Advancing Student Success at High-Graduation-Rate Institutions

Insights from the American Talent Initiative Student Success Research Grant Program

-

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- First-Year Seminar Self-Assessment Tool for Supporting Students from Low-Income Backgrounds

- From Community College to Selective Four-Year College: Experiences of Transfer Students

- How Does Tuition-Free Aid Support Low-Income Students at Selective Institutions? Understanding the Effects of Bucky’s Tuition Promise on Persistence, Completion, and Debt

- Improving First-Year Outcomes for First-Generation Students through Summer Engagement Programs

- SEEK-ing a Better Future: Supporting College Success for Economically and Educationally Disadvantaged Students

- Understanding the Use of Basic Needs Services to Better Serve College Students

- Endnotes

- Introduction

- First-Year Seminar Self-Assessment Tool for Supporting Students from Low-Income Backgrounds

- From Community College to Selective Four-Year College: Experiences of Transfer Students

- How Does Tuition-Free Aid Support Low-Income Students at Selective Institutions? Understanding the Effects of Bucky’s Tuition Promise on Persistence, Completion, and Debt

- Improving First-Year Outcomes for First-Generation Students through Summer Engagement Programs

- SEEK-ing a Better Future: Supporting College Success for Economically and Educationally Disadvantaged Students

- Understanding the Use of Basic Needs Services to Better Serve College Students

- Endnotes

Introduction

The American Talent Initiative’s Student Success Research Grant Program supported research studies aimed at deepening our understanding of the institutional practices and strategies that can improve student success at high-graduation-rate institutions. The findings will offer actionable recommendations for supporting lower-income students, while raising awareness of the challenges that they—and the institutions that serve them—continue to face. Full manuscripts will be published this summer in the Peabody Journal of Education. These short briefs aim to equip institutional leaders with key research insights, empowering them to implement strategies that foster meaningful, lasting change.

These research grants were made possible due to generous funding from Bloomberg Philanthropies.

First-Year Seminar Self-Assessment Tool for Supporting Students from Low-Income Backgrounds

Morgan State University

Authors: Christine Harrington, Michael Sparrow, and Karen Irving

Our Why: Students from Low-Income Backgrounds Have Low College Completion Rates

Students from low-income backgrounds comprise almost a third of college enrollment, but many colleges are ill-prepared to support this significant population of students well. This misalignment between the unique needs of students from low-income backgrounds and the strategies colleges use to support incoming students leads to unacceptably low persistence and graduation rates compared to their better-resourced peers. In fact, Pell Grant recipients had 7.8-14.2 percent lower completion rates than their better-resourced peers.[1]

Our Focus: The First-Year Seminar

First-Year Experience seminars (FYS) are a high-impact practice that are offered at most institutions. Based on recent national survey data, 77 percent of colleges and universities in the United States offer a first-year seminar.[2] Rather than adding services to support students from low-income backgrounds, we wanted to help institutions strengthen existing practices. We believed that assessing and improving the FYS would be an excellent, systemic way to support large numbers of incoming students from low-income backgrounds.

Our Goal: Develop a First-Year Seminar Self-Assessment Tool

We wanted to develop a tool that first-year seminar directors and their teams could use to engage in a self-assessment and reflection process about how well their first-year seminar course was supporting students from low-income backgrounds. We hoped that engaging in this process would help institutions determine the course strengths and areas for improvement.

Our Approach: Using Design Thinking to Enhance the First-Year Seminar Self-Assessment Tool

We wanted to rely not only on the literature but also on the expertise of practitioners in the field as we sought to understand how colleges can better support students from low-income backgrounds in the first year of college. We believed that practitioner perspectives from the field were critical because those working with students from low-income backgrounds in the first year have a strong understanding of the challenges they face and how a first-year seminar could best support these students during their transition to college.

Because we believed gaining user perspectives would strengthen the tool, we opted to use a design thinking process. Design thinking involves five stages: empathize, define, ideate, prototype, and test.[3] At conferences, we listened and empathized with practitioners around the challenges they faced and then defined the problem that students from low-income backgrounds have lower retention and completion rates than their peers. We then determined that the first-year seminar would be the focus of the project. Before developing the prototype, we conducted literature reviews on students from low-income backgrounds,[4] as well as on first-year seminars.[5] Next, we conducted focus groups to gather practitioner insights into the needs of students from low-income backgrounds and learn how institutions could best support this population through the first-year seminar.[6] We recruited practitioner volunteers, being mindful of creating a broad representation of perspectives by university type (two-year, four-year, public, private, HBCU) and by the role of volunteers (faculty, coordinator, director, senior administrators) through listservs, social media, and our professional networks. We conducted two hour-long focus groups with eight participants each. Based on the data from these three sources, the two literature reviews, and the focus groups, we developed the prototype FYS self-assessment tool.

For the testing phase of the design thinking process, we recruited eight practitioners to participate in two rounds of interviews. The first iteration of the instrument was shared with these eight practitioners. All participants had experience working with students from low-income backgrounds and with the first-year seminar. During one-hour-long interviews, each practitioner provided detailed feedback on the tool. The feedback focused on the strengths of the tool, ways to improve the tool, and their thoughts on how the tool could best be used by institutions. We evaluated and implemented this feedback into an updated version of the tool, which was then circulated to the same eight practitioners for a second round of feedback. This time, we asked participants to use the tool rather than just review it. The second round of feedback informed the finalized version of the instrument.

Our Product: The First-Year Self-Assessment Tool

The first-year seminar self-assessment tool has three sections.

- The first section is to be completed by first-year seminar directors or leadership teams. The leader-focused section has 89 items related to teaching practices and institutional practices.Teaching practices include items related to

-

- developing a sense of community,

- resources,

- academic strategies,

- career,

- mindsets, and

- assignments.

Institutional practices include items related to

-

- professional learning for faculty and peer leaders,

- assessment, and

- institutional efforts.

- The second section is to be completed by faculty. The faculty-focused section only includes the teaching practice items.

- The third section is to be completed by the first-year seminar director and leadership teams. In this section, first-year seminar directors and their teams are asked to summarize the strengths of the course, identify areas for improvement, and determine an action plan for prioritized improvement areas. The tool can be accessed at https://www.scholarlyteaching.org/fye.

We recommend that first-year seminar directors first determine who should be involved in the assessment process and consider including professionals who will bring varied lenses to the work. To gather information about current practices and to determine faculty development needs, we also encourage full and part-time faculty teaching the first-year seminars to complete the tool.

