From Concept to Campus

Lessons from the Design, Launch, and Growth of Transfer Explorer

Introduction

Every year, millions of students set out to continue their education at a new college or university—often carrying with them a transcript full of hard-earned credits. For too many, the move does not go as planned. Credits vanish in the transfer, degree timelines stretch, and the financial and personal costs mount. These problems are not new, and they are not rare. They are the predictable result of a transfer system that is fragmented, opaque, and difficult to navigate without insider knowledge. Transfer Explorer, an online credit mobility tool, was created to confront this challenge by making credit transfer information transparent, accessible, and actionable for students, advisors, and institutions alike.[1] This report tells the story behind the tool—charting its design, pilot, launch, and ongoing improvements—to illuminate the decisions, and partnerships that made it possible and to highlight how Transfer Explorer may be leveraged in the future to improve credit mobility policies and procedures across the country. In doing so, the report is less about the outcomes of Transfer Explorer itself and more on the processes that shaped it.

What is the transfer and credit mobility problem?

For many students, especially those starting at community colleges, the path to a bachelor’s degree is far more difficult than it should be. Community colleges enroll about one-third of US college students, 80 percent of whom aspire to earn a bachelor’s degree.[2] Yet only 16 percent do so within six years.[3] Students who transfer all credits are significantly more likely to graduate (82 percent) than those who lose credits (42 percent),[4] but some studies have found that only about half achieve full credit transfer.[5] In a recent study by Public Agenda, nearly two-thirds of respondents who tried to transfer credit reported at least one negative experience; 58 percent lost credits, and nearly one-quarter found that few or none of their credits transferred.[6]

For many students, especially those starting at community colleges, the path to a bachelor’s degree is far more difficult than it should be.

Unintentional credit loss—caused by curricular misalignment, inconsistent advising, misinformation, or opaque policies—erodes the financial advantage of starting at a lower-cost institution, extends time-to-degree, and disproportionately affects students of color and those from low-income backgrounds.[7]

Articulation agreements are one way institutions and systems have sought to formalize transfer pathways, but they show mixed results. While efforts such as Ohio’s Transfer Module can improve outcomes,[8] statewide policies alone do not guarantee better transfer rates.[9] Many agreements exclude technical fields,[10] fail to reflect evolving student goals,[11] or are difficult to maintain.[12] Moreover, articulation agreements have a limited scope; they are only useful for students who are transferring within certain majors and are transferring to the specific institutions or systems their sending institution has a relationship with.

Credit mobility policies can and should be streamlined to facilitate a smoother transfer experience for students, but research suggests that simply providing clear and accessible credit transfer information can improve students’ course-taking and transfer behavior.[13] Without such transparency, the transfer process remains a complex, often inequitable maze—costing students time, money, and opportunity.

What is Transfer Explorer?

Transfer Explorer is a publicly accessible tool designed to show how prior learning experiences will count toward academic requirements at a destination or receiving college. By making the rules on credit transfer and degree applicability more transparent, the tool allows students and advisers to make better-informed transfer plans and enables institutions to align their programs and course equivalency rules to better facilitate transfer. It also reduces the burden on students and staff to locate and interpret relevant information that often exists across disparate sources. Transfer Explorer is operated by ITHAKA, a nonprofit organization whose mission is to broaden access to quality postsecondary education and improve student outcomes.[14]

Transfer Explorer home page, as seen on mobile and desktop.

As of Fall 2025, the platform contains more than one million course equivalency rules across 14 destination institutions in the live version accessible to the public. Through coordination with the Connecticut State Colleges and Universities (CSCU), the South Carolina Commission on Higher Education (SC CHE), the Washington Student Achievement Council (WSAC), and the City University of New York (CUNY), a total of 45 institutions in four states are currently participating in the project, with the participation of additional institutions coming soon. The beta version of Transfer Explorer launched with its first three institutions in February 2025, followed by an additional four institutions in Summer 2025. At the time of this writing in Fall 2025, a total of 14 institutions have given their approval to launch on Transfer Explorer.

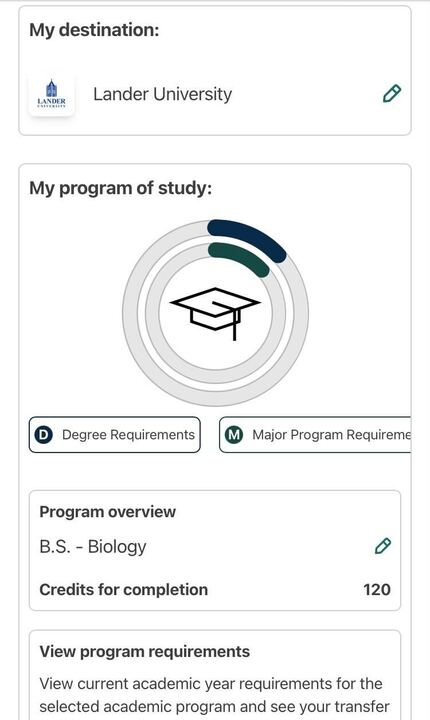

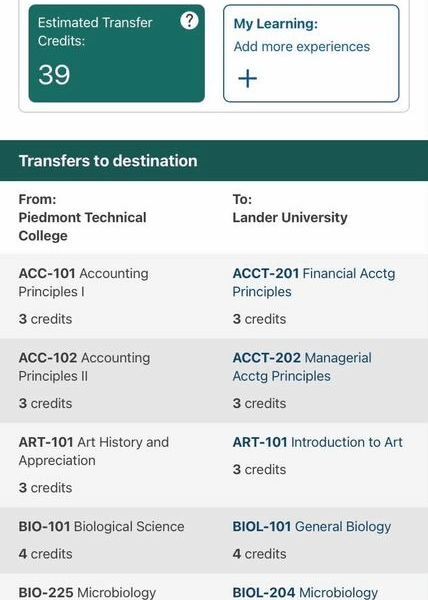

In its current beta version, Transfer Explorer already enables learners to take several concrete steps in planning their transfer journeys. Users can record the courses they have already taken—or plan to take—at any college or university, explore how those courses transfer and apply to degree requirements at another school, create additional explorations to compare transfer outcomes across multiple institutions and degrees, save and share these explorations through a personal link or direct email to participating schools, and discover background information about Transfer Explorer member institutions.

Transfer Explorer results page showing degree progress (left) and equivalencies (right).

The tool was inspired by and builds on the work of CUNY Transfer Explorer (CUNY T-Rex), which was launched in 2020 to help students and advisors within the CUNY system navigate how credits transfer among CUNY institutions. CUNY T-Rex, a publicly accessible credit transfer platform, was developed by the City University of New York in collaboration with Ithaka S+R. Officially launched in 2020, the tool grew out of a prototype created at Queens College by Christopher Vickery, and was expanded through Ithaka S+R’s Articulation of Credit Transfer (ACT) project, with support from philanthropic funders and strong leadership at CUNY. T-Rex provides students, advisors, and faculty with real-time information being automatically and continuously updated on course equivalencies, prior learning credits, and degree requirements across CUNY’s 20 undergraduate colleges, making visible how credits transfer and apply to specific programs of study. Its success has been attributed to a combination of centralized, up-to-date, systemwide data, user-centered design, and committed champions who bridged technical and policy expertise.[15]

To create the national version of Transfer Explorer, ITHAKA compiled a team that currently includes software engineers, a user experience designer, project managers, and strategists. The contributions of staff and leadership at the nonprofit DXtera Institute, which processes data from institution student information systems and provides access via their CampusAPI Requisite and Equivalency services,[16] has also been integral to the project. State and system leads, our main points of contact in each participating state, have acted as liaisons to coordinate institutional participation. The development and launch of Transfer Explorer have been made possible through the philanthropic support of six foundations.

