Living Wages

Art Museum Leaders Confront Persistent Staff Compensation Challenges

Introduction

Movements for pay equity, including raising minimum wages and increasing pay transparency, have been building momentum in grassroots and policy arenas across the United States.[1] As a result, museums, like many employers, face mounting pressure to better align their compensation practices with their diversity, equity, and inclusion commitments.[2] Ithaka S+R’s research has found that the majority of art museum directors view pay equity as a high priority at their organization and are finding attracting and retaining diverse and talented staff to be more challenging. At the same time, these museums face tight budgetary restrictions and changing revenue levels from admissions as they reopen following pandemic closures.[3]

Pay equity is an issue of growing importance in museums. Historically, the American Association of Museum Directors’ (AAMD) Salary Survey has been a publicly available tool for data-driven decision making in the field, often used in museums’ salary benchmarking. More recently, worker-led efforts have brought new attention to salary transparency. In 2019, US museum workers created a spreadsheet to collect salary data with the goals of empowering employees with information and decreasing salary inequality.[4] The National Emerging Museum Professionals Network continues to advocate for pay equity and transparency, maintaining a database of museum job postings that do not offer salary ranges as well as unpaid internships.[5] Museums have also become sites of labor organizing in recent years; an analysis of news reports found that employees at around two dozen museums have formed unions since 2019.[6] In the wake of these worker-led initiatives, norms and policies have been put in place to standardize pay practices. In 2022, the American Alliance for Museums stipulated that any job posted on its job board had to include salary information. Around the same time, New York City began requiring that employers list salary ranges for open positions as part of the New York City Human Rights Law.[7] This legislation is just one example of state and municipal pay transparency laws but could shape the field significantly due to the high concentration of museum jobs in the metropolitan area.[8]

Museums are, however, limited in how they can respond to workers’ needs for higher and more equitable wages due to financial and organizational constraints. Both cycles of the Art Museum Director Survey revealed that on average, personnel costs already make up half of museum budgets.[9] Raising salaries is often not as simple as reallocating budgetary priorities, as the largest sources of revenue for non-academic museums—private philanthropy and endowments—require long-term planning and network building with wealthy donors, and in the case of endowments, have stipulations around their use.[10] This means that museum leaders have to find ways to increase their recurring earned revenue from admissions, stores, cafes, and events, or decrease their recurring expenses in order to sustainably offer wage increases to staff. The global decline in museum visits coupled with rising energy costs makes increasing revenue and decreasing expenses particularly challenging.

What organizational, economic, and social factors characterize the salary landscape for art museums? How are art museums responding to the efforts for more transparency and equity in pay? This issue brief combines research from multiple Ithaka S+R projects with a review of public reports on living wages and pay equity within and outside of the museum field. Ithaka S+R’s research on art museum directors and board members, combined with our three cycles of data collection on art museum staff demographics, give us a wealth of information not only on how senior leaders’ views on compensation have changed, but how compensation might intersect with worker diversity and satisfaction in the art museum field.[11] This brief presents examples of museums that are working to find new sources of recurring revenue, or reduce expenses, in order to raise and standardize their salaries.

Social and economic context

What macroeconomic trends emerged during the pandemic to impact pay in the museum sector? At a national level, roughly 22 million jobs were lost over March and April 2020.[12] Since then, employment has steadily rebounded.[13] While unemployment remains low, wages for the middle classes have not grown enough to match inflation. The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Price Index for February 2023 shows prices up six percent from February 2022.[14] Wages for lower-middle-wage, middle-wage, and upper-middle-wage workers have only risen two to four percent since 2019.[15] Moreover, because average consumption patterns differ based on income and consumer goods experience varying inflation rates, the effects of inflation are felt unevenly across income levels, with low-income groups experiencing the worst effects.[16] These figures add up to a picture of increasing economic insecurity for low- and mid-wage workers across the economy.

