Unlocking the Power of Collaboration

How to Develop a Successful Collaborative Network in and around Higher Education

-

Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Defining a Higher Education-Focused Network

- Starting a Network: When and Why?

- Successful Network vs. Network Success

- Key Action Steps to Starting and Developing a Successful Network

- Discussion

- Appendix A. Descriptions of Featured Networks

- Appendix B. Research Process and Author Profiles Research Process

- Author Profiles

- Endnotes

- Acknowledgements

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Defining a Higher Education-Focused Network

- Starting a Network: When and Why?

- Successful Network vs. Network Success

- Key Action Steps to Starting and Developing a Successful Network

- Discussion

- Appendix A. Descriptions of Featured Networks

- Appendix B. Research Process and Author Profiles Research Process

- Author Profiles

- Endnotes

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Lumina Foundation for their generous support of this project.

In addition, we express our sincere thanks to the following individuals for sharing their valuable insights through interviews, convening, and email/phone correspondence:

Chad Ahren, Robert E. Anderson, Tom Vander Ark, Peter Beard, Bridget Burns, Jane C. Conoley, Ryan Craig, Richard Eckman, Zakiya Smith Ellis, Elizabeth Evans, Brian Fitzgerald, Mildred García, Haley Glover, Mary Gould, Stacey VanderHeiden Güney, James L. Hilton, Kristin D. Hulquist, Kemi Jona, Tania LaViolet, Simon Kim, Mary B. Marcy, Keith A. Marshall, Barbara McFadden, Julia Michaels, Chris Miller, Stephanie G. Odera, Dakota Pawlicki, Joshua Pierce, Elizabeth Davidson Pisacreta, Scott Ralls, Deborah Santiago, Jacqueline Smith, Yolanda Watson Spiva, Karen A. Stout, Emily Schwartz, Derrick L. Tillman-Kelly, Paul Vandeventer, Anna Drake Warshaw, Bradley C. Wheeler, and R. Owen Williams.

We are also grateful to the three reviewers for their thorough read of a working draft of the playbook, and offering their expertise and knowledge:

- Adrianna Kezar, Professor of Higher Education at the University of Southern California (USC) and Co-Director of the Pullias Center for Higher Education;

- Barbara McFadden, Former Executive Director of the Big Ten Academic Alliance and Co-Founder of McFadden, Rocklin and Associates;

- Paul Vandeventer, Co-Founder, President, and CEO of Community Partners.

We also thank Martin Kurzweil for serving as a key collaborator on the project and providing thoughtful feedback on multiple iterations of playbook drafts.

Executive Summary

Recognizing that solutions to today’s complex problems go beyond the boundaries of a single organization or institution, some postsecondary education leaders and training providers are turning to a more focused and deeper level of collaboration to drive both individual and broader systemic change with potential for far-reaching social impact. Building on the foundations and lessons from past efforts, these collaborations—which we refer to as higher education-focused networks—have become increasingly important in the 21st Century. Oriented around the cross-cutting problems of improving student success and social mobility, enacting structural and cultural change, and managing overlapping organizational responsibilities, these networks develop and strengthen enduring relationships that iteratively generate new ideas and processes to tackle the most pressing postsecondary problems of our times. This playbook discusses the conceptual grounding for these kinds of networks and offers a set of key action steps on how to start and develop a successful network with rich examples from the field.

When and why might organizational leaders choose to take a network approach to higher education challenges? We discuss three situations in which a network approach may be advisable, or even necessary, to achieve an impact: (1) when the focal problem is complex and important to the community from which the potential network will be drawn; (2) when the knowledge, expertise, access to target populations, and other components of potential solutions are distributed across different organizations; and (3) when the problem has no readily apparent solutions, requiring the iterative discovery and development of solutions. In such circumstances, a network approach allows stakeholder organizations to quickly mobilize diverse sets of resources and human talent to tackle both individual and broader systemic change, and develop enduring relationships that support a sustained flow of activities.

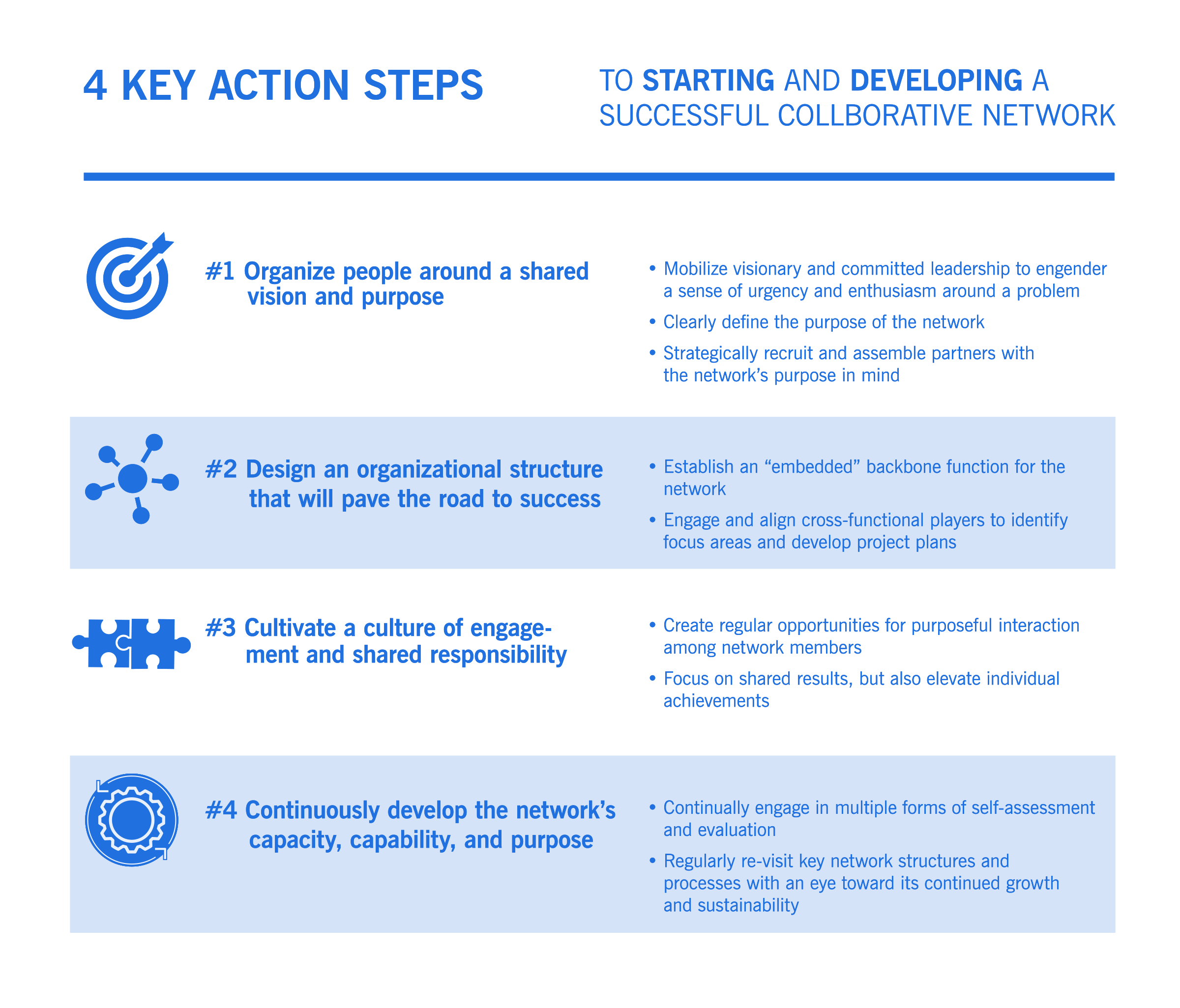

To achieve these benefits, networks require careful planning and management. Through our research, we identified four key action steps to starting and developing an effective network, described in the graphic below. It is important to note that establishing a highly functioning network—an important and perhaps necessary step—is not the same as achieving the broader practical goals with tangible social impact for which the network was created. While it may be more challenging than assessing the health of the network’s relationships and processes, developing ways of assessing whether the network is furthering its underlying purpose is an important component of this more fundamental form of network success.

