Collaborative leadership in partnership with the evaluation team in Spring 2025, which held space for the 2020 cohort (now alumni) to reflect on their college experiences during and after the COVID-19 pandemic and share feedback on program support structures for Kessler Scholars.

The remainder of this brief describes the evolution of the Kessler Scholars Collaborative and the backgrounds and pandemic-era experiences of its inaugural cohort. It draws on student and staff accounts, as well as relevant program documentation, to describe program adaptations that enabled the success outcomes of Kessler Scholars during the pandemic and highlighted promising strategies for providing comprehensive support to first-generation, limited-income students.

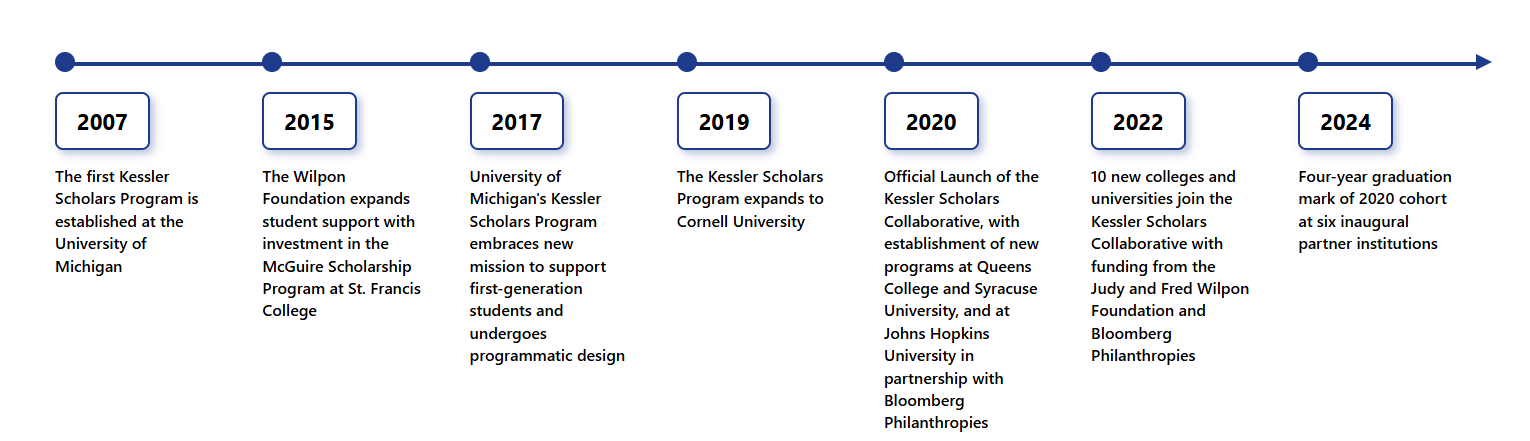

The evolution of the Kessler Scholars Collaborative

The Kessler Scholars Program was first established in 2008 as an undergraduate scholarship at the University of Michigan with generous funding from the Judy and Fred Wilpon Family Foundation and central coordination provided by the University of Michigan’s College of Literature, Science, and the Arts (LSA). The program was redesigned to focus on first-generation, low-income students in 2017. The Wilpon Family Foundation expanded student support to the McGuire Scholars at St. Francis College in 2015 and then added a Kessler Scholars Program at Cornell University in 2019. Additionally, three new Kessler Scholars programs were launched in the fall of 2020 at Johns Hopkins University, Queens College, and Syracuse University as part of the formal establishment of the Kessler Scholars Collaborative, a nationwide network that supports the students and staff who are part of the Kessler Scholars Program. Together, the Collaborative served more than 300 students during the 2020-21 academic year at these six inaugural institutions. At the same time, the Collaborative began early efforts to define its collective impact goals and support program development and shared learning across partner institutions, and initiated a systematic external evaluation to track students’ experiences and outcomes.[12]

Together, the Collaborative served more than 300 students during the 2020-21 academic year at these six inaugural institutions.

