Stranded Credits: A Matter of Equity

Executive Summary

In this report, we review the results of an in-depth descriptive qualitative study that examined the lived experiences of students and staff familiar with institutional debt, also known as stranded credits. Our findings indicate the following:

- Stranded credits disproportionately affect students of color and those from low socioeconomic backgrounds

- Stranded credits impact students’ academic and career trajectories, can mean the difference between stopping out and dropping out, affect financial aid eligibility, and have a detrimental impact on students’ psychological well being

- Stranded credits prevent students from taking advantage of the financial and career opportunities that could help settle their institutional debt

- Institutional bureaucracy sometimes contributes to the accumulation of institutional debt, particularly for first generation students who are unfamiliar with how to navigate the collegiate environment

- Intersecting identities such as first generation and socioeconomic status can increase a student’s risk for accruing institutional debt

- Because there are restrictions on the use of federal aid and very few financing options, students usually have to settle their outstanding debt with personal funding

- Payment plans to settle institutional debt are not necessarily helpful for students who are experiencing financial instability

- Debt relief programs offer students an opportunity to address their institutional debt while also continuing their matriculation

- Institutions need to be more flexible and compassionate to help students resolve stranded credits. It is in their best interest to create solutions that will help keep students enrolled and to go on to be well-employed contributing alumni.

Introduction

Racial and ethnic demographics continue to shift in the United States, and more students of color, first-generation students, and students from lower-socioeconomic backgrounds pursue higher education. In some states, persons of color are quickly becoming the majority.[1] However, while this shift is occurring, certain groups are being left behind in higher education and workforce opportunities. The disparity among Black and Latinx persons—in particular in higher education and employment—continues to widen, making the scarcity of qualified workers for higher paying careers more pronounced.[2] In addition to the tremendous loss for the national workforce, the failure to recruit more minoritized persons in more specialized and higher paying fields reinforces a longstanding race and class divide in both labor and wealth, placing real economic limits on earning potential that has broader social implications for minoritized communities. Historically underrepresented students continue to bear the negative impact from the cumulative disadvantages associated with systemic inequity in education.[3] One of the most significant issues affecting the way students of color and from low-income backgrounds participate in higher education is rooted in the way systemic racism has shaped wealth gaps and student debt, including debt owed directly to institutions.

Student Debt

The earned-income potential for those who have bachelor and graduate degrees varies by socioeconomic status (SES), race, and gender;[4] however overall, obtaining a degree significantly increases lifetime earnings.[5] Recent data indicates that public four-year universities are becoming increasingly diverse;[6] with Black and Latinx students more likely to enroll in public institutions than private.[7] However, the increase in diversity is taking place at less well-resourced schools,[8] and students of color still encounter more barriers when it comes to earning a bachelor’s degree. Some of these barriers include financial stress, miscommunication and misalignment between students and faculty and advisors, a lack of mentorship and support, isolation, as well as racial and socioeconomic exclusion.[9] Consequently, there has been renewed attention to racial and socioeconomic equity aimed at improving access, matriculation, graduation, and job placement for minoritized and low-income students in higher education.

Student debt has risen to the top of the national agenda as one of America’s most pressing equity issues in higher education. Student debt has been linked to increased financial stress, attrition, and even mental health challenges such as depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation.[10] It is also widely recognized that student loan debt and the racial wealth gap reinforce each other.[11] While many students of all backgrounds are grappling with the weight of student debt, the data shows that minoritized students, first generation students, and students from low socioeconomic backgrounds are disproportionately affected negatively by student debt, as they hold higher cumulative balances and default at a higher rate.[12] Students of color are more likely to bear the more pervasive consequences of high student debt such as lower credit scores, limited ability to buy a car or house, and entering lower-paying, lower-skill jobs in order to repay the debt.

Stranded Credits and Equity

Usually when student debt is discussed and examined, the focus is on federal and private loans; however there are other more insidious forms of student debt that affect thousands of students each year and impact their ability to matriculate, transfer, qualify for scholarships and even qualify for job opportunities. Stranded credits is a phenomenon where students earn academic credits but cannot access them due to an unpaid balance with a previously attended institution that is holding their transcript as collateral. Until recently, there has been scant attention paid to stranded credits, but it is receiving more attention because of their negative impact on student matriculation, transfer, and job placement. Even worse, it has been shown that stranded credits have a disparate impact on minoritized students and students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.[13]