The rising costs of everyday living essentials as well as leisure activities have created a gap between cost of living and actual wages, even for those making above minimum wage. The MIT Cost of Living Calculator found that for a family of four with two working adults and two children, the living wage in the United States in 2022 was $25.02 per hour (per adult, working full time), or $104,077.70 per year (combined), before taxes.[17] In the museum context, the positions with the most employees—security and visitor services—do not pay a living wage by this measure.[18] According to the 2022 AAMD Salary Survey, the median salaries for these jobs are $40,000 and $37,400, respectively.[19] This is the case even if we take into account areas where wages might be higher. The AAMD Salary Survey reports that in the Mid-Atlantic region, the 75th percentile of salaries for visitor services associates is $42,400—meaning that only 25 percent of museums pay salaries above this amount. While this is a full $5,000 more annually than the national median for this position, the salary still couldn’t stretch far. In the New York City metro area, the cost of living for a single person with no children is $46,800, according to the MIT Cost of Living Calculator.

The gap between wages and actual costs of living combined with the levels of student debt many cultural workers take on to earn required degrees for the profession has become a focal point in recent labor organizing efforts. While the share of US workers that are members of labor unions has steadily declined since the 1980s, the total number of workers belonging to a union increased from 2021 to 2022.[20] Analysis from the Economic Policy Institute found that interest in unions is also increasing, stating that “between October 2021 and September 2022, the National Labor Relations Board saw a 53 percent increase in union election petitions, the highest single-year increase since fiscal year 2016.”[21] For the museum sector, unionization appears to be an increasingly common strategy. The share of museum workers who are union members is slightly higher than that of the national working population—13 percent compared to 10 percent in 2022.[22] Through an analysis of publicized unionization efforts, we found that 24 museums (6 percent) out of the 370 museums that participated in either the Staff Demographic Survey, Museum Director Survey, or Art Museum Trustee Survey have unions with organizations such as the United Automobile Workers (UAW), Cultural Workers United- American Federation of State and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), United Steel Workers (USW), and the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO).

For museum workers, unionization represents an opportunity to drive systemic change in the cultural sector. As one Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, organizer stated in an interview with Artnet News in 2020, “We are combating the museum model. In the weird public/private hybrid model of the museum, there is seemingly unlimited money made in donations for the building and for artwork, but a millionaire or billionaire is never going to swoop in to provide changes to wage structure or employee safety.”[23]

Workers are also striking at cultural institutions in the United Kingdom for similar reasons as their US counterparts. According to one news account, some museum staff members are struggling to pay their bills, and some have been utilizing food banks.[24] During this year, around 133,000 members of the Public and Commercial Services (PCS) Union have voted to go on strike in 132 UK Government departments, as members have been offered just a two percent pay rise at a time when inflation is around 10 percent.[25] In February, British Museum staff staged a week-long walkout, forcing the museum to close for three days.[26] British Museum staff were joined by staff at the Wallace Collection, Historic England, National Museums Scotland, and the National Museum of Liverpool.[27]

The effects of the pandemic have strained museums’ funds from earned revenue, which often made up the smallest shares of museum budgets before the pandemic.[28] The National Snapshot of COVID-19 Impact on United States Museums survey found that between March 2020 and January 2022, 60 percent of museums experienced revenue losses related to the pandemic.[29] Ithaka S+R’s 2022 Art Museum Director Survey found that 25 percent of art museums had not resumed regular hours and days of operation from before the start of the pandemic.[30] The global decline in museum visits since the pandemic presents a particular challenge to art museums’ ability to raise pay; “earned revenue” from admissions, rentals, and other similar sources are the most flexible sources of funding from which directors can draw.[31] Museums are therefore left in what we have characterized as a revenue/expense bind—shouldered with rising costs, including energy and operations costs on top of new living wage standards, and facing unstable revenue sources. Still, leaders recognize pay equity and living wages as growing priorities. Evidence from our surveys reveals the connections directors see between compensation and employee diversity, recruitment, and satisfaction.