The goals of Transfer Explorer are to improve transfer outcomes and make transfer data more visible and transparent. By aggregating credit mobility information in one central, user-friendly place, the tool aims to help prospective transfer students complete their studies with less time, cost, and wasted effort, while supporting institutions in proactively improving the transfer experience.

This report

While much research on transfer tools focuses on their usage and impact, less is known about what it takes to design, build, and launch them, particularly across multiple states, systems, and institutions. Documenting this process is important because it surfaces the technical, organizational, and policy complexities that can determine whether a tool is implementable at scale. Additionally, documenting this process provides other states and institutions with a realistic picture of the time, resources, and collaboration required to integrate their data into the tool and publicly launch. Finally, these insights provide value by highlighting the role of negotiation, iteration, and relationship-building in producing a tool that is not only functional but trusted by its users.

This report documents the processes involved in developing Transfer Explorer. Specifically, it seeks to answer the following questions:

- What processes have been involved in designing, piloting, and launching Transfer Explorer?

- How has Transfer Explorer been adapted to accommodate varying system and institutional configurations and policy contexts?

- What are the intended goals and audiences of Transfer Explorer, as perceived by those involved in its design and launch?

- How can Transfer Explorer be improved and expanded to better support student transfer?

After the methods section, which describes our data sources, participants, and analytic approach, we present findings organized by the three workstreams that comprise the development of Transfer Explorer:

- Designing – how the concept for Transfer Explorer was shaped, including decisions about purpose, audience, and technical integration.

- Onboarding – the early stages of work with initial participating institutions and states, lessons learned from testing in real-world conditions, and the transition from the initial phase to public availability, including varying institutional approaches and readiness levels.

- Improving – how user feedback, testing, and ongoing collaboration have informed refinements to the tool.

These categories should not be understood as distinct phases, but as overlapping and recurring modes of work that continue to inform one another. We then discuss potential directions for future development, followed by a discussion and conclusion section that reflects on the process as a whole, highlights lessons learned, and considers the implications for transfer policy and practice.

Methods

This report draws on desk research and semi-structured interviews with individuals directly involved in the development and implementation of Transfer Explorer. Our desk research included a review of meeting agendas, public announcements, and other relevant documents to provide context and inform the interview process.

We conducted nine interviews with members of the internal ITHAKA product team, external developers (including contributors to CUNY T-Rex), and state agency partners serving as primary project contacts.[17] While not exhaustive, this group represented a cross-section of perspectives on product design, technical integration, and state- or system-level coordination.

Interviews were approximately 60 minutes each, conducted via Webex, and recorded with consent. The interview protocols (see Appendix B) were loosely structured so they could be tailored to each participant’s role. Transcripts were generated using Otter.ai and thematically coded in Dedoose. One interview was used for coder calibration before all three authors collaborated to code and analyze the remaining transcripts.

Findings: the process of developing Transfer Explorer

The national version of Transfer Explorer was not built in a vacuum. It emerged from a complex and iterative process that unfolded across multiple institutions, states, and teams—each bringing their own perspectives, constraints, and goals. The process has never followed a straight line; instead, progress in one area often informed and reshaped work in another, demonstrating the recursive and interdependent nature of building such a tool. While the tool may now appear to users as a relatively straightforward user-friendly website for exploring how credits transfer and apply across colleges and universities, its development required navigating a layered set of design decisions, technical challenges, and institutional relationships.

The process of building Transfer Explorer has so far spanned nearly three years and involved a wide range of collaborators (see Appendix A for a high-level timeline). This included multiple divisions within ITHAKA, a nonprofit organization whose mission is to improve access to knowledge and education for people around the world. At the core of ITHAKA’s involvement was the product and engineering team housed within JSTOR Labs, who led the technical development and user interface design. Labs is the innovation arm of ITHAKA, created to experiment with new technologies and design approaches that advance access to knowledge and improve higher education. This team worked in close partnership with researchers and project leads from Ithaka S+R, who provided strategic guidance, coordinated with funders and participating states and institutions, and helped define the tool’s goals and research agenda. Ithaka S+R, the research and strategic consulting division of ITHAKA, provides research and strategic guidance to help the academic and cultural communities serve the public good and navigate economic, demographic, and technological change. DXtera, a nonprofit technology organization with expertise in data integration and system interoperability, played a critical role by providing key technical infrastructure allowing Transfer Explorer to connect with diverse student information systems. Also central to the project were state, system, and institution-level partners whose staff facilitated institutional participation, helped onboard local teams, and served as crucial intermediaries between the core team and institutional staff.

Transfer Explorer itself was inspired by the earlier development of CUNY T-Rex, a tool built for the CUNY system to allow users to see how courses transfer across CUNY campuses. Several team members who helped build CUNY T-Rex have been involved in the national version of Transfer Explorer as well, and the lessons learned from CUNY T-Rex served as a jumping-off point for the development of Transfer Explorer. CUNY T-Rex served as a proof of concept, a kind of first complete draft helping the project team to understand what has to be done and how. But expanding from a single citywide system to a multi-state, multi-institutional tool introduced a new level of complexity requiring new technical solutions and a fundamentally collaborative and adaptive development process to unify and normalize data across multiple source systems.

To better understand how Transfer Explorer was conceived, tested, launched, and refined, we spoke with a cross-section of those involved in its creation. Through these interviews, a narrative emerged of a product shaped through negotiation, iteration, and collective problem solving. Transfer Explorer’s development was as much about people and process as it was about code and data.

Throughout this report, we describe the development of Transfer Explorer using three broad categories—designing, onboarding, and improving—to help make sense of the distinct yet connected activities that have shaped the tool. These categories are not meant to suggest a fixed or linear sequence. In practice, each has been ongoing, recursive, and intertwined with the others. Decisions made during design have influenced onboarding practices; lessons learned from onboarding have informed improvements; and improvement efforts have, in turn, reshaped both design and onboarding. Understanding this dynamic interplay is critical to interpreting the story of Transfer Explorer as one of continual adaptation and collaborative learning rather than a linear progression from idea to completion.

The sections that follow explore this process using three overlapping lenses—designing, onboarding, and improving. Each represents a continuing strand of work rather than a fixed step. Together, they reveal how Transfer Explorer has been continuously refined through feedback loops, cross-team collaboration, and adaptation to new contexts. Additionally, they illustrate how Transfer Explorer became an evolving platform rooted in collaboration and a shared commitment to improving credit mobility for students.

