The Effectiveness and Durability of Digital Preservation and Curation Systems

-

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Introduction: Goals and Scope

- Findings

- Business Strategies of Preservation Systems

- Broader Observations and Next Steps

- Initial Recommendations for Specific Audiences

- Next Steps

- Appendix A: Research Methodology and Data Analysis

- Appendix B: Sustainability Studies Bibliography

- Appendix C: Information Provided to Service Providers

- Appendix D: Interview Questions for Service Providers

- Appendix E: Questions for Clients (Users and Non-Users)

- Appendix F: Acknowledgments

- Endnotes

- Executive Summary

- Introduction: Goals and Scope

- Findings

- Business Strategies of Preservation Systems

- Broader Observations and Next Steps

- Initial Recommendations for Specific Audiences

- Next Steps

- Appendix A: Research Methodology and Data Analysis

- Appendix B: Sustainability Studies Bibliography

- Appendix C: Information Provided to Service Providers

- Appendix D: Interview Questions for Service Providers

- Appendix E: Questions for Clients (Users and Non-Users)

- Appendix F: Acknowledgments

- Endnotes

Executive Summary

Our cultural, historic, and scientific heritage is increasingly being produced and shared in digital forms, whether born-digital or reformatted from physical materials. There are fundamentally two different types of approaches being taken to preservation: One is programmatic preservation, a series of cross-institutional efforts to curate and preserve specific content types or collections usually based on the establishment of trusted repositories. Examples of providers in this category that provide programmatic preservation include CLOCKSS, Internet Archive, HathiTrust, and Portico.[1] In addition, there are third-party preservation platforms, which are utilized by individual heritage organizations that undertake their own discrete efforts to provide curation, discovery, and long-term management of their institutional digital content and collections.[2]

In August 2020, with funding from the Institute of Library and Museum Services (IMLS), Ithaka S+R launched an 18-month research project to examine and assess the sustainability of these third-party digital preservation systems. In addition to a broad examination of the landscape, we more closely studied eight systems: APTrust, Archivematica, Arkivum, Islandora, LIBNOVA, MetaArchive, Samvera and Preservica. Specifically, we assessed what works well and the challenges and risk factors these systems face in their ability to continue to successfully serve their mission and the needs of the market. In scoping this project and selecting these organizations, we intentionally included a combination of profit-seeking and not-for-profit initiatives, focusing on third-party preservation platforms rather than programmatic preservation.

Because so many heritage organizations pursue the preservation imperative for their collections with increasingly limited resources, we examine not only the sustainability of the providers but also the decision-making processes of heritage organizations and the challenges they face in working with the providers.

Our key findings include:

- The term “preservation” has become devalued nearly to the point of having lost its meaning. Providers are marketing their offerings as “preservation systems” regardless of actual functionality or storage configurations. Many systems marketed as preservation systems usually address only some aspects of preservation work, such as providing workflow systems (and user interfaces) to streamline the process of moving content into and out of a storage layer.

- Because no digital preservation system is truly turnkey, digital preservation cannot be fully outsourced. Digital preservation is a distributed and iterative activity that requires in-house expertise, adequate staffing, and access to different technologies and systems. While it is possible to outsource key components of the digital preservation process to a system provider, no digital preservation system is truly turnkey. Today, it is neither feasible nor desirable for a heritage organization to outsource responsibility for its digital preservation program.

- Heritage organizations select preservation systems within the context of marketplace competition. Many observers believe that heritage organizations should support not-for-profit solutions based on shared values and other common principles. But this has not always been the principal driver of organizational behavior. Providers compete within a marketplace that recognizes organizational values as one characteristic among many, such as the total cost of implementation and the feasibility of local implementation.

- The not-for-profit preservation platforms are at risk. They tend to have limited capital and have comparatively ponderous governance structures. As a result, many have not been able to innovate quickly enough to keep up with the needs of heritage organizations. Their business and governance models are often ill-suited to the demands of a competitive marketplace, even if growth is not their primary objective. It seems reasonable to forecast additional mergers or buy outs (if not outright failures) among this category of providers.

- The growing reliance on profit-seeking providers carries risks. The profit-seekers tend to pursue a growth strategy, and by this measure they are succeeding. Private capital and a decision to scale across multiple sectors has enabled this category of providers to grow substantially in the heritage sector. Because of a lack of financial transparency, the sustainability of this sector is largely unknowable, and because of a lack of technical transparency, the robustness of the solutions themselves are not widely understood. Competitive pricing and strong service seem likely nevertheless to continue driving growth.

- The diversity of approaches to ensure long-term access to digital content—while a strength—can challenge the imperative to maintain high standards. Given the accelerating rates and increasing complexity of digital information, the heritage community needs a rich array of services. But this array of services must not result in a view that “there are no right ways of doing preservation.” It does a disservice to the preservation imperative if heritage communities are unwilling to critique flawed offerings. Systems designed to play a role in preservation need to strike a balance between agility and inclusivity, taking into consideration the diverse needs of users and organizational resources.

- Very little digital preservation activity is actually taking place. While we did not embark on this project to quantify the level of preservation, there appear to be thousands of heritage organizations undertaking little to no digital preservation activity. While cross-institutional programmatic preservation activities were also out of scope for this project, we note with continuing concern that vast categories of important content types, such as journalism and social media, remain largely outside the scope of any heritage community preservation initiative. Ultimately, heritage organizations are severely underinvesting in digital preservation.

The study aims not only to further increase our understanding of sustainability principles but also to help the sector refine and consider how to best implement them. To this end, we are convening a series of forums to share the findings with members of the relevant digital preservation and curation systems alongside higher education community, funders, and policy makers to facilitate discussions. A series of blog posts, to be published in summer 2022, will incorporate the feedback gathered through the stakeholder convenings and share strategies for moving forward.

We are grateful for the participation of the leaders and clients of the eight digital preservation and curation systems examined in this study. In addition, we greatly benefited from the experiences of several preservation specialists and service providers and appreciate the community’s deep expertise, generosity in sharing insights, and commitment to advancing the field.

Introduction: Goals and Scope

Project Goals and Research Questions

The main goal of the project is to examine and assess how digital preservation and curation systems are developed, deployed, and sustained. Ultimately, through this research we aim to synthesize evidence gathered from a variety of system providers to expand our understanding of their sustainability principles and to engage key stakeholders in reviewing the findings and conceptualizing actionable recommendations. We compare the business approaches of not-for-profit and commercial initiatives, including their long-term strategic planning, governance models, usability studies, market research, risk assessment and mitigation, system renewal, and agility. Such processes are instrumental to ensuring the flexibility to navigate and adapt to change in time of operational challenges, changing priorities, evolving leadership, and shifting funding streams. While we differentiate between not-for-profit and commercial applications, our approach recognizes that in practice this is a false dichotomy as there are hybrid deployment approaches combining tools developed by vendors and not-for-profit entities that operate within the same market (sometimes competing for the same clients).[3]

Our initial review of key initiatives that explore the socio-technical aspects of sustainability has revealed two key issues for further exploration. First, limited attention has been paid to how not-for-profit initiatives develop sufficient capital and agility to thrive in sectors that include for-profit competitors. Second, there has been very little sustained engagement with the funder community to help it consider how altered programmatic guidelines or investment strategies might improve outcomes of both not-for-profit and commercial initiatives. Based on this framework, our key research questions include:

- What business approaches are used to plan and implement digital preservation and curation systems?

