Expanding Pathways to College Enrollment and Degree Attainment

Policies and Reforms for a Diverse Population

For states to increase access to and attainment of higher education, they must implement policies and reforms that support learners who have not traditionally been well-served by higher education. By 2020, the United States is projected to have a shortage of five million workers with the adequate postsecondary education to fulfill workforce needs. States have a vested interest in and obligation to create multiple pathways to college enrollment and credential attainment that fit the needs of their diverse populations, not only to increase their attainment rates, but to provide options for those who are currently falling through the cracks of the existing higher education structures.

In this issue brief, we will discuss pathways implemented through state policy, and not through specific institutions or systems, which fall into three main categories: Simplifying Transfer, Reforming Remediation, and Alternative Credentials and Pathways. Each category represents a group of policies that seek to lower barriers to access and completion for historically underserved students. We suggest that if states address these three sets of policies, they will significantly improve access for the increasingly diverse set of college students. At the end of this issue brief, we will pose some guiding questions for future research, focusing on which states are performing well and which methods might be the most promising to pursue.

We gratefully acknowledge the Joyce Foundation for supporting this issue brief.

The Case for Expanding Pathways

In the 21st Century, the image of the “traditional” college student as a recent high school graduate who is enrolled full time at a four-year, residential college is no longer the reality for most.[1] Large numbers of students enroll in community college directly out of high school or enroll in a two- or four-year institution for the first time several years after graduating high school. Moreover, as the economy and technology change the skills required to obtain (or keep) a well-paying job, many working adults find themselves in a position where they need to obtain a postsecondary degree to remain competitive in the labor force. Adult learners can also consist of military veterans, or those who earned some postsecondary credit previously but never completed a certificate or degree.

Over half of undergraduate students have characteristics that distinguish them from the 20th Century norm. The new majority in higher education today consists of students who have received a GED or equivalent, are employed full time while in school, earned their postsecondary credential by attending part-time, were 25 or older when attaining their bachelor’s degree or during their last postsecondary course, are parents or caregivers, or are connected to the military.[2] In fact, 40 percent of students enrolled in the fall of 2016 were 25 and older, and 39 percent of students were enrolled part time.[3] In the 2015-16 academic year, only 16 percent of undergraduate students lived on campus.[4] The “traditional” college student is no longer the typical student. Yet, despite this changing student population, the current higher education system is, in important ways, still grounded in a design intended for students who followed the traditional pathway, often neglecting the unique needs of varied populations that require different supports and program structures to complete their degrees.

The mismatch between program design and the characteristics and needs of the new majority may be one reason for the significant degree completion challenges in higher education. According to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, only 39.4 percent of students graduate from a two-year public institution within six years, compared to 67.8 percent of traditional students at four-year institutions.[5] Furthermore, only 43.5 percent of adult learners graduate within six years at four-year institutions. [6]

Part of the shortfall in completions is a result of the large share of students who transfer to another institution before completing their program. In fact, 64 percent of students completing a bachelor’s degree attend multiple institutions during their studies.[7] Unfortunately, the transfer process is far from seamless. In a study conducted by the Community College Research Center at Columbia’s Teachers College, 80 percent of the more than one million students starting community college in fall 2007 were deemed “bachelor’s degree-seeking,” yet only 14 percent of them went on to earn a bachelor’s degree within six years.[8] One of the main factors in this attrition is the loss of college credits during transfer. Community college transfer students who have at least 90 percent of their credits transferred are 2.5 times more likely to graduate compared to those who had less than half of their credits transfer.[9] Yet 43 percent of all transfer credits are not counted by the receiving institution.[10]

Implementing reforms that support the new majority of college students (who are often community college students) is a key to increasing attainment rates in states and developing a skilled workforce in an increasingly educated and competitive global market. These reforms simultaneously will provide a solid infrastructure to students who are often the most disadvantaged and unsupported throughout the postsecondary system. We now turn to a discussion of three categories of policies the research indicates as promising opportunities for improving access and attainment for the new majority: Simplifying Transfer, Reforming Remediation, and Alternative Credentials and Pathways. By addressing these issues, state policymakers can minimize some of the most substantial barriers facing the new majority of students.

Simplifying Transfer

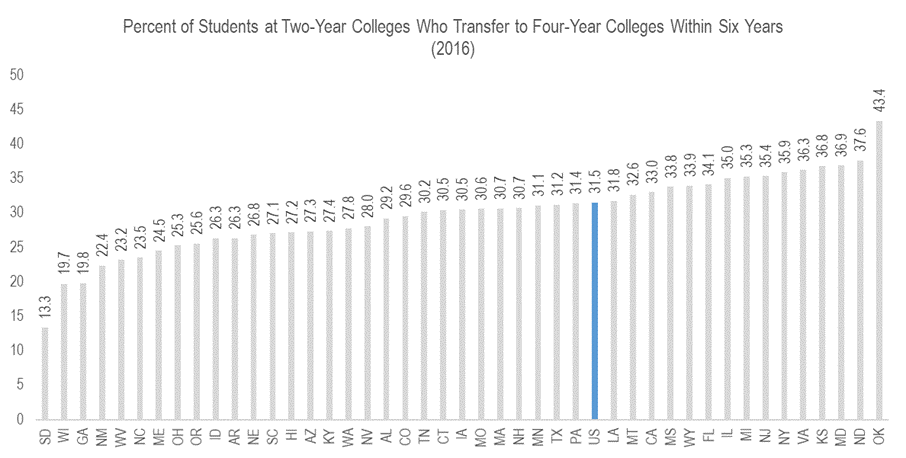

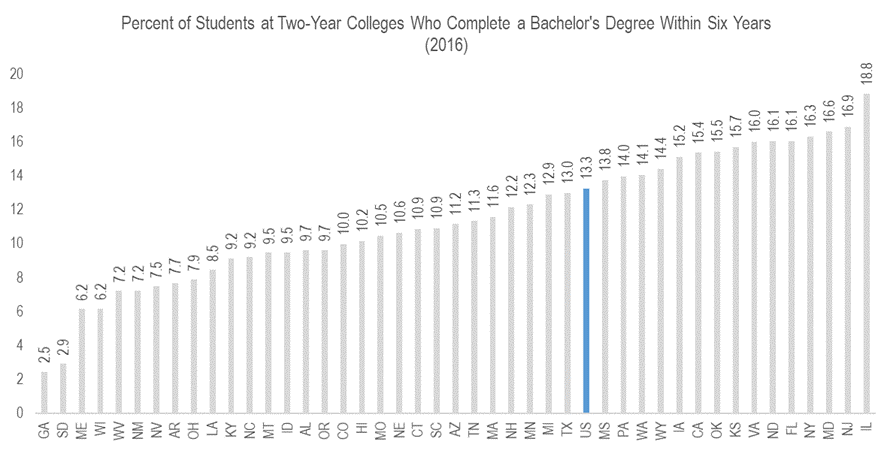

Fewer than a third of community college students transfer to a four-year college within six years of their initial enrollment, as shown in Figure 1. While the transfer rate in most states is similar to the national average, there are a few states – most notably, Oklahoma – that have marginally better results and may merit further exploration into potential best practices. More troubling is that only 13 percent of students who started at a community college went on to earn a bachelor’s degree within six years. That includes a 42 percent bachelor’s degree attainment rate of 2010 students who transferred to a four-year college.

Figure 1 – Nationally, 32 percent of students at two-year colleges transfer to a four-year college within six years and 13 percent earn a bachelor’s degree

Source: National Student Clearinghouse. Note: Alaska, Delaware, Indiana, Rhode Island, Utah, and Vermont are excluded because the NSC does not calculate a transfer rate for these states. |

There are a variety of state transfer policies designed to improve transfer student access and success.[11] Here, we focus on a subset of those policies that emphasize two design principles. First, these policies consider multi-directional transfer pathways, rather than focusing exclusively on the more traditional, unidirectional pathway (i.e., two-year to four-year). Second, these policies focus on credit accumulation and applicability towards a specific degree or program, rather than just the transferability of credit. The sections that follow address common course numbering, articulation agreements, transfer pathways, and reverse transfer, and their importance for expanding opportunities for historically underserved students.

