Setting a North Star

Motivations, Implications, and Approaches to State Postsecondary Attainment Goals

-

Table of Contents

- The State of States’ Attainment Goals

- Making the Case Through Internal and External Communications

- Engaging Key Stakeholders in Supporting and Adjacent Departments, Divisions, and Sectors

- Developing a Coherent Vision and Comprehensive Strategies to Meet the Goal

- Identifying Priorities and Key Interim Milestones and Regularly Evaluating and Reporting on Progress to the Goal

- Conclusion and Remaining Questions

- Endnotes

- The State of States’ Attainment Goals

- Making the Case Through Internal and External Communications

- Engaging Key Stakeholders in Supporting and Adjacent Departments, Divisions, and Sectors

- Developing a Coherent Vision and Comprehensive Strategies to Meet the Goal

- Identifying Priorities and Key Interim Milestones and Regularly Evaluating and Reporting on Progress to the Goal

- Conclusion and Remaining Questions

- Endnotes

Higher education attainment goals can serve as a “north star” to guide states’ postsecondary policies, investments, and agendas. The extent to which state attainment goals lead to substantive improvements in college-going rates, college graduation rates, postsecondary credential attainment rates, and reductions in labor market skills gaps is as yet unclear. Further, the likelihood a state will meet its attainment goals varies by state and depends on contextual factors that are within and outside the purview of the education sector. In this issue brief, we discuss the motivations, implications, and approaches states are taking to set and achieve their postsecondary attainment goals. At the end of the issue brief, we pose a set of questions that will guide our subsequent research into the value and feasibility of state postsecondary attainment goals.

We gratefully acknowledge the Joyce Foundation for supporting this issue brief.

The State of States’ Attainment Goals

In 2009, the Lumina Foundation launched an initiative to increase “the proportion of Americans with high quality degrees, certificates, and other credentials to 60 percent by 2025.”[1] This goal was based on workforce projections from the Georgetown Center for Education and the Workforce, and related efforts have been supported by numerous grant-making organizations – including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Helios Education Foundation, and Kresge Foundation – and intermediaries – including Complete College America and the Community College Research Center. Also in 2009, the Obama administration publicly called for an increase in the US college graduation rate and challenged higher education leaders to make the US, once again, the best-educated country in the world.[2]

To achieve these national aims, Lumina encouraged individual states to set their own attainment goals that aligned with the 60 percent national goal and to outline the strategies and policies needed to achieve those goals. By March 2018, 42 states had set attainment goals, and many of those states formulated strategic plans to achieve those goals.[3] As states’ current attainment rates vary, so do their goals. While some states have adopted Lumina’s national goal outright, others have customized their goals’ thresholds, target populations, and focus credentials.