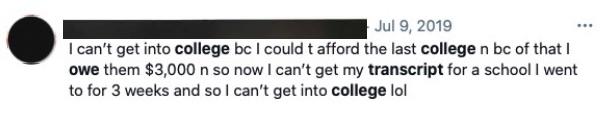

In fact, some experts identify stranded credits as a key component of the current student debt crisis facing American college students because institutional debt often goes unnoticed and unregulated.[14] This insidious form of debt affects millions of students and it accrues “because of the misalignment of two sets of rules for tuition payments that are owed when a student withdraws from classes early—the rules from the US Department of Education and rules from the colleges.”[15] In particular, when a recipient of Title IV aid withdraws from an institution during a payment period/period of enrollment, a calculation is made to determine how much of the funds must be returned.[16] This policy, known as the return of Title IV Funds or R2T4, often results in stranded credits because the institution often sends the financial aid awarded to the student back to the government as required, however the balance for the courses that were not completed results in an institutional balance on the student’s account. In some cases, this may even result in turning a Pell grant into a loan. Consequently, R2T4 cases disproportionately impact students from low-income backgrounds.[17] In addition to the mismatch between student loan dollars the federal government expects to be returned and the tuition dollars institutions expect to be paid, students with limited financial means also accrue other types of institutional debt including library fines, parking tickets, and other non-academic related expenses. All of this debt has to be paid out of pocket by the student and there are very few financial options for low-income students seeking to pay down this debt. This has become even more acute since the advent of the pandemic, sparking demands for policymakers to address the problem.[18]

The transfer process is another key area affected by stranded credits. Students of color and from low SES backgrounds often begin their higher education journey at community colleges and rely on transferring credits to a four-year institution in order to obtain a bachelor’s degree. Research on the lack of credit transferability between institutions is sparse, especially in regard to race, ethnicity, and income status. For example, in 2017, the United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) conducted an analysis to capture the loss of credits—as high as 43 percent overall—for those seeking transfer.[19] However, this report did not include student demographic data. The best example we could find was a study restricted to a sample of Hawaii and North Carolina students that showed White students had the lowest rate of transferable credit loss at 6.1 percent; meanwhile, Black and Asian students both had credit loss rates greater than 10 percent, and non-resident immigrant students lost 12 percent of their transferable credits.[20] It is no wonder then that the rate of degree completion for students of color and students from low SES backgrounds is markedly lower. The increased likelihood of students of color earning and paying for credits they are unable to utilize toward their degree furthers the gap and further contributes to disproportionate student loan debt.

Goals

This report builds upon our previous research on stranded credits by providing the results of a qualitative inquiry of the stranded credit phenomenon and how it affects students of color and those from low socioeconomic backgrounds.[21] Our previous report highlighted statistical data that showed the pervasiveness of stranded credits, its cost, and the type of students who are disproportionately affected by it. In this report, our findings will highlight the student perspective to give more insight into how institutional debt perpetuates and exacerbates inequity in higher education. We spoke to both students and a few staff members about their experiences and perspectives on stranded credits. A summary of participants’ roles and affiliations is included in Table 1. The overarching goal of this study was to glean new insight into how stranded credits may affect student matriculation through college and beyond. Towards this end, this study had four objectives: 1) To gather student understanding and perspectives about stranded credits; 2) To understand how stranded credits have shaped different student experiences of higher education and their matriculation towards a degree; 3) To understand how campus administrators and staff perceive the phenomena of stranded credits, how their institutions handle stranded credits, and what they think should be done to address the issue; and 4) to identify the ways in which stranded credits shape equity outcomes in higher education. To address these objectives, we posed the following research questions:

- What experiences do students and administrators have with stranded credits?

- How do stranded credits shape the way students of color matriculate through higher education and beyond?

- What are some proposed alternatives to stranded credits?

Methodology

We used interviews and focus groups to understand student and administrator experiences with stranded credits and triangulated our findings by collecting social media posts. A more in-depth description of our methodology, particularly of our data analysis, is included in Appendix I. For our sample we reached out en masse to students and staff who may have experience and knowledge of stranded credits. In particular, we targeted institutions that had created debt relief programs that are designed to help students settle institutional debt so they can re-enroll and continue their education. We interviewed 13 students and staff from five different institutions. Most of our student participants (see Table 1 below) were in an institutional sponsored debt relief program designed specifically to address stranded credits so that students could re-enroll and continue their education.

Table 1: Participants

| Name[22] | Role | Institution/Type | Stranded Credits Debt Relief Program |

| Tina | Student | Midwestern-public research university | yes |

| Jan | Transfer counselor | Northeast-public four-year college | no |

| Samantha | Student | Midwestern-public research university | yes |

| Angela | Student | Midwestern-public research university | yes |

| Dereck | Student | Midwestern-public research university | yes |

| Kasey | Student | Historical University-public HBCU research university | no |

| Dawn | Student | Eastern-private research university | yes |

| Rhonda | Student | Midwestern-public research university | yes |

| Brittany | Transfer counselor | Northern community college | yes |

| Jake | Student | Midwestern-public research university | yes |

| Shonda | Student | Midwestern-public research university | yes |

| Amy | Student | Midwestern-public research university | yes |

| Aisha | Student | Midwestern-public research university | yes |

Findings

Our findings reveal that stranded credits have significant and long reaching impacts on the way students navigate through higher education, in many cases delaying, altering, or completely halting their plans. Below, we highlight the predominant themes that emerged from our analysis.

