Why Are Libraries Changing Their Look?

Strategies Driving the Evolution of Academic Libraries

Yesterday, Teresa Watanabe at the Los Angeles Times reported on universities across the country redesigning libraries for the 21st century by focusing less on books and more on space. Findings from the Ithaka S+R Library Survey 2016, which queried library deans and directors across the United States on their strategy and priorities, demonstrate the ways that these libraries are evolving, and confirm much of the anecdotal evidence provided by the LA Times.[1] Throughout our national survey findings, we are seeing evidence of collections being digitally transformed, policies for de-accessioning print resources being developed, and resources increasingly being devoted towards the development and bolstering of services.

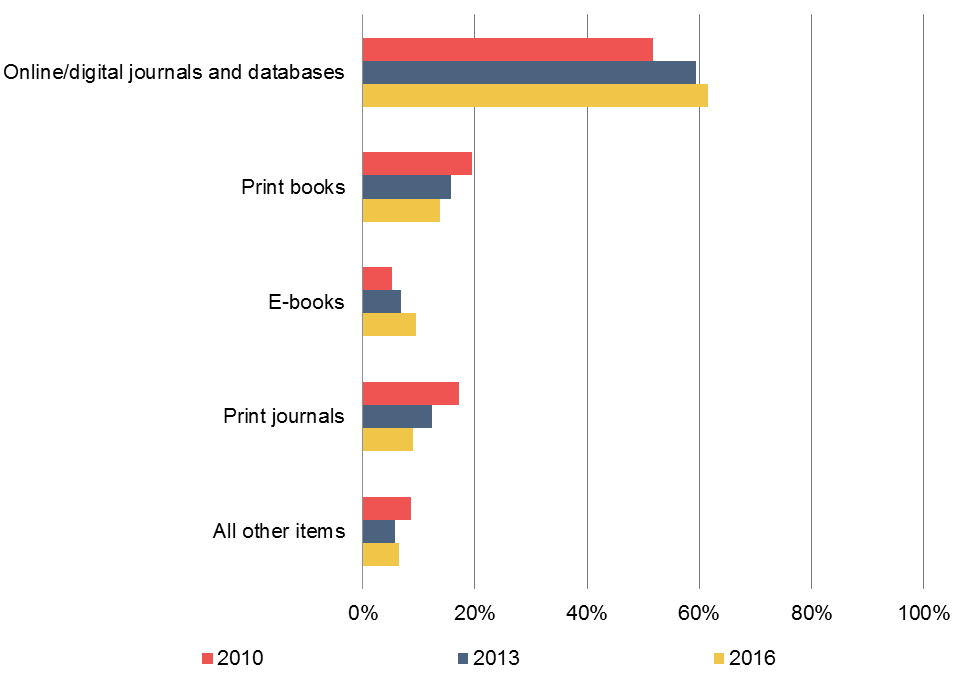

As the digital revolution, as the LA Times calls it, is dramatically changing the use of libraries on college and university campuses, library leaders are continuing to increase spending on electronic resources and decrease spending on print resources. Results from each cycle of the Library Survey have clearly demonstrated this transitioning from print to electronic – and these library leaders expect spending to continue in this direction.

Figure 1: What percentage of your library’s materials budget is spent on the following items? Average estimated percentage of budget spent on each type of item.

Further emphasizing this shift towards electronic resources, many libraries are developing policies for de-accessioning print materials that are also available digitally. Since the previous cycle of the Library Survey in 2013, the share of library directors who have developed these policies, across varied types of institutions, has nearly doubled – from roughly one in three to approximately six in ten.

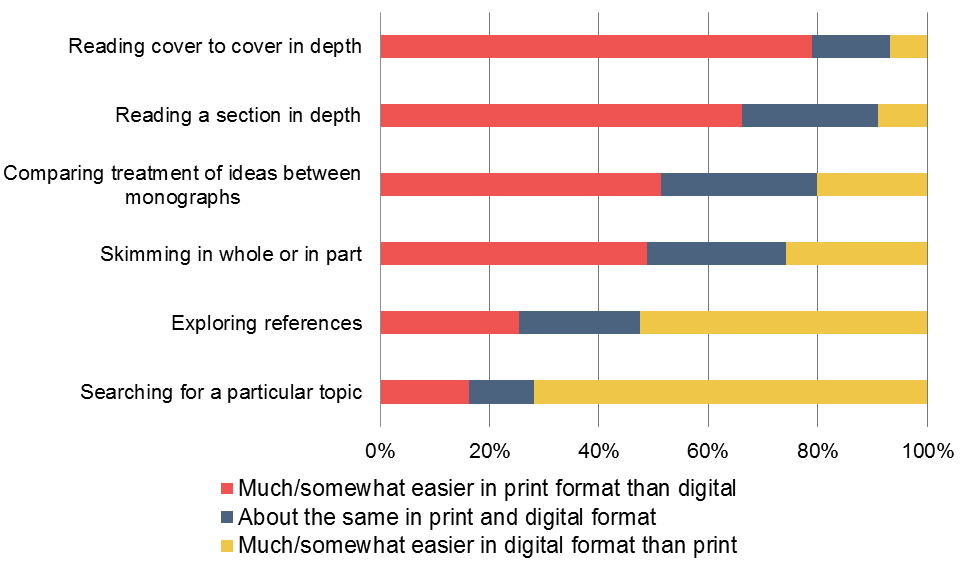

Meanwhile, while faculty members appear to be fairly comfortable with the transition from print to electronic for journals, there appears to be less of a clear trend towards a format transition for monographs, especially for scholars in the humanities. Findings from the Ithaka S+R US Faculty Survey 2015 indicate the varied ways that scholars prefer to use monographs digitally and in print; overall, print is generally preferred, but there are a number of activities for which respondents were divided in their preferences. And, in fact, we observed in this most recent study of faculty members that there was a curious shift in these preferences; if anything, their preference for using print scholarly monographs in various ways had generally increased since the previous cycle of the survey in 2013.