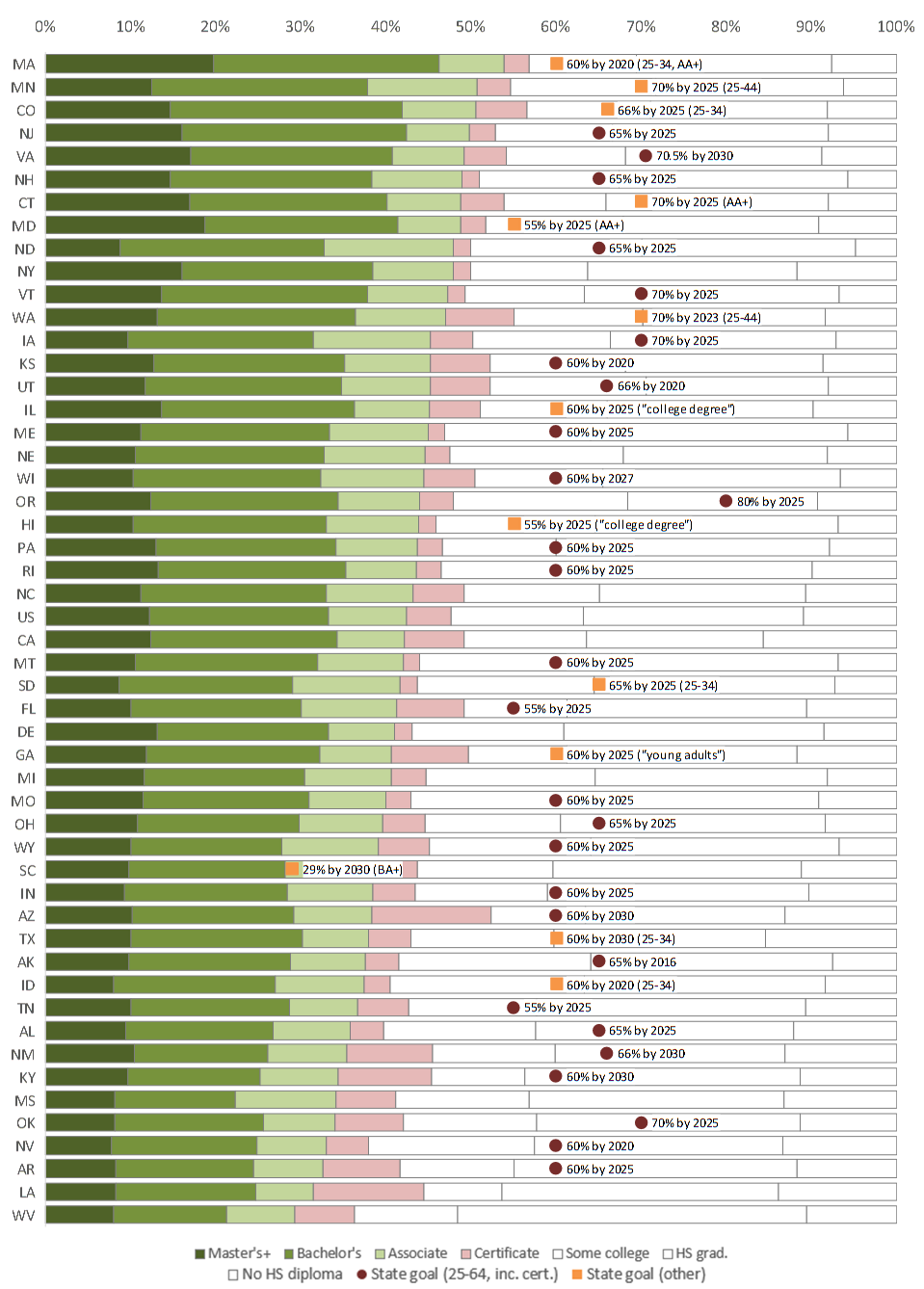

Figure 1, below, shows the variation in states’ current levels of attainment and their corresponding attainment goals.[4] Massachusetts and Colorado have the highest attainment rate when all postsecondary credentials are counted (including, bachelors, associates, and workforce-relevant certificates). States’ attainment levels are influenced by several factors, including the net migration patterns of educated persons, so states’ goals and approaches to increasing attainment levels naturally vary. As shown below, some states’ attainment goals are more ambitious than others – with Oregon’s attainment goal of 80 percent far exceeding other states. Goals indicated by a maroon circle are aligned to the Lumina national goal in terms of the age range (25-64) and set of credentials assessed (including certificates). Goals indicated by an orange square are either based on a different age range or are focused on a different set of credentials than the Lumina national goal (the population for these goals also differ from the population used for the attainment data in Figure 1). [5]

Figure 1: State-by-State Attainment Rates and Goals

While the Lumina Foundation and many other support organizations have coalesced states around a national attainment agenda, states themselves have social, political, and economic reasons to improve the educational outcomes of their residents. Recent research and news headlines have highlighted growing disparities in health, social, and economic outcomes along a range of personal characteristics like income, race, and geographic locale.[6],[7] These disparities are often compounded by a changing labor market that increasingly values a high-quality postsecondary credential. The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates roughly 40 percent of all US jobs will require some postsecondary training by 2024, and that jobs requiring a postsecondary credential will increase much faster than low-skill jobs.[8] Moreover, by 2020, an estimated 65 percent of job vacancies will require educational training beyond high school, suggesting that, over time, all US jobs will increasingly require postsecondary education. In 2017, however, only 43 percent of 25 to 64-year-olds have an associate degree or higher.[9] State policymakers have an economic imperative to respond to changes in the labor market by ensuring state residents have the skills and credentials necessary to get jobs, and that local and regional businesses have an adequate supply of qualified workers. Moreover, the approach must be holistic and focus on improving attainment rates of current undergraduates as well as adults without postsecondary training.

