AI and the Research Enterprise at Emerging Research Institutions

Insights from the First GRANTED Workshop at Montclair State University

Over the course of 2025, the research enterprise in the United States has become unusually visible. Funding cuts and new federal mandates have brought sweeping changes, drawing public attention to a system that operates out of the public eye, even as it produces transformative knowledge and innovations for society. Much of the conversation has focused on the impact on researchers themselves, their livelihoods, their ability to advance science, as well as on the existential impact of changes on the field of higher education.

Less visible, however, are the research administrators whose work makes the enterprise function and whose jobs require deep understanding of institutional and federal funding policies. Working across a number of campus units, these administrators facilitate the flow of funding that sustains scientific and humanistic discovery by keeping abreast of funding patterns, identifying funding opportunities, processing grants, and ensuring compliance.

As federal grant policies and priorities have rapidly shifted, the work for research administrators has grown more complex. Keeping up with changing regulations, many of which deviated substantially from policies issued only a year earlier, is a daunting task. At the same time, the emergence of generative AI tools has enabled the automation of routine and repetitive tasks, and one funding agency has speculated that this has led to an increase in proposal submissions.[1] Meanwhile, many universities lost staff to retirement during the COVID-19 pandemic leaving research administrators with more to manage and fewer colleagues to share the load.

For emerging research institutions (ERIs), these challenges are especially acute. Larger, better-resourced universities may be able to absorb the costs of updating infrastructure, expanding staff capacity, and training faculty and student researchers. ERIs, already operating with lean resources, need to understand how they can strategically adapt.

Within this context, we convened the first of two workshops as part of an NSF-funded project Advancing AI Implementation at Emerging Research Institutions, a project collaboratively led by Ithaka S+R, Montclair State University, and Chapman University. The first workshop was held on Friday, September 12, at Montclair State University and brought together 31 participants from 13 academic and medical institutions in the New York/New Jersey/Pennsylvania region, as well as from an electronic research administration system provider to ask: how can research administrators at ERIs leverage AI to build more sustainable and equitable research capacity?

The day began with a welcome from Stefanie Brachfeld, vice provost for research at Montclair State University, and Martina Nieswandt, vice president for research and graduate education at Chapman University, who framed the goals of the convening. Their remarks were followed by a panel discussion featuring Libby Barak (Montclair State University), Kevin Cooke (APLU), Eric Hetherington (New Jersey Institute of Technology), andTodd Slawsky (Rutgers University), moderated by Stefanie Brachfeld. The panel explored the role of AI in the research enterprise, and panelists addressed key issues such as governance, equity, and competitiveness, from different professional perspectives. Setting the stage for the small group discussions that followed, they shared experiences piloting AI initiatives and discussed the myriad opportunities, risks, and questions AI has introduced into the field.

Among the topics discussed on the panel were rising operational and compliance costs amid shrinking budgets; concern that AI is currently best suited to entry-level tasks, prompting questions about how to train a workforce without foundational experience; the risk that hesitation to engage with AI could exacerbate inequities; trust and transparency as non-negotiables in training and adoption and the need for adaptive AI tools that respect user privacy; the increasing energy costs of running AI infrastructure; and the consensus that AI should support, but not replace, human decision-making in research administration.

After the panel discussion, we moved to the first of three breakout sessions. This session asked participants to assess their institution’s current capacity and needs for supporting researchers and growing their research profile amid the explosion of AI tools and use across higher education. Self-selecting into tables on research administration, AI governance, or research support and development, attendees quickly articulated a long list of shared challenges that limit their availability to support researchers: outdated facilities and infrastructure, fragmented inter-unit collaboration, the difficulty of keeping pace with compliance requirements, lean staffing, uneven cultural acceptance of AI, and lack of AI literacy across campus, but especially among research administrators.

