The BTA 2022 Art Museum Trustee Survey

The Characteristics, Roles, and Experiences of Black Trustees

Foreword

The Black Trustee Alliance for Art Museums (BTA) was established in 2021 to transform art museums into more equitable spaces of cultural engagement by harnessing the power of Black trustees.

With a community of nearly 300 members and followers, BTA is helping Black trustees lead the institutions they steward toward an inclusive future that reflects the best of the world of art and culture in its entirety. BTA is committed to dismantling barriers that block the entry and advancement of Black staff and leadership in the cultural field; to changing the underrepresentation of Black narratives in exhibitions, collections, and programming; and to increasing the patronage of minority-owned service providers by cultural organizations. BTA’s approach to helping art museum trustees address these issues is multifold, prioritizing the commissioning of original research and supporting affiliates’ research to develop data-driven tools that enable our members to be more effective in leading the transformation of their institutions. One of our first major initiatives was conducting this study of the individuals who have been advocating for that change to date: Black trustees.

BTA’s inaugural Art Museum Trustee Survey Report is the first to capture the unique position of a Black trustee. While one can more easily observe the low numbers of Black museum trustees, the extent of the racial disparity at the board level has not yet been clearly articulated or documented otherwise. In 2017, the American Alliance of Museums published a report that included one of the few existing data points illustrating how much work needed to be done. It found that nearly 50 percent of museum boards lacked even one person of color.[1] In addition to increasing the representation and participation of Black trustees, one of our goals is to help our members become more effective advocates for change; therefore it is critical for us to keenly understand their day-to-day experiences. We can then use those findings to generate research, resources, and tools dedicated to building and strengthening the community even further.

With generous support from the Mellon Foundation, we partnered with Ithaka S+R and hired our first research and data fellow to collect and record demographic information by fielding a survey to art museum trustees across the country; a call to which more than 900 responded. Following this initial survey, our research team conducted in-depth interviews with 20 Black trustees about their experiences serving on art museum boards. From that group, we have highlighted three trustee perspectives in this report, zeroing in on institutions that have proactively addressed issues of diversity, equity, access, and inclusion among their board, staff, and visitors. Close reading of these accounts helps demonstrate what’s possible when museum leaders make a genuine and concerted effort to put equity concerns at the forefront of their institutional mission. Our hope is that these insights can be applied to other institutions advancing strategies to do the same.

The Art Museum Trustee Survey produced many valuable insights, sentiments, and takeaways. One insight in particular helps explain why so few Black people become museum trustees: they simply aren’t approached to join. Museum directors or trustees invite individuals they already know to join their boards. This finding confirms what we have noticed anecdotally: museums seek out new members through familiar—and racially stratified—social and professional networks. Unless we create broader and more accessible pipelines for Black trusteeship, our boards will remain as predominantly White as they are today. Equipped with Ithaka S+R’s research results, we offer Ten Evidence-based Strategies for Cultivating DEAI Values in the Boardroom as we work to transform the systems that have contributed to the racial homogeneity of our art museum boards.

Looking ahead, we understand the importance of establishing a benchmark from which we can measure changes in the field. Creating an equitable institution takes time. And while our overall objective is clear, the way to get there is not—and rightfully so, since no two institutions operate the same way. It is essential that we bring diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion into museums. We hope that institutions view this study as a key reference as they strategically map their journey toward justice. Following the publication of this inaugural report, we will continue to provide Black trustees with resources to help their respective institutions create a viable path towards greater diversity. Now is the time to bring about the change we want to see.

– Black Trustee Alliance for Art Museums

How to Use this Report

This report is a tool intended to relate the characteristics, experiences, and roles of Black trustees currently serving on art museum boards. By blending quantitative survey data and qualitative interviews, we hope to present readers with several ideas to spark discussion within their museum boards. The survey data is designed to give museum directors and trustees a broad overview of the demographic characteristics and general experiences of museum trustees. We recognize the broad diversity, not only of the Black trustees who participated in this study, but also the museums and communities that they represent. Region, culture, budget, and size are some of the many factors that may affect how the findings of this report are applied. These trends should encourage trustees to consider how their boards and board experiences compare; what issues resonate; and what dynamics and nuances, spoken and unspoken, might shape the inner workings of their boards. The trustee perspectives, representing summaries of in-depth interviews conducted with trustees, are designed to capture some of the mechanisms, useful practices, and lessons learned from museum trusteeship.

It is also important to note that this report highlights the perspectives of Black trustees who remain engaged in their museum boards and committees and does not include the reflections or sentiment of trustees who are no longer serving on art museum boards. We hope that boards will draw out themes and craft questions for discussion inspired by what they read in the report, and that this might encourage boards to reflect and reimagine how they work together.

Executive Summary

The Black Trustee Alliance for Art Museums (BTA) has partnered with Ithaka S+R to examine the experiences and demographics of art museum trustees from museums in the US, Canada, and Mexico. Through a shared interest in representation in the arts, BTA and Ithaka S+R fielded the Art Museum Trustee Survey to board members in the fall of 2021. This survey was distributed to 287 art museums across North America. We had one or more respondents from 134 institutions, resulting in a 47 percent institutional response rate. For 83 of these museums at least one Black trustee responded. Following the survey, researchers conducted interviews with 20 Black art museum trustees, which provided valuable qualitative evidence of their experiences as board members. This report draws on survey analysis from over 900 respondents, as well as a synthesis of trustee interviews.

The report investigates the characteristics, roles, and experiences of Black trustees in North American art museums: characteristics include demographics, professional backgrounds, and interests; roles include contributions and committee assignments; and experiences include reflections on board and museum culture, onboarding experiences, and navigating controversies.

Key Findings from the Quantitative Study

- Black trustees tend to be younger and are less likely to show indications of intergenerational wealth;

- Black trustees are more likely to hold PhDs and professional degrees than White board members;

- Black trustees, like non-Black trustees, are identified for board service primarily through pre-existing relationships with the museum director or other trustees;

- Black trustees have a high representation on Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Governance and/or Nominating committees, and a lower representation on Investment, Director’s Search, and Collections/ Acquisitions committees;

- Black trustees are less likely than White board members to have family members that serve/served on art museum boards, but a third have/had family members on other nonprofit boards;

- Across all race categories, including Black trustees, the majority of respondents are highly satisfied with their board experience. However, Black trustees were more likely than their fellow trustees to report a negative climate in the boardroom;

- The diversity of a trustee’s network is an important strategic consideration when recruiting for nomination to the board.

This report unpacks the significance of these key findings and highlights the implications they have for the boardrooms of art museums. These findings reflect a moment in time, creating a benchmark from which change can be measured in future survey and interview cycles. Senior leadership and current board members may find these aggregate statistics and qualitative responses useful when considering how to nominate trustees and cultivate inclusive and equitable climates in the boardroom.

We would like to thank the following contributors, who have aided the development of this instrument and report: BTA executive director Brooke A. Minto, program managers Izzy Greene and Samantha Fleurinor, BTA board members Victoria Rogers and Raymond J. McGuire, research advisors, Franklin Sirmans, director of the Pérez Art Museum Miami, and Naomi Beckwith, chief curator of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

We would also like to thank Hallie S. Hobson for her work in establishing a research relationship between BTA and Ithaka S+R, Kara Bledsoe for her contributions and project management during the first stages of this project, and our Ithaka S+R colleagues Nicole Betancourt, for her help administering the survey, and Roger Schonfeld, Oya Rieger, Mark McBride, and Kimberly Lutz for their support with the final report.

And finally, we are grateful to the 20 trustees who took part in the interview portion of this project. A special thanks to Dana King, Oakland Museum of California trustee emeritus, Alicia Wilson, vice president of the board at The Walters Art Museum, and Darrianne Christian, board chair at Newfields, for allowing us to highlight their experiences and perspectives. And thank you to Oakland Museum of California director, Lori Fogarty, The Walters Art Museum director Julia Marciari-Alexander, and Newfields CEO Dr. Colette Pierce Burnette, for their support.

Characteristics of Respondents

One of the primary goals of the survey of art museum trustees was to learn more about the identities of Black trustees in the field, contextualized in relation to their non-Black peers. To this end, the survey asked a series of questions about who these trustees are and how they were nominated to the board of a museum. Table 1 shows the number of responses received, organized by race.

Table 1: Art Museum Trustee Respondents by Race

As Table 1 shows, 168 respondents were Black trustees. Throughout this report, the data shows responses from trustees grouped into three categories: Black, White, and Non-Black People of Color (NBPOC).[2] Based on the number of respondents, as well as an interest to better contextualize Black experiences and perspectives, this approach to data categorization is well suited for comparative analysis. Unfortunately, response rates for individual racial and ethnic groups other than White and Black are too small to analyze without this aggregation.

The respondents included 94 Black female trustees (57 percent), 72 Black male trustees (43 percent), one Agender individual, and one respondent who declined to state their gender. There was a similar female majority ratio in the overall survey population of 926 responses, with 523 women (59 percent) and 368 men (41 percent) represented. Additionally, among total respondents, we received submissions from the following gender identities: one agender, one gender non-conforming, one non-binary. Thirty-one respondents selected “I prefer not to answer,” and two selected, “Another option not listed here.” This representation tracks with broader trends in staffing within the cultural sector.[3]

Age Range

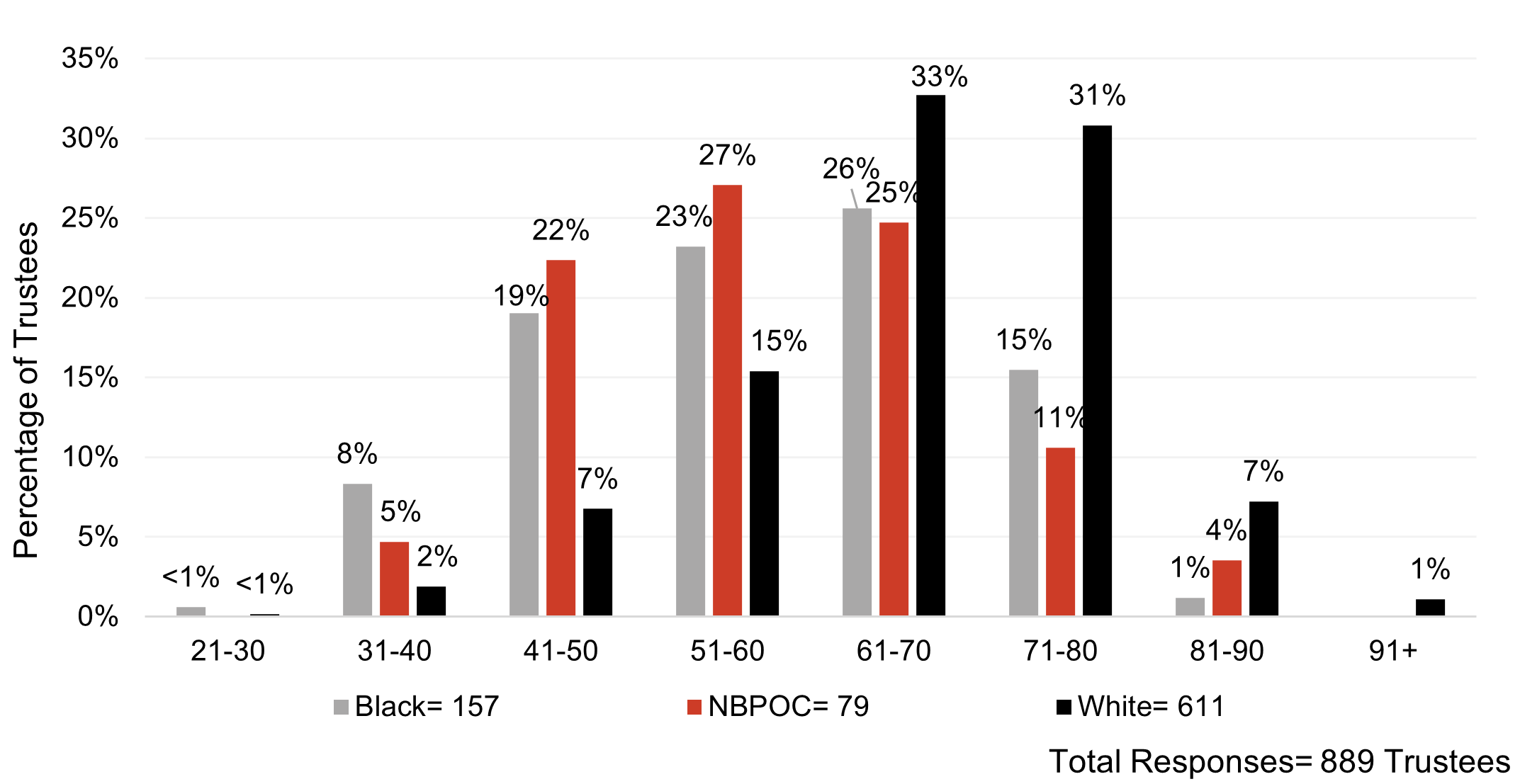

Analyzing trustee demographics by year of birth reveals that Black respondents are, on average, ten years younger than their White counterparts (Figure 1). The average year of birth of Black trustees is 1963, while White trustees have an average year of birth of 1953. The percentage of Black trustees under the age of 50 is 26 percent, while the percentage of White trustees under the age of 50 is 8 percent.