States also have a fiscal responsibility to ensure that they are maximizing their return on investment in postsecondary education and training and not wasting public resources through inefficiencies in the postsecondary pipeline. As of 2014, more than 31 million adults had enrolled in college but left without receiving a degree or certificate.[10],[11] As noted at a 2018 American Enterprise Initiative event, these inefficiencies limit students’ opportunity for higher wages and better employment outcomes, and “[create] large private and societal costs: for the individual, in the form of student debt and lost time and, for society, in forgone tax revenue and wasted public subsidies.”[12] Yet, striving for an attainment goal can increase these inefficiencies if states overly invest in postsecondary credentials with little long-term labor market value for prospective students. In fact, Maryland eschewed postsecondary certificates altogether and instead set a goal to increase associate and bachelor’s degree attainment rates to 55 percent by 2025. Governor Martin O’Malley justified this proposal by noting that high-skilled, high-wage jobs will only come to the state if there are sufficient numbers of highly educated workers available. His comments suggest that Maryland’s focus on associate and bachelor’s degrees, excluding certificates, is based on an estimate of what will be in the best economic interest of the state.[13]

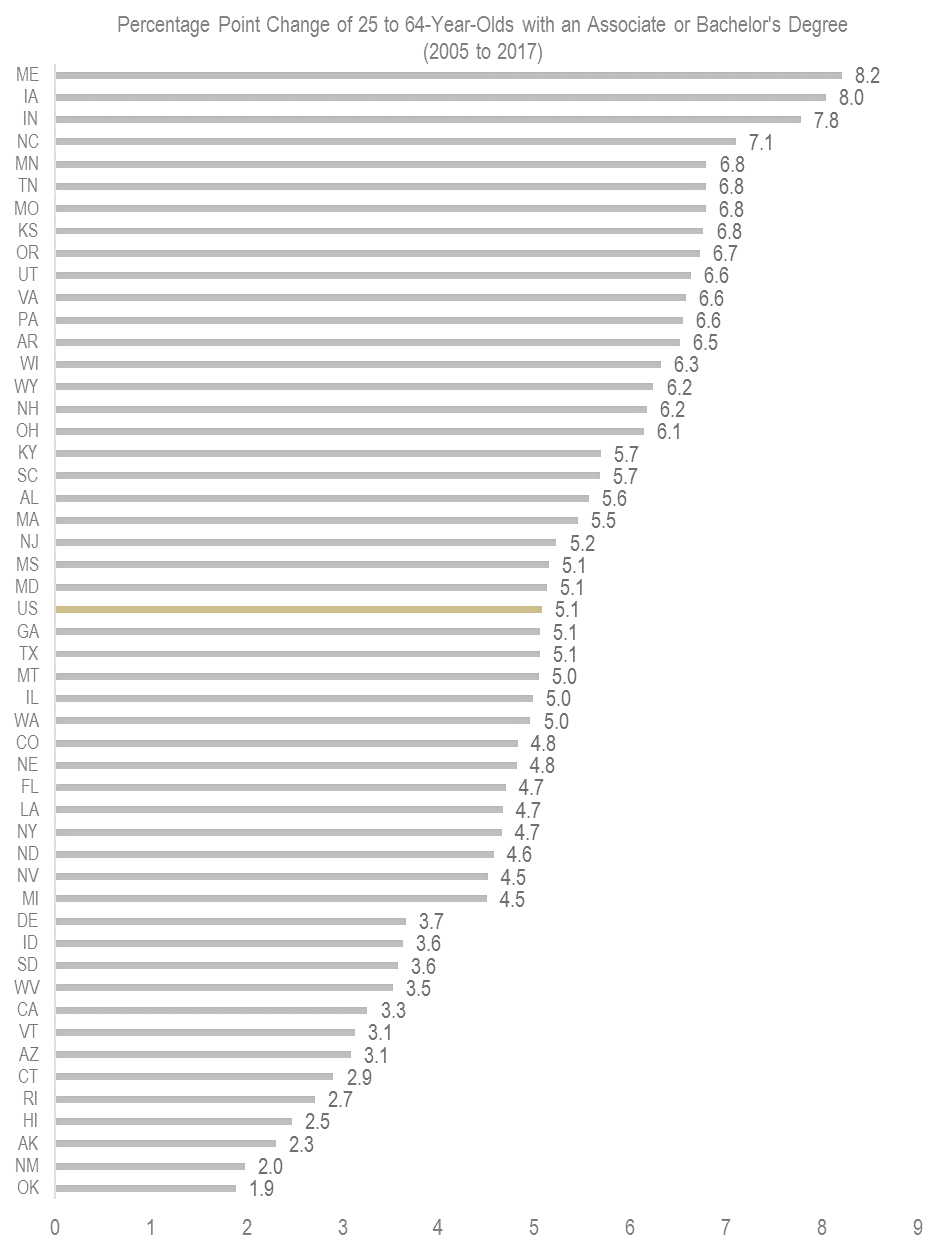

Figure 2 shows the changes in attainment rates – as measured by the share of the population aged 25-64 with an associate degree or higher – by state and nationally since 2005. [14] Nationally, between 2005 and 2017, the attainment rate increased by 5.1 percentage points. The potential impact on individuals and society of increasing attainment levels cannot be understated. Yet, determining whether changes in attainment are due to increased opportunity for state residents as a direct result of state interventions or due to external factors unrelated to state actions is difficult. For instance, through targeted investments in new interventions and initiatives, Indiana increased its associate and bachelor’s degree attainment rate by 7.8 percentage points between 2005 and 2017, exceeding the national average by more than 2 percentage points.[15] Yet, despite these investments, the attainment rate for younger residents has remained fairly flat because of population growth in that age group.[16] Instead, Indiana’s attainment rate growth appears to largely come from older residents who returned to college after the Great Recession limited their labor market opportunities. While attainment gains amongst adult students can have a significant personal, social, and economic impacts, the extent to which those gains are the result of state investments or exogenous factors is difficult to discern. Indiana’s attainment progress demonstrates how non-policy-related factors like economic conditions or net migration patterns may obscure the relationship between state policies and interventions and state attainment outcomes.[17]

Figure 2 – All states have seen improvement in their attainment rates since 2005, with Maine, Iowa, and Indiana showing the largest percentage point gains

The diversity and size of the typical attainment goal age cohort (e.g., 25-64) can also obscure real gains in attainment amongst more discrete age cohorts; moreover, investments targeted at improving college-going and college attainment for younger students alone will likely have a trivial impact on the attainment rate for the full attainment cohort overall. Thus, to meet their attainment goals, states must differentiate their attainment strategies to accommodate residents at all stages of the attainment age cohort, with significant investments in retraining older workers who need additional skills to thrive in the current labor market.

