Diversity and Inclusion in New York City’s Cultural Sector: BRIC

Efforts towards quantifying the diversity in various industries have gained a great deal of attention in the last few years. From the #OscarsSoWhite controversy,[1] to the initiatives towards transparency in Silicon Valley,[2] to the recent benchmark survey in publishing,[3] quantifying diversity has become a central component of highlighting areas in the workforce that are notably homogenous in order to approach diversity initiatives strategically.

In the summer of 2015, Ithaka S+R administered a survey to over 1,000 cultural organizations in New York City who receive funds from the Department of Cultural Affairs in order to generate a benchmark demographic analysis of the cultural sector. The survey intended to measure the diversity of these organizations’ staff and board members. Eighty-seven percent of these organizations turned in spreadsheets with anonymized records for each employee and board member. In all, the spreadsheets yielded a dataset with 48,000 records. Additionally, 987 organizations (92% rate) responded to a questionnaire which investigated diversity initiatives and barriers. In January 2016, Ithaka S+R released “Diversity in the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs,” a report exploring this data-set and the community’s perceptions of diversity in their own organizations.[4]

The findings in that study were useful insofar as they presented a snapshot of the 2015 demographics on a large scale for cultural organizations in New York. But in some ways this report raised more questions than it answered. What are we to compare these findings to? Which organizations are succeeding in encouraging diversity and inclusion in the workplace? What does that success look like? Certain organizations think hard about diversity, considering part of their mission. What do they observe as the primary barriers to realizing this mission? With the support of the Mertz Gilmore Foundation and the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, Ithaka S+R was able to conduct a study investigating these questions. We hope this resulting study of BRIC offers some context to better understand the macro-level findings on diversity in New York’s cultural sector.

Why BRIC?

The focus of this case study is BRIC,[5] a multi-disciplinary cultural organization located in Fort Greene, Brooklyn. BRIC is a mid-size, gender-balanced, racially diverse organization, whose free-text responses to the DCLA survey questionnaire indicated strong engagement on diversity, equity, and inclusion issues. In late January, President Leslie Schultz, Executive Vice President Betsy Smulyan and Director of Marketing and Communications Binta Vann-Joseph agreed to be interviewed for this study.

What is BRIC House?

Photo Credit: Bailey Constas

BRIC House is the new home for BRIC, an organization that acts as a provider of contemporary art, performing arts, and media programs throughout Brooklyn. BRIC both presents art and video programs and incubates works by local artists and media-makers. BRIC House is located between Fulton and Dekalb avenues, near the historic Fort Greene Park.[6] Many of BRIC’s services and cultural offerings are housed here. For instance, BRIC House is home to Brooklyn Public Access TV. BRIC House is replete with small studios where trained locals come to tell their stories. BRIC offers the training that allows the public to handle media equipment and use technology to hone these stories.

Those studios line the hallways of the second floor of BRIC’s newly designed home,[7] which, after three years of construction, opened in 2013. But the first thing one notices upon arrival is the concrete stoop descending tetris-like into a sunken gallery, home to changing contemporary art exhibitions, surrounded by street level windows. The stoop is a public space. Students from the nearby Brooklyn Technical High School stop in on their lunch breaks. There are tables as well, to type out a report or read a book. A public cafe serves the impeccable lattes that are available in any of the dozens of boutique coffee shops sprawled across the borough. But the lack of pressure to buy one, to enter into a financial transaction in order to secure one’s spot, underscores the public nature of the space. Behind the cafe counter is the current mural “We Be Darker Than Blue,” painted by the artists jetsonorama and Jess X. Chen.[8] These features sit between the building’s entrance and BRIC’s main television studio, from which the New York Emmy nominated BRIC TV airs. Media is half of the organization’s focus; BRIC runs its own 5-channel cable network, manages public access, provides the public with studio space and access to its equipment, and also provides free courses to train the public on how to use equipment and produce media. BRIC has an expertise, wants to share it, and wants it to be free.

However, originally BRIC focused more on the arts than media. Since its inception the arts division of the organization has thrived. Last summer a single program called the BRIC Celebrate Brooklyn! Festival brought close to 200,000 music fans to Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, to listen to free shows in open air for the 37th consecutive year. The festival is the seed that BRIC grew out of when the organization was known as the Fund for the Borough of Brooklyn (FBB); three years later FBB started a contemporary art exhibition program; five years after that FBB was designated the public access provider for Brooklyn by the Borough President and morphed into BRIC shortly thereafter.[9] Since then BRIC has expanded dramatically.