Designing Transfer Explorer

Transfer Explorer did not begin as a sweeping vision for transforming how credits transfer across institutions. Instead, it emerged from something far more modest: a practical, well-regarded tool developed to solve a large, if very local, problem in New York City. CUNY T-Rex was developed to help students and advisors within the City University of New York (CUNY) system navigate how credits are transferred among its institutions. As of the publishing of this report, CUNY T-Rex has over 240,000 of users and consists of over 1.6 million course equivalency rules that exist throughout the 20-campus undergraduate system serving about 220,000 students. Despite the tool’s limited geographical scope, CUNY T-Rex quickly gained attention. Students used it. Advisors recommended it. And for those involved in its development, the question naturally arose: if this worked at CUNY, why couldn’t something like it work elsewhere?

The idea for the national version of Transfer Explorer was seeded in that question, but its evolution into a multi-state, institutionally integrated platform required far more than a copy and paste of the CUNY T-Rex codebase. From the outset, Transfer Explorer was envisioned as a national tool that would not simply mirror what worked at one institution or system, but consist of a reimagined, scalable platform, built from scratch, that could accommodate the complexities and inconsistencies of transfer data across state lines and institutional types.

Defining purpose and audience

Designing such a tool meant making a series of early, and at times difficult, decisions about purpose, audience, and scope. For some members of the project team, Transfer Explorer was first and foremost a tool meant for students. Transfer Explorer would be a resource to help them understand how their past educational experiences might count toward future goals. For other members of the team, the primary users would be advisors and administrators who could use the tool to improve advising conversations and analyze institutional policies. Still others viewed Transfer Explorer as a lever for broader system-level change, with the potential to surface inconsistencies in credit policies and push institutions toward more transfer-friendly practices. Instead of settling these questions early or narrowing the focus to a single audience, the design process unfolded in ways that allowed various possibilities to coexist to create a multifaceted tool capable of serving multiple purposes and constituents.

When asked about the goals of Transfer Explorer, members of the development and leadership team were on the same page. As they described, its goals are to improve transfer outcomes and to make transfer data more visible and transparent. Credit loss remains one of the most persistent and frustrating barriers for transfer students. These credits are lost in the sense that they cannot be applied toward degree requirements due to incompatibility or excess elective credits, which sets students back in their plans to earn a degree and costs them more money.[18] Citing the value of credit transfer, one member of the product team shared their hope that Transfer Explorer can be a potential solution to decrease credit loss. Another team member summarized the goal of Transfer Explorer succinctly: “we are trying to help prospective transfer students research their options such that they can more successfully complete their studies with less time and less money and less waste and inconvenience.”

“We are trying to help prospective transfer students research their options such that they can more successfully complete their studies with less time and less money and less waste and inconvenience.”

Making data more visible and transparent

One of the ways Transfer Explorer aims to improve transfer outcomes is by making data more visible and transparent. As one respondent put it, “the primary function is to be able to clearly and transparently explain to anybody that’s using the site how their credits will move around, how they will apply, and facilitating discussions between students, advisors, [and] other people that help them.” In order to do this, Transfer Explorer takes internal institutional data such as course catalogs, equivalencies, and degree requirements and makes them available externally, sometimes for the first time.

Several members of the product team highlighted that showing credit applicability sets Transfer Explorer apart, noting that Transfer Explorer may be “the only platform that’s trying to connect not just the transferability but the applicability of credit.” This focus on applicability is possible because Transfer Explorer prioritizes incorporating degree and program requirements into its design. Rather than showing equivalency alone, the tool highlights how courses fit into specific programs of study and degree pathways, giving students and advisors more meaningful and actionable information about progress toward a credential. In so doing, Transfer Explorer brings to light “transfer opportunities that are currently obfuscated, not by malice, but by just the challenge of showing information to people.”

Transfer Explorer brings to light “transfer opportunities that are currently obfuscated, not by malice, but by just the challenge of showing information to people.”

One state lead shared the role Transfer Explorer can play in centering students in the transfer experience and helping to build trust between students and institutions: “Transfer Explorer is a really key part of transparency in institutions showing up for students and institutions being student ready. I don’t think it’s a root cause solution. I think it’s a transparency opportunity that really matters for students also having trust and buy-in with institutions.” Similarly, a member of the product team noted that Transfer Explorer provides a chance for institutions to proactively improve students’ transfer experience: “the opportunity is to help demystify this part of the transfer process, and I think it comes with the opportunity for institutions to think about what that data looks like when students use it as well.”

Exploring options and empowering students

Members of the team were aligned on seeing Transfer Explorer as a tool that allows students to explore their options when it comes to transfer and empowers them to make decisions about their educational journeys. “It’s an exploratory tool for students who are looking to transfer, making [information] easily accessible and user friendly, ensuring that it’s not too overwhelming for students and even other stakeholders who are using the tools,” noting the importance of those who support students such as advisors, faculty, and family members. Another member of the team echoed this: “the purpose of this tool is to provide empowerment and clarity for the students that we serve, and to also incorporate the people that immediately help them as well.”

Meeting students where they’re at is also critical to the mission of Transfer Explorer; one member of the product team described how design choices have centered students from the beginning: “We have always focused on being mobile first. So our understanding is that students in general are going to be on their phones. They’re going to be on mobile devices. And so our design is built for that experience.” This design choice differed from CUNY’s T-Rex, which was designed to be viewed on a desktop, and it presented the additional challenge of optimizing the design to clearly and effectively communicate the complex information on a more compact screen. To accomplish this, Transfer Explorer brought in a dedicated user experience designer at the beginning of the project.

In addition to designing a user experience that will resonate with students, Transfer Explorer is designed to help students take the first step to communicate with their potential transfer destinations. One team member highlighted the importance of the communication features, which are still in their early stages, saying that they hope students can take “whatever journey they want to conjure up for themselves, and after they do that they can talk to somebody about that, so they feel more empowered than they do right now to have these conversations and to speak up for themselves when it comes to their academic future.”

Building for integration and accuracy

From a technical standpoint, one of the earliest and most defining decisions was to build Transfer Explorer as a live, data-integrated tool. This choice increased the complexity of the design process but reflected a shared belief that static tools would not be sufficient to meaningfully improve credit mobility.

Rather than requiring institutions to upload spreadsheets or maintain separate databases, Transfer Explorer draws directly from student information systems using efficient methods, such as API integrations or automated data feeds using secure file transfer protocol (SFTP), to collect data related to course catalogs, transfer tables, and degree requirements. This process provides more accurate and the most up-to-date information. This direct connection is a valuable aspect of Transfer Explorer, streamlining the work necessary to maintain the resource, and it reduces administrative burden on the institutions. As one team member explained,

Other products are operating more on file transfer, maybe not as regular updates, or […] maintaining two systems. So a college would be maintaining their source system, but then also maintaining this external database that is public facing. I think we are special because we are not asking…you to do more work. We’re just asking you to validate the information that you’re seeing. It should be what you see in your SIS or degree audit system. And if something needs to change, change it there, and it’ll be reflected over here.