Strategies for assessment and implementation are context-specific and depend on many factors such as financial resources, availability of personnel, and institutional strategic planning. Small review teams can focus on one of the areas in the tool or even specific items within an area as either a one-time exercise or as part of a multi-year strategy that expands into other areas of the tool incrementally. Alternatively, colleges can opt for larger adoption strategies from the start that involve many or all of the areas of the self-assessment tool.

In either case, after all the key stakeholders have completed the tool, the first-year seminar director can compile the findings and bring them to a team meeting for discussion. The teams can then determine the desired strategy and tactics aimed at better serving students from low-income backgrounds through the first-year seminar.

From Community College to Selective Four-Year College: Experiences of Transfer Students

Santa Clara University and San Jose College

Authors: Laura Nichols, William Garcia, Alexis Rivera, and Iliana Rodriguez

Background

In the United States, most students start their college education in local community colleges. Of these students, a very small proportion ever transfer to a four-year, private selective college. This research focuses on understanding the factors that community college students consider when deciding where to transfer and explores the experiences of students once they have transferred to a four-year selective college. The ultimate purpose is to use the findings to help selective colleges better meet the needs of transfer students.

Methods

For this project, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 16 transfer-intending students at one community college and 15 students who had transferred to a selective four-year college from 10 different community colleges. We also analyzed publicly available data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) and the College Scorecard to understand the demographics of students at the community colleges local to the selective college.

Key Findings

Community colleges are key sources for selective colleges to make sure they are reaching academically eligible local students as well as doing their part to contribute to bachelor completion goals of states and localities. Community colleges give students a “second chance” to continue to build their skills, recover academically from challenging high school experiences or sports injuries, and imagine themselves in prestigious colleges. Two transfer students at the selective college said that in high school and early in their time at community college they never would have imagined attending the selective four-year. The prestige, cost, and status seemed out of reach for them. But as they gained skills and did well at their community college, their aspirations changed.

Though academically eligible, community college students did not really consider applying to the selective four-year college. They all mainly planned on going to the nearest California State University (CSU), which they said would be very much like attending their community college. For the students at the selective four-year, an individual invitation or a notice about a scholarship helped them to consider applying and ultimately attend the selective four year. Students also needed help navigating the application and understanding financial aid offers.

The most important considerations in selecting a college were location, cost, flexibility, and comfort level. Many transfer students want to be able to continue to live with family, to keep their current jobs, and to move from full- to part-time enrollment when family or financial needs become acute. A father who needed to take classes after his full-time work was done and kids were picked up from school said, “Usually I work full time, and I take night classes. That’s my regular schedule. I work Monday through Friday, that’s basically 9 to 5, but I usually get off at like 3. And then I would go to school from like 6 to 9. Depends on the class. Sometimes they start earlier” (CC114). Students at the local community colleges had a higher mean age than those at the selective college.

Students valued many aspects of the selective college. A number of students mentioned the small class sizes as well as the ability to get help and support. Four of the 15 interviewees at the selective four-year college said they just walked into the admissions office to get help understanding their financial aid offer: “I ended up visiting (the S4Y) and also going to the Admissions office to kind of ask them to like, help me understand my financial aid and everything because I couldn’t really understand it. And so I went in person, and they were very nice and very helpful in explaining it to me (S4Y208).” This personalization continued once enrolled, “A big difference I’ve noticed is really small class sizes. At least, that’s the positive one—smaller class sizes. I can talk to teachers more. A lot of stuff that just stems off that” (S4Y205).

Culture shock and adjustment to the four-year meant that commuting was preferable for some students. One transfer student at the selective four-year college said, “It’s just nice knowing that at the end of my last class I get to go home, you know, to my family. And honestly, I think if I had lived on campus I think I would be having a much worse time” (S4Y208). A number of transfer students struggled with the cultural and demographic differences between their community college and the four-year. For some this contributed to not feeling comfortable speaking up in class and students worried that this negatively affected their grades.

Most students were doing fine academically, though some struggled. When asked more about the difference between the way courses were taught at his community college versus the selective four-year college, a Computer Science major said, “(at my CC) they kind of just walk you through the examples and explain everything. Once, everybody kind of felt that they understood, then they moved on (to a new topic). Here it was just like, Go go, go!” (S4Y207). He did not feel comfortable asking questions during class because he felt like he was the “only one” struggling.

For students who had transferred to the four-year selective college, having to work plus school was extremely challenging. The student who struggled the most was a business major who also had to support her parents, paying many of the household expenses as well as unexpected health expenses and car repairs. The student worked as much as she could, especially in the summer, but worried that she was behind their peers in getting the right types of internships and experiences to ultimately get a higher paying job.

Recommendations for Selective Colleges

- Enrollment Management: Selective colleges should reach out to community college students with offers of scholarships, assistance with applications, transparency around unit transfer loss or limits, and help with financial aid offers. College admission and financial aid assistance should be advertised and virtual meetings offered for prospective applicants. Building partnerships with community colleges and collaborative programming and community events and tours as well as access to academic programs will help the selective four-year college be more accessible and familiar to local community college students.

- Institutional Research and Undergraduate Studies: Annually examine and present to the selective four-year college campus current IPEDS data on local community colleges to help staff and faculty understand the demographics of potential transfer students. Inventory academic policies and necessary support if demographics are different.[7] Track the success of community college transfer students.

- Student Services: Orientation and summer bridge programs are helpful. Transfer students suggested an orientation only for transfer students as well as opportunities to tour campus and find their classes before the start of the term. Further, students asked for introductions and easy access to key people on campus that could help them navigate the school as well as check-ins with advisors often during the first year post transfer.

- Academic Departments: Determine transferable major courses at the community college for ease of transfer as well as consider dual enrollment options for prospective transfer students from local community colleges. Invite enrolled transfer students in the major to mentor new transfer students and create courses that allow them to meet one another. Train faculty about the demographics of transfer students and in inclusive pedagogies.[8]

- Career Services: Transfer students need help to capitalize on the skills they have from all their previous work experience, but also assistance in getting the experience and opportunities necessary to transition to their desired career post graduation.

How Does Tuition-Free Aid Support Low-Income Students at Selective Institutions? Understanding the Effects of Bucky’s Tuition Promise on Persistence, Completion, and Debt

University of Wisconsin-Madison

Author: Amberly B. Dziesinski

Bucky’s Tuition Promise is a financial aid program covering four years of tuition and fees for University of Wisconsin-Madison students from families with incomes below a specified adjusted gross income (AGI).