Figure 1: Age Range by Race

The data on age reveals several insights. First, NBPOC follow a similar age pattern to Black trustees. This likely reflects more recent efforts to diversify museum boards. Second, this difference in age will have a meaningful impact in board composition over time if museums are able to retain their trustees of color. As younger trustees advance in their careers, grow their wealth, and retire, they are likely to have more time and resources to devote to the museum. Third, further discussion in this report suggests there is a meaningful difference in the experiences of younger trustees who work full time and have achieved their trustee status through their current and more recent professional accomplishments, as compared to older trustees who are no longer working. Museum leaders should be aware that these dynamics have potential to produce generational tensions in the boardroom, both in the form of ageism and the discrediting of younger board members. These findings demonstrate a potential for museum boards to grow more diverse over time.

Figures 2-4 reflect three questions that serve as proxies for socioeconomic status and generational wealth: whether the trustee is a first-generation college student; the trustee’s annual gross income; and whether the trustee has or had a parent or family member on the board of another museum or non-profit organization.

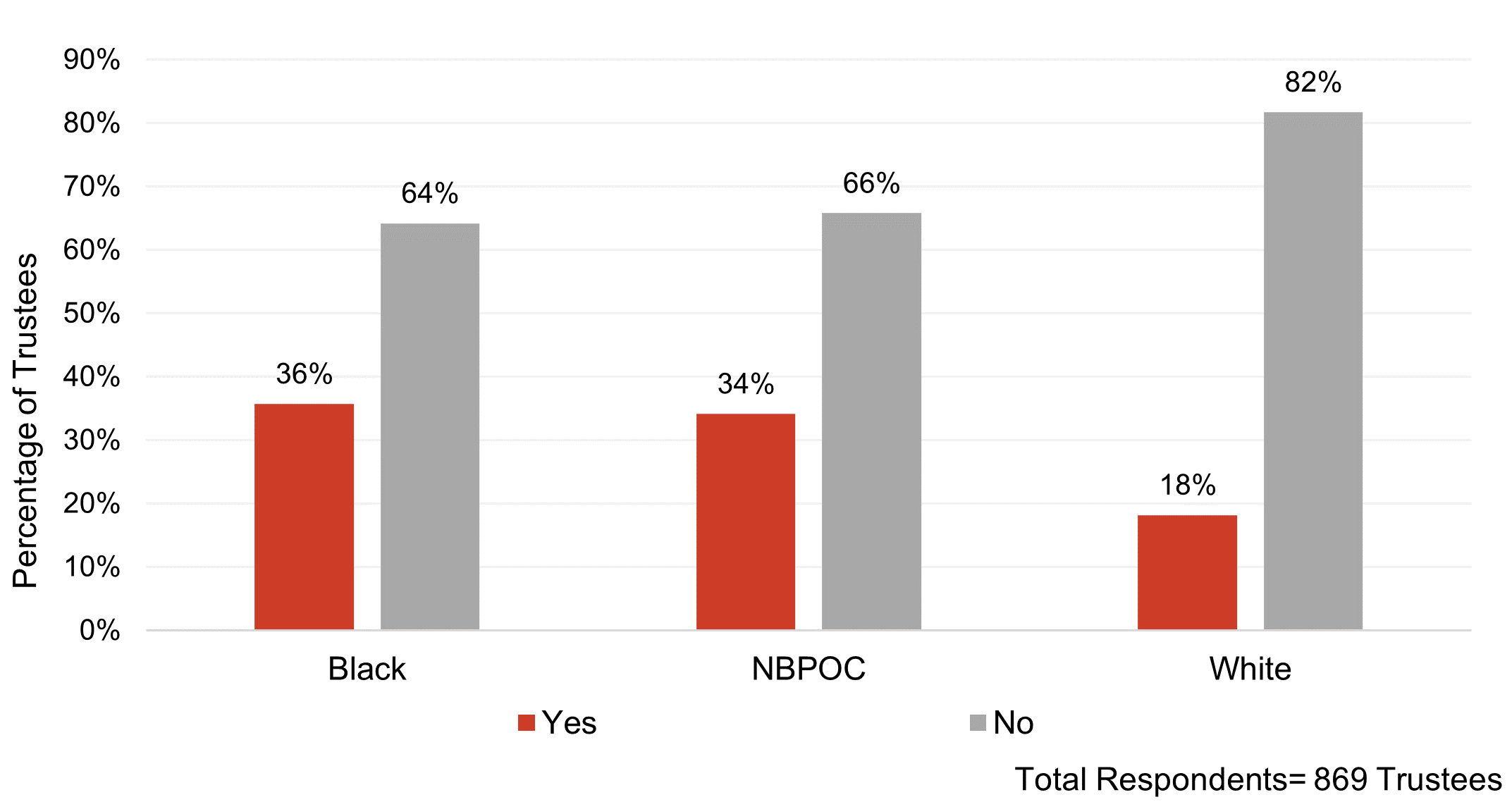

First-Generation College Student

Thirty-six percent of Black respondents reported that they are first-generation college students, whereas 18 percent of White trustees are first-generation and 34 percent of NBPOC are first-generation college students (Figure 2).

Figure 2: First Generation College Student

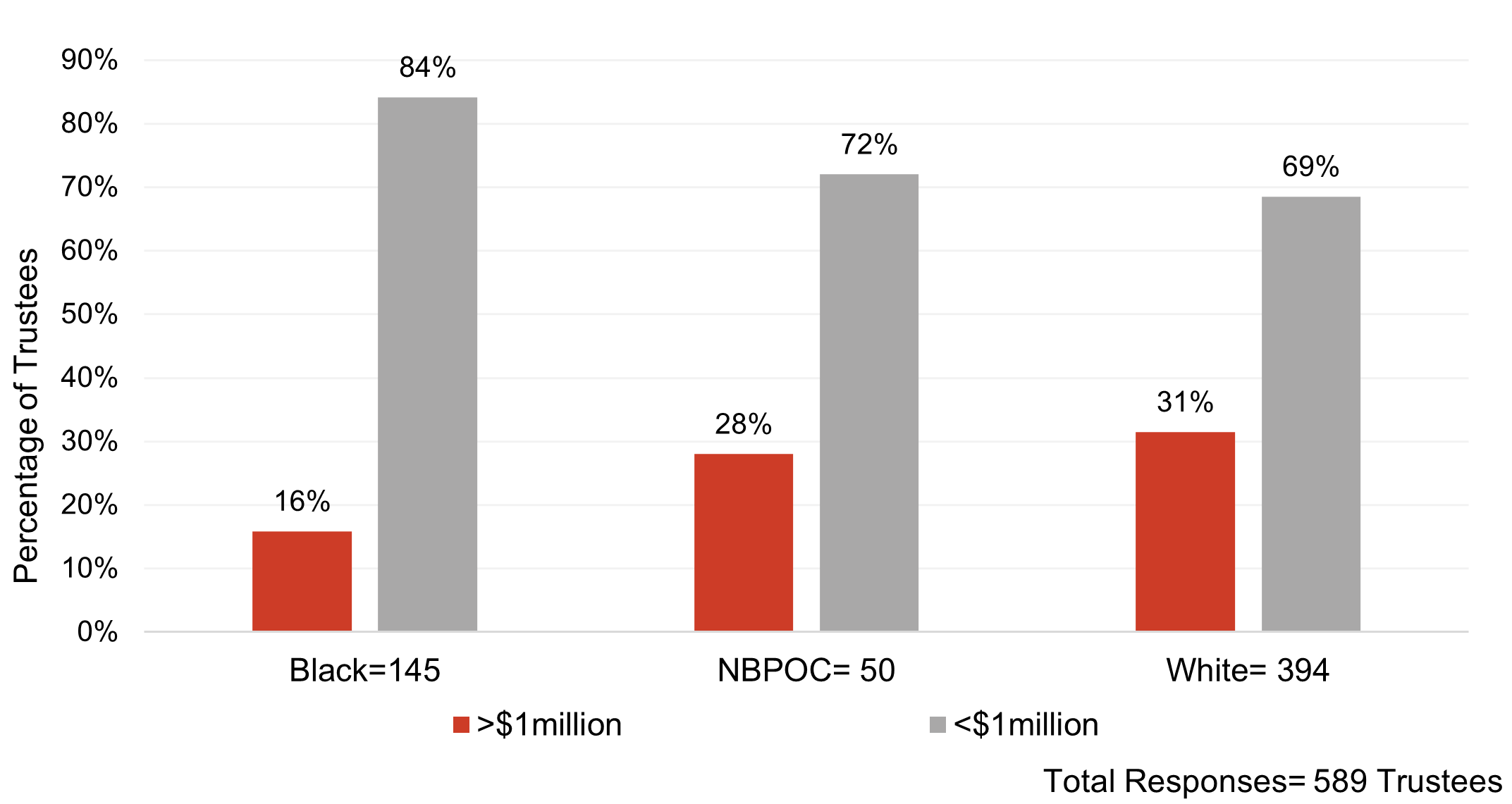

Income

Based on the distribution of responses, we have grouped respondents’ incomes based on whether they reported a salary or household income of more than or less than one million dollars.[4] Thirty-one percent of White respondents reported income over one million dollars annually, while 16 percent of Black respondents reported income greater than one million dollars a year—a 15 percentage point difference. NBPOC trustees fall in the middle of this range, with 28 percent reporting under one million dollars of household income, and 72 percent reporting income above that threshold (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Annual Household Income Distribution by Race

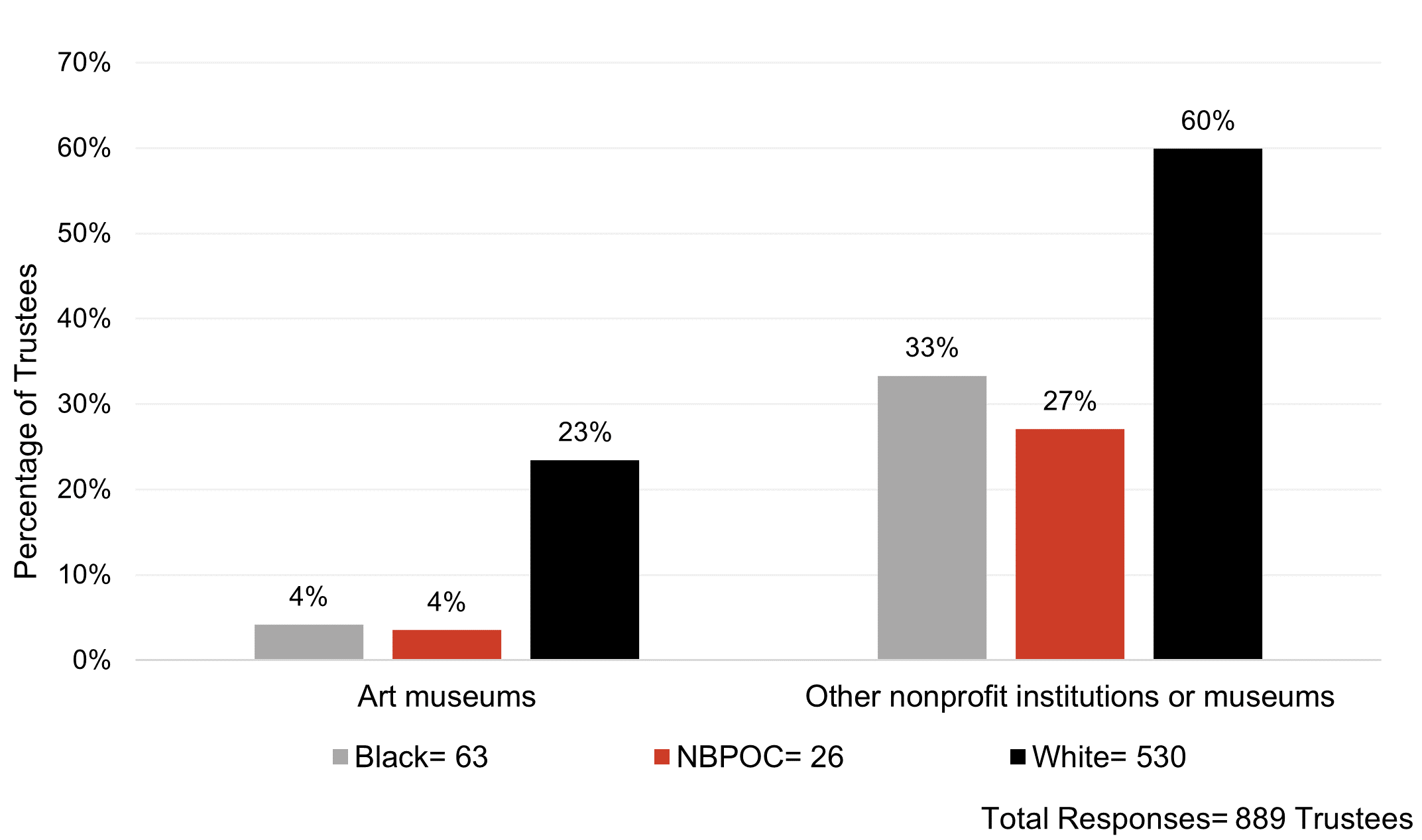

Family member on a board

Respondents were asked to indicate whether they had a family member who was part of a board of either an art museum or other non-profit. Only four percent of Black trustees, as well as NBPOC trustees, had family members on art museum boards, while 33 percent of Black trustees and 27 percent of NBPOC trustees had family members on boards of other non-profits, or other types of museums (Figure 4). In contrast, 23 percent of White trustees reported having family members on art museum boards and 60 percent reported having family members on other non-profits or other museum boards. This aggregate data reflects the generational relationship to trusteeship that some respondents referenced as a source of concern in free text responses. One White trustee who indicated that he was considering leaving a museum board explained that he was motivated by a desire, “To encourage change and new perspectives. To help the museum move away from family legacy.”