Pay equity and living wages as a DEAI strategy

Equal pay for comparable positions and living wages are two facets of pay equity that our research has studied. Ensuring equal pay for comparable positions involves reviewing and standardizing job descriptions to reduce pay inequality for individuals doing similar work. This is the kind of pay inequality economists and sociologists are studying in examinations of pay gaps based on race and gender, controlling for personal and structural characteristics like age, education, and occupation. The issue of living wages focuses on ensuring that baseline pay keeps up with inflation, costs of living, and requisite education expenses, perhaps reducing inequality between the highest and lowest paid individuals in an organization. Efforts for pay transparency relate to both of these goals; making salary ranges standardized and available is designed to reduce bias in pay across comparable work and can be a source of accountability if organizations’ compensation ranges don’t meet local costs of living requirements. There are also critiques of pay transparency movements; studies have found that implementing pay transparency has mixed relationships with productivity and can lower the bargaining power of individual high-earners.[32]

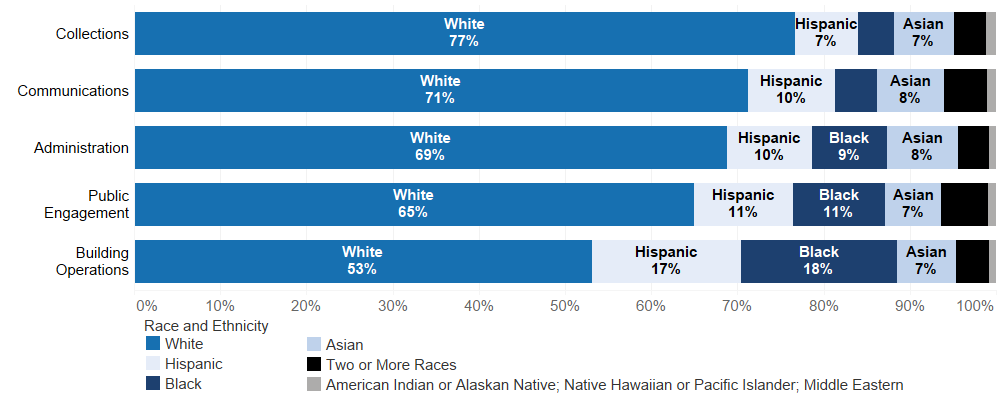

Art museum jobs are lower paid compared to those in other industries that require similar educational investment which, in the US, is often associated with student loan debt.[33] The cost of education can heavily influence a person’s career choices, with many opting for careers that might offer better financial stability or more loan repayment options. Consequently, for people without family wealth, the burden of student loan debt can create a barrier to pursuing a career in the museum field. Due to structural inequalities in the US education system, labor, and housing market, this wealth-based barrier partially explains the predominance of White employees in leadership, conservator, and curator roles in US art museums (Figure 1).[34] Addressing these disparities between the costs of career development with the eventual outcome of available jobs and pay is one piece of the work necessary to ensure that the museum field is reflective of the US population.

Figure 1: Museum role by race/ethnicity, from the 2022 Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey

The 2022 Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey reveals that compensation for the lowest-paid positions in the field also have important implications for racial diversity and equity. Despite steady increases in the representation of POC workers across all museum roles, Black and Hispanic employees are most highly represented in Building Operations and Public Engagement roles, at levels disproportionate to their overall representation in the art museum workforce. Data from the 2021 AAMD Salary Survey show that average salaries for workers in Public Engagement and Building Operations roles are lower than those for Collections, Communications, and Administration roles. In the Public Engagement role, at the lowest end, visitor services associates make $31,000 on average and education assistants make $42,000 on average. At the highest end of the average salary range, directors of education make $88,000. Like the Public Engagement role, Building Operations contains some of the lowest paid positions in the museum. Average salaries range from $40,000 for security officers and $49,000 for associate preparators to $75,000 for chiefs of security and $90,000 for facilities directors.