Despite a public focus on meeting attainment goals and the relative economic urgency of doing so, failing to meet attainment goals may have limited political ramifications for state executives. Regular electoral transitions in states’ executive offices may limit any existing political pressures – new governors can easily shift blame to their predecessors – although the economic pressures may persist. Further, attainment goals are inherently low-stakes since there are no explicit consequences attached to failing to meeting them. While these factors may undercut the overall motivation to achieve the goal, they may also decrease the perverse incentives and “gaming” that have plagued other goals-based efforts to improve public education. For example, No Child Left Behind has incentivized states to lower their academic standards while high-stakes testing, more generally, has resulted in “educational triage” practices where relatively high- and low-achieving students receive less attention. [18],[19] Higher stakes may incentivize states to engage in non-optimal behavior like increasing the provision and attainment of low-quality certificates rather than increasing access to and completion of associate or bachelor’s degree programs. At the same time, lower stakes may diminish the political will needed to make substantial progress. State executives and legislators, facing budgetary constraints, can disinvest in programs and services designed to increase attainment with few political ramifications.

Despite the complexities of measuring and sustaining progress, stakeholders in states with attainment goals say that the process of setting the goal and outlining the strategies to meet the goal are essential to align resources and mobilize various actors for change. The experiences of these stakeholders and the prevailing wisdom in change management point to a few key activities that are essential to realizing progress: [20],[21]

- Making the case for the importance of the attainment goal to various constituents through internal and external communications;

- Engaging key stakeholders in supporting and adjacent departments, divisions, and sectors;

- Developing a vision and comprehensive strategies to meet the goal;

- Identifying key interim milestones and regularly evaluating and reporting on progress to the goal.

Making the Case Through Internal and External Communications

A thoughtful and robust communications strategy is an essential tool to ensure buy-in from stakeholders, maintain accountability to the public, and develop and implement effective policies to achieve the postsecondary attainment goal. Pursuing an attainment goal requires collaboration across multiple state agencies and departments and achieving the goal requires public buy-in and participation. State governors and prominent advocacy organizations, therefore, must play a central role in keeping the public engaged in and informed about attainment goal efforts; similarly, state governors and senior administrators must also take an intentional approach to internal communications to the staff of the departments and divisions working on attainment-related policies and programs. These actions raise the visibility and importance of attainment efforts and can generate the accountability, political pressure, and political incentives needed to make meaningful progress.

State governors have employed numerous strategies to convey the importance and urgency of attainment goals to the broader public. Michigan’s new leader, Gretchen Whitmer, emphasized the importance of the state’s attainment goal – 60 percent by 2030 – during her primary and general election campaigns and then used her first “state of the state” address in January 2019 to present her plan for achieving the goal.[22],[23] Other governors have aligned attainment efforts to workforce development plans that stress the economic necessity of increasing the number of individuals with postsecondary credentials. In Alabama, Governor Kay Ivey and former Governor Robert Bentley incorporated both K-12 and higher education attainment goals into the AlabamaWorks! program, which strives to ensure “communities, business, and industry are supported in a collaborative process to build prosperity through the opportunity of meaningful work and a growing economy.”[24] Similarly, former Governor Mary Fallin of Oklahoma explicitly linked attainment goals with economic development and the growth of wealth for state residents.[25] Each of these strategies engages and activates voters and puts downward pressure on legislators to support and develop plans to achieve attainment goals.