Figure 4: Family Members on Nonprofit Boards by Race

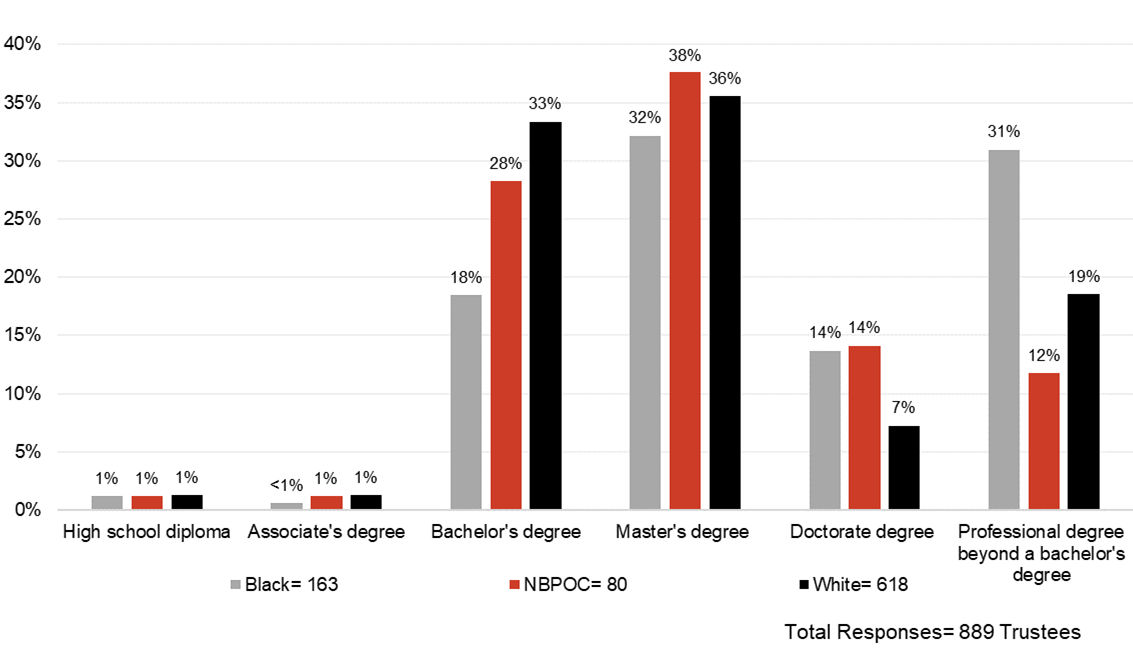

Education

Respondents were also asked to report their highest level of education. When comparing racial groups by education, we found that Black trustees were more likely to hold professional degrees (MBAs, JDs, MD, etc.) than their White and NBPOC counterparts (Figure 5). Additionally, 14 percent of both Black and NBPOC trustees hold PhDs, compared to 7 percent of White trustees. Black women were more likely than Black men to hold PhDs or professional degrees (45 women, and 29 men).

Figure 5: Highest Level of Education by Race

As the data on income, whether trustees were a first-generation college student, and whether their family members have also served on boards reveal, Black trustees in the aggregate appear less likely to have inherited wealth. They are more likely to be working age and highly professionalized. In the following sections we will explore how these characteristics shape the roles and experiences of Black trustees.

Trustee Nomination and Roles

In order to better understand how Black trustees’ nomination processes unfold relative to their fellow trustees, respondents answered questions about how and why they were selected. Studying the collective survey responses of Black trustees, and comparing them to all trustee responses, reveals how Black trustees are engaged by museums and what their experiences are like when transitioning onto museum boards. Additional evidence gathered through interviews allows for added insights about these experiences.

In many cases, methods of board nominations have followed a model of convenience, relying heavily on tapping networks to recruit new members, rather than identifying the skills and backgrounds that would best serve the institution. As a director of a small regional art museum once shared, most of their board members have one primary characteristic in common: their children all attend the same school.[5]

A major challenge with this model of nomination is that social networks can tend toward homogeneity. This recruitment model has in many cases failed to produce diverse boards, creating organizational challenges in the most influential positions of the museum. As the 2017 BoardSource report commissioned by the American Alliance of Museums found, “Museum directors and board chairs believe board diversity and inclusion are important to advance their missions but have failed to prioritize action steps to achieve it […] almost half of museum boards (46 percent) are all white, i.e., containing no people of color.”[6]

Why were they selected?

Survey respondents were asked to provide free text responses answering why they thought they were invited to join the board, why they agreed to join the board, whether they ever considered leaving the board, and, if so, why they considered departing. Black trustees frequently reported that they believed they were selected in order to diversify the museum board and bring improved community engagement to the museum. Non-Black POC trustees also recognized diversifying the board as a primary driver for their nominations. Additionally, in some instances, trustees reported that their expertise in the arts and the academy were important factors as well. By contrast, White trustees commonly cited their philanthropic work or professional experience when answering why they were nominated to the board.

Diversifying the Board

The frequency with which diversification was cited as the primary reason for nomination by both Black and NBPOC trustees (and in some cases White women) speaks to one of the challenges boards face when they are in the early stages of diversification; POC trustees recognize that their racial/ethnic identities are a primary motivation for their nomination. If these boards were already diverse, POC respondents would likely identify a greater variety of reasons behind their board nominations. Among the 20 Black trustees interviewed for this report, eight described that the need to diversify the board was a primary reason that they were asked to join.

One trustee shared a perspective that the lack of diversity on museum boards has less to do with a lack of qualified candidates than a failure of the museum to make a case for the social good of the museum to potential candidates. The biggest problem they faced in diversifying the board was in communicating the importance of museums: “People looking to make contributions in the nonprofit sector tend to focus on measurable and immediate impact. When given the choice to financially support an art museum, or marginalized communities, eligible people of color tend to choose the latter,” this trustee shared.

Another interviewee mentioned initially declining their museum’s invitation to join the board, and it wasn’t until the museum came under new leadership that they finally accepted. Under new leadership, they felt that the museum was going in the right direction toward diversification. But this trustee specified that he would not join unless the director brought additional trustees of color onto the board.

I declined when I was first asked, because I didn’t believe in the direction of the leader at the time. So there was a leadership change. Our current director came on board, and he was saying the right things. He had reached out to me and asked if I would consider joining, and I said, “No, I need to see what you do first.” And so I gave it about a year. And he came back to me, he said, “How am I doing?” And I said, “You’re alright.” He asked if I would consider being a trustee. And I said to him, “I’m happy to be considered, but I don’t want to come on by myself.” And he said, “Okay, I thought you would say that. We have a couple other trustees of color that we’re considering.” I said, “Well, when they say yes, come back to me.” And so they said, yes. And so three of us joined at the time.

This trustee’s retelling exemplifies the importance of the director’s leadership of the museum, which impacts the recruitment of trustees of color to the board. This director helped develop a strategic plan which centered the goal of making the museum a more welcoming place for all visitors and adopted a cohort-based approach to recruitment.

However, upon joining the board, this trustee went to lunch with a fellow board member whom they already knew. It was there that our interviewee was advised “Not to say anything for three years.” This exchange revealed to the interviewee that this kind of board culture would silence newcomers, who were more likely to be younger and people of color. For this trustee, joining with other people of color, or fellow disruptors of the status quo, would be essential for emotional support in a not very welcoming space.

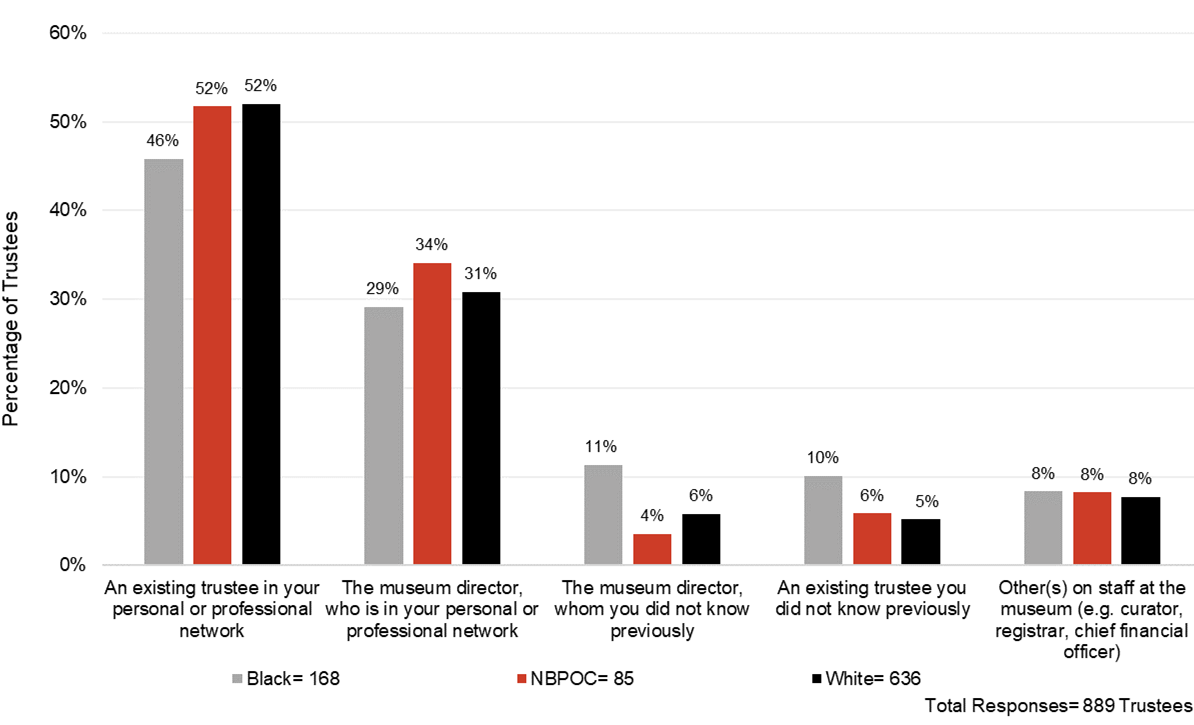

Networks

Black trustees were nominated in a very similar way to the overall survey population. Most trustees, regardless of race, either had a preexisting personal relationship with the museum director, or with an existing trustee. As Figure 6 shows, 29 percent of respondents had a personal relationship with the director and 46 percent had an existing relationship with a trustee. This strategy heavily relies on pre-existing networks rather than larger environmental exploration or pipeline programs. While network approaches may limit representative diversity on the board, they can be an effective strategy for diversification if trustee networks are diverse. Therefore, museum leadership may find that the diversity of a trustee’s network is an important strategic consideration when recruiting for nomination to the board.

Figure 6: New Trustee Prospecting by Race

The majority of interviewees said that they joined the board through a personal or professional connection. In some cases, at the start of their trusteeships, they were partnered with an existing board member to assist them in informally learning about the board.

Interviews revealed that it is typically the case that the museum approaches the trustee candidate to initiate the conversation and extend an invitation. One interviewee relayed that in addition to joining through an existing relationship with the museum director, they also pushed for their own trusteeship. After volunteering on an advisory council for a DEAI committee at their museum, they wondered why, considering the work they had done, they were not being considered for the board. While initially pushing for the role themselves, the museum’s chief diversity officer ultimately advocated on their behalf. When asked about the onboarding process, this trustee responded that, “I think the assumption is that people who are on the board have been on other boards. And this is my first board as well. And so the chief diversity officer, again, was indispensable and gave me insight into the political stakes. I never would have been able to do it without her.”

This trustee’s experience illustrates the lack of an onboarding structure in some museums due to the expectation that a trustee has previously served on other boards. This lack of structure could lead to feelings of alienation for a new trustee, who may not fully understand all the complexities of their board nor board service more broadly. This trustee was able to rely on their director and the chief diversity officer as major supporters in their success and overall acceptance as a board member.