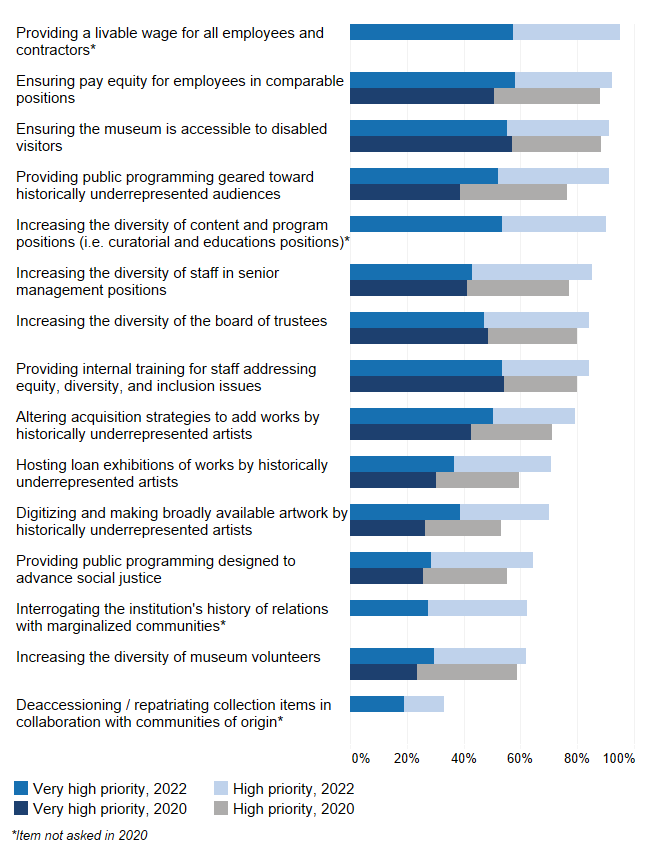

These findings help explain why so many museum directors see compensation as an important diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion (DEAI) issue at their museum. Ninety-five percent of art museum directors said that providing a livable wage for all employees and contractors was a very high or high priority DEAI strategy at their museum. Ensuring pay equity for employees in comparable positions was selected as a very high or high priority DEAI strategy by 92 percent of directors, as seen in Figure 2. These two strategies were seen as very high or high priorities by the highest percentage of directors, followed closely by ensuring the museum is accessible to disabled visitors, providing public programming geared toward historically underrepresented audiences, and increasing the diversity of content and programming positions.

Figure 2: “How much of a priority is each of the following equity, diversity, and inclusion strategies at your museum?” from the 2022 Art Museum Director Survey

While directors were almost unanimous in seeing livable wages and pay equity as important DEAI strategies, there is variation in the directors who viewed livable wages as a very high priority. At the museums that responded to our surveys, on average 36 percent of employees were identified as people of color.[35] At museums that met or exceeded that average, a greater percent of directors (71 percent) said that providing a livable wage for all employees and contractors was a very high priority. Conversely at museums with a lower percentage of POC staff, 57 percent of directors called providing a livable wage a very high priority. Museum directors appear to see issues of compensation as central to their DEAI work, with a possible relationship between staff diversity and prioritizing living wages. In the next section, we’ll explore how pay might be related to ongoing and new challenges in worker recruitment and retention.