Introduction

As digitization, automation, and artificial intelligence reshape industries in just about every enterprise imaginable and transform people’s lives in profound ways, leaders across public and private sectors are looking to tackle the new challenges of our times while learning to navigate an uncertain future.

In postsecondary education, in particular, the pressure to innovate in response to the changing times is high. The number of traditional-aged college students is declining across most of the country, and the new generation of students is more diverse in terms of race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status than any previous cohort of students.[1] At the same time, large and increasing numbers of working adults—many of whom tried and struggled in college previously—are seeking additional education and training to advance their careers and help them adapt to broader economic and technological trends.[2] These demographic shifts are exposing a dissonance between the core assumptions and features of many existing postsecondary education providers and the needs of modern students and our economy. Even as policymakers, employers, and the public expect higher education institutions to meet these evolving needs, and are looking to new providers to fill gaps, state and federal investment in postsecondary education and training is lagging behind other demands.[3]

In short, postsecondary education faces a daunting set of external challenges—as well as exciting opportunities. There is the potential to achieve a postsecondary education and training ecosystem that is more tightly aligned to student and economic needs, more equitable in offering opportunity to learners from lower-income and underrepresented minority backgrounds, and more efficient and affordable. To reach this potential, incumbent organizations must make fundamental changes to the way they operate—including how they interact with new players in the space—with few and sometimes declining resources to do so.

Recognizing that these challenges and the potential solutions go beyond the boundaries of their own institutions or organizations, some postsecondary education leaders and training providers are turning to a deeper level of collaboration. Building on the foundation and lessons from past models to meet new challenges, these collaborations—which we refer to as higher education-focused networks—have become increasingly important in the 21st Century (see Sidebar 1 for examples of relevant past collaboration models). Oriented around complex, crosscutting problems of improving student success and social mobility, enacting structural and cultural change, and managing overlapping organizational responsibilities, these higher education-focused networks develop cross-organizational relationships that iteratively generate new ideas and processes within and across the participants to address those problems. The networks we focus on have the potential not only to change practice within their member organizations, but also to have an impact at scale on their ecosystem.

This playbook discusses the conceptual grounding for higher education-focused networks and offers a set of key action steps on how to start and develop a successful network. It is based on a review of previous relevant research on collaboration, interviews with more than twenty network leaders, policymakers, and higher education scholars, as well as insights gleaned from a convening we hosted on the topic in February 2019 (see Appendix B for more information on the authors of this report and their research process).[4]

The playbook is organized around four core questions:

-

- What is a higher education-focused network?

- Why and when might postsecondary leaders and their partners consider a network approach for addressing social challenges or developing solutions?

- What are the key features, processes, and considerations for starting and developing a successful network?

- What can we learn from some of the networks that have successfully employed these strategies?

Sidebar 1: The Founding Days of Early Forms of Higher Education-Focused Networks

The idea of college and universities cooperating with one another was largely an untested idea until the turn of the 20th century, and the growth of institutional and community-based networks is largely a recent phenomenon, as campuses navigate the financial and demographic forces bearing down on higher education. While most alliances in higher education were designed around geography or for transactional purposes, some alliances brought institutions together to address specific issues as a group.

The Association of American Universities (AAU) was founded in Chicago in 1900, with 14 of the nation’s leading doctorate-granting institutions collaborating to consider “matters of common interest relating to graduate study.”[5] In the waning days of World War I, 14 higher-education associations formed an emergency council to ensure the United States had enough technically trained military personnel. First named the Emergency Council on Education, and later renamed the American Council on Education (ACE) it eventually became the umbrella group representing higher education institutions.[6]

As higher education started to grow in the years after World War II, thanks to the G.I. Bill, new alliances formed so that institutions could share resources and keep up with the ever-expanding needs of the library and their researchers. Two of the most well-known alliances in higher education came together in the 1950s. The Ivy League was created as an official athletic league during that time, [7] and the presidents of the Big Ten athletic conference agreed to form the Committee on Institutional Cooperation, or the CIC, to strengthen their institutions against what they saw as a growing competitive threat for research dollars, students, and faculty from universities on the east and west coasts (the CIC was later renamed the Big Ten Academic Alliance).[8]

Defining a Higher Education-Focused Network

With the rise of social media sites like Facebook and LinkedIn, the word “network” is now a commonly used term. Our common understanding of a network refers to a system of interconnected people or things. When it comes to higher education-focused networks, such a system includes colleges and universities, K-12 schools and businesses, philanthropies, and governmental or community-based organizations.

One of the issues we struggled with early on in our research was answering this question: What makes a network a network rather than simply a group of people working together? We adopt Peter Plastrik and his colleagues’ definition as a basis for framing and scoping our discussion of networks in this playbook. [9] They define a network as a group of “individuals or organizations that aim to solve a difficult problem in the society by working together, adapting over time, and generating a sustained flow of activities, and impacts.”[10] A network is “generative” because it serves as a platform for generating multiple ongoing activities with an aim to achieving change that results in social good. Its members are not merely connecting or sharing information, but forging “powerful, enduring personal relationships based on trust and reciprocity” and undertaking numerous activities that emerge over the years of working together.[11] A network stands in contrast to other forms of collaboration, such as an alliance or coalition that represent the temporary alignment of organizations that will disband once its specific objective has been met.[12] A network is also different from a member association, which doesn’t necessarily require its members to develop highly entangled relationships and collaborations and is mainly intended to pool resources to provide various member-based services.[13]

Although the literature makes a clear distinction between these different forms of collaboration, we found it rather difficult to catalog some of the existing and emerging collaborative groups squarely into specific forms or types–their differences are not always clear-cut and they evolve rapidly in response to their changing needs and goals. For example, a group may form a temporary alliance to achieve a specific goal, but then morph into a longer-lived network with a broader set of purpose and goals over-time as it gains momentum and garners community support.[14] Similarly, a group that was originally conceived as a network may become a non-profit organization to continue pursuing its mission with a more streamlined and sustainable funding model, even as it still maintains some of the core features of a network.

Given the complexity of the collaboration landscape in higher education, as well as the ever-evolving nature of many of these groups, we purposefully explore collaborative groups that embody the key features of a network, irrespective of what they call themselves or whether they take on different organizational forms and shapes. The key network features we focus on include: (1) tackling a prominent social problem or challenge in the field by working together with a group of individuals and organizations; (2) adapting the group’s approaches, strategies, structures, and goals over time in response to new learning and changes in the environment, and (3) generating a sustained flow of activities and impacts with the aim of achieving change that promotes the social good at some level of scale (e.g. local, regional, or national).