Two years into the newly designed space, BRIC had presented over 400 performing artists and over 400 visual artists. BRIC offers residencies and fellowships for more than two dozen Brooklyn artists each year and also offers dance classes that are open to the community. It sends teaching artists out to more than 30 New York City public schools, from the Bronx to Bensonhurst, but primarily in Brooklyn.[10] BRIC’s mission statement explains that it offers “contemporary art, performing arts, and community media programs that reflect Brooklyn’s creativity and diversity.” This study explores in more depth some of the specific ways BRIC pursues this goal. But it also looks beyond BRIC’s offerings in arts and media, to the people who compose it—to whether the staff bringing these offerings to the community represent the community they serve and how or why that may or may not be the case.

BRIC’s Staff Diversity

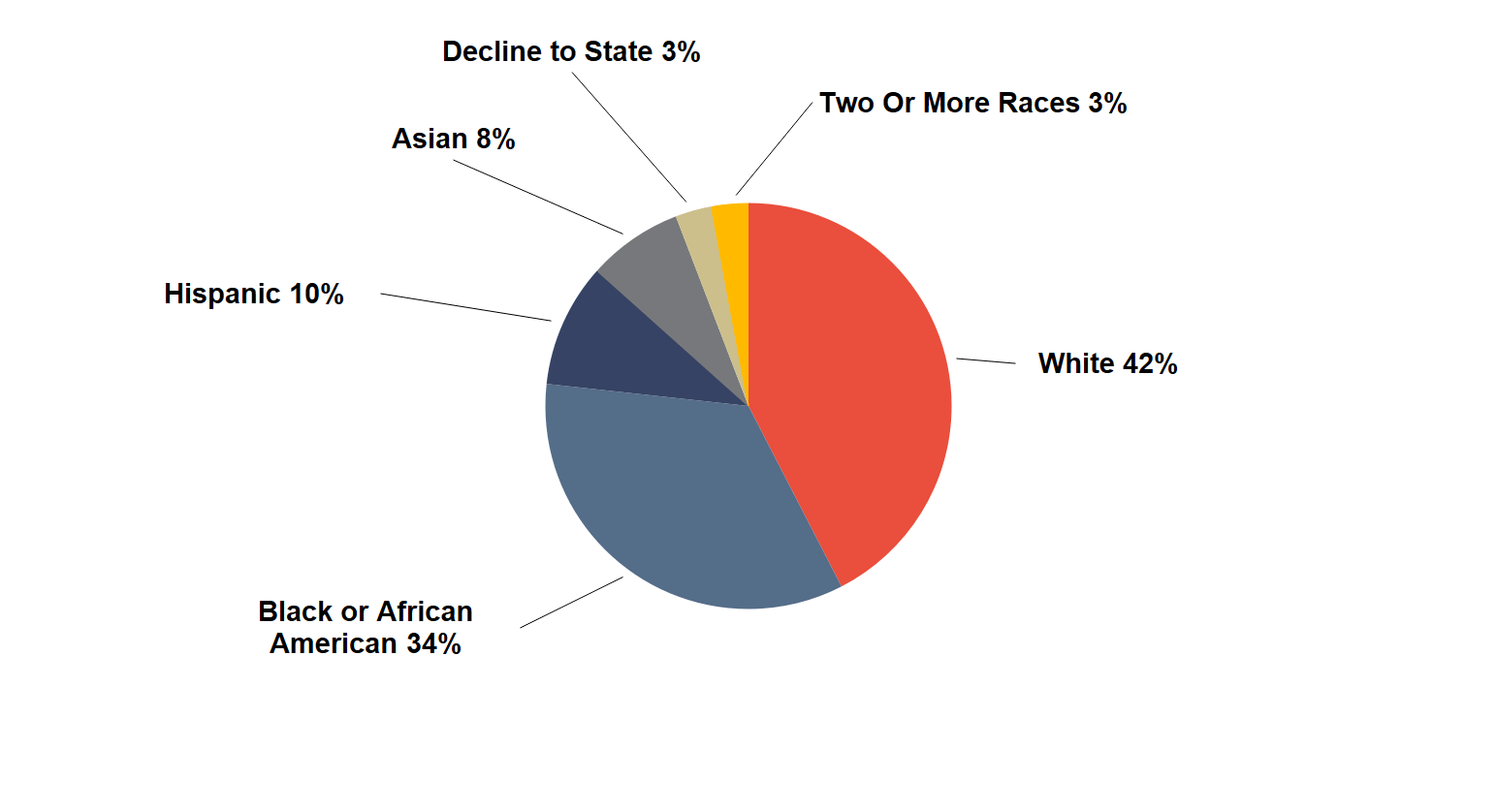

Based on the U.S. Census Bureau 2008-2012 American Community Survey, the 2.6 million residents of Brooklyn are 44.6% white, 34.2% black or African American, 10.6% Asian, and 20% Hispanic. Brooklyn’s black or African American population is 9% higher than in New York City overall, and 21% higher than the national black or African American population. On the whole, the Ithaka S+R survey found that DCLA grantees are 62% white, 15% black or African American, 10% Hispanic and 7% Asian—more diverse than museums nationally,[11] but less diverse than the city as a whole.[12] BRIC reported 172 staff in the survey, 103 of which are full-time. BRIC’s total staff is 34.3% black or African American and 42.4% white.

Figure 1: BRIC Race/Ethnicity Composition

BRIC’s Hispanic population matches that of DCLA grantees at 10%, but is ten percentage points lower than Brooklyn’s Hispanic population.