Selective colleges typically have more resources to help students succeed in college, yet disproportionately few students from low-income backgrounds attend these institutions.[9] To address this problem, the University of Wisconsin-Madison (UW-Madison) launched “Bucky’s Tuition Promise” (BTP) in 2018 to send a simple and clear message to the state’s lowest-income students: tuition and fees will be free for four years if your family income is below $56,000 (since increased to $65,000).

BTP was designed to reduce barriers to participation, including:

- Basing eligibility on AGI, which families are likely more aware of than Student Aid Index (SAI)

- Automatically applying aid to eligible students if they file the FAFSA

- Guaranteeing eligibility for four years, even if a student’s income changes

BTP is a last-dollar program, meaning all other gift and scholarship aid is applied to a student’s tuition bill first, and BTP covers the difference to make the tuition balance zero. Some BTP-eligible students receive zero dollars from BTP because their tuition and fees are covered from other sources including state and federal aid and scholarships. These students are still considered part of the BTP program, a designation that matters for outreach efforts, such as voluntary programs on financial health, and future awarding if other aid changes.

Our findings show that BTP increases student retention, has no identifiable effect on graduation, and may decrease debt.

Prior research shows BTP-eligible students are more likely to enroll at UW-Madison and receive higher grant aid packages.[10] The current study assessed longer term outcomes including retention into the second year, debt accumulated within four years, and graduation within four years. Table 1 shows average differences between BTP participants and a comparison group of non-participants with AGIs below $120,000 in the Fall 2018 and Fall 2019 cohorts. BTP students’ retention and graduation rates are similar to non-participants, while debt is substantially lower on average.

