CIC Consortium for Online Humanities Instruction II

Evaluation Report for First Course Iteration

-

Table of Contents

- Preliminary Findings

- Data Sources

- Limitations

- Description of Courses and Participants

- Instructor Experience

- Student Experience

- Student Learning Outcomes

- Overall Assessment

- Stakeholder Interviews

- Preparing for the Next Iteration of Courses

- Conclusion

- Appendix A: List of Data Elements Requested

- Appendix B: Rubric for Peer Assessment

- Appendix C: Instructor Survey

- Appendix D: Student Survey

- Appendix E: Interviewee List and Interview Scripts

- Endnotes

- Preliminary Findings

- Data Sources

- Limitations

- Description of Courses and Participants

- Instructor Experience

- Student Experience

- Student Learning Outcomes

- Overall Assessment

- Stakeholder Interviews

- Preparing for the Next Iteration of Courses

- Conclusion

- Appendix A: List of Data Elements Requested

- Appendix B: Rubric for Peer Assessment

- Appendix C: Instructor Survey

- Appendix D: Student Survey

- Appendix E: Interviewee List and Interview Scripts

- Endnotes

The CIC Consortium for Online Humanities Instruction began in 2014 with the support of The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The success of the first Consortium motivated the Mellon Foundation to support a second Consortium that was formed in the summer of 2016 with teams of faculty members and administrators from 21 institutions that were selected through a competitive process.[1] Each institution is represented by a four-member team including a senior academic administrator, two full-time faculty members in the humanities, and the registrar or representative from the registrar’s office.

The report that follows documents the experience of the 21 participating institutions during the first year of the Consortium II initiative. The data refer only to the courses developed for the project and the reactions of faculty and students to those courses. While it may be interesting in future reports to compare the experiences of Consortium II to those of Consortium I, comparisons are not included here.

The initial round of online courses developed for this Consortium was offered during the Spring 2017 semester. Courses will be revised and opened for enrollment by students from the other participating institutions during the 2017–2018 academic year. This interim report documents the first year experience of the second Consortium.

The CIC Consortium set out to address three goals:

- To provide an opportunity for CIC member institutions to build their capacity for online humanities instruction and share their successes with other liberal arts colleges.

- To explore how online humanities instruction can improve student learning outcomes.

- To determine whether smaller, independent liberal arts institutions can make more effective use of their instructional resources and/or reduce costs through online humanities instruction.

Preliminary Findings

At the end of the first year of Consortium II, the participating institutions have achieved a great deal towards each goal:

Goal 1: Building Capacity

Higher education is experiencing rapid change. Online instruction, once relatively rare in the independent sector of higher education, has become more common in just the past few years. When the first Consortium began in 2014, 75% of the participating faculty members had never taught an online course. Consortium II faculty who began in 2016 were considerably more experienced. Twenty-one (21) of the 39 (60%) responding faculty members had taught at least one online course previously, and many of them had taught several such courses. (In part, this was the result of a deliberate change in the selection process for participating institutions.)

The 42 faculty in Consortium II offered 39 online or hybrid courses in Spring 2017. (Because of local circumstances, two courses were offered in face-to-face mode and one was shifted to Fall 2017.) In selecting institutions to participate in the second round of this project, special attention was given to those who proposed to create courses that could be widely used by others in the Consortium. Seventeen faculty created entirely new online courses, 21 modified an existing face-to-face course, and one enhanced an existing online course. More students in Consortium II than Consortium I had already been exposed to online learning, as well. Sixty-five percent of the 320 responding students had taken one or more online or hybrid course before the Spring 2017 semester.

Faculty in Consortium II were comfortable with the technical challenges of online learning. Most faculty (88%) had participated in some kind of training for online teaching, before or during the initial year of this project. Nearly 75% of faculty reported having access to instructional designers and/or instructional technologists to assist with designing and developing their courses, which was a clear value added for some instructors. And nearly all faculty felt adequately prepared to teach online or hybrid courses.

These findings indicate that most Consortium II participants are developing experience with online teaching and learning, are able to allocate resources to support online teaching, and are growing more comfortable with it.

Goal 2: Enhancing Student Learning

A central question for this project is how effective are online and hybrid courses in promoting student learning. Most of the online courses in Consortium II did not have face-to-face counterparts, so it was not possible to conduct a rigorous comparison of student learning outcomes. Instead, we asked faculty to assess their own students’ learning and compared their responses to peer assessments conducted by a group of six humanities faculty from other Consortium institutions. Randomly selected faculty were asked to submit student artifacts that illustrated a command of certain learning objectives. Student work was collected based on a formula for ensuring objectivity. The results revealed that instructors and peer evaluators were closely aligned in their assessment that students demonstrated satisfactory mastery of learning objectives.

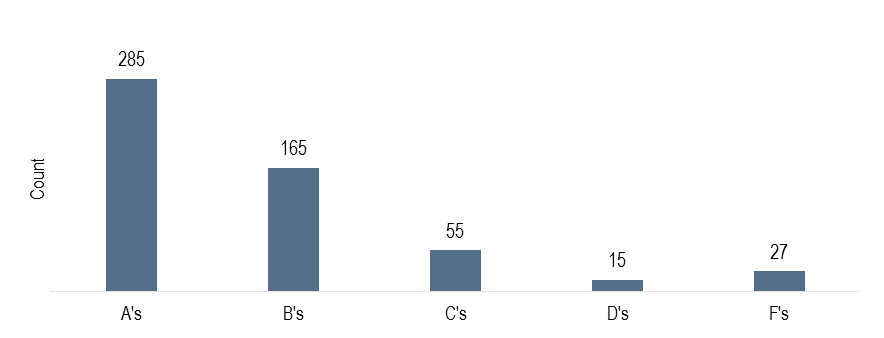

To the extent that course grades are an indicator, courses in Consortium II looked very promising, as over 80% of students in 19 institutions passed their courses with about 55% of them earning A’s. The withdrawal rate in Spring 2017 was also low; over 90% of Consortium students (n=546) remained enrolled throughout the term.

Student engagement is highly prized by liberal arts colleges, and understanding the level of social presence in the online environment is critical to measuring the success of online courses in the liberal arts. An interesting finding to note is that many instructors expressed dissatisfaction with the level of social engagement and sense of community-building among students while the students, for the most part, were quite satisfied with the level of social presence in their online courses.

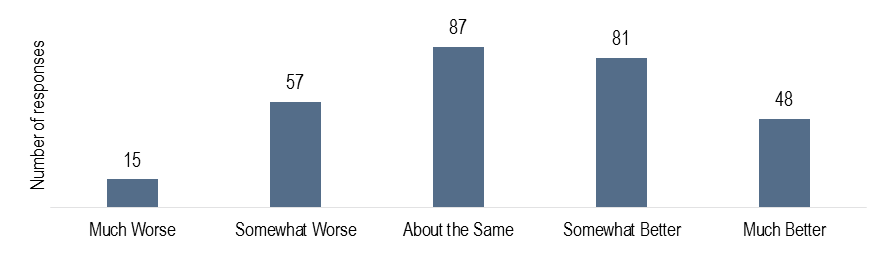

When we asked students to evaluate their experience with the courses and to compare them to traditional in-person courses they had taken, of 280 students responding, 81% rated the experience as good or very good; only 19% rated the experience as fair or poor. Eighty-six (86) students thought the online course was about the same as traditional courses they had taken and 125 rated the online courses as somewhat better or much better than traditional in-person courses.

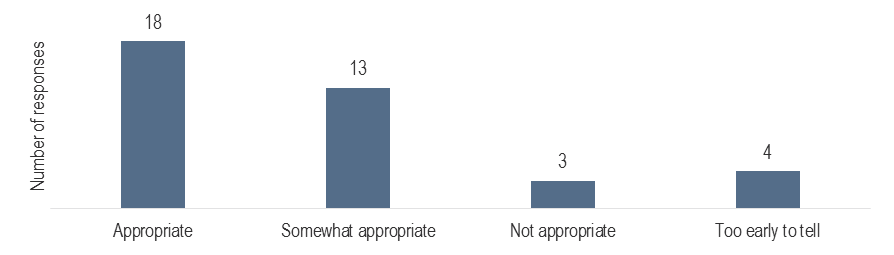

Thirty-one (31) of the 39 responding faculty indicated their overall assessment of the appropriateness of the online/hybrid format for teaching advanced humanities content to be somewhat appropriate or appropriate, while three indicated not appropriate. Four indicated that it was too early to tell.

Students who ranked online/hybrid courses better cited a number of reasons for their response, the most common of which was the increased flexibility that online/hybrid courses afforded. One student wrote:

I have a busy life outside of school, so online classes are easier for me to complete.

Another wrote:

I thought I could complete the requirements early in the semester.

Faculty also rated online teaching positively:

In this particular course, we often tackle controversial issues. In the face-to-face course, I often find students rather reticent to enter into discussion. The online students seemed to have no reticence at all. I did have to offer constant guidance about how postings should be based on the course texts and concepts and not just an opportunity to express opinions. But, overall, I was pleasantly surprised by the display of enthusiasm with which the students participated, and that enthusiasm seemed to last through the entire course…

Online learning, taking into account all of the data we collected, has a number of benefits for student learning. Students appreciated the convenience of online courses, but they were surprised to learn that in many respects, such courses are more demanding than traditional face-to-face courses. When faculty were asked to assess the appropriateness of online learning for teaching advanced humanities content, 80% said online methods are appropriate or somewhat appropriate.

The one disadvantage to online instruction noted by both students and faculty is the loss of some personal interaction between the two groups. This may be especially important in online courses designed to substitute for highly interactive seminars.