It is worth noting that even though networks are often contrasted to member-based associations in the literature, many of the established associations are creating, incubating, and/or housing networks as a means to align and support their members in advancing their shared missions and goals. One notable example is Powered by Publics, a recent initiative of the Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities (APLU). The initiative brings together a large group of “change-ready” APLU member institutions to work within smaller clusters to implement evidence-based strategies and incubate new solutions for student success.[15] Another example is the American Association of State Colleges and Universities’ (AASCU) Re-imagining the First Year of College (RFY) project—a set of 44 AASCU member institutions that have committed to working together over three years “to develop comprehensive, institutional transformation that redesigns the first year of college and creates sustainable change for student success.”[16]

While we researched numerous collaborative groups to inform this playbook, we selected seven networks that emerged in the 21st Century in the U.S. and have robust documentation of their efforts for more intensive profiles, to better illustrate the organizational structures and processes of networks (see Appendix A for full descriptions):

-

-

- Achieving the Dream (ATD): a national network of community colleges that evolved into an independent non-profit organization, with a mission of closing achievement gaps and driving student success in the community college space using a continually evolving, field-informed framework to guide holistic curricular and institutional changes;

- American Talent Initiative (ATI): a coalition of private and public four-year institutions that have pledged to expand opportunities for access and success for talented low- and moderate-income students;

- Graduate RVA: a regional partnership of higher education institutions in the greater Richmond, Virginia area, which spun off from a longer-standing cradle-to-career network to significantly increase regional postsecondary completion efforts as a means of reducing poverty and improving social mobility in the region;

- The Long Beach College Promise (The Promise): a long-standing partnership between the major education institutions in the city of Long Beach, California, that has recently expanded its programming and partnership to further extend the promise of a quality college education to every student in the region;

- The University Innovation Alliance (The UIA): an alliance of 11 public research universities across the nation aimed at significantly increasing the number of low-income students, first generation students, and students of color graduating with quality college degrees and catalyzing systemic changes in the entire higher education sector through active collaboration and information sharing;

- Unizin: a growing consortium of higher education institutions dedicated to co-developing and advancing a robust digital education and collaboration infrastructure to empower faculty and students through improved access to learning materials and rich data;

- UpSkill Houston Initiative: a regional partnership among a broad spectrum of players from business/industry, education, non-profit, and public sector seeking to increase awareness of high-growth career paths in the region and train individuals with the skills necessary for success, using curricula informed and developed around industry demand.

-

As visible from this small collection of featured networks, colleges and universities are not necessarily the only or even primary type of organization leading such efforts in the field of higher education. Some of the networks that we highlight, such as the Long Beach College Promise, include partners in the K-12 system, the local government, as well as local businesses. Others, such as the UpSkill Houston Initiative, feature workforce development organizations, industry leaders, and employers in primary roles, with colleges and universities serving in supporting roles.

Starting a Network: When and Why?

When is it a good idea to start a higher education-focused network? This depends heavily on the complexity and relevance of the problem at hand in the context of the larger higher education landscape of the time, how expertise and resources are distributed across the ecosystem, and the feasibility of starting a network that may involve various “readiness” factors on the part of key leadership and potential partners.

A network approach is suited to situations in which (1) the focal problem is complex and important to the community from which the potential network will be drawn; (2) the knowledge, expertise, access to target populations, and other components of potential solutions are distributed across different organizations; and (3) when the problem has no readily apparent solutions, requiring the iterative discovery and development of solutions.[17] As evident from the problems being tackled by the seven featured networks we outlined above, many of the “thorny” problems in today’s postsecondary education ecosystem center on improving social mobility opportunities for diverse learner populations, especially those learners who have been historically excluded from or underserved by higher education.

Now, why might postsecondary leaders and partners want to consider taking a network approach to solving their difficult problems? There are numerous potential benefits of networks that cut across individual and collective domains; we describe three benefits most relevant to the present needs of postsecondary players:

-

-

- Quickly mobilize diverse sets of resources and human talent into novel combinations not otherwise available to single individuals or organizations. In order to navigate the intractable problems of our times (e.g. achievement gaps, skills gap, inequitable opportunities and outcomes), multi-faceted solutions that tap into expertise, knowledge, and connections of many individuals and organizations are needed. This requires a deliberate effort to facilitate better communication, information sharing, and problem solving between different individuals and entities that have traditionally operated in silos to see how their individual work fits in with those of others, align their resources and efforts, and together navigate the various forces that are shaping and re-shaping our economy and society. For example, employers and education providers can pool their expertise, resources, and talents to not only improve employer signaling of industry demands and education providers’ curriculum offerings to that end, but also devise new strategies and solutions not imaginable or practical for either party outside such a collaboration. By strategically assembling novel, flexible, and potentially higher-performing combinations of human talent and relevant resources, a network serves as a powerful tool for addressing thorny challenges in the field more effectively and nimbly.

- Address both individual and broader systemic change by leveraging the power and influence of large numbers. Network participants are often distributed and large in terms of numbers, and the strength in numbers is not to be underestimated. This is readily evident for the many individuals and organizations already taking advantage of cooperative procurements to obtain quality goods and services at an affordable rate through large group contracts, for instance. Numbers exude power and imply significance, beyond group contracts. Several of our interviewees noted that it is much easier to build a case for broad and systemic change when a large group of individuals and organizations come together with a single voice around a focused goal.

- Develop and strengthen enduring relationships that support a sustained flow of far-reaching activities and impacts. The relationships built and developed through a network over time can potentially have a far-reaching impact that goes beyond the network itself. Successful networks can have “ripple effects” of continuing and spreading their learning to others in and around their social circles, allowing information, ideas, and resources to move more quickly and widely than they would in other forms of collaboration, influencing others’ work in profound ways.

-

It is important to note, however, that a network approach to solving problems of student opportunity in postsecondary education is not always advisable. There will be circumstances when the costs of a network approach outweigh its benefits, especially when the time and resource commitment for coordinating and collaborating is not justified by the anticipated impacts and benefits of the effort. There are also challenges in higher education where a change in government policy may be the only viable long-term solution. And some problems might be adequately addressed through simpler forms of inter-organizational cooperation instead of a network (e.g. shared services, or short-term partnerships).[18]

Even when a network approach makes sense on paper, certain conditions must be in place to make it feasible. These include the leaders’ willingness to allocate resources and political capital to support a network, as well as potential partners’ willingness to commit to a long-term relationship and invest time, money, energy, and other resources. We delve into these, and some of the other conditions that need to be met when forming and developing a successful higher education-focused network, in later sections.

Successful Network vs. Network Success

It is worthwhile at this point to note an important distinction: a successful network does not necessarily imply that the network has achieved substantive network success. We define a successful network as one that has effectively brought together diverse players who have pledged to collaboratively tackle a complex social problem, and has established a good infrastructure for member engagement and collaboration to that end. Network success, on the other hand, refers to the network meeting its stated goals or fulfilling its ambitious purpose (e.g., improving student success and social mobility). While establishing a successful network may well be one important aspect of network success—and perhaps a necessary one—the higher education-focused networks covered in this playbook have broader practical goals with tangible social impact. The recommendations we present next in the form of key action steps focus on starting and developing a successful network, rather than achieving network success, though the former may be an important step to achieving the latter.