Common Course Numbering

Common course numbering is a policy that can help to ease the administrative burden of articulating credit between institutions and thereby reduce credit loss. Participating institutions offer common course numbers, titles, and descriptions to ensure courses are the same across institutions and transfer easily. A common course numbering system helps students plan their course of study and can have the added benefit of increasing faculty engagement. Because faculty are the drivers of the content in a common course numbering system, faculty across campuses engage with each other and course materials and goals during the alignment process.[12]

As of 2018, 17 states have some version of common course numbering.[13] These systems typically exist within states’ public college systems, and public institutions are often required to participate, as in Florida.[14] Additionally, Florida has demonstrated the value of incorporating private colleges, including for-profit institutions.[15] The expansion of the system in this way can have the added benefit of acting as a quality assurance mechanism across sectors.

Texas’ common course numbering system is unique in that it is not a state-mandated policy, but rather a voluntary effort from higher education institutions within the state. One hundred thirty-seven institutions participate in the system, but are not required to use the common course numbering.[16] Instead, as a study commissioned by the Oregon Higher Education Commission to examine other state models shows, many institutions choose to align their course content with others through a web-based tool, in order to increase the ease of credit transfer.[17] This variation on the common course numbering approach gives institutions a bit more flexibility in avoiding renumbering all their courses. Some systems, such as in Arizona, focus more on course equivalency rather than course numbering itself. Arizona has a state-mandated shared unique numbering (SUN) system that is accessible by both students and parents, and guarantees course equivalency of lower-division courses at the three public universities and the state’s community colleges under the Arizona Board of Regents’ jurisdiction.[18]

Although common course numbering systems provide additional clarity and help student plan their course of study accordingly, the benefits rely on the system including a large group of institutions so students’ options are not limited. Moreover, common course numbering may identify course equivalencies across schools or campuses, but they do not guarantee that the courses fulfill the same requirements, for example, if the general education or specific major requirements may differ across campuses.

Articulation Agreements

Increasing transparency about how credits will transfer, especially for community college students, may have a large effect on students’ future degree attainment. Articulation agreements can serve as clear roadmaps to help facilitate transfer and should be used by counselors to help guide students throughout their education.

2+2 articulation agreements guarantee that associate’s degree graduates from state community colleges can transfer as juniors to state public four-year colleges and universities. In Florida, the 2+2 agreements, legislated by the state, allow students to transfer from a Florida college to any of 12 state universities, guaranteeing accurate distribution of credits and preventing students from re-taking courses that would require additional time, money, and effort.[19] According to the Florida Department of Education, nearly half of the juniors and seniors at state universities transferred from a Florida community college, and continued on to perform similarly to non-transfer students.[20] Although 2+2 programs may be helpful, many transfer students do not complete the associate’s degree and thus may not benefit from the articulation agree.

The specific enhancement programs used in the articulation process vary across campuses, with some universities using multiple programs across different majors or community colleges. There are many enhancement programs which are intended to facilitate the articulation of credits. The specific institutions participating in each enhancement program design it. Not all universities have enhancement programs with all community colleges, which may hamper some students’ ability to transfer to their desired institution.[21] University of Central Florida (UCF) has seen success with its DirectConnect program that guarantees community college students can transfer credits to UCF. As of 2014, roughly half of UCF bachelor’s degree completions came from associate’s degree transfers. Moreover, these transfer students are completing their bachelor’s at a higher rate than students who began as freshmen at UCF.[22] But across the Florida colleges, only half of associate’s degrees holders continue on to a public four-year university.[23] Of course, some of these students may have only been seeking an associate’s degree; however, given the growing labor market demand for bachelor’s degrees, the state would benefit from a higher uptake in the program.

The state of California has its own program called ASSIST (Articulation System Stimulating Interinstitutional Student Transfer), which contains all of the articulation agreements within the California system, which students can access to see how their credits from any California community college can transfer to any University of California or California State University campus. This system enables students to know ahead of time how their credits will transfer, and where their credits may have the most value when deciding on which campus to transfer to. Research suggests that ASSIST can be an effective tool for helping students plan their curriculum. However, without proper guidance, students may not be aware of the tool and the important information it contains.[24] Coupling systems like ASSIST with active counseling can help maximize the benefits of articulation agreements.

Usually, articulation agreements are for colleges within a single state, but there is at least one example of a two-state articulation agreement. Minnesota and North Dakota have a joint articulation agreement between their public university systems. Under the agreement, any general education credits or a completed associate’s degree can transfer to a four-year public college in either state.[25]

While many articulation agreements just ensure that credits transfer, the Illinois Articulation Initiative (IAI) helps students choose courses that will not only transfer, but fulfill requirements. The IAI includes a “package” of courses that participating two- and four-year institutions designate as fulfilling the general education requirements.[26] Students can complete a worksheet that maps which courses will apply to each general education requirement, and which courses still need to be completed. In this way, IAI helps ensure that credits not only transfer, but help students meeting bachelor’s degree requirements and thus avoid losing credits and wasting time.

Articulation agreements are an important step towards creating more opportunity for community college students, however, they only work if students understand them. In an analysis of 100 articulation agreements in Texas, community college students were unable to read and understand 93 of them.[27] States and institutions have a responsibility to ensure students are able to access and use articulation documents. Providing an ample number of counselors to work directly with students is one way to accomplish; developing streamlined agreements and straightforward websites (e.g., the IAI website) is another proactive step states can take. Additionally, decreasing the myriad number of articulation agreements can help by reducing the amount of information students need swift through to determine their various transfer options. Moreover, with fewer articulation agreements, counselors can more efficiently review and advise students as the individual context will matter less.

Transfer Pathways

Similar to articulation agreements in that they provide a guaranteed process to transfer credit, transfer pathways outline the set and sequence of courses needed if a student begins at a community college and aspires to complete a specific bachelor’s degree program at a particular four-year college. Like articulation agreements, transfer pathways guarantee that all community college credits will transfer to the four-year college or university if the pathway is followed. While articulation agreements ensure credits earned in community college will be accepted by the receiving four-year institution, they do not ensure these courses count towards the intended major requirements. A transfer pathway, however, provides a set of courses community colleges students can take to ensure their courses fulfill the requirements of their intended bachelor’s degree programs.[28] A well-designed transfer pathway can build upon an articulation agreement by ensuring the associate’s degree credits not only transfer to a four-year institution and guarantee junior-year status, but also the credits are fulfilling important major and general requirements to facilitate on-time completion for the bachelor’s degree.

Tennessee’s transfer pathways guarantee that any student who completes a prescribed list of coursework for a major can transfer these courses to any public two- or four-year college or university and they will count towards the completion of the major.[29] Transfer pathways can be a way to simplify the transfer process for community college students, and give them a clear roadmap of how they can pursue their degree in their major of choice. Moreover, students who may be mobile or who have to move for family or professional obligations can avoid the loss of credits thus simplifying the process of re-enrolling and continuing their course of study.

In 2012, California developed the Associate Degree for Transfer (ADT) to facilitate transfer between California Community College and California State University campuses. The ADT requires students to take a certain number of general education and major/discipline courses, from a specified list, in order to earn their associate’s degree. These requirements also allow the student to transfer the courses to a CSU campus where they will fulfill the relevant general education and major requirements.[30] The ADT program has been shown to lower the information barrier to successful transfer and improve associate’s degree graduation rates.[31] Although transfer pathways provide clear roadmaps for students, capacity restriction at some four-year institutions in California may limit the availability of certain majors, thus undercutting the value of the pathway.[32] It is important for states to build pathways that create opportunities rather than end in roadblocks. When majors at four-year colleges have limited capacity, community colleges could best serve students by developing more general pathways as well as educating students about other viable career choices.