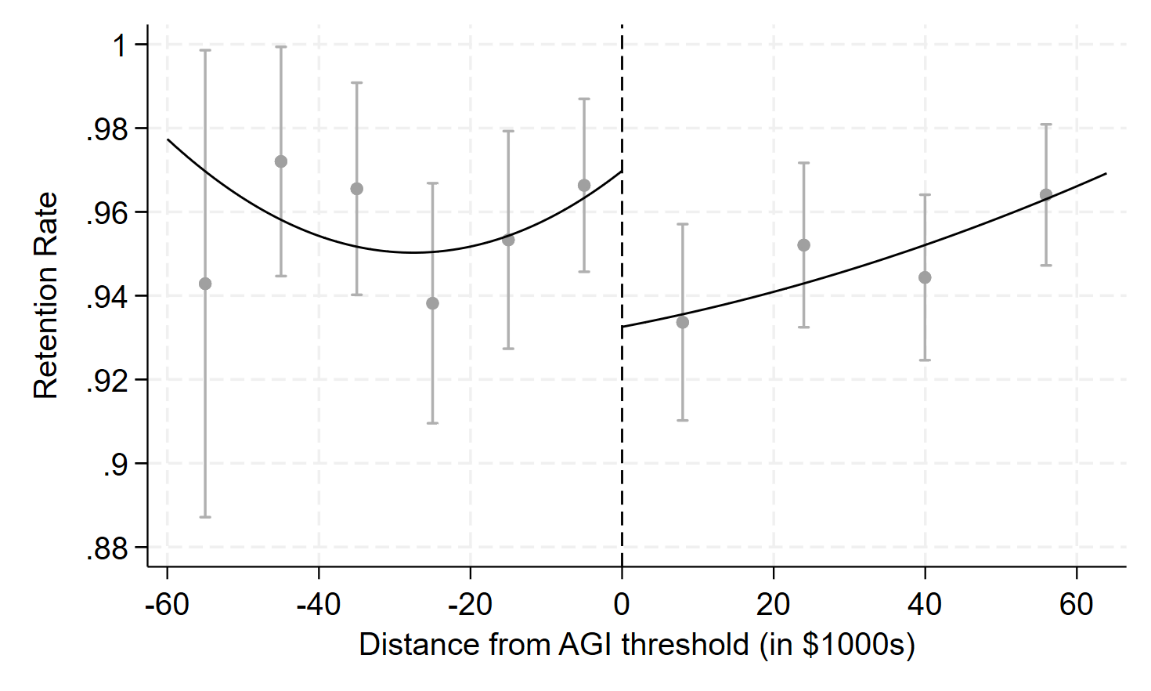

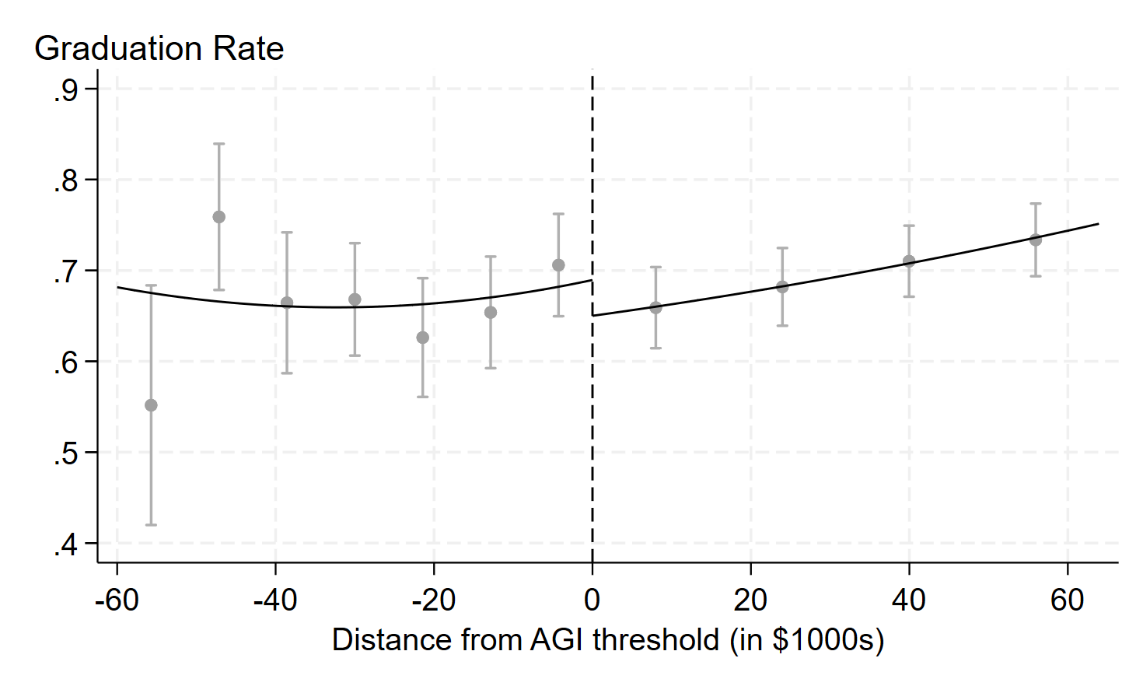

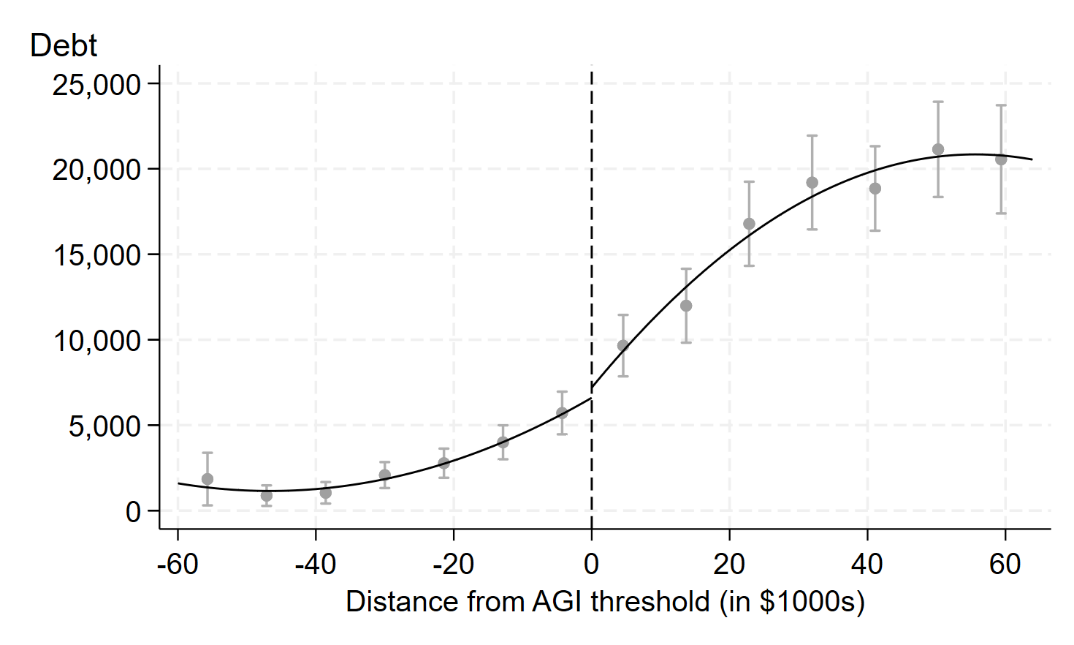

Next, to see if differences in student outcomes are caused by BTP, the analysis compared students on either side of the income eligibility threshold using a regression discontinuity design. Under specific conditions met in this study, students are considered essentially randomly assigned to treatment, so the results can be attributed to BTP rather than other factors. Figure 1 depicts the trend in student outcomes across income levels. A discontinuity, or jump, in the trend line indicates the outcome is different from what would be expected had BTP students not participated in the program.

For students close to the eligibility threshold, results indicate that:

- BTP improves student retention into their second year by about three percentage points.

- BTP has no detectable effect on graduation, but BTP students are graduating at similarly high rates as their non-BTP peers overall.

- BTP may decrease debt. Other sources of financial aid were packaged to avoid a large drop-off in aid for ineligible students, so the trend in debt levels is fairly continuous around the cutoff. Average differences in Table 1 are largely driven by the lowest and highest income students in the sample.

Tuition-free financial aid programs can be designed to support low-income students at selective institutions by awarding aid generously, limiting barriers, and increasing services.

Free college programs like BTP can affect student outcomes through direct cost reduction as well as through messaging and price simplification. Messaging will be most effective when eligibility criteria are easy to understand, like AGI. Criteria based on information campuses already collect, like FAFSA data, eliminate the need for additional applications. Programs guaranteeing continuous aid based on initial eligibility can reduce the barrier of aid loss and help students plan ahead.

The cost of college extends well beyond tuition, and students often need additional support to persist. Following BTP, UW-Madison developed a new program covering full cost of attendance for Pell students.[11] Other efforts connect students to basic needs resources and waive fees for campus activities.[12] Non-financial supports can strengthen student success as well. Many selective institutions have historically enrolled high-income students, and campuses need to assess practices which may hinder belongingness for low-income students.

The cost of tuition-free programs will vary widely across institutions depending on eligibility criteria, tuition costs, and enrollment. At UW-Madison, robust institutional aid meant most low-income students’ tuition was covered prior to launching BTP, reducing the amount needed to fund the new program as a last-dollar design. Institutional leaders estimating the cost of implementing a similar program should consider the gap between tuition costs and average federal, state, and existing institutional aid by income. Institutional leaders should also consider the additional costs of marketing, administration, and student support services.

Table 1: Average Student Characteristics by BTP Status

| Outcomes | BTP participants | Non-participants |

| Continuous Enrollment into Year 2 | 95.8% | 94.9% |

| Graduated Within Four Years | 67.1% | 69.6% |

| Total Debt | $2,930 | $16,872 |

| Number of Students | 1,300 | 1,912 |

Figure 1: Discontinuities in Student Outcomes at the BTP Eligibility Threshold

Panel A: Retention

Panel B: Graduation

Panel C: Debt

Improving First-Year Outcomes for First-Generation Students through Summer Engagement Programs

Insights from the Kessler Scholars Program*

Authors: Ifeatu Oliobi, Kristen Glasener, James Dean Ward, Elizabeth Davidson Pisacreta, Caroline Doglio, and Dillon Ruddell

*The authors of this research were not awarded an ATI Student Success Research Grant, but rather, this research was conducted as part of the Kessler Scholars Program evaluation, which is generously supported by Bloomberg Philanthropies and the Wilpon Family Foundation.

Navigating the Transition from High School to College

The transition from high school to college is an exciting yet challenging period for many students, characterized by new academic expectations and social experiences. Many first-year students struggle with feelings of self-doubt and financial strain and may have difficulty balancing coursework with other responsibilities, all of which can contribute to attrition. First-generation students, in particular, face additional obstacles compared to their peers with college-educated parents. They are often less academically prepared, have fewer financial resources, are more likely to work or care for family members while attending school, and struggle with feeling like they are part of the broader campus community.[13] Compared to their continuing-generation peers, first-generation students are more likely to leave college within their first year, and to leave post-secondary education without earning a credential.[14]

Addressing these challenges through targeted support programs is essential to ensuring that all students—regardless of background—can persist and succeed in higher education. Many colleges and universities offer summer bridge or extended orientation programs that expose newly admitted first-year students to college-level academic work and the campus environment and provide early socialization opportunities before they begin college.[15] Although these programs often vary in length and incorporate a variety of curricular approaches, researchers have found them to yield a variety of benefits for students, including improved academic performance, sense of belonging, self-efficacy, and retention, among others.[16]

Summer Transition Support through the Kessler Scholars Program

The Kessler Scholars Program, a four-year comprehensive support program designed for first-generation limited-income students, is one model that is showing early promise in improving students’ high-school-to-college transition and supporting them to graduation.[17] Through the program, more than 1,000 Kessler Scholars across a national network of 16 institutions supported by the Kessler Scholars Collaborative benefit from financial support, cohort-based engagement, and individualized guidance to help them succeed and thrive at each stage of their college journey.