Artist Board Members

Evidence gathered in this project indicates that trustees are often recruited based on their professional experiences, which allow board members to make important contributions to the museum based on their expertise. Artists, for instance, have valuable insights that prove helpful to board conversations about exhibitions, collections, and programming. One artist-trustee we interviewed shared an example of a useful intervention she made, saying: “I was questioning why this particular artist was having another show, when they had a major show there 10 years prior.” This board member was able to recognize that it might be damaging to the museum and the artist to repeat a major solo show in the same institution. Furthermore, “There was an opportunity for them to look at other artists who haven’t had that platform for them to bring in.” In this case, the trustee’s perspective was valued, likely because of her knowledge of the optics of the proposed exhibit for artists and the broader public. However, this trustee shared that it was not always possible to make such interventions: “I voiced my opinion in that situation, but there were other times when I didn’t feel like I could. I think there were so many people that were used to leading the conversations, you felt like that’s just how the conversation was going to go.” While artists may be seen as valuable assets on the board when questions arise that are specific to their domain of expertise, they may also face challenges when confronting long-established leadership hierarchies in which artists and their board contributions are less valued. Artist-trustees also express having to be mindful of how their critiques and suggestions might be interpreted by museum directors and fellow trustees who can wield significant influence over their artistic careers.

Committees

Trustee work is typically organized into committees. These committees include a subset of the board members, and each committee works on a specific topical area. Committees then make recommendations, which often result in a vote from the full board. Table 2 reflects the committees most commonly found on museum boards, with explanations of the activities for each.

Table 2 – Committee Descriptions

| Committee | Purpose |

| Building/Property/Grounds | Concerns use of museum facilities and grounds, assessments, renovations/improvements, new building projects and expansions |

| Collections/ Acquisitions | Engages in accessioning and deaccessioning strategies |

| Community Engagement/Education/Outreach | Develops strategy for engaging new communities and providing educational opportunities for the public |

| Director Search Committee | Works to recruit new executive director to the museum during periods of leadership change and transition |

| Diversity, Equity, Inclusion | Develops DEAI strategy including communications and statements, and institutional investments in DEAI training |

| Executive | Subcommittee with varying levels of executive privilege to act on behalf of the whole board, dependent on bylaws |

| Finance | Reviews institutional finances and audits |

| Fundraising/ Development | Develops strategy for donor recruitment, fundraising events |

| Governance and/or Nominating | Recruitment and nomination of new trustees; governance of the Board |

| Investment | Monitors and oversees investment of the endowment |

| Task Force(s) or Special Committee(s) | Ad hoc committees for specific issues that arise in the museum |

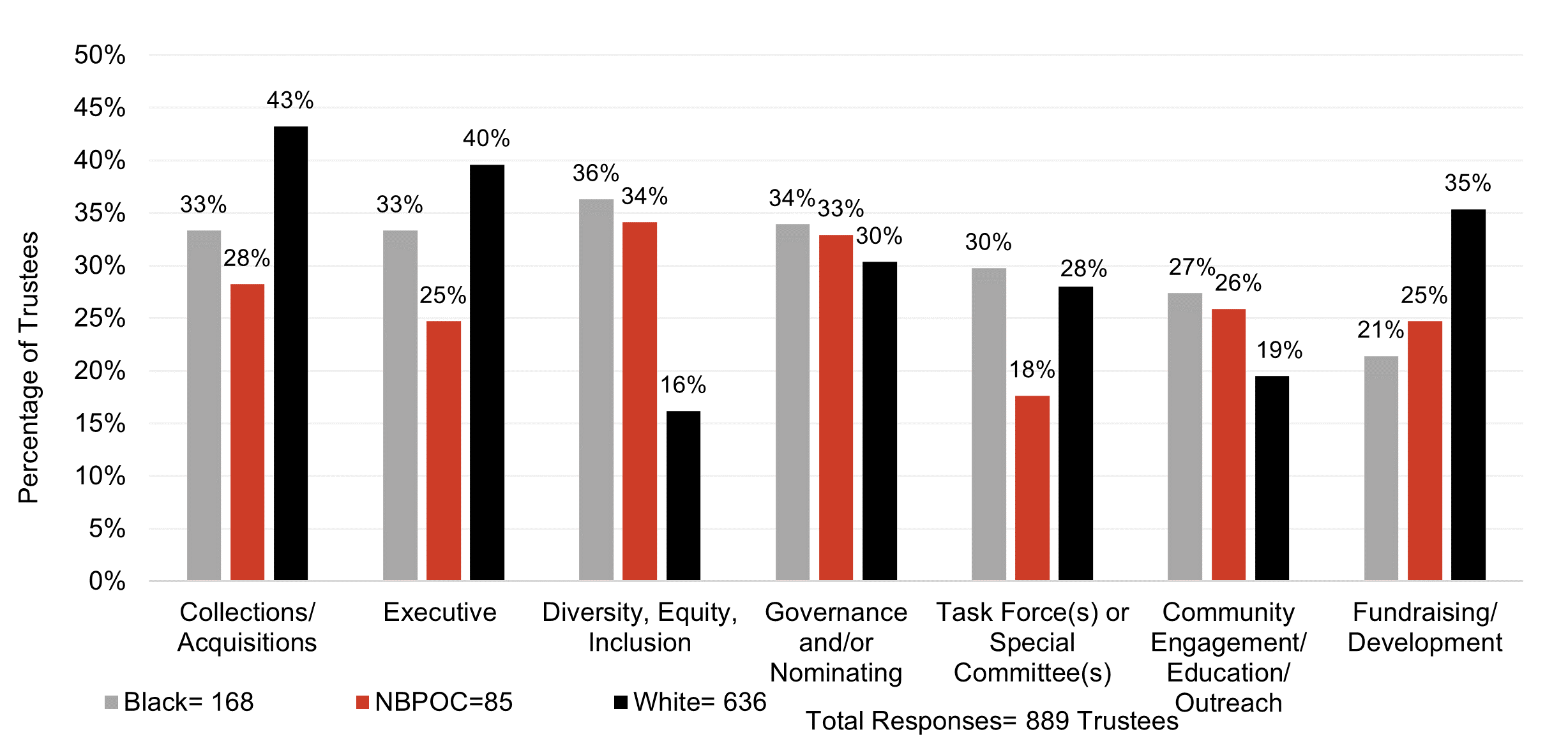

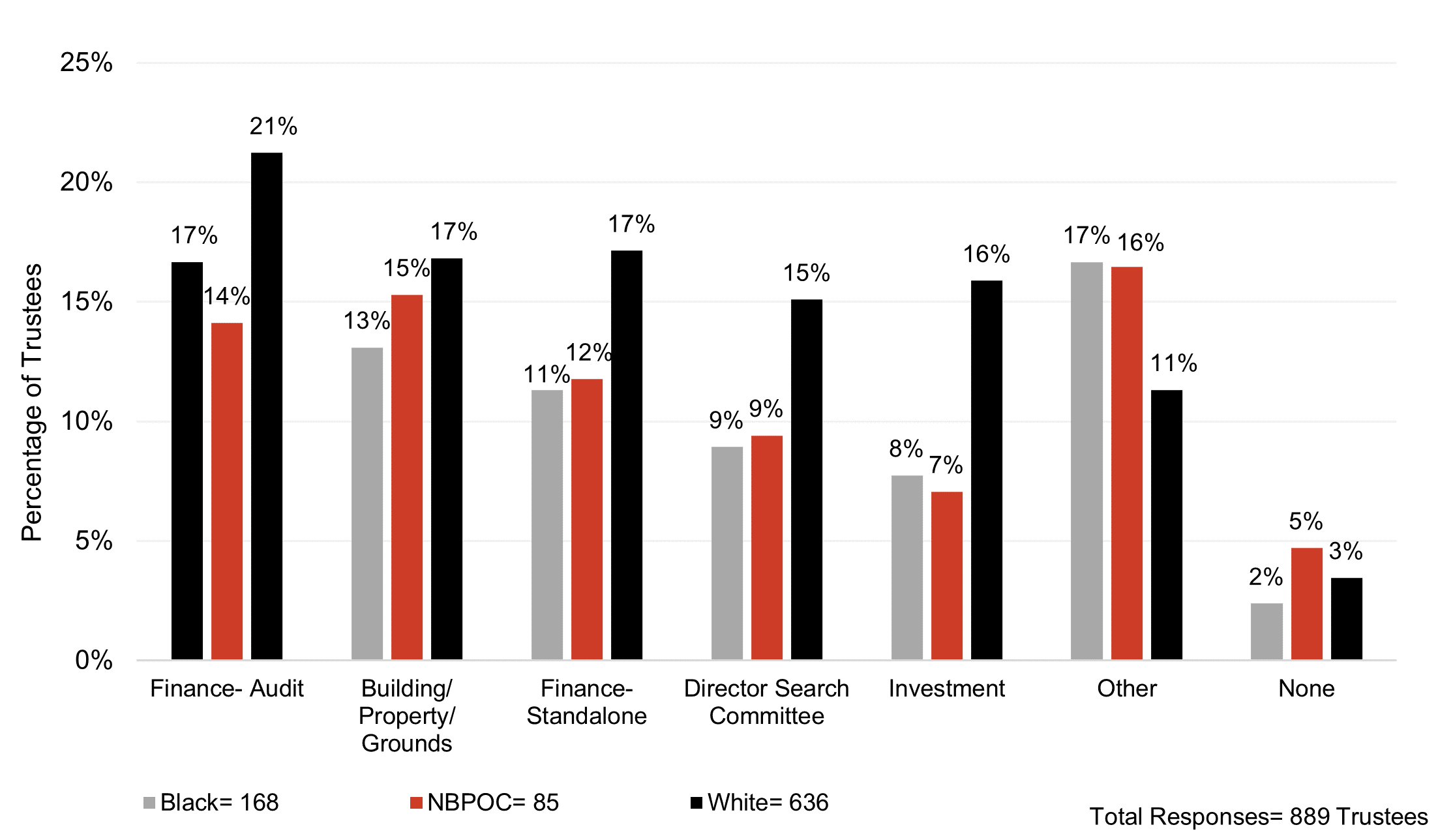

Trustees often serve on multiple committees simultaneously. Over 3,000 committee assignments were reported in the survey, revealing that, on average, respondents participated in three or more committees. Committees can be a productive framework for focusing trustees’ efforts and organizing them around shared interests and expertise. However, when mismanaged, committees can also be ineffective, siloing important issues, reducing the quantity and quality of consequential conversations across the entire board, and creating a false sense of progress.

Certain committees tend to convey more power or status than others. This can vary by institution, but often the executive committee, the investment committee, and the collections/acquisitions committees are thought to wield the most power in the boardroom.

Having a voice in who gets to join the board and who does not is an important aspect of the governance committee. Interview data convey that conversations around nominating can be blunt, highlighting biases among fellow board members that were previously hidden. Interviewees acknowledged that serving on the governance committee can be a key way to change the board’s culture. At a Northeastern museum, one trustee recalled a conversation with their museum director, “I’m sure you’re thinking I’m going to be on community engagement, or education, but I also want to be where the power is. And the power is really in collections, the power is in governance, and the power is in finance, I said. I do not have a finance background, so I’m not going to demand that I’m there right away. But that is the trajectory. And now I have a very strong voice on the governance committee, leading many of the charges there, which gives you the power to actually reshape the board, and really set practices, and really help move the culture along.” As this trustee realized, it is important to advocate for representation across specific committees based both on an individual’s expertise and interests, as well as having a say in the essential operations of the museum.

Among survey respondents, collections/acquisitions, executive, fundraising, and governance are the most frequently held committee posts (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Committee Membership by Race (1 of 2)

Figure 7: Committee Membership by Race (2 of 2)

One of the most important committees for the museum’s mission is the collections and acquisitions committee. This committee has an important role in determining what works enter the museum’s collection and what works leave through deaccessioning, which allows for an increase in the acquisitions budget. The survey found that Black and NBPOC trustees are less likely to be on the collections/acquisitions committee than their White colleagues.