Reverse Transfer Policies

Aside from improving the process to transfer from community colleges to four-year institutions, policies can also aid students who have already transferred. Reverse transfer policies allow students to earn an associate’s degree by combining credits earned at two-year institutions with credits earned at four-year institutions.[33] Reverse transfer is a particularly helpful strategy for ensuring more students earn a credential, considering that not all students who successfully transfer to a four-year institution will graduate with a bachelor’s degree. Without a credential of any kind, these students have lost not only time, money, and effort, but are missing out on future earnings. The Center on Education and the Workforce estimates that students who have some college credit but no associate’s degree make almost $200,000 less over their lifetimes than those who hold associate’s degrees.[34]

Evidence suggests that reverse transfer policies either improve or have a null effect on bachelor’s degree attainment, and have no negative effects.[35] There is additional evidence from student focus groups that degrees awarded via reverse transfer may act as a motivator for students, and are seen as something to have in case they do not finish their bachelor’s. In a study of transfer students’ perceptions of reverse transfer, researchers found that students valued associate’s degrees as a stepping stone to a bachelor’s degree, an increase in job marketability, and a recognition of their time and effort.[36] In addition, attaining an associate’s degree through reverse transfer also increased transfer students’ confidence in their abilities to excel at a four-year institution.[37] These policies can also be particularly helpful for veterans or other service members who may move and accumulate their credits in different locations.[38] In addition, military experience can sometimes count for college credit through reverse transfer policies. [39]

One particular initiative, called Credit When It’s Due (CWID), is being supported by a number of national philanthropic foundations to help states implement reverse transfer programs. Currently, 15 states have received CWID grants to support partnerships between community colleges and universities.[40] Through the CWID, an additional 15,860 associate’s degrees were awarded through reverse transfer as of 2016. [41] States such as Tennessee and Hawaii saw increases in associate’s degree attainment of 6.3 percent and 15.2 percent, respectively, after implementing CWID programs.[42] In another study of three states with these policies, Hawaii, Minnesota, and Ohio, transfer students who earned an associate’s degree via CWID had higher retention rates and completed their bachelor’s degree at a higher rate than students who were eligible for CWID but did not receive the associate’s degree.[43]

Summary

These four areas represent specific policy areas by which states can improve transfer opportunities for students. Streamlining of the credit transfer process is one way in which state governments can facilitate increased attainment. These explicit policies provide opportunities for students who may otherwise lose credits, fall short of a credential, or lack the guidance to successfully transition toward their desired credential. By simplifying the credit transfer process, state governments can better develop a credentialed workforce that is necessary for continued economic development.

In addition to awarding associate’s degrees post hoc, states should consider facilitating a range of other transfer directions. Students may transfer from two- to two-year, four- to four-year, or four- to two-year institutions. These variations are also more common than may be expected. For example, within 6 years of starting at a four-year institution, roughly 15 percent of students will transfer to a two-year college.[44] Articulation agreements and common course numbering can be helpful in these other transfer directions; however, specific pathways are not always designed to accommodate these students. Although earning a bachelor’s degree is the best ticket to increased earning potential, some evidence suggests that for students struggling in their bachelor’s program, transferring to a community college to earn an associate’s degree may be a good option that will allow, at the least, the student to benefit from the two-year credential in the labor market.[45] As such, policymakers should consider steps to facilitate this transfer process through explicit articulation mandates and capacity building for adequate advising through the transition.

Students also often transfer between public and private sectors. For example, of students who started at a community college in 2012 and then transferred to a four-year institution within six years, 19 percent moved to a private nonprofit and seven percent to a for-profit institution.[46] While some states have included private institutions in their policy approaches to transfer, this inclusion is not the usual course of action. Private colleges have much more autonomy than public institutions, and are not subject to the same state policies. However, policymakers should consider the ways in which they can incentivize private institutions to participate in common course numbering, articulation agreements, transfer pathways, data systems, and reverse transfer in order to maximize opportunities for students.

Reforming Remediation

Remediation, also known as developmental education, is preparatory coursework, tutoring, and/or advising and support for students who are deemed unprepared for college-level coursework. Remedial courses are taken by nearly 70 percent of students beginning at a community college and 40 percent of those at a public four-year college.[47] However, these courses, which are taken before college-level coursework, often cost students money but do not offer them any college credit. The extra time spent in remediation delays a student’s progress towards their degree, simultaneously increasing the chances that an event will disrupt them from their studies entirely.[48] Research suggests taking remedial courses generally slow students’ progress towards accumulating credits and graduation,[49] although the negative effects may dissipate for some students.[50] Nevertheless, financial aid may expire given the extra length of time, leading to possible loss of financial support before obtaining a degree.[51] Fewer than 50 percent of students who are recommended to take remedial courses complete the entire sequence, and only 10 percent of those placed in the lowest levels of math remediation complete the full sequence.[52] Moreover, some studies estimate that up to one-third of students assigned to a remedial course could have earned a B or better in college-level coursework.[53] Here we discuss three options for improving the remediation process: multiple measures for placement, co-requisite courses, and innovative pedagogy.

Multiple Measures for Remediation Placement

California, Texas, Florida, and Connecticut have passed legislation to reduce the number of students assigned to remedial courses.[54] Florida has also experimented with multiple remedial reforms at its state colleges. For example, in 2014, state colleges were banned from using placement exams for developmental courses, and were instead instructed to tailor their courses to students’ needs. This gave students the option of taking a developmental course if they wanted to, often offered in many ways, including co-requisite classes.[55] One study found that after the change, Florida’s remediation rates dropped by half, with the largest declines for Black students under 25.[56]

North Carolina’s Multiple Measures for Placement policy attempted to lower the number of remedial courses by providing different methods for placement aside from placement exams, such as through high school transcripts, standardized test scores, or prior coursework. One study found that students who were placed using high school transcript data were the most successful in their gateway courses in both English and math, compared to the other placement methods, and success rates persisted regardless of students’ race or ethnicity.[57] However, In Florida, recent evidence suggests that relying on high school grades alone may also lead to misplacement.[58] As such, a holistic approach to placement is likely the best option, although it may require additional resources.

In California, the governor signed AB 705 which mandated the use of high school coursework, grades, and/or grade point average in determining remediation placement. This move away from standardized tests as the sole placement mechanism was intended to improve completion rates and decrease the reliance on traditional remediation courses.[59] Although some community colleges may be voluntarily implementing multiple measures, state policymakers should consider implementing evidence-based mandates that can reduce the time students spend in remediation.

Co-requisite Remediation

One option for reforming remediation is to create co-requisite courses, where students can take college-level courses with additional supports. Co-requisite remediation can be effective by helping students adjust to more rigorous coursework, tailoring instruction to specific student needs, and helping build study skills. These benefits extend across groups of students and may provide opportunities for historically underserved populations to close education gaps. Some evidence suggests first generation students, Hispanic students, and students whose first language was not English, were found to benefit more from co-requisite remediation than other students,[60] however, these findings are not conclusive.[61]

A study of co-requisite remediation in Texas found five different models are being used throughout the state:[62]

- Paired-course models, where students enroll in the remedial and college-level course at the same time, as opposed to over two semesters.

- Extended instructional time models, where extra time is added to the college-level course, where oftentimes the same instructor provided additional support and instruction. However, all of the coursework is the same as the college-level course. This seamless model meant that many students were not aware that they were in a modified course, separated from college-ready students.

- Accelerated learning program models, which is one of the most common models. This model includes extra support in the classroom, often having lower student to teacher ratios, with a mixture of college-level and preparatory coursework. Oftentimes, college-ready students would also be in these classes.

- Academic support service models, which required mandatory regular participation in academic support services, such as the writing center or instructors’ office hours.