Incoming first-year Kessler Scholars receive various forms of summer transition support designed to help them cultivate a sense of belonging, improve academic self-efficacy, and navigate the campus environment.[18] Depending on the campus context, existing institutional programs, and students’ needs, these programs take different approaches, including summer bridge programs, orientation programs, or peer mentoring during the summer months. While some institutions design tailored programs exclusively for Kessler Scholars, others leverage existing institution-led programs that target first-generation, limited-income, ethnic/racial minorities, or students who attended under-resourced high schools.

This Study

Using a multiple case study approach, we draw on data from staff interviews, student focus groups, and document review to examine the role that summer transition programs play in shaping incoming, first-year students’ sense of belonging and college preparedness at the 16 colleges and universities that offer the Kessler Scholars Program. We also identify gaps in, or barriers to, participation in these programs and explore the perceived benefits of the program from the perspective of students and staff.

Key Findings

Many first-year scholars arrived on campus with limited awareness of academic success strategies, campus resources, and social connections. These students sought a supportive environment to learn more about the academic expectations of college classes, connect with peers, and navigate a new institution.

“I’m a first-gen [student], so I didn’t know what was expected from going to college and how the classes worked, and I come from a low-income high school. So, I wanted to experience how much work I needed to put it in, and how to become organized.” – Kessler Scholar

Program staff and administrators at participating campuses tailored summer programs to meet the needs of first-generation limited-income students on their campus by 1) intentionally designing programming to help students to succeed both academically and socially at college, and develop a sense of belonging to the institution and the program; 2) proactively anticipating and addressing students’ needs to ensure inclusion and accessibility of programming; and 3) leveraging strategic partnerships with other campus units for program delivery.

“One of our goals was to help [first-year Kessler Scholars] transition positively and build a community to feel more comfortable coming into. That’s certainly, I think, a piece that we were able to meet through this four-day Summer Bridge Program.” – Kessler Scholars Program Staff

Students who attended summer programs say these programs eased their transition to college by fostering a sense of community and connection, enhancing their understanding of campus resources, and improving their academic preparedness. Program staff also observed that students who attended summer programs were more engaged with the program and institution, demonstrated a stronger connection to their cohort, and communicated more frequently with staff once the academic year was underway, compared to non-participants.

“[The summer program] helped me learn about taking classes, doing research, tips and tricks to succeed on campus, and ways to make friends.” – Kessler Scholar

Practical Strategies for Improving the Effectiveness of Summer Transition Programs

- Collaborate with other campus offices offering first-year student supports on the timing and curricular focus of programs to maximize existing resources and reduce content overlap.

- Develop social and interactive programming (e.g., field trips, campus and city tours, group discussions, and hands-on activities) to increase student engagement and foster close connections within cohorts.

- Adequately allocate resources to meet students’ basic needs and attendance costs to increase accessibility.

- Sensitize participating faculty, guest speakers, and campus staff to the unique challenges that first-generation students face and how to use appropriate asset-based framing that highlights students’ strengths and the value they bring to higher education.

- Leverage technology to provide cost-effective virtual support to students who cannot be physically present on campus.

- Consistently gather student input and feedback to identify their needs, any barriers to participation, and feedback on program experiences.

SEEK-ing a Better Future: Supporting College Success for Economically and Educationally Disadvantaged Students

Baruch College

Authors: Isabel Polon, Alex Haralampoudis, and Theodore Joyce

A four-year college degree continues to be the most reliable path to long-term economic security.[19] As the price of college has increased, financial aid opportunities have expanded to ensure that college remains accessible regardless of family income. Yet college completion rates among first-generation college students and students who graduate from low-income high schools or from low-income households still trail behind those of their economically advantaged peers, confirming that financial support alone is not enough to ensure low-income and first-generation college students with non-financial barriers to completion.[20] Research suggests that financial aid is a more effective force for college completion when bundled with non-financial student support services.[21]

In this study, we evaluate the effect of a long-running program that combines financial support with academic advising, career counseling, and tutoring services to promote college completion: the Search for Education, Elevation and Knowledge program, or SEEK. Established at CUNY in 1965, SEEK is a legislatively mandated opportunity program offered at each of CUNY’s senior colleges. SEEK accepts first-year students who would not have been—or who were not—accepted as an incoming freshman at their senior college based on their high school grade point average and/or SAT scores. SEEK provides tutoring, academic and career counseling, and a community of peers. What distinguishes SEEK from the other higher education support programs is that SEEK accepts students with substantially weaker academic preparation than students accepted as part of the regular freshman cohort.

We examine nine cohorts of SEEK students at 11 of CUNY’s bachelor’s degree-granting colleges between 2007 and 2018 (N=11,976) and compare them to all non-SEEK full-time first-time freshmen and Pell Grant recipients at those campuses over the same period (N=52,106). Importantly, SEEK students in our study have average SAT and high school grade point averages (HSGPA) that are almost a full standard deviation lower than their Pell-recipient counterparts. We examine multiple measures of academic success, including credit accumulation, persistence, and graduation adjusted for high school GPA, SAT scores, and a detailed set of fixed effects related to the campus attended, cohort year, race/ethnicity, gender, most desired campus, and county of residence. Results indicate that SEEK students are 3.8 percentage points more likely to be retained after one year (mean, 87 percent), earn 0.23 more credits in the first year (mean, 26.8 credits) and are 4.7 percentage points more likely to graduate in six-years (mean, 63 percent) than their non-SEEK comparison group.