While the governor often has the largest individual platform in the state, legislatures and advocacy organizations, working collectively, can effectively communicate the importance of an attainment goal to the public and thus create the internal pressure needed to elevate attainment efforts on state policy agendas.[26] For example, as of 2018, North Carolina was one of eight states without a postsecondary attainment goal. Over the last year, the legislature, across party lines, developed an external campaign underscoring the importance of increasing postsecondary attainment.[27] Similarly, advocacy organization, such as Complete College America, have engaged in public campaigns to build support from voters while also directly lobbying state governments and working to draft legislation that will advance attainment goals.[28] These groups advance their agendas through public reports, a robust media strategy, and by developing a deep working knowledge of state governments and their legislative processes.[29]

Engaging Key Stakeholders in Supporting and Adjacent Departments, Divisions, and Sectors

Increasing postsecondary attainment is not only the responsibility of a state’s colleges and universities; it also requires investments along the entire education and industry pipeline, from pre-kindergarten through college graduation and extending on to adults without postsecondary credentials. In fact, five of the 10 recommended strategies for increasing postsecondary attainment from the College Board’s National Commission on Access, Admissions, and Success in Higher Education were focused on improving PK-12 education.[30] And many states are extending these efforts to ensure students and adults can move seamlessly between postsecondary experiences and the labor market.

For example, New Mexico’s attainment goal explicitly sets targets for both K-12 and higher education. The state’s Route to 66 plan calls for 66 percent of working-age residents to earn a postsecondary credential by 2030. In order to achieve this goal, New Mexico is working to better align K-12 with higher education. As part of its Every Student Succeeds Acts (ESSA) plan, New Mexico set K-12 proficiency targets informed by college and career readiness standards so as to minimize the need for remediation in higher education, a major roadblock for students seeking to complete a postsecondary credential. In future years, the state plans to incorporate college enrollment rates as explicit features of its K-12 accountability framework and fund additional dual credit and Advanced Placement opportunities to smooth the transition between high school and college.[31] To develop these integrated strategies, the state legislature facilitated a series of convenings between state higher education, K-12, and workforce development officials in order to design plans that would improve pathways from high school, through college, to high-skill jobs.[32],[33] Additionally, state leaders engaged community members – including parents, teachers, and other state residents – in convenings to solicit input on plans to align educational systems and prepare students for postsecondary training and jobs of the future.[34] Engaging individuals across the K-12 and postsecondary sector facilitated the development of targeted state attainment goals and strategies to achieve these goals.

Attainment goals are intended to help states meet future labor market needs, making collaboration between higher education leaders and local industry leaders essential. As part of its Drive to 55 Alliance, Tennessee developed a cross-agency, public-private partnership co-chaired by Nissan and the Tennessee Chamber of Commerce and Industry, with members from over 50 employers and 12 public colleges or college systems. The Alliance enjoys the strong support of the governor and is a major focus for the state’s Board of Education.[35] Increasingly, employers are also partnering directly with post-secondary institutions – the partnership between Starbucks and Arizona State University as one of many recent examples – to provide educational opportunities and training for employees.[36] While these programs mostly exist between institutions and employers, there is potential for larger strategic partnerships between groups of employers and state public education systems. Such partnerships can help younger and older workers, alike, access and afford a quality credential and can help employers retain a more skilled workforce; at scale, these partnerships can help states realize the social, political, and economic benefits of increased educational attainment.

Developing a Coherent Vision and Comprehensive Strategies to Meet the Goal

The theory of action underlying an increase in postsecondary attainment is multifaceted and complex. To make progress to the attainment goal, programmatic and policy improvements must occur within the PK-12 and postsecondary education systems as well as in adjacent governmental departments and external industries. No single policy or program can be a panacea for low postsecondary attainment rates. Rather, states must take a comprehensive and strategic approach to making improvements throughout the entire pipeline from pre-K to career. For example, if high school students are unprepared for college, their ability to earn a credential will be limited.