To support that technical integration, the project team contracted with DXtera, whose expertise in system interoperability and student information system (SIS) data architecture helped ensure that Transfer Explorer could function across a wide variety of student information systems and institutional contexts. At the center of this effort was the Labs team, which led the product’s incubation within ITHAKA. The Labs team brought deep expertise in user-centered design, but Transfer Explorer also required navigating a new and unfamiliar domain: institutional transfer credit systems. That learning curve was steep. As one team member reflected, “Most of what the Labs team had done before this had to do with scholarly communication and research… This gets into a different part of the higher education enterprise, and so it’s required a different level of domain expertise.” The collaboration with DXtera helped bridge some of that gap, particularly in translating institutional data requirements into a common framework that Transfer Explorer could operate within.

These integration efforts and collaborative approach were especially critical given the fractured state of credit transfer information. Although some partnerships, pathways, articulation agreements, and static transfer guides can be useful to students looking to transfer well-traveled paths, information can be harder to find for students transferring to a different system or across state lines. Transfer Explorer currently brings together transfer-related data from institutions spanning four states and five different student information and degree audit systems, producing a single source that “aggregate[s] information about credit mobility into a format that is understandable and usable by anybody.”

Still, integrating with so many disparate systems and software has not been without its challenges. At the beginning of the project, nonprofit partner DXtera had built connectors for some of the common student information systems—Ellucian Banner, Degree Works, and PeopleSoft—and was working on building others. This impacted which colleges and universities could join the project in its pilot phase, with several states choosing to begin with institutions that use Banner or PeopleSoft to store their transfer data. As the project progressed, institutions that use Ellucian Colleague and Jenzabar were able to join as well.

In addition to the different student information systems, the onboarding process revealed substantial variation in how individual institutions used their systems. These differences required school-specific configurations, or “instances where colleges need some additional kind of customization to be able to make the tool make sense.” In some cases, this meant adjusting how the search function pulled program information or changing the design of the results page to more effectively display types of elective credits.

Institutional policies, definitions, and behaviors added further complexity. School-specific configurations can arise from a variety of factors, including the way institutions handle certain types of credits or the way they are documented in their system. One member of the product team described encountering these customization needs:

Colleges have their systems, obviously, but then they have all sorts of policies tacked on top of their systems that are not inherently part of what it is that we’re pulling. So every time a student transfers a stat course, the lab is waived. It’s like, okay, cool, but that’s not in the audit language, so it’s written somewhere on a website, and it’s what happens when a student actually transfers. But it’s not something we would ever know from connecting to our source system.

These policies underscore the importance of working in close collaboration with institutional partners. Though the data are automatically incorporated into the platform, institutions must still verify the data to ensure users are provided with accurate and complete credit mobility information.

While this presents a challenge, the product team also saw an opportunity to continue working towards Transfer Explorer’s goal of bringing clarity to disparate transfer information. As a member of the product team summarized:

The solution is gathering as much information and requirements as possible and then trying to get creative in the front end development side of things, while still maintaining some level of consistency. And, you know, we can’t have a wildly different results screen for every college, because we want students to have a similar experience as they’re exploring different colleges.

These early efforts to identify individual needs and policy gaps also help to inform the onboarding process for future partners.

Overall, the broader scope of Transfer Explorer requires the tool to “handle more complexity in our interface when we’re communicating with students.” As one state lead observed, “we’re not going to dismantle the complexities of an institution, […] but we can build clearer roads so students know how to get through them.”

“We’re not going to dismantle the complexities of an institution, […] but we can build clearer roads so students know how to get through them.”

A foundation for scaling

Throughout the design phase, the iterative and ongoing process of identifying problems and decisions, the team worked closely with internal Ithaka S+R researchers and institutional partners across states. These collaborators not only clarified what kind of data were available (and where), but also helped shape the user experience through feedback loops and early-stage user testing. They raised key questions: Which terms made sense to students? What information did they expect to see first? How should equivalency and applicability be explained?

The design process also involved defining what made Transfer Explorer different. Unlike many existing credit mobility tools that rely solely on equivalency data, Transfer Explorer aimed to focus on course applicability. In this case, applicability is both how a course transfers and counts toward degree requirements. This shift requires additional integration with institutional systems and a more nuanced interface.

In this way, design became less about building a static product and more about developing a flexible, scalable framework—one that could support multiple institutions, adapt to varied data structures, and serve diverse user groups.

In this way, design became less about building a static product and more about developing a flexible, scalable framework—one that could support multiple institutions, adapt to varied data structures, and serve diverse user groups. What mattered most in the design phase was not just building something that worked today, but laying a foundation that could grow with the needs of students and institutions in the future.

Onboarding institutions

After the first three states (Connecticut, South Carolina, and Washington) signed on, work turned to identifying and onboarding the first participating institutions. This onboarding did not mark a discrete stage following design, but rather an extension of it where early design assumptions were tested, revised, and fed back into the ongoing improvement of the tool. Although participation decisions are ultimately left to each state, several key factors were considered in selecting the first group of institutions. Since DXtera had already developed connectors for Banner and PeopleSoft, institutions using those student information systems were considered likely to move more quickly through the process. As DXtera was building or planning to build connectors for Colleague and Jenzabar, institutions using those systems were also possibilities. In the interest of bringing value to the institutions, those colleges and universities with higher rates of transfer between them were seen as strong candidates for inclusion in the early stages of the project. States also needed to consider available institutional resources: did the institution have the capacity to work on the project, or would they benefit from having access to the grant funds that came with participating in the initial pilot phase? Excitement and interest from institutional leaders also played an important role in the decision. In the process of selecting early institutional participants, there was also an explicit interest in including institutions who primarily served in the role as a “sending” institution, an institution that students transfer out of, and as a “receiving” institution, an institution that many students transfer to.

As the first phase of the project began, South Carolina started with two technical colleges and two universities. Connecticut began the pilot with a newly merged state-wide community college system and two universities. Washington identified a pair of institutions: a community college and nearby university. As these institutions worked with DXtera and the Transfer Explorer team to connect, onboard, and validate their data, interest in the tool continued to grow. Each state added several institutions, and these new institutions began their onboarding process before the initial group of institutions were publicly launched.

Initial phase of Transfer Explorer

With the foundational design of Transfer Explorer in place, the team turned to the challenge of piloting the tool in real-world conditions. While the concept had been tested in a single system through CUNY T-Rex, the national ambition of Transfer Explorer meant working across a broader and more complicated landscape of institutions, systems, and state policy contexts.

Instead of starting with a comprehensive national rollout, the project team took a more intentional approach: selecting what has often been referred to as a “coalition of the willing.” These early partners, including state agencies and public institutions across several states, had expressed interest in improving credit transparency and indicated that they had the technical capacity (and institutional will) to engage with the project team through a process that was as much about discovery as it was about implementation.

Piloting Transfer Explorer required institutions to connect their internal student information systems to an external, public-facing platform, posing some challenges, especially during the initial onboarding process. The institutions used a variety of different student information system platforms (e.g., Banner, PeopleSoft, Colleague), each with its own data architecture and implementation quirks. Even within the same state, institutions often differed in how clean or complete their data was, how often it was updated, and who had access. Many institutions also had their own way of storing information within the established platforms, including internal use of symbols or punctuation as well as different conventions used to express similar policies, which needed to be standardized across institutions for a cohesive user experience on the site.