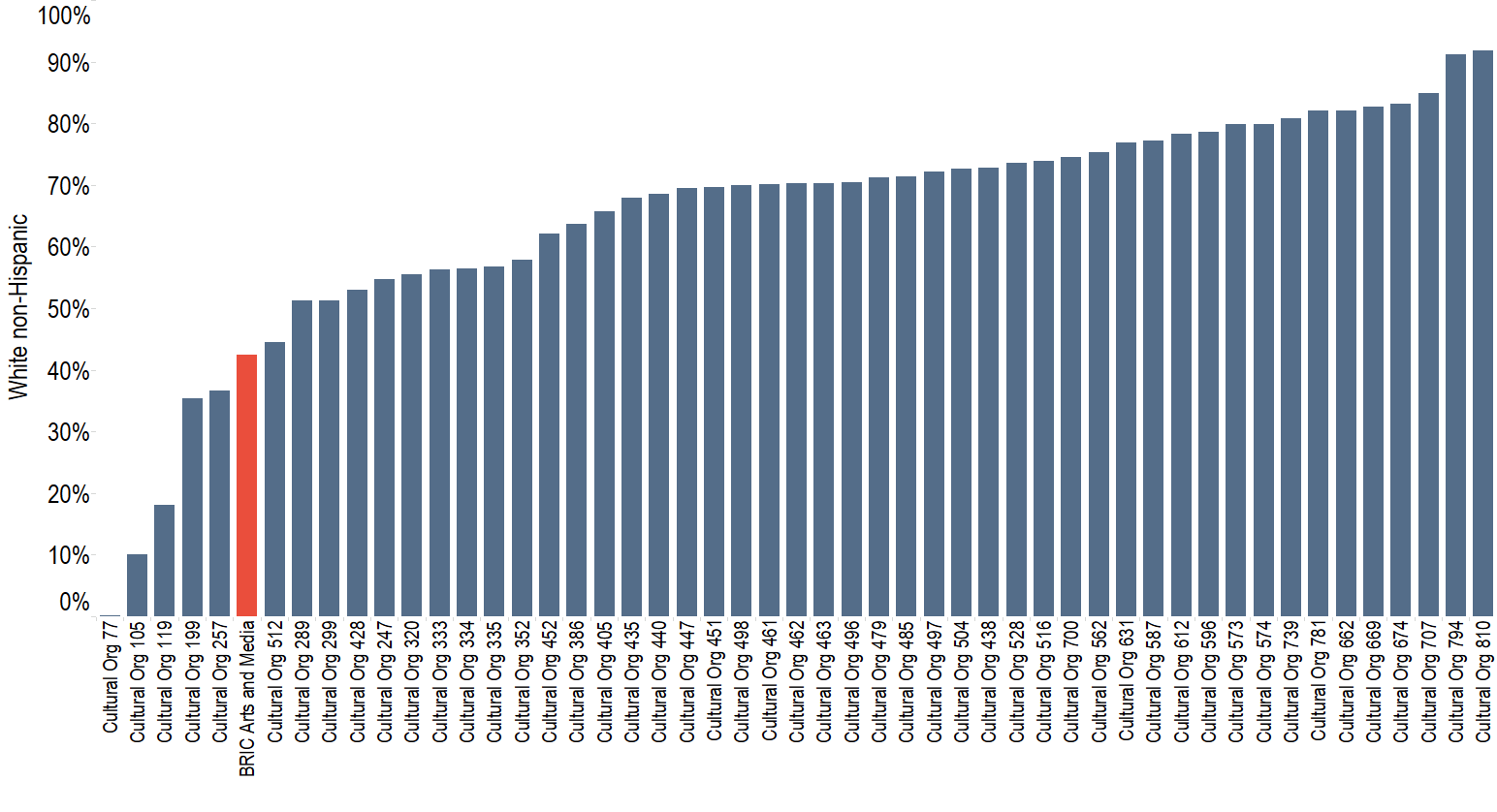

Among its peers in the largest budget category included in the analysis (organizations with budgets of over $10,000,000 annually) BRIC ranked as having the fifth largest proportion of people of color, out of a cohort of over fifty.

Figure 2: Percentage White Non-Hispanic for $10+ Million Organizations

In a county with African American representation nearly three times the national average, BRIC’s staff reflects that community. BRIC reported an even split in staff between men and women. In senior roles, the percentage of female staff increases to 78%, a 28% increase.

Barriers and Initiatives

Initially, President Leslie Schultz expressed hesitancy that BRIC was the right fit for this study. She explained that the organization does not have explicit policies or discrete goals for staff and board diversity. Indeed, the survey results bore that out. In the portion of the survey that focused on barriers to increasing diversity in the organization, BRIC provided free text descriptions for both staff and board members. But when asked about diversity initiatives BRIC noted that it does not have a diversity committee, as 74 DCLA organizations do, or a diversity officer, a position that 39 other DCLA organizations have filled. BRIC also has no recruiting efforts or diversity workshops for staff. Rather, all of its initiatives are primarily oriented around community partnerships and cultural programming. Ultimately, Schultz and Ithaka S+R agreed that the lack of formalized policy around diversity initiatives provided an opportunity to explore the culture and practices of an organization that has maintained a diverse staff organically while tripling in size over the last decade.

Barriers: Staff and Board

BRIC explained in the questionnaire that, “In a few job areas, we often do not get a diverse pool of applicants with the required experience.” Schultz believes, as many in the DCLA grantee community described, that unpaid internships and low-paying entry level positions in the arts in New York make it more likely for the affluent to sustain themselves financially while breaking into a field.[13]

As for barriers to increasing board diversity, BRIC again shared a common observation among respondents that “Segregation in social/work circles skews nominations – people of one race/ethnicity often tend to know people of that same race/ethnicity.” BRIC’s board is more white than its overall staff, but it has twice as many African American and Hispanic board members as DCLA grantees overall.