Rhode Island’s plan to increase postsecondary attainment to 70 percent includes targeted and comprehensive strategies to close equity gaps throughout the entire K-12 and postsecondary pipeline. These strategies include reducing Advanced Placement test fees, providing free PSAT and SAT exams during high school, expanding dual and concurrent enrollment programs, reducing textbook costs with the Open Education Resources initiative, proposing the expansion of child care assistance for low-income students, and growing the youth talent pipeline through the Prepare RI initiative. Furthermore, the state introduced the RI Promise Scholarship at the Community College of Rhode Island, promising free tuition for all graduating high school seniors.[37]

In addition to efforts targeted at younger residents, Tennessee has explicitly targeted adult learners with its Tennessee Reconnect program which provides free tuition at public community or technical colleges for adults without an associate or bachelor’s degree.[38] The University of Memphis has taken a similar institution-level approach to enroll more adult learners in bachelor’s degree programs by offering scholarships, providing specialized advising to streamline the degree completion process, and offering credit for free online courses and corporate trainings these adults may have taken during their careers.[39] These programs targeting adult learners are important steps toward achieving “north star” attainment goals.

Identifying Priorities and Key Interim Milestones and Regularly Evaluating and Reporting on Progress to the Goal

In a crowded legislative agenda, attainment goals help legislators negotiate trade-offs when faced with competing legislative priorities and constrained budgets. Likewise, shorter-term, interim goals help maintain political motivation and focus on long-term attainment goals. Priorities and milestones are essential to holding leaders, agencies, and other stakeholders accountable for sustained and meaningful progress. They also create mechanisms to regularly evaluate and report on progress toward the attainment goal, which allows stakeholders to reconvene, assess, and adjust their approaches.

Maryland has a comprehensive strategy to meet its “north star” goal that includes interim goals for its university system and associated colleges and universities. As primary actors in meeting the postsecondary attainment goal, the University System of Maryland (USM), created a ten-year plan that included goals of increased enrollment to 174,000 students and higher retention rates across the system by 2018.[40] Interim goals were also set for individual USM campuses. For example, the Shady Grove and Hagerstown regional education centers have a goal to increase enrollment by roughly 2,000 students each by 2020. To meet these interim targets, system leaders planned to increase available courses and online offerings. But system leaders acknowledge that increasing enrollment is not sufficient, so they have coupled enrollment growth with augmented student supports in order to increase retention and graduation.[41] These tangible interim steps provide USM leaders the ability to explicitly track progress towards Maryland’s 55 percent attainment rate by 2025 as well as discrete checkpoints for policy reevaluation and strategic adjustments.

Conclusion and Remaining Questions

The motivations, implications, and approaches states are taking to set and achieve their postsecondary attainment goals vary widely. The extent to which these attainment goals will actually lead to substantive improvements in postsecondary attainment remains unclear, although some preliminary evidence suggests that many states may have difficulty meeting their goals.[42] In future analyses, Ithaka S+R will explore the policy and programmatic levers states have to accelerate their progress to more definitively understand the feasibility of meeting attainment goals and the investments that would be needed to do so.

As we outline in this paper, regardless of whether the goals are met, setting and working toward attainment goals may still be a worthy endeavor, and we can learn valuable lessons from the approaches of those states that have seen improvements in their outcomes. Below, we outline a set of key questions we intend to explore over the next several months. We believe the answers to these questions can yield valuable insights for higher education leaders, legislators, and policy-makers as they set their attainment policy priorities and evaluate the effectiveness of their attainment strategies.

- What levers can states pull to meet their attainment goals, how do these levers work together to increase attainment, and how do mitigating factors influence their progress and approach (e.g., changes in completion rate, increases in access, in-state migration, aging cohorts, etc.)?

- How have states like Maine, Iowa, Indiana, and others improved their attainment rates over the past decade?

- How do attainment goals themselves drive states’ behavior and are there risks or perverse incentives that can derail progress or inhibit opportunity?

- What role do state policymakers, institutional leaders, higher education coordinating and governing boards, and advocacy organizations play in designing the strategies to meet states’ attainment goals and how does the state governance and political context influence states’ approach and progress?

- What are the costs associated with increasing attainment, and what is the early evidence or predictions on the return on investment?

Read our interview with David Tandberg about these and other questions related to states’ attainment agendas at http://sr.ithaka.org/blog/an-interview-with-dr-david-tandberg.