Types of Students Affected

Despite casting a wide net, all of the student participants who volunteered for this study were students of color, and an overwhelming percentage presented as women (we only had two participants that presented as male). Participants described the negative impact stranded credits had on themselves as well as other students of color they knew. As one student, Aisha, explained, “It’s very frustrating, the way they use balances as leverage over your transcript….because you look at it like who is carrying that on? I’m pretty sure it’s marginalized students who are most affected by it.”

Not all of our participants necessarily agreed that stranded credits disproportionately affected students of color. One of the transfer counselors we interviewed, Jan, who identifies as a white woman, expressed that “…it can happen to anyone. I think that any student can find themselves in that position. It does reflect more back on students that have less resources but even though a student has a resource at one time, that can disappear at any point.” However, several of our participants spoke about how stranded credits negatively affected students from lower socioeconomic groups, in particular, perpetuating a class cycle that made it more difficult to matriculate. As Kasey, who identifies as Afro-Latina and a Pell grant recipient, explained:

It doesn’t affect students who are at the top of the socioeconomic strata…They don’t have a reason to think about it or worry about it, but students who are in the middle or at the bottom of those strata—it pushes you down even further. Because what happens, what happened to me is that once I left [the university] I just didn’t see another way out. If I wanted advancement, I had to find a way to earn that bachelor’s degree, so I was going to do what it takes in order to get it. But being in the world of work when you don’t have a degree and you are undereducated, that puts you right on the same level socioeconomically as students and people who don’t have a degree at all or who have a high school diploma.

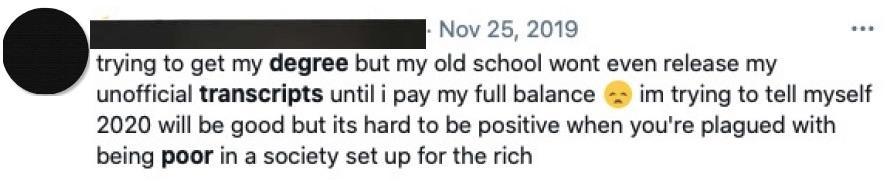

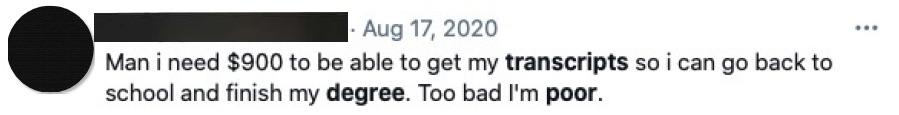

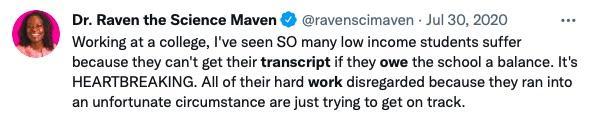

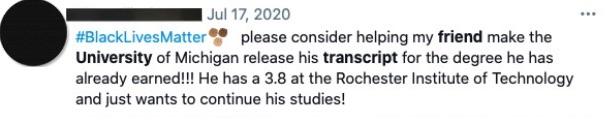

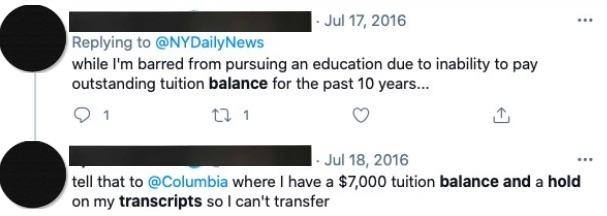

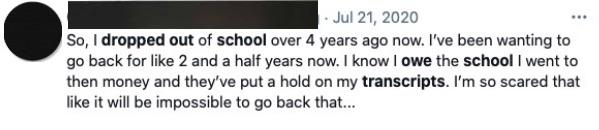

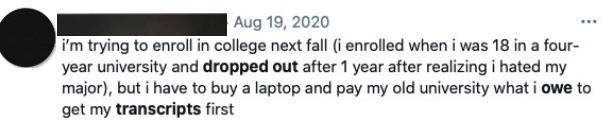

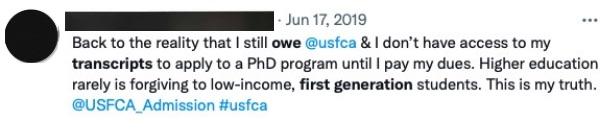

This sentiment about stranded credits locking students from low socioeconomic backgrounds into poverty was reflected across several student interviews as well as our collection of posts from social media.