Figure 3: BRIC Board Race Percentage

Hiring Practices

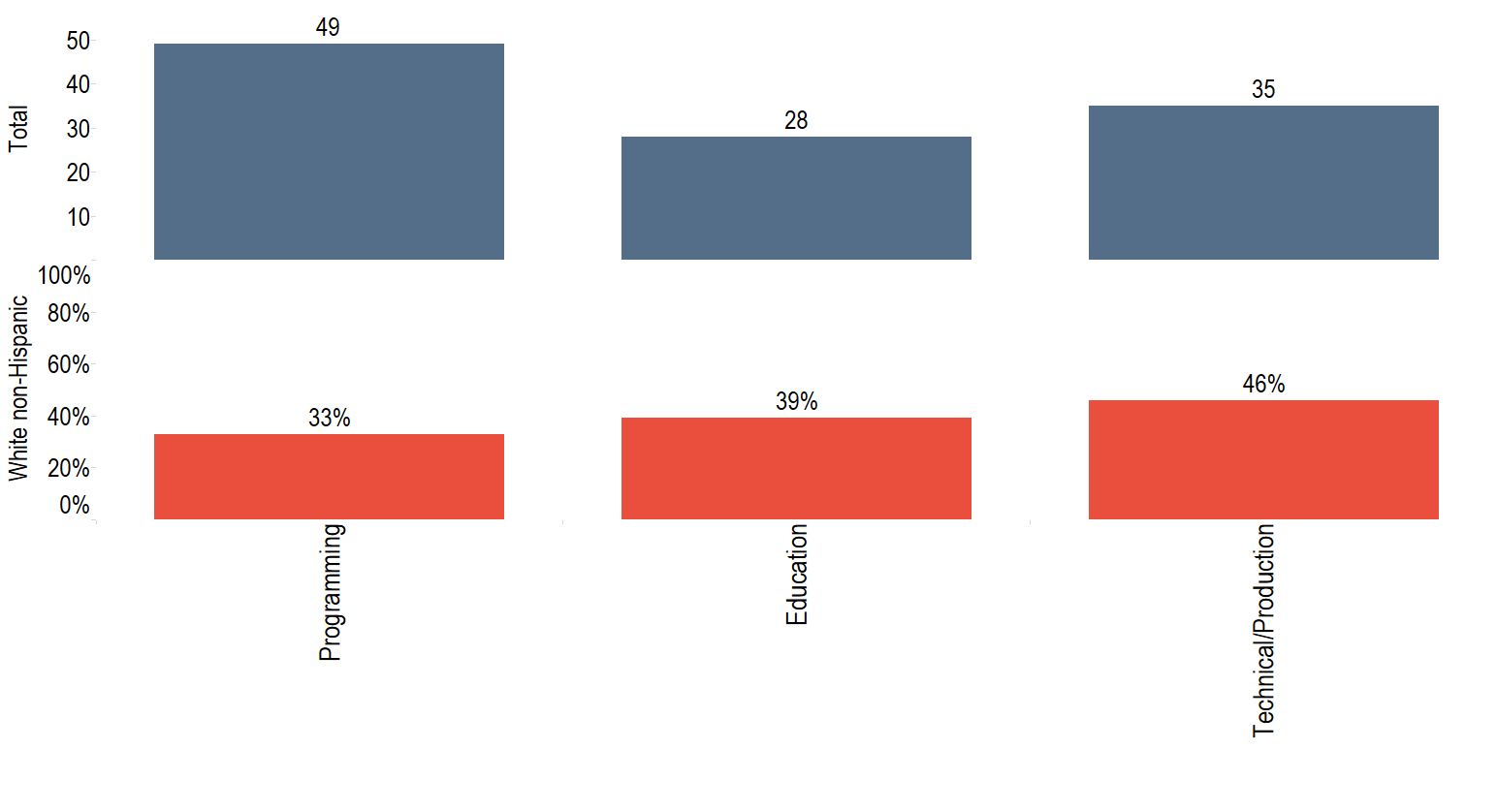

In spite of these barriers, BRIC has been effective in developing a staff that is not only diverse, but also is not segregated by job type. Among museums nationally and DCLA grantees as well, the positions with the highest percent people of color are security and facilities. But for BRIC, diversity spanned across their largest job types: programming, education and technical/production staff.

Figure 4: BRIC Total and Percentage White Non-Hispanic, Large Job Categories

The technical/production staff was especially noteworthy, because for the overall DCLA grantee community technical/production staff had the highest percentage of white non-Hispanic staff among large job categories, 73%. For BRIC the category is 46%.

In September 2015, the DeVos Institute of Arts Management at the University of Maryland published a report titled, “Diversity in the Arts: The Past, Present, and Future of African American and Latino Museums, Dance Companies, and Theater Companies.” The report noted a negative outcome for culturally specific arts organizations as a result of the broader adoption of diversity, inclusion, and equity initiatives in the cultural sector. Their research found that the challenges small, culturally specific organizations faced when applying for funding from individual donors (namely, fewer resources than their mainstream counterparts), were ironically exacerbated:

By mainstream organizations’ efforts to diversify their own programming, drawing funds away from organizations of color. In fact, a study by the NEA in the 1990s found that the second most frequently mentioned concern (after income) was the impact of multiculturalism efforts of mainstream arts organizations on organizations of color.”[14]

In some cases, a prestigious museum might attract talent away from a smaller culturally specific organization as part of an effort to diversify its staff.

BRIC does not appear to engage in this technique. “We operate on a fairly fixed budget, we don’t have much flexibility with our salaries,” Smulyan noted when asked whether BRIC actively competes for people of color in their hiring process. She said BRIC is most interested in hiring staff with a “diverse outlook,” mentioning a recent digital journalist hire, whose Middle-Eastern perspective was appealing. But the journalist seemed to be the exception, as we heard consistently that one thing BRIC was not looking for was a diversity of zip codes, which is to say they like staff to be residents of the borough they serve. Either Smulyan or Schultz meet with every full time employee that BRIC hires. This is increasingly challenging as BRIC has grown to an organization of over 100 employees, but they feel it is an important part of staying connected to the staff.