Establishing data pipelines required more than technical coordination; it also depended on a significant degree of trust and institutional cooperation. Participating institutions were asked, sometimes for the first time, to make elements of their internal data—such as course catalogs, equivalency mappings, and degree requirements—available externally through API connections or flat file extracts from student information systems. While the systems themselves remained internal, the exposure of these data to an external, public-facing tool highlighted that the data were often fragmented, incomplete, or inconsistently maintained. Some institutions were understandably cautious about how such information might appear to students and the public, concerned that gaps or inaccuracies could shape student decision-making or create reputational risk.

To help navigate this complexity, state and system leads often acted as intermediaries. Their role was instrumental in coordinating across institutional units and maintaining momentum throughout onboarding. Even with this support, the technical integration process took longer than anticipated. Institutions varied widely in terms of their internal capacity and readiness, and adapting to the architecture of each student information system required sustained collaboration and problem solving between the Transfer Explorer team, institution staff, and the DXtera Institute team.

At the same time, the Transfer Explorer team initiated user testing early in the development process to shape and refine the interface. These early feedback loops focused on how students, advisors, and staff interacted with the tool and how they interpreted the transfer information displayed. The team quickly discovered that many users brought different expectations and levels of familiarity to the process. While institutions tended to focus on the technical side of transfer—whether a course at one institution is deemed “equivalent” to a course at another, and how those equivalencies are documented—students were more concerned with practical outcomes: would their prior coursework actually satisfy a degree or program requirement at the new institution? That insight shifted some of the design priorities, leading to interface updates, clearer labeling, and simplified navigation intended to bridge the gap between institutional data structures and student-centered use.

The initial phase also highlighted responses to the tensions between institutional priorities and student needs. Some institutions were eager to test the tool, even with imperfect data, believing that partial transparency was better than none. Others hesitated, worrying that incomplete equivalency mappings or outdated program information could confuse students or create reputational risk. The project team had to balance these concerns, working with each institution to identify the right time for each to go live on Transfer Explorer while continuing to refine the tool based on feedback.

One refinement that allowed the onboarding process to be more efficient was the implementation of Transfer Explorer’s review site, which allowed data to be privately and asynchronously viewed by institution staff exactly as it would appear on Transfer Explorer. Prior to the development of the review site, institutional representatives would validate this data through a series of meetings with ITHAKA and DXtera teams by walking through complicated decision trees representing their degree requirements.

The initial phase offered critical insight into what it would take to make Transfer Explorer work at scale. It was not just about getting the tech right. It was about navigating local contexts, establishing communication channels, and building shared understanding about what the tool was and was not meant to do.

At times, the team’s assumptions about how the tool would be used were challenged by the outcomes of this testing. Certain programmatic pathways that seemed simple on paper were difficult to display in practice due to incomplete data or sheer complexity. And institutional staff, juggling many priorities, couldn’t always respond quickly to data requests or testing invitations from the Transfer Explorer team.

Still, the initial phase offered critical insight into what it would take to make Transfer Explorer work at scale. It was not just about getting the tech right. It was about navigating local contexts, establishing communication channels, and building shared understanding about what the tool was and was not meant to do. The initial phase also created a set of early champions: states and institutions who saw the potential of Transfer Explorer and were willing to iterate in real time to help it succeed.

As the team prepared for the tool’s public launch, these early experiences proved invaluable. They clarified what needed to be fixed, what could wait, and how to talk about the tool with different audiences. Most importantly, the initial phase reinforced the project’s core insight: that solving credit mobility challenges is not just a technical problem, but a human one. It requires collaboration, transparency, and a shared willingness to rethink how institutions support students moving through higher education.

Going live with Transfer Explorer

After months of design and iteration, Transfer Explorer was ready to go public, at least in part. The team approached the launch as a phased and negotiated process rather than a singular moment. In other words, if going live with Transfer Explorer was like turning on a light, it was done with a dimmer rather than a switch. Each participating institution had different timelines, levels of readiness, and internal considerations to weigh, which meant that going live on Transfer Explorer looked different from place to place.

At the center of the launch strategy was the concept of a minimally viable product—creating a baseline version of the product to allow the team to see how participating institutions respond and identify where further refinement is needed most. For the product team to identify all the elements Transfer Explorer needs to meet the needs of its userbase, it needed to see how users interact with the tools. Therefore, at this stage in the development process, the product team focused on delivering core functionality: enabling users to explore how courses would transfer and apply to degrees at participating institutions, based on real data drawn from institutional systems.

To get there, however, each institution needed to give the green light, and the transition from internal testing to public availability raised a new set of questions for institutions. Was the data accurate enough? Were staff prepared to respond to questions from students or advisors? What would happen if a student made a decision based on information in the tool that later turned out to be incomplete?

These were not hypothetical concerns. Some institutions delayed their launch to do additional data validation or develop internal guidance for advisors. Others moved forward more quickly, viewing the launch as a starting point for continued improvement rather than a final product. One team member described this balance: “Some schools… didn’t want students to see anything until every course was perfect. But that’s not how students use these tools.” In response to this, the Transfer Explorer team decided to offer an acceptance process that would allow institutions to launch first with their course equivalencies, which are typically easier to represent, and continue working to iron out representation of more complicated program requirements.

To support partners during this period, the Transfer Explorer team developed a suite of materials, including FAQs, demo videos, and a communications toolkit, to help staff understand and communicate what the tool did—and did not—do. Still, the capacity to engage with these resources varied widely. Smaller institutions or those with understaffed advising offices often had limited bandwidth to prepare for their institution’s launch. In many cases, the project team relied on state leads to help coordinate outreach and reinforce messaging.

These differences naturally led to variance in how the tool was introduced and promoted by each institution. In some cases, Transfer Explorer was linked prominently from institutional websites or advising portals. In others, it remained in soft-launch mode, with limited visibility to students. This underscored the need for clearer, shared messaging on what Transfer Explorer could do and for whom it was ready.

The team continued to monitor the tool’s performance, track early usage patterns, and field questions from participating institutions. For some institutions, the launch prompted new internal conversations about transfer policies or data governance. For others, it opened the door to additional feature requests. But across the board, one thing was clear: launching Transfer Explorer was not the end of the process. It was the beginning of a new phase—one focused on refinement, iteration, and scale.

Improving Transfer Explorer

The public launch of the first three colleges and universities in February 2025 was a major milestone for the project team and institutions, but no one involved viewed the tool as finished—or even as entering a wholly new stage. Improvement activities were already underway before launch and continued to inform design and onboarding efforts, illustrating how these processes intersect rather than proceed in order. From the beginning, Transfer Explorer was designed with the expectation that it would evolve and be shaped by user behavior, institutional needs, and the realities of messy, inconsistent data systems. Throughout the development process, the product team engaged in a collection of efforts to learn more about how users engage with the tool and then create a roadmap to refine and adapt it over time.

From the beginning, Transfer Explorer was designed with the expectation that it would evolve and be shaped by user behavior, institutional needs, and the realities of messy, inconsistent data systems.

Improvement efforts continued as institutions approved their data and became public on the site. The team monitored usage, questions students and staff raised, and which features worked. Feedback came in through multiple channels: direct conversations with institutions, analytics data, follow-up interviews with key stakeholders, , and extensive user testing, as well as from the Transfer Explorer Community of Practice This group, comprising representatives from each participating institution, convened monthly between November 2023 and July 2025 to review updates to Transfer Explorer, provide feedback on new designs and features, and discuss other transfer related topics.