Figure 1: Key milestones in the Kessler Scholars Program evolution

In 2022, 10 additional institutions joined the Collaborative as a partner project of the American Talent Initiative (ATI), a coalition of public and private institutions with high graduation rates that are committed to expanding college enrollment and success for low- and moderate-income college students.[13] With generous support from the Judy and Fred Wilpon Family Foundation and Bloomberg Philanthropies, these ATI member institutions welcomed students to new Kessler Scholars Programs in fall 2023: Bates College; Brown University; Centre College; Saint Mary’s College; The Ohio State University; University of California, Riverside; University of Dayton; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; University of Pittsburgh; and Washington University in St. Louis. During this expansion, Ithaka S+R also began serving as the external evaluation partner for the Collaborative, leading a mixed-methods, formative assessment intended to support implementation and maximize impact across the network.[14] Today, the Collaborative works to support first-generation student success by guiding program development, building the capacity of campus-based leaders and practitioners to effectively support students, integrating and sharing evidence-based best practices, and fostering meaningful connections among scholars, alumni, and practitioners across institutional boundaries. In spring 2024, the Collaborative celebrated a significant milestone in its journey—the graduation of the fall 2020 entering cohort, the first full cohort enrolled across all six inaugural institutions after the Collaborative began operations.[15]

The Kessler Scholars Program model

Completing college offers substantial benefits to both individuals and society, including increased individual earnings, improved health, greater civic engagement, and a stronger economy.[16] However, first-generation college students, who comprise over half of all undergraduates, face significant barriers to degree attainment.[17] Only 24 percent earn a bachelor’s degree within six years compared to almost 60 percent of students whose parents hold degrees.[18] These students often struggle with lower levels of academic preparation during high school, less financial support, greater responsibilities outside of school, and challenges with campus belonging that contribute to them being 71 percent more likely to leave college in their first year than their continuing-generation peers.[19] A growing body of rigorous evidence suggests that comprehensive student success programs, which combine several multi-year interventions—such as academic support, advising, financial aid, basic needs support, and learning communities—to address the multiple potential barriers that students might face, are most effective for increasing college access and success for students from historically underrepresented backgrounds.[20]

First-generation college students, who comprise over half of all undergraduates, face significant barriers to degree attainment.

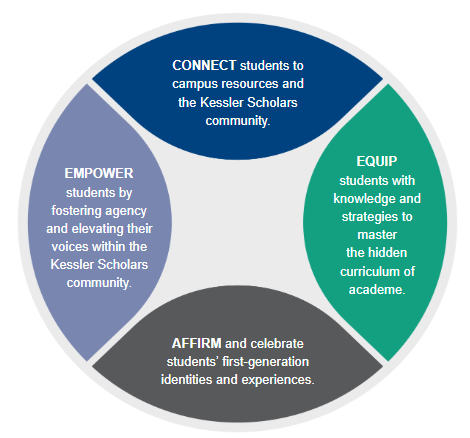

The Kessler Scholars Program is one such program designed to provide holistic support for students from lower-income households who are the first in their families to pursue a four-year college degree. Through a combination of financial resources, cohort-based engagement, and individualized guidance, the Kessler Scholars Program provides first-generation, limited-income students with the knowledge, skills, and experiences they need to succeed and flourish in college and beyond. In addition to financial support, all Kessler Scholars benefit from individualized academic, personal, and social support by a cohort of fellow first-generation students and professional staff, designed to provide a meaningful and transformative experience for first-generation students and ensure their success. Core program components include one-on-one meetings with a Kessler Scholars staff member, general and cohort-based workshops and activities, peer mentorship, student leadership opportunities, and community service opportunities. The program aims to close equity gaps in persistence and completion between first-generation students and their continuing-generation peers; foster a sense of belonging and feelings of mattering to the program and broader campus communities; and create a vibrant and engaged community of scholars and alumni across campus partners.

Figure 2: High-level program goals

COVID-19 Pandemic experiences of the 2020 cohort of Kessler Scholars

In the fall of 2020, the Collaborative enrolled its first cohort of Kessler Scholars across its six inaugural partner institutions. The 2020 cohort included approximately 136 students across six partner institutions: the University of Michigan (40), Cornell University (20), Johns Hopkins University (16), Queens College (16), St. Francis College (26), and Syracuse University (18). As shown in Table 1, around 28 percent of the cohort self-reported as Hispanic or Latino, 20 percent as Black, and 19 percent as white; six in 10 students identified as female, and nine in 10 students identified as the first in their families to attend college.[21]