Attracting and retaining talent – competitive compensation

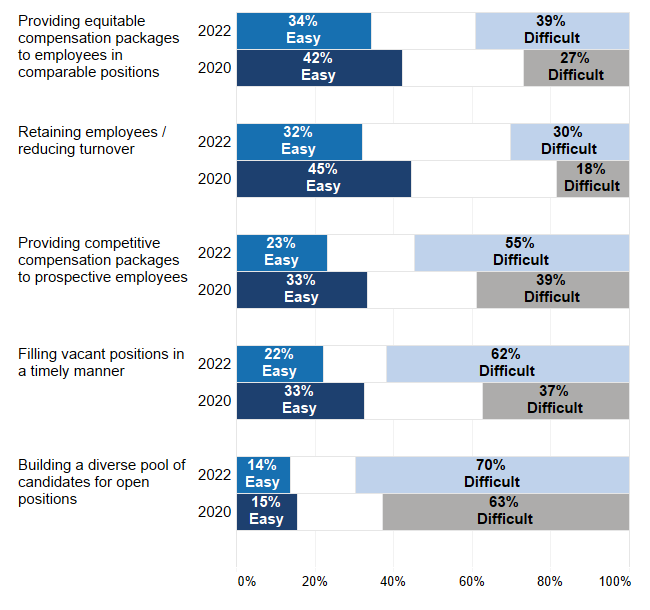

Compensation has historically been a challenge for museum leaders, but the many social forces since the pandemic including the Great Reshuffle, historically tight labor markets, the rising cost of living, and instability around funding—have heightened these challenges. Recruiting and retaining talented workers have important implications for museums’ ability to operate effectively, conserve cultural resources, and continue to offer impactful public programming. To better understand the underlying challenges to staffing, the museum director survey asked directors how easy or difficult they found several activities related to managing staff (Figure 3). Directors saw activities around pay and retaining staff as noticeably more difficult in 2022 than in 2020. In 2020, 27 percent of directors said that providing equitable compensation packages to employees in comparable positions was difficult; this number jumped more than ten points to 39 percent in 2022. Because we are measuring perceptions, this could be the result of new material challenges (such as a more limited budget that limits compensation increases) or a new focus or framing around these issues.

Figure 3: “Presently, in staffing positions in your museum, how easy or difficult are each of the following?” from the 2022 Art Museum Director Survey

Leaders are also facing increased challenges in attracting job candidates. In 2022, 62 percent of directors said that filling vacant positions in a timely manner was difficult, up from 37 percent before the pandemic. Directors likely face many challenges in attracting the right candidates for jobs, as low levels of unemployment decrease the number of people looking for jobs, and nonmonetary priorities like working from home or safety considerations are factoring into job seekers’ decisions. However, in 2022, 55 percent of directors said that providing competitive compensation packages to prospective employees was difficult, up from 39 percent in 2020. The salaries museums are able to provide may play an important role in their staffing challenges.

The increased difficulty in providing equitable and competitive compensation may also impact leaders’ abilities to retain current employees. Retaining employees and reducing turnover was seen as difficult by 30 percent of directors in 2022, up from 18 percent in 2020. Again, there are likely many reasons individuals consider when making the choice to voluntarily leave their museums. At the same time, the survey findings reveal that 64 percent of directors continue to see compensation as one of the common reasons behind employees voluntarily leaving their museum. Similarly, a survey of museum workers and students during the pandemic found that 20 percent of respondents anticipated no longer working in the field in the next three years.[36] Compensation was an important issue for respondents; 59 percent of all respondents and 78 percent of students saw compensation as a potential barrier to remaining in the museum sector.

Directors’ ability to retain staff intersects with employee diversity. The 2022 Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey found that POC staff made up a much larger percentage of employees hired since 2020 than they did in years before 2020, resulting in a more diverse workforce overall in 2022 than in the 2020 and 2018 survey cycles. Retaining these new employees will be crucial to ensuring that this growth in diversity is just and sustainable. As directors and staff have identified, compensation is one important aspect of keeping people employed in the organization and profession.

Solving the resource bind

For leaders that want to address pay equity and living wages in their museums, the biggest challenge, even more so in the recent inflationary environment, is often finding the funding to support a permanent increase in compensation. Museums are able to devote greater resources to compensation through one of two basic strategies—finding new revenue streams, and/or making difficult reductions in expenses. In some cases, expenses are reduced through employee downsizing, leaving a museum with a smaller headcount of more equitably compensated employees. As leaders consider pursuing one or both of these strategies to raise employee pay, museum boards can be powerful resources for fundraising and prioritizing staff in museum strategy.

The important role that boards of trustees can have in leading pay equity discussions emerged in Ithaka S+R’s research on art museum trustees and in recent accounts of museum compensation reviews. The board of trustees at the Oakland Museum was actively involved in the museum’s work to become an anti-racist museum committed to organizational transparency and pay equity.[37] At the Filoli Historic House and Gardens, the board engaged in a comprehensive strategic plan that made attracting and retaining staff its core goal.[38] These strategic transformations at the board level resulted in compensation reviews that used living wages—based on cost of living and educational requirements—as the starting point for salary raises. At the Bakken museum, a pay standardization and transparency initiative also benefited from board support and advising.[39] Though recent, these changes indicate that raising pay and introducing more transparency around compensation has a relatively immediate effect on employee retention and morale. At Filoli, turnover fell from 50 percent to 8 percent, and at the Bakken, staff surveys show that more employees understand how pay is determined and believe they are paid fairly.

