Library Acquisition Patterns: Preliminary Findings

Several years ago, we set out to better understand how both library acquisition practices and the distribution patterns of publishers and vendors were evolving over time.[1] Within the academic publishing community, there is a sense that academic libraries are acquiring fewer and fewer books and that university presses are struggling amid declining sales. The latter may certainly be true—a recent UK study found that between 2005 and 2014, retail sales of academic books dropped by 13 percent[2]—but what if the academic libraries that constitute part of that market were in reality not making fewer purchases? As new vendors and acquisition methods disrupt customary means of acquiring books, Joseph Esposito, Ithaka S+R’s frequent collaborator and consultant, was inspired to ask whether book sales were actually depressed, or if they only appeared to be because academic libraries were bypassing the traditional wholesale vendors whose metrics are used by university presses to assess sales to libraries for companies like Amazon.[3]

To address this question, Ithaka S+R’s Roger Schonfeld and Liam Sweeney developed a data collection method that involved obtaining acquisitions data through an integrated library system (ILS).[4] With the help of Betsy Friesen and Michael Johnson at the University of Minnesota, we created a canned report and query that academic institutions using Ex Libris’s Alma could easily implement to extract their data and supply us with a complete list of acquisitions by fiscal year. A pilot conducted with four academic libraries in 2016 proved that this method not only yielded viable data but was also scalable.[5] Last year we received funding from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and the Library Acquisition Patterns (LAP) project was able to expand into a large-scale, national study that also incorporated data from OCLC’s WorldShare Management Services (WMS).[6]

This preliminary analysis examines book acquisitions from 54 libraries—ranging from small private liberal arts colleges to public research universities—that use WMS.[7] We asked participants for data on their acquisitions between fiscal years 2013 to 2017. Because start and end dates for fiscal years vary by institution, we coded fiscal years as the year when the fiscal period ends for the purpose of this analysis. While some institutions were able to provide data for all five years, most were not, and we were therefore unable to perform a meaningful longitudinal analysis of acquisition patterns in the aggregate and within sectors using WMS data alone. As a result we are focusing our findings on fiscal year 2017, the most recent year for which all participants were able to provide data on their acquisitions.

Preliminary Findings

Material Format

In the 2017 fiscal year, participating institutions acquired a total of 178,120 books. Of these, approximately 96 percent were acquired as tangible print books and the remaining four percent as electronic books (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Percentage of Print vs. Electronic Books

Acquisition Method

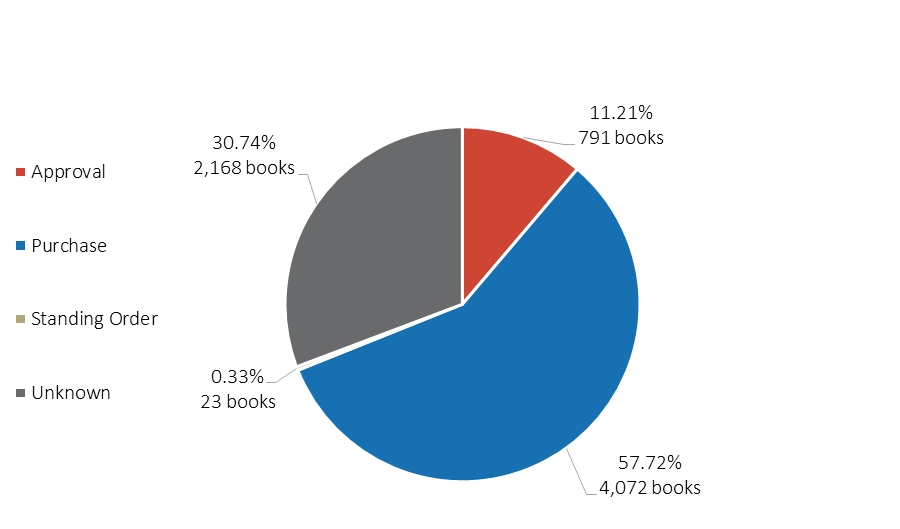

Print books were overwhelmingly acquired through a firm, one-time purchase, with 95 percent obtained in this manner. Only a little more than three percent of books were acquired through an approval plan, and half of that number were through a standing order. Electronic books, however, were acquired in drastically different ways. Firm purchases of ebooks fell to a little less than 60 percent, while approvals rose to 11 percent. Ebooks acquired through “unknown” means shot up to 31 percent (see Figure 2 and Figure 3). Although we do not know what these unknown acquisition methods are, one thing to note is that integrated library systems often have no systematic way of capturing items obtained as demand-driven acquisitions (DDA). It is therefore possible that these unknown acquisition methods include DDA. These preliminary findings are unexpected and represent an area that we would like to delve into with greater detail in the next stages of the analysis. Are these findings consistent with other library’s buying practices?