- How are the different requirements and resources of heritage institutions factored into the system development process?

- How do initiatives develop sufficient capital and the ability to navigate the landscape to maintain sustainability?

- How could grant funding guidelines or investment strategies improve the outcomes?

Ultimately, the purpose of this study is to offer empirical data to guide the design of future digital preservation and curation systems and the organizations that support them, ensuring that these services and tools remain sustainable and accessible to the users who depend on them. Understanding the digital preservation systems marketplace is especially important in setting realistic and sustainable approaches for the stewardship of new and complex content types and emerging digital formats. This report focuses on the first three research questions. In the next phase of the project, we will address the fourth question.

The target audiences for the study include:

- Leaders of existing digital preservation and curation systems, including project directors, other staff leaders, and governing board members, as well as those who might be interested in creating new systems;

- Organizations responsible for providing capital funding in support of digital preservation and curation systems, including major grant-making organizations as well as emergent groups of libraries and others interested in capitalizing this work;

- Clients of digital preservation and curation systems, including staff in libraries, archives, and museums, with direct responsibility for selecting systems.

The research methodology of the study is described in Appendix A.

Definitions

Digital Preservation

There are a range of risks involved in managing digital content, including technical malfunctions, media obsolescence, and organizational failures—just to name a few.[4] In light of such threats, digital preservation involves the maintenance of digital objects to ensure their authenticity, accuracy, and usability over time. It also requires taking into consideration information security, privacy, and compliance policies. The digital preservation and curation process involves a series of technical, intellectual, and managerial activities. The ultimate goal is to enable discovery, access, and use of content by designated user communities over time. Rather than being seen as a standalone process, digital preservation should be approached as a suite of policies, services, workflows, processes, standards, and expertise required to keep information safe and accessible over time. Such an iterative process entails a network of systems and people and many dependencies. Although our research unit is a “system” (simply put, people, technologies and structures designed to collect, process, store, distribute, and manage information), in practice, the project should be approached through a lens of system thinking due to interrelated and interdependent parts and interoperability requirements involved in the long-term management of content.[5] For instance, how digital content is created/acquired and processed within an organization has implications for preparing content for a preservation repository. An organization’s storage strategies are defined by organizational policies and resources. Disaster planning and risk mitigation requires sufficient organizational resources, especially to bring content to light.

Although digital preservation is a well-established concept, it is highly variable across different institutional settings. Cultural and scientific heritage organizations of all sizes consider enduring access to be a core value and an integral part of their mission. Yet many grapple with setting actionable policies and allocating necessary resources to ensure continued access to digital content.[6] As one interviewee stated, “institutional repositories, curation systems, and digital preservation services are all used interchangeably, sometimes in a confusing way.” Key terms such as “archiving” and “preservation” mean different things to different communities. While storage management, for instance, is a crucial preservation strategy, it does not equate to preservation. Depending on the institutional context, digital preservation may mean retrieving information from legacy media, implementing microservices such as file format transformation, or simply digitizing analog content for retention and online access. The emergence of web archiving and research data management programs has further blurred the boundaries.

Digital Preservation and Curation Systems

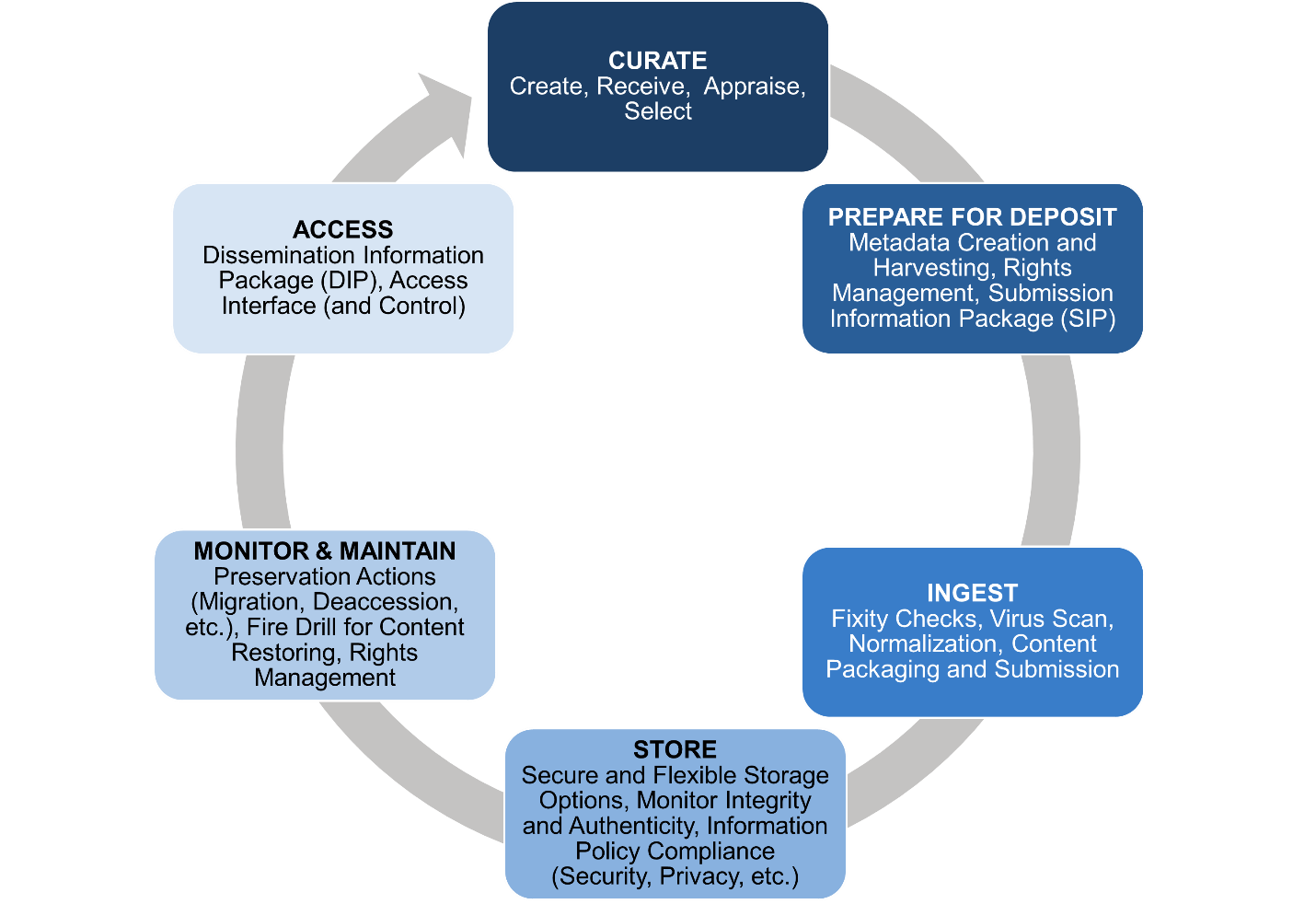

For the purposes of this study, we define digital preservation and curation systems as the tools and services used by heritage organizations to undertake digital preservation and curation work in the context of their institutional needs and priorities. These systems provide a framework for managing the various stages and processes involved in preservation including content acquisition and preparation for archiving, ingesting, storage, maintenance, access, and ongoing data management and preservation activities (see Figure 1: Processes Involved in Digital Preservation).