Starting in early 2024, the senior UX designer on the product team conducted five rounds of user testing, consisting of 93 one-on-one sessions with students, academic advisors, and other faculty and staff across 13 institutions. Each round of testing focused on specific areas of learning, such as assessing how easy the site is to navigate, identifying pain points, and evaluating users’ ability to complete specific tasks within the tool. Additionally, some rounds sought to gather feedback on specific features or potential changes to the tool. Information gathered from these sessions informed the continued development of Transfer Explorer and iterations of the flow and design of the tool.

The product team also gathered feedback from the Early Users Group, consisting of representatives from participating institutions who had been actively involved in the onboarding process and who had shown particular interest in Transfer Explorer. The group convened several times in 2024 to conduct testing and provide feedback on the test site prior to the first public launch at one of the pilot institutions. The group also engaged in asynchronous testing between meetings, and were among the first to have access to the early version of Transfer Explorer.

More informal feedback was gathered during the review sessions where representatives from a participating institution meet with members of the Transfer Explorer team to review and validate their institution’s data. In addition to ensuring information is displayed accurately, these meetings have often surfaced additional feedback related to messaging and student knowledge.

Through these efforts, the product team gathered substantial feedback. Some institutions expressed concerns about specific data inconsistencies or “edge cases.” Others wanted more advanced features or wondered why certain functionalities—such as degree audit systems—were not included from the outset based on their expectations formed from other platforms in this space. In many cases, requests were less about technical improvements and more about clarification: what does this term mean, how was this course matched, why doesn’t this program show up?

The Transfer Explorer team treated these inputs as opportunities to surface friction points and better understand the needs of different user groups. But responding to them required careful prioritization and strategic expansion of the product development team. New team members were added over time as the project evolved and needs were identified, yet the limited team capacity also meant that improvement needed to be scoped and sequenced thoughtfully. Internal conversations often centered on distinguishing between technical issues, enhancement requests, and areas for which clearer documentation or messaging might solve the problem more efficiently than additional development work.

In many ways, the most challenging improvements were not about fixing technical issues, but about aligning expectations. Institutions varied widely in how they understood the tool’s purpose, how they wanted to use it, and how they interpreted student needs. One assumed that Transfer Explorer would be primarily used by advisors; another expected it to become a public-facing marketing tool. These differences often shaped what each institution saw as the most important next step, whether it was improved data pipelines, more intuitive search logic, or additional documentation.

Internally, the team also revisited core assumptions about the tool’s audience. Early on, Transfer Explorer was framed as a student-first resource, with simplicity and clarity as top priorities. But as institutions began using it in real contexts, the lines blurred. Advisors, registrars, and state policy staff were increasingly logging on, asking questions, and imagining new use cases. These interactions helped the team recognize that improvement was not just about technical iteration, it was also about rethinking how the tool served multiple, overlapping audiences.

Some changes were rolled out quickly. The team adjusted terminology based on user feedback, added tips to help orient new users, and improved accessibility on mobile devices. Other improvements required more planning, especially those involving deeper system integration or expanded data types.

The team remained committed to continuous, collaborative improvement. Institutions were not treated as customers to be supported, they were collaborators in shaping the future of the tool. This ethos extended beyond product fixes. When institutions raised concerns about data gaps or transfer policy inconsistencies, the Transfer Explorer team used those moments to prompt broader conversations about how they could improve their own systems and practices.

In that way, the process of improvement is not simply about better code or cleaner design. It is about making Transfer Explorer more responsive, more grounded in user experience, and more capable of supporting the complex ecosystem it was built to serve. Improving Transfer Explorer is not just about refining the tool, but also about building trust, deepening relationships, and ensuring that the platform can live up to its potential.

Future of Transfer Explorer

Now that Transfer Explorer has publicly launched at 14 institutions, more information is needed to understand how the tool’s growing user base is engaging with the site and to identify potential pain points that should be addressed. However, improving the tool is an ongoing process, and both internal and external stakeholders have expressed excitement about what the tool could become in the future with new features and functionality to enhance usability and leverage the wealth of data housed within the site to improve credit mobility policies.

Some such developments are already underway. These include new strategies to automate data processing so data are more efficiently integrated into the site, introducing a feature that allows users to contact institutions directly, implementing user accounts, and expanding exploration functionality to allow easy comparison of multiple transfer destinations.

One major update to Transfer Explorer will involve creating a unified list of courses representing all institutions in the tool. Currently, when users begin an exploration, they are only able to input prior coursework that aligns with the available data of the destination institution they select. This means that a student cannot change their destination school without re-entering information about their prior coursework. Moreover, they cannot enter prior coursework that the destination school has not yet evaluated. A unified course list will expand the universe of courses a user is able to select from when inputting their transcript details into the tool, ensuring the student is provided with more accurate transfer information and allowing them to more easily compare destination institutions.

One recurring theme of functionality currently being explored are the ways in which newly available technology such as generative AI can assist with credit transfer. The product team sees the deep connections that Transfer Explorer is establishing with institutional data as a tremendously powerful foundation on which to leverage new tools. They are investigating ways to integrate generative AI and machine learning into the platforms, such as enabling transcript upload and automated analysis, enhancing data transformation processes, analyzing equivalency data to produce system- or institution-level insights, and developing tools that can generate or suggest new equivalencies.

Other developments are still in the planning stage. For example, incorporating credit for prior learning (CPL) into the platform is currently a top priority for the product team. CPL policies allow students to earn college credits from validated experiences including military service, workforce training, and external exams (e.g., CLEP, AP). These policies can save students significant time and money by allowing them to bypass coursework that they have already mastered, but CPL policies can be highly complex and vary widely across institutions. The integration of CPL policies into Transfer Explorer could therefore drastically improve transparency for users, especially if this use can help the transfer community to settle on de facto standard treatment of common CPL needs. The product team plans to integrate CPL policies into Transfer Explorer in phases grouped by the credit source, with an initial focus on credits from external exams.

State leaders have expressed strong support for integrating CPL policies into Transfer Explorer. In addition to improving credit mobility transparency, one state lead explained how they think the integration of CPL into Transfer Explorer could serve as the impetus for institutions to shift their credit mobility policies from focusing on course equivalences alone to students’ specific learning outcomes.

The product team is also seeking to improve how the platform presents information to users who have already earned an associate degree or completed coursework aligned with an applicable direct transfer agreement. These methods would increase transparency within Transfer Explorer by helping users to more clearly understand how their earned and prospective credits fit within the credit mobility policies in their specific transfer context. As a state lead explained, direct transfer agreements are not reflected within institutional data systems, “so it becomes course-to-course equivalency, and what happens in our direct transfer agreement is it actually should just give you the block equivalency of meeting all [of] your gen eds at your transfer receiving institution if they’re part of the agreement.” Therefore, “the ability to have direct transfer agreements show up as the chunks that they are [in Transfer Explorer] would be a huge asset.” The product team is now working to test related features with a single institution before implementing more widespread changes to the tool.