Results from these two studies illustrate much of the tension highlighted by the LA Times – while libraries have rapidly developed policies for de-accessioning print materials over the past few years, faculty members’ needs in many ways have not changed, and a dual format environment for monographs may continue to be necessary for some time.

Figure 2: Below is a list of ways you may use a scholarly monograph. Please think about doing each of these things with a scholarly monograph in print format or in digital format, and use the scales below to indicate how much easier or harder it is to perform each activity in print or digital format. Percent of faculty member respondents who indicated that each of these practices is easier or harder in print or digital formats.

Meanwhile, library directors are anticipating increased resource allocation towards services. These leaders predict the most growth for positions related to teaching and research support. In forecasting changes to employee positions, library directors specifically anticipate the most growth in the next five years for positions in instruction, instructional design, and information literacy, as well as those in specialized faculty research support.

Further, many library leaders expressed interest in investing additional funds towards new employees, redefined positions, and facilities expansions and renovations. Many of these survey findings demonstrate this redirection of the library – from serving principally as collection builders and content providers to supporters of teaching, learning, and research.

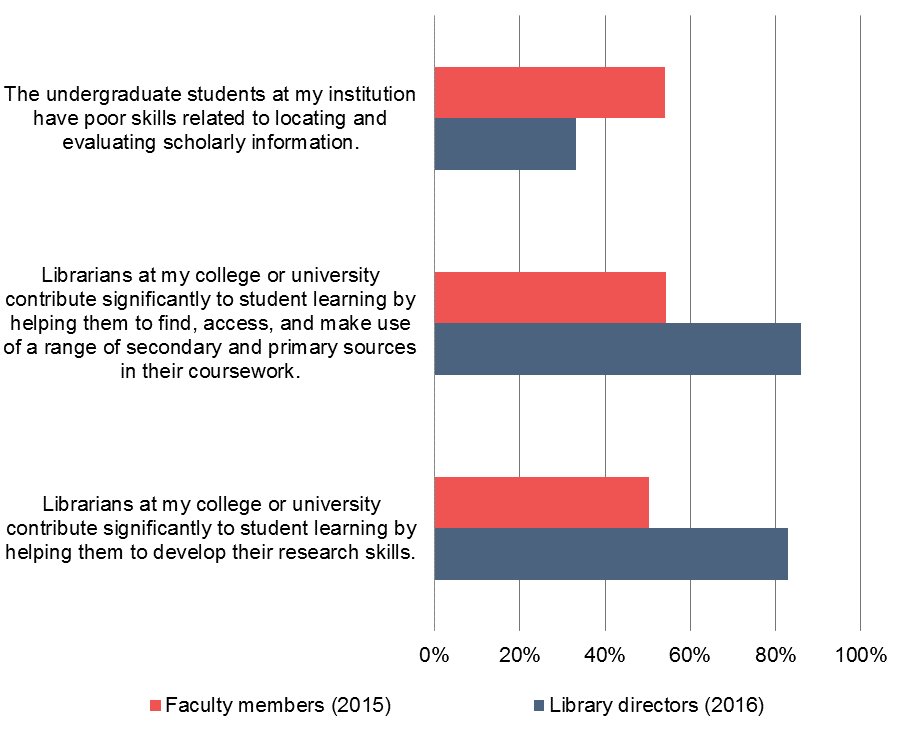

And while supporting student success remains a priority for nearly all of these leaders, many have not clearly articulated how their libraries contribute towards student success, and faculty members at their institutions often do not recognize these contributions. Findings from the Ithaka S+R US Faculty Survey 2015 alongside those from the Library Survey 2016 make clear this disconnect; while faculty members are more likely than library directors to perceive that their students have poor research skills, they are considerably less likely to agree that librarians at their college or university contribute to student learning by helping them to develop research skills and find, access, and make use of resources.

Figure 3: Please use the 10 to 1 scales to indicate how well each statement below describes your point of view. Percentage of respondents who strongly agreed with each statement.

It is evident in the findings from both of these studies and in many of the narratives provided by the LA Times that academic libraries are navigating new strategic direction in a variety of ways. Academic libraries must balance the unique needs of both faculty members and students while simultaneously dealing with increasing resource constraints as they are simultaneously shifting in their investments for the future. And while this transition is proving to be a serious challenge for many of these organizations, as our findings suggest, understanding and supporting the needs of these diverse stakeholders will be necessary for the success of the academic library in the 21st century.

- In fall 2016, we invited library deans and directors at not-for-profit four-year academic institutions across the United States to complete the survey, and we received 722 responses for a response rate of 49 percent. ↑