Figure 1: Key Stages and Processes Involved in Digital Preservation

As we surveyed the digital preservation and curation systems marketplace, it became obvious that there are a range of preservation and curation systems with different technical features, designed for different purposes. Our study focuses primarily on business and operational strategies and is not designed as a technical assessment. Therefore in this study we opted to examine systems and services that cultural heritage organizations might use toward meeting digital preservation goals without trying to put them in different technical categories. Although we focus on systems, also included in our study are the associated organizations and services. Creating a full inventory of digital preservation and curation systems is beyond the purpose of this project. Although it does not represent a comprehensive survey and taxonomy, Figure 2 illustrates the range of systems we considered when selecting which to include in our study.

Figure 2: Digital Preservation and Curation Systems Landscape

Because heritage organizations rely on a range of solutions based on their resources and needs, the initial scope of our study is broad, comprising digital asset management software packages, long-term storage services, and software as a service (SaaS) products used by heritage organizations to undertake digital preservation and curation work.

Sustainability

Simply put, sustainability is the capacity for an organization to continue to operate and successfully serve its mission. For digital preservation and curation systems, sustainability entails long-term maintenance and development as well as the responsible and ethical management of resources to meet the needs of the communities they serve. As we have witnessed the organizational challenges faced by services such as the Digital Preservation Network and Digital Public Library of America, we are reminded of the importance of creating sustainable services with clear visions and value-propositions that are aligned with the marketplace and available resources.[7] Approached as a sociotechnical construct, the sustainability of digital preservation and curation systems entails a number of attributes beyond financial robustness (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Sustainability Attributes of Digital Preservation and Curation Systems

Key Takeaways from Previous Sustainability Studies

Over the past 20 years, there have been several studies on the sustainability of digital preservation systems and initiatives. These studies (see Appendix B for a complete list) include a number of themes that provide a foundation for our investigation:

- A desire for “innovation” in new digital library services during the early 2000s in order to address problems and advance the field (and be eligible for available grant funds supporting innovation) led to the development of many novel tools, often without sufficient emphasis on long-term business planning.[8]

- The development of digital preservation and curation systems is often dependent on soft money generated with limited resources and entails inadequate assessment of the marketplace for future financial stability and growth.[9]

- Not-for-profit systems tend to be led by individuals who are technology savvy but sometimes lack experience or training in developing and maintaining business operations.[10] Collaboration, even among mission-driven open source communities, is difficult to establish and maintain due to competing local priorities, limited resources, and differing branding needs.[11]

- Open source solutions have an especially precarious balance to maintain between community governance and strategic agility.[12] Yet open source solutions compete in the same marketplace with commercial players, where the pace of innovation is relentless.

- To have a competitive edge in the library and scholarly communications sector, stand-alone applications with comparatively static product definitions are increasingly giving way to integrated solutions with fast-moving boundaries and a growing emphasis on data and analytics.[13]

- While a strong commitment to mission is a vital underpinning for any not-for-profit, recognizing the marketplace dynamics, implementing sound and transparent business processes, and being willing to operate within the reality of their constraints are equally essential for long-term success.[14] Business planning should include realistic risk assessments and should happen transparently, rather than being buried in budgeting processes. For instance, it is necessary to expand the community’s understanding of the value of mergers and other organizational strategies that are necessary to maintain an effective and efficient administrative, fiscal, and social infrastructure. Another important challenge is that the not-for-profit entities often do not have the ability to match the marketing resources and experiences of commercial entities.

Findings

Based on the insights gathered from interviews with leaders of eight preservation systems, as well as perspectives from the clients of multiple systems providers, this report is structured under two sections:

The Changing Landscape of Digital Preservation illustrates important shifts in the trends of the digital preservation field, which must be accounted for by heritage organizations and system providers as they consider how they work together. The section provides insights into the common challenges and important considerations that these institutions face when selecting a preservation partner or vendor, including their needs and expectations.

Business Strategies of Preservation Systems highlights the variations and similarities in the service providers’ missions, design principles, and client services. Although there is some inevitable overlap between the two sections, this segment looks at the preservation landscape from the perspective of the system providers.

The Changing Landscape of Digital Preservation

Since the framing of digital preservation as a critical program area for the long-term accessibility of social, economic, and cultural heritage in the early 1990s, a considerable amount of progress has been made toward professionalizing the field.[15] The preservation community is involved in research and continues to refine practices with a deeper understanding of threats to digital content. The digital preservation community, particularly the preservation specialists at heritage institutions and the service providers who work with them, is getting larger, representing deeper expertise around a wide range of digital content types. Within this community, there is a growing appreciation of the need to engage beyond technological challenges with a range of organizational, business, and policy issues. Nevertheless, the testimonies from both service providers and preservation specialists highlight some of the ongoing challenges in this sector.

Local Workflows, Integration, and Interoperability

Interviews revealed that institutions struggle to integrate disparate tools and systems based on their technological frameworks and staffing configurations. Digital preservation is iterative and involves a network of systems and people with interrelated and interdependent parts and interoperability requirements. For instance, how digital content is created/acquired and processed within an organization has implications for preparing content for a preservation repository. One interviewee described an example: “Let’s say a research university decides they need an all-in-one turnkey digital preservation system.[16] They will still pay for and maintain an ILS [Integrated Library System] for collection management, an institutional repository, possibly a separate institutional repository specifically designed to house research data, and Archive-It for web archiving.” The challenge of integrating these separate systems—not to mention paying for them—is daunting for many institutions.

The difficulty associated with trying to align different systems is compounded, if not actually caused, by the organizational structure of most libraries, which usually separates collections from technology and digital asset functions. One critical result is that decision making about digital repository systems and other elements of the preservation, curation, discovery, and access platform environment is often fragmented. Rather than a seamlessly integrated workflow environment for librarians and usage environment for end users, the lack of definition of the interdependencies among separate systems (leading to platform fragmentation) is the unfortunate norm.

Even within the digital preservation and curation systems category, we see fragmentation. Heritage organizations use a wide range of repository systems such as DSpace or Hyrax/Fedora to manage and access digital assets. While these systems offer some content management features (such as creating backups), many do not meet the core digital preservation requirements (see Figure 1: Key Stages and Processes Involved in Digital Preservation).[17] Although several of the preservation systems we explored are designed to interface with repository systems, it is complicated to have them seamlessly work in conjunction.[18] When the principal system only provides a portion of the access and preservation requirements, it is challenging to implement an integrated organizational model.

Preservation Requirements

Our client interviews illustrated that no system is truly turnkey—active preservation requires a network of people, technologies, and policies and needs close collaboration between a client and a system provider. “The big challenge for us was managing gaps in knowledge and skills within the organization,” said one client. “Using this system we realized very early on that it didn’t have all the answers and we needed to upskill staff to be able to use this system.” Another preservation specialist added, “Searching for a turnkey system is a panacea, no system will do the full-life cycle of digital preservation for you,” and commented, “Everyone is trying to hook up several tools and systems together.”