Endnotes

- Lumina Foundation, “Equity Policy Academy: A Case Study,” accessed June 3, 2019, https://www.luminafoundation.org/files/resources/02-equity-policy-academy.pdf. ↑

- Andrew P. Kelly and Mark Schneider, eds., Getting to Graduation: The Completion Agenda in Higher Education (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2012). ↑

- Lumina Foundation, “Statewide Educational Attainment Goals: A Case Study,” accessed June 3, 2019, https://www.luminafoundation.org/files/resources/01-statewide-attainment-goals.pdf. ↑

- The data on certificates in Figure 1 are provided to the Lumina Foundation by Georgetown’s Center on Education and the Workforce (CEW). These data are estimates of the share of the population that holds a “high-value” certificate, where “high-value” denotes the certificate has economic value in the labor market. Due to the complexity of the estimation and the fuzziness of the data, these data should be interpreted with caution. ↑

- Source: Attainment from the 2017 ACS PUMS file, with the exception of certificates, which come from the Lumina Foundation and the Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce. State goals come from the Lumina Foundation and HCM Strategists. Massachusetts’ goal refers to “college degrees,” but is listed here as “AA+” for brevity. Louisiana reports that its goal is to “increase educational attainment of adult citizens (bachelor’s and associate degrees, and certificates and diplomas) to [Southern Regional Education Board] average by 2025.” California, Delaware, Michigan, Mississippi, Nebraska, New York, North Carolina, and West Virginia do not have attainment goals as of 2017. Figure excludes the District of Columbia. ↑

- Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, Chuck Collins, Josh Hoxie, and Emanuel Nieves, “The Road to Zero Wealth: How the Racial Wealth Divide is Hollowing Out America’s Middle Class,” Prosperity Now and Institute for Policy Studies, September 2017. ↑

- Alina Baciu, Yamrot Negussie, Amy Geller, James N. Weinstein, and National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, “The State of Health Disparities in the United States,” in Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity, National Academies Press (US), 2017. ↑

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, “The Economics Daily, 37 Percent of May 2016 Employment in Occupations Typically Requiring Postsecondary Education,” accessed June 3, 2019, https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2017/37-percent-of-may-2016-employment-in-occupations-typically-requiring-postsecondary-education.htm. ↑

- Anthony P. Carnevale, Nicole Smith, and Jeff Strohl, “Recovery: Job Growth and Education Requirements through 2020,” Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, 2013. ↑

- Doug Shapiro, Afet Dundar, Xin Yuan, Autumn T. Harrell, Justin C. Wild, and Mary B. Ziskin, “Some College, No Degree: A National View of Students with Some College Enrollment, but No Completion (Signature Report No. 7),” National Student Clearinghouse (2014). ↑

- Setting attainment goals to raise the overall educational level of a state’s population, and setting completion goals for enrolled students to receive a credential, are separate but related levers that are important for establishing a “north star” goal. ↑

- “Elevating College Completion: What Can Be Done to Raise Postsecondary Attainment in America?” American Enterprise Institute, accessed June 3, 2019, http://www.aei.org/events/elevating-college-completion-what-can-be-done-to-raise-postsecondary-attainment-in-america/. ↑

- University System of Maryland, “Increasing Educational Attainment in Maryland: A Discussion of Challenges and Issues Facing Maryland and the USM,” accessed June 3, 2019, http://www.usmd.edu/10yrplan/process/55educ.doc. ↑

- Source: American Community Survey Public Use Microdata Sample, accessed via IPUMS. Note: includes only associate and bachelor’s degrees in all years (and excludes workforce-relevant certificates). ↑

- Due to data availability and quality, we currently restrict our analyses of changes in attainment rates to associate and bachelor’s degrees and exclude Lumina and CEW’s estimates of “good” credentials. ↑

- J.K. Wall, “Indiana’s Higher Education Achievement Results Mixed,” Indiana Business Journal, March 21, 2015, https://www.ibj.com/articles/52350-indianas-higher-education-achievement-results-mixed. ↑

- There is some evidence that states are considering cross-state migration as either an intended outcome of their efforts (i.e., higher attainment levels attract industry that attracts highly-skilled workers) or as a specified strategy for meeting their attainment goal (i.e., models account for net migration patterns in determining strategy). Maryland Higher Education Commission, “Report on Best Practices and Annual Progress Toward the 55% Completion Goal,” accessed June 3, 2019, https://mhec.maryland.gov/publications/Documents/Research/AnnualReports/2018BestPractices.pdf. ↑

- James E. Ryan, “The Perverse Incentives of the No Child Left Behind Act” NYUL Rev 79 (2004): 932. ↑

- Jennifer Booher-Jennings, “Below the Bubble: ‘Educational Triage’ and the Texas Accountability System,” American Educational Research Journal 42, no. 2 (2005): 231-268. ↑

- Lumina Foundation, “Statewide Educational Attainment Goals: A Case Study,” accessed June 3, 2019, https://www.luminafoundation.org/files/resources/01-statewide-attainment-goals.pdf. ↑