A concern in any observational evaluation is that hard-to-measure characteristics of the participants who choose to enroll in the program and not the services provided by the program account for the positive results. We undertake a number of statistical “stress tests” and the results are the same. For instance, overwhelmingly, the most important predictor of enrollment in SEEK and academic success is a student’s HSGPA. Thus, we contrast SEEK students to their non-SEEK counterparts within each point of HSGPA. We compare, for example, a SEEK student with a HSPGA of 85 (on a scale of 50 to 100) to a non-SEEK student with the same HSGPA adjusted for SAT scores and the panoply of fixed effects listed above. We repeat this exercise for every point of HSGPA from 70 to 90. The average of the 21 coefficients on SEEK are almost identical to the pooled results. Second, we compare the effect of SEEK to the effect of a similar CUNY program that enrolls regular freshmen at the same campus over the same time period but was evaluated by a randomized design. The effect of both programs on five-year graduation rates is substantial and statistically significant relative to the same comparison group.[22] Finally, we apply recent statistical tests for confounding.[23] They show that an unobserved confounder would have to have more explanatory power for both SEEK enrollment and academic outcomes than HSGPA to overturn our results. We can never eliminate the possibility of confounding, but given the explanatory power of HSGPA, we conclude the likelihood of substantial confounding in this context is small.

Results from this study add to the growing literature that financial aid bundled with academic and supportive services can greatly improve outcomes among disadvantaged students. What stands out from the SEEK program is that even if students enter with substantial academic disadvantages, counseling, tutoring, and a supportive community of peers can improve academic outcomes substantively.

Understanding the Use of Basic Needs Services to Better Serve College Students

University of Iowa

Authors: Katharine M. Broton and Solomon Fenton-Miller

Introduction

Substantial shares of college students, and especially those from lower-income families, struggle to meet their daily material needs, hindering their well-being and ability to attain college success. Nationally, one in four undergraduates meet the official definition of food insecure, meaning they have limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods due to financial resource constraints.[24] As a result, colleges and universities are implementing a series of campus-based financial and material supports to help students in immediate need including food pantries, meal vouchers, and emergency aid programs.[25] Moreover, a growing body of scholarship shows that these basic needs services improve academic attainment.[26] Yet, prior research is fragmented and tends to investigate a single service, rather than jointly consider multiple basic needs services on a college campus.

Due to limited resources, colleges and universities often add basic needs services in piecemeal fashion and data tracking systems may be minimal or not fully integrated with campus systems, limiting the ability to consider the full suite of services available on a campus. And even as services have expanded, colleges are either reluctant to advertise due to negative stereotypes about people who are poor or simply lack the capacity.[27] Students often hear about basic needs insecurity services via word-of-mouth as the underlying middle- and upper-class orientation of higher education expects students to be independent and autonomous in seeking solutions to problems they encounter.[28] So, students in financial need must not only overcome a knowledge gap about what campus resources exist, but they must also overcome logistical and psychological barriers (e.g., stigma) to seeking out, accepting, and using known resources. As a result, students who may have a higher need for support may be less likely to seek out and use college resources due to the institution’s organization and practices.[29]

Study Findings

This study investigated how students used the trio of basic needs services available on a large public university campus. In doing so, it shifts the lens from a programmatic perspective to a student-centered examination of how undergraduates navigate available campus basic needs services. Examination of 48,084 students over nine semesters indicates that just one in 10 undergraduates used at least one basic needs service.

Figure 1: Share of Undergraduates Using Any Campus Basic Needs Services

| Used service | 9.5 percent |

| Did not use service | 90.5 percent |

Note: Analysis includes 48,084 students over nine semesters

Among service users, most students used just one service for a single semester, receiving a modest level of support such as one or two visits worth of food from the campus pantry, two packs of meal vouchers worth 14 total meals in the dining hall, or about $500 in emergency grant aid. The meal share program was the most used basic needs service among undergraduates. It may be particularly popular for a few reasons. First is the low barrier to entry: students simply need to complete a short online request form, wait 24-48 hours for it to be processed, and then the meals get loaded onto their university ID card. Then, students simply scan their ID to eat in one of several campus cafeterias or marketplaces across campus—no meal preparation necessary. Next, because the meal support is distributed via students’ university ID card, no one knows that the meals were donated, eliminating stigma. Finally, it is relatively generous, often distributing 14 meals per request. Prior research shows that eating with peers in the dining hall can predict academic success,[30] and meal vouchers, in particular, can improve academic attainment,[31] suggesting that the meal voucher program may not only be appealing to students, but good for institutional retention as well.

Implications for Practice

These findings offer several insights for college and university leaders concerned about the implementation and use of campus basic needs services. Practitioners should not be afraid to advertise services for fear of being overrun by students looking for a free handout.[32] Students were relatively conservative in their service use, receiving only a modest amount of support for a limited amount of time. Rather than treating free services without sufficient respect, it appears that students may not be accessing services that could further support their educational goals. Thus, practitioners should consider increasing proactive outreach and referral systems to better reach students.[33] Additionally, when this university relocated their food pantry to a more prominent central location and included it in the campus visitor walking tour, visibility and usage increased, highlighting the value of having an inviting physical space devoted to basic needs on campus. These implementation approaches can help to reduce barriers to entry and associated stigma and serve as a first step in updating the campus culture. While additional resources are needed to better serve all college students, the ways in which basic needs resources are integrated into campus as routine services should also be of critical consideration.

Endnotes

- David Nguyen, “Low-Income Students Thriving in Postsecondary Educational Environments,” Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 16, no. 4 (2023): 497-507, https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2022-12886-001. ↑

- Ashley Mowreader, “Survey: Half of First-Year Seminars Focus on Academics, Student Success,” Inside Higher Ed, February 26 2024, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/student-success/academic-life/2024/02/26/academic-success-priority-first-year-seminars. ↑

- “An Introduction to Design Thinking Process Guide,” Hasso Plattner Institute of Design at Stanford, accessed April 2 2025, https://web.stanford.edu/~mshanks/MichaelShanks/files/509554.pdf. ↑

- Michael Sparrow, “Students from Low-Income Backgrounds: Characteristics, Common Barriers, and Initiatives to Better Support Student Success,” New York Journal of Student Affairs, under review. ↑

- Christine Harrington, (in-press) ↑

- Michael Sparrow et al.,“Using Focus Groups to Explore the Needs of Students from Low-Income Backgrounds: First-Year Experience Practitioner Perspectives,” Peabody Journal of Education, forthcoming 2025. ↑

- We recommend using the following report to to identify local community colleges: Sunny Chen, Emily Schwartz, Cindy Le, and Elizabeth Davidson Pisacreta, “Right in Your Backyard: Expanding Local Community College Transfer Pathways to High-Graduation-Rate Institutions,” Ithaka S+R, 21 July 2021, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.315695. ↑