Table 1: Selected characteristics of Kessler Scholars, Fall 2020 Cohort

| Characteristic (%) | 2020 Cohort | Sample Size |

| First-Generation | ||

| Yes | 91% | 121 |

| No | 8% | 11 |

| Total Sample Size | 133 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 28% | 37 |

| Black/African/African American | 20% | 26 |

| White/Caucasian/European American | 19% | 25 |

| Asian/Asian American | 16% | 8 |

| Multi-racial/ethnic | 11% | 15 |

| Total Sample Size | 133 | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 63% | 76 |

| Other | 21% | 25 |

| Male | 17% | 20 |

| Total Sample Size | 121 |

Data Sources: Race/Ethnicity and First-Generation Status – Fall 2020 Kessler Scholars Survey. Gender – 2024 Institutional Data Submissions. Sample sizes vary between data sources due to survey non-response or missing data. The Fall 2020 Kessler Scholars Survey includes all inaugural institutions except Cornell University. Missing data for Cornell is imputed using the 2024 Institutional Data Submission. The 2024 Institutional Data Submission includes all inaugural institutions except Johns Hopkins.

The 2020 cohort of Kessler Scholars experienced similar challenges as their first-generation peers nationwide as they navigated their first year of college during the pandemic. As shown in Figure 3, nearly half of the 2020 cohort of Kessler Scholars surveyed in Spring 2021 reported increased concerns about their health and safety, ability to interact with peers, faculty, and staff, and future employment opportunities. Scholars also described difficulties adapting to remote learning environments and struggled with the lack of structure that in-person classes provided.

Figure 3: As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, to what extent, if any, has your concern about the following increased?

Source: Spring 2021 Kessler Scholars Survey (N=135)

One scholar observed, “I feel like I lagged behind a lot because of the online semester. I need to catch up and do well!” Another explained, “Because of COVID, online learning has been a bit of a challenge for some classes because it is harder to retain the information.” Financial pressures and family obligations added another layer of complexity to students’ experiences. A few scholars expressed concerns about paying bills and maintaining access to basic needs like food and housing, and some scholars had to take on increased care responsibilities and jobs to support their families, which limited their abilities to engage with online instruction.

Scholars reflected on their social and co-curricular experiences, noting decreased confidence in their abilities to interact socially with peers, faculty, and staff, feelings of anxiety and isolation, and the loss of community connections as effects of the pandemic. One scholar remarked, “It’ll make it difficult to know my fellow scholars in this program if I can’t interact with them more in person.” Some scholars also noted missed opportunities to engage in high-impact practices that have been linked to student success. As one scholar noted, “[COVID] has caused me to postpone in-person internship opportunities.”

These pandemic-related challenges were echoed several years later by alumni of the 2020 cohort who participated in a listening session led by the Collaborative in the spring of 2025. An alumnus recalled feeling uncertainty as campus closures were extended indefinitely. “I just remember the week just turned into two weeks, and the two weeks just kept stretching, and people never knew when it would stop.” Another alumnus remembered feeling anxious about taking college-level classes for the first time in virtual or hybrid learning environments and noted that the limited campus presence and lack of traditional college social experiences proved challenging for building campus connections:

We tried to go in person [for our class] a couple of times. I went one time, and after that one time, I got super sick, and I never went again. I remember I was really worried about not finding friends on campus and stuff like that, because no one was anywhere on campus.

The Kessler Scholars Program provided crucial community support during this time of disruption by providing virtual or online activities and structured programming that allowed scholars to maintain academic and social connections despite physical distance. As one Kessler Scholar reflected: “Kessler has been a wonderful community, and I’ve enjoyed getting to know other students in my cohort. As a student, the pandemic meant I couldn’t be on campus, so it was great to have a small group of people I could hang out with virtually and learn from.” Alumni explained how the shared experience of being first-generation and limited-income students navigating the same challenges created an immediate bond between the cohort and made virtual Kessler events feel like a safe space: “We’re all first-generation students. We all need financial aid. We’re all in the same boat in a lot of senses.”

Several alumni cited the one-on-one support provided by program staff during the pandemic as another key benefit of the program. Program staff served multiple roles, as academic advisors, emotional supporters, and connectors to campus opportunities and resources. Alumni expressed appreciation for the ability to schedule frequent virtual meetings with dedicated program staff to discuss both academic and personal topics, particularly given that their families could not always relate to their college experiences or challenges. One alumnus emphasized,

The best part was just how accessible the staff was to us. No matter how hard [program staff] tried, neither of them could help me with my

organic chemistry. But the fact that they were there, and they had so many appointments open, I could just hop on a Zoom and talk to them.