Of course, museums have to find ways to cover new salary costs. As the executive vice president at the Bakken Museum described, “we do not have expenses that we can ‘reprioritize,’” instead, revenue was brought in through raising prices.[40] At Filoli, which already relied on earned revenue for the majority of its budget, the museum increased prices for both admissions and membership and invested in its group tours programming.[41] The Oakland Museum was able to ensure that no employee earned below $51,000 a year by laying off some of its staff. As one trustee explained, “we knew that our budget would only go so far. And that, ultimately, we would have to entertain downsizing. …But in doing so, we knew that it would raise the level of income for everybody at the institution.”[42]

Each one of these approaches shows the tradeoffs that leaders must face as they navigate these decisions in the context of the growing calls for compensation reform. Following years of advocacy from staff, our survey findings make it clear that art museum directors recognize the need for more equitable pay in the industry. However, identifying a priority is just the beginning. In addition to the strategies of establishing base-level living wages and bringing transparency and standardization to job titles and pay, museum leaders will need to find ways to solve their revenue/expense bind to fund compensation changes. Ultimately, it is a leadership and board-level decision whether living wages and salary equity are realized as foundational values in the museum sector.

Endnotes

- “The 118th Congress NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist National Poll,” Marist Poll, https://maristpoll.marist.edu/polls/the-118th-congress.“Quick Facts About State Salary Range Transparency Laws,” Center for American Progress, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/quick-facts-about-state-salary-range-transparency-laws. ↑

- Liam Sweeney, “How Will Museums Live Up to their Solidarity Commitments?” Ithaka S+R, 12 June 2020, https://sr.ithaka.org/blog/how-will-museums-live-up-to-their-solidarity-commitments/. ↑

- “The 100 Most Popular Art Museums in the World—Who Has Recovered and Who Is Still Struggling?” The Art Newspaper, 27 March 2023, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2023/03/27/the-100-most-popular-art-museums-in-the-worldwho-has-recovered-and-who-is-still-struggling. ↑

- “About,” Art + Museum Transparency, https://www.artandmuseumtransparency.org/about. ↑

- “Advocacy,” National Emerging Museum Professionals Network, https://nationalempnetwork.org/advocacy/. ↑

- Laura Benshoff, “Strike by Philadelphia Museum of Art Workers Shows Woes of ‘Prestige’ Jobs,” NPR, 8 October 2022, https://www.npr.org/2022/10/07/1127400793/what-a-strike-at-a-philadelphia-museum-reveals-about-unionizing-cultural-institu. ↑

- “Museum Jobs – AAM JobHQ,” American Alliance of Museums, accessed 12 April 2023, https://aam-us-jobs.careerwebsite.com?site_id=8712; “Pay Transparency,” NYC Human Rights, accessed 12 April 2023, https://www.nyc.gov/site/cchr/media/pay-transparency.page. ↑

- “Archivists, Curators, and Museum Workers : Occupational Outlook Handbook,” US Bureau of Labor Statistics,” accessed 12 April 2023, https://www.bls.gov/ooh/education-training-and-library/curators-museum-technicians-and-conservators.htm#tab-7. ↑

- Liam Sweeney and Joanna Dressel, “Art Museum Director Survey 2022: Documenting Change in Museum Strategy and Operations,” Ithaka S+R, 27 October 2022, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.31777. . ↑

- Amy Haimerl, “What Keeps U.S. Art Museums Running—and How Might the Pandemic Change That?,” ARTnews, https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/united-states-art-museum-financing-1234584930/. ↑

- The reports we draw from for this issue brief include: Liam Sweeney, Deirdre Harkins, Celeste Watkins-Hayes, and Dominique Adams-Santos, “The BTA 2022 Art Museum Trustee Survey: The Characteristics, Roles, and Experiences of Black Trustees,” Ithaka S+R, 16 November 2022, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.317881; Liam Sweeney, Deirdre Harkins, and Joanna Dressel, “Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey 2022,” Ithaka S+R, 16 November 2022, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.317927; and Liam Sweeney and Joanna Dressel, “Art Museum Director Survey 2022: Documenting Change in Museum Strategy and Operations,” Ithaka S+R, 27 October 2022. https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.317777. ↑