Goal 3. Increasing Efficiency

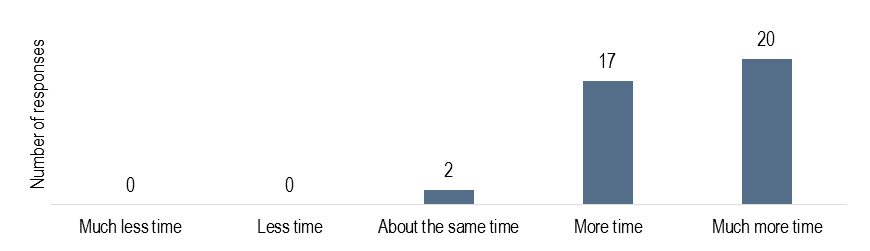

This goal has been the hardest to evaluate. When the first Consortium was launched in 2014, we asked all the participating faculty members to record their time spent on developing and delivering online and hybrid courses. Our intention was to measure cost savings over time. The experience of the first Consortium helped us understand that collecting timesheets from faculty was not productive. It is clear that online and hybrid courses entail additional start-up costs in terms of faculty planning time and support costs, not to mention the technology infrastructure. Eventually we may be able to determine if having online courses available for students will allow colleges to offer additional courses without adding faculty costs, but calculating such savings is not possible at this time. While instructors may well save time in the second iteration of offering these courses, faculty at the end of the first year’s experience reported that planning and developing online courses certainly took more time.

This is consistent with other research. Of the 39 faculty responding to the Consortium II survey, only two thought that developing online courses takes the same amount of time as developing a comparable face-to-face course. Thirty-seven (37) reported that when comparing the two delivery modes, online courses take more time or much more time. When thinking about the time it takes to teach online courses, compared to face-to-face courses, the results were similar. Three instructors thought online courses took much less time; 14 thought they took about the same amount of time; 22 thought the online courses took more time or much more time to teach. When courses are offered to others in the Consortium in the second year of the project, we will be able to make more definitive statements about achieved efficiencies.

Preliminary Conclusion

Our preliminary conclusion from the first iteration of courses is that online learning can be an appropriate format for delivering upper division humanities courses. Evidence from the first iteration of courses indicates that online instruction can be implemented successfully and, under the right circumstances, in ways that are consistent with the mission and goals of liberal arts institutions. Students appreciate the flexibility afforded by such courses and their learning outcomes are similar to those achieved in traditional classroom courses. While faculty are concerned that student engagement is not as strong in online courses as in face-to-face courses, students rated engagement in online courses to be the equivalent of engagement in traditional courses. The next iteration of these courses will provide an opportunity to further interrogate these findings and, in particular, to investigate the impact and feasibility of cross-enrollment within the CIC Consortium.

Takeaways from the Workshop in August 2017

Participants in the workshop held at the conclusion of the Consortium’s first year in Washington, D.C., on August 7-9, 2017, confirmed the findings of our evaluation. Some of the key takeaways that emerged from the workshop presentations and discussions include:

- Many of the workshop participants agreed that comparing online versus face-to-face courses with just the standard learning outcome metrics, such as final course grades, is not very productive. Online courses offer different ways of engaging with the course and require different preparation and tools for both students and instructors.

- Many instructors realize that a large number of today’s students are not “traditional.” Many are older, live off campus, work full-time, have extensive family commitments, and seek alternative credential programs. Consequently, the instructors and administrators recognize that the level of convenience and flexibility that online courses offer to students is an important factor to consider.

- Many instructors believe that part of their responsibility as educators is to prepare students for the digital world. Some argued that not providing students with opportunities to engage in online learning would put them at a disadvantage especially students who already lag behind in such experience.

- The Consortium experience allowed instructors to rethink their pedagogical approaches by becoming more intentional and deliberate about what they want to accomplish in their courses. Many expressed that teaching online helped challenge fundamental assumptions about teaching and learning that they often employ in their traditional classes.

- The Consortium experience allowed instructors to think more holistically about assessing student learning. In addition to coming up with creative ways for students to engage with the course contents (e.g., gamifying the entire course) and demonstrate what they have learned (e.g., providing multiple options for completing assignments), the instructors have begun to rethink what constitutes “student engagement,” recognizing that there are various ways that students can engage with one another in digital spaces.

- The participants agreed that there is a need for rethinking current humanities curricula and course offerings to better meet the needs of the students in a world that is constantly in flux. For some participants, this also means dealing directly with resistance from their colleagues, who are skeptical about the idea of using technology to enhance quality of learning and increase efficiencies in ways that do not adversely affect faculty positions.

Some questions that the Consortium institutions will continue to grapple with during the next year are:

- How can they work collaboratively to identify expertise gaps in each institution and share faculty talent effectively in order to ensure that students will truly benefit from the rich array of advanced humanities courses offered by Consortium institutions?

- How can they provide adequate levels of support for faculty to develop their capacity to teach in new digital environments, in ways that are empowering and enriching?

- And how can they continue to work together to develop effective strategies for tackling some of their most pressing institutional problems in the face of a changing economy (including a decline in student interest in the humanities)?

Data Sources

In order to assess the Consortium’s success in achieving each of its explicit goals, we collected data from multiple sources. These include:

- Registrarial Data [N= 20 institutions]. Student-level registrarial data were collected from Consortium courses of each institution at the end of Spring 2017 term to report course enrollments, course completion rates and grade distributions. Course-level registrar data on the total number of courses offered in-person and online at each institution as well as institutional spending on instruction were also collected (the same data reported to IPEDS[2]). For more information about the specific data elements we requested from the institutions, see Appendix A.

- Faculty Peer Assessment Scores [N= 63 artifacts, 498 scores]. Fifteen (15) randomly selected instructors were asked to designate artifacts from three randomly selected students in their courses to serve as evidence of students’ performance towards each of two predefined learning outcomes. One instructor submitted artifacts from three randomly selected student groups due to the unique nature of the course assignments. Examples of artifacts included research papers, portfolio assignments, or creative endeavors (e.g., creative writing, multimedia assignment, online exhibit). A panel of six evaluators, who were selected from the cohort of participating faculty members, used a four-point scale (i.e., Beginning, Developing, Competent, or Accomplished) to assess how well each artifact reflected the desired learning outcomes. These outcomes related to students’ (1) ability to interpret and analyze texts, as well as their (2) ability to synthesize knowledge. The aim of this process was to assess whether instructors were able successfully to use the online format to achieve general goals of humanities instruction. The rubric, with a full description of the learning outcomes, is included in Appendix B.

- Instructor Scores of Learning Outcomes [N= 38 instructors, 2506 scores]. Each instructor was asked to develop two to four course-specific learning outcomes that were submitted to the research team in January 2017. Instructors included with their learning outcomes a description of how they planned to use the digital tools associated with online/hybrid instruction to help students achieve course-specific learning outcomes. The number of learning outcomes provided by each instructor ranged between two and nine. At the end of the term, instructors were asked to select an assignment to assess all of their students’ course-specific learning outcomes and submit scores for analysis. These scores were also on a four-point scale (i.e., Beginning, Development, Competent, or Accomplished). A total of 38 instructors, representing 20 institutions, submitted their scores.

- Instructor Survey [N= 39 instructors]. This survey was administered at the end of the Spring 2017 term. Sections related to student experience in the online course were derived from the Community of Inquiry survey instrument, which focuses on three constructs: instructor presence, social presence, and cognitive presence.[3] The survey attempted to understand instructors’ perceptions of their preparation to teach an online/hybrid course, their access to quality instructional supports, the amount of time they spent preparing and delivering the course content compared to traditional in-person courses, their beliefs about whether students’ learning outcomes and experience in online courses are comparable to in-person courses, and their reflections on implementation success. All primary instructors who taught an online or hybrid course in Spring 2017 completed the survey. The instructor survey instrument is included in Appendix C.

- Student Survey [N= 37 courses, 280 students]. Student surveys were submitted for all 39 courses, but data from two courses were removed from the analysis because the research team was unable to collect signed consent forms from the participating students. The number of student survey respondents in each course varied between zero and 28. Sections of the student survey were also derived from Community of Inquiry survey instrument and contained a number of items that are similar to the instructor survey. Surveys were administered by the research team on a third-party platform, but instructors coordinated their own students’ participation. The student survey instrument is included in Appendix D.

- Stakeholder Interviews [N= 10 stakeholders]. Additional views on Consortium course quality were collected during stakeholder interviews with a sample of five faculty members, three administrators, and two registrars. A list of interviewees and the interview scripts are included in Appendix E.

Limitations

- Since we were not able to measure student learning in Consortium courses against comparable traditionally taught courses, the student learning outcomes lack a baseline for comparison. As a result, the student learning outcome scores may not reflect the full impact of online instruction on student learning.

- Although we were able to analyze some general trends in online and in-person course offerings by Consortium institutions over the past six years, we could not reliably connect these trends to the data on institutional spending on instruction, which was aggregate of all operating expenses associated with colleges, schools, departments, and other instructional divisions of an institution.

- The distinction between “online” and “hybrid” courses was not clearly defined in the survey instruments we used (nor in the data collected from the institutions’ registrar’s offices). As a result, we were unable to unpack the unique sets of demands and challenges that may be associated with different instructional delivery methods.

- Because all analyses in this report reflect aggregate data, it is difficult to isolate the unique challenges faced by any institution or course.

Description of Courses and Participants

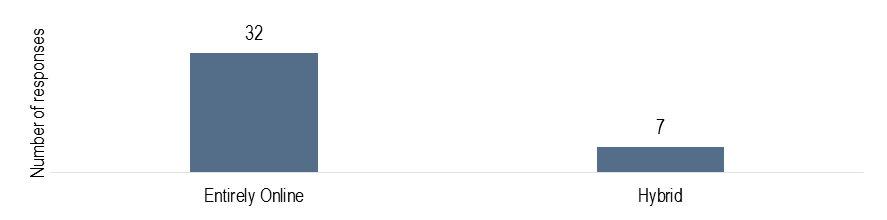

Figure 1: Formats of Consortium Courses

Over 80% of courses offered through the Consortium in Spring 2017 term were entirely online (32 out of 39).