Adapting program supports for students in a time of crisis

The onset of the pandemic created unique challenges but also unexpected opportunities for the Kessler Scholars Collaborative as it began operations in early 2020. As campus activities shifted online, the Collaborative quickly pivoted to a virtual cross-institutional model that leveraged existing relationships and emerging technologies to continue programming and connections with students. Using interactive online workshops, video conferencing platforms, email, and phone calls, program staff led cohort meetings, workshops, and seminars while maintaining frequent individual contact with students. Staff at the University of Michigan launched the Kessler Scholars Ambassadors Program to support incoming students through virtual peer mentoring, while student advisory boards at Cornell University and the University of Michigan met jointly to share best practices. In addition to adapting programming at each campus, the Collaborative offered several virtual cross-site programs that allowed scholars to connect and build community across institutions, including a keynote by Wes Moore to mark the launch of the Collaborative, and other campus-led virtual cross-site programs: ‘Talking Across Difference’ at the University of Michigan, and ‘Building a LinkedIn Presence’ at Cornell University.

The Collaborative also facilitated cross-site collaboration and learning for program staff across institutions during this season. This included establishing a program development and support working group, which met virtually throughout the year to explore evidence-based practices for student recruitment and orientation, online learning strategies, peer mentorship models, and the development of student advisory boards. Beyond inter-campus connections, program staff collaborated with colleagues across various administrative units on their campus to support students’ emerging basic needs, such as helping students to secure laptops and reliable internet access to support remote learning, when needed.

As the Collaborative emerged from its first year and college campuses reopened in the fall of 2021, program leaders recognized the need to recreate crucial first-year experiences that returning students missed. This “Year 1 Take 2” programming included hosting campus tours and orientation experiences, and connecting students with campus offices and resources they had been unable to access during remote learning. Alumni noted that the return to in-person program events as the pandemic subsided helped to meet their basic needs and provided an emotional respite from academic pressures. One alumnus recalled, “There was a point where I was dealing with a lot of financial stuff that was going awry… and I struggled with being able to have food in my house. I remember going to the events, and it was some of the best food I’d had that week.” Once campus activities returned to the status quo, students were also able to connect in person with their peer mentors, and mentor-mentee relationships evolved organically into friendships and extended networks, fostering what one participant described as “almost a family feeling with Kessler.”

Campus spotlight: crisis response and innovation at the University of Michigan’s Kessler Scholars Program

When the University of Michigan announced its transition to remote learning in March 2020, the Kessler Scholars Program team faced an immediate challenge: how to maintain their high-touch, relationship-based support model for the 142 students served by the program who were relocating across the country, many returning to complicated home situations with limited resources.

Assessing student needs

Within a day of the university’s announcement, the program team developed and deployed a comprehensive needs assessment survey to identify students’ urgent concerns and immediate transition plans. Over the following two weeks, they also contacted each scholar served by the program. Students identified three primary areas of urgent concern: emergency financial needs due to unexpected travel costs and the sudden loss of on- and off-campus employment; technical barriers including lack of access to reliable computers and high-speed internet; and academic, social, and personal challenges including navigating online coursework for the first time, and losing peer connections, and access to campus resources such as libraries, gyms, and counseling services.

Connecting students to campus resources

The program team worked to address these immediate needs by connecting students with campus offices and resources to secure emergency support funds, free or reduced-cost internet service offers, and computer equipment.

Redesigning programming and outreach.

Beyond addressing these urgent basic needs, the program team adapted existing programming to address the academic, social, and personal concerns raised by students, while preserving the cornerstones of the program. These efforts included:

- Adapting existing support

- Restructuring weekly group and one-on-one student meetings to online formats and extending availability through the summer to provide consistent support during an uncertain time.

- Creating new programs

- Launching the Kessler Scholars Ambassadors initiative, which connected incoming first-year students with current students who served as one-to-one peer mentors, shared insights about university life, and helped students feel connected to the program community before their arrival on campus.

- Addressing missed opportunities

- Recognizing and honoring graduating seniors who missed traditional in-person commencement ceremonies through special editions of the student newsletter, social media features, and mailing gifts to graduates’ homes.

- Providing a second chance for students to experience missed opportunities once they returned to campus in fall 2021, including offering campus tours, orientation experiences and connections to campus resources that were not accessible during campus closures.