- Technology-mediated support models, which primarily relied on technology and computer-based modules, where students attended a different lab session, separate from college-ready students with a different instructor from the main course. A related study found that a blended approach to math remediation, where students complete work online, but in an on-campus lab with assistance from instructors, actually decreases students’ success in terms of pass rates, retention, and degree attainment.[63]

Preliminary results from the study of Texas community colleges have identified some challenges such as problems with scheduling separate courses, finding time for advising, obtaining stakeholder buy-in, and additional costs. Oftentimes, the most crucial aspects, such as finding a single instructor for multiple sections were more difficult to implement due to scheduling, cost, or buy-in. Understanding the potential challenges can help institution and state leaders design policies that preemptively address these issues. For example, in an effort to develop the highest quality co-requisite materials, the CSU Chancellor’s office worked closely with faculty, students, and campus administrators to build co-requisite courses that would meet students’ needs and ensure their success.[64] This helped ensure buy-in from stakeholders and gave administrators time to prepare schedules.

Although the methods of providing co-requisite remediation vary across states and may face implementation issues, research suggests these policies may be an effective way to improve student outcomes and close equity gaps. As such, policymakers should consider ways to promote and help colleges thoughtfully develop co-requisite courses.

Innovative Pedagogy

Given that many students who need remediation do not successfully complete the sequence, innovative new pedagogies have been designed to improve student learning and success. Math remediation pathways have historically been based around algebraic material. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching developed two new math curricula intended to expedite remediation and align the course content with the real world application of statistics and quantitative reasoning. These courses, called Statway and Quantway, have yielded improved remediation completion rates, with more students reaching college-level math.[65] The New Mathways Project aims to align mathematic pathways with students’ programs of study. Based on their majors, students can take algebra, statistics, or other quantitative reasoning courses. Students in these aligned mathematic sequences are up to four times as likely to pass their mathematical courses compared to students in traditional math remediation.[66]

Another pedagogical innovation is the CUNY Start program. Participants delay their matriculation at CUNY in order to spend one semester in intensive remediation courses that are coupled with tutoring and advising. Students do not use their financial aid for the program, and only pay a $75 fee. Early research shows that participants move through remediation materials more quickly than those enrolled in traditional courses and are more likely to persist to a second semester.[67]

Summary

These three sets of policies highlight various approaches taken to improve students’ likelihood of persisting and completing a degree. Given the persistent remediation problem that exists, it is unlikely that any of these policies are a silver bullet solution. Instead, we recommend a holistic approach to remediation. While there may be benefits for many students to skip remedial coursework all together, some may still need the additional classroom time. It is increasingly clear that single-test-based remediation placement policies are not the most effective way of increasing student success. Rather, multiple measures should be used, and students should be provided with a number of options based on their eventual goals.

Alternative Credentials and Pathways

Students who do not go through the standard four-year, residential college experience may often require different supports and take different paths to achieve a credential. For example, first-generation students may need more clarity and transparency through the college application process, adult learners may need more flexibility in the courses they take, and stop-out students may benefit from degree reclamation. Considering alternative methods of providing college-level education and credit is crucial to increasing the attainment rate. Outside of policies related to transfer and remediation, states can take an active role in facilitating the opportunities for the new majority of students. Here we discuss the role of state policy as it relates to six alternative pathways to obtaining a credential: centralized admissions, dual enrollment, decree reclamation, prior learning assessment, bachelor’s degrees at community colleges, and online education. Additionally, we discuss the role that alternative credentials may play in providing opportunities to historically underserved students.

Centralized Admissions

Centralized admissions policies for public college systems can decrease the complexity and increase the transparency in the college application process. These process improvements may encourage more students to apply, particularly students who are first generation or low income whose families may not have the resources or experience to fully understand the application process. States such as North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and New York (separate systems for SUNY and CUNY) offer centralized application processing, where students can submit the same application to multiple state institutions seamlessly.[68] These systems enable students to submit a single application and then select specific campuses.

In a related policy, California guarantees students a place at a California community college, state university, or University of California campus, based on eligibility requirements, which also helps to simplify the application process.[69] A key component of a streamlined application process is also providing information and outreach. Increasing students’ and others’ awareness of college application processes and how to apply for financial aid can be a low-cost way to increase enrollment from target populations.[70]

Idaho has recently implemented a Direct Admissions policy, which helps to streamline and centralize the admissions process.[71] Under this program, high school seniors in Idaho are automatically considered for admission at all Idaho public colleges based on their high school grades and SAT/ACT scores. The pre-acceptance holds a seat at the public institutions; however, students must then formally apply by June of their senior year to confirm their acceptance. This program is intended to simplify the application process and lower barriers to enrollment associated with submitting applications to many different institutions.

Dual Enrollment

High school students can also benefit from dual enrollment, in which they are permitted to take college-level courses while still in high school. These programs – which are often targeted toward low-income, first generation, or minority students – allow students to enroll in college-level courses at their high school, at a college campus, or even online.[72] These courses are meant to allow students to take college-level coursework and earn college credit at a low cost, boost students’ confidence in their ability to succeed in college, increase academic momentum heading into college, and decrease the time to degree. Dual enrollment has grown in popularity, with the number of students in dual-enrollment programs increasing by 80 percent from 2002 to 2010. Dual enrollment is a reliable path to attainment – only 12 percent of students who participated in dual enrollment during high school did not matriculate at a higher education institution by the time they were 20. Forty-one percent of dual enrollment students matriculate at a four-year college.[73]

Forty-nine states, all but New York, currently have state policies regarding dual enrollment programs. However, the policy details vary significantly. Some states mandate that all high schools provide opportunities, where others just develop a program into which high schools or districts can opt. The policies also vary on requirements to notify parents of the availability of dual enrollment and whether the credits are accepted at specific public colleges.[74] Although the policy designs vary significantly, the evidence supporting benefits of dual enrollment is consistent across states.

A study of dual enrollment programs in California found they increased high school graduation rates, increased the likelihood of attending a four-year college, decreased the likelihood of taking basic skills courses in college, and increased the accumulation of college credits for low-income students.[75] A randomized controlled trial in Tennessee on math dual enrollment courses found that students who dual enrolled in advanced algebra reduced enrollment in remedial math classes and increased enrollment in higher-level math courses, in addition to increasing the number of students who matriculate at a four-year university, as opposed to a two-year college.[76] Dual enrollment students also have similar or better grades in college than traditional students.[77]

In Texas, researchers found that dual enrollment students were up to 1.77 times more likely to earn a credential than students who did not take a dual enrollment class in high school.[78] In Florida, Minnesota, and Mississippi, more than 60 percent of dual enrollment students who first attended a community college earned a credential or degree five years after high school; this percentage was 30 or less for students in Louisiana, California, and West Virginia. Although these findings are from a descriptive analysis, they highlight the potential of dual enrollment policies. The range of credential completion rates suggests that variation in dual enrollment policies and the contexts in which these classes are offered may impact the effectiveness. As such, there is a need for additional research.[79]

Although dual enrollment benefits all students who participate, racial minorities and lower-income students are less likely to take dual enrollment than their wealthier, white peers.[80] This has led many to argue that the explicit expansion of dual enrollment to historically underserved communities can help close participation gaps among high school students as well as gaps in postsecondary access and attainment. States such as Minnesota have taken action to minimize the racial and economic disparity in dual enrollment students by subsidizing dual enrollment tuition.[81]

Degree Reclamation

In addition to focusing on younger learners and their pathways to attainment, many states are turning to adult learners to meet strategic degree attainment goals set by policymakers. More than 35 million Americans have some college experience but no credential.[82] Degree reclamation programs that focus on adult stop-outs, near completers, and veterans are being piloted in many states and at many institutions. These state-led programs focus on identifying and contacting adults who have college credit in order to inform them about how they might pursue their degree – including about the available resources that the state might have to assist these potential students with degree completion. By linking adult learners to financial aid opportunities and career coaching, states can improve access and attainment for these students. Within the broad category of adult learners, there are multiple sub-groups that can benefit from specific services tailored to the students’ circumstances.

One sub-group of adult learners is parents. Providing child care can assist parents who are returning to school to earn their degree. State policy can improve parents’ access to child care assistance while in school by making changes such as ensuring child care assistance for longer periods of time and adjusting requirements for qualifying for assistance.[83] Removing these barriers is an explicit way state governments can promote the return of adult learners to college.