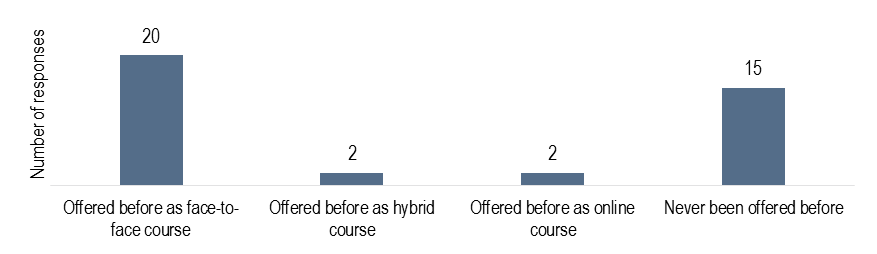

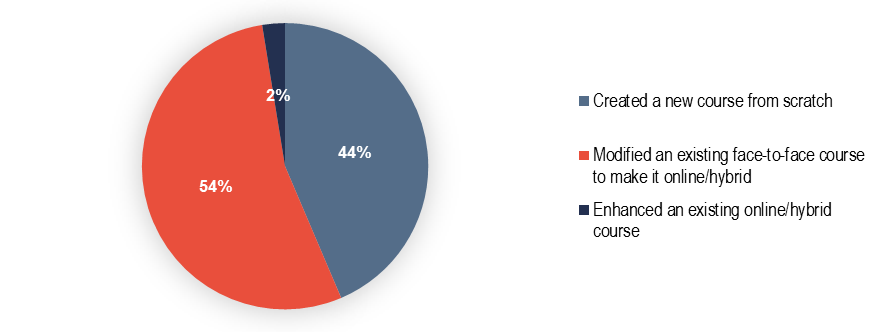

Figure 2: New vs. Existing Courses

Over half of these courses had been offered before as face-to-face courses (51%), while about 38% were brand new courses.

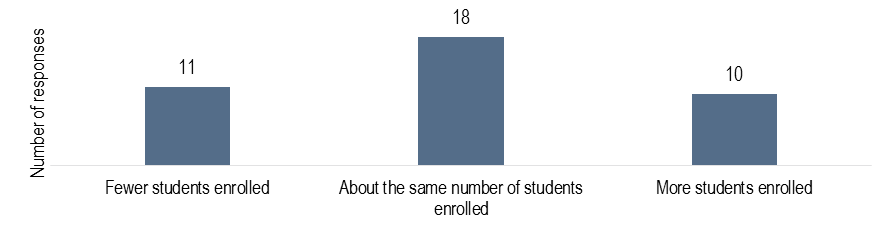

Figure 3: Consortium Enrollments Compared to Typical Course Enrollments

When the instructors were asked to indicate how the enrollment in Spring 2017 Consortium courses compared to the typical enrollment for courses of similar nature at their institutions, 72% of instructors indicated that they had about the same number or more students enrolled in their courses.

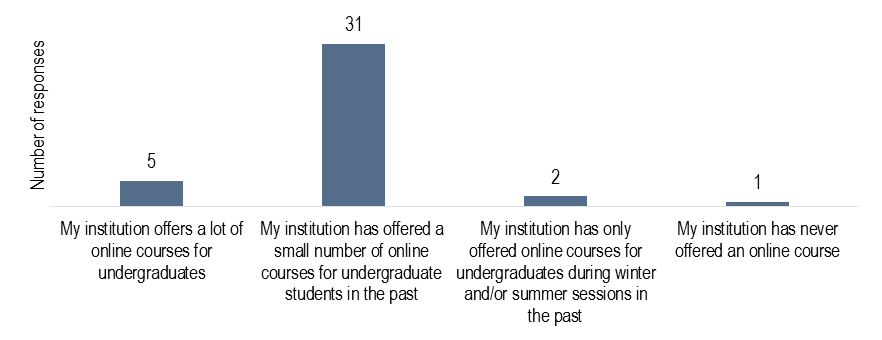

Figure 4: Institutions’ Experience with Online Courses

With the exception of one institution, all institutions had some level of prior experience offering online courses, with about 80% of the instructors reporting that their institutions have offered a small number of online courses for undergraduates in the past and about 13% reporting that their institutions have robust online course offerings for undergraduates.

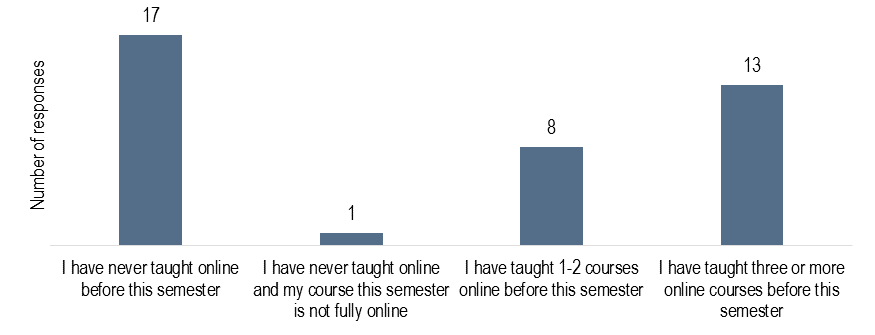

Figure 5: Instructors’ Previous Online Teaching Experience

Forty-six percent (46%) of participating instructors had never taught online prior to this semester while the remaining 54% had experience teaching at least one online course in the past.

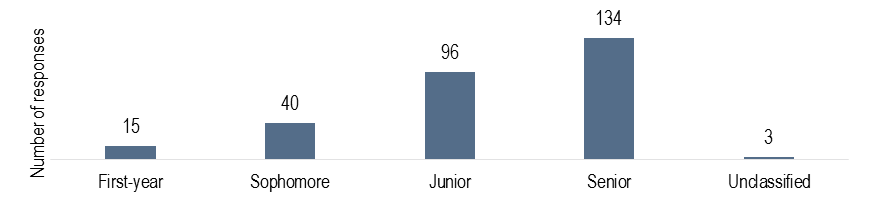

Figure 6: Students’ Class Levels

It is no surprise that 80% of student survey respondents were upper class students (i.e., juniors and seniors), as the courses offered through Consortium in Spring 2017 were upper-level humanities courses.

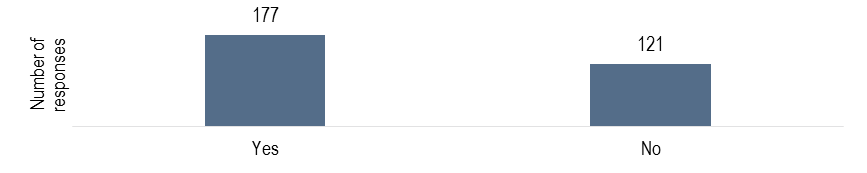

Figure 7: Students’ Previous Experience with Online/Hybrid Courses

About 60% of student respondents indicated that they had prior experience taking one or more of online/hybrid courses.

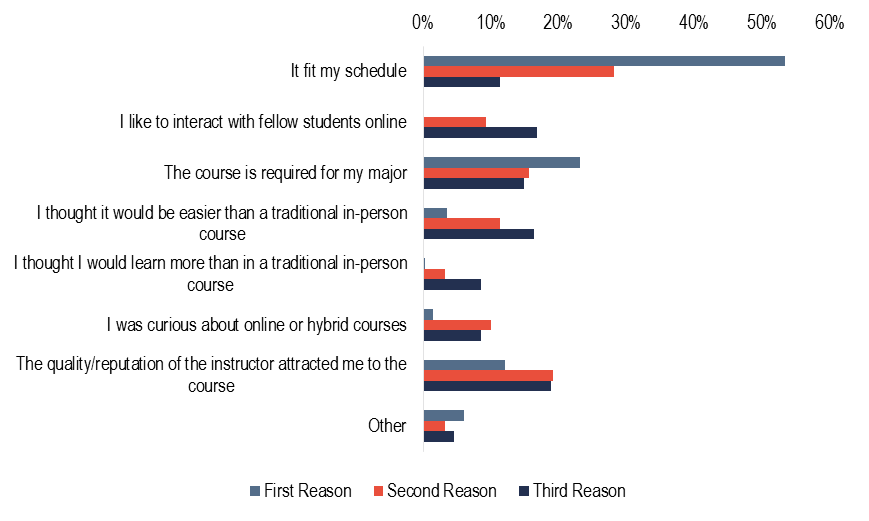

Figure 8: Students’ Reasons for Taking Consortium Courses

The students’ top three reasons for taking the online/hybrid courses offered through the Consortium were: (1) It fit my schedule, (2) The course is required for my major, and (3) The quality/reputation of the instructor attracted me to the course. Over 50% of student respondents chose “It fit my schedule” as the number one reason for taking their courses.

Instructor Experience

Figure 9: Modifications Made to Courses in Spring 2017

Over half of the instructors indicated that they created completely new courses from scratch while another 44% indicated that they modified existing face-to-face courses to make them online or hybrid courses.

Figure 10: Time Spent on Planning and Developing Courses

Online courses generally require more time to plan and develop relative to comparable face-to-face courses. Almost every instructor, with the exception of two, indicated that they spent more time, with more than 50% of the instructors indicating that they spent “much more time” both planning and developing their courses in Spring 2017.