While being poor may be one of the primary factors that place students at risk of experiencing stranded credits, we dug deeper to try to ascertain what conditions and events were typical among students who found themselves with institutional debt.

Typical Stranded Credit Scenarios

All of our student participants shared different stories about the circumstances that led to their experience of stranded credits, however they all shared one commonality—their collegiate journey began several years ago. When asked about their experiences with stranded credits, most of our participants’ stories began over five years ago, but some, such as Amy, who identifies as Black, went as far back as ten years to describe their experience:

…I was enrolled in the ‘80s and in ‘88 I had to leave because I was working two part time jobs and carrying a full load of classes and it was just too much. So I left [the university] and I wanted to get back into [my previous institution] and when Financial Aid contacted me after I enrolled like, it was two weeks before classes were supposed to start, and said that I owed from my previous attendance, that I owed X amount of money and I didn’t have that money, I couldn’t do it.

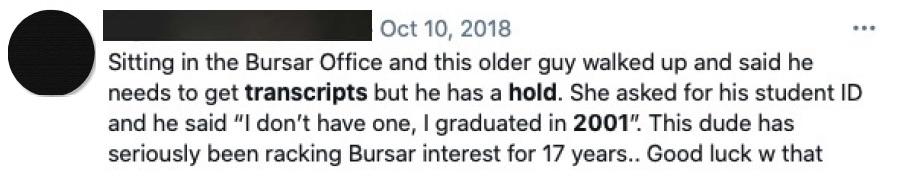

Our participants recounted experiences of starting school anywhere from the late 80’s to the early 2000’s. We found even more evidence of this kind of markedly dated start in the stories about students’ experiences with stranded credits.

With so many years between attending the first institution and their current institution, it seems reasonable to question whether the gaps between attendance contributed to losing track of or lack of urgency to pay off balances that would prevent the release of transcripts or a degree, but that is not the case. Our participants were quick to point out that the length of their academic trajectory was not due to a lack of desire, commitment, or effort to continue their education, rather it was a symptom of stranded credits blocking or derailing their matriculation toward a degree.

It may be obvious, but our student participants also shared the inability to settle institutional debt so they could resolve their stranded credits. They described their institutional debt as substantial enough that it was impossible to pay down on their own. The circumstances surrounding each participant’s accumulation of institutional debt differed. Some of our participants, such as Tina, described her poor performance as a contributing factor, stating that “third year was where I pretty much failed all of my courses; it left me with a balance of about $3,000.” A few of our participants, like Shonda, who identifies as Black, had to leave college because they did not have the financial resources to continue, only to discover later that their financial difficulties were compounded by additional institutional debt. As she explained:

I needed money and I worked more than the 20 hours I was supposed to work under work study. Well, when you do that, the system at the time recognized that you are working too much, and it revoked all of my loans for that year. Right, so I technically got kicked out of [the university] because I owed them money that I did not have, money to pay for school. So that was the downfall and that started in December of 2001 and the economy was sketchy then and then it just got rough.

Dawn, who identifies as Black, describes how the circumstances that led to her institutional debt were related to personal life events:

To give you a little more context as to why this happened to me, I got divorced; I was in a really bad marriage. Because of the divorce and the situation, I don’t want to go into too much detail, I only had one stream of income and I had two small children to care for.

Several students described similar dramatic life events (divorce, pregnancy, loss of a job) that triggered financial instability, only to be exacerbated by institutional debt. However, despite their proximity to institutional debt, none of our participants had heard of the term “stranded credits” until we approached them for this study. Rhonda, who identifies as Black, explained, “I know it’s probably happening to a lot of people, but I think it’s just not known as Stranded Credits.” Nevertheless, participants were familiar with the situation of earning credits that were being withheld due to institutional debts owed because of unpaid tuition or student fees. In fact, almost half of our student participants either had family or friends with stranded credits. Below Kasey describes how stranded credits affected her friend:

A friend of mine who actually moved to Canada said, ‘I don’t have the thousands of dollars I need to enroll in your university so can I at least have my transcript so that I can go to another university somewhere and enroll somewhere?’ And, once again, her transcript was held hostage. And because she knew me she tried to work that angle to see if I could work out some type of arrangement and it’s like this is a standard rule. Like, I can’t do anything, this is it.