Another important sub-group of adult learners is those who are currently incarcerated. Providing access to postsecondary education for incarcerated individuals not only decreases the likelihood of recidivism, but also improves reentry and workforce outcomes.[84] In addition, children of incarcerated parents are more likely to complete college if their parents have as well. [85] Currently, the Second Chance Pell Experiment, which is run through the U.S. Department of Education, provides education to incarcerated students in 28 states.[86] Degree reclamation targeted at those who are incarcerated has the potential to have extensive and important spillover effects for others in the prisoner’s life. These externalities underscore the importance of such programs to reducing social welfare benefits, generally, in addition to increasing state economic growth.

Project Win-Win was established to initiate degree reclamation through 60 institutions in nine states. These institutions identified students who were eligible for associate’s degrees but never received them, or were very close to completing their associate’s degrees. For students who were found eligible, Project Win-Win awarded 4,550 associate’s degrees, and brought 1,668 students back to school to complete their remaining credits to receive a degree.[87]

Individual states have also begun their own degree reclamation efforts. Texas’s Grad TX program is an online portal and comprehensive program offered by eight Texas universities that targets the 40,000+ adults in Texas who “stopped out” of college with 90 or more credit hours, but who have not finished the 120 credit-hour requirement to receive a bachelor’s degree.[88] The program provides students with a dedicated advisor, a financial aid specialist, and flexible degree programs that are targeted to adult learners. It also gives students a tool on the website that allows them to see how their earned credit would transfer to participating colleges in the program.

West Virginia has a multi-pronged effort to promote degree completion by adults, which is a specific goal in the state’s strategic plan and is tied to outcomes-based funding. The state’s effort includes its Higher Education Adult Part-Time Student Program, which gives need-based grants to eligible students for up to 10 years (covering tuition and fees). It also includes the DegreeNow initiative, which gives West Virginia colleges marketing grants to reach out to adult stop-outs and funds adult-focused orientation sessions for stop-outs who choose to enroll. As part of the statewide initiatives, the West Virginia State University has established an Office of Adult and Commuter Student Services.[89] Maryland’s State Plan for Postsecondary Education included the targeting of near-completers through the One Step Away grant program, which identifies, contacts, and supports students close to completing their degree, offering them information regarding available state initiatives to help them earn their degrees.[90]

Similarly, adult promise programs seek to provide resources to help adults return to college and earn a credential. For example, Tennessee Reconnect and Maine’s Adult Promise both provide financial assistance to adults seeking to return to college as well as pre-enrollment and career counseling to ensure adult learners are making the best choice for their goals. These programs are examples of ways that states can develop a strong pathway for adults to return to school and efficiently earn an economically relevant credential.

These examples suggest that many states are actively seeking to engage the 35 million adults with some credits but no degree. Given the range of experiences of these students, states must think critically about the specific supports sub-groups need in order to return to school and earn a credential.

Prior Learning Assessment

Adult learners can also benefit from alternative methods of earning credit, such as through prior military service or prior learning assessments. This method involves identifying students’ skills, such as through their work experience, that can lead to college-level credit. As of 2017, twenty-four states have some kind of prior learning assessment (PLA) policy.[91] Like many of the other methods mentioned, granting credit for prior learning experiences can help decrease the amount of required remediation or the time to graduation.[92] One study from the Council for Adult and Experiential Learning found that students who received prior learning credit reduced their time to degree from 2.5 to 10.1 months and had higher completion rates and lower debt totals than non-PLA students.[93] Pennsylvania has formed a coalition of community colleges called College Credit FastTrack, which is a task force with a mission to streamline access to prior learning assessment for adult learners. College Credit FastTrack utilizes a digital platform to inform adult students of their opportunities to earn credit, standardize the process, and to ensure transferability of credit amongst institutions.[94]

Credit can also be granted for military veterans specifically, which many states are trying to standardize at all institutions within the state. Twenty-nine states have a policy about awarding academic credit for military experience, with many of them also requiring that this information be available for veterans to access online, or that students must meet with an academic advisor.[95] For example, Colorado requires that higher education institutions implement a specific prior learning assessment policy for awarding academic credit for military experiences, and requires these institutions to provide guidance to military members on how to take advantage of this credit.[96] The policies vary by state, and sometimes by institution within a state. Policymakers have an opportunity to bring consistency to the process of awarding credit for military service, and making those credits transferable between colleges. For example, Alabama requires colleges to align credit for military experience to the American Council on Education’s CREDIT program, which would help facilitate the transfer of these courses.[97]

Bachelor’s Degrees at Community Colleges

In an effort to increase bachelor’s degree attainment, some states allow community colleges to offer bachelor’s degrees in certain programs in order to facilitate completion for students who may not be able or willing to travel to attend a four-year college or university. These programs can lower barriers associated with the complexity of transferring. Additionally, they may help close persistent equity gaps. Given that 40 percent of community college students transfer to four-year institutions and historically underserved students enroll in community colleges at disproportionate rates, allowing two-year colleges to offer a four-year degree may increase access to bachelor’s degree programs and close attainment gaps.[98] In Florida, 75 percent of students enrolled in community college bachelor’s programs were from underserved populations.[99]

Twenty-three states currently allow community colleges to offer bachelor’s degrees, but that does not necessarily mean many institutions in that state choose to do so.[100] Additionally, state policy usually limits the number and type of bachelor’s degrees community colleges can offer to prevent duplication with surrounding four year institutions.[101] California’s program, for example, is limited to 15 institutions, each of which may only offer one bachelor’s program and may not offer a degree offered by any public university.[102] California’s non-duplication policy is strongly linked to their Master Plan that sets clear boundaries between systems. Other states may not have such boundaries; they may also not have as many four-year campuses conveniently located to students. In these states, policy may be able to help the new majority increase bachelor’s attainment by allowing community colleges the freedom to offer these degree programs. This method is proving popular with students; within five years of Florida’s implementation of this pathway, the number of students enrolling at Florida community colleges to earn a bachelor’s degree almost quadrupled.[103] Students list the main reason as being cheaper and more convenient than a traditional four-year degree. Although this may be less expensive than a four-year institution, a recent study found that offering a bachelor’s degree resulted in higher tuition prices at community colleges.[104] These unintended consequences should be considered as they may negatively impact students pursuing shorter-term credentials.

Others have raised the concern that allowing community colleges to award bachelor’s degrees will result in mission drift that hinders opportunities for those whom community colleges are supposed to serve. Critics argue that this will lead to decreases in associate’s degree production. However, a study of community colleges in Florida showed that increasing community college bachelor’s degree programs actually increased overall associate’s degree production.[105] Another criticism is that community colleges offering bachelor’s degrees will decrease enrollment at surrounding four-year institutions, but evidence from Florida shows that four-year institutions actually saw an increase in graduation rates when two-year institutions in the area started offering bachelor’s degrees, awarding 25 percent more degrees per year. On the other hand, for-profit institutions saw a large decline, with degree completion dropping by 45 percent.[106]

There seems to be a large disparity in opinion about the issue between leaders at community colleges and four-year institutions. A survey by Inside Higher Ed showed that 70 percent of public university presidents think that community colleges offering bachelor’s degrees are expanding beyond their mission, and even more believe that community colleges are not “well positioned to help low-income and place-bound students complete a bachelor’s degree.” Fifty percent of these presidents do not think community colleges “can help address disparities in bachelor’s-degree attainment across different racial and ethnic groups.” In contrast, 80 percent of community college president feel that they are “in a strong position to offer bachelor’s degrees to students who would otherwise not have access to them due to cost or location.”[107]