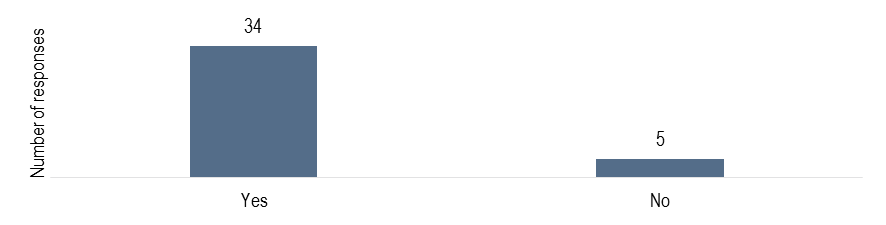

Figure 11: Instructors’ Participation in Training to Teach Online

Most of the instructors (87%) reported that they had some kind of training to teach online both formally and informally before and/or during the semester. Some of these training opportunities included: training offered by CIC, on-campus or off-campus workshops for faculty, courses or certificate programs devoted to online/hybrid pedagogy, campus-mandated training for instructors preparing to teach online, as well as ad hoc sessions with experienced peer instructors or instructional designers among others.

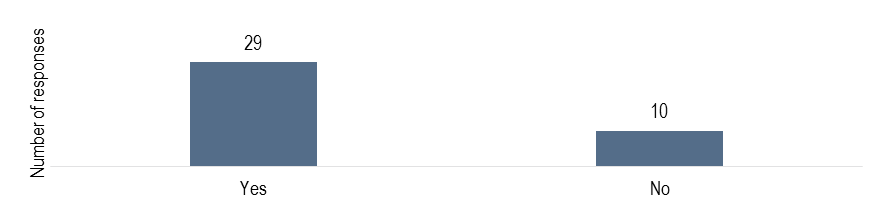

Figure 12: Access to Instructional Designers/Technologists

Seventy-four percent (74%) of instructors indicated that they had access to instructional designers or technologists to support the design and development of their courses, although the amount of time the instructors spent with them varied greatly (i.e., from one to over 40 hours). One faculty member described an especially effective approach to training for online instruction:

My institution offered a 6 day (over two week) period the prior May to myself and another faculty in the CIC cohort. (It was part of a 9 faculty/9 staff session offered every May for faculty innovating in the classroom with IT.) That 6-day period let me start brainstorming class design, scaffolded lectures and assignments, etc. I had 2 IT staff that May and through the fall who spent 15+ hours assisting me with best practices and looked over my course design converting the F2F to an online asynchronous format. They also assisted me in the week or two before it went live. They were amazing.

Figure 13: Instructors’ Experience with Technology in Spring 2017

A relatively small number of instructors indicated that they experienced significant technical challenges in planning, developing, and offering their online/hybrid courses in Spring 2017. Faculty are optimistic about their readiness to plan, develop and offer their courses, although some expressed their dissatisfaction with access to quality support from IT or instructional designers/technologists for their courses.

As in Consortium I, the faculty members in Consortium II used an amazing variety of online tools for teaching. Institutional LMS platforms such as Blackboard, Canvas, and Moodle are common among participating institutions. Specialized tools frequently mentioned include BlueJean, Zoom, Voicethread, Dipity, ThinkLink, and Digication, as well as commonly used commercial platforms such as Skype, Spotify, WordPress, YouTube, and Twitter. Many instructors used Google applications for collaborative student work and generally found these to work well. Faculty liked being able to embed online library resources into their course syllabi. Some faculty encountered problems using LMS-based discussion boards and Google Hangout.

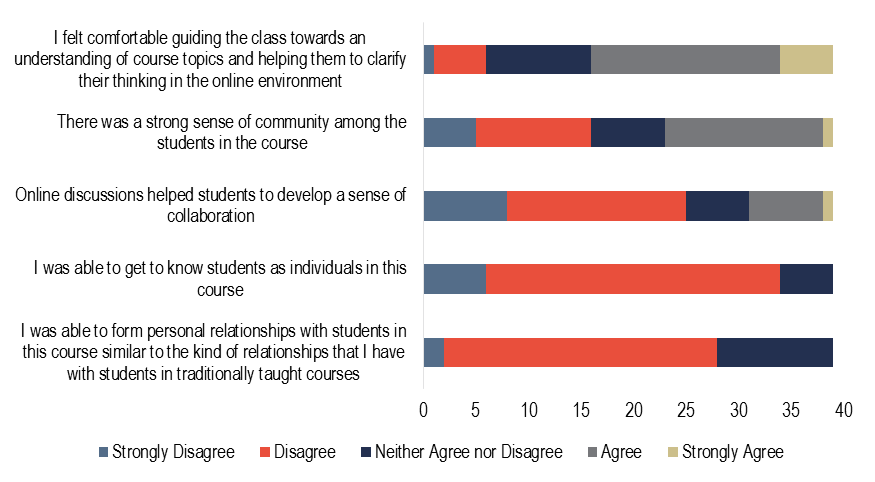

Figure 14: Instructors’ Perceived Social Presence in Consortium Courses

The instructors reported being relatively comfortable guiding students toward an understanding of the course topics and helping them to clarify their thinking in the online environment. The instructors reported mixed feelings about the online environment helping to create a sense of community among students—and they were quite negative about online discussions as a way to develop a sense of collaboration, about getting to know students as individuals, and about forming personal relationships with students similar to the kind of relationships develop in traditionally taught courses.

Table 1: Successful and Not-So-Successful Instructional Strategies

| What instructional approaches worked especially well in the online environment? | What instructional approaches did you find disappointing in the online environment? |

|---|---|

| Using multimedia resources (e.g., websites, videos, images, instructor created voice-over lecture slides) | Using long information-filled videos (which required students a lot of time to watch) |

| Going “paperless” submitting and grading all work online | Giving detailed written feedback on students’ writing online (which often went unused by students) |

| Allowing students to work at their own pace | Assigning group or pair work (which required students to meet face-to-face or online to collaboratively work with others while holding each other accountable for getting their work done) |

| Giving multiple options for required assignments | Assigning longer term projects (without rigidly structured ongoing assignments for students) |

| Structured regular assignments due at regular intervals | Getting key concepts across to the students (since students spent little time to study/review online materials) |

| Using discussion boards for structured online discussions | Using discussion boards for engaging discussions or debate (to achieve particular disciplinary learning outcomes) |

| Incorporating games or other interactive activities using course materials | Incorporating synchronous activities (due to technical difficulties, scheduling and/or student involvement) |

Instructional approaches that were identified by the instructors as having worked especially well in the online environment included those that afforded students more flexibility (e.g., allowing students to work at their own pace, giving multiple options for required assignments, submitting all work online) and those that enhanced the quality of instructional materials by incorporating multimedia resources, games, or other interactive activities. Having clear organizational structures for assignments and online discussions also proved to be effective instructional approaches in the online environment.

Instructional approaches that the instructors found to be disappointing included those that required a lot of the students’ time and sustained engagement. Some instructors noted that a lot of the detailed written feedback on student writing they delivered online, such as typed comments and annotations, often went unused by the students to make improvements on their future assignments. Also, because some students did not spend enough time to study and carefully review the course materials online, some instructors noted that the challenge of getting across the key concepts to the students was greater in the online environment than in the comparable face-to-face environment.

Student Experience

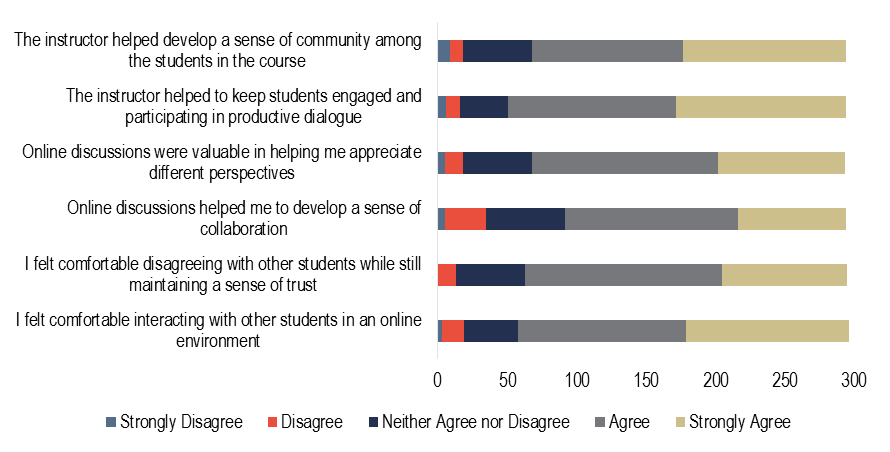

Figure 15: Students’ Perceived Social Presence in Consortium Courses

Students rated the level of social presence in their courses very highly. Many students felt comfortable interacting with other students online, disagreeing with others’ viewpoints while maintaining a sense of trust, and developing a sense of collaboration. They also rated highly the online discussions in helping them appreciate different perspectives as well as the instructors’ role in facilitating productive conversations and developing a sense of community among students. These responses offer a sharp contrast to the instructors’ responses to a similar set of statements about social presence.

Students rated the level of social presence in their courses very highly. Many students felt comfortable interacting with other students online, disagreeing with others’ viewpoints while maintaining a sense of trust, and developing a sense of collaboration. They also rated highly the online discussions in helping them appreciate different perspectives as well as the instructors’ role in facilitating productive conversations and developing a sense of community among students. These responses offer a sharp contrast to the instructors’ responses to a similar set of statements about social presence.