The network managers and experts we interviewed shared the challenges and complexities of evaluating a network’s impact and, by extension, its success. A network is a moving target that adapts rapidly to changes in its context, such that its intermediate goals and the best means by which to assess progress toward them are dynamic and fluid. Moreover, due to the numerous players that move in and out of a network throughout different phases of its life cycle, as well as its intersecting and overlapping activities, the network may have a chain of impacts that are not readily visible, trackable, or even anticipated. Finally, because it often takes a long time to build a successful network that can yield any positive impact, premature assessments of network success run the risk of stymieing progress and viability. With that said, as we describe in more detail throughout the playbook, developing an appropriate definition of substantive success for a particular network, as well as a strategy for assessing it in some way, are important checks to ensure the network remains focused on its underlying purpose and that the very act of maintaining the network itself does not become its main purpose.

Key Action Steps to Starting and Developing a Successful Network

One of the goals of collaborative networks is to bring about transformative change in their community, field, and/or sector. Change is fundamentally a people process, and in order to achieve and sustain a change, it must be deeply embedded in people’s mindsets, practices, and behaviors at every level. Building a network involves making appropriate decisions and actions based on an understanding of the evolving situation. The success of a network does not rest on one successful initial negotiation to build membership and technical capacity; it also relies on constant negotiation with the changing nature of the organizations and individuals involved.

Below we present key people-centered processes of successful higher education-focused networks, organized by four high-level action steps, from the starting of the network itself to its path towards continued growth and sustainability. We present these steps in a loosely chronological sequence because they build on each other, with the earlier steps often helping to lay the foundation for the next steps. Conversely, shortcomings in a given step can impact the success of subsequent steps and the network’s overall success. We recognize, however, that in reality, a network’s developmental path will be more dynamic and nonlinear than what we portray here. To contextualize these action steps and their main components, we feature specific examples from the networks we studied. We encourage readers to think about the interdependent as well as evolving nature of these steps and processes, and link them back to their own collaborative efforts, and to the implications they may have for fully realizing the network’s collective potential.

Action Step 1: Organize People Around a Shared Vision and Purpose

Some networks arise organically, rooted in deep historical and interpersonal connections that are rarely visible to the public eye. These roots engender a sense of vision and purpose that define what the network’s members are committing to do together. For other networks, that shared vision is cultivated intentionally among a group of people or organizations that lack the same historical relationships, but are nevertheless bound by a common goal, region, or set of constituents. In either case, simply having those relationships or common purpose is insufficient to start a successful network. That initial connection must be nurtured and transformed into a network structure through a process carefully designed and executed by a team of highly committed and enthusiastic leaders.

Mobilize visionary and committed leadership to engender a sense of urgency and enthusiasm around a problem in the field

Every successful postsecondary network that we have observed has a multi-person team of champions that plays a pivotal role in its birth and early development. These champions are individuals with active roles in various capacities in and around postsecondary education, such as college and university presidents, chancellors, and administrators, as well as industry leaders, philanthropy officers, policy makers, researchers, advisors, and community thought leaders. They have a deep understanding of the lay of the land and can leverage their interpersonal connections and effectively use research and data to create urgency and enthusiasm among stakeholders and the public around a particular problem and advocate for change that requires a concerted effort of diverse players. There are at least two types of champions whose presences are critical in the formation phase of a network: ideation champions and staff champions.

Ideation champions are individuals often at the CEO, presidential, or other senior executive level, who champion ideas or concepts that lead to the creation of a new network or significant expansion, revamping, or restructuring of an existing one. Highly integrated, visible, and respected in their respective community or field, these champions have the ability to create legitimacy and authenticity to motivate others to support their vision and share the experience. They also play a critical role by doing a lot of the heavy lifting, including capitalizing on the urgency and enthusiasm they help create to mobilize seed funding to support the successful formation and launch of a network.

How do ideation champions find each other and successfully bring others on board? Typically, they find each other through the plethora of local, regional, and national venues and professional and social networks, which are fertile ground in which to plant the seeds of a collaborative network. The examples below illustrate how existing connections in the higher education community fostered the initial championing of two such networks.

-

-

- Through their respective institutions’ affiliation with the Big Ten Academic Alliance, where collaboration is the norm,[19] Brad Wheeler of Indiana University and James Hilton of the University of Michigan started conversations that led to their co-founding of Unizin – a network formed in response to the rapid growth of higher education technologies. The pair had over a decade of experience working together and with many other institutions in building collaborative digital models and services,[20] and had been particularly vocal about urging research universities to move away from perpetual silos and toward “intentional interdependence” to find more effective solutions to complex problems in higher education.[21] Together they organized a series of conversations among their circle of colleagues and friends, many of whom were in charge of the information technology strategy and systems in their respective institutions, to come together around the Unizin vision—to enable universities to collaborative develop, advance, and maintain a shared digital education infrastructure rather than rely on proprietary educational products and services with adverse impacts on educational quality.

- President Michael Crow of Arizona State University invited a small group of presidents and chancellors to engage in a discussion about collaboration and scale on the heels of the Next Generation University project published by New America. [22] After the publication of the report, he organized several meetings to bring together university presidents, chancellors, and other campus leaders to discuss its findings and implications, building a sense of urgency for action. These conversations ultimately ignited motivation and support from the field to form the UIA with a goal of increasing graduation rates among low-income students by identifying and scaling successful student success interventions in a group of large public research universities in the U.S.

-

Moreover, it is important to note the value of staff champions, who champion the substantive work of a network, including shepherding its formation, development, and ongoing development. Some staff champions may work closely with ideation champions in the early stages of a network to assist with its formation and launch, working “behind the scenes” to continue building a sense of urgency for the proposed problem and garnering enthusiasm and support from the field. One of their key roles is building, and then strengthening, the network’s connective tissue by managing relationships with and among partners and members, regularly reinforcing the shared values and goals, building consensus, and driving the focus of participants’ efforts toward the network’s collective goals. We will further discuss the role of staff champions in later action steps.

Clearly define the purpose of the network

One of the first tasks of network champions is to establish and communicate a clearly defined purpose for the network—its raison d’être. This purpose will guide and inform how the network is designed and built, including the key processes of selecting network partners and developing the network’s strategic design. Establishing a network purpose can be especially challenging when there is no clarity on the kinds of activities participants will be engaged in and the kinds of outcomes they will be producing.[23] It is therefore important to develop a purpose that is broadly applicable, but focused in terms of the problem it aims to tackle, with the recognition that it may need to be adjusted as the network matures and evolves over time. For some networks, agreeing on a set of shared performance measures can further help aligning members around the shared purpose as well as a sense of direction while providing a system of accountability.

While the purpose of a network can take different forms and shapes depending on the local context, specific problem at hand, and target beneficiaries of its activities, the underlying principle must be inclusive and collaborative in nature. In other words, the purpose of the network must be defined in such a way that it necessitates the alignment and contributions of involved parties to drive an intended impact, as shown in the following examples.

-

-

- The American Talent Initiative (ATI), a collaboration between the Aspen Institute’s College Excellence Program, Ithaka S+R, and a growing alliance of colleges and universities, was founded with a single purpose in mind: expand high-quality postsecondary opportunity and access to talented low- and moderate-income students across the nation. To that end, the network champions set an early and ambitious national 2025 goal of attracting, enrolling, and graduating an additional 50,000 lower- and moderate-income students at over 300 high-performing four-year colleges and universities in the country.[24] The purpose of forming ATI, as well as its shared performance measure, are collaborative in nature by design, as they require the partners and member institutions to work together to bring about a scale of national change that no single institution can do alone.