Developments under consideration

The product team is currently conducting research on the feasibility of several potential updates to the platform. One update under consideration is focused on the first step in creating an exploration on the site, when users must provide information on the courses they have completed thus far. As one developer explained, current users must manually enter their prior coursework into the tool, and that process can be time consuming and even overwhelming for some users. Integrating a feature that would allow students to more efficiently and seamlessly upload their prior coursework into Transfer Explorer could drastically improve the user experience. Other members of the product team have emphasized how integrating a way for students to request their transcripts within Transfer Explorer could help the tool be more student-centered and responsive to barriers students face when making transfer plans. Although institutions have processes in place for students to request transcripts, a built-in tool could cut down on the additional steps needed to do so, thereby making the process more efficient for both students and institutions.

The product team has also described how Transfer Explorer could be leveraged to provide students with recommendations for programs and institutions that make the best use of the credits they have already earned. For students who are unsure about what they want to study or where they would like to transfer, these personalized recommendations could be highly useful and help them save time and money by steering them to programs that are well-aligned with their prior coursework.

Beyond the student user experience, the product team is highly interested in the ways in which the site can leverage course equivalency data for expanded institution-facing functionality and usability.

I would like to see some functionality that is specifically targeted to administrators at institutions so you know, showing and maybe recommending how to fill gaps in equivalencies, providing analysis of program requirement alignment across institutions, providing insights about how users are exploring data for their institutions, and what that might mean for their strategy.

Institutions could access a dashboard on the site’s backend that provides “more tooling and visibility for schools to track their data, to track the leads that this generates, to improve their data as they’re onboarding it. This would allow the institution to take ownership of utilizing the rich information Transfer Explorer provides to assess the effectiveness of their credit mobility policies and make strategic improvements.

Future growth

The product team members and state leaders we interviewed described their Transfer Explorer wish lists as well, envisioning what the tool could become once it has grown its user base to a much larger scale. At this time, the product development team is focused on emphasizing the value of the tool to a single student, institution, and system, and is therefore not currently conducting research on the feasibility of implementing these features or functionalities. However, Transfer Explorer is continuously evolving in order to better serve its users and create better credit mobility outcomes, and these ideas showcase prospective avenues for innovation.

Potential updates could include the ability to do side-by-side comparisons of explorations across programs and institutions, to provide more clarity on how course transfer may differ between the transfer options a student is considering. Members of the product team have also discussed how a course search feature could improve usability by allowing users to do more focused explorations, such as investigating how a summer course would transfer to specific institutions.

Transfer Explorer could also provide users with greater insight into the ways in which their degree programs are aligned with specific career paths. Some of the developers have described how, in the future, the site might be able to review user information to provide recommendations for programs at destination institutions that are aligned with the careers it appears a user is well positioned to pursue given their course credits.

Given the wealth of data housed within the tool, Transfer Explorer could potentially be leveraged to provide institutions with recommendations for new course equivalencies to consider when determining how credits will transfer into their institution. As one developer shared, “Articulations are kind of a nightmare for them, and I think it’s not our role to tell schools these courses should be equivalent, that’s really their call. But we will increasingly be sitting on data that will make it easy for us to make suggestions.” The developer further explained,

Like this course is equivalent to this course, which is equivalent to this course, so maybe these two should just be equivalent?…We have a lot of data we could use to make those sort of recommendations and suggestions, and we could also feed into that with our knowledge of what courses students look for that don’t transfer. Right now it’s like, well, we know that a lot of people want to transfer this course to your school, maybe it should be equivalent to something.

As the tool grows and incorporates more institutional data, it may then become possible for Transfer Explorer to generate recommendations for standardized course equivalencies for the field at large. “I feel like lurking inside of our data there’s secretly a union catalog for the whole country,” one developer shared. “We can build the notion of sort of nation-wide equivalencies and…all the different ways a course can be represented in different catalogs.” Given the significant complexity of credit mobility policies across the country, a tool that can crosswalk these policies to clearly identify equivalencies and suggest strategies to streamline language and procedures could have significant impact for the field of higher education.

Discussion

The development of Transfer Explorer demonstrates that solving credit mobility challenges is as much about people, policy, and process as it is about technology. Moreover, these processes are neither static nor sequential. Designing, onboarding, and improving unfold simultaneously, feeding into one another as the tool and its community of partners continue to evolve. Although the tool itself now allows users to see how credits transfer and apply toward degrees at participating institutions, the path to its creation was neither straightforward nor linear. Instead, it required sustained collaboration among technical teams, researchers, state leaders, and institutional staff including institution leaders and transfer professionals; a willingness to adapt to varied policy and system contexts; and an understanding of the realities of existing data, infrastructure, and team capacity.

Lessons from the development process

Several themes stand out across the stages of design, onboarding, and improvement.

- Clarity of purpose can coexist with flexibility. From the outset, Transfer Explorer’s core aim—to make credit transfer information more visible and transparent—remained constant. Yet, the project team resisted narrowing its scope to a single user group or policy aim, instead allowing the tool to evolve in ways that served students, advisors, and institutions. This flexibility proved valuable in navigating differing expectations and adapting to unique institutional contexts.

- Integration is both the innovation and the challenge. By pulling data directly from student information systems and degree audit systems rather than creating a separate system, Transfer Explorer addresses a major limitation of many existing credit tools. This automated integration supports accuracy, reduces maintenance burdens for institutions, and enables the display of credit applicability in addition to transferability. But achieving it required complex technical work, custom configurations for individual schools, and navigation of occasionally undocumented institutional policies—underscoring that technical innovation depends on organizational readiness and trust.

- The initial phase is about relationships as much as testing. Early work with institutions revealed that data integration and interface design were only part of the equation. State leads served as essential intermediaries, building confidence among institutions and troubleshooting challenges. The piloting process also exposed differences in the comfort with releasing incomplete data and prompted important conversations about transparency, reputational risk, and student needs.

- Going live is a beginning, not an endpoint. While public availability marks an important milestone, early launches varied in visibility and promotion, reflecting differences in institutional culture and readiness. This underscored the need for clear, shared messaging about the tool’s purpose and capabilities, as well as ongoing support for integration and adoption.

- Continuous improvement requires intentional feedback loops and careful sequencing. Throughout the process, the team established multiple channels for gathering input—from formal user testing and early user groups to informal review sessions. These processes allowed the tool to be refined in real time, but they also included difficult feedback which revealed tensions between institutional priorities, technical capacity, and user needs. For a small, mission-driven team, prioritization became critical, with some improvements requiring deeper system changes and others achievable through adjustments to language, documentation, or interface. Beyond this, adjustments were not failures, but reflections of a thoughtful process of scoping, sequencing, and responding to real-world constraints.

Why process matters

Although the ultimate measure of Transfer Explorer’s success will be its impact on student outcomes, understanding its development process provides important context. The challenges faced and strategies employed here are relevant to any effort to improve credit mobility at scale or to develop an educational technology tool that draws from a complex web of institutional or system-wide data systems. The insights of this report are also relevant to any initiative seeking to build a tool that is primarily mission-driven rather than profit-driven, often with limited resources and a small team. Technical integration across varied systems, building and maintaining institutional trust, aligning the tool’s design with multiple audiences, and sequencing improvements to match capacity are not unique to this project. By making these dynamics visible, this report provides a practical reference for states, systems, and institutions considering participating in similar initiatives.