- Planning ahead

- Developing hybrid programming for the fall semester in response to anticipated restrictions on large gatherings and social distancing guidelines, such as restructuring the first-year seminar to support both in-person and virtual formats, and developing programming for smaller groups based on cohort year and shared interests.

Michigan’s experience demonstrates how comprehensive student support programs can innovate in ways that strengthen their core mission while also addressing crisis conditions. The virtual programming models developed during the pandemic continued to be used strategically post-COVID, particularly for supporting out-of-state students during summer months and for creating connections across the broader Kessler Scholars Collaborative network.

Tracking success outcomes of the 2020 cohort

The Collaborative’s early commitment to assessment and evaluation provided the data infrastructure needed to track the key experiences and completion outcomes of the 2020 cohort by the end of their college journey. We find evidence that the 2020 Kessler Scholars cohort achieved remarkable outcomes despite the extraordinary challenges they faced. As shown in Figure 4, the 2020 cohort achieved a 78 percent average four-year degree graduation rate across the six inaugural partner campuses, outperforming their first-generation peers at those same institutions, who graduated at a rate of 59 percent on average, and nearly tripling the historical average four-year graduation rate for first-generation students nationwide.

The 2020 cohort achieved a 78 percent average four-year degree graduation rate across the six inaugural partner campuses, outperforming their first-generation peers at those same institutions.

Figure 4: Percentage of Kessler Scholars (2020 cohort) who graduated within four years compared to peers at their institution and nationwide.[22]

Source: Kessler Scholars – Student Rosters (N = 135)

The external evaluation tracks psychosocial outcomes such as sense of belonging and feelings of mattering, which are positively correlated with persistence and completion, as well as other drivers of student success such as academic efficacy, and use of campus support resources.[23] As shown in Figure 5, 84 percent of the 2020 cohort of first-year Kessler Scholars surveyed in the spring of 2021 reported feeling like part of the community at their institutions, higher than reported measures for comparable populations of first-year students surveyed across the country in 2020.

Figure 5: Percentage of first-year Kessler Scholars (2020 Cohort) who agreed with the survey statement “I felt like part of the community at my institution,” compared to peers nationwide.[24]

Source: Spring 2021 Kessler Scholars Survey (N = 130)

By the end of their college journey in the spring of 2024, 83 percent of graduating students from the 2020 cohort on average reported a sense of belonging within the small, tight-knit program communities designed for first-generation students (see Figure 6). They also reported a greater sense of belonging within the program compared to the institution as a whole (77 percent of respondents on average).

Figure 6: Sense of belonging of graduating seniors in the 2020 cohort.

Source: Spring 2024 Kessler Scholars Survey (N = 71)

Additionally, 90 percent of graduating seniors who responded to the survey were satisfied with their program experience, and 96 percent would recommend the program to other students from similar backgrounds (See Figure 7).

Figure 7: Program experiences of graduating seniors in the 2020 cohort.

Source: Spring 2024 Kessler Scholars Survey (N = 71)

Promising practices for supporting first-generation students through crisis

Amidst the crisis and uncertainty of the pandemic, the comprehensive student support offered by the Kessler Scholars Program helped first-generation students persist, thrive, and succeed. The program adaptations developed during the pandemic provide insights for institutions and programs seeking to effectively support first-generation and underserved students during personal crises or disruptions to campus activities due to health crises, civic conflict, natural disasters, or economic downturns. While these lessons emerged from crisis conditions, many of these practices reflect core principles that institutions should implement routinely, not just during emergencies, to better support vulnerable populations. Key lessons learned include:

While these lessons emerged from crisis conditions, many of these practices reflect core principles that institutions should implement routinely, not just during emergencies, to better support vulnerable populations.

Provide comprehensive support. The combination of academic, personal, and basic needs support provided through one-on-one contacts, cohort programming and instruction, and emergency funding addressed the multifaceted challenges students faced.

Invest in staff capacity. Strong staff-student relationships established before the pandemic and reinforced via virtual support served as a protective factor during periods of uncertainty and encouraged students to reach out for additional support. Dedicated, trained staff who can build relationships with students and facilitate connections to campus resources are essential for program success.

Prioritize community and connection. Creating environments where students feel they belong and are cared for has proven critical to their success. Virtual mentoring and cohort-based programming helped students connect with peers who shared similar backgrounds and experienced similar challenges, reducing feelings of isolation on campuses where students were often in the minority.