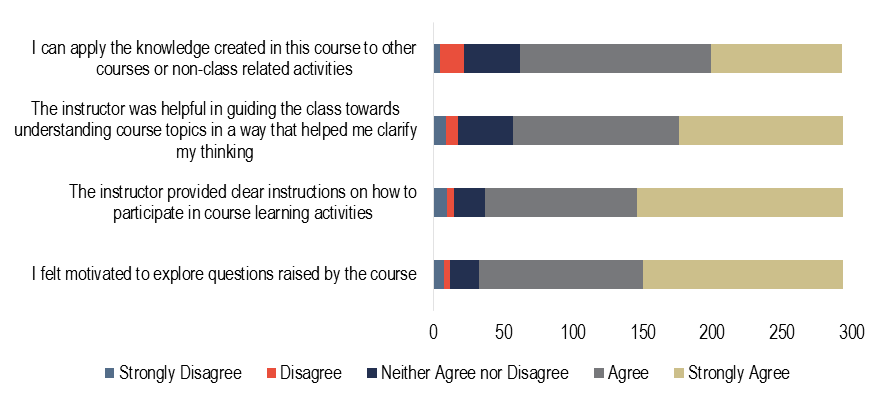

Figure 16: Students’ Perception of Cognitive and Instructor Presences in Consortium Courses

Many students also rated highly their learning experience in Consortium courses. Many indicated that they felt motivated to explore questions raised by the course, and rated highly the instructor’s role in providing clear instructions on how to participate in course learning activities while providing guidance towards understanding course topics in ways that clarified their thinking. Many students also responded positively to the question about the transferability of the knowledge gained in these online/hybrid courses to other related activities (including activities outside of the classroom).

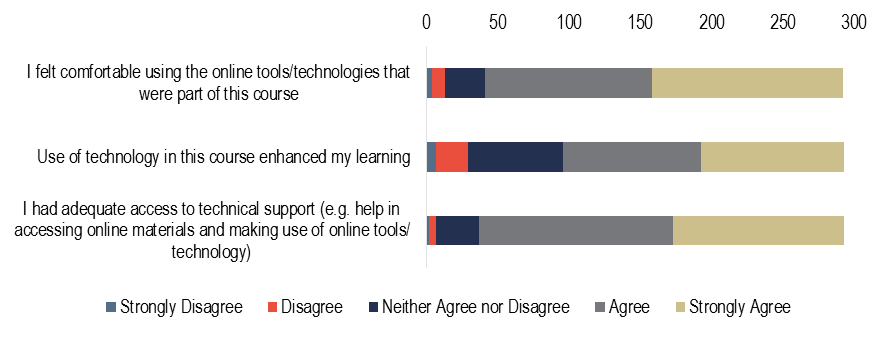

Figure 17: Students’ Experience with Technology in Spring 2017

Although there were some mixed feelings about the use of technology to enhance their learning, the students, for the most part, were comfortable using online tools/technologies that were part of their courses, and felt that they had adequate access to technical support throughout the semester.

Figure 18: Comparing the Consortium Courses to Traditional In-Person Courses (Students)

About 45% of student respondents indicated that the online/hybrid courses offered through the Consortium in Spring 2017 were somewhat better or much better than traditional in-person courses, while 31% thought they were about the same and 25% thought they were somewhat worse or much worse.

Those who responded favorably to the Consortium courses listed the convenience of fitting them into their schedules and participating in the courses at their own pace as the top reasons for their positive responses. One student wrote:

With the course being online, it was much easier to fit other classes I needed to take into my schedule. I find online classes to sometimes be easier to take than traditional classes for this reason.

Another wrote:

I liked that on the Wednesdays we were online I had a choice of when to do the coursework for the day. It gave me time during the morning to prepare for other classes that I wouldn’t have had if we were always in the classroom.

One student noted the convenience of working independently on course materials at home before drafting something to share with classmates online. This student also appreciated the instructor’s role in keeping the course organized, so there were “no surprises”:

I had enough time to get everything done and never felt rushed. I also appreciated not spending time in class discussing, because it was easier to read the material, then write exactly what I wanted to say in forums online. Plus, the professor was very helpful keeping everything organized. There were no surprises.

Those who responded not-so-favorably to this question listed the difficulty of keeping up with a lot of details independently as one of their main challenges. One student wrote:

I feel the course was a lot of work for not actually having someone to keep us on the same page. I think the course was done fine [sic]. There was a lot of detail about assignments and was sufficient for my learning, but I felt the online aspect makes it hard to connect with a class and ask for help.

Another wrote:

I feel like I would have learned the same information in class, but it was A LOT of new information and it was stressful. I did not want to pick worse because it sounded terrible. It was a little more stressful learning this type of material online.

And another wrote:

While I found this online course to be much different from an in-person course, I feel that I learned about the same amount as I would have in a traditional course. The online course required a lot more independent learning, something that I would have made less of an effort to do in an in-person class.

Bringing multiple people together to work on a group project is not always easy, whether in a face-to-face or an online course. This challenge becomes more intense in the online environment, especially when many students have elected to take the online option for reasons of convenience and flexibility. One student raised this concern by writing:

I only say this is somewhat worse because I believe online classes should remain traditional in that they do not require group projects. I had to do most of the work in my group projects even more so with the online class because a lot of people can choose not to answer emails or just do not work as hard as another person and because it is online, people do not have the same time periods allotted for the class. So it’s very difficult to even get people together for even a call at the same time…

Moreover, the issues of “depth” in online instruction and productive discussions were raised by some students, who noted that this particular delivery method might not be appropriate for certain courses. One student wrote:

I feel that for any type of literature course, discussion should occur in person. I feel like although my instructor was absolutely amazing, we were not able to really delve into things because there was only one day a week we actually met. Online courses work great for many disciplines. English is not one of them.

Another student wrote:

Going into greater depth was lost in the annotation assignments. Political biases rather than the placement of political ideology and how they relate to the given philosopher became an issue. I felt like this was something that would not occur had it been an in class discussion.

One student in a philosophy course noted that the lack of instructor lectures in the online environment contributed to her/his lack of understanding of the course content:

The professor was amazing and has an incredible ability to lecture. This was a main reason I signed up for the course. But because the philosophy class was higher level and contained content that was difficult to grasp, I felt as though my understanding of the course content suffered because of the lack of multiple lectures…

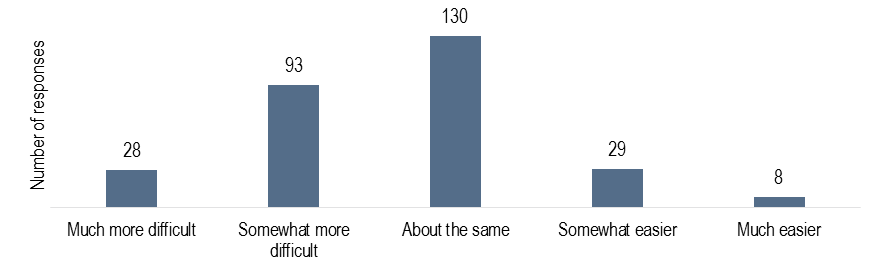

Figure 19: Comparing Consortium Courses to Other Humanities Courses (Students)

In terms of the difficulty of the Consortium courses compared to other upper-level humanities courses, 45% of students indicated that the difficulty level was about the same while another 32% said that that the Consortium course was at least somewhat more difficult and 10% indicated that it was much more difficult.

Student Learning Outcomes

Figure 20: Grade Distribution across Consortium Courses (20 Institutions)

Note: The following letter grades have been excluded from the graph: P, S, I, W, AB, BC, CD.

The grade distribution across Spring 2017’s Consortium courses in 19 institutions revealed that over 80% of students passed their courses (i.e., A’s, B’s, C’s, Pass, Satisfactory) with about 55% of those students having earned A’s (i.e., A+, A, A-). We do not have access to the grade distribution for comparable face-to-face courses during the same semester.

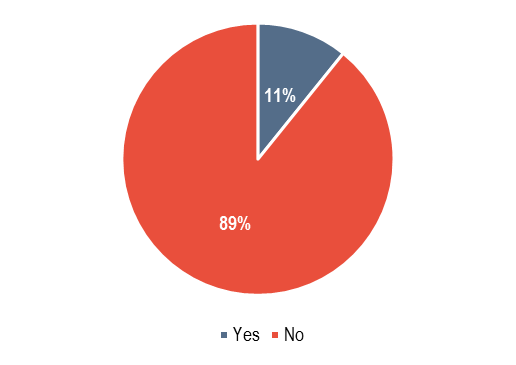

Figure 21: Student Withdrawal Rate in Consortium Courses

Based on the data reported from 20 institutions (n=546 students), the student withdrawal rate across the Consortium courses was about 11%; most of the students who enrolled in the courses remained enrolled throughout the Spring 2017 term. Anecdotally, participants in the August 2017 workshop said that this rate was comparable or perhaps better than the completion rates for comparable face-to-face humanities courses at their institutions.

Course-Specific Learning Outcome Scores by Instructors

A total of 38 instructors, representing 20 Consortium institutions, provided learning outcomes assessment scores for their students. Each instructor identified between two and nine specific learning outcomes per course and assessed each of the students’ achievements on a four-point scale (i.e., Beginning, Developing, Competent, and Accomplished). The average score of learning outcome assessments by the instructors was 2.96, which indicates that the instructors believe their students became “competent” in the core learning outcomes that were identified.

General Learning Outcome Scores by Peer Evaluators

A panel of six faculty evaluators from the cohort used the same four-point scale (i.e., Beginning, Developing, Competent, and Accomplished) to assess student learning outcomes independently. They reviewed a total of 63 student artifacts submitted by 15 instructors to assess whether the students had achieved two learning outcomes that were identified to be the general goals of humanities disciplines: (1) interpreting and analyzing texts and (2) synthesizing knowledge. The average assessment score was 2.66 (somewhere between Developing and Competent), which is slightly lower than that of the instructors’ own learning outcome scores. The average standard deviation for both outcomes were 0.66 and 0.68, respectively which means that the faculty evaluators were fairly in agreement with each other in terms of their assessments of quality of student work in other Consortium courses.