- See helpful guide books here: Joshua Wyner, KC Deane, Davis Jenkins, and John Fink, “The Transfer Playbook: Essential Practices for Two-and Four-Year Colleges,” Community College Research Center, The Aspen Institute College Excellence Program, The National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, 2016, https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/transfer-playbook-essential-practices.html;Tania LaViolet, Kathryn Masterson, Alex Anacki, Josh Wyner,John Fink, Aurely Garcia Tulloch, Jessica Steiger, and Davis Jenkins “The Transfer Paybook: A Practical Guide for Achieving Excellence in Transfer and Bachelor’s Attainment for Community College Students, 2nd Ed,” The Aspen Institute College Excellence Program, The Community College Resource Center, March 2025, https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/transfer-playbook-second-edition.pdf. ↑

- Caroline M. Hoxby and Christopher Avery, “The Missing “One-Offs”: The Hidden Supply of High-Achieving, Low Income Students,” National Bureau of Economic Research, 2012, https://doi.org/10.3386/w18586. ↑

- Elise Marifian, “Cost Uncertainty, Financial Aid, and the Enrollment Choices of Low-Income Students,” SSRN Electronic Journal (November 2023) https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4816609. ↑

- “Bucky’s Pell Pathway,” University of Wisconsin-Madison, Office of Student Financial Aid, https://financialaid.wisc.edu/types-of-aid/pell-pathway/. ↑

- “Basic Needs Student Support,” University of Wisconsin-Madison, https://basicneeds.students.wisc.edu/; “The No Fees Project,” University of Wisconsin-Madison, Office of Student Financial Aid, https://financialaid.wisc.edu/services/no-fees-project/. ↑

- Matthew C. Atherton, “Academic Preparedness of First-Generation College Students: Different Perspectives,” Journal of College Student Development 55, no. 8 (2014): 824-829, https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/1/article/561674/pdf; Carmen Tym, Robin McMillion, Sandra Barone, and Jeff Webster, “First-Generation College Students: A Literature Review,” TG (Texas Guaranteed Student Loan Corporation) (2004), https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED542505.pdf; Ernest T. Pascarella, Christopher T. Pierson, Gregory C. Wolniak, and Patrick T. Terenzini, “First-Generation College Students: Additional Evidence on College Experiences and Outcomes,” The Journal of Higher Education 75, no. 3 (2004): 249-284, https://heritage.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Research_Related_to_Success_of_First_Generation.pdf.Michael J. Stebleton, Krista M. Soria, Ronald L. Huesman Jr., “First-Generation Students’ Sense of Belonging, Mental Health, and Use of Counseling Services at Public Research Universities,” Journal of College Counseling 27, no. 1 (April 2014): 6-20, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/j.2161-1882.2014.00044.x; ↑

- Emily Forrest Cataldi, Christopher T. Bennett, and Xianglei Chen, “First-Generation Students: College Access, Persistence, and Postbachelor’s Outcomes. Stats in Brief. NCES 2018-421,” National Center for Education Statistics, 2018, https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018421.pdf; “First Year Experience, Persistence, and Attainment of First-Generation College Students,” NASPA, 2019, https://firstgen.naspa.org/files/dmfile/FactSheet-02.pdf. ↑

- Adrianna Kezar, “Summer Bridge Programs: Supporting All Students,” ERIC Digest, 2000, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED442421.pdf ↑

- Beverlyn Grace-Odeleye and Jessica Santiago, “A Review of Some Diverse Models of Summer Bridge Programs for First-Generation and At-Risk College Students,” Administrative Issues Journal: Connecting Education, Practice, and Research 9, no. 1 (2019): 35-47, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1221221. ↑

- Ifeatu Oliobi, Caroline Doglio, and Dillon Ruddell, “Evaluating the Kessler Scholars Program: Findings from the Academic Year 2022-23,” Ithaka S+R, 11 July 2024, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.320987. ↑

- Ifeatu Oliobi, Dillon Ruddell, and Caroline Doglio, “Tailored Support for First-Year, First-Generation College Students: Findings from an Evaluation of the Kessler Scholars Program,” Ithaka S+R, 19 December 2024, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.321866. ↑

- Liang Zhang, Xiangmin Liu, and Yitong Hu, “Degrees of Return: Estimating Internal Rates of Return for College Majors Using Quantile Regression,” American Educational Research Journal 61, no. 3 (March 2024): 577-609, https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312241231512. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Richard Fry, “First-Generation College Graduates Lag Behind Their Peers on Key Economic Outcomes,” The Pew Research Center, May 18 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2021/05/18/first-generation-college-graduates-lag-behind-their-peers-on-key-economic-outcomes; Margaret Cahalan, Nicole Brunt, Terry Vaughan III, Erick Montenegro, Stephanie Breen, Esosa Ruffin, and Laura Perna, “Indicators of Higher Education Equity in the United States 2024: 50-Year Historical Trend Report,” The Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education, Council for Opportunity in Education (COE) and Alliance for Higher Education and Democracy of the University of Pennsylvania (Penn AHEAD), 2024, https://www.pellinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/PELL_2024_Indicators-Report_f.pdf; Lindsay C. Page, Stacy S. Kehoe, Benjamin L. Castleman, and Gumilang Aryo Sahadewo, “More than Dollars for Scholars: The Impact of the Dell Scholars Program on College Access, Persistence, and Degree Attainment,” Journal of Human Resources 54, no. 3 (July 2019): 683-725, https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.54.3.0516.7935R1; Rodney J. Andrews, Scott A. Imberman, Michael F. Lovenheim, “Recruiting and Supporting Low-Income, High-Achieving Students at Flagship Universities,” Economics of Education Review 74 (February 2020): 101923, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2019.101923;Charles T. Clotfelter, Steven W. Hemelt, and Helen F. Ladd, “Multifaceted Aid for Low-income Students and College Outcomes: Evidence from North Carolina,” Economic Inquiry 56, no. 1 (August 2017): 278–303, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.12486;Michael Weiss, Alyssa Ratledge, Colleen Sommo, and Himani Gupta, “Supporting Community College Students from Start to Degree Completion: Long-Term Evidence from a Randomized Trial of CUNY’s ASAP,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 11, no. 3 (July 2019): 253–297, https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20170430. ↑

- Diana Stumbos, Zineta Kolennovic, Himani Gupta, “Accelerate, Complete, Engage (ACE): Outcomes for Three First-Time Freshman Cohorts. City University of New York,” CUNY Accelerated Study in Associate Programs and Accelerate, Complete, Engage, August 2022, https://www1.cuny.edu/sites/asap/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2022/09/CUNY_ACE_Research_Brief_August-22_Web-Final.pdf; Michael Scuello and Diana Strumbos, “Evaluation of Accelerate, Complete, Engage (ACE) at CUNY John Jay College of Criminal Justice,” CUNY Accelerated Study in Associate Programs; Accelerate, Complete, Engage; metis associates, March 2024, https://www.cuny.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/page-assets/about/administration/offices/student-success-initiatives/asap/about/ace/300414_CUNY_March_2024_ACE_Final_Report_m1-1.pdf. ↑