Plan crisis response strategies. Institutions need to develop adaptive capacity that allows them to quickly modify service delivery without compromising effectiveness. Crisis preparedness should be built into standard operating procedures to maintain service delivery. This includes maintaining emergency funding that can be flexibly allocated based on emerging needs, training faculty and staff to support students in various modalities (in-person, hybrid, or virtual), developing communication protocols, and investing in robust technology infrastructure.

Leverage technology to expand access. Virtual technologies such as online learning platforms and videoconferencing tools can be used to enhance rather than replace in-person interactions, particularly for students who may face cost, transportation, scheduling, or other barriers to accessing campus-based services.

Cultivate learning networks for practice-sharing. The collaborative model that allows for shared learning and resource development across institutions shows promise for scaling effective practices. Additionally, institutions should support and connect staff across campus offices and programs to improve the efficiency of service delivery and prevent siloed operations.

Integrate continuous assessment and learning. Integrating assessment from the start of program implementation can help programs track program outputs and student experiences, and guide program improvement. The Collaborative’s early commitment to assessment provided the data infrastructure needed to understand students’ needs and track key program outcomes over time.

Conclusion

Our analysis reveals several key findings. Despite facing unprecedented challenges during the pandemic, the 2020 Kessler Scholars cohort achieved a remarkable 78 percent four-year graduation rate, significantly outperforming their first-generation peers at the same institution. The program’s rapid pivot to virtual programming while maintaining core components—individualized staff support, cohort-based community building, and comprehensive wraparound services—proved effective in sustaining student engagement and success. Scholars reported a strong sense of belonging both within the program (83 percent) and their institutions (77 percent), with 96 percent willing to recommend the program to other first-generation students.

The example of the Kessler Scholars Program offers compelling evidence that comprehensive cohort-based student support programs can successfully help first-generation students not only survive but thrive during extraordinary periods of disruption.

The example of the Kessler Scholars Program offers compelling evidence that comprehensive cohort-based student support programs can successfully help first-generation students not only survive but thrive during extraordinary periods of disruption. Rapid program adaptations—from leveraging technology for virtual programming to reimagining how student connections could be maintained despite physical distance—transformed existing practices while preserving the core program components most strongly linked to student success. This brief contributes to the knowledge base about effective crisis response in higher education. Prior studies indicate that other comprehensive student success initiatives across the country similarly adapted their implementation models during the pandemic, leading to strategic innovations in advising delivery, more flexible enrollment policies that accommodated part-time students, and enhanced crisis support systems.[25] The lessons learned from the Kessler Scholars Program offer a roadmap for designing resilient student success systems that are robust to various forms of disruption and responsive to the evolving higher education landscape.

Acknowledgements

The author sincerely appreciates the Kessler Scholars and alumni who participated in the various surveys, focus group discussions, and listening sessions that provided data for the assessment of the program, and the program staff on each campus who facilitated assessment activities and contributed insights. The author thanks Gail Gibson, Kristen Glasener, and Shakima Clency for their insights into the earlier years of the Collaborative’s work and feedback on the draft. Thanks are also due to Elizabeth Pisacreta for thoughtful feedback on this work. Any errors or omissions remain the fault of the author.

The evaluation of the Kessler Scholars Program is made possible through the generous support of Bloomberg Philanthropies and the Judy and Fred Wilpon Family Foundation. Views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the positions or policies of the funders.

Endnotes

- Michael S. Kofoed, Lucas Gebhart, Dallas Gilmore, and Ryan Moschitto, “Zooming to Class? Experimental Evidence on College Students’ Online Learning During Covid-19,” American Economic Review: Insights 6, no. 3 (2024): 324-340, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles/pdf/doi/10.1257/aeri.20230077; Lindsay McKenzie, “Back on Track: Helping Students Recover from COVID-19 Learning Disruption,” Inside Higher Ed, 2021, https://www.luminafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/deep-dive-back-on-track.pdf. ↑

- National Survey of Student Engagement, “Engagement Insights: Survey Findings on the Quality of Undergraduate Education– Annual Results 2021,” Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research, 2022, https://nsse.indiana.edu/research/annual-results/2021/2021_annual_results_booklet.pdf. ↑