Overall Assessment

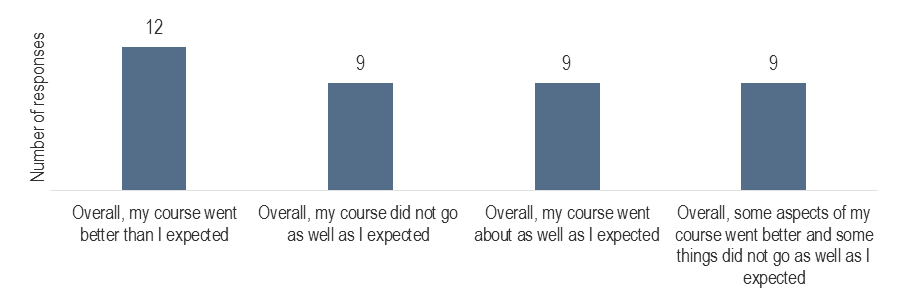

Figure 22: Instructors’ Overall Assessment of the First Iteration of Courses

The instructors had a mixed response to the survey question about their overall assessment of the first iteration of courses. More than half (54%) indicated that their course went about as well as they expected or better than they expected. Those who responded positively to this question explained that having relatively mature and high-performing students in their classes (sometimes hand-picked from the ranks of their previous students) who were able to meet the challenges of online learning, contributed a great deal to their overall assessment of the courses. One instructor wrote:

I thought it was great, but I only had 7 students, they were almost all high-performing majors/seniors, and were those well-equipped (intellectually and organizationally) to live up to the challenge. I thought their writing was better than in a F2F class, and I felt their contributions to the discussion board were substantial and engaging, for the most part. They responded quickly to my emails and queries via Canvas, and I also modified some dates and assignments as I went along in response to requests from them. It was a low-stress experience—easier than F2F in my opinion. However, since I only had students from my own university and I know all of them, this may vary wildly next semester.

Another instructor was generally happy with how the course turned out, although she/he missed being able to engage in discussions with students in person:

I think it went okay. I was lucky to have a lot of very good students, many of whom had classes with me before. I really love this subject, and it was hard to not being able to talk about it in person. I felt disconnected from the conversations I read later to grade.

Among the challenges shared by the instructors, those pertaining to the lack of student engagement really stood out. One instructor wrote:

Mostly, I think, I probably expected more from the students than they were willing to put forth in an elective. When I taught this class face-to-face, students had much more access to me and my help. And, even though I offered the same level of help to these students, I think that doing such things over the computer is just not the same. I tried to set up meetings via Skype, but my students told me that they did not have it; I asked our IT people here to give me some other pointers about what I could do to have interactive online meetings and I never received a response…

Another instructor had a chance to think deeply about the issues of student engagement while reflecting on her/his teaching experience both in online and face-to-face contexts. The instructor wrote:

I keep comparing the student learning to what I remember from the face-to-face version of the same course. Some were able to avoid learning anything here, and my general impression was that it was harder for them to avoid doing the reading, but easier for them to just not engage. Then I looked more carefully at the F2F class. Were they really more engaged, or am I just able to control the class well enough to delude myself that they are more engaged? Are they coming up with the cool insights, or am I just feeding them to them?

Figure 23: Appropriateness of Online/Hybrid Format for Advanced Humanities Content

Over 80% of instructors rated the online/hybrid instructional format to be at least somewhat appropriate for teaching advanced humanities content. Although “appropriate” does not necessarily mean “better” (or even “as good”), the instructors were generally positive about the advantages of the online/hybrid format in not only affording students flexibility and convenience, but also in helping the instructors reimagine course structures to enhance student learning. One instructor wrote:

I think the online/hybrid format has clear advantages in the convenience/flexibility it offers to students, and in the model I used, it did allow me to shift lecture material online (via videos) and thus devoting more class time to discussion. I do not think switching to an online format substantially altered the quality of the students’ work or my grading in either a positive or negative way…

Another instructor wrote:

It’s appropriate but online is not better than F2F, although it is different and it requires a different set of training and tools and a different kind of preparation. The benefits and drawbacks are also different. I do think teaching online works particularly well for a facilitation model in which you want every student to contribute. Making sure that all students contribute in a F2F seminar of 15 can be difficult but it was much easier in the online environment. The discussions, however, were not quite as robust in the F2F model because the asynchronicity made it more difficult to go back and forth more than a few times.

Some instructors situated their responses specific to their course content, and how the online/hybrid format of the course had its advantages in meeting distinctive goals of the humanities. One art history instructor wrote:

In terms of the art history content, students were able to experience a broad range of new approaches to the study of Greek and Roman art. In terms of the political, historical, and cultural contexts students were able to take the time needed to grasp ideas from different perspectives. The requirements of the discussion fora compelled students to have input on every topic. The study of the humanities is essential for a liberal arts education, and the online format makes it accessible to more students, especially those with full time jobs and families. Many students took the course because it fulfilled a general education requirement and even started by thinking they would not like the content and would not learn anything. By the middle of the course, these students had developed a great appreciation for Greek and Roman art and how the basic styles and cultures relate to life today. This is the essence of what we try to achieve in the humanities.

Another instructor in drama wrote:

I teach drama. So I did miss the face to face aspect of the course. BUT, the study of drama does lend itself to an online HUM course because digital projects are ephemeral, live, performative and there is also the affordance of digital production (video, visual, sound etc.) that connect well with the study of drama…

Any efforts to try out a broad range of new and creative approaches in their teaching of advanced humanities content, however, must be backed up with adequate support from an instructor’s institution in order to be successful. One instructor wrote:

I think it can be done well. However, we are not given a whole lot of administrative support. Administrators are clueless as to how much more time-intensive it is to create an engaging online class. In my experience, the most satisfying online classes for students are those that are already front-loaded with all elements ready to go at the students’ own pace. I wasn’t able to do that for this course. Everything is ready by Monday morning (putting in 8–10 hours just on the weekend to create course digital material), but I know students would like to have material available over the weekend.

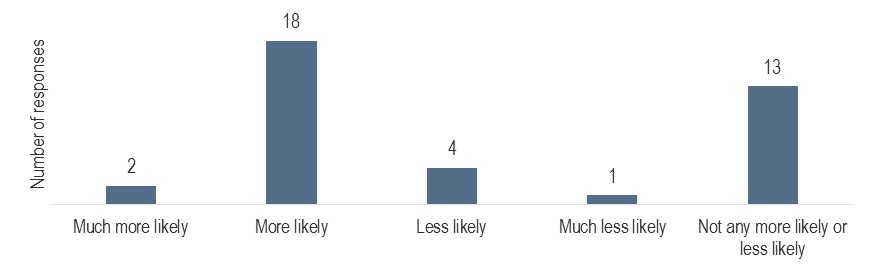

Figure 24: Instructors’ Likelihood of Encouraging Colleagues to Teach Online

About 47% of instructors indicated that they are more likely to encourage their colleagues to teach online as a result of their experience with the first iteration of the consortium courses, although another significant portion of the instructors (34%) indicated that they are “not any more likely or less likely” to encourage their colleagues.

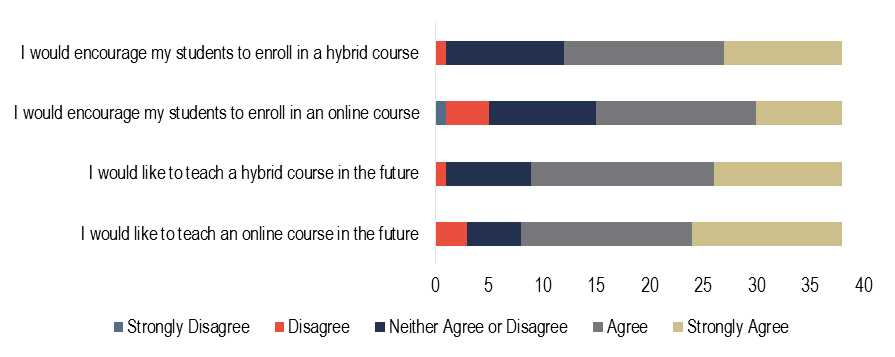

Figure 25: Encouraging Students to Take Online/Hybrid Courses and Teaching Online/Hybrid Courses in the Future

The instructors indicated that they would encourage students to enroll in a online/hybrid course and that they would be interested in teaching another online/hybrid course in the future.

One instructor noted that participation in the CIC Consortium challenged many of her/his assumptions about teaching and learning, and forced her/him to be more conscious about what she/he intends to accomplish in a course as well as the set of expectations that students may bring into the classroom (virtual or face-to-face):

Perhaps the biggest lesson is simply the mindset of the shift from the face to face classroom to the virtual classroom that everything that I want to do in this course is present to the student only in what they experience when they enter the class on their computers. The assumptions that I often employ in the traditional classroom setting cannot be assumed here. More than ever, I have to remind myself to enter the mind of the students and try to think of what they experience when they enter this virtual classroom. In that sense, another lesson is what it can also teach me about my assumptions in the traditional classroom. The online course has helped to challenge assumptions I’ve employed, assumptions that are not necessarily things I should assume. In other words, it has challenged my entire pedagogical approach to teaching—period. It has forced me to become less mechanical and more deliberately conscious of what I’m trying to accomplish…

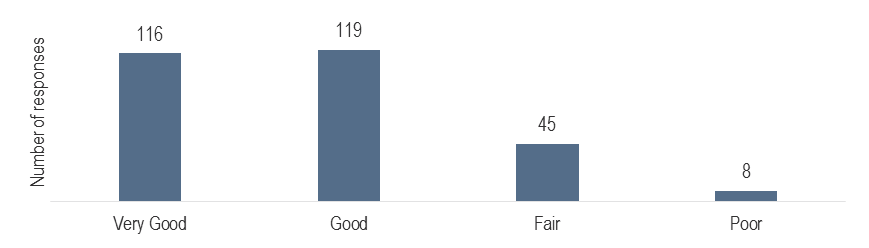

Figure 26: Students’ Overall Evaluation of the Experience with the Course

Students rated their overall experience with the courses very positively, with over 80% of respondents indicating that their experience was either good or very good.