- The Long Beach College Promise (The Promise) is one of the signature initiatives of the Long Beach Education Partnership,[25] which was first established in 1994 as part of the larger community-wide effort to tackle economic and demographic challenges facing the city at the time. Born in 2008 out of the successes and strong foundation of the existing partnership, the Promise focused on expanding opportunity for all Long Beach Unified School District students by eliminating barriers to student success in every step of their education pathways from pre-K to college and later on to career and life. By design, the Promise’s purpose requires rigorous alignment of mission, curriculum, standards, and practices across the district’s three education systems—its public school district, community college, and state university.

-

Strategically recruit and assemble partners with the network’s purpose in mind

Another critical task of the champions in the early stages of a network, which must be approached with a high degree of intentionality, is recruiting the “right” partners who can increase the network’s value and, ultimately, its chances of success. Network partners include the institutions, schools, and organizations, and relevant individuals within them, who will carry out the network’s actual activities (e.g. institutions that educate or train students), as well as those that directly support them to that end (e.g. a governmental office, an organization serving a core supporting function to the network, or an actively engaged funder). There are at least three qualitative criteria against which network builders can assess a potential partner’s fit: partner compatibility, complementarity, and capacity.[26] While all three elements are important to successful partner selection, the degree to which they should be emphasized varies depending on the purpose and structure of the network, the context in which the network resides, as well as its maturity in the field.

As will be exemplified in the upcoming sections, different networks have different needs based on their purposes and context, such that a source of compatibility for one network may be a source of incompatibility for another (see Sidebar 2 for how the three elements of partner selection criteria played out in the formation of the University Innovation Alliance). It is important to note that even when these three criteria are met, strong competition among potential network partner organizations at a high level may have direct implications for their own viability and sustainability as independent entities in today’s competitive environment. The interests of the individual partner organizations may undermine effective collaboration and the interests of the network. With that said, as we discuss later, there are strategies to promote “healthy competition” among network partners and their members that can be beneficial to those involved and to the network as a whole.

Partner compatibility refers to the similarity and close alignment among partners’ core vision, level of commitment and trust, organizational culture, values, norms, and working styles, which can make it easier for partners to readily build rapport with each other and more effectively cross their institutional boundaries to collaborate. Compatibility is especially important when a high level of entanglement among partners is needed—when the work requires partners to rely on each other, share risks, and “co-labor” to accelerate their goals. Some of our interviewees noted that one important area for compatibility is the pace at which higher education institutions are leading or lagging each other in campus innovation or transformation. If a “readiness” for institutional change is central to carrying out the network’s purpose, differential paces among partners may create a significant hurdle to robust collaboration. Recognizing this, Unizin, for instance, chose to form with a limited set of highly compatible institutions—four public research universities that were willing and able to take similar risks on a similar timeframe and make a significant financial investment at the outset to help build the initial infrastructure and process for Unizin’s ecosystem of digital education systems and collaborations. [27]

Partner complementarity refers to the degree to which partners can contribute a non-overlapping set of expertise, skills, knowledge, contexts, and/or resources to support the network’s efforts. The complementary nature of partners’ contributions can further validate the importance of their collaborative relationship, and if leveraged and integrated well, can yield powerful synergistic outcomes. Since scale is a key characteristic of higher education-focused networks, some level of complementarity will need to be built into partner composition to expand the network’s reach and impact. How and when complementarity should be achieved varies greatly across networks. By way of example, Graduate RVA by design needed to include four-year and two-year institutions due to its focus in part on credit transfer success.[28] As the network evolved to focus more directly on reducing racial equity gaps in attainment, it needed to further prioritize complementarity by inviting partners with a strong record in enrolling and supporting underserved students, in this case African American students. To that end, the network sought a regional HBCU partner for complementarity in that regard, while also maintaining compatibility by selecting a public institution with a demonstrated interest in promoting transfer success and aligning practices across the region’s public institutions.

Finally, partner capacity in the narrow sense refers to partners’ ability to dedicate appropriate and timely resources (e.g. expertise, skills, or knowledge) to successfully carry out their collaborative projects. Partner capacity may be easier to gauge and plan for in shorter-term projects focused on a discrete set of activities (e.g. data sharing among a small group of institutions for a certain duration of time), but more difficult in highly mission-driven projects with ambitious goals that require sustained partner engagement for a long period of time. In the latter case, the definition of capacity is broadened to include a partner’s leadership commitment to the shared vision, community buy-in and engagement, and adequate institutional infrastructures, policies, and practices to support the network’s particular goals—all of which are important prerequisites for taking a comprehensive and sustainable approach to improving student success at scale.[29]

Sidebar 2: Balancing partner compatibility, complementarity, and capacity in the formation of the University Innovation Alliance (UIA)

The background research that catalyzed discussions that would later lead to formation of the UIA identified six high-performing public research universities that were expanding enrollment while improving student graduation rates in cost-effective ways. Of those, four institutions joined forces with a group of other campuses to form the UIA. These institutions were compatible on a number of criteria, including: a history of national service and an egalitarian commitment to social mobility for students; previous experience in scaling innovations from small pilots to university-wide programs; and a shared commitment to developing scaling methods for higher education; as well as their willingness to partner and share information.[30]

In terms of complementarity, the 11 institutions collectively represent major regions of the U.S., with each having demonstrated expertise serving different student populations. Each institution is situated within a distinct state context, with differences in state funding, local demographics, governance arrangements, and more. According to the UIA’s prospectus, these differences make its member institutions particularly well-suited for developing scaling methods for higher education “in part because [they] represent the demographic, geographic, and economic diversity of the country.”

Finally, the willingness of the partner institutions’ presidents and chancellors to commit to a number of steps has contributed to their collective capacity to iterate and scale campus innovations together: Each institution has agreed to match funds raised for the UIA’s activities, appoint designated senior administrators to shepherd projects related to the network’s goals, and hire full-time paid fellows dedicated exclusively to its activities.

It is important to keep in mind that the partner fit assessment criteria we outline above could be used in ways—whether intended or not—to exclude certain groups or individuals from participating in these collaborative activities, especially those from minority and underserved backgrounds with limited resources, thereby reinforcing and exacerbating the gaps that exist between haves and have-nots in higher education and throughout the nation.[31] One of the key benefits of network participation includes access to knowledge and relationships (e.g. social capital) that are important elements of upward social mobility for both individuals and communities.[32] Network builders and community leaders must think critically about these issues in their partner selection and assembly processes.

Action Step 2: Design an Organizational Structure that will Pave the Road to Success

Networks require an organizational structure that will infuse the shared vision and coordinate activity at the partner institutions and organizations, so they can collectively own and lead the network’s efforts. This structure must account for the deep collaboration and sustainability needed to maintain the network, even when it faces unanticipated challenges (e.g. leadership turnover). A large part of this process involves the strategic engagement and alignment of cross-functional players at multiple levels both within individual organizations and across the network through a strong central coordination mechanism, including empowering individuals outside of traditional leadership roles to contribute their expertise and knowledge to lead different parts of the change process. As we have alluded to in the previous action step, the role of staff champions is essential in this stage to help pave the road for successful organization of a network.