- Krista Soria, “Basic Needs Insecurity and College Students’ Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Journal of Postsecondary Student Success 2, no. 3 (2023): 23-51.https://journals.flvc.org/jpss/article/view/130999/137302; Margaux Cameron, T. Austin Lacy, Peter Siegel, Joanna Wu, Ashley Wilson, Ruby Johnson, Rachel Burns, and Jennifer Wine, “2019-20 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS: 20): First Look at the Impact of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic on Undergraduate Student Enrollment, Housing, and Finances (Preliminary Data), NCES 2021-456,” National Center for Education Statistics, 2021, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED613348.pdf; “The Impact of COVID-19 on College Student Well-Being,” The Healthy Minds Network, and American College Health Association, July 9, 2020, https://healthymindsnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Healthy_Minds_NCHA_COVID_Survey_Report_FINAL.pdf. ↑

- Robert Kelchen, Dubravka Ritter, and Douglas Webber, “The Lingering Fiscal Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Higher Education,” Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, 2021, https://www.philadelphiafed.org/-/media/FRBP/Assets/Consumer-Finance/Discussion-Papers/dp21-01.pdf; “Higher Education and State Budgets: First Lessons from the Pandemic,” The Institute for College Access & Success, November 30, 2021, https://ticas.org/affordability-2/student-aid/federal-state-partnerships/higher-education-and-state-budgets-first-lessons-from-the-pandemic/ ↑

- Jennifer Engle and Vincent Tinto, “Moving Beyond Access: College Success for Low-Income, First-Generation Students,” Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education, 2008, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED504448.pdf; Susan Dynarski, Aizat Nurshatayeva, Lindsay C. Page, and Judith Scott-Clayton, “Addressing Nonfinancial Barriers to College Access and Success: Evidence and Policy Implications,” NBER Working Papers Series, no. 300054 (January 2023), https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w30054/w30054.pdf; H. J. Holzer and Sandy Baum, Making College Work: Pathways to Success for Disadvantaged Students (Brookings Institution Press, 2017), https://www.brookings.edu/books/making-college-work/. ↑

- Krista M. Soria, Bonnie Horgos, Igor Chirikov, and Daniel Jones-White, “First-Generation Students’ Experiences During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” SERU Consortium, University of California – Berkeley and University of Minnesota, 2020, https://d1y8sb8igg2f8e.cloudfront.net/2020_First-Generation_Students_Experiences_During_the_COVID-19_Pandemic.pdf. ↑

- RTI International, “First-generation College Students’ Experiences During the Early COVID-19 Pandemic: January to June 2020,” Washington, DC: FirstGen Forward, 2023, https://46502496.fs1.hubspotusercontent-na1.net/hubfs/46502496/FGF%20Fact%20Sheets/15405_NASPA_FactSheet-02.pdf ↑

- Núria Rodríguez-Planas, “Hitting Where It Hurts Most: COVID-19 and Low-Income Urban College Students,” Economics of Education Review 87 (2022): 102233, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0272775722000103. ↑

- At the time of its launch in 2020, the Kessler Scholars Collaborative consisted of six inaugural institutions–the University of Michigan, Cornell University, St. Francis College, Queens College, Syracuse University, and Johns Hopkins University–the latter three of which launched the program operations with their very first cohort of students in the fall of 2020. ↑

- Full details of our evaluation approach and data sources can be found here: “Kessler Scholars Collaborative Evaluation Plan Brief,” Ithaka S+R and the Kessler Scholars Collaborative, https://sr.ithaka.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Kessler-scholars-collaborative-evaluation-plan-brief.pdf; Ifeatu Oliobi, Dillon Ruddell, Caroline Doglio, “Tailored Support for First-Year, First-Generation College Students: Findings from an Evaluation of the Kessler Scholars Program,” Ithaka S+R, December 19, 2024, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.321866. . ↑

- The Fall 2020 and Spring 2021 Kessler Scholars Surveys were conducted by the CEDER evaluation team. See more: “Kessler Scholars Collaborative,” University of Michigan Marsal Family School of Education, https://marsal.umich.edu/projects/kessler-scholars-collaborative. ↑

- The initial evaluation of the program was led by the Center for Education Design, Evaluation, and Research (CEDER) at the University of Michigan. See https://marsal.umich.edu/projects/kessler-scholars-collaborative for details of this evaluation. ↑

- “Proven Model for First-Generation Student Success Expands to 10 Additional Four-Year Institutions Nationwide with a Five-Year, $10 Million Investment,” American Talent Initiative and Kessler Scholars Collaborative, April 12 2022, https://americantalentinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Announcement-Press-Release_v2.pdf. ↑