- “The Employment Situation-April 2020,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/empsit_05082020.pdf. ↑

- “The Employment Situation-February 2023,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/empsit_03102023.pdf. ↑

- “Consumer Price Index up 0.4 Percent over the Month, 6.0 Percent over the Year, in February 2023 : The Economics Daily,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, 20 March 2023, https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2023/consumer-price-index-up-0-4-percent-over-the-month-6-0-percent-over-the-year-in-february-2023.htm. ↑

- Elise Gould and Katherine deCourcy, “Low-Wage Workers Have Seen Historically Fast Real Wage Growth in the Pandemic Business Cycle: Policy Investments Translate into Better Opportunities for the Lowest-Paid Workers,” Economic Policy Institute, 23 March 2023, https://www.epi.org/publication/swa-wages-2022/. ↑

- Joshua Klick and Anya Stockburger, “Inflation Experiences for Lower and Higher Income Households : Spotlight on Statistics,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, December 2022, accessed 12 April 2023, https://www.bls.gov/spotlight/2022/inflation-experiences-for-lower-and-higher-income-households/home.htm. ↑

- “Living Wage Calculator,” MIT, accessed 12 April 2023, https://livingwage.mit.edu/articles/103-new-data-posted-2023-living-wage-calculator. ↑

- Liam Sweeney, Deirdre Harkins, and Joanna Dressel, “Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey 2022,” Ithaka S+R, 16 November 2022, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.317927. ↑

- “Salary Survey 2022,” Association of Art Museum Directors, 6 September 2022, https://aamd.org/our-members/from-the-field/salary-survey-2022. ↑

- “Union Members Summary – 2022 Results,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor, accessed 12 April 2023, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/union2.pdf. ↑

- Heidi Shierholz, Margaret Poydock, and Celine McNicholas, “Unionization Increased by 200,000 in 2022: Tens of Millions More Wanted to Join a Union, but Couldn’t,” Economic Policy Institute, 19 January 2023, https://www.epi.org/publication/unionization-2022/. ↑

- “Union Membership and Coverage Database,” Union Stats, accessed 12 April 2023, https://unionstats.com/. ↑

- Catherine Wagley, “Museum Unions Aren’t Just Demanding Higher Pay. They’re Also Fundamentally Questioning the Way Their Institutions Work,” Artnet News, 2 March 2020, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/museum-unions-voluntary-recognition-1790097. ↑

- Barry Caffrey and Chelsea Coates, “PCS Union Staff at British Museum Strike over Half Term,” BBC News, 14 February 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-london-64636374. ↑

- Geraldine Kendall Adams, “Museum and Heritage Workers to Join Public Sector Strike,” Museums Association, 14 March 2023, https://www.museumsassociation.org/museums-journal/news/2023/03/museum-and-heritage-workers-to-join-public-sector-strike/. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Tom Seymour, “British Museum Staff to Strike as Cultural Workers across UK Take Industrial Action—Including during School Holiday,” The Art Newspaper, 30 January 2023, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2023/01/30/british-museum-staff-to-strike-as-cultural-workers-across-uk-take-industrial-actionincluding-during-busy-half-term-holiday. ↑

- Liam Sweeney and Joanna Dressel, “Art Museum Director Survey 2022: Documenting Change in Museum Strategy and Operations,” Ithaka S+R, 27 October 2022, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.317777. ↑

- “National Snapshot of COVID-19 Impact on United States Museums,” American Alliance of Museums, 8 February 2022, https://www.aam-us.org/2022/02/08/national-snapshot-of-covid-19-impact-on-united-states-museums-fielded-december-2021-january-2022/. ↑

- Liam Sweeney and Joanna Dressel, “Art Museum Director Survey 2022: Documenting Change in Museum Strategy and Operations,” Ithaka S+R, 27 October 2022, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.317777. ↑