Establish an “embedded” backbone function for the network

Every well-run network we studied has some form of backbone function that engages, aligns, and integrates its members into a coherent whole.[33] While there does not appear to be one best model for designing and instituting a backbone function for a higher education-focused network, it is clear that having such a function is necessary to hold the group together, keep it on mission, and support its growth over time.[34] A backbone function can ease the administrative burden of running the network and allow the group to get up-and-running faster and move further toward its goals. The role of a backbone function will vary depending on the context, scope, and maturity of a network. Also, its hosting entity, format, or even focus may shift over time as the purpose and goal of the network evolve through different phases of its life cycle. As such, a backbone should not be viewed as a simple plug-in solution, but rather as a function that is ideally generated and adapted based on the network’s unique context and evolving needs.[35] There are at least two approaches through which a backbone function can be integrated into higher education-focused networks to maximize their success:

-

-

- An internal and embedded approach utilizes full-time leadership staff and a mix of other in-house staff or consultants to provide core functions to the network. It is internal because the staff serving the backbone function are directly affiliated with the organizations or institutions that are key network members, and also embedded because their main job is dedicated to carrying out the work of the network. This approach seems to be a go-to strategy for many higher education-focused networks, particularly those involving a somewhat controlled number of participants, who often have a shared history of missions, institutional or organizational type, and regional focus. It is also a relatively inexpensive way to quickly get a network off the ground with a generally light team of central administrative staff (e.g. Graduate RVA, The University Innovation Alliance and The Long Beach College Promise).

- An external, but embedded, approach utilizes a third-party organization to provide the key expertise to the network and act as a monitor to evaluate its success. It is external because the staff of the backbone function are not directly affiliated with the institutions or organizations that are key members of the network, but still embedded since these third-party organizations often have deep professional and interpersonal ties to the network. This approach seems to be preferred when the size of the network (e.g. number of participants) and/or diversity of its members (e.g. participants from different organizational types, communities, sectors, fields) are very large, or when the network itself lacks sufficient resources (e.g. skills, expertise, staff time) to develop an internal backbone function. In some cases, this role might be filled by an existing non-profit organization that already has the administrative infrastructure, connections, and expertise necessary to support a network (e.g. the Greater Houston Partnership serves as the backbone for the UpSkill Houston Initiative; the Aspen Institute and Ithaka S+R serve as the backbone for the American Talent Initiative). In other cases, this may involve an entirely separate full-scale organization created specifically for this function (e.g. Achieving the Dream, Unizin). Funders may also fill this gap by providing resources and assisting to align partners and guide their activities (e.g. Lumina Talent Hubs Initiative).[36]

-

Leadership exercised by the backbone function can play an important role when it comes to making progress toward achieving a network’s end goal. The key characteristics of effective backbone leadership include being exceptional collaborators and relationship builders.[37] Their communication strategies are aimed at helping members remain focused on the end goal, and continue to think about their work in the interest of the collective, not just in the interest of an individual member. Throughout the lifecycle of a network, the backbone function plays a variety of different roles, including but not limited to:

-

-

- An accelerator to shorten the time to the goal.

- An arbiter to provide neutral expertise and guidance.

- A bridge builder to connect cultures that would normally not work together.

- A convener to connect groups of people to collaborate, form relationships, or develop new partnerships.

- An evaluator to establish shared metrics and evaluation processes.

- A funder to set a high-level vision and provide the resources necessary to mobilize efforts.

- A fund raiser to help mobilize funding for the network.

- A guide to help analyze capacities and needs of partners and/or members.

- A project manager to assist with coordination and completion of projects on time within agreed-upon budget and scope.

- A quality and accountability expert to fill where the main participants don’t have the capacity.

-

Regardless of the backbone approach taken—whether internally built or externally sourced—it is critical that the backbone function remains lean and mission-aware. This allows it to (1) avoid replicating the legacy and bureaucratic structures of individual partners; (2) continue to invest in the development and capacity of individual network members, and perhaps most importantly, (3) not overshadow the network partners by becoming the public-facing, de facto stand-in for the overall network.

Engage and align cross-functional players to identify focus areas and develop project plans

At the individual member organizations, leadership involvement at the top is undoubtedly important, but it alone is not sufficient for creating deep and sustained change. People across departments and at multiple levels of an organization’s hierarchy, with or without formal leadership titles, must be aligned around a shared vision and work together to move the networks’ agenda forward. Without this kind of alignment and cohesiveness, the initial sparks of enthusiasm that often accompany the beginning of a network will likely remain small and ephemeral.

In their recent paper on the topic, Adrianna Kezar and Elizabeth Holcombe argue that today’s higher education leadership challenges necessitate new forms of leadership—ones that move away from the leader-follower binary type to recognize the importance of many leader types across the organization that are not necessarily limited to those in positions of authority.[38] Research has found that this type of shared leadership allows organizations to quickly learn, innovate, perform, and adapt to various challenges in today’s complex environments. Engaging and aligning key cross-functional players at multiple levels enable institutions to garner broader community buy-in, and create the conditions that are conducive for active member engagement, including peer mentoring and enforcement. This kind of “authentic engagement” is ideal for developing many important decisions and plans, particularly those whose success highly depend on collaboration among many stakeholders.[39] By bringing together multiple points of view to inform decisions, such broad-based engagement fosters a sense of legitimacy and shared responsibility among the key stakeholders in the change process early on and throughout, creating broader awareness of the network’s goals and activities and stronger momentum for change.[40]

-

-

- In the Long Beach College Promise, the superintendent of the Long Beach Unified School District and the presidents of the Long Beach Community College and California State University, Long Beach, together lead and govern the partnership. In addition, a leadership council, comprised of a convener and a steering committee made up of two senior representatives from each institution, serves as the link between the partners and shepherds different projects that directly contribute to the partnership’s goals. The leadership council capitalizes on the shared leadership of staff, faculty, and administrators across the institutions to design and devise project plans. For example, when forming working groups to create curricular pathways for students across the institutions (e.g. engineering, liberal arts, or health pathways), each working group would include faculty, academic advisors, counselors, and administrators with expertise with specific disciplines to lead various project efforts to fully understand students’ experiences along the academic pipeline. [41] This approach allows faculty members to contribute their classroom and curricular expertise, advisors and counselors to contribute their institutional policies expertise, and administrators to provide a macro-level perspective and appropriate support to individual working groups. This shared leadership approach, coupled with intersegmental and inter-institutional communication and collaboration, allows teams to collectively own the work and come up with solutions that best meet the needs of students across the three institutions.

-

Action Step 3: Cultivate a Culture of Engagement and Shared Responsibility

In addition to a strong organizational structure, networks require a highly aligned structure or process in place to further cultivate a culture of engagement and shared responsibility. This structure must be carefully designed and continually modified to foster trust among network members, enable them to co-create a shared narrative and group identity, and reinforce their motivation for participating in the network. As we noted in the first action step, the very purpose of bringing together different players through a network approach is to tackle a problem or challenge that no one organization can solve alone. As such, there must be ample opportunities for people to interact and collaborate to advance and move the network’s agenda forward. To maximize the group’s collaborative potential, these interactions must be purposeful, meaningful, and motivational—both at the professional and interpersonal levels.