Another participant, Jake, who identifies as Black, describes how stranded credits affect another member of his family: “[It] happened with my mom. She went to [a university] and it took her years to pay off Ferris before she could finish up her degree.” And Amy describes how it affects more than one person in her family:

I think it’s pretty widespread. I mean it affects most of the adults in my household. My husband owes [the university] too and my sister’s the same way, she tried to go back and ended up being able to pay off her balance the first time she went back. But then the second time she went back she was married, had children and she couldn’t afford to get back, so her credits are still just out there.

Our collection of social media posts produced several examples of how stranded credits affected friends and family members, one going as far as to raise money for their loved ones so that they could pay off institutional debt.

These are only a few examples of the many we collected. These accounts underscore the disparate impact stranded credits have on the most under-resourced students. The particular ways institutional debt impacts students are as varied as the circumstances that led to their debt.

Impacts of Stranded Credits on Students

Our findings reveal various ways stranded credits affect students both while they are on the pathway towards a degree but also outside of their collegiate journey. The most prominent areas in which stranded credits appear to affect students are: 1) the trajectory towards a college degree; 2) career goals and planning; 3) ability to secure financial aid; 4) their psychological well-being.

Trajectory Towards a College Degree. Several of our participants described how stranded credits either placed a significant pause or completely halted their matriculation. Even when students planned to discontinue a particular academic track or transfer to another institution, stranded credits followed them, inhibiting their ability to pursue a different major or enroll in a different college. Samantha, who identifies as Black, describes how stranded credits completely halted her progress:

It would have been easier maybe to just go to a community college and finish or maybe until I got the money to go back to the university. But it was very frustrating, and it made me not be able to pursue my degree any further so it kind of stopped me in my tracks in a sense and I would have finished a long time ago if it wasn’t for that balance.

Rhonda’s experience with stranded credits highlights how even low levels of institutional debt can hold a student in limbo until they can pay the debt:

There was a hold on my transcript because I owed like, I want to say, maybe $400 or $500 to the university just for a failed course and so essentially they said that I had to pay the money back before they could transfer my credit and that meant that I had to sit out another semester because I couldn’t even enroll in a community college and bring my other credits that I earned from it because of the $400.

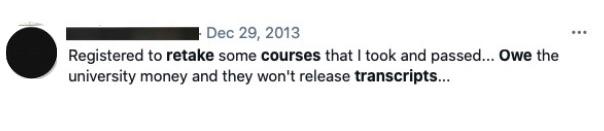

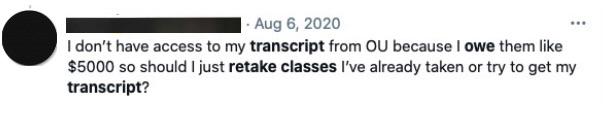

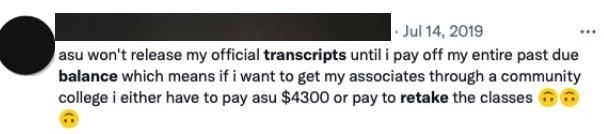

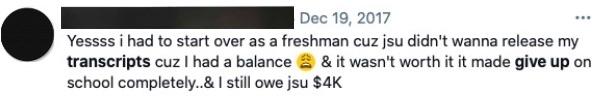

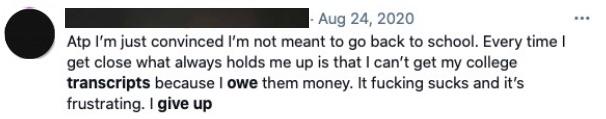

We found many examples online of students describing similar experiences of being “stuck,” unable to enroll, transfer, or progress because of stranded credits.

A few participants we interviewed said stranded credits changed how they progressed through their program. For example, Aisha, who identifies as Black, described how she couldn’t register for a particular class that fit with her schedule which in turn forced her to alter her work schedule, making it more difficult to juggle both school and work. Without the ability to transfer or even access the credits already, some students had to start over or retake classes they have already completed. Brittany, one transfer counselor we spoke to, explained her experience with this phenomenon:

We had a young man, both my colleague and I worked with him, and he ended up at another school here…. and they were the only ones that we could find that were not going to ask him to get the other transcript and he literally retook everything at our school. He got an associate degree and definitely had credit at another school.

Student participant, Tina, who identifies as Black, described how she earned enough credits to receive her degree, but because of the time gap between her original enrollment and her attempt to pay off her institutional debt, some of the credits were no longer considered valid:

I remember going in and I’m looking at the things I took, and they were like ‘some things were outdated,’ not outdated but they were like ‘oh there is a statute of limitation on this’, and I was like, I’m not taking that over again, I’m all the way over here now and I just gave up on it and I’m like fine I’ll just have a bachelor’s degree and that’s it.