- Peng Ding, Tyler J. VanderWeele, “Sensitivity Analysis Without Assumptions,” Epidemiology 27, no. 3 (May 2018), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26841057/. ↑

- “National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS),” National Center for Education Statistics, US Department of Education, https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/npsas/;Gary Bickel, Mark Nord, Cristofer Price, William Hamilton, and John Cook, “Guide to Measuring Household Food Security, Revised 2000,” US Department of Agriculture (USDA), Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Analysis, Nutrition, and Evaluation, March 2000, https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/FSGuide.pdf. ↑

- Katherine Speirs, Stephanie Grutzmacher, Ashley Munger, and Timothy Ottusch, “How Do US Colleges and Universities Help Students Address Basic Needs? A National Inventory of Resources for Food and Housing Insecurity,” Educational Researcher 52, no 1 (December 2022): 16-28, https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X221139292. ↑

- Katharine Broton, Milad Mohebali, and Sara Goldrick-Rab, “Meal Vouchers Matter for Academic Attainment: A Community College Field Experiment,” Educational Researcher 52, no. 3 (February 2023): 155-163, https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X231153131;Bradley Curs, Casandra Harper, and Sangmin Park, “The Role of Emergency Financial Relief Funding in Improving Low-Income Students’ Academic and Financial Outcomes Across Demographic Characteristics,” EdWorkingPaper, July 2024, https://doi.org/10.26300/wgyh-ek62; Sydney Schreiner Wertz, “On-Campus Food Pantries and Educational Attainment: Evidence from Ohio,” (presentation, APPAM Fall Research Conference, November 2022). ↑

- Katharine M. Broton, Graham N.S. Miller, and Sara Goldrick-Rab, “College on the Margins: Higher Education Professionals’ Perspectives on Campus Basic Needs Insecurity,” Teachers College Record 122, no. 3 (March 2020): 1-32, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/016146812012200307; Katharine Broton, Milad Mohebali, and Sara Goldrick-Rab, “Deconstructing Assumptions about College Students with Basic Needs Insecurity: Insights from a Meal Voucher Program,” Journal of College Student Development 63, no. 2 (2022): 229-234, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1352226; Christian Geckeler, Carrie Bach, Michael Pih, and Leo Yan, “Helping Community College Students Cope with Financial Emergencies: Lessons from the Dreamkeepers and Angel Fund Emergency Financial Aid Program,”. MDRC, May 2008, https://mdrc.org/sites/default/files/full_383.pdf; Rebecca L. Hagedorn-Hatfield et al., “Campus‐based Programmes to Address Food Insecurity Vary in Leadership, Funding and Evaluation Strategies,” Nutrition Bulletin 47, no. 3 (September 2022): 322-332, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36045103/; Michael Katz, The Undeserving Poor: From the War on Poverty to the War on Welfare, (Pantheon Books, 1990). ↑

- Alexis Wesaw, Kevin Kruger, Amelia Parnell, “Landscape Analysis of Emergency Aid Programs,” National Association of Student Personnel Administrators, 2016 https://www.naspa.org/report/landscape-analysis-of-emergency-aid-programs; Janet Chang, Shu-wen Wang, Colin Mancini, Brianna McGrath-Mahrer, and Sujey Orama de Jesus, “The Complexity of Cultural Mismatch in Higher Education: Norms Affecting First-Generation College Students’ Coping and Help-Seeking Behaviors,” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 26, no. 3 (2020), 280; Nicole M. Stephens, Stephanie A. Fryberg, Hazel Rose Markus, Camille S. Johnson, “Unseen Disadvantage: How American Universities’ Focus on Independence Undermines the Academic Performance of First-Generation College Students,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 102 (2012); 1178-1197, http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0027143. ↑

- Ernest T. Pascarella, Christopher T. Pierson, Gregory C. Wolniak, and Patrick T. Terenzini, “First-Generation College Students: Additional Evidence on College Experiences and Outcomes,” The Journal of Higher Education 75 (October 2016): 249 –284, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2004.11772256; Michael J. Stebleton, Krista M. Soria, Ronald L. Huesman Jr., “First-Generation Students’ Sense of Belonging, Mental Health, and Use of Counseling Services at Public Research Universities,” Journal of College Counseling 17, no. 1 (April 2014): 6-20, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/j.2161-1882.2014.00044.x; Nicole M. Stephens, Hazel Rose Markus, and L. Taylor Phillips, “Social Class Culture Cycles: How Three Gateway Contexts Shape Selves and Fuel Inequality,” Annual Review of Psychology 65 (January 2014): 611-634, https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115143. ↑

- Nicholas Bowman, Lindsay Jarratt, Linnea Polgreen, Thomas Kruckeberg, and Alberto M. Serge, “Early Identification of Students’ Social Networks: Predicting College Retention and Graduation via Campus Dining,” Journal of College Student Development 60, no. 5 (2019): 617–622, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1232885. ↑

- Katharine M. Broton, Milad Mohebali, and Sara Goldrick-Rab, “Meal Vouchers Matter for Academic Attainment: A Community College Field Experiment,” Educational Researcher 52, no. 3 (February 2023): 155-163, https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X231153131. ↑

- Christian Geckeler, Carrie Beach, Michael Pih, and Leo Yan, “Helping Community College Students Cope with Financial Emergencies: Lessons from the Dreamkeepers and Angel Fund Emergency Financial Aid Programs,” MDRC, May 2008, https://mdrc.org/sites/default/files/full_383.pdf ↑

- Sara Goldrick-Rab, Christine Baker-Smith, Eric Bettinger, Gregory Walton, Shannon Brady, Japbir Gill, and Elizabeth Looker, “Connecting Community College Students to Non-Tuition Supports During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice, February 2022,https://www.luminafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/non-tuition-supports.pdf; Jessica Lasky-Fink, Jessica Li, et al., “Reminder Postcards and Simpler Emails Encouraged More College Students to Apply for CalFresh,” California Policy Lab with The People Lab, 18 August 2022, https://www.capolicylab.org/outreach-to-california-college-students-encouraged-them-to-apply-for-calfresh/; “Use of FAFSA Data to Administer Federal Programs,” US Department of Education, January 20 2022, https://fsapartners.ed.gov/knowledge-center/library/dear-colleague-letters/2022-01-20/use-fafsa-data-administer-federal-programs. ↑