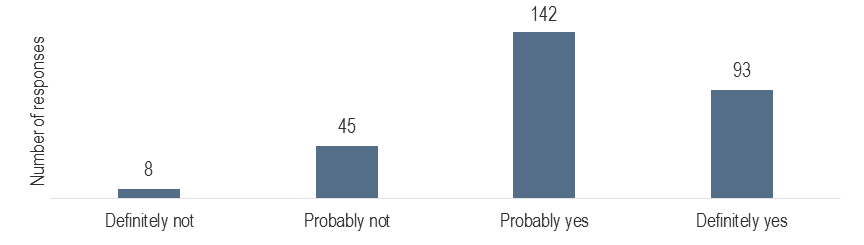

Figure 27: Students’ Likelihood of Taking another Online/Hybrid Course

Also, when asked about their likelihood of taking another online/hybrid course in the future, over 80% of students indicated that they probably or definitely would. The main reasons underlying their positive reactions were, again, largely related to the degree of flexibility that online/hybrid format affords them, as well as supporting their individual learning in meaningful ways. Below are some select student responses along these lines:

Online classes offer more flexible schedules, and I don’t have to worry about missing classes due to unavoidable circumstances.

I liked that I could fit this course into my schedule no matter what was going on. I love traditional, in-class courses, but this one showed me that an online course taught well can be meaningful.

Because I feel like I can be more engaged and absorb more information when I can have the time to sit down and actively participate rather than sit in a classroom at a designated time.

It was a very enjoyable experience, and proved to be a very effective way of learning this specific type of material. The assignments that we did because of the online environment actually helped me learn the material better and more in depth.

Stakeholder Interviews

In addition to the quantitative data, the research team contacted a sampling of instructors, administrators, and registrars and asked them to expand upon their experiences in the Consortium. Through telephone interviews with 10 individuals, we heard mostly enthusiastic and positive comments. Without exception, the interviewees were pleased that their institutions had the opportunity to participate in the project.

Administrators spoke of the importance of the experiment with online courses in the humanities for their institution’s strategic planning. One administrator commented:

One of the goals in our strategic plan is to grow online programs to reach diverse students. Another strategic goal is to raise the profile of our academic programs. This project allows us to reach those goals.

Another administrator commented on the importance of this project to help educate other faculty on campus:

We have a lot of hesitant faculty. We need to let other faculty know about what we have learned. This project has given us tools and resources we would not have otherwise had and we have learned a lot about the benefits of online learning. We need to share that knowledge.

Faculty described the benefits, as well as the challenges, of the project. Several of the instructors commented on how surprised they were to enjoy online teaching. One instructor said:

I had a really positive teaching experience. I was pleasantly surprised by the impact of the teaching experience. I found the benefits of the online tools to be quite good. Now, I need to scale this experience to a larger course.

Another commented:

I tell my skeptical colleagues that the engagement in the course was outstanding—better than in my traditional classroom. Every week, I had more thoughtful and more in depth responses from my students than I see in traditional classes. My students loved the course and talked about how they were engaged.

One instructor looked ahead to the second year and noted:

I am really looking forward to having students from other institutions in my course. It will provide greater diversity in the classroom. Most of our students come from a 100-120-mile radius. Experience from other ethnic and cultural backgrounds would greatly enhance the discussions we have. It will be good for our students—and it will be good for me.

A registrar noted the importance of this project in understanding and meeting the needs of non-traditional students:

Over time, we found that a lot of students are working full time, so the idea of a traditional student has gone away. We want to move all of our students toward degree completion by giving them much more flexibility. That includes more online classes and greater options. This project is a good example of what we want to offer.

Preparing for the Next Iteration of Courses

When asked to describe what they plan to do differently when the courses are offered for a second time in 2017–2018, the instructors had a lot to share. A common thread that cut across nearly all their comments was a commitment to enhancing the student experience and learning in deep and meaningful ways. Below is a summary of instructors’ plans for the next iteration of courses:

Find all possible ways to “humanize” the interaction with students to enhance their learning experience and satisfaction with online instruction

- Create new tactics for promoting regular, synchronous engagement (e.g., incorporate virtual class meetings and office hours).

- Spend more time in the beginning to learn about the students and their learning styles.

- Provide opportunities for students to learn more about and from each other, so they can develop intellectual relationships with their classmates.

Find all possible ways of enhancing student learning

- Provide more detailed rubrics for discussion boards and experiment with different kinds of discussion questions and methods of responding to online posts.

- Drop certain assignments and/or fundamentally change the way certain assignments work.

- Employ other approaches to evaluating student assignments (especially longer-term projects or papers).

- “Front-load” the materials so students can have the flexibility of working at their own pace.

- Incorporate course materials that are both accessible and challenging to meet the needs of students at different developmental levels.

- Provide more online instruction to model the kinds of critical thinking, reading and writing that are expected of students.

- Seek assistance from on-campus services to produce high-quality online course materials.

Conclusion

Our assessment of the first round of online courses offered through Consortium II is generally positive. Students and faculty alike reported that the online courses were equal to or better than traditional face-to-face courses. Even though there were concerns about the loss of personal interaction between instructors and students, small independent colleges have an opportunity with online courses to make more course offerings available to their students without increasing their costs. Faculty have generally found developing online courses to be an opportunity to grow professionally. Many mentioned that the act of creating online courses helped them to become better teachers. The infrastructure needed to support online teaching and learning appears to be adequate on most of the Consortium campuses. And students have come to expect online courses for their convenience.

Several administrators and faculty look forward to next year, with hopes that more students from other institutions will enroll in their courses. The challenge for the Consortium is to think more globally about ways in which expanded online course offerings will help students more generally, rather than how a single institution will benefit. For several of the participating institutions, Consortium II is the first in-depth effort to collaborate at the curricular level with other colleges. Collaboration on this scale is not easy to achieve, but the members of the Consortium have made clear their desire to try. Most administrators identify cost containment is an important goal for their institutions. Developing online courses may well add costs initially, but the promise of lowering costs in the future seems realistic if collaboration is embraced.

Appendix A: List of Data Elements Requested

Student-Level Data

For students participating in Consortium courses:

- Unique identifier (student IDs must be anonymous)

- Home Institution

- Student major field of study

- Student minor field of study (if applicable)

- Consortium course name and number

- Student final course grade

- Indicator of whether a student withdrew from the course

- If available, the student’s withdrawal date

- Indicator of whether the course counts towards the student’s major requirements (either core or elective)

Course-Level Data

- For years (2010-11 to 2015-16), number of courses offered in-person at the institution

- For years (2010-11 to 2015-16), number of courses offered online at the institution

- For years (2010-11 to 2015-16), institutional spending on instruction

Appendix B: Rubric for Peer Assessment

CIC Consortium for Online Humanities Instruction Learning Outcomes Assessment Rubric

Outcome 1

| High Level Goal | Beginning:

did not meet the goal |

Developing:

is approaching the goal |

Competent:

met the goal |

Accomplished:

exceeded the goal |

| 1. Interpret meaning as it is expressed in artistic, intellectual, or cultural works | The student

a. does not appropriately use discipline-based terminology, b. does not summarize or describe major points or features of relevant works c. does not articulate similarities or differences in a range of works |

The student

a. attempts to use discipline-based terminology with uneven success, and demonstrates a basic understanding of that terminology. b. summarizes or describes most of the major points or features of relevant works c. articulates some similarities and differences among assigned works |

The student

a. uses discipline-based terminology appropriately and demonstrates a conceptual understanding of that terminology. b. summarizes or describes the major points or features of relevant works, with some reference to a contextualizing disciplinary framework c. articulates important relationships among assigned works |

The student

a. incorporates and demonstrates command of disciplinary concepts and terminology in sophisticated and complex ways b. summarizes or describes the major points or features of relevant works in detail and depth, and articulates their significance within a contextualizing disciplinary framework c. articulates original and insightful relationships within and beyond the assigned works |

Outcome 2

| High Level Goal | Beginning:

did not meet the goal |

Developing:

is approaching the goal |

Competent:

met the goal |

Accomplished:

exceeded the goal |

| 2. Synthesize knowledge and perspectives gained from interpretive analysis (such as the interpretations referred to in goal 1) | The student

a. makes judgments without using clearly defined criteria b. takes a position (perspective, thesis/hypothesis) that is simplistic and obvious c. does not attempt to understand or engage different positions or worldviews |

The student

a. makes judgments using rudimentary criteria that are appropriate to the discipline b. takes a specific position (perspective, thesis/hypothesis) that acknowledges different sides of an issue c. attempts to understand and engage different positions and worldviews |

The student

a. makes judgments using clear criteria based on appropriate disciplinary principles b. takes a specific position (perspective, thesis/hypothesis) that takes into account the complexities of an issue and acknowledges others’ points of view c. understands and engages with different positions and worldviews |

The student

a. makes judgments using elegantly articulated criteria based on a sophisticated and critical engagement with disciplinary principles b. takes a specific position (perspective, thesis/hypothesis) that is imaginative, taking into account the complexities of an issue and engaging others’ points of view. c. engages in sophisticated dialogue with different positions and worldviews |

Appendix C: Instructor Survey

Instructor Survey Instrument

Dear Consortium Colleague,

Thank you for taking the time to complete this survey. All questions in this survey refer to the course you taught this semester as part of CIC’s Consortium for Online Humanities Instruction. While we have pieces of this information from various sources (proposals, interviews, etc.), the survey will ensure that we have comprehensive information about all the participants’ courses and backgrounds. This will enable us to assess the impact of institutional and background factors on your experiences teaching online. We also wish to learn about your experiences and observations as a result of teaching the course.

This survey should take about 30-40 minutes to complete. If you wish to pause while filling out the survey, your work will be saved and you can return to it later. Click on the “Begin Survey” link below to agree to the terms of participation and start the survey.