We found similar examples online of students either contemplating or needing to retake courses due to institutional debt.

Our participants provided several reasons for why they had to leave their original institution, including failing out, the presentation of a job opportunity, switching career paths, and an unexpected life event like a pregnancy or financial difficulties related to paying tuition. In some instances leaving school meant dropping out for the foreseeable future to pursue something else, while in other cases, students expressed they simply wanted to “pause” or “shift gears” but always intended to return to finish their degree.

Stopping out vs. dropping out. For some students, the difference between dropping out of an institution and stopping out could be attributed to the ability to settle their debts with the institution. Some of our participants described stranded credits as a minor set-back, but most of our participants described how it forced them to completely stop their progression towards the degree they were seeking. Many of them described dropping out of school and pursuing other interests or trying to find a job that did not require them to have a degree. Angela’s story about her stranded credits is an example of this:

In 2008 I was like four credits shy of finishing. It was just with a Spanish class and having that account balance, and the economy was terrible in 2008 and so I needed to work. And I found a job…I’m like the district athletic director now and I did that without even finishing…

In Angela’s case, stranded credits completely blocked plans to continue with her education. She was fortunate to find employment without a degree, but it is not clear what potential opportunities she missed because of it. We also found many examples of how stranded credits can completely derail college matriculation on social media.

One of our student participants, Rhonda, explained how stranded credits are the tipping point, discouraging students who can be already struggling and have negative experiences with school:

It’s very discouraging in a way and I feel like when people make an attempt to say ’I’m going to go back to school, and this is what I’m going to do. I’m going to finish this.’ And then they go and make the inquiries about re-enrolling and then they get hit with that roadblock sometimes like that’s just it. They are like ‘OK cool, then I’m never going back.’

The students and staff we spoke to informed us that they think there are many more students burdened with stranded credits than public attention to the issue suggests, and that the impact of stranded credits extends beyond college.

Impact on Career Goals and Planning. Stranded credits impacted some participants’ career goals and planning, either making them change majors and career paths or altering their timeline for pursuing a particular career path. Jake describes how his original career path shifted as a result of stranded credits:

I changed majors and over the course of what it’s been basically twenty years, I don’t have any more money to go to school with. My company will pay but that means I have to pay off my balance at [the university] and get those credits sent over. Luckily, I’m in good standing with [my current institution] and I have a good job, so until I can get those credits, pursuing my original career goal isn’t a priority right now.

For some participants, stranded credits complicated or blocked career opportunities. This was the experience of Derek:

I have been passed over for several job opportunities simply because I did not have an undergraduate degree, even though I do have the business acumen and experience. It’s just that it’s something that has held me back from achieving and applying for positions that I am definitely qualified for, based on my experience.

Aisha described how stranded credits limited her ability to be promoted:

Ideally I could have moved up much faster somewhere else if I had had that physical paper in my hand. I know I can’t move because other people are going to require me to have it right up front. So to kind of build in that relationship with one company but know that you are really worth quite a bit more but being stuck because of the missing transcript.

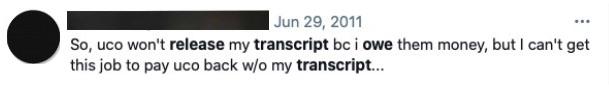

Both Derek and Aisha identify as Black and like many of their peers in the study, they expressed how they felt stranded credits locked them into a career pathway with limited promotion and earning potential, keeping them at a low socioeconomic level. This was echoed in the social media data we collected as well. In the following example, a student explains how she feels stuck in her earning potential (and ability to pay her institutional debt):

Amy explained this dilemma in the following way:

It puts you, for a student on the lower end of the economic ladder, it puts you in a box. Like, you can’t enroll in the new university, the old university won’t let you go because you owe them money. You can’t get the information that you need in order to go anywhere…you need a transcript in order to enroll. So you’re, it’s literally a four-square box. You can’t go anywhere.

Amy’s quote underscores the disparate impact institutional debt has on the most vulnerable and under-resourced, but also exposes the limitations and challenges of financial aid towards addressing this issue.

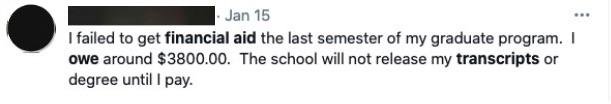

Impact on Financial Aid. Many of our students described how institutional debt crippled their ability to apply for needed financial aid, especially scholarships.[23] The irony of this is that their debt was often the result of insufficient financial aid that did not cover all of their educational expenses. This was the experience of Samantha, who had to stop out as a result of stranded credits:

With me being a single mom of course I was able to get Pell grants and more money so money didn’t really have to come out of my pocket for the [tuition]. But then after so long the money started to get less and less and not even just with school but with home, and I ended up having to go back to work. And then I wasn’t getting as much money to go to school because I wasn’t full time anymore. I tried one class, I said OK I’m going to try, and it was like $2400 for one class. It was a statistics class, and I did it and I wasn’t able to financially pay for it when I was done like I thought I was going to be able to because I was just getting back into the workforce and that’s how I ended up stopping.