- Amy Haimerl, “What Keeps U.S. Art Museums Running—and How Might the Pandemic Change That?,” ARTnews, https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/united-states-art-museum-financing-1234584930/. ↑

- Tomasz Obloj and Todd Zenger, “Research: The Complicated Effects of Pay Transparency,” Harvard Business Review, 8 February 2023, https://hbr.org/2023/02/research-the-complicated-effects-of-pay-transparency. ↑

- The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that the median salary for curators is $56,220, while the median salary for all workers with a Master’s degree is $77,750. “Museums, Historical Sites, and Similar Institutions: NAICS 712,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed 13 April 2023, https://www.bls.gov/iag/tgs/iag712.htm#earnings. “Occupations that Need More Education for Entry are Projected to Grow Faster Than Average,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed 13 April 2023, https://www.bls.gov/emp/tables/education-summary.htm. According to the Education Data Initiative, 66 percent of graduate students borrow federal loans, and the average student loan debt for graduate school alone ranges from $67,221 to $76,182. “Student Loan Debt Statistics [2023]: Average + Total Debt,” Education Data Initiative, accessed 13 April 2023, https://educationdata.org/student-loan-debt-statistics; “Average Graduate Student Loan Debt [2023]: For Master’s & PhD,” Education Data Initiative, accessed 13 April 2023, https://educationdata.org/average-graduate-student-loan-debt. ↑

- Liam Sweeney, Deirdre Harkins, and Joanna Dressel, “Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey 2022,” Ithaka S+R, 16 November 2022, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.317927. ↑

- The staff demographic survey instrument asked the administrator who completed the survey to identify each staff member’s race and ethnicity. In our analysis, we created a new variable that considers all individuals identified as American Indian or Native American, Asian, Black, Hispanic of any race, Middle Eastern, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, or Two or More Races as people of color and all individuals identified as White, not Hispanic as White. The report includes detailed representation information for this grouped variable as well as each race-ethnicity identity. ↑

- “Measuring the Impact of COVID-19 on People in the Museum Field – American Alliance of Museums,” American Alliance of Museums, 13 April 2021, https://www.aam-us.org/2021/04/13/measuring-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-people-in-the-museum-field/. ↑

- Liam Sweeney, Deirdre Harkins, Celeste Watkins-Hayes, and Dominique Adams-Santos, “The BTA 2022 Art Museum Trustee Survey: The Characteristics, Roles, and Experiences of Black Trustees,” Ithaka S+R, 16 November 2022, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.317881. ↑

- Kara Newport, “Museums and the Living Wage: How Filoli Developed a Bold Pay Equity Initiative,” Center for the Future of Museums Blog, American Alliance of Museums, 17 August 2022, https://www.aam-us.org/2022/08/17/museums-and-the-living-wage-how-filoli-developed-a-bold-pay-equity-initiative/. ↑

- Joe Imholte, “Building Salary Equity at the Bakken Museum,” Center for the Future of Museums Blog, American Alliance of Museums, 2 June 2022, https://www.aam-us.org/2022/06/02/building-salary-equity-at-the-bakken-museum/. ↑

- Joe Imholte, “Building Salary Equity at the Bakken Museum,” Center for the Future of Museums Blog, American Alliance of Museums, 2 June 2022, https://www.aam-us.org/2022/06/02/building-salary-equity-at-the-bakken-museum/. ↑

- Kara Newport, “Museums and the Living Wage: How Filoli Developed a Bold Pay Equity Initiative,” Center for the Future of Museums Blog, American Alliance of Museums, 17 August 2022, https://www.aam-us.org/2022/08/17/museums-and-the-living-wage-how-filoli-developed-a-bold-pay-equity-initiative/. ↑

- Liam Sweeney, Deirdre Harkins, Celeste Watkins-Hayes, and Dominique Adams-Santos, “The BTA 2022 Art Museum Trustee Survey: The Characteristics, Roles, and Experiences of Black Trustees,” Ithaka S+R, 16 November 2022, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.317881. ↑