Vann-Joseph, BRIC’s director of marketing, described her hiring practices as a manager. When she came to BRIC she was told to assess the team she was inheriting and determine whether “They had the right skillsets and felt connected to Brooklyn.” She went on to explain the importance of managing a team that understands the community it serves.

In her hiring process, Vann-Joseph keeps postings up as long as possible, and conducts as many phone interviews as she can, typically around twenty-five. She looks to bring those who pitch themselves well into BRIC for a panel interview, a hiring practice where a candidate interviews with multiple staff members simultaneously. She believes these panel interviews are crucial. She learned the practice from Verizon, her previous employer, who she said was known for having diverse management. “Panel interviews hedge your bets,” expanding that there is less of a chance for innate bias to affect the hiring process in panel interviews.

Vann-Joseph reiterated points made by both Schultz and Smulyan that finding someone who is a good cultural fit with the right skill set is the priority for them: “We have a fantastic team member who emcees drag events in his spare time. If I get even an inkling of homophobia in a candidate there’s no chance. People work hardest when they feel you’ve got their back.”

Initiatives: Programming

BRIC speculates that staff diversity may be an outgrowth of the type of programming it offers. This was also evident in BRIC’s description on the survey questionnaire about community partnerships: “We provide classes and media services in five Brooklyn Public Library neighborhood branches. We partner with Ingersoll Houses for dance classes and engagement with our resident dance company. We work with social justice and social service organizations to build capacity and create media to amplify their work.” BRIC highlighted the spectrum of voices that are amplified by its public access services and featured in BRIC TV interviews. BRIC also noted its awareness of diversity and inclusion when presenting work in the arts: “Presentation of diverse artists; affordability; family programming appealing to a broad demographic, creation of video content about all aspects of life in Brooklyn, to appeal to a broad audience.” To deliver these programs, BRIC has engaged in a number of community partnerships, including with Brooklyn Public Library and Ingersoll Community Center.

Brooklyn Public Library

For the last three years BRIC and Brooklyn Public Library have had a fruitful partnership that has allowed both to expand their impact. Jesse Montero, who has recently taken over as director of the main branch of Brooklyn Public Library (BPL), previously served as director of information services for the library’s digital access and inclusion initiatives. In 2012 he spearheaded an information commons in BPL’s main branch, providing a space in the library for people to work and offering training in certain computer skills, from Microsoft Office to Adobe Premiere editing software. He wanted to expand BPL’s digital literacy offerings, but recognized that BPL needed help: “We were looking for organizations to partner with, trying to get a lay of the land for non-profits in Brooklyn that were aligned,” he said of the early stages of the library’s partnership with BRIC. “BRIC and BPL have an overlapping mission: public information and culture. We’re both interested in digital and media literacy and production. As long as the missions make sense it’s very easy to have a partnership. In this case they did: empowering people through knowledge and information. Culturally it’s been a great fit.”

The partnership has allowed BRIC to offer digital media courses throughout a number of BPL branches, expanding its reach to Brooklynites who can’t easily access the facilities downtown. Schultz described the partnership as an elegant solution; BRIC was looking to expand its reach throughout Brooklyn, and instead of developing new spaces it was able to enrich existing ones. BRIC not only offers classes from these branches, it also allows the equipment to be loaned out—professional-grade studio cameras, audio equipment, and studio lighting. Montero expressed that, besides the aligned mission, it has been an advantageous partnership for staff development. BRIC’s media educators teach the class to the public, but also train the library staff on how to use equipment and instruct others, expanding their expertise. The BPL librarians who help with the classes now have a new skill-set to better serve the public.

The library offers both one-off classes in short-form production for PC or mac, as well as a certification track—18 hours of coursework—that will ultimately result in a certification to use BRIC House studio space and equipment. Since it started three years ago, Montero says the attendance has been high. Nearly 2,000 people have attended orientation classes held at the BPL branches “I think they’re really committed to community engagement,” Montero said of BRIC. “BRIC House is great but they also want to offer classes in Coney Island library. They don’t just want to serve out of the Brooklyn Cultural District. People pay a lot of money for these classes. BRIC offers them free.”