Aisha described how limits on her student loans prevented her from paying for credits, which prevents her from transferring so she can finish the degree:

It’s just frustrating that I’m so close but I can’t finish because I owe. They said you maxed out your loans now because you went to school before so now you’ve got to pay out of pocket or find some grant or funds elsewhere. I wish I could have just taken the credits I had and gone to another school and just finished.

Jake offered a similar example about how stranded credits severely undermined his ability to use financial aid at all:

I maxed out my loan amount that I can get, so that if I want to finish up I have to either pay out of my pocket or get a personal loan. That’s why I haven’t yet. I don’t have any more money to go to school with. My company will pay but that means I have to pay off my balance at [my previous institution] and get those credits sent over.

These cases underscore the way students from low-income socioeconomic backgrounds rely on financial aid and how that reliance can also impede their ability to pay institutional debt so they can matriculate.

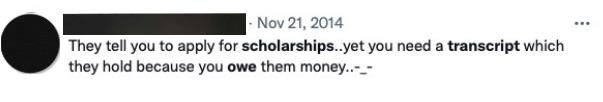

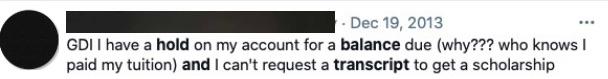

Beyond grants and loans, we also found examples of how stranded credits can inhibit a student’s ability to apply for other types of financial assistance such as scholarships. For example, one of our participants, Terri, described how she tried to apply for a scholarship, but couldn’t access the official transcript and had to resort to using an old unofficial copy she had on hand. The following examples from online users highlight this same struggle.

Psychological Well-Being. Not being able to matriculate, transfer, qualify for a job, or take advantage of other opportunities had deleterious impact on students’ mental well-being and emerged as a common theme in both our interviews and in the data we collected from social media. Our participants described how the challenges created by institutional debt affected their self-efficacy in their major and/or completing a degree and their hope for a different future where they had higher earning potential. Participant Shonda described her experience with stranded credits as trauma:

It’s funny because it’s something I forgot about in this experience. It’s probably tucked away as a trauma, and one of the reasons is because when I first was trying to go back to [school] earlier I wanted to bring as many credits as I could to bring over…

We found several examples of students expressing how stranded credits took an emotional toll on them.[24] Students posted messages recounting how stranded credits and their inability to access their transcripts and degrees resulted in severe anxiety, depression, and even thoughts of taking their life.

Navigating the System

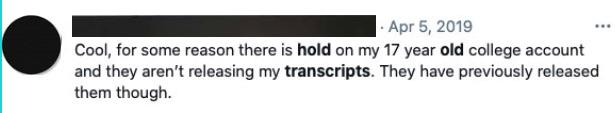

The burden of institutional debt appears to be closely related to difficulty students have with navigating institutional bureaucracy, particularly when it comes to the registrar and financial aid office. Our participants described how technical errors created situations that either led to stranded credits, exacerbated their struggle with stranded credits, and even mistakenly identified institutional debt that had actually already been paid. Derek described how an institutional error became entangled in his experience of stranded credits:

I checked [with the registrar] on a whim and they said [the balance I owe] are for classes I had taken in 2018 and even though I tried to resolve it for all of this time they were still telling me no. The balance is still lingering there, and it wasn’t because I didn’t do something on my end. It was Financial Aid dragging the process along and then continuing to play it off because what they had going on wasn’t streamlined enough where my Financial Aid file was lost in the grant scheme.

This example raises an important question in regard to the structure of institutional bureaucracy and whether efforts to create seamless processes, such as ‘one-stop-shops’ that centralize the location of financial aid, the bursar, and registrar office, are more effective in addressing and mitigating cases of stranded credits.