Create regular opportunities for purposeful interaction among network members

Learning is a major incentive for collaboration, as individuals and organizations are always seeking new or different ways to improve their practices. Regular opportunities for interaction among different individuals or groups of individuals that engage in the network’s activities are key channels through which such learning can happen. Contextualized for the network’s vision and goals, such opportunities allow people to share ideas, as well as concerns and challenges, and support each other while also problem-solving together. These processes engender not only collegiality and a sense of belonging to the network, but also a sense of purpose—that they are part of something much bigger—and reinforce a shared responsibility for the network’s vision and goals. Individuals tend to crave these interactions, but they are difficult to create without strong leadership and coordination support—and backbone functions can play a crucial role around these efforts.

The meetings can be designed to enable both deep and broad learning, tailored for different groups of individuals, alternating between group and individual work, and encouraging collaboration and creative thinking. It is important for meeting organizers to keep in mind that time is a valuable resource for any kind of collaborative work, and therefore, must be tapped into strategically. Attention must be paid to both the frequency and quality of these meetings, and that the interactions they will generate are purposeful and useful from the perspectives of the individuals, subgroups, or the network as a whole.

-

-

- Unizin members are provided with ample opportunities to connect with one another in the digital spaces (e.g. blogs and webcasts) as well as in-person through both regular and ad-hoc meetings. As the group matures and its connectivity strengthens, members are developing new groups and subgroups to help drive their vision and work together to build out plans for Unizin. The biggest group is the Teaching and Learning (T&L) group which was formed by members passionate about and dedicated to student success and affordability measures. The group also has numerous subgroups around focused topics, including faculty development, accessibility, learning analytics, and more. The T&L group hosts bi-annual meetings that bring together learning technologists, librarians, and higher education leaders from the member campuses to form connections and help inform important developments and decisions for the broader Unizin community. Moreover, annual summits are hosted to provide a platform for members to share their research, workshop ideas, and see how their individual goals fit into the larger goals of the group.

-

Focus on shared results, but also elevate individual achievements

It is critical for a network to bring its members together around discussions of the group’s shared results. This process further cultivates shared responsibility across the group, and reinforces the mission and goal of the collaboration itself and collaborative process. Furthermore, sharing these results with a broader audience beyond the network can empower its members, strengthen their shared interests and connective ties, and attract more attention and support from the public. At the same time however, a narrow focus on the interests of the whole network can leave individual members feeling disconnected from the network and the value it provides them.[42] Elevating individual achievements at different levels—individual, team, specific collaboration within the network, or whole institution—is an effective strategy to promote and maintain member motivation, satisfaction, and performance. Networks greatly benefit from striking a healthy balance between recognizing and highlighting both the collective and individual successes of its members, and the backbone function can play a key role in facilitating this balance.[43]

-

-

- The American Talent Initiative (ATI) aims to enable collaboration among its member institutions that can yield the greatest benefits through a set of core strategies: reinforcing a sense of collective responsibility through a shared goal and regular progress reporting; using a cross-institutional perspective and research to surface and understand network-wide effective practices; elevating strong examples of progress at individual institutions through internal and public communications (e.g., research publications, media outreach, and internal presentations and newsletters); and facilitating communities of practice that coalesce members around focused goals and tailored strategies. The goal of these processes is to create conditions that inspire the network’s over 120 private and public four-year institutions to serve more talented low- and moderate-income students throughout the nation. According to a chancellor of an ATI member university, being in the network creates a “friendly competition” that incentivizes institutions to share their best practices and together accelerate their shared goals around student access and success.

-

Action Step 4: Continuously Develop the Network’s Capacity, Capability, and Purpose

Bringing about transformative change in a community, field, or sector is an iterative self-reflexive process that requires ongoing refining, tuning, and restructuring. Many healthy networks embed self-assessment and evaluation in their work to capture lessons, make course corrections, develop and test new approaches and models, and make continuous improvements. Ongoing assessment and regular self-evaluation enable networks to respond nimbly to shifts in their environment and to strategically pivot, as needed, to remain relevant and impactful in the field.

Continually engage in multiple forms of self-assessment and evaluation

Continual self-assessment enables a network to systematically track its development to manage its evolution, understand what it is achieving for its members and field as a whole, and identify areas for improvement and growth. When developing assessment plans and tools, it is important that networks avoid rigid and limited frameworks that focus too narrowly on the particular outcomes of specific processes or efforts, at the expense of capturing various aspects of the network’s developmental process for a more holistic picture of its performance. Network self-assessment is most effective when it considers indicators of impact at multiple levels, and is collaboratively designed with an eye toward developing a system-wide view of what different members are attempting and achieving. Broadly speaking, the two main areas of assessment include: (1) the overall health of the network and (2) its various measurable outputs.[44]

The overall health of a network can be assessed qualitatively by looking at whether it is evolving as intended. For instance, do its value propositions resonate with its members? How large and diverse is its membership? To what degree are members engaged and how is leadership shared and distributed across the network? What is its funding capacity? How capable is the network in engaging in continuous learning and adapting based on their new knowledge? How connected is the network to external partners who can directly support it, as well as its reputation and relevance in the field? Such information can be gathered through general observation, as well as direct communication with members and partners through formal or informal meetings, phone conversations, social media, surveys, site visits, and self-reflection. This type of “feedback” help networks evolve and address emerging challenges, and foster their continued growth and sustainability.[45]

-

-

- In July 2015, more than a decade after the inception of Achieving the Dream (ATD), then new president Karen Stout and her leadership team paused to assess ATD’s role and contributions to the field. [46] They concluded that it had stagnated; losing ground and relevance due to its long-standing model that was no longer novel or adequate for its goals in the present context. [47] As such, Stout led ATD through a strategy reset process, which involved engaging with community college presidents, program staff, founding funders and partners, and new ATD members, as well as revisiting reports and qualitative feedback from the past. This process pointed to “systems change” as key to helping community colleges achieve their ambitious student success agendas. This led to ATD shifting its focus from supporting colleges on discrete interventions to guiding them, through robust tools and services, in assessing and developing seven key institutional capacity areas to advance their whole-college transformation efforts to improve student success at scale. [48]

-

The measurable outputs of a network include quantifiable achievements and results. Such information can be gathered by developing specific metrics that measure various intended outcomes of the network as a whole, and/or specific members, teams, or projects. This includes, but is not limited to, the number of activities undertaken and completed as a group, the amount of funds raised and matched, as well as specific impact measures from intervention projects. As an example, the American Talent Initiative (ATI) annually collects quantitative student enrollment data to monitor its members’ collective progress towards meeting the 2025 goal of attracting, enrolling, and graduating an additional 50,000 lower- and moderate-income students. The ATI team also collects a set of qualitative data from its member institutions, including information on their impact frameworks and plans, to assess their success in engaging and aligning partners to the network’s goals, as well as inform on-going activities (e.g. informational webinars, workshop sessions, and member convenings), designed to further support their progress towards meeting ATI’s individual and collective goals.

Continuous self-assessment helps and encourages networks to continuously evaluate and adjust accordingly as needed. It is important for networks to formalize this process such that information from its self-assessments are used purposefully and strategically to guide the future of the network. By pausing and taking a breath, so to speak, networks ensure they do not run the risk of embodying some of the problems they are actually fighting —e.g., inertia, risk-aversion, and narrowly focusing inwards. Network anniversaries, milestone completions, leadership changes, and momentous shifts in the field are common triggers for self-evaluations, whereby networks revisit their purpose, structure, strategies, and overall impact or necessity. Through this process, networks may adapt or refine their purpose, develop a new strategy, bring in new partners, or even restructure their approach altogether. It is important to note that measurable network results can take a long time to bring to fruition, and may even shift over time from the original intent as the network evolves. Networks are dynamic and always evolving, so keeping an open mind toward multiple forms of ongoing and learning-oriented assessment are critical.