Ingersoll Community Center

BRIC’s partnership with Ingersoll started about three years ago, when Ronald K. Brown, the artistic director of Evidence Dance Company and artist in residence at BRIC, discussed the possibility of offering dance classes that would meet half the time at BRIC and at Ingersoll Community Center the other half. The community center is open to the public but primarily serves the Ingersoll, Whitman, and Farragut public housing complexes. The partnership was the product of BRIC’s a concerted effort to engage and include all residents in its new space. As Fort Greene grows increasingly gentrified,[15] more and more of the newer residents consider the northern boundary of the neighborhood to be Myrtle Ave,[16] excluding the Ingersoll housing community from the neighborhood it historically has been a part of. Median income for the public housing unit is $23,889 compared to $71,754 in the surrounding area, District 2 (Fort Greene, Downtown, Brooklyn Heights, Clinton Hill).[17] BRIC’s inclusion of Ingersoll in its community engagement initiatives contrasts with some of the shifting cultural forces in Brooklyn that have contributed to issues of displacement.[18]

Ronald K. Brown is a native of the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, where his dance company is now located. Besides founding the dance company that is now in the midst of a three year residency at BRIC, he has choreographed for Philadanco, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, and has won a number of awards including a Guggenheim Fellowship and a Bessie Award. He collaborated with Jack Walsh, BRIC’s vice president of the performing arts, to engineer a partnership with the Ingersoll Community Center to offer high quality dance classes for free. The attendees were a mixture of dancers who follow Brown’s work, and residents of the Ingersoll housing community. Vann-Joseph explained to us that this approach to community engagement is deliberate, telling us “You have to disrupt the pattern for the community. You have to get out of your building,” in order to bring people in. The program introduced some Ingersoll residents to the rich cultural center just around the corner from them. Participants were encouraged to attend an open rehearsal for an Evidence performance that would be held at BRIC. In this way the program provided an access point not only to the new space, but also to participate in the artistic production BRIC fosters.

Inclusion

These programs illustrate BRIC’s strategy for community engagement. By meeting the community where they are, the partnerships with Ingersoll Community Center and BPL have made cultural offerings convenient for interested residents in a way that contextualizes the richness of resources at BRIC House. BRIC recognizes that it does not have explicit policies in place that generate the diversity found among its staff. Schultz, Smulyan and Vann-Joseph’s speculation that programming and community engagement may have something to do with their staff demographics can be understood, then, through the lens of inclusion. The work of the organization speaks for itself; it is self-evident that the diversity of the community they serve is celebrated at every level of the organization. The hiring follows.

Inclusion is a term often used liberally, sometimes even interchangeably with diversity. For BRIC, inclusion is an attitude rather than a characteristic. In Diversity at Work: The Practice of Inclusion,[19] Bernardo Ferdman describes an inclusive organization as one where: “The diversity of knowledge and perspectives that members of different groups bring has shaped its strategy, its work, its management and operating systems, and its core values and norms for success; [and where] members of all groups are treated fairly, feel and are included, have equal opportunities, and are represented at all organizational levels and functions.” There is a relationship here: the organization is shaped by the people who compose it, and that shape invites certain kinds of people.

This begs the question: what do we make of quantitative or representational approaches to measuring diversity, inclusion and equity? As Judith Y. Weisinger, Ramón Borges-Méndez, and Carl Milofsky write in their article: “Diversity in the Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector”:

One reason the representational approach is a common focus in organizational diversity efforts is because measuring these aspects can be far easier than measuring or evaluating processes leading to organizational inclusiveness. […] Much criticism of the diversity concept reflects a concern that an overemphasis on representation deflects from what is actually needed to capitalize on the benefits of diversity—that is, new ways of thinking about and carrying out the organization’s mission and its work that fully include the contributions of all organizational members.[20]

Or in Ursula Rucker’s[21] (spoken) words at the BRIC Stoop Series event that celebrated women of color with the unveiling of the “We Be Darker Than Blue” mural: “Ethnic democratic economic geographic / Tell me what’s your demographic I’ll put it on the chart and graph it / Reduce your life to data and statistics, it’s tragic.” While it was a quantitative approach that led Ithaka S+R to interact with BRIC and try to learn more about effective diversity practices, it is far from a quota system that generated the diversity in this organization. Hiring practices are designed to avoid innate bias and if there are no people of color in the application pool Smulyan is likely to ask the hiring manager why. But broadly speaking, as BRIC’s partnerships show, the organization’s work has resulted in an atmosphere of inclusion, and the atmosphere of inclusion has resulted in a diverse staff.