- Lia Lumauig and Ifeatu Oliobi, “Announcing a New Partnership with the Kessler Scholars Collaborative,” Ithaka S+R, June 6, 2022, https://sr.ithaka.org/blog/announcing-a-new-partnership-with-the-kessler-scholars-collaborative/. ↑

- “Defying the Odds,” Kessler Scholars Collaborative, May 2, 2024, https://kesslerscholars.org/defying-the-odds/. ↑

- Jennifer Ma and Matea Pender, “Education Pays 2023: The Benefits of Higher Education for Individuals and Society,” College Board, 2023, https://research.collegeboard.org/media/pdf/education-pays-2023.pdf. ↑

- RTI International, “First-Generation College Students in 2020: Demographic Characteristics and Postsecondary Enrollment,” Washington, DC: FirstGen Forward, 2023, https://46502496.fs1.hubspotusercontent-na1.net/hubfs/46502496/FGF%20Fact%20Sheets/15405_NASPA_FactSheet-01.pdf ↑

- RTI International, “First-Generation College Students’ Achievement and Federal Student Loan Repayment,” Washington, DC: FirstGen Forward, 2024, https://46502496.fs1.hubspotusercontent-na1.net/hubfs/46502496/FGF%20Fact%20Sheets/15405_FactSheet-05_final.pdf. ↑

- Ifeatu Oliobi, Caroline Doglio, and Dillon Ruddell, “Evaluating the Kessler Scholars Program: Findings from the Academic Year 2022-23,” Ithaka S+R, July 11, 2024, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.320987;Sarah E. Whitley, Grace Benson, Alexis Wesaw, “First-Generation Student Success: A Landscape Analysis of Programs and Services at Four-Year Institutions,” NASPA Student Affairs Administration in Higher Education, 2018, https://www.luminafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/first-gen-student-success.pdf. ↑

- Sarah Reber, “Supporting Students to and Through College: What Does the Evidence Say?” Brookings Institution, December 11, 2024. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/20241211_CESO_Reber_CollegeSupports_1c.pdf.Rachel Fulcher Dawson, Melissa S. Kearney, James X. Sullivan, “Comprehensive Approaches to Increasing Student Completion in Higher Education: A Survey of the Landscape,” National Bureau of Economic Research, February 2021, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w28046/w28046.pdf. ↑

- Student enrollment numbers presented here are preliminary and based on program rosters available at the time of analysis. Final enrollment figures are subject to verification through ongoing data reconciliation efforts with institutional research offices and will be updated in spring 2026. ↑

- Four-year graduation rates for Kessler Scholars are provisional, based on enrollment data submitted through ongoing program tracking. Aggregate graduation rates for the comparison group—first-generation students at the inaugural partner institutions—are computed based on the data submitted by institutions as part of their 2025 grant renewal applications. The national average four-year graduation rate for first-generation students is drawn from: Linda DeAngelo, Ray Franke, Sylvia Hurtado, John H. Pryor, and Serge Tran, Completing College: Assessing Graduation Rates at Four-Year Institutions (Los Angeles: Higher Education Research Institute, UCLA, 2011) https://heri.ucla.edu/DARCU/CompletingCollege2011.pdf. ↑

- Alexa Silverman, “What Universities Can Do to Advance Student Belonging?” EAB Student Success Blog, 26 October 2021, https://eab.com/resources/blog/student-success-blog/universities-advance-student-belonging. ↑

- The national averages are obtained from the National Survey of Student Engagement (2020) Sense of Belonging. NSSE Interactive Reports. Retrieved from “NSSE Sense of Belonging: An Interactive Display,” https://tableau.bi.iu.edu/t/prd/views/NSSESenseofBelonging/NSSESenseofBelonging?%3Aembed=y&%3AisGuestRedirectFromVizportal=y. The 2021 Kessler Scholars Survey did not disaggregate between cohorts for one inaugural institution, so first-year survey estimates may include some second-year students for that institution. ↑

- The Institute for College Access & Success, “How Comprehensive Student Success Programs Learned and Adapted Through COVID-19,” July 2022, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED623262; Lopez Salazar, Andrea, Lauren Pellegrino, and Lindsay Leasor, “How Colleges Adapted Advising and Other Supports During COVID-19 Shutdowns,” Community College Research Center, Teachers College, Columbia University, September 16, 2020, https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/easyblog/colleges-adapted-advising-covid-supports.html. ↑