“Searching for a turnkey system is a panacea, no system will do the full-life cycle of digital preservation for you.”

Systems are important in facilitating preservation processes, but they are only a part of the larger picture. As one interviewee explained, at many institutions, 80 percent of the labor that goes into digital preservation “is not technology—it’s policies, workflows [that are necessary] in order to use the systems effectively.” From this perspective, what is needed is a clear understanding of the points of integration among interrelated or disparate systems and an agreement on the need for integration and associated requirements. Cultural and scientific heritage institutions vary significantly in their ability to reserve staff resources and technical expertise for preservation.[19] Preservation is a long-term commitment, so as organizations assess and select preservation systems, they need to factor in what is feasible given the existing priorities, staffing configurations, and institutional policies.

Building Internal Consensus

Given the wide range of processes and individuals involved in curation and preservation, it is inevitable that selecting a digital preservation system may involve significant effort. In academic libraries, for instance, a preservation librarian may develop a strategy for specific content types housed in the collection, but the university’s central IT department may have a competing strategy for the systems that the organization will use. And even very large and well-resourced museums may not have dedicated staff for preservation, instead hiring contractors to solve discrete problems for a specific department, rather than generating an institutional policy or strategy around preservation. This can prove challenging as internal politics determine preservation processes and outcomes within institutions. As one client described: “Our university has been doing some work towards improving our preservation practices, but what’s frustrating here is the territories between departments. I am only enabled to do work with a specific system, and over in special collections they are doing something different. There is a lot of territorial stuff. It is challenging for a preservation librarian to work on their own as they try to develop policy and strategy out of one unit.” Whether they are actual or perceived, such barriers can stymie the progress of system providers attempting to work more effectively with their clients. Strategies for generating buy-in at the leadership level and advocating for coherent preservation strategies across departments are essential towards addressing these issues. Also necessary is exploring the source of variations in practice within an institution to understand if such distinctive practices are necessary or constitute unnecessary redundancies.

Another challenge is reaching a consensus on which collections should be preserved and at what level. This can happen in the absence of a digital preservation policy that explicitly states the scope, purpose, and context of the organization’s digital curation and preservation program. This type of blueprint is needed to set priorities and allocate resources. Many interviewees expressed concerns about the ability to build a cohesive preservation program at the level of an individual institution. As one interviewee articulated, “Sometimes each unit is seeing only one part of the digital preservation cycle often driven with personalities and no one is in charge of a cohesive picture.”

Evaluating Community Solutions in the Marketplace

Although there is strong philosophical support for open scholarly communication systems among the clients we talked with, there are local impediments to embracing this principle in practice. As one interviewee noted,

I am very much on the side of OS, overall organizationally, within the library up to the dean there is an understanding of the benefits of open source and free systems, including open educational resources and open access materials. However there is very much a strong impulse to use commercial systems of large vendors for our services. At scale you can save money. Running/implementing open source can be very prohibitive if you don’t have access to developers and dev/ops. It is hard to retain staff. It is sometimes logical to go with a commercial provider.

This was one of a number of examples we heard where open source and community-provided infrastructure was philosophically preferable but did not compete effectively in the marketplace.

Both clients and system providers highlight how the lack of technical expertise within an institution presents a significant barrier to adoption.[20] Although open source communities involve support groups and mechanisms, they may not be able to match the level of customization and ongoing support offered by vendors. Library leaders are worried about their ability to support open source implementations and are more open to using (and paying for) fee-based vendor solutions. As they make significant investments, some are assessing return-on-investment and accountability. For instance, both library and museum staff described how a memorandum of understanding with a vendor establishes well-defined deliverables and holds the vendor accountable for delivering the desired product to their institution’s specifications. Conversely, agreements with community-based services tend to focus on membership requirements, dues, and other governance-related obligations. As one user described,

We need to get over our reluctance to use vendors. It is easier to advocate when there are prices. When you put numbers in front of decision makers at the library and show long-tail costs it becomes more real. Not-profit-models often hide costs, other than membership costs. It is difficult to know how much you are spending and justify the same level of investment over time.

Some not-for-profit entities have clearly defined service levels and requirements; however, the perception among some of the clients we talked with was that efforts in relationship management sometimes emerge as a more important priority (especially given limited managerial support).

Proliferation of Content Types and Preservation at Scale

Another major shift in the preservation landscape over the last two decades concerns the characteristics of materials that are in need of preservation. In the past, heritage organizations focused their preservation efforts primarily on digitized textual and visual materials. Now, between research data, audio visual materials and born-digital content, such as social media content and web sites, preservation needs are more complex.

In some cases, the growing scale of this content is not being adequately addressed by libraries or system providers. The client interviews indicated that many institutions are still focusing on preserving digitized content (or locally produced content) without being able to adequately strategize for the long-term management of born-digital content and large media files. This is a concern because while digitized copies of material collections can be recovered if lost by re-digitizing, born digital content once lost may be lost forever.

Centralization of IT and Security Policies

Many universities have either centralized their IT units to allow more cohesive governance (including implementing security policies) and fiscal management or are in the process of evaluating the value of distributed IT models. This trend reduces the flexibility of libraries to set priorities and their ability to specialize in library-related technologies and standards. Centralized IT strategies typically focus on shifting the institution towards cloud systems and their commercial-grade security. Many academic clients see this increasing centralization of IT at the institutional level as yet another emerging impediment for deploying systems that require local development resources.

All services need to factor in institutional security and privacy policies. Several digital preservation specialists interviewed brought up institutional security and the privacy policies associated with storage as a growing constraining factor in their selection and implementation of digital preservation and curation systems. As one noted, “It is becoming harder to use open source tools and the university is moving towards enterprise systems especially to fulfill security issues.” Storage selection and management is a critical part of every digital preservation approach. There are limited resources to guide comparison of various storage options including internally hosted digital preservation systems or cloud-based systems. Cloud computing has emerged as an integral part of the technical infrastructure, introducing both efficiencies and new questions. For instance, assertions about the reliability and durability of cloud storage providers have not been fully tested. Another important issue to be explored is the rising costs as the initial “loss leader” pricing has given the impression of unlimited, low-cost storage. Several interviewees mentioned the need for more nuanced research about the nature of cloud arrangements and how they compare to enterprise level or local storage.[21] An ethical or values-based assessment might especially be important for not-for-profit entities.

Business Strategies of Preservation Systems

The preservation systems we studied are highly differentiated in terms of their mission, business model, and structure. One of the criteria used by heritage organizations in accessing different preservation systems is the trust in organizational stability. Given the vendors’ marketing and communication efforts to address the community concerns, the once-widespread mentality that “You cannot rely on a commercial vendor with your heritage materials” is challenged. Our analysis revealed that while certain systems tend to focus on heritage organizations and their specific needs, others aim to expand beyond this sector (for instance, addressing the archival requirements of the life sciences domain) to offer broader functionality and establish greater financial stability.