- Tre’vell Anderson, “#OscarsSoWhite Creator on Oscar Noms: ‘Don’t Tell Me That People of Color, Women Cannot Fill Seats,'” Los Angeles Times, January 14, 2016, http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/envelope/la-et-mn-april-reign-oscars-so-white-diversity-20160114-story.html. ↑

- Alba Davey, “Pinterest Points the Way as Silicon Valley Grapples with Diversity,” Wired.com, January 6, 2016, accessed March 03, 2016, http://www.wired.com/2016/01/pinterest-points-the-way-as-silicon-valley-grapples-with-diversity/. ↑

- Justin Low, “Where Is the Diversity in Publishing? The 2015 Diversity Baseline Survey Results,” Lee Low Blog, accessed March 3, 2016, http://blog.leeandlow.com/2016/01/26/where-is-the-diversity-in-publishing-the-2015-diversity-baseline-survey-results/. ↑

- Roger C. Schonfeld and Liam Sweeney, “Diversity in the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs Community,” Ithaka S+R. January 28, 2016, http://sr.ithaka.org?p=276381. ↑

- BRIC originally stood for Brooklyn Information and Culture but now it is no longer used as an acronym. ↑

- “Fort Greene Park,” Highlights: NYC Parks, accessed March 23, 2016, http://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/fort-greene-park/history. ↑

- “” BRIC/UrbanGlass Multidisciplinary Arts Center Brooklyn,” Leeser Architecture, accessed March 3, 2016, http://www.leeser.com/cultural#/strand-1/. ↑

- The mural is viewable online at http://www.bricartsmedia.org/art-exhibitions/cafe-mural-jetsonorama-and-jess-x-chen. For more information about jetsonorama, see http://jetsonorama.net/welcome/. For more information about Jess X. Chen, see http://www.jessxchen.com/ABOUT. ↑

- “Our History,” BRIC, accessed March 3, 2016, http://www.bricartsmedia.org/about/our-history. ↑

- “Annual Reports,” BRIC, accessed March 3, 2016, http://www.bricartsmedia.org/about/our-mission/annual-reports. ↑

- Jennifer Smith, “City Plans Programs to Boost Diversity After Study,” The Wall Street Journal, January 28, 2016, accessed April 8, 2016, http://www.wsj.com/articles/city-plans-programs-to-boost-diversity-after-study-1453957261. ↑

- Robin Pogrebin, “New York Arts Organizations Lack the Diversity of Their City,” The New York Times, January 28, 2016, accessed April 8, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/29/arts/new-york-arts-organizations-lack-the-diversity-of-their-city.html?_r=0. ↑

- Richard V. Reeves, “Downward Social Mobility: The Glass-Floor Problem,” The Brookings Institution, September 29, 2013, accessed March 03, 2016, http://www.brookings.edu/research/opinions/2013/09/29-downward-social-mobility-glass-floor-problem-reeves. ↑

- “DeVos Institute of Arts Management at the Kennedy Center,” Diversity in the Arts, accessed March 25, 2016. http://devosinstitute.umd.edu/What-We-Do/Services-For-Individuals/Research Initiatives/Diversity in the Arts. ↑

- “Brooklyn for Sale: The Price of Gentrification, A Community Town Hall,” Vimeo, accessed March 25, 2016. https://vimeo.com/118135158. ↑

- Rosa Goldensohn, “MAP: Here’s Where You Drew Fort Greene’s Borders,” DNAinfo New York, accessed March 25, 2016, https://www.dnainfo.com/new-york/20150929/fort-greene/map-heres-where-you-drew-fort-greenes-borders. ↑

- The New York City Housing Authority and The New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development, “Affordable Housing for Next Generation NYCHA Sites in the Bronx and Brooklyn: Request for Proposals,” July 1, 2015, http://www.capitalnewyork.com/sites/default/files/NextGen%20RFP_FINAL.PDF. ↑

- “Residents Rally against Exclusion from Plans for Downtown BK,” Furee.org, March 25, 2011, accessed March 3, 2016, http://furee.org/news/inthemedia/residents-rally-against-exclusion-plans-downtown-bk. ↑

- Bernardo M. Ferdman and Barbara Deane, Diversity at Work: The Practice of Inclusion (San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 2014). ↑

- Judith Y. Weisinger, Ramón Borges-Méndez, and Carl Milofsky, “Diversity in the Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector,” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 45, no. 1 (2016), doi:10.1177/0899764015613568. ↑

- “Ursula Rucker, Spoken Word Artist,” accessed March 3, 2016, http://aalbc.com/authors/ursula.htm. ↑

Attribution/NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of the license, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.