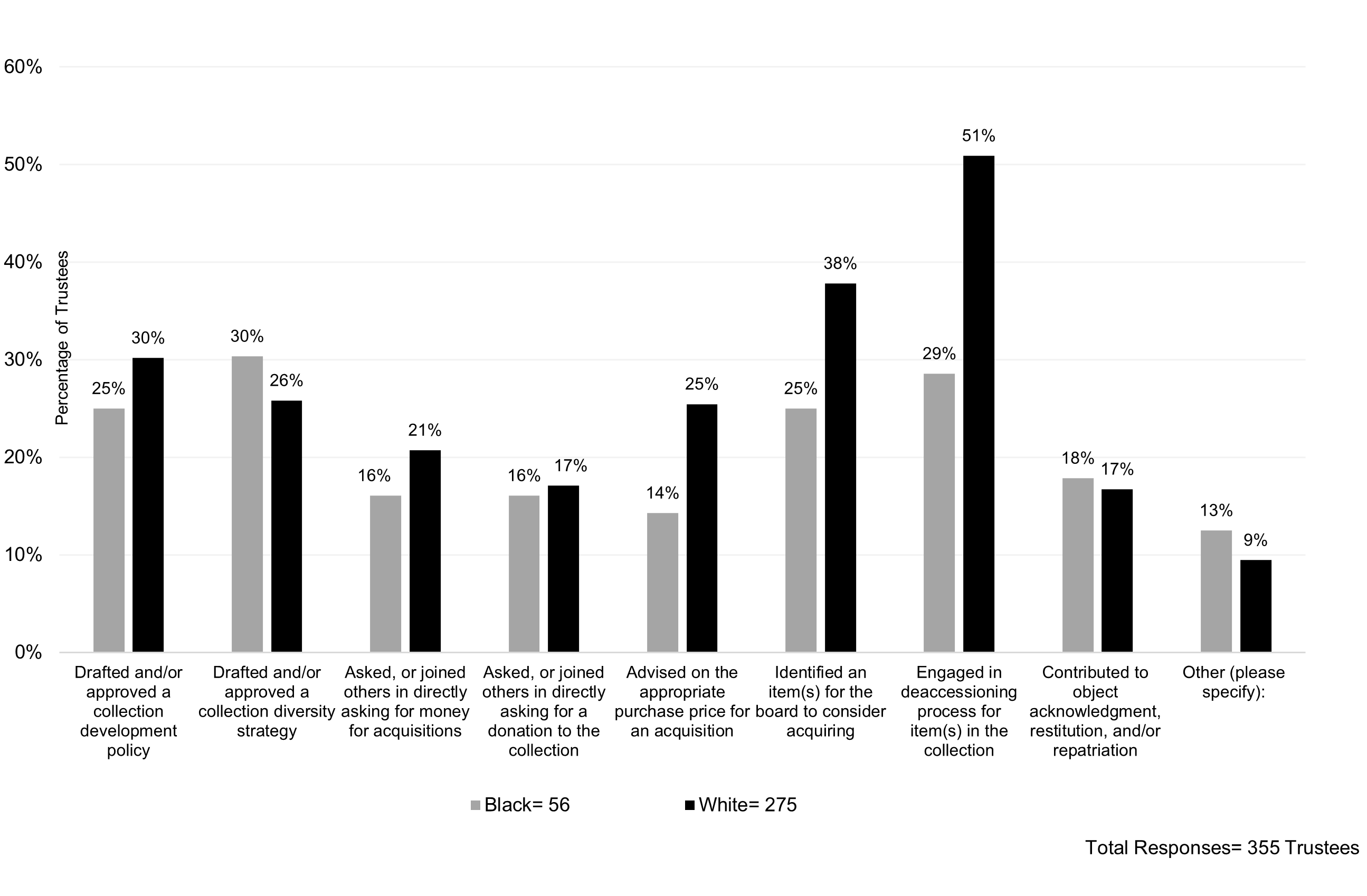

If respondents reported that they were part of the collections/acquisitions committee, they were asked a follow-up question about the different kinds of activities they engaged in on that committee. Black trustees are far less likely to engage with the deaccessioning process than their White counterparts (Figure 8). They are more likely to draft and approve collection diversity strategies. These findings reflect a tendency for Black trustees to be siloed into diversity-oriented roles and less frequently engaged in the core operational work of the museum. However, 26 percent of White collections committee members work on diversity committees too. This suggests that while the tendency for Black trustees to hold diversity oriented committee positions is clear, but it is nevertheless a marginal difference.

Figure 8: Collections/Acquisitions Committee Activities by Race

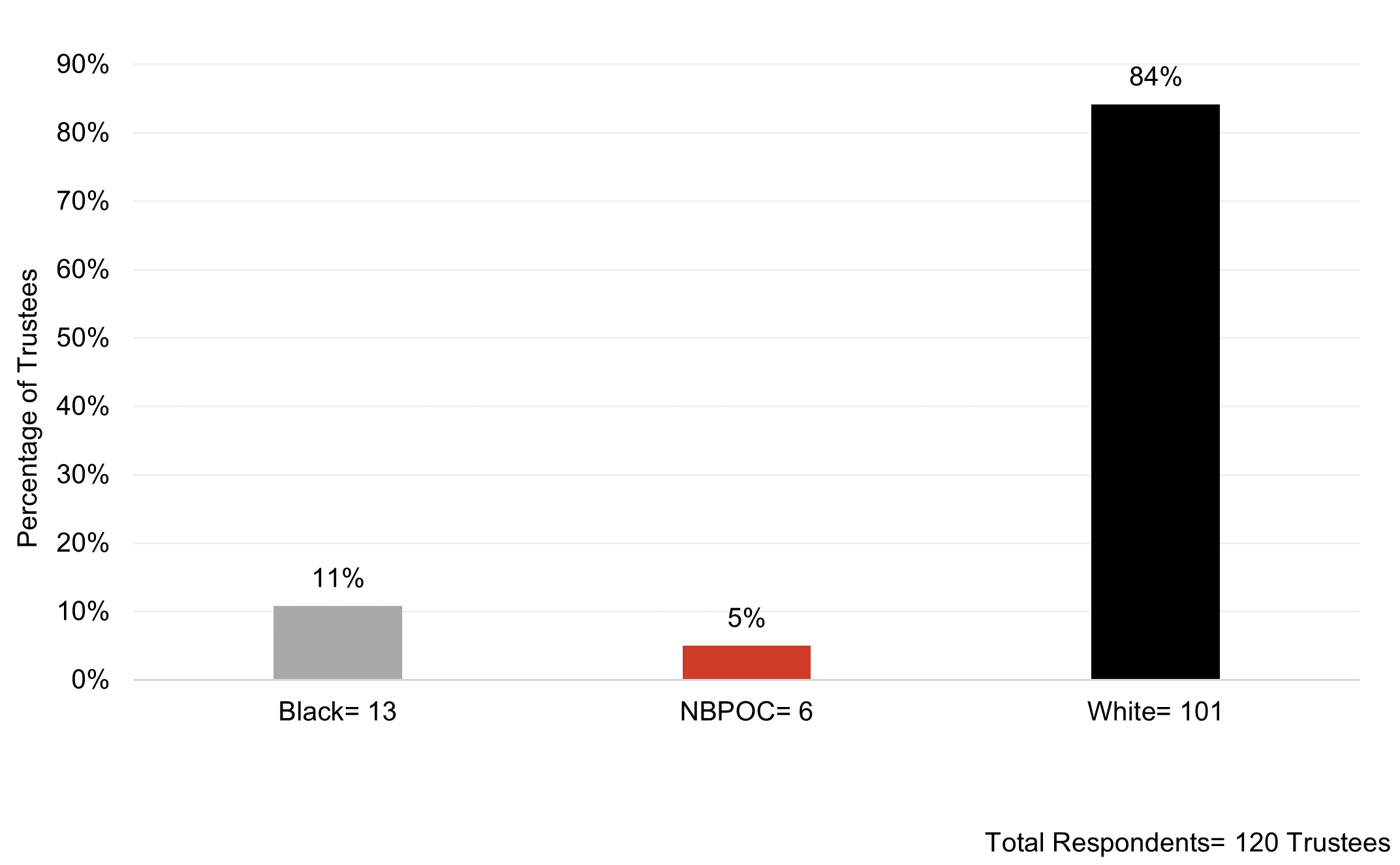

White trustees were twice as represented on investment committees than Black trustees. The investment committee plays an important role in the financial health of the institution, often hiring a third party to actively invest endowment funds. The committee can also ensure that a museum’s DEAI strategy extends to identifying high-performance investment managers of diverse backgrounds for the museum to engage. It is more likely for Black female trustees to serve on the investment committee than Black male trustees, and it is also more common for White male trustees to serve on the investment committee than White female trustees.

Figure 9: Investment Committee Members by Race

During interviews, some trustees highlighted working with diverse money managers, a meaningful product of impact investing within art museums. Impact investing is defined as, “investments made into companies, organizations, and funds with the intention to generate social or environmental impact alongside a financial return.”[7] In response to the racial reckoning in 2020, many museums released statements pledging solidarity commitments. For many institutions this included making steps towards impact investing and adjusting their investment policies to reflect their mission statements. In reference to BTA’s research in partnership with Upstart Co-Lab, “approximately 35% of their respondents reported that a portion of their endowment portfolios are currently managed by BIPOC and/or women fund managers.”[8]

Experiences and Perspectives

This survey gathered characteristics of trustees and details about their nomination process, committee assignments, and roles. In addition, trustees reported their perspectives and attitudes about their experiences on art museum boards. When considering the experiences of Black trustees, the survey instrument focused on gathering details about trustees’ motivations for joining the board, and, in certain cases, why they are considering leaving their board. It asks about their degree of satisfaction with their board experience and the degree to which they feel their expertise is valued on the board. Examining these responses provides a snapshot of how the North American population of Black trustees are responding to current dynamics among their fellow trustees.

Why did they join?

Black trustees wrote that they chose to join their boards because of a) valued personal relationships, b) the need to diversify the board, and c) their ability to create points of access to new communities for the museum. Some respondents reported that the strength of the existing museum program also clearly played a major role in their decisions to join. This confirms findings from previous studies; trustees are more likely to support a museum if they see an existing program that reflects their values.[9] One trustee reported that the museum’s collection expansion strategy aligned with her public advocacy work. Another trustee pointed out the need for Black people to have a seat at the table in institutions that have historically excluded them: “The museum has a long history of not being inclusive or welcoming to the Black community. While there was very little representation of Black community members when I joined, I felt strongly that one cannot affect change if you have no seat at the table. I really see it as a responsibility to the community to be a voice for those who have none.”

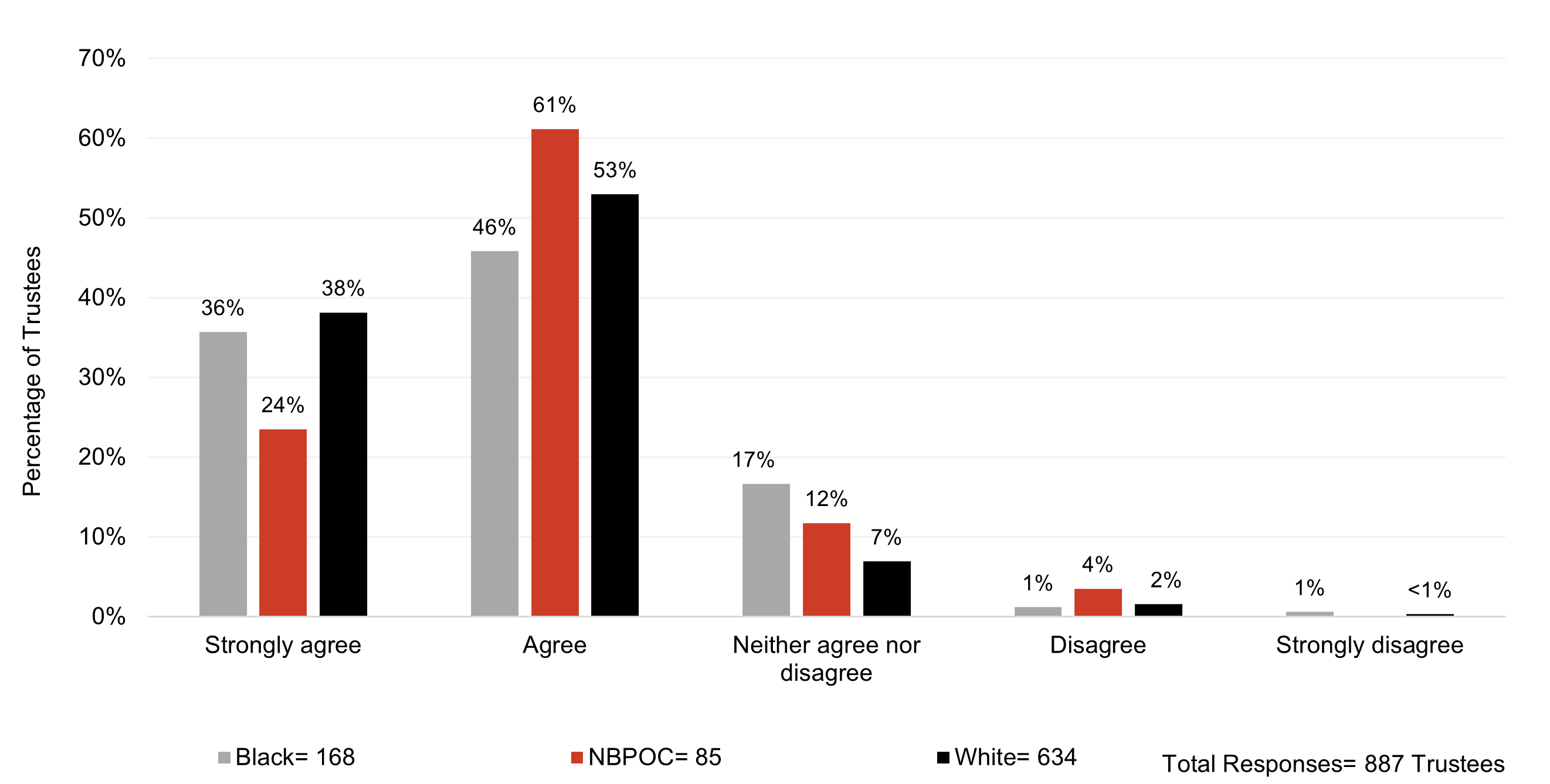

Aggregate Experience

Survey respondents reported their level of satisfaction with their board experience on a five point scale. Board members primarily responded positively about their experiences in the aggregate. Across the entire survey population, 87 percent agreed or strongly agreed that they were satisfied with their experience. Among Black trustees, the figure was similar: 82 percent of Black trustees agree or strongly agree that they are satisfied with their experience. Responses are organized by race in Figure 10.