Figure 2. Percentage of Print Books by Acquisition Method

Figure 3. Percentage of Electronic Books by Acquisition Method

Price

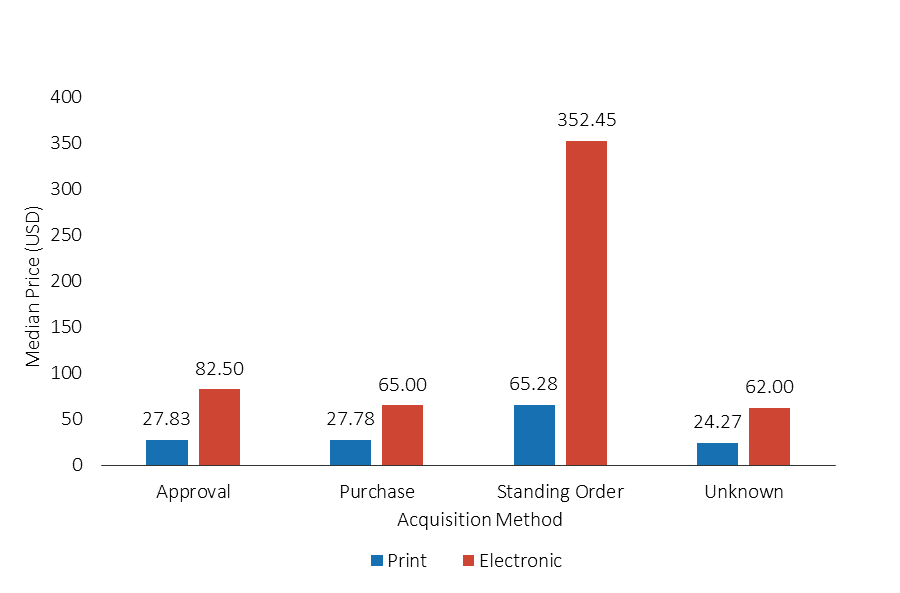

The median price of electronic and print books by their acquisition method also varies to a wide extent (see Figure 4). Print books were acquired for a substantially lower median cost than electronic books, especially for print books and ebooks obtained through standing orders. While these figures suggest that electronic books generally tend to have their prices set at substantially higher rates, this could also mean that the specific books that institutions choose to acquire in electronic format simply cost more to obtain.

Figure 4. Median Price of Print and Electronic Books by Acquisition Method

Institutional Type Differences

We also examined the number of book acquisitions by institutional characteristics. When examined in relation to their sector, we found that public institutions at the masters and doctoral level acquire a substantially higher number of books on average (see Figure 5). However, because we only have data for private baccalaureate schools, we were unable to assess whether this trend applies to public baccalaureate schools as well. Furthermore, because each category contains a relatively small number of schools, these findings should not be considered representative of acquisition patterns at institutions on the whole. We hope that further data gathering, especially from Alma participants, will bring greater balance to our participants in terms of institutional types.

Figure 5. Average Number of Acquired Books by Carnegie Classification and Sector

Book Vendors

Among vendors, GOBI Library Solutions (formerly YBP) encompasses nearly half the market share of book acquisitions made in FY2017 by libraries in our sample, while Amazon has become the second largest book distributor with a quarter of the market (see Figure 6). Other top vendors have no more than six percent of the overall market. Participating institutions spent $9,407,190 on books during the 2017 fiscal year, with median prices among the top ten vendors ranging from close to $18 to just under $35 (see Figure 7).