System Development and Community Building

A system roadmap is a strategic plan that describes goals and desired outcomes and includes major steps or milestones needed to reach it. It serves as a high-level document to articulate strategic thinking, especially as a communication tool for various stakeholders. The ways in which roadmaps are developed and research and development investment decisions are made varied among the systems studied. For instance, not-for-profit and community-based systems’ governance structures allow members to engage directly in determining the direction of products and services. By contrast, commercial vendors pursue a more centralized process for platform development.

The distinction is somewhat nuanced rather than a perfect bifurcation, as commercial providers have expanded their efforts towards user research and community engagement. One of the clients observed that vendors “still function like a private for profit when they set a roadmap and make the decisions on product development, but they do a better job of listening to the community now. Membership meetings involve prioritization of potential features to develop on behalf of attendees.” While vendors do rely on feedback mechanisms to gain insights from users, they filter that evidence through an internally designed product framework, which helps them to control the growth of their platform. At times, this process can be subverted if a client with deep pockets chooses to pay for certain developments that they would like to be prioritized. Commercial vendors often see this as a win for their entire client base, as the newly developed features become available to all.

The commitment to inclusive and democratic decision-making processes from community-based systems aims to foster collective ownership and transparency. The roadmap is generated based on user engagement on common solutions to local problems and often involves consensus building that may slow down the forward planning process to take account future circumstances and requirements. One possible drawback of such a principle is the lack of executive decision making, especially to provide nimble leadership (decision-making power and authority) in setting strategic directions for the service, especially in moving from the needs assessment to implementation stage. Another, as discussed below, is that open source contributions are sometimes made based on the priorities of the contributing library rather than those of the community as a whole.

All system providers acknowledge the importance of community building and realize the role of word-of-mouth and reputation in this tight-knit preservation community. They feel the pressure to better understand the preservation strategies and processes of members/clients, particularly to address the barriers related to in-house preservation processes that are prerequisite to archiving.

Previously, this might have been a source of differentiation for the not-for-profit solutions. But, as one library preservation specialist interviewee shared, “Earlier in my career it seemed as though vendors were very tight lipped about their solutions, which for a profession like digital preservation felt like the wrong position to take. But they do a better job of listening to the community now, membership meetings involve prioritization of potential features to develop on behalf of attendees.”

Bringing clients together in communities of practice is an underlying marketing principle for all the systems in our study. The system providers make an effort to cultivate a strong and vibrant user community with conferences, camps, discussion listservs, peer-to-peer communication, mailing lists, and more. Some vendors mentioned that they provide “digital preservation therapy” as their staff works with libraries and archives that have experienced significant data losses or are dealing with complicated situations. Non-profit systems can benefit from the enthusiasm of the community for contributing labor to build the product, which comes from an alignment with library values. Community-based systems often require active participation, contributing to professional development in preservation among its members.

Challenge of Selling Preservation Services

The commercial service providers indicated that it often takes years for an organization to commit to buying a solution. As one described, “Sometimes we find it challenging, particularly in the GLAM [Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums] sector, to manage long sales cycles.” The system selection process involves both understanding the options available and also trying to make a business case to the senior leadership to secure buy-in: “The heritage organizations have limited budgets, are under ever increasing pressure, and have high expectations of what a digital preservation solution should do for them, especially if they are planning on providing access to the world.” Some commercial system providers shared that they have found it challenging to provide a product at a price their heritage sector clients are willing to pay. “The RFP [request for proposal] process is boom or bust, and it can take a long time,” one vendor noted.

The commercial digital preservation and curation systems we reviewed are more open to broadening their client segments beyond the cultural sector. Conversely, not-for-profit entities may not have the ability to work in multiple markets unless explicitly stated in their missions. One advantage for vendors with multiple market segments is being able to rely on different revenue streams: “If one environment is struggling, other markets might be doing better.” However, expanding preservation systems customized for the needs of different sectors (such as heritage organizations, private companies, and governmental entities) can be a double-edge sword. On one hand, the strategy helps to diversify revenue sources. On the flip side, given the differences between sectors, it might be increasingly challenging for a vendor to meet the expectations of each client type. These tradeoffs inform business strategy as system providers work towards serving the needs and managing the expectations of clients across sectors.

Given the wide range of individuals involved in writing preservation system RFPs and the tall order of requirements, it is inevitable that the selection process can be arduous, taking significant time (especially given that there is no perfect system out there). Commercial vendors mention “over-analysis paralysis and spinning wheels” faced by potential clients and advocate for more efficient assessment processes, such as implementing pilots as institutions try to compare different systems. Several library and museum staff interviewed noted how the challenges involved in implementing a system become apparent after they started working with it. As one system provider described, “One thing we’ve found, it’s a real struggle for archivists to generate buy-in for the projects they want to run.” This interviewee believed that this was a challenging task from a communications perspective: “There’s a lot of technical jargon, use of acronyms, I think if the language could shift slightly and be more accessible that would help people understand the importance, the value of these initiatives. But it quickly gets into technical language. Trying to break down those barriers would gain a lot of value.”

Benefits and Drawbacks of Open Source Systems

Although open source does not equate to heritage community control, and community control does not always establish openness, for several not-for-profit initiatives, open source is often crucial, especially if they are not organized to offer a great deal of user support. They rely on community engagement as a principal mechanism for contributions to the code base. Several of the systems we examined include open source system components, which have drawn clients who are interested in actively participating in the preservation of their institution’s materials.

Enterprising library staff who believe in open source solutions are enthusiastic about contributing their institutional labor to the preservation efforts of their peers in the field. Developing staffing expertise locally to build capacity for navigating the unforeseen future challenges of preservation can be beneficial for the institution. Incentivizing community contributions can mean that the product grows in a distributed—rather than in a centralized—way. When community members develop code in their own institutions, they naturally want that code to be shared back with the broader community. Although such a strategy engages members and encourages them to contribute to the code base, it also presents the risk of uneven code development based on local requirements that may not be as relevant for the broader community.

There is also a tradeoff around incentivizing clients to make contributions to an open source system versus having a defined roadmap. As an interviewee from a heritage organization asked, “What do you do when a member says, ‘Here’s something we’ve done locally, but it’s not on the roadmap. We want to contribute it [to codebase]’?” In such cases the not-for-profit systems may feel pressure to integrate the change because they want to incentivize that kind of engagement. The tradeoff is that those development cycles were devoted to the priority of a single institution, rather than the community-determined roadmap for the service.

“The foundation of the industry is OS, everybody we talked with whether they are using a commercial or community-based product recognize that customers cannot be locked into a solution and preservation systems are work-in-progress and will continue to evolve.”

Beyond not-for-profit initiatives, certain commercial vendors perceive open source as the foundation of the preservation industry and are committed to relying on and embracing such tools in the system architecture. One vendor interviewee noted, “the foundation of the industry is OS, everybody we talked with whether they are using a commercial or community-based product recognize that customers cannot be locked into a solution and preservation systems are work-in-progress and will continue to evolve.”