Online Education

For students not enrolled full time and living on a residential campus, one of the largest barriers can be lack of convenient locations or times of courses. Online education, or distance learning, can be a good alternative for many students who require more flexibility. Online education is growing in popularity. Between 2012 to 2017, the number of undergraduates participating in online education grew by 11 percent. Overall, around 13 percent of undergraduates are earning their degree entirely online.[108] Online learning tends to increase access to higher education for adults and Black students – in part by lowering tuition[109] – however, there is also evidence that students who enroll in online programs are much less likely to complete their degree.[110] Online education appears to widen equity gaps, in part due to the quality of institutions relying heavily on online education (e.g., for-profit colleges with poor student outcomes that enroll disproportionate numbers of students of color and low-income students).[111] However, some specific online institutions report above-average results for their students. In addition, one study found that students who take some of their early courses online have a better chance of attaining their associate’s degree, compared to those that only attended in-person courses,[112] but others have pointed to flagging completion rates among online community college students.[113] Researchers have not fully identified the factors contributing to the success or failures. Many instead argue that blended learning may be the best option, where it is possible to increase access, but decrease cost and improve outcomes.[114]

Some states are using online learning specifically for adult completion colleges. For example, Connecticut’s Charter Oak State College is an online college designed with adult learners in mind. In 2018, the average age of a Charter Oak student was 38 and more than 80 percent of students were enrolled part-time.[115] Thomas Edison State University, in New Jersey, takes a similar approach to providing adult learners with online options in order to complete their degrees. Although a private institution, Western Governors University has been a pioneer in online and competency-based education. States seeking to use online education to improve opportunities for a more diverse set of students should consider the models of Charter Oak, Thomas Edison, and Western Governors.

While states can take an active role in creating online public institutions, they also play a role in regulating them. In order for an institution to operate within a state, it must first be authorized to do so by that state. The State Authorization Reciprocity Agreement (SARA) was developed to allow institutions authorized in a given state to offer distance education to students in other states that are also members of SARA. As of 2019, California is the only state not included in SARA and thus institutions must become authorized in California to offer online courses to students there. Opponents of SARA suggest that authorization is only as strong as the weakest state’s and strips participating states of their oversight ability.[116]

Policymakers also have influence over the cost of online education at public institutions. As the upfront costs associated with setting up an online program or college can be substantial, many colleges have resorted to charging additional online student fees. Some state governments, including Florida, have actively worked to limit these fees in order to avoid pricing students out of the market.[117] However, if these limits are not accompanied by sufficient investment from the state, online education may not be a financially viable option for institutions, which could limit access to adult learners.

Alternative Credentials

While alternative pathways to traditional credentials are one way to help the new majority access postsecondary education, we also consider the idea that new, alternative credentials can improve these students’ opportunities. The landscape of alternative credentials is varied and includes non-credit certificates, certifications, licenses, badges, and nanodegrees.[118] Although the labor market returns and utility of these alternative credentials is not fully understood, early evidence suggests there is significant variability in quality.[119]

While some of these credentials are offered at traditional colleges, the specific programs may not eligible for Title IV funding, thus students will have to pay out of pocket. These credentials are also offered by independent organizations that may receive limited government oversight. However, some states are taking proactive steps to ensure alternative credentials are valuable investments for students.

In Washington State, a state-level rule is being considered that would hold both degree-granting and private vocational schools responsible for students’ debt-to-earnings ratio. In Oregon, a law has been proposed that would prohibit non-degree schools from receiving more than 20 percent of their funding from state, federal, or self-guaranteed loans as well as require these institutions to spend more than 50 percent of tuition revenue on direct instruction.[120] Both of these seek to ensure the alternative credential market within their state is free from exploitative schools.

Nonprofit and community organizations have also sought to address the skills gap by providing free or low-cost training in technical areas. One example is Per Scholas, which offers participants free training to prepare them to take CompTIA certification exams (i.e., information technology certifications).[121] Participants have seen substantial growth in wages, although additional research should be conducted to understand the effects and scalability of such training programs.

Summary

This section identified a number of opportunities for states to improve access and attainment through alternative pathways to traditional degrees as well as supporting the development of high-quality alternative credentials. Of course, the specific set of policies that can improve opportunities for historically underserved students will depend on the state’s political, social, and economic contexts.[122] Policymakers must consider the new majority of higher education, and the best ways to serve them. Although context matters, we have identified a number of policies that appear to be effective at improving degree completion and states should leverage these successes in a targeted way.

Conclusion and Remaining Questions

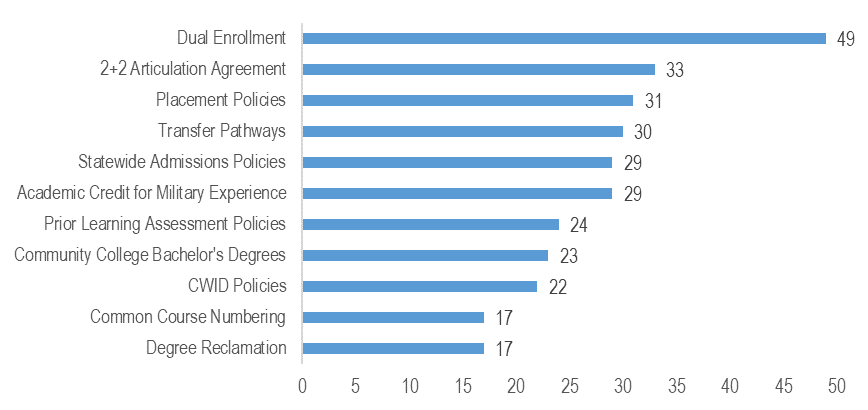

For states to meet their attainment goals, it is clear that they must focus on improving attainment for students outside of the traditional higher education framework. As seen in Figure 2, many states are already starting to implement policies that could address the issues discussed above. However, with the variability in state implementation, and the relative novelty of many of these policies, there are still many questions that existing research has not yet answered.

Figure 2 – States with Various Alternative Pathways Policies

Source: Education Commission of the States, Institute for Higher Education Policy

The prevalence of dual enrollment programs likely reflects the success of such programs. However, as noted above, additional research must be done to identify the most effective ways of administering these programs. States must also engage adult learners in order to achieve their attainment goals. Degree reclamation, despite not being widespread, is one way states can achieve this. Similarly, transfer-related policies are ways states can ensure those enrolled in public colleges receive the necessary credentials to be successful in the labor market. The research shows that policies related to simplifying transfer, reforming remediation, and developing alternative credential pathways can help lower barriers to access to higher education and completion of credentials for the new majority of students. We recommend that state policymakers rely on currently available evidence to develop a comprehensive plan to address the needs of all students. Through state policy, the structures around accessing and the tools for succeeding in higher education can be transformed from a system rooted in ideas that the traditional college student is still the typical student.

While this brief summarizes the potential benefits of a range of policies it also points to important questions that still need to be answered. The following questions could guide future research to provide deeper insights to the best policies states can pursue to increase attainment among the new majority of students.

- State contexts matter. As such, in what environments are these policies most effective?

- What combinations of these policies lead to the highest postsecondary attainment?

- Are some policies more cost effective than others? How does this cost effectiveness vary across states?

- Closing income-based and racial/ethnic gaps are necessary for states to meet their attainment goals. Which policies will be most effective at achieving these goals?

- What are the long-term effects of these policies? Would they have the same effects in all states?

- There is an issue of quality control for many of these policies, such as remediation reform, dual enrollment, prior learning assessment, community college bachelor’s programs, and online programs. How can policymakers address these issues?