Many of the challenges we heard in this breakout session are overlapping and compounding. For example, research offices often lack in-house expertise in AI, and ongoing staff training has been ad hoc or non-existent. As a result, many participants have turned to professional organizations for guidance. Yet the absence of coherent and consistent training has led to uneven adoption and expertise across staff and campus units. At the same time, researchers are increasingly looking to research administrators for advice on how to use AI responsibly in both their research and grant reporting. Attendees described feeling ill equipped to provide such support, explaining that their heavy workloads leave little time to keep up with the ethical, technical, and legal issues surrounding AI. There is, they emphasized, a strong appetite to understand and leverage AI in their work, but little opportunity to truly learn how to do so. And without a baseline understanding of what AI tools can and cannot do, legally and technically, participants worried about misuse, inefficiency, and inequitable outcomes.

Some participants highlighted very specific gaps in capacity. Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), for example, need training to evaluate how AI is used in human subjects research. Others described how the continued growth of compliance requirements, combined with fewer resources to meet them, has left their offices feeling “underwater.” Several also worried that junior research administrators were not receiving consistent training. Because research administration work involves a high degree of nuance, especially in tasks like redlining contracts and aligning institutional policies with shifting federal requirements, participants expressed concern that promises of AI efficiency might short-circuit the hands-on learning that junior staff need to develop real expertise in the work of supporting and enabling the research enterprise.

The afternoon breakout sessions shifted toward experiments, strategic problem solving, and “pie in the sky” brainstorming centered around three themes that rose to the top in the first breakout session: lack of AI literacy, outdated facilities and infrastructure, and staff capacity and cultural resistance. We asked participants at each table to describe any successes or failures their institution has had to date in experimenting with AI to address these challenges. Some mentioned their institution had piloted modest uses of AI, such as classifying grants or drafting proposal templates. Others had tried embedding AI into compliance training or setting up campus hubs for experimentation. Still, these efforts were mostly ad hoc and unevenly distributed, and many participants said their institutions had not yet attempted anything at a systemic level.

During the conversation, participants also focused on the cultural dimensions of AI adoption. They agreed that building trust, in AI systems, in their own use of them, and with faculty, is essential to successfully integrating AI into research administration workflows. To build trust with faculty, participants emphasized the need to reassure faculty, many of whom encounter AI primarily through students using it in a way that faculty consider to be unethical, that their original ideas and unpublished data will not be released to public and unsupervised AI tools, nor will these tools jeopardize their chances of securing a grant. They would also need to demonstrate that AI can complement, rather than undermine, existing human expertise. However, participants expressed concern about the opacity of many AI platforms, particularly the possibility of backdoor data access that could compromise faculty privacy. This tension underscored a central issue: to build trust with faculty, administrators must first be able to trust the tools themselves, and be trained how to use them responsibly.

To build trust with faculty, administrators must first be able to trust the tools themselves, and be trained how to use them responsibly.