Terms of participation: Please note that Ithaka S+R uses a third party provider, Qualtrics, to administer the survey online. Ithaka S+R project staff will have access to participants’ contact information and individual responses, but no individual responses will be reported or published. All results will be reported anonymously and in the aggregate.

1.What is your institutional affiliation?

2. How many years have you been teaching at this institution?

3. What is your primary departmental affiliation?

4. What is the name and number of your course?

5. What is the primary format for your course this semester?

a. My course is entirely online.

b. My course is hybrid.

6. Please select the response that best describes your institution’s experience with online courses:

a. My institution offers a lot of online courses for undergraduates.

b. My institution has offered a small number of online courses for undergraduate students in the past.

c. My institution has only offered online courses for undergraduates during winter and/or summer sessions in the past.

d. My institution has offered online courses in some professional fields, but none designed for undergraduates.

e. My institution has never offered an online course.

7. What is your experience teaching online?

a. I have never taught online before this semester.

b. I have never taught online and my course this semester is not fully online.

c. I have taught 1-2 courses online before this semester.

d. I have taught three or more online courses before this semester.

8. What is your experience teaching hybrid courses (i.e. courses that combine online and face-to-face components)?

a. I have never taught a hybrid course before this semester.

b. I have never taught a hybrid course and my course this semester is not a hybrid.

c. I have taught 1-2 hybrid courses before this semester.

d. I have taught three or more hybrid courses before this semester.

Display Question 9, if selected (b) in Question 5:

9. How much face-to-face class time did your course have?

a. My course had the same amount of class time as a traditional course.

b. My course had 75% or more of the class time of a traditional course.

c. My course had 50-75% of the class time of a traditional course.

d. My course had 25-50% of the class time of a traditional course.

e. My course had 25% or less of the class time of a traditional course.

f. Other (please describe) ____________________

10. Has the course you taught as part of the Consortium been offered before?

a. This course has been offered before as a face-to-face course.

b. This course has been offered before as a hybrid course.

c. This course has been offered before as an online course.

d. This course has never been offered before.

11. What kinds of modifications did you make to your course for this semester?

a. I created a new course from scratch.

b. I modified an existing face-to-face course to make it an online/hybrid course.

c. I enhanced an existing online/hybrid course.

d. Other (please describe) ____________________

12. How does the number of students who enrolled this semester compare to the typical enrollment for a course of this nature at your institution?

a. Fewer students enrolled in this course than typically do for a traditionally taught course of this nature.

b. About the same number of students enrolled in this course.

c. More students enrolled in this course than typically do for a course of this nature.

d. I am not sure.

Your answers to the following questions will help us understand the support you received in planning and developing your course.

13. Did you participate in any kind of training to teach online?

a. Yes

b. No

Display Question 14, if (a) is selected in Question 13:

14. Please describe the training you received before teaching this course. For example, who provided the training? What was the duration in terms of hours or weeks?

15. Did you have access to instructional designers and/or instructional technologists at your institution to help you design and develop your course?

a. Yes

b. No

Display Question 16, if (a) is selected in Question 15:

16. Please estimate how many hours of instructional designer/ instructional technologists’ time you used to plan and develop this course.

17. Did you have access to IT support to design, develop, and/or manage your course?

a. Yes

b. No

Display Question 18, if (a) is selected in Question 17:

18. Please estimate how many hours of IT staff time you used for this course.

19. Please indicate the extent to which you agree with each statement.

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| I felt adequately prepared to plan and develop my online/hybrid courses this semester. | |||||

| I felt adequately prepared to offer my online/hybrid course this semester. | |||||

| I had adequate access to support from instructional designers and/or instructional technologists for this course. | |||||

| I had adequate access to support from IT for this course. | |||||

| I experienced significant technical challenges planning and/or developing my course. | |||||

| I experienced significant technical challenges offering my course. |

20. How much time did it take to plan and develop this course relative to a comparable face-to-face course?

a. Much less time

b. Less time

c. About the same time

d. More time

e. Much more time

21. How much time did it take to teach this course relative to a comparable face-to-face course?

f. Much less time

g. Less time

h. About the same time

i. More time

j. Much more time

Your answers to the following questions will help us understand your impressions of student learning in your course.

22. Please select the statement that best fits your sense of the depth of student learning in this course:

a. The depth of student learning in this course was greater than in most traditionally taught courses.

Tb. he depth of student learning in this course was about the same as in most traditionally taught courses.

c. The depth of student learning in this course was less than in most traditionally taught courses.

23. Please select the statement that best fits your sense of the breadth of student learning in this course:

d. The breadth of student learning in this course was greater than in most traditionally taught courses.

e. The breadth of student learning in this course was about the same as in most traditionally taught courses.

f. The breadth of student learning in this course was less than in most traditionally taught courses.

24. Please indicate the extent to which you agree with each statement.

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| I was able to form personal relationships with students in this course similar to the kind of relationships that I have with students in traditionally taught courses. | |||||

| I was able to get to know students as individuals in this course. | |||||

| Online discussions helped students to develop a sense of collaboration. | |||||

| There was a strong sense of community among the students in the course. | |||||

| I felt comfortable guiding the class towards an understanding of course topics and helping them to clarify their thinking in the online environment. |

25. Please indicate the extent to which you agree with each statement.

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| Students demonstrated a clear understanding of the course structure and expectations. | |||||

| Students felt comfortable interacting with each other in an online environment. | |||||

| Students were able to disagree with each other in the online environment while still maintaining a sense of trust. | |||||

| Students were engaged and participated in productive dialogue in the online environment. | |||||

| Students were motivated to explore questions raised by the course. | |||||

| Students were comfortable using the online tools/technologies that were part of this course. |

Your answers to the following questions will help us understand your experience using technology for course design and delivery.

26. What instructional approaches did you find worked especially well in the online environment?

27. What instructional approaches did you find disappointing in the online environment?

28. What technology tools did you find worked especially well in this course?

29. What technology tools did you find did not work well in this course?

Your answers to the following questions will help us understand your overall impressions of teaching an online or hybrid course.

30. Please select the statement that best fits your situation:

a. Overall, my course went better than I expected.

b. Overall, my course did not go as well as I expected.

c. Overall, my course went about as well as I expected.

d. Overall, some aspects of my course went better and some things did not go as well as I expected.

31. Please explain your answer to the previous question.

32. What did you find most satisfying about teaching in an online/hybrid format?

33. What did you find least satisfying about teaching in an online/hybrid format?

34. What is your overall assessment of whether the online/hybrid format is appropriate for teaching advanced humanities content?

e. Appropriate

f. Somewhat appropriate

g. Not appropriate

h. Too early to tell

35. Please explain your answer to the previous question.

36. What elements or approaches will you change for the second iteration of your course?

37. What were the big lessons or takeaways from the first iteration of your course?

38. Are you more or less likely to encourage your colleagues to teach online as a result of this experience?

i. Much more likely

j. More likely

k. Less likely

l. Much less likely

m. Not any more likely or less likely

39. Based on your experience this term, please indicate the extent to which you agree with the following statements:

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| I would like to teach an online course in the future. | |||||

| I would like to teach a hybrid course in the future. | |||||

| I would encourage my students to enroll in an online course. | |||||

| I would encourage my students to enroll in a hybrid course. |

40. Do you have any additional comments about your course or experience that you would like to share?

Appendix D: Student Survey

Student Survey Instrument

Thank you for taking the time to complete this survey about your experience in Professor _______________’s course this semester. Please note that your responses are confidential and anonymous, and results will only be reported in the aggregate. The survey should take 5-10 minutes to complete.

1.Have you taken one or more online or hybrid courses before this semester?

a. Yes

b. No

2. Rank the three most important reasons you chose to enroll in this course, where 1 is the most important.

______ It fit my schedule.

______ I like to interact with fellow students online.

______ The course is required for my major.

______ I thought it would be easier than a traditional in-person course.

______ I thought I would learn more than in a traditional in-person course.

______ I was curious about online or hybrid courses.

______ The quality/reputation of the instructor attracted me to the course.

______ Other (please explain): __________

3. To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements about the course:

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Agree | Strongly Disagree | |

| I felt comfortable interacting with other students in an online environment | |||||

| I felt comfortable disagreeing with other students while still maintaining a sense of trust. | |||||

| Online discussions helped me to develop a sense of collaboration. | |||||

| Online discussions were valuable in helping me appreciate different perspectives. | |||||

| The instructor helped to keep students engaged and participating in productive dialogue. | |||||

| The instructor helped develop a sense of community among the students in the course. |

4. To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements about the course:

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| I felt motivated to explore questions raised by the course. | |||||

| The instructor provided clear instructions on how to participate in course learning activities. | |||||

| The instructor was helpful in guiding the class towards understanding course topics in a way that helped me clarify my thinking. | |||||

| I can apply the knowledge created in this course to other courses or non-class related activities. |

5. To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements about the course:

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| I felt comfortable using the online tools/technologies that were part of this course. | |||||

| Use of technology in this course enhanced my learning. | |||||

| I had adequate access to technical support (e.g. help in accessing online materials and making use of online tools/ technology). |

6. How would you evaluate your experience in this course?

a. Very Good

b. Good

c. Fair

d. Poor

7. How would you compare this course to a traditional in-person course?

e. Much Worse

f. Somewhat Worse

g. About the Same

h. Somewhat Better

i. Much Better

8. Please explain why you answered the previous question the way you did.

9. How did this course compare to other upper level humanities courses in terms of difficulty?

j. Much more difficult

k. Somewhat more difficult

l. About the same

m. Somewhat easier

n. Much easier

10. Would you take another online or hybrid course?

o. Definitely not

p. Probably not

q. Probably yes

r. Definitely yes

11. Why would you or would you not take another online or hybrid course?

12. What is your class level?

s. First-year

t. Sophomore

u. Junior