Endnotes

- The authors thank Alexandra W. Logue, Research Professor in CASE (the Center for Advanced Study in Education) of the Graduate Center of The City University of New York (CUNY), and Shanna Smith Jaggars, Assistant Vice-Provost, Research & Program Assessment, The Ohio State University, for their review of this issue brief and their helpful suggestions. ↑

- Joseph C. Chen, “Nontraditional Adult Learners: The Neglected Diversity in Postsecondary Education,” SAGE Open 7, no. 1 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2158244017697161; and Louis Soares, Jonathan S. Gagliardi, and Christopher J. Nellum, “The Post-Traditional Learners Manifesto Revisited,” American Council on Education (2017), https://www.acenet.edu/Documents/The-Post-Traditional-Learners-Manifesto-Revisited.pdf. ↑

- Thomas D. Snyder, Cristobal de Brey, and Sally A. Dillow, “Digest of Education Statistics 2017, NCES 2018-070,” National Center for Education Statistics (2019), https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018070.pdf. ↑

- Robert Kelchen, “A Look at College Students’ Living Arrangements,” Kelchen on Education (blog), May 28, 2018, https://robertkelchen.com/2018/05/28/a-look-at-college-students-living-arrangements/. ↑

- National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, “Completing College: A National View of Student Completion Rates—Fall 2012 Cohort,” December 2018, https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/SignatureReport16.pdf. ↑

- National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, “Completing College: A National View of Student Completion Rates—Fall 2012 Cohort,” December 2018, https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/SignatureReport16.pdf. ↑

- Doug Shapiro, Afet Dundar, Phoebe Khasiala Wakhungu, Xin Yuan, Angel Nathan, and Youngsik Hwang, “Time to Degree: A National View of the Time Enrolled and Elapsed for Associate and Bachelor’s Degree Earners,” National Student Clearinghouse (2016), https://nscresearchcenter.org/signaturereport11/. ↑

- Davis Jenkins and John Fink, “Tracking Transfer: New Measures of Institutional and State Effectiveness in Helping Community College Students Attain Bachelor’s Degrees,” Community College Research Center, January 2016, https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/tracking-transfer-institutional-state-effectiveness.html. ↑

- David B. Monaghan and Paul Attewell, “The Community College Route to the Bachelor’s Degree,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 37, no. 1 (2015): 70-91, https://doi.org/10.3102%2F0162373714521865. ↑

- United States Government Accountability Office, “Students Need more Information to Help Reduce Challenges in Transferring College Credits,” August 2017, https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/686530.pdf. ↑

- Brenda Bautsch, “State Policies to Improve Student Transfer,” National Conference of State Legislatures, January 2013, http://www.ncsl.org/documents/educ/student-transfer.pdf. ↑

- Oregon Higher Education Coordinating Commission, “Common Course Numbering House Bill 2979 Report: A report to the Oregon Legislature,” December 1, 2013, https://www.oregonlegislature.gov/citizen_engagement/Reports/CCN_Report2013.pdf. ↑

- Education Commission of the States, “Transfer and Articulation Statewide Common Course Numbering,” June 2018, http://ecs.force.com/mbdata/MBquest3RTA?Rep=TR1802. ↑

- Florida Department of Education, “Statewide Course Numbering System,” revised 2019, https://flscns.fldoe.org/LinkUploads/SCNS%202019%20Handbook.pdf. ↑

- American Association of State Colleges and Universities, “Developing Transfer and Articulation Policies That Make a Difference,” July 2005, http://www.aascu.org/uploadedFiles/AASCU/Content/Root/PolicyAndAdvocacy/PolicyPublications/Transfer%20and%20Articulation.pdf. ↑

- Texas Common Course Numbering System, accessed July 31, 2019, https://www.tccns.org/. ↑

- Oregon Higher Education Coordinating Commission, “Common Course Numbering House Bill 2979 Report: A report to the Oregon Legislature,” December 1, 2013, https://www.oregonlegislature.gov/citizen_engagement/Reports/CCN_Report2013.pdf. ↑

- S.B. 1186, Sess. Of 2010 (Arizona 2010), https://www.azleg.gov/legtext/49leg/2r/bills/sb1186h.pdf ↑

- Florida Department of Education, “Statewide 2+2 Articulation Agreement: A Guide to Florida’s Policies,” October 2018, https://www.floridacollegesystem.com/sites/www/Uploads/Articulation%20Agreement/Articulation%20Guide%20Final.pdf. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Sophie Quinton and National Journal, “Why Central Florida Kids Choose Community College,” The Atlantic, February 10, 2014, https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2014/02/why-central-florida-kids-choose-community-college/430605/. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- The Campaign for College Opportunity, “The Transfer Maze: The High Cost to Students and the State of California,” (2017), https://collegecampaign.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/CCO-2017-TransferMazeReport-27.pdf. ↑

- Brenda Bautsch, “State Policies to Improve Student Transfer,” National Conference of State Legislatures, January 2013, http://www.ncsl.org/documents/educ/student-transfer.pdf. ↑

- Illinois Transfer Portal, “What is IAI?” (2019), https://itransfer.org/aboutiai/. ↑

- Zachary Wayne Taylor, “Inarticulate Transfer: Do Community College Students Understand Articulation Agreements?” Community College Journal of Research and Practice 43, no. 1 (2019): 65-69, https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2017.1382400. ↑

- Brenda Bautsch, “State Policies to Improve Student Transfer,” National Conference of State Legislatures (2013), https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/bitstream/handle/10919/83161/StatePoliciesStudentTransfer.pdf?sequence=1. ↑

- Tennessee Transfer Pathway, accessed July 30, 2019, https://www.tntransferpathway.org/. ↑

- California Community Colleges, “CCC – Associate Degree for Transfer,” (2019), https://www2.calstate.edu/apply/transfer/Pages/ccc-associate-degree-for-transfer.aspx. ↑

- Rachel Baker, “The Effects of Structured Transfer Pathways in Community Colleges,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 38, no. 4 (2016): 626-646, https://doi.org/10.3102%2F0162373716651491. ↑

- California State University, “Impacted Undergraduate Majors and Campuses, 2020-21,” (2019), https://www2.calstate.edu/attend/degrees-certificates-credentials/Pages/impacted-degrees.aspx. ↑

- We define reverse transfer policies as those that allow students to retroactively earn an associate’s degree after transferring to a four-year institution. This differs from other uses of the term to mean students transferring from four- to two-year institutions. ↑

- Indiana Commission for Higher Education, “Reverse Transfer: Context and Policy Guidance,” November 1, 2017, https://www.in.gov/che/files/23.pdf. ↑

- Jason L. Taylor and Matt Giani, “Modeling the Effect of the Reverse Credit Transfer Associate’s Degree: Evidence from Two States,” The Review of Higher Education 42, no. 2 (2019): 427-455, https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2019.0002. ↑

- Edén Cortes-Lopez and Jason L. Taylor, “Reverse Credit Transfer and the Value of the Associate’s Degree: Multiple and Contradictory Meanings,” Community College Journal of Research and Practice (2018): 1-17, https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2018.1556358. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Indiana Commission for Higher Education, “Reverse Transfer: Context and Policy Guidance,” November 1, 2017, https://www.in.gov/che/files/23.pdf. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Office of Community College Research and Leadership, “Credit When It’s Due,” University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2019, https://occrl.illinois.edu/cwid. ↑

- Jason L. Taylor and Edén Cortes-Lopez, “CWID Data Note: Reverse Credit Transfer: Increasing State Associate’s Degree Attainment,” April 2017, http://degreeswhendue.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Taylor-Cortes-Lopez-2017.pdf. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Jason L.Taylor and Sheena A. Kauppila, “CWID Data Note: Reverse Credit Transfer and the Associate’s Degree Advantage,” November 2017, http://degreeswhendue.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Taylor-Kauppila-2017-2.pdf. ↑

- Don Hossler, Doug Shapiro, Afet Dundar, Jin Chen, Desiree Zerquera, Mary Ziskin, and Vasti Torres, “Reverse Transfer: A National View of Student Mobility from Four-Year to Two-Year Institutions,” National Student Clearinghouse (2012), ↑

- Vivian Yuen Ting Liu, “Do Students Benefit From Going Backward? The Academic and Labor Market Consequences of Four-to Two-Year College Transfer,” Community College Research Center (2016), https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/media/k2/attachments/capsee-do-students-benefit-from-going-backward.pdf. ↑

- Doug Shapiro, Afet Dundar, Faye Huie, Phoebe Khasiala Wakhungu, Xin Yuan, Angel Nathan, and Youngsik Hwang, “Tracking Transfer: Measures of Effectiveness in Helping Community College Students to Complete Bachelor’s Degrees,” National Student Clearinghouse (2019), https://nscresearchcenter.org/signaturereport13/. ↑