Figure 10: Degree of Satisfaction with Board Experience by Race

There was no meaningful difference by gender; Black men and women both agree or strongly agree they are satisfied with their experience.

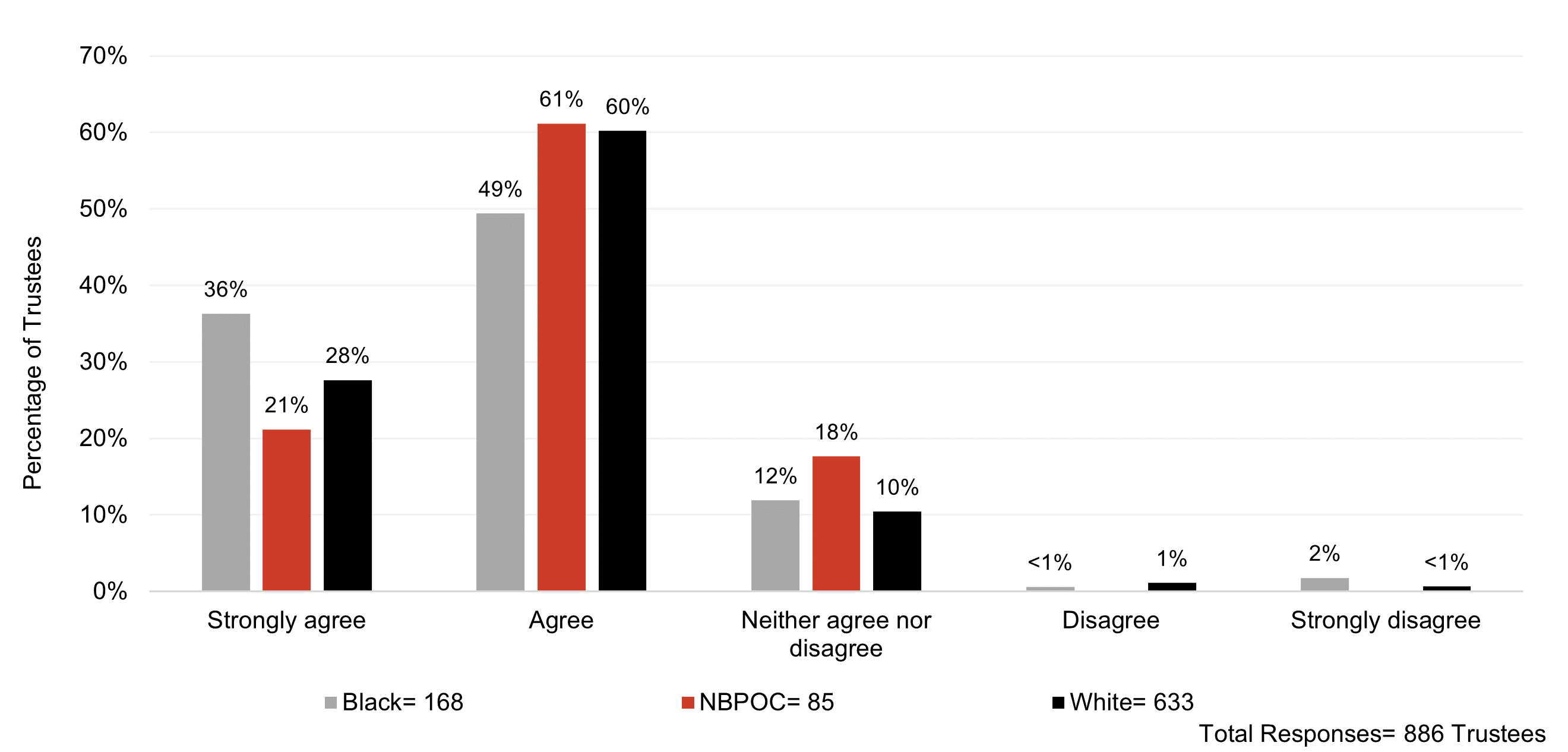

Likewise, when asked whether trustees believe their expertise and perspectives are valued in board discussions, a clear majority agreed or strongly agreed that they were. This, too, was similar across racial groups (Figure 11). Black women reported “strongly agree” at the highest frequency of any subgroup, at 37 percent (White women: 26 percent and NBPOC women: 28 percent). This data point may be a reflection of the high frequency of Black women trustees holding PhDs or professional degrees.

Figure 11: Degree that Expertise and Perspectives are Valued by Race

Trustees were also asked whether they were considering leaving, and if so why. One trustee explained that she was a friend of a trustee and had a desire for a specific education program to come to fruition. She was disappointed when it did not and felt the pace of change was too slow. Another trustee echoed this perspective: “I’ve felt frustrated by the pace of change. I know change takes time (and we’ve made some meaningful changes), but I’ve also felt us stagnate before getting to the big stuff. Board recruitment / retention is an example of this: we haven’t been willing to look at ourselves as a board and what we can do better.” When asked how the board might improve, this trustee said: “I wish that board members were willing to put their own desires aside for the good of the museum. I wish egos were smaller.”

Another respondent shared that they were disappointed with their board experience, namely due to issues of class: “I am on the nominating committee and had some unpleasant experiences where it was clear to me that board service was really relegated to the upper echelon of society and that is distasteful for me as someone both from a financially disadvantaged background and as someone who has worked professionally on behalf of those living with poverty.”

Art museum boards are known as sites of cultural cohesion for elite social groups.[10] Trustees who seek to disrupt class boundaries on the board are likely to face deeply entrenched barriers. These conflicts may intersect with racial identity and can lead to attrition from trustees who are resistant to the entrenched values of their fellow trustees.

Sentiment

In addition to questions about their experience, respondents were asked to use three words to describe the culture of their board. Table 3 shows the words used most frequently. The first column shows the top five words Black trustees use to describe their board culture. The second column shows the top five words for all other trustees.

Table 3: Word Frequencies

| Black Trustees | White and NBPOC Trustees |

| Committed | Committed |

| Evolving | Diverse |

| Engaged | Engaged |

| Friendly | Inclusive |

| Passionate | Supportive |

The high frequency of the word “Evolving” to describe the board room among Black trustees is noteworthy.

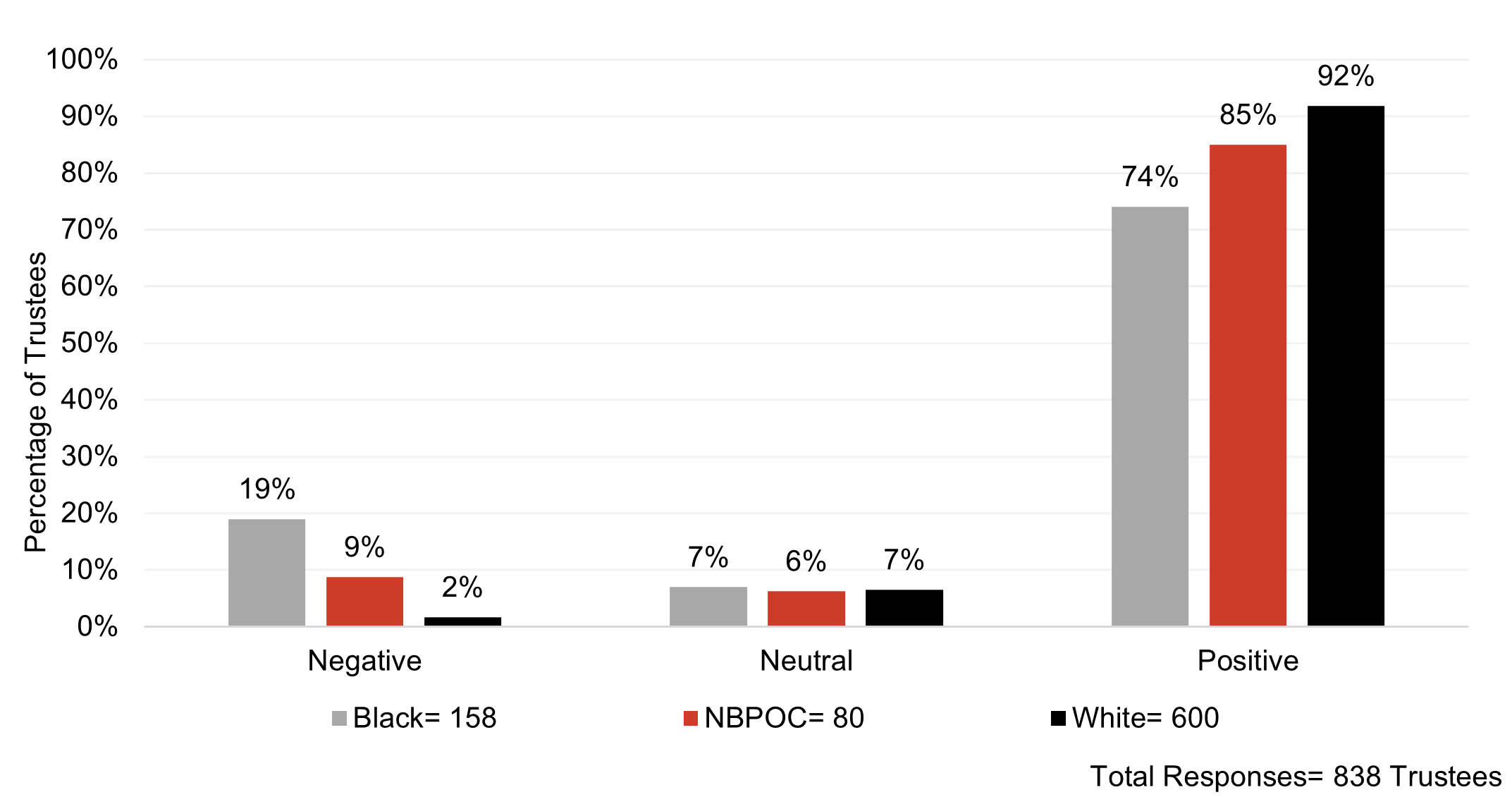

By coding these words, these data were then aggregated into a sentiment analysis, as can be seen in Figure 12. While the majority of word use is clearly positive, we also see that Black trustees used negative words with a higher frequency than their fellow trustees.

Figure 12: Sentiment Analysis by Race

Socialization and Engagement

Our interviews illuminate the socialization processes through which Black trustees come to learn about their roles and responsibilities, as well as the structure and culture of art museum boards. Respondents report their experiences of both informal and formal onboarding processes. For example, one trustee characterizes her onboarding as “not real formal.” The trustee was on-boarded by their mentor, allowing them to ask about the requirements and expectations tied to board service. Additionally, they had the opportunity to informally connect with the museum director and curators to learn more about the museum’s structure and culture. Despite the informal approach to onboarding that they experienced, they also understood the value of formal onboarding for new board members: “I’m in the process of onboarding somebody else, and I’m like, ‘Do all of these things.’”

Contrasting the above experiences, another respondent recalls a formal onboarding process that aided in their socialization into the world of art museum board service. The trustee described participating in a formal orientation where they had an opportunity to meet several trustees, as well as the major gifts officer, and learned about the various board committees. The gifts officer was instrumental to their onboarding process: “So, he really essentially took me by the hand, talked about the various committees, put me in contact with the chairs of those committees, and walked through and arranged for me to take behind-the-scenes reviews of the committees. That was kind of part of the formal process. He explained the scheduled meetings where the trustees would discuss various issues and would then vote.” The onboarding experience also served as an invitation for the trustee to share their perspectives: “The gifts officer explained, ‘We want to hear your voice, your voice is important to us. Everyone is encouraged to speak up.’” Since their onboarding, the trustee has informally built connections with other board members: “It’s been really great to just have those connections, and people are very open and welcoming, and talking to you to see what your interests are, letting you know what’s going on. So, it’s only been a little over two years, so I’m still getting to know everyone.”

As detailed in the above excerpts, trustee socialization happens through formal and informal channels in which Black trustees come to learn about the inner workings of art museums and the roles and expectations of serving on the board. Importantly, formal and informal onboarding opportunities are seen as critical for building relationships among trustees. For example, another respondent observed that there have not been adequate opportunities to connect with board members outside of their formal meetings, recommending that their director should “create more opportunities for board members to engage with each other outside of the board and committee meetings.” This comment supports the idea that museum directors should be actively managing the climate and culture of the board in order to facilitate alignment and strengthen relationships.