Process documentation also helps demystify the work for stakeholders outside the immediate project team. Funders, policymakers, and institutional leaders can better appreciate the timeframes, resources, and partnerships required; technical teams can anticipate integration hurdles; and advisors and faculty can see how their roles fit into building and sustaining such a tool.

Looking ahead

As of Fall 2025, the platform contains more than one million course equivalency rules across 14 destination institutions in the live version accessible to the public. Its current features enable users to explore both the transferability and applicability of prior learning, but the product team and state leads have articulated a vision for continued growth and are actively seeking ways to improve the site. Specific planned and potential updates include:

- Expanding functionality for saving and sharing explorations.

- Incorporating credit for prior learning policies.

- Developing a unified set of courses to improve exploration building within the tool.

- Additional features to make it easier for students to use the tool, including side-by-side comparisons, career pathway alignment, and more streamlined transcript data entry.

- Using generative AI and machine learning to enhance functionality, such as enabling student transcript upload and automated analysis and suggesting new equivalencies.

- Building institution-facing dashboards to analyze equivalency coverage, alignment, and user engagement.

These directions reflect an ongoing commitment to making the tool more student-centered while also serving as a resource for institutional strategy and policy improvement.

Conclusion

The story of Transfer Explorer’s development is one of collaboration across boundaries—technical, institutional, and geographic. By documenting the process, we see that building an effective, scalable transfer tool requires more than code. It requires sustained partnership, a willingness to adapt to local contexts, and a shared commitment to transparency and equity in credit mobility.

Transfer Explorer is still evolving, and its broader impact on student outcomes will take time to assess. In future research, we hope to learn more about how Transfer Explorer, and any changes to policy or practice it inspires, influences important pieces of the transfer puzzle, including credits transferred and applied and time to degree completion.

In the meantime, the process of creating Transfer Explorer has offered lessons of its own for the project team and their institutional collaborators: start with clear goals but remain flexible in approach; invest in relationships alongside technology; integrate data in ways that reduce burden and improve accuracy; and treat launch as the beginning of an ongoing cycle of improvement. These lessons, and the candid insights of those who helped bring the tool to life, can help others navigate the complex but essential work of making higher education transfer more efficient, equitable, and transparent.

Acknowledgements

This report was made possible through generous support from the Gates Foundation and Ascendium Education Group. The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the positions or policies of these funders. We also thank the individuals whom we interviewed for this report for their time and candid feedback. Your dedication to improving credit mobility is inspiring and we deeply appreciate you sharing your experience developing Transfer Explorer with our team. Any errors or omissions remain the fault of the authors. Additional thanks to all who reviewed drafts of the report, including Kimberly Lutz and Juni Ahari for copy edits and formatting.

Appendix A. Timeline

The following timeline provides a high-level overview of key milestones in the creation of Transfer Explorer, beginning with it receiving grant funding distinct from CUNY T-Rex, through the time of this publication.

Appendix B. Interview guide

Note: This is a very loosely structured protocol because each individual conversation will be tailored to that person’s unique history and knowledge of Transfer Explorer.

Product Team Guide

General Questions

1. Describe your role in the development of Transfer Explorer.

-

- Probe: When did you get involved?

- Probe: What were your responsibilities around Transfer Explorer at the beginning of your involvement? How have your responsibilities evolved since then?

- How does the work you’ve done with Transfer Explorer compare to your previous job responsibilities?

About the Transfer Explorer Product

- What is your understanding of the purpose and goals of Transfer Explorer?

- Probe: What would you say are the most important features/functionalities of Transfer Explorer?

- How does Transfer Explorer compare to other available transfer-related and credit equivalency-related tools?

- Probe for management: What makes Transfer Explorer unique among these other tools?

- In what ways is Universal Transfer Explorer similar to or different from CUNY Transfer Explorer?

- In what ways has your knowledge of or experience with T-Rex influenced the development of Transfer Explorer?

- Do you think people need training in order to use Transfer Explorer effectively?

- Probe: If so, what kind and should training differ for different stakeholder groups (students, advisors, etc.)?

If so, how? - Probe: What supportive features do you think are

necessary to include on the site (such as FAQ, videos, etc.)?

- Probe: If so, what kind and should training differ for different stakeholder groups (students, advisors, etc.)?

Development of Transfer Explorer

- Tell me about your understanding of the process by which Transfer Explorer was first developed and how it has evolved since then.

- How were stakeholders engaged or involved throughout the development process?

- Which institutional stakeholders have you interacted with, and in what context(s)? How have these interactions impacted the development of Transfer Explorer?

- Probe: Students, institutional, community stakeholders, funders

- What were the most significant challenges you faced during the onboarding, development, design, and launch (as relevant to your role on the project) of Transfer Explorer?

- Did you overcome these challenges? If so, how?

- If not, what prevented you from doing so? What, if anything, would you need to overcome these challenges?

- Describe the collaborative process of working with another organization (DXtera) and other departments at Ithaka (as applicable to your role) while developing Transfer Explorer.

- Probe: Thinking about the overall collaboration, what were/are some of the benefits and challenges?

- Describe the approach taken to ensure the Transfer Explorer product is accessible.

- Accessibility in this context means usability, knowledge of the tool, navigable to all stakeholders who need it, including people with disabilities.

UX/UI Specific Questions

- Describe the approach taken to incorporate user testing in the development process of Transfer Explorer.

- Probe: What groups of stakeholders have participated in user testing?

- Probe: How did user testing differ for different stakeholder groups (advisors and students vs. early user group)?

- What changes have been made as a result of user testing?

Dev/Data Specific Questions

- Were there institutional or state practices that enabled the development of Transfer Explorer (e.g. data policies, transfer policies, common course numbering, etc.)?

- Were there state or institutional practices that hindered the development of Transfer Explorer?

- Probe: How did you overcome those challenges?

- To your knowledge, has Transfer Explorer resulted in actual or considered changes to any system or institution’s practices and/or policies? If so, how?

Improvements to Transfer Explorer

- What features or improvements would you like to see added to make Transfer Explorer more effective?

- How would those features or improvements make Transfer Explorer work better for students, advisors, institutions, etc.?

- What would be needed in order to make those improvements happen?

- Probe: changes to the data at the institutional level, additional staff or funding, better understanding of the data, partnerships

Concluding Questions

- Is there anything else that we didn’t get to today that you think our team should know?

State Lead Guide

General Questions

- What is your current title or position?

- Probe: How long have you been in this role? What were you doing before that?

- Probe: Tell me about the structure and governance of your organization/agency.

- How did you come to learn about Transfer Explorer?

- What is your understanding of the purpose and goals of Transfer Explorer?

- Probe: What would you say are the most important features/functionalities of Transfer Explorer?

State and Institution Context

- How does Transfer Explorer fit into your state’s strategic plan and vision surrounding transfer?

- Describe the process you used to determine which institutions from your state would be part of the first cohort of institutions to participate in Transfer Explorer.

- Probe: What criteria did Ithaka provide? Did you have additional criteria?

- Probe: How did the institutions you selected decide to participate?