- Xianglei Chen and Sean Simone, “Remedial Coursetaking at U.S. Public 2- and 4-Year Institutions: Scope, Experiences, and Outcomes,” National Center for Educational Statistics (2016), https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2016/2016405.pdf. ↑

- Bridget Terry Long, “Proposal 6: Addressing the Academic Barriers to Higher Education,” The Hamilton Project, https://www.luminafoundation.org/files/resources/higher-education-remediation-long.pdf. ↑

- Jeffrey C. Valentine, Spyros Konstantopoulos, and Sara Goldrick-Rab, “What Happens to Students Placed Into Developmental Education? A Meta-Analysis of Regression Discontinuity Studies,” Review of Educational Research 87, no. 4 (2017): 806-833, https://doi.org/10.3102%2F0034654317709237. ↑

- Angela Boatman and Bridget Terry Long, “Does Remediation Work for All Students? How the Effects of Postsecondary Remedial and Developmental Courses Vary by Level of Academic Preparation,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 40, no. 1 (2018): 29-58, https://doi.org/10.3102%2F0162373717715708. ↑

- Bridget Terry Long, “Proposal 6: Addressing the Academic Barriers to Higher Education,” The Hamilton Project, https://www.luminafoundation.org/files/resources/higher-education-remediation-long.pdf. ↑

- Thomas Bailey, Dong Wook Jeong, and Sung-Woo Cho, “Referral, Enrollment, and Completion in Developmental Education Sequences in Community Colleges,” Economics of Education Review 29, no. 2 (2010): 255-270, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2009.09.002. ↑

- Judith Scott-Clayton,”Do High-Stakes Placement Exams Predict College Success? CCRC Working Paper No. 41,” Community College Research Center, Columbia University (2019), https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED529866.pdf. ↑

- Ashley A. Smith, “Legislative Fixes for Remediation,” Inside Higher Ed, May 8, 2015, accessed June 21, 2019, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/05/08/states-and-colleges-increasingly-seek-alter-remedial-classes. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Shouping Hu, Toby J. Park, Chenoa S. Woods, David A. Tandberg, Keith Richard, and Dava Hankerson, “Investigating Developmental and College-Level Course Enrollment and Passing before and after Florida’s Developmental Education Reform. REL 2017-203,” Regional Educational Laboratory Southeast (2016), https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED569942. ↑

- Center for Community College Student Engagement, “The Unprepared Student and Community Colleges: 2016 National Report,” (2016), https://www.ccsse.org/docs/Underprepared_Student.pdf. ↑

- Daniel M. Leeds and Christine G. Mokher. “Improving Indicators of College Readiness: Methods for Optimally Placing Students into Multiple Levels of Postsecondary Coursework,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis (2019), https://doi.org/10.3102%2F0162373719885648. ↑

- AB 705, Sess. of 2017 (California 2017), https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180AB705. ↑

- Trey Miller, “Panel Paper: Experimental Evidence on the Short Term Impacts of Corequisite Remediation,” Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management, accessed June 21, 2019, https://appam.confex.com/appam/2018/webprogram/Paper26670.html. ↑

- Alexandra W. Logue, Mari Watanabe-Rose, and Daniel Douglas, “Should Students Assessed as Needing Remedial Mathematics Take College-Level Quantitative Courses Instead? A Randomized Controlled Trial,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 38, no. 3 (2016): 578-598, https://doi.org/10.3102%2F0162373716649056. ↑

- Lindsay Daughtery, Celia J. Gomez, Diana Gehlhaus Carew, Alexandra Mendoza-Graf, and Trey Miller, “Designing and Implementing Corequisite Models of Developmental Education,” Rand Corporation (2018), https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR2300/RR2337/RAND_RR2337.pdf. ↑

- Whitney Kozakowski, “Moving the Classroom to the Computer Lab: Can Online Learning with In-Person Support Improve Outcomes in Community Colleges?” Economics of Education Review 70 (2019): 159-172, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2019.03.004. ↑

- Christianne Salvador, “New CSU Students to Benefit from Changes to Developmental Education,” California State University, 2018, https://www2.calstate.edu/csu-system/news/Pages/New-CSU-Students-to-Benefit-from-Changes-to-Developmental-Education.aspx. ↑

- James Van Campen, Nicole Sowers, and Scott Strother, “Community College Pathways: 2012-2013 Descriptive Report,” Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching (December 2013), https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED560119.pdf. ↑

- Center for Community College Student Engagement, “The Unprepared Student and Community Colleges: 2016 National Report,” (2016), https://www.ccsse.org/docs/Underprepared_Student.pdf. ↑

- Susan Scrivener, Himani Gupta, Michael J. Weiss, Benjamin Cohen, Maria Scott Cormier, and Jessica Brathwaite, “Becoming College-Ready: Early Findings from a CUNY Start Evaluation,” MDRC (2018), https://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/CUNY_START_InterimExecSum-Final_0.pdf. ↑

- The College Board, “The College Completion Agenda State Policy Guide,” http://www.ncsl.org/documents/educ/policyguide_062810sm.pdf. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Next Steps Idaho, “Direct Admissions,” Idaho State Board of Education (2019), https://nextsteps.idaho.gov/resources/direct-admissions-guide-for-families/. ↑

- In Texas, researchers found that dual enrollment students, as compared to AP exam students, are more likely to be rural, have lower incomes, have lower SAT scores, have lower GPAs, and more likely to be African American or Hispanic. Philip M. Sadler, Gerhard Sonnert, Robert H. Tai, and Kristin Klopfenstein, AP: A Critical Examination of the Advanced Placement Program, Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press (2010), http://www.hepg.org/hep/book/120/AP. ↑

- Shalina Chatlani, “Dual Enrollment Is Increasing College-Going Behavior, But Only for Some Students,” August 27, 2019, Education Dive, https://www.educationdive.com/news/dual-enrollment-is-increasing-college-going-behavior-but-only-for-some-stu/530590/. ↑

- Education Commission of the States, “Dual Enrollment – All State Profiles,” accessed October 2, 2019, http://ecs.force.com/mbdata/mbprofall2?Rep=DE19A. ↑

- Katherine L Hughes, Olga Rodriguez, Linsey Edwards, and Clive Belfield, “Broadening the Benefits of Dual Enrollment,” San Francisco, CA: James Irvine Foundation, (2012), http://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/media/k2/attachments/broadening-benefits-dual-enrollment-rp.pdf. ↑

- Steven W. Hemelt, Nathaniel Schwartz, and Susan M. Dynarski. “Dual-Credit Courses and the Road to College: Experimental Evidence from Tennessee.” (2019), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3427620. ↑

- Jill D. Crouse and Jeff Allen. “College Course Grades for Dual Enrollment Students,” Community College Journal of Research and Practice 38, no. 6 (2014): 494-511, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2011.567168. ↑

- Ben Struhl, and Joel Vargas, “Taking College Courses in High School: A Strategy Guide for College Readiness–The College Outcomes of Dual Enrollment in Texas,” Boston, MA: Jobs for the Future (2012), https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED537253.pdf. ↑

- John Fink, Davis Jenkins, and Takeshi Yanagiura, “What Happens to Students Who Take Community College “Dual Enrollment” Courses in High School?” Community College Research Center (September 2017), https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/media/k2/attachments/what-happens-community-college-dual-enrollment-students.pdf. ↑

- Di Xu, John Fink, and Sabrina Solanki, “College Acceleration for All? Mapping Racial/Ethnic Gaps in Advanced Placement and Dual Enrollment Participation,” Community College Research Center (2019), https://tacc.org/sites/default/files/documents/2019-11/crdc-advanced-placement-dual-enrollment-access.pdf. ↑

- Joshua Ddamulira, “Who’s Participating in Dual Enrollment?” New America (2017), https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/edcentral/whos-participating-dual-enrollment/. ↑

- Doug Shapiro, Mikyung Ryu, Faye Huie, and Qing Liu, “Some College, No Degree,” Herndon, VA: National Student Clearinghouse (2019), https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/SCND_Report_2019.pdf. ↑