Exit Strategy

One fear that clients share is that it will be difficult, and potentially even impossible, to move to an alternative digital preservation system or service. A provider’s exit strategy is therefore critical as clients assess systems. Some not-for-profit systems focus on bitstream preservation and therefore guarantee that there are procedures in place to retrieve and move institutional content in case of a service discontinuation (business closure) or if a member institution decides to use another preservation system. The general perception has been that extricating content out of a commercial system—which may not offer the same level of transparency and openness—will be more complicated. However, our interviews indicate that commercial vendors recognize that clients cannot be locked into a solution as the market continues to evolve. All the vendors we interviewed have put in place succession and exit plans to further increase the confidence of potential clients (although we have not investigated if the strategies indeed are effective in practice). While both commercial and community-based solutions have some type of exit plan already in place, this is likely to be an area of growing competitive differentiation.

“If you can’t exit from our preservation system, it is not a preservation system. The question is not whether you can get your content out or not, it is how complex it is to get it out.”

Commercial service providers are cognizant that heritage organizations might refrain from working with them because they are afraid that heritage materials might get locked in. “We train our clients on how to stop using our product, and escrows allow us to migrate content in the case that we don’t exist anymore,” described the CEO of a commercial system. “If you can’t exit from our preservation system, it is not a preservation system. The question is not whether you can get your content out or not, it is how complex it is to get it out.”

One interviewee shared how the transparency of commercial providers has changed over time:

Because the idea with digital preservation is that you should show your work in order to prove that you’re preserving your collections, I always felt as though our commercial system provider was a bit of a black box, when I first encountered it. Over time, as the system has matured and the company culture has changed, they have become more open, more collaborative with the community.

There is a risk of discontinuation for both commercial and community systems, and all the systems included in the study “plan for their own demise” as they are conscious of evolving technologies. One of the vendors expressed, “We believe that an important part of preservation is transparency, and that memory institutions should be able to demonstrate at every stage what happens when they process cultural heritage materials for preservation.” However, implementing an exit strategy is a shared responsibility. Even when a system provider, whether it is not-for-profit or commercial, is able to provide the digital content “back,” having an exit strategy does not mean that there are processes in place to bring content to light with an appropriate access mechanism in the face of loss or failure.

Goals for Growth and Stability

The participating systems had different goals in terms of their growth projections. It was most common to hear that commercial systems were open to growth in multiple sectors, while non-profit providers tended to focus on building services for a more specifically scoped group of institutions.

For-profit service providers are following a growth model and adding new user sectors, such as technology and pharmaceuticals. Responding to emerging needs, they offer features to support compliance and regulatory requirements, particularly for handling personal data such as student records and complex user access policies dictated by different policies. The ability to scale the same core investment across multiple sectors and pursue resulting revenue growth across the sectors without commensurate increase in their cost basis is a significant advantage of some commercial offerings.

Other providers have a very different mindset. Several of the community providers made clear to us that they are not pursuing a growth model and instead are looking to scale to a coherent community with which they are most closely aligned from a mission perspective. This alignment is valuable and perhaps even necessary when the starting point is community governance, as discussed below.

Other than technical failure or losing data, the biggest threat to the stability of any provider is losing clients. The commercial providers we talked with believe their client-base to be quite stable. While assessing this stability was outside the scope of this project, the vendors reported that they have committed user communities that are content with their product. For some of the not-for-profit providers, the picture is different. While clients may be more committed organizationally, for example because of their ongoing open source contributions, they may be less satisfied with the service’s ability to keep up with their changing needs and expectations. To be sure, it may be too simplistic to attribute these differences purely to a commercial/not-for-profit dichotomy or resulting growth goals and access to capital. It is important to note that, compared to commercial entities, not-for-profit organizations tend to be more transparent about their operations and uptake.

Governance Models and Finances

Not-for-profit systems tend to begin from the principle of community governance and control. This brings self-evident benefits yet imposes an inescapable overhead cost associated with the governance model. The commercial systems are privately owned. They default to streamlined forms of governance with an inescapable tradeoff in limited transparency in decision-making and governance.

In recent times, not-for-profit providers have grappled with their models as they continue to experiment with different configurations. Several continue to evolve as they iron out issues such as diversity, equity, and representation to move towards flat models without privileging those who can pay more (and subsequently may have more influence). Bandwidth that is devoted to these values is necessarily carved out of other priorities. As one interviewee put it, “There is a risk of spending too much time on governance issues.”

Leadership and staffing differ as well. The commercial systems included in the study tend to have four-member leadership teams comprising a chief executive officer, chief financial officer, chief operating officer, and chief technology officer. The community-based systems often involve distributed leadership as they count on active participation from member organizations. Commercial systems account for all the costs that are required for product development, client support, and sales, while community systems try to keep their direct costs as low as possible by keeping contributions from community members “off the books.” The non-profit community-based systems have an average of two full time staff members (without factoring in hidden/unseen labor) whereas the commercial ones employ 40 full time staff members.

The service providers are cognizant about the need to control costs and realize the risks involved in increasing service fees. A large portion of the commercial systems’ revenue is recurring, generated by selling annual, subscription-based licensing products. Although there is heavy reliance on revenue generated through membership fees, community-based services seem interested primarily in serving a group of institutions and are careful about expanding the membership as they aim to maintain an engaged community. As described earlier, rather than pursuing an active strategy to grow the partnership, they focus on making sure the current partners remain committed to the community.

Not-for-profit systems acknowledge the need to diversify their revenue streams. However, expanding membership to generate additional revenue can create challenges: as members’ needs diverge and governance becomes more complicated and burdensome In means of diversifying revenues, one of the impediments is understanding the true cost of the operation by tracking and recording the unfunded costs.

The systems we examined do not openly differentiate between operational expenses for keeping the lights on and the costs of adding new features. Some client interviews indicated that underinvestment in research and development programs can cause problems as not-for-profit systems scale their products in response to technological and curatorial changes. The modest service framework of not-for-profit systems is a double-edged sword. On one hand, they are able to control costs and expectations. However, they operate on a frugal budget without being able to put aside sufficient funds to support research and development or major technical infrastructure changes.

All the system providers included in this report want to support a range of needs and acknowledge the requirements and affordances of under-resourced organizations. On the other hand, regardless of the affordability of a given system, the deployment process is dependent on institutional resources and skill sets (especially to process/prepare content for deposit and dissemination). Several systems we examined encourage the concept of sub-accounts so that institutions with resources can allow their affiliates (for example a library working with a small historic society) to take advantage of their subscription/membership under their main account. Some interviewees from the client sector questioned how the needs of community archives, especially those curating heritages of underrepresented communities, were addressed in equitable, diverse, and ethically responsible ways.

Evolving Storage Configurations

Storage is a fundamental component of a digital preservation strategy to ensure that bit streams comprising the digital objects archived remain complete and renderable. Storage includes several safeguard mechanisms, such as error-checking procedures to evaluate the outcome of preservation processes, as well as disaster recovery policies to mitigate the effects of catastrophic events.[22]

Embracing cloud technology is increasingly inevitable as digital preservation and curation systems move toward supporting both enterprise and cloud storage configurations. As we discussed above, it is often the case that the decision to move toward cloud solutions is made centrally at an institution as part of a central IT strategy and is not specific to preservation or the library.