Figure 6. Market Share of Top 10 Book Vendors

Figure 7. Median Book Price of Top 10 Vendors

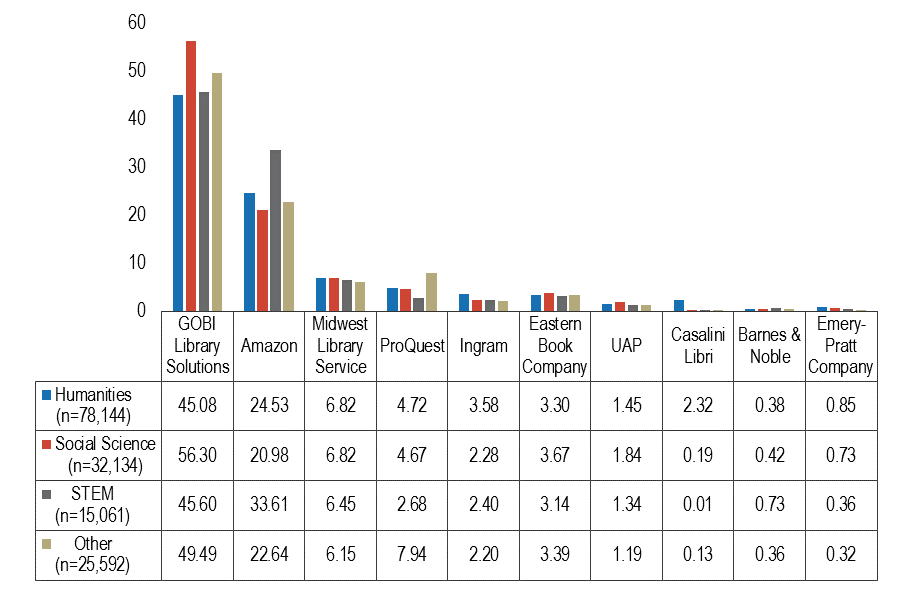

By discipline, GOBI and Amazon remain the top vendors across books in the humanities, social sciences, STEM, and other disciplines, although GOBI’s market share increases to 56 percent within the social sciences, while Amazon holds nearly 34 percent of the STEM market (see Figure 8). However, we question how much of these vendors’ market share is driven by the libraries themselves and their decisions to obtain books in different disciplines from particular vendors. As our research continues, and as we incorporate acquisitions data from significantly more schools, we will be interested to see whether these vendors remain the largest distributors. Amazon’s substantial presence is extremely notable among the libraries in our sample as well, and we look forward to seeing whether it has an equally substantial presence among Alma participants in the next phase of work on this project.

Figure 8. Market Share of Top 10 Book Vendors by Discipline (%)

Conclusion and Next Steps

Our findings indicate that print books dominated book acquisitions in 2017 at the 54 participating institutions in our data set. Most of these were acquired through a firm purchase in contrast to ebooks, of which nearly half were acquired through other methods and at significantly higher prices. The average number of book acquisitions was substantially higher among public universities as well. Amazon has come to capture 25 percent of the market, making it the second largest book vendor for these institutions. By discipline, titles focused on the humanities made up roughly half of all book acquisitions in the last fiscal year.

These findings provide a snapshot of library acquisition patterns among universities that utilize OCLC’s WorldShare Management Services. While the findings in this preliminary report should not be viewed as representative of the acquisition patterns present in all academic libraries, they nevertheless yield important insights into current practices employed in acquiring books and illuminate which areas may be of most interest to dive into for a deeper analysis. The next step will be to incorporate acquisitions data from as many Ex Libris Alma participants as possible. Because we expect to add many larger research universities to our sample, it should give us the opportunity to examine patterns more broadly and at institutions with larger and potentially more diverse acquisitions. This amount of data and the greater number of schools will also allow us to take a closer look at the different patterns that may exist within different sectors of the academy and over time.

Throughout the summer we will continue to gather data to ensure a large number of acquisition records from a diverse group of institutions. The next stage of this analysis will see us answering questions that include but are not limited to:

- How many books are academic libraries acquiring on average per year, and is there any notable trend in the number of acquisitions?

- In which formats and through which methods are academic libraries acquiring books? Have these patterns seen any change from 2013 to 2017?

- How do acquisition patterns vary by institution type and sector and how are these patterns changing over time?

- From which publishers are libraries acquiring books and through which vendors?

We will present our findings in a final report in fall 2018.

Endnotes

[1] Katherine Daniel, “Understanding Library Acquisition Patterns: Large-Scale National Study Launches,” Ithaka S+R (blog), September 6, 2017, http://www.sr.ithaka.org/blog/understanding-library-acquisition-patterns/.

[2] Michael Jubb, “Academic Books and Their Futures: A Report to the AHRC and the British Library” (London: 2017), https://academicbookfuture.files.wordpress.com/2017/06/academic-books-and-their-futures_jubb1.pdf.

[3] Joseph Esposito, “Researching Amazon and Libraries,” The Scholarly Kitchen (blog), November 12, 2014, https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2014/11/12/researching-amazon-and-libraries/.

[4] Roger C. Schonfeld and Liam Sweeney, “Analyzing Library Acquisitions: Vendors, Publishers and Integrated Library Systems,” Ithaka S+R (blog), March 3, 2016, http://www.sr.ithaka.org/blog/analyzing-library-acquisitions/.

[5] Liam Sweeney, “Library Acquisitions Pilot: Looking at the Data,” Ithaka S+R (blog), March 23, 2016, http://www.sr.ithaka.org/blog/library-acquisitions-pilot-looking-at-the-data/.

[6] We would like to express our gratitude to the participants for agreeing to supply us with their acquisitions data, and especially OCLC’s Jonathan Blackburn for extracting it.

[7] The study included 46 private institutions (27 at the baccalaureate level, 17 at the masters level, two at the doctoral level) and eight public institutions (five masters level, three doctoral level).

Attribution/NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of the license, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.