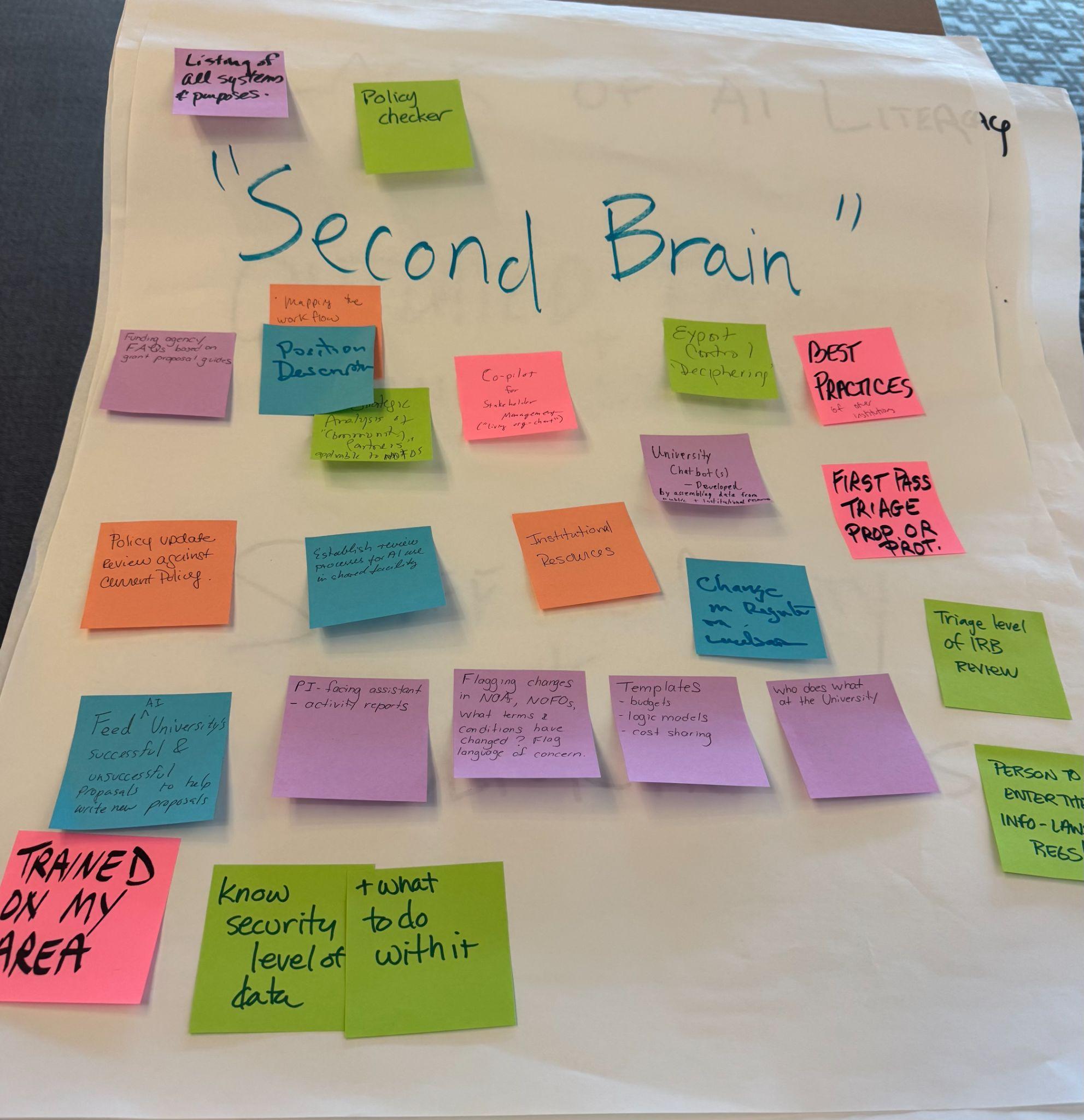

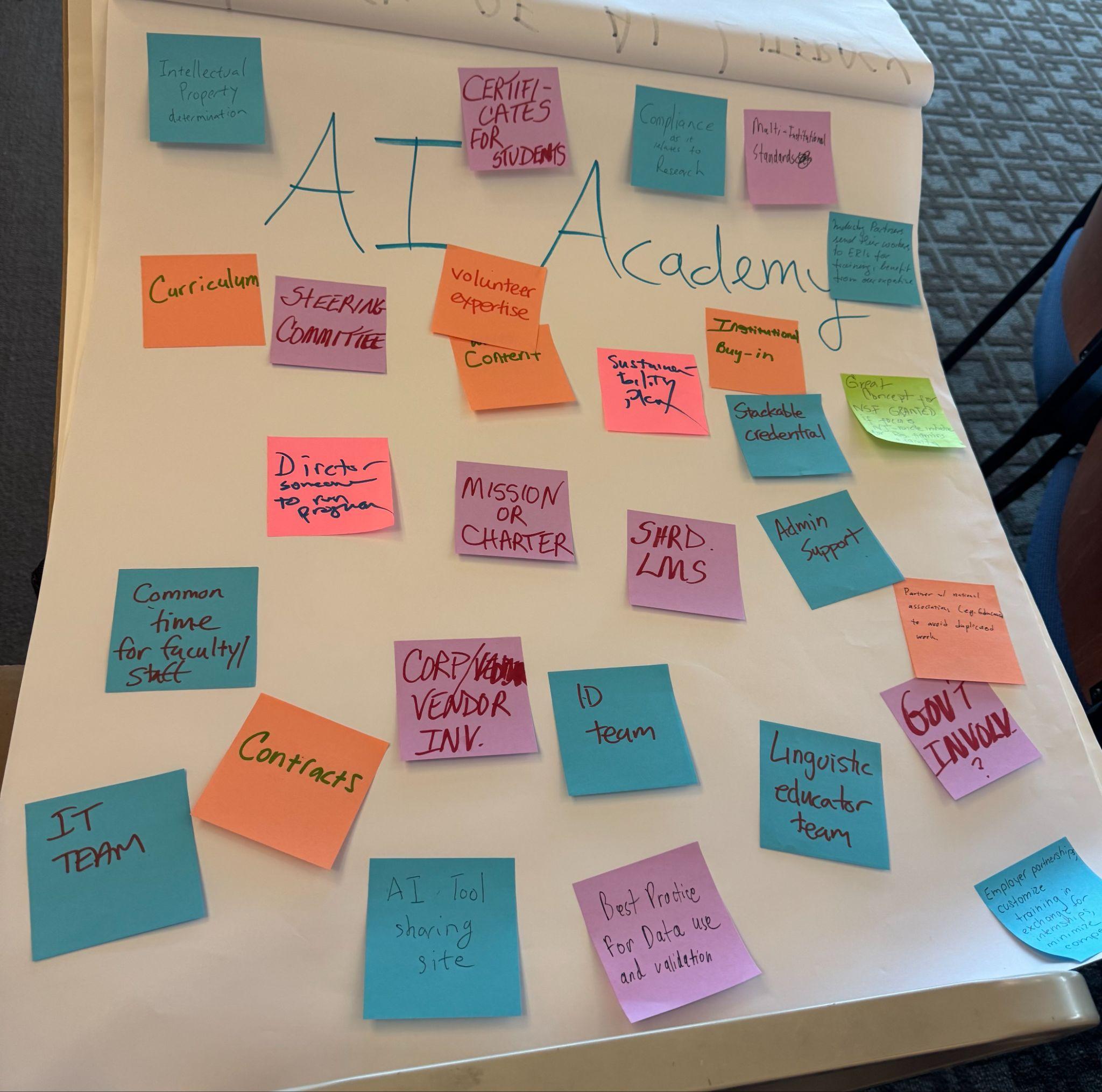

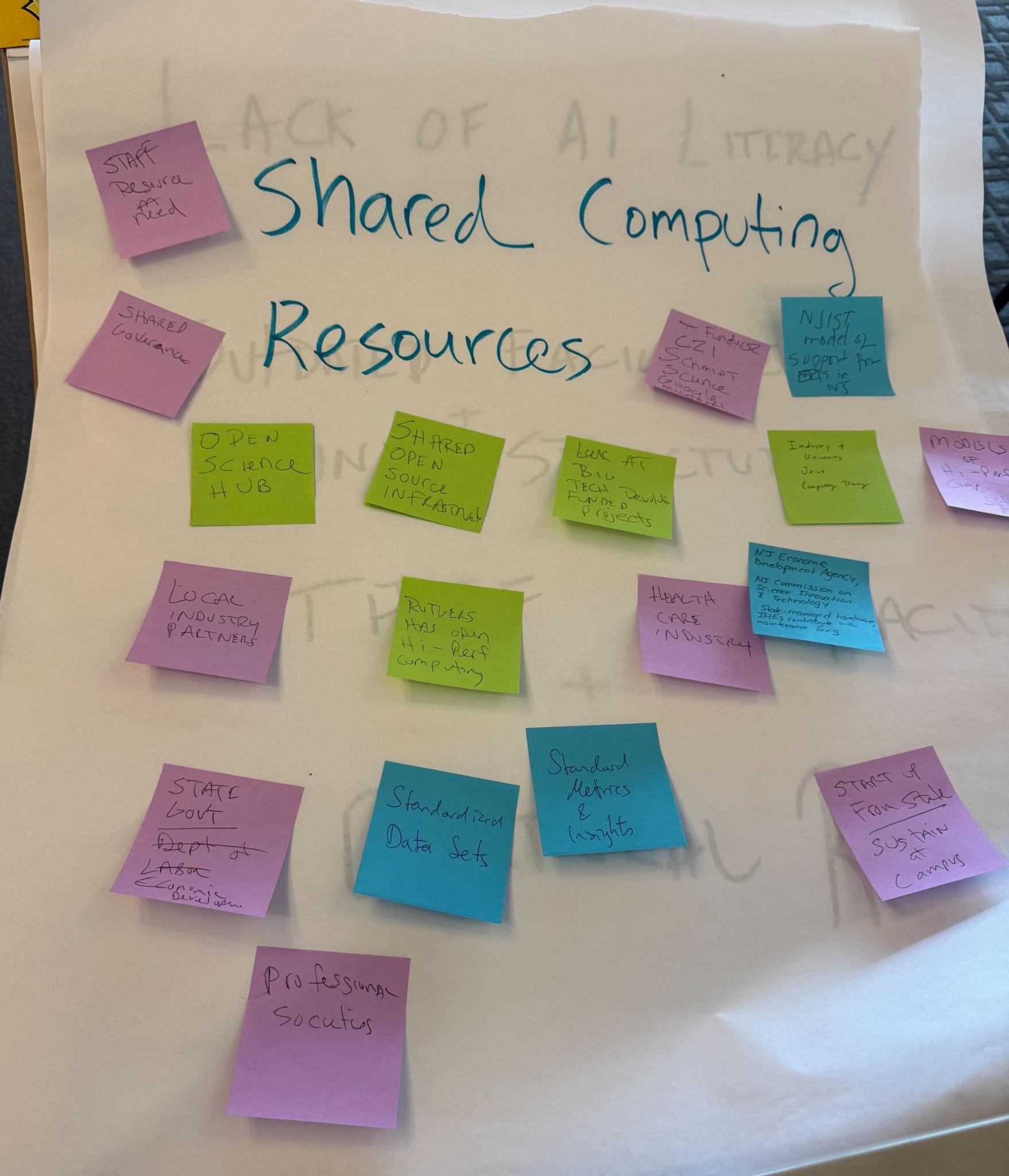

As we turned toward brainstorming possible solutions to the three barriers identified in breakout session one (lack of AI literacy, outdated infrastructure, and staff capacity and cultural resistance), participants shared a number of creative ideas. Among them were portable AI literacy certifications; regional high-performance computing consortia; a research administration AI assistant, a “second brain,” that stays up to date on all federal and institutional policy changes; shared repositories of AI use cases; an “AI Academy” developed in collaboration with regional ERIs; and campus commons where staff, researchers, and students could experiment together. No single idea offered a complete solution, but the collective sense was that ERIs would be strongest if they pursued these challenges collaboratively.

Focusing on the ideas of the “Second Brain,” “AI Academy,” and “Shared Computing Resources,” we used the final breakout session as an “implementation lightning round.” Participants were asked to rapidly generate ideas for what would be needed to turn these proposals into reality:

Throughout the day, much of the conversation centered on understanding what questions to ask and how to sort through both the hype surrounding AI and the fear of “falling behind” when deciding how to implement AI in the work of research administration. Indeed, for many in attendance, the challenge wasn’t about adopting the latest tools quickly, but about discerning what “doing AI right” would look like within their own institutional contexts, even if that meant proceeding more slowly. Many were excited about the possibilities of AI4RA, an NSF-funded project in development at the University of Idaho that aims to develop open-source data models and workflows, and to create trustworthy AI-powered tools specifically for use in research administration at institutions of various sizes.

The workshop concluded with closing reflections from the panelists and a shared sense that collaboration among ERIs will be essential to navigate this complex landscape. The event affirmed the value of gathering across campuses to share experiences and ideas, and imagine new models for research support. Our next workshop, to be held at Chapman University later this year, will build on what we learned at Montclair. There, we will revisit the ideas raised in this first convening and begin to prioritize which are most promising for cross-institutional collaboration and future grant proposals.

For more information about the project please contact: Ruby MacDougall at Ruby.MacDougall@ithaka.org

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant. No. 2437518. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant. No. 2437518. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

- In response to concerns about authorship and originality, the NIH recently issued guidance stating that proposals developed by AI “…are not considered the original ideas of applicants and will not be considered by NIH.” See: https://grants.nih.gov/news-events/nih-extramural-nexus-news/2025/07/apply-responsibly-policy-on-ai-use-in-nih-research-applications-and-limiting-submissions-per-pi. ↑