- John P. Kotter, “Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail,” Harvard Business Review (1995): 59-67. ↑

- Chad Livengood, “Whitmer Economic Plan: $15-an-Hour Minimum Wage, Repealing Right-to-Work,” Crain’s Detroit Business, May 29, 2018, https://www.crainsdetroit.com/article/20180529/news/661976/whitmer-economic-plan-15-an-hour-minimum-wage-repealing-right-to-work. ↑

- Chad Livengood, “State of the State: Whitmer Calls for 60% Higher Ed Goal by 2030,” Crain’s Detroit Business, February 12, 2019, https://www.crainsdetroit.com/government/state-state-whitmer-calls-60-higher-ed-goal-2030. ↑

- Alabama Department of Commerce, “AlabamaWorks!” accessed on June 3, 2019, https://alabamaworks.com/about/. ↑

- Oklahoma Works, “Post-Secondary Educational Attainment,” accessed June 3, 2019, https://oklahomaworks.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2017-Oklahoma-Educational-Attainment-Study-Print-and-Release.pdf. ↑

- John W. Kingdon, Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies (Boston: Longman, 2011). ↑

- Patrick Sims and Javaid Siddiqi, “Reaching a Postsecondary Attainment Goal: A Multistate Overview,” accessed on June 3, 2019, https://www.myfuturenc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/InfoBrief-EdAttain-Sims.pdf. ↑

- Complete College America,“New Rules: Policies to Meet Attainment Goals and Close Equity Gaps,” accessed June 3, 2019, https://completecollege.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/New-Rules-2.0.pdf. ↑

- Erik C. Ness, “The Role of Information in the Policy Process: Implications for the Examination of Research Utilization in Higher Education Policy,” in Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research (New York: Springer, 2010), 1-49. ↑

- College Board, “Coming to Our Senses: Education and the American Future,” accessed June 3, 2019, https://secure-media.collegeboard.org/digitalServices/pdf/advocacy/admissions21century/coming-to-our-senses-college-board-2008.pdf. ↑

- Education Strategy Group, “Leveraging ESSA: States Leading on Alignment of K-12 and Higher Education,” accessed on June 3, 2019, http://higheredforhigherstandards.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/HEHS-ESSA-Round-1-Plans-06092017.pdf. ↑

- H.M. 45, First Sess. Of 2013 (New Mexico 2013), https://www.nmlegis.gov/Sessions/13%20Regular/memorials/house/HM045.pdf. ↑

- H.M. 14, First Sess. Of 2015 (New Mexico 2015), https://www.nmlegis.gov/Sessions/15%20Regular/memorials/house/HM014.pdf. ↑

- New Mexico Public Education Department. “New Mexico Rising: Engaging our Communities for Excellence in Education,” accessed June 3, 2019, https://webnew.ped.state.nm.us/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/NM-Rising-ESSA-Report.pdf. ↑

- Drive to 55 Alliance, “Drive to 55,” accessed on February 13, 2019, http://driveto55.org/. ↑

- Arizona State University. “Starbucks College Achievement Plan: Education Meets Opportunity,” accessed June 3, 2019, https://edplus.asu.edu/what-we-do/starbucks-college-achievement-plan. ↑

- RI Office of the Postsecondary Commissioner, “A Roadmap for Postsecondary Attainment in the Ocean State,” accessed June 3, 2019, https://www.riopc.edu/static/photos/2018/02/22/Higher_Rhode_Island_-_A_Roadmap_to_70_by_25.pdf. ↑

- Tennessee Reconnect, “Tennessee Reconnect,” accessed June 3, 2019, https://www.tnreconnect.gov/. ↑

- Goldie Blumenstyk, “Bringing Back Adult Students Takes More Than a Catchy Campaign,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, February 12, 2018, https://www.chronicle.com/article/Bringing-Back-Adult-Students/242526. ↑

- University System of Maryland, “Increasing Educational Attainment in Maryland: A Discussion of Challenges and Issues Facing Maryland and the USM,” accessed June 3, 2019, http://www.usmd.edu/10yrplan/process/55educ.doc. ↑

- University System of Maryland, “Powering Maryland Forward: USM’s 2020 Plan for More Degrees, A Stronger Innovation Economy, A Higher Quality of Life,” accessed June 3, 2019, http://www.usmd.edu/10yrplan/USM2020.pdf. ↑

- Lumina Foundation, “A Stronger Nation: Learning Beyond High School Builds American Talent,” accessed June 3, 2019, http://strongernation.luminafoundation.org/report/2019/#predictive. ↑