Diversity, Equity, Access, and Inclusion

Several Black trustees reported that their board lacked inclusivity and diversity or needed to take active steps towards addressing complex issues like repatriation. One trustee highlighted the importance of repatriation standards and suggested that Black Trustees should lead in this effort: “Black trustees should develop a series of standards that we feel are appropriate for determining whether a piece should be returned or repatriated. You know, these considerations are moral, ethical, and legal. So for me, is there a moral responsibility to return artifacts? Absolutely. Is there an ethical obligation to return artifacts? Absolutely.” Throughout the interview, this trustee expressed discomfort with the lack of support from museum leadership on this issue.

Another respondent shared feeling a disconnect based on the difference in lived experience between herself and other board members. When asked if she is considering leaving the board, she said, “I considered leaving the board because I don’t feel like I belong. The majority of trustees are White people who don’t work for a living. I am a BIPOC woman who works full time for a living, and I often feel disconnected from the reality of other trustees. I also considered leaving the board because it is a lot of additional work and commitments for me, and I am burning out.” As another respondent described: “The board is not as inclusive as I had hoped, not sure the best way to weigh in on issues without ‘rocking’ the very embedded norms.” This comment reflects the flip side of the “evolving” board; often the process of evolving can produce friction in the short term. These quotes reflect feelings of disengagement and alienation, which indicates that there may be uncomfortable or even toxic dynamics on some art museum boards.

Interviews with Black trustees highlight the significance of diversity, equity, access, and inclusion (DEAI) work at their respective museums. Importantly, trustees contrast a holistic and proactive approach to DEAI work with what can be characterized as a “reactive” or “crisis” approach.

One trustee described the holistic approach to DEAI work that their museum championed years before they joined the board. According to the trustee, the board created a DEAI subcommittee through intentional efforts rather than “through a crisis.” The subcommittee has allowed the museum to “do really deep work, and not just kind of the superficial work of buying up a bunch of people of colors’ work and putting it on display.” In fact, this particular museum has undergone a holistic collections assessment, including using metrics to track their priorities. The trustee recognizes that the museum and board are “not without their own struggles,” including for example, the small proportion of people of color on the board. However, their overall assessment points to the importance and value of the board’s decision to take a comprehensive approach to DEAI work.

Another respondent points to a “reactive” approach to DEAI work being done at many museums. For example, it is their perception that institutions “are maybe doing DEAI work because they feel like they have to do it rather than actually because they want to do it.” What this means is that the changes they make are less substantive. The respondent notes that DEAI work is not only about the representation of people of color; DEAI is also relevant to policies around labor and staffing. Additionally, DEAI work marks “a larger cultural shift” for museums and boards that speaks to an organization’s values and priorities.

The above excerpts illustrate the importance of taking a holistic and proactive approach toward making museums more diverse, equitable, and inclusive. This approach involves thinking about the structural dimensions of museums, such as labor and staffing matters, in addition to the inclusion of diverse collections.

Tied to the holistic approach to DEAI mentioned above, other respondents speak to the ways in which their museums are actively building their DEAI infrastructure. One respondent shared that their museum was engaged in various conversations with consultants to strengthen their commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion, including unconscious bias training for the board and creating a Diversity Committee. Over the years, that museum went on to hire a chief of community learning and education, under whom the diversity, equity, and inclusion work lived. That person then hired a director of equity and belonging, who has now been in place for about nearly two years. The respondent shared that the chief of community learning and education reports directly to the museum director, signaling the museum’s commitment to bolstering their DEAI efforts. The museum’s DEAI infrastructure also includes a staff working group: “So, there’s kind of a parallel motion with the board and the staff. And I’ve been advocating for a helix kind of model where we’re working independently, but then coming together to make sure that there’s alignment.” Despite this progress, the respondent acknowledges that DEAI efforts can feel “really slow to move,” but also understands that “it takes time” to make substantive changes.

The above excerpt describes what is true for many of the Black trustees who we interviewed: concerted efforts are being made to infuse diversity, equity, access, and inclusion into the fabric of art museums, albeit in ways that can often feel “really slow to move.”

Three Trustee Perspectives

This report has shared a quantitative analysis of survey findings, contextualized with relevant evidence gathered from interviews with Black Trustees. In this section, we share the perspectives of three trustees who provide lessons for the field. These trustee perspectives resulted from interviews and are edited for clarity and length. They include:

- Dana King – Artist and Trustee, Oakland Museum of California

- Alicia Wilson – Trustee, The Walters Art Museum

- Darrianne Christian – Chair, Newfields Board of Trustees

We thank these institutions for granting permission to include these perspectives in order to provide valuable insights for peer museums.

We highlight these three trustee perspectives to illustrate different ways trustees can proactively address issues of diversity, equity, access, and inclusion among their board, staff, and visitors. These trustee perspectives are not highlighted for the purposes of elevating or endorsing individual institutions as exemplary, or more advanced than others in their approach to DEAI issues. Rather, they were selected because of the value these trustees’ experiences can offer to readers.

Trustee Perspective: Dana King

“I am very proud of the work that we’re doing at the Oakland Museum of California. People have a sense of belonging, and we work very hard to build that from the inside out.”

-Dana King (Artist and Trustee, Oakland Museum of California)

Dana King’s perspective on the board and museum operations at the Oakland Museum of California (OMCA) reveals several lessons for the sector. King describes a climate in the boardroom that has been generated by both bottom up and top down accountability, particularly for anti-racism and DEAI work. She notes that raising minimum salaries is crucial for cultivating an equitable workplace. OMCA has made substantial sacrifices in order to ensure that everyone working at the museum was earning a fair, livable wage. At the same time, they have changed the development culture in order to make events more accessible to a broader set of constituents, rather than only those willing to pay for a table at a gala. And they have loosened guidelines around giving requirements for board members in order to generate a more inclusive environment that relies on contributions of time and expertise, as well as monetary contributions. Below, King offers her account of experiences on the OMCA board in her own words.

I was recruited to the Board of Trustees by the Executive Director. I love being here. It’s a very welcoming place. And different from any museum I’ve ever been to.

We received a $3 million grant from the Irvine foundation in 2012 to really explore and address how we treat the visitors to the museum and to understand who lives in the immediate vicinity of the museum; because the zip codes in the immediate vicinity of the Oakland Museum are the most diverse economically and ethnically. Many people from those zip codes were not showing up at the museum. We wanted to encourage that interest and find out why it wasn’t happening. What could we do to encourage them? Our research department has a scoring system, and we ask our visitors through surveys, open ended questions, and closed ended questions, “How does it feel to be here?”

Our DEAI work has trickled down, and it’s trickled up, but I would suggest that the trickle up has been more significant. During COVID, we started to work on becoming an anti-racist institution. And it was driven by staff. And so when we shut down, we had the opportunity to really do that work and to see it in action. By action, I mean that we have significantly reduced the hierarchy. Transparency in the institution is a priority. From financials to building maintenance, to security to everything in between, all of it is available to suggestions from anyone. Feedback on exhibits or programming that we’re working on, it’s available to anybody. So now we have this truly cross functional, working institution; nobody is in silos anymore. Staff members do their daily work, but if something of interest comes up that they want to participate in, they have all access and every way to participate. We also have meetings between staff and the board. We ask them questions, and they ask us questions. It’s a constructive dialogue around the table rather than a hierarchy.

We also changed our pay structure so that there is no salary lower than four times the national poverty rate, which translates to approximately $26 per hour or more than $51,000 per year. In doing that, we knew that our budget would only go so far. And that, ultimately, we would have to entertain downsizing. And we worked with staff, and the staff supported this knowing full well that there would be a restructuring. But in doing so, we knew that it would raise the level of income for everybody at the institution. And then we gave those who were part of the downsizing the first opportunity to apply to any job that came up within the institution after we made that shift.

We have a mission statement and a set of priorities that runs through the entire institution, all the way through to our vendors. We want our vendors to have the same values that we are building within the institution. And we are now reworking our finances and our philanthropy to match our vision and values. We will no longer have those big, bold, beautiful functions where everybody comes in ball gowns, and the tickets are $1,000, to start. We want to find a way to invite the entire community to participate in fundraising for the institution. Because what we found is that if people are not asked, they’re not fully included. And therefore they don’t feel a part of the growth of the institution. And we want people to feel comfortable, whether it’s a $5 bill they are donating, or it’s $500,000 or $5 million. Understand that it’s all important, and that it all matters to us. And so we’re no longer going to build an exclusive hierarchy of fundraising, which I’m really proud of.

With respect to board giving, we don’t demand a minimum. From each individual on the board we ask that they give to the museum, to the degree that they give anywhere else and to be willing to make the museum a priority. And that’s it. And then that way, our search for new trustees isn’t a financial one, it’s not about money. And that way we really experience the breadth of what people can bring to the table. For our board culture, we have a list of community agreements around how we engage with each other. And we have a check-in around the table, but it’s about something personal, to connect people together. “What book are you reading? How are you feeling as we navigate COVID?” Points of connection, letting the pretenses that we carry fall away. I thought we were a pretty close board, but things like that have made us tighter.

People worry about introducing some of these new strategies and norms. Will the board members who have been large donors stay? We have found that new doors open. For example, we had a Black Panthers exhibition a few years ago that marked their 50 years. Oakland is integral to the history of the Panthers. One of our major donors said that they were not comfortable with us, “advocating on behalf of the Panthers.” Well in fact, we were just telling the truth of history. Big difference. And the person said that if we were to continue down this path, that they were pulling their funding from the institution, not just for the exhibit. The executive director spoke to us about it, and we decided to let him go. Because we knew that that exhibition would open so many doors for us financially and create such access for us out in the community. And so we don’t let money drive our decisions around how we can include, diversify, and expand. And then when COVID hit, we had planted so many of those seeds, that we received so much love financially from our donor base and from our foundations, much of it money we didn’t even ask for; and I think it’s because of the investments we made in building community. To open ourselves up and make the museum accessible to everyone.

The board on which I sit excels at decolonizing the institution, and I’m impressed by the way it builds community and relies on community. People speak their truth, from the boardroom to the galleries, and that’s not welcome in many spaces. But it is welcomed at our museum, and I have been so grateful to be part of the experience.

Trustee Perspective: Alicia Wilson

“I think we’re on a path.”

– Alicia Wilson (Vice President of the board, The Walters Art Museum)

Alicia Wilson, trustee of The Walters Art Museum, discusses the board’s focus on diversifying vendors, particularly with respect to investing the museum’s funds. She also speaks about the work the museum is doing towards increasing the diversity of its collection, which has primarily focused on European art.

The three words I would use to describe our board culture are inclusive, progressive, and innovative. I’m one of the vice presidents among the board leadership. It’s a board leadership team that is racially and gender diverse. Almost half of us are under the age of 55. Contributors to the board who have the means to write the biggest checks do not dominate the officer ranks of the board leadership. I think prior board leadership intentionally made space and room for young and diverse leadership. Our board values the unique contributions that members bring to the organization beyond dollars and cents. There truly is a shared understanding that art museums, if they are going to grow, and if they are going to be sustainable, have to be relevant to a network of people that ordinarily would not have received the first invitation to come behind the museum walls. And so, we, at the Walters, understand that if the Walters or any cultural institution is going to experience growth and maintain relevance, we have to diversify the network of those who are its ambassadors and champions.

On our board, we’ve also thought and acted with respect to deciding who is managing our endowment and how we might engage and incorporate a more diverse group of money managers in its management. I seem to recall that we were one of the first art museums in the country to intentionally diversify the money managers overseeing our portfolio. The board and the whole organization have felt that DEAI has to be embedded in all of our work, and that we all have to be held accountable for measurable outcomes. We don’t have an investment or any other discussion at the board level without talking about DEAI. We ask, “Who are our money managers and how much money is under their management?” “And are we pushing as far as we can?” And the beauty is that those sorts of questions are not asked by a small fraction of the board, but the entire body.

There is measurable progress that we have been able to make in the area of racial diversity and inclusion on the board, and I think the conversation on race has been at the forefront. Just take for example, the makeup of the board. It is one of the few boards where I see eight Black men in leadership. Typically, there may be one or two on a board, but I just don’t get to see that number of Black men elevated to pivotal and critical positions on the board. Our racially diverse board members are leading committees and pushing forth an agenda of growth for the organization. And with respect to women, we are also very forward in the number of women who are leading committees and at the forefront of growth of the organization. That being said, we are still on a journey, but we certainly are being more intentional and digging deeper.

In terms of our collection, it is still very European. We are working on addressing that and some of our latest acquisitions incorporate pieces from all over the world. When we think about diversifying our visitors, we’ve been making really strong efforts to buy pieces that are more reflective of a larger group. I do a lot to introduce people into our museum that previously would not visit. I often host Black women and my young mentees at the museum for a variety of exhibitions. I think I’m pretty effective in making the museum relevant to people. For instance, we had a jewelry exhibit that gave me an opportunity to host women interested in the art of jewelry. So, I feel like that’s my real sweet spot, bringing people to the museum and exciting them about the beautiful artwork that makes up the Walters collection.