Still, it is understandable that in some cases a memory organization would want to have their content hosted locally. Depositing content in a cloud-based system can often mean that it is being hosted by a third-party commercial provider. These providers may be seen as insufficiently invested in the preservation of important heritage material, or at least to have the capacity to shift those investments in the future. There remains a “bird in the hand” mentality organizations that are more conservative when it comes to their preservation strategy.

But the vast majority of organizations are moving toward cloud-based preservation, and if a system provider is not prepared to do the same, their customer base is inevitably going to dwindle. Failure to account for this technological shift poses a meaningful threat to the sustainability of a preservation system. On the other hand, there might be several financial and technical risks associated with locking into cloud-based storage systems. Given that many institutions have access to cloud services at an institutional level, defining the specific value that community-based distributed preservation services provide is important. Making a clear value proposition from a business perspective and retaining membership will be more and more critical for the sustainability of distributed preservation services.

Dark Archiving versus Ensuring Enduring Access

Digital preservation seeks to address several threats; however, the most elementary and most critical one is the ability to decode digital data and gain access to the information encoded within without loss or damage.[23] Bitstream preservation remains a fundamental requirement for long-term digital preservation by monitoring and refreshing storage media, backing up files, performing checksums to ensure file integrity. Certain service providers provide dark archive services, satisfying core bitstream preservation requirements for heritage organizations. For such institutions, focusing on this aspect of preservation and doing it well is sufficient, especially based on their limited resources and focus on digitized content (with analog counterparts).

For others, providing a dark archive without an access system is addressing only a narrow element of the preservation imperative. One service provider asked, “But what about access? To do that you need to build on a user facing application. Categorizing dark archives as digital preservation and excluding services that provide access is a false dichotomy. In that sense, systems that specialize in doing one thing will become important, and they are only ever a subset of the digital preservation puzzle.”

“But what about access? To do that you need to build on a user facing application. Categorizing dark archives as digital preservation and excluding services that provide access is a false dichotomy. In that sense, systems that specialize in doing one thing will become important, and they are only ever a subset of the digital preservation puzzle.”

Our interviewees expressed some concerns about the ability of heritage organizations to provide access to digital content that is preserved in a dark archive. This essential preservation step is sometimes theorized but not tested, sometimes relying on an exit strategy from the repository. Even if the repository offers a well-defined and reliable exit strategy, providing access often requires multiple systems that must be configured to work together. Also, facilitating access might require several preservation actions (in addition to bitstream preservation), such as format migration, emulation, or software preservation to enable a viewing environment.

In any case, the real challenge is moving from just-in-case bitstream preservation towards considering ongoing curation and access requirements. As one client interviewee put it, “preserving in a dark archive and providing access to an archive are complementary but have competing goals.” This individual felt that it made sense to have different repositories for discovery/access and preservation as it was difficult to identify a system that can adequately address the requirements of each operation.

One challenge is that there are not sufficient forums for discussing the shortcomings of dark archiving. Several interviewees mentioned that although data failures occur, there is no open channel to share their experiences about data failure: “Not everyone wants to explain what they lost and what kind of mistakes they have made.” Having more empirical evidence about both what is working well in dark archiving and the risk factors that lead to loss would be beneficial. Avoiding discussions about failure, loss, and what went wrong are problems pertaining to all preservation systems, not limited to dark archives.

Broader Observations and Next Steps

For this study, we examined the business characteristics of eight systems. Therefore, our findings should be approached as an empirical snapshot of the insights, perceptions, and experiences involving these eight systems rather than broad characterizations of the digital preservation and curation systems marketplace. The study highlighted what is working well and outlined potential challenges. The following section describes some of the areas that require attention.

Preservation Landscape

There is a need for a more nuanced understanding of what the systems advertised as “digital preservation solutions” accomplish and the local resources required to fully leverage them.

Each organization views its role and goals through the lens of digital assets that need to be preserved and what preservation entails (e.g., dark storage vs. active content management). Although some systems are presented as turnkey solutions, in reality, preservation is a distributed and iterative process that involves external and internal systems and workflows. As heritage organizations take different approaches to preservation, some are implementing multiple systems for different purposes based on their experiences and content types. As one of the clients interviewed noted, “Organizations need to have multiple preservation solutions and not just rely on one. The complex nature of preservation ecosystems need that diversity for health.” However, it is difficult for potential clients to compare different systems because each system’s preservation mission, competitive advantage, product distinction, and categories of content preserved are unclear, especially based on the information presented on their websites.

Heritage organizations are falling behind the stewardship role that has been expected of them.

Regardless of their type or size, all heritage organizations are curating digital content and therefore need to develop preservation programs. Although it is beyond the scope of this study, interviewees often described the growing gap between institutions with resources and those with limited expertise and staffing.[24] It is unlikely that there will be an infusion of resources towards the preservation mission. Recent studies indicate that the primacy of research libraries that have historically played an important role in ensuring enduring access is in relative decline.[25] There are growing gaps in stewardship capacity. Although several academic libraries have undertaken extraordinary work to ensure the availability of some of these materials for their communities, it is increasingly difficult to keep pace. As a result, a significant corpus is not being collected by organizations that will commit to their long-term availability and therefore will not be preserved for future use and may become lost or inaccessible. While there are a large number of heritage organizations, our study indicates that only a small percentage are leveraging the systems featured in this report. Also, it is unclear how much effort is being put into preserving the knowledge of underrepresented communities and advancing the efforts of community archives, especially capturing the lived experiences and knowledge of community members.

There is a pressing need to conduct empirical studies to assess the broad impact of distributed collective preservation efforts and how they are collectively addressing the grand challenges.

One of the concerns expressed by preservation specialists was how they were attending to locally owned or digitized content and “have not even started to think about how to archive stuff like research data or social media with a range of rights management and privacy requirements.” As heritage organizations focus on archiving digitized or locally held digital assets, realistic and sustainable approaches for the stewardship of new and complex content types and emerging digital formats is not getting sufficient attention. How about large quantities of born-digital content or large multimedia files or software? Even dark storage (and commercial cloud storage) seems to miss the challenge of preserving a diverse range of digital content at different scales. In cases where heritage organizations do not hold materials such as online newspapers, social media, or radio and television programs, there is little evidence that systems are the bottleneck in preserving them.[26] It is not clear if and how distributed community-based stewardship networks are setting collective preservation priorities and assessing gaps.

The effectiveness and applicability of existing audit and certification processes in assessing reliability of preservation systems and stewarding organizations needs to be evaluated.

Audit and certification methods for digital preservation implementations have been in development for well over a decade with different organizations developing different methodologies in parallel.[27] The assessment metrics and processes that garnered the attention of the preservation community two decades ago have lost their initial appeal. Some community-based solutions question what kind of metrics are right for assessing their systems and collaborations. The assessment process tends to be resource-intensive, often only within the reach of well-resourced organizations. Too many preservation commitments are made without enough organizational commitment behind them, while at the same time too many materials of cultural and scholarly significance remain unprotected by any form of preservation commitments. The sector needs to develop assessment methodologies that can be used by different types of organizations to evaluate the reliability, commitment, and readiness of institutions to assume long-term preservation responsibilities.[28]

Preservation Systems

Influencing and shaping commercial offerings is paramount to serve the best interests of the community.