Regularly re-visit key network structures and processes with an eye toward continued growth and sustainability

As a network matures over time, and sees the need for its continued growth and expansion toward broader purpose and goals, its managers need to think more deliberately about the network’s operational model and strategies, with an eye toward sustainability. The sustainability model developed by Adrianna Kezar and Sean Gehrke provides a useful conceptual framework for considering a set of intersecting features to foster sustainability, which we adapt and describe further below, with examples and insights gleaned from our research:[49]

-

-

- Leadership onboarding, development, and succession planning. Leadership turnover is one of the key barriers to change initiatives in higher education,[50] and in order to sustain a network’s efforts even in times of leadership changes, it is important to have a formal process in place to onboard new leaders into the network and also to delegate authority to others in the organization, along with the necessary support and mentoring to continually develop their leadership capacities. For example, during her interview at California State University, Long Beach, President Jane C. Conoley met with leaders from the three education institutions and the city, including the former mayor, who asked a series of questions to gauge her interest and commitment to continuing and advancing the work of the Long Beach College Promise to ensure continuity of the effort. In addition to onboarding new leaders, it is important to have a process in place to bring in new generations of talented professionals who can add fresh ideas and a renewed sense of enthusiasm to help continue and expand the network’s work, and over-time fill the leadership roles necessary to provide a sense of stability and coherence for the network.

- A diversified and streamlined funding model. Stable funding is a necessary condition for a network to continue its efforts and have an impact in their communities. Many networks began with seed funding from philanthropies or other entities to support their formation, launch, and initial development, and then relied on additional grants of varying sizes to support a multitude of projects aligned with their missions and goals. However, relying exclusively on grant funding is not a sustainable model in the long run, since the grant application process itself is labor intensive and time consuming and doesn’t allow for more stable longer-term planning. Philanthropic foundations also tend not to support core operations of grantee organizations over an indefinite period of time. There are a variety of ways through which a network’s funding model can be diversified beyond grant funding. Some of these approaches include: (1) charging fees for services, including selling materials and resources, (2) having members “match” the funds raised to contribute to the resource pool,[51] and (3) developing other partnerships to create additional revenue opportunities. For example, Achieving the Dream (ATD) initially relied exclusively on philanthropic funding to support itself, but after becoming an independent non-profit organization in 2011 and re-strategizing its focus to providing coaching services to guide holistic institutional change at community colleges, 60 percent of its overall revenue now comes from fees for service and member institutions.[52] These changes in the funding model have enabled ATD to have a more stable business model, and hire a mix of full-time and part-time staff to support and expand its efforts.

- Human resources. Managing a network is not easy, and in order to foster its sustainability, sufficient human resources must be allocated, including formally designated staff time and other temporary arrangements with consultants, advisors, coaches, etc., to successfully undertake the required workload. Such human resources can help ensure that the goals are met and also capitalize on funding opportunities to keep a network financially viable. While a central, designated team of staff (i.e. backbone function) is an important feature of a sustainable network, a network can greatly benefit from bringing in other flexible combinations of talent at different phases of its life cycle to fill specific gaps and needs (e.g. skill, knowledge, connection, administrative function, technical support) to support its continual growth. For example, the University Innovation Alliance initially began with the commitment and endorsement of partner institutions’ presidents and chancellors, a group of designated senior administrators as campus liaisons, and an executive director. After its official launch, a fellows program was established to recruit and embed early-to-mid career professionals at each campus to coordinate activities and communication within and across the network’s institutions. The central UIA administrative team also hires external evaluators, consultants, and advisors as needed to support specific projects or activities.

- Formal process for gathering feedback and advice. It is important to have a formal mechanism in place for receiving feedback and advice from partners and members, as well as others in the field, to continuously improve the network’s capacities. Such feedback and advice can be gathered through multiple venues. Some of the common mechanisms that we have seen include advisory boards, steering committees, and working groups with experts and key stakeholders who can provide strategic guidance both globally for the network and also specifically focus on particular projects. For example, the UpSkill Houston Initiative facilitates employer-led, sector-specific leadership councils (i.e. construction council, petrochemical council) to gather advice and information from employers to help guide and align curriculum programming at regional education providers. Comprised of leaders across industries, education, non-profit, and public sector, these sector-focused leadership councils ensure that projects are designed to address the demand and skill challenges in each sector.

- Assessment and research. The formal process of assessment and research is important to keep monitoring the network’s impacts over-time and also to demonstrate its value in connection to its mission, goals, and members to bring in additional funds to sustain/expand its efforts. Successful networks over time generate a lot of activities and projects, and managers of networks may use both internal and external researchers to conduct formal evaluation of their specific projects and/or interventions. Network managers or other core network participants can be a resource for researchers in both the design and interpretation phases of an assessment and help enrich the focus and scope, based on their more informal assessments through multiple forms of feedback from its members and partners. In the case of the American Talent Initiative (ATI), annual data collection on enrollment and graduation across the member institutions allows the group to continually monitor their collective progress to date, and use that information to also guide ATI’s operational strategy and activities.

- A clearly articulated, co-developed, and continually evolving network strategy. Finally, it is important to have a clearly articulated strategy for a network that is co-developed by its key members with advice and support from other partners and experts in the field. The strategy must not be overly designed or stringent, to allow the group to stay nimble and flexible to changing demands and needs. Unlike classical organizational settings, which have a single authority structure and clear set of management tasks and activities, network settings take on a divided authority structure as well as a more complex set of actors, resources, and influencing conditions, many of which are difficult to anticipate and plan for well in advance.[53] Using strategic planning tools that are simple and easy to revisit helps the network more efficiently involve and engage a broader community in its work with a sharper focus.[54] For example, thanks to their nimble strategy, Graduate RVA was able to shift their approach from regional to state to effectively tackle a particular problem. Technology software and resource capacity issues had caused reverse transfer numbers in the greater Richmond to stall. To address this they shifted to a statewide approach, and engaged the Virginia Community College System Office (VCCS) and State Council for Higher Education (SCHEV) to develop a strategy for statewide implementation instead.[55] As more schools became involved in the reverse transfer work throughout the state, it then became easier to implement that process in the greater Richmond region.

-

Discussion

The challenges currently facing postsecondary education—e.g., shifts in learner demographics, perceived disconnect between education and work, and persistent achievement gaps between different subgroups of learners—call for more focused and deeper collaborations across multiple stakeholders and sectors to break existing silos and strategically align their efforts with a shared goal of improving success and social mobility of all learners.

As we have demonstrated through the key action steps presented above, developing a successful network requires patience and willingness to embrace emerging—and sometimes unexpected—outcomes. Because networks, by nature, have many moving parts and are ever changing and non-linear in their developmental trajectories, a high degree of commitment and buy-in at all levels of an organization and across the network are needed in order to ensure their operational success. A network cannot be simply viewed as a “side project”—in order to do it well, network leaders and participants must be very intentional and strategic about their ongoing management strategies across the board, including their internal and external relationships, various projects, staffing, and funding and revenue models. Also, a robust system must be put in place to capture and document learning that is happening at distributed sites to continually build on the collective understanding of the network’s evolving work and to develop participants’ capacities to further advance their goals.