The museum board impresses me by the way it responds to the changing times, and that they are open to making those shifts. I think there’s still more work to do, including continuing to be thoughtful about what is being added to the collection, and whether it represents all the values that we all hold dear. But I think we’re on a path.

Trustee Perspective: Darrianne Christian

“I was very clear about the fact that we’re going to be 100% transparent. I think that makes all the difference, because then it shows that you’re being authentic when you can be 100% transparent about everything.”

-Darrianne Christian (Chair, Newfields Board of Trustees)

In Darrianne Christian’s interview, she shared her perspective on the challenges of bringing in a curator of color into a high profile role in the museum. Christian feared Indianapolis was not ready for this curator’s point of view, even as the institution needed to advance their thinking about DEAI issues with respect to their collection and program. She discusses leading the institution through a crisis, as well as adapting to the learning curve of becoming board chair. Christian also discusses pivoting the museum’s programs toward increasing earned revenue in order to move away from spending endowment funds.

I joined the Newfields board in 2016. At the time, I joined because they were looking to diversify the board. They were struggling to do that for a number of reasons, some of which are a result of what we know about systemic racism. First, our market of Indianapolis is not considered to be a top-tier arts market compared to larger cities. Second, there was a minimum giving requirement of $10,000 for board members, every year, over a three year term. Here in the Midwest, that’s a heavy lift.

Third, in my experience, and this may be anecdotal, and it may be true, may not be true. From my experience with other minorities that have the means to give–typically, we want to give to causes that will directly support our communities, not necessarily to something like a museum per se. We see that there’s great need in our communities because of the inequities. We really don’t translate that same need to the arts in quite the same way as we do to causes more closely tied to socioeconomic and racial justice issues. As a result of those lower numbers, that’s how I ended up on the board with no art experience, not necessarily an art lover either. But I’ve always been a lover of museums, and that’s how I started on the board of Newfields.

It was definitely a challenge to be involved at first. Right after I joined the board, I had a baby. I have four children, so I wanted to be focused with respect to my board involvement. Give me something to do, and I’ll do it. But Newfields was what some might call, “a country club board,” for lack of a better term. It was known as the playground for the “who’s who” of Indianapolis. I didn’t necessarily associate with that circle, and I did not regularly socialize with any of the people that were on the board, aside from my friend, another Black woman, who recruited me to the board. Shortly after she recruited me, she moved from Indianapolis, and I ended up being the only minority on the board. I was the only minority for a year or two, I think.

I’m also on another board called the Central Indiana Community Foundation. And one of the things that we identified was that sometimes it’s hard to get underrepresented groups on these boards because of those financial commitments, those minimum giving requirements. We had a program where we paid the fees for underrepresented groups to be on boards around the city, because we saw the value in having that presence. Eventually, there was another young lady, a Black woman, who came on the Newfields board through that route. She eventually rolled off the Newfields board after a few years because, once again, the country club culture meant that the board met in the middle of the day. Well, she was a working professional, and her husband was a working professional. As a result, there were challenges for her that made it hard to participate. And while her feedback, ideas, and commitment were there, it was just very difficult for her to serve, even with someone removing that cost barrier. A lot of times as minority professionals, we aren’t in a position where we 100 percent own our schedule, whether we work for companies, hospitals, or for clients. So there is still that barrier associated with participation. As a result, you can see how the board was not conducive to being very diverse, socially, economically, or, just from a standpoint of different life experiences.

Fast forward, and I find that I actually enjoy serving on the board. We hired a young African American curator who I immediately took a liking to. I really connected with her when she was hired. I was just so excited about her. I had come to hear her speak. And I remember sitting there thinking, “Okay, well, I’m gonna go, listen to about half of her talk, and then I’m going to leave.” And then I remember when she started speaking, I was so enamored with her that I didn’t want to leave her talk early, and I was texting on my phone trying to find somebody to pick up my kids! I wanted to hear everything that she had to say. And I remember thinking, “Oh my goodness, I don’t think Indiana is ready for her!” I mean, honestly, that was my take.

I really tried to do what I could to nurture her; I hosted a coming out party for her when she did her first show, tried to help raise dollars for her show, things like that. And then there was something that happened at the museum where her experience clearly was not working for her. I think a big part of it was just the way things are here in Indiana with the culture and the politics. So she left the museum, and she left very vocally expressing her discontentment. As a board member, and as a friend of hers, I know the types of things that she may have been experiencing. And so I think she really struggled here, and I didn’t learn about everything until after the fact.

It’s difficult because with her being an employee and leaving in that way, it would mean as a trustee, you can’t then communicate with the person anymore because of the sensitive nature of things. I felt like I lost a friend. Then we had another very public incident at Newfields around a job posting that spiraled us right into the spotlight and had my phone buzzing with calls from the community.

I understand my fiduciary duty and to act in the best interest of the organization. I’m on the phone with the board chair. And of course, she wants to talk to me, because I’m the only African American board member. Then the board is on the phone, working through this for hours, just moments after I return from vacation. We put together a committee to manage everything, and I’m asked to chair the committee. And then from there, the board chair and board pretty much 100 percent empowered me and that committee to put together what we needed to do to address this situation. There was never a single ounce of pushback for anything, which I think spoke highly of the Newfields board and their complete trust. They were also completely humbled by what had happened to recognize that we have clearly hurt our community and hurt people. And that was not our intention. I was a junior board member, I had never chaired a committee on the board, although I had been on the executive committee because they wanted my voice. The director would call me throughout my time on the board; he wanted to know what I thought about things and was instrumental in recruiting the Black curator that I talked about. In the midst of this crisis, the director departed, and I was asked to be board chair.

We put together a plan for the institution. What is Newfields going to do and what does that look like? We’ve executed on that plan. We’ve stuck to it. If we said we were going to do something, we did it. And the board was willing to do whatever it took to do it, without hesitation.

We already had the DEAI consultants because we brought those consultants in after we lost the curator who left very publicly. We had already done some basic training with the board with the Racial Equity Institute.

When I took over as board chair, it was a huge learning curve for me, because I hadn’t been a committee chair. I’ve relied on our previous board chair for help with understanding how to do a lot of things. Initially, we needed to diversify our board. Our chair was very honest about the fact that we need to be nimble. If you make this board too big, we can’t be as nimble. So, for our board, we’ve eliminated the $10,000 minimum. We’ve done away with that. We have our annual meeting in May. I actually chaired our governance committee this year; and there were just some things that we needed to address, how we function as a board, and things that I felt could be improved. At the end of the day, you can never get away from people on the board giving; there’s just certain foundations that are not going to give you grants if you don’t have 100 percent participation. I feel that the foundations need to challenge that, too, because it’s like they’re forcing these organizations to do certain things. So, we decided to look at our requirement that everyone on the board has to make a financial commitment. What we’ve determined is that we need board members to give us time, talent, and treasure, but they may not be able to give in equal measure. So, that’s our philosophy going forward. We don’t put that level of emphasis on the treasure part. Time and talent are equally important. At the same time, an organization like Newfields, an art museum, and a lot of these other organizations–when you’re a non-profit, treasure is key to your survival. What we decided is that everyone will be aware of what the board gift is. Those who can give more than $10,000 will, and then there are others who will give less. So, we have what’s considered an overall board gift.

The one thing that Newfields had already started and that was part of our strategic plan is that we are working toward becoming less reliant on our endowment and philanthropic dollars. We lean more towards relying on earned revenue. This year is the first year that we didn’t have to draw on our endowment. Whereas five to seven years ago, right before I joined them, they had a date when they were going to close the doors, because we were spending down our endowment to the tune of 8 percent. We had all of this land with an art museum. If you know anything about art museums, the cost to maintain it is extremely expensive. We had to be creative and figure out ways to bring in additional revenue. Because we have all this additional acreage, we started activating it. Hence why we changed from the Indianapolis Museum of Art–which is what the organization was when I became a board member–and we became Newfields, which is made up of the Indianapolis Museum of Art, the garden, and Fairbanks Park. At Newfields, we have the gardens, where we have these additional events like Winter Lights and Fall Harvest that we’ve activated as additional events at the museum to bring in additional revenue. So, this year, we didn’t have to draw on our endowment.

The other thing we did was to take out our whole fourth floor. We received a grant from the Lilly Endowment; they funded our fourth floor renovation into the LUME, which was previously dedicated to contemporary art. The LUME is an immersive digital experience where you will see original artworks by world-famous artists. We’ve now combined our contemporary art into other areas in the museum. We hosted the Van Gogh exhibit in the LUME, which exceeded our expectations in a way that we could have never imagined.[11] The byproduct of that is that when people came to see the Van Gogh exhibit, they actually engaged more with the museum. For example, when I would come to the museum as a board member, the demographic would fit typical art museum demographics. When you go now, the exhibit has opened the door to more people because there are some people who may not necessarily be able to connect with art in the traditional sense of how an art museum is presented. But, something like the LUME with the Van Gogh exhibit resonates with people. So, we’ve seen a marked uptick in our membership attendees and repeat visitations because people now come to Winter Lights, Fall Harvest, the LUME, and Spring Blooms. They’re coming to more of our events.

What is interesting about Newfields is that during the midst of the pandemic and the 2020 racial controversy, we had the most visitors we’ve had in the history of the museum. We’ve broken every attendance record we’ve ever had. I think a lot of that has to do with the fact that the world and the community saw that we made a mistake and how hard we worked to address it.

As part of our plan, we put together a position description for a diversity officer at the executive level that our new CEO can hire. We wanted the CEO to be able to hire their own person for that position because the chief diversity officer will report directly to the CEO. Prior to identifying our new CEO, we hired a chief people officer, who is also a diversity expert. What we found, I mean, everyone knows this, but there are so many corporations in America that have had DEAI people, but they’ve had no power. Unless you put them directly under the CEO, where they’re reporting to the CEO, and unless we as the board, work with that person as we establish the goals and mission and the vision for the organization, it isn’t going anywhere.

We also put together a scorecard that is a metric for every area on performance and evaluation. Whether it be strategic, people, financial, etc. It should always be something that we measure throughout the organization. The focus on measurement is really important.

And the other byproduct of that is that, as a trustee you’re there to govern. You’re not there to tell the CEO and the leadership team how to manage the organization. The board is responsible for one employee of the institution, the CEO.

One of the things I felt we didn’t do well in previous years was we didn’t listen. Therefore, when our big crisis happened, I just met with whoever would take my call, and there were people who would not take my call. They were like, “Oh, no, Newfields.” But that didn’t happen often, maybe in part because of who I am and who my husband is in our community, everybody pretty much took my call. And board members heard me say that there were people in the community who just felt like Newfields was not a welcoming place. That was very crushing. You know, because they’re board members and in their role, they’re trying to, they want to make this place great, where people see it as a place to come hang out to do all of this stuff. And then the thought process that in spite of all of this, people are saying, I don’t feel comfortable. Or, you know, it’s not a welcoming place for people that look like me, that really resonated. I think that more than anything, it truly resonated.

I was very clear about the fact that we’re going to be 100 percent transparent. I think that makes all the difference, because then it shows that you’re being authentic when you can be 100 percent transparent about everything. Now, of course, as a board, there’s certain things you can’t say, and you can’t do because of your fiduciary duty. But one of the things that I established from the very beginning was that we’re going to be 100 percent transparent, and we are going to listen, and that has not failed us.

When you’re in crisis, you have to hire all these people, like lawyers and communications experts. They were directing me to do things, and I’m like, “No, this is what I’m going to do.” And they were losing it. I told them I’d take the fall. I told them my feelings on what I thought was going to happen. I told them, “We’re going to own it. You just have to own it. We have to tell people this is what’s happening, this is what we’re going to do about it, and we’re sorry.” I think that approach–I think a lot of people are so fearful of the backlash. But, you know, I kept saying to them, “Well, it can’t get any worse.” We were already in the Wall Street Journal, so I’m like, “It can’t get any worse. So, what do we have to lose?”

I think people realized we’re authentic, and that has helped with other areas of the museum. When we started our CEO interviews, we were shocked by how many people applied. We had over 211 applicants for one job. I was thinking people weren’t going to want to touch Newfields because of what happened, but people actually see it as quite exciting to be able to come in at this time and continue to be a part of our work.

Ten Evidence-based Strategies for Cultivating DEAI Values in the Boardroom

The above analysis of survey responses and trustee interviews suggests several valuable strategies that directors, board chairs, governance committees and other constituencies can consider to make the boardrooms of their institutions more reflective of DEAI values.

- Recruit board members outside of traditional avenues. This may mean the museum engages artists or community leaders, search firms, and trustee pipeline programs in order to create more balanced and diverse voices on the board. While network based recruitment is likely to persist, stepping outside of those channels can yield essential benefits.