Some heritage institutions feel a values-driven allegiance to community-based systems, while others are wary of the potential “hidden costs” of implementing and managing systems that may not be as user-friendly or agile as commercial products. One interviewee cautioned against equating system provider motives with business models: not all nonprofit products may be offered with the community’s best interests in mind, while not all for-profit products are shaped solely by the profit motive.[29] Although some heritage institutions tend to prefer investing in community based systems that align with their mission-driven values, they are aware that commercial products offer a cutting edge in innovation and are being shaped by the community’s need and not solely by the profit motive. The interviews revealed that some heritage staff want to “get the work done” without spending too much time making it work so they are comfortable with commercial solutions that effectively support their missions. As one preservation specialist expressed, “Community based systems are equitable but there needs to be power to make it work. It is not all about democracy. We need to get the work done effectively and efficiently regardless of who [community vs. vendor] provides the tools.” It is important for the community-based system participants to “shape the future by working with like-minded individuals.” However, several interviewees (from both the system and user/client side) mentioned that it was challenging to sustain internal efforts in the face of insufficient funds. One interviewee said, “When you use an OS system you try to build a system [to work with that platform] and it takes years to build it up, meanwhile the platform keeps on changing.” Given the complexity of preservation programs at libraries, heritage organizations greatly benefit from a rich array of services and competition in the preservation systems marketplace by supporting both not-for-profit initiatives while trying to influence and shape the commercial offerings to serve their best interests.

Given the complexity of preservation programs at libraries, heritage organizations greatly benefit from a rich array of services and competition in the preservation systems marketplace by supporting both not-for-profit initiatives while trying to influence and shape the commercial offerings to serve their best interests

Coupling not-for-profit (and open source) systems with professional services offered by vendors is emerging as an effective strategy.

Increasingly, heritage organizations are accessing systems such as Islandora through a hosting provider (such as LYRASIS, Discovery Garden, or Born Digital) in order to minimize the internal staff resources required to learn and run the system (some commercial preservation systems might also require significant internal resources). Samvera’s products are open source and free to any would-be user, but the project benefits from a number of commercial firms and individual contractors that are active in the community and offer for-fee services, such as consulting, implementation, hosting, training, and more, to interested institutions. Some of these partnering companies have a formal commitment to contributing to the code base and participate in the community. This model demonstrates the advantages of coupling not-for-profit approaches with commercial vendors that can offer services to support system installation, customization, and maintenance to organizations with limited internal development resources. There is a need for more partnerships between commercial and not-for-profit entities—there is room for both, and the community needs both reliable and innovative development and community-based practices.

Initial Recommendations for Specific Audiences

System Providers

- Provide nuanced descriptions of the system functionality and services offered by clearly identifying the distributed roles of the service provider and the client.

- Consider both the operational and development costs involved in maintaining and developing a system (and how operations costs are accounted for in community organizations) and make profit generation a part of sustainable growth in order to fund ongoing refinement.

- Recognize that no single system can address all preservation needs. Engage in constructive competition with other system providers and seek opportunities for collaboration to support the integration of different products.

- Factor in the complicated decision-making processes and expectations of heritage organizations (often distributed across multiple departments) in your marketing and communicating efforts. Your ability to navigate the organizational structure of your clients/partners is essential to generate alignment and buy-in.

Grantmakers and Member Institutions

- Consider the consequences of collective decision making and promote new governance models that assign clear leadership roles and authority to support more agile development.

- Encourage system providers to be transparent about how they distribute revenues to support the ongoing operation and maintenance of the system (and accounting for true costs) while continuing to invest in its future by experimenting and bringing innovation.[30]

- Fund research to investigate emerging storage technologies and configurations in support of preservation and considerations in decision-making.

- Facilitate realistic risk assessment and mitigation approaches for the stewardship of new, complex, and dynamic content types, especially those with copyright restrictions.

Clients

- View digital preservation as a distributed activity that involves both implementing in-house procedures to archive curated content and making contributions to existing digital content repositories that are proven to be reliable stewards. It is neither feasible nor desirable to outsource a digital preservation program to a system provider as curation requires in-house expertise, adequate staffing, workflows, and the ongoing selection and evaluation of technologies and systems.

- Conduct fire drills and test how to bring content to light—not only dark archiving, especially considering the environmental impact of just-in-case archiving.[31]

- Share stories about data loss experiences and challenges in bringing preserved content to light, and concerns about the implications of just-in-case preservation (including the return on investment and potential environmental implications).[32]

- Consider not only the discovery and access but also the preservation requirements of content when working to diversify collection strategies and initiatives.

Next Steps

The findings and initial recommendations presented in the previous sections are based on insights gained through in-depth explorations of eight digital preservation and curation system providers. They need to be discussed and further fleshed out by incorporating additional perspectives. The study aims not only to further increase our understanding of sustainability principles but also to foster a discussion to help the sector refine and consider how to implement the findings. To this end, we have started to convene a series of virtual forums with the members of the relevant digital preservation and curation systems as well as higher education leaders, funders, and policy makers to facilitate community-based discussions of the research findings, their implications, and potential alternative models. Such deliberations will explore the opportunities for putting recommendations into practice and the challenges they might face. An important element of these forums will be considering the varied capabilities and stewardship responsibilities of heritage organizations as they face increasing competition for dwindling resources while expanding their born-digital collections. Community engagement is essential to ensure that the guidance this project offers will be foremost actionable, rather than merely aspirational. In a series of blog posts, we will share the feedback gathered through the stakeholder convenings to build on the research insights shared in this report.

Appendix A: Research Methodology and Data Analysis

Research Methods

The research methods implemented for the study included:

Environmental Scan: We began the study by reviewing reports, project wikis, and social media about the technical, managerial, and socioeconomic aspects of digital preservation and curation systems with the particular goal of enabling us to develop a practical taxonomy of the functions offered by these systems.

Initial Interviews with Preservation Specialists: During the environmental scan, we conducted interviews with 24 preservation specialists to inform our study, get input on which issues to explore, and seek recommendations for which systems providers to include in our study.

Systems Selection: During the initial phase of our study, we identified 34 potential subjects to include. Rather than creating a comprehensive and consistent inventory and taxonomy, our purpose was to identify some of the commonly used solutions to enable us to select organizations to review. We primarily looked at preservation solutions that are commonly used in the United States and have not taken into consideration the international variations in practice. Working with the project’s advisory board, we selected eight systems with different characteristics to enable a more nuanced understanding of the range of tools available, as well as any significant comparisons that emerge across these types of products.[33]

To select the eight subjects, we used the following criteria:

- Used by heritage organizations to support their own discrete efforts to provide curation, discovery, and the long-term management of their institutional digital content

- Supports a range of file formats (format agnostic) and is not limited to a specific content type (such as books or websites)

- Commonly used or under consideration by heritage organizations of different sizes and various resource levels

- Representative of different models such as commercial, community-based, open source and storage configurations (cloud, local)

Through this process, we narrowed down our list of 34 systems to 11 and then randomly selected eight. All eight service providers we selected through this process accepted our invitation to participate in the study.[34] Appendix C included the information provided to the system providers as we invited them to participate in the study.