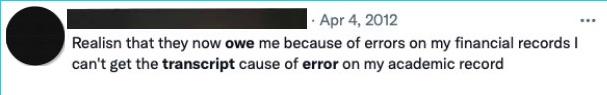

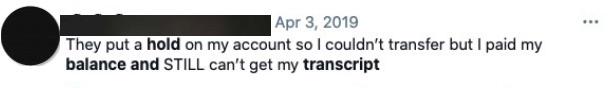

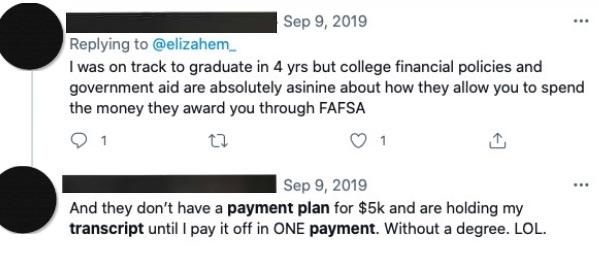

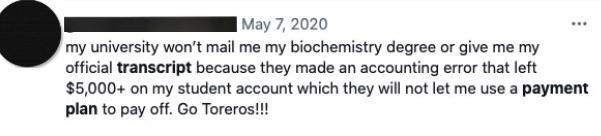

We found several examples where students cited institutional error in claiming they had stranded credits when they did not.

It was also pointed out how institutional debt increases the longer it goes unpaid. As transfer counselor Jan explained:

It’s compounding. Once you start adding interest to that…You know once you start putting costs onto that, you know you could take $200… Everybody knows that if you don’t pay a credit card bill you could get screamed at with just the interest rates and what happens to you and with the higher education nonprofits…

Some of the bureaucratic challenges were not due to institutional error, but a lack of awareness of how the bureaucracies of institutions of higher education work. Students described how unfamiliarity with the college environment could easily lead students into situations where they may unwittingly accrue institutional debt. Rhonda describes how her friend’s background as a first-generation college student led to stranded credits:

She didn’t have the knowledge to navigate all these systems. She didn’t know how to navigate financial aid; she went on a full ride scholarship. So all she did was basically put her name on the bottom line of a piece of paper and she went to school you know… [the institution] wasn’t helpful. They weren’t good with guidance at that time.

We found other examples of first-generation students struggling with navigating the collegiate environment and accruing institutional debt in the process.

For some students, a lack of awareness about how to navigate college coupled with financial aid limitations could lead to stranded credits. Many of the examples we shared previously about student trajectory and financial aid highlight how multiple variables can intersect to increase a student’s risk for stranded credits. To further complicate the matter, when students attempt to transfer, they also face the burden of dealing with the bureaucracy at two or more institutions. Trying to get a transcript released from one institution while trying to navigate the transfer process at another can be difficult especially if the institutions provide different or conflicting information and requirements.

Who Should Be Responsible for Settling Institutional Debt?

While the majority of our participants expressed that they felt holding transcripts for institutional debt was wrong, most of them also expressed that students have a responsibility to pay the debt eventually. Many of our participants emphasized that they were not asking for the institution to simply forgive the debt, rather, they wanted the institution to be more understanding and provide different avenues for settling the debt while they continued to matriculate. Some participants described how they sought out other remedies but found their institutions uncooperative or unresponsive. This was the experience of Dawn:

From 2017 until 2020 I was attending the university and I was told that until I fulfilled this balance, that I would not be able to enroll in classes and I could not get a copy of my transcript. And I tried several things to overcome that and to get back in school. I even went as far as writing a long-detailed letter to the dean of the program stating what my hardships were, why I wasn’t able to pay, what kind of education I received in-between that time and I never even received a response.

Transfer counselor Jan found the lack of institutional effort to come with alternative solutions hypocritical, “It’s just really interesting now higher ed, sometimes I think we present ourselves as opening doors when in fact we do but we open them a crack and we put like a doorstop in there.”

Many participants felt that preventing students from enrolling or transferring also limited student opportunities for jobs that would enable them to repay the debt. As Rhonda explained:

Before I could pay off the fees at both universities and then I could eventually enroll and finish one year, one year left in my undergraduate after this happened. They offer payment plans, but if you’re, you know, poor is poor…and you know when you are working trying to pay rent and trying to fulfill your basic needs and what you are earning doesn’t cover your basic needs. A payment plan is not helping.

Rhonda pointed out how limited payment plans are for addressing stranded credits for students from low socioeconomic backgrounds.

Because when you have debt like most people know OK, I owe this, and I want to pay it and what options do I have as far as payment plans and is there any assistance for me if I’m on a lower income? I just think the school needs to advocate for that.

While payment plans may not work for everyone, some students sought out opportunities to establish one, but ran into strict parameters or additional fees for setting one up or institutions that were unwilling to negotiate.

Student participants affiliated with a debt relief program expressed gratitude for the programs for helping them resolve stranded credits and for helping them to continue their education as Dereck describes below:

I went and talked to the counselor and that’s when she told me about the [debt relief program]. It’s what made me decide to come back. Actually, I’m a senior and I’m in my last semester, I graduate in May. Actually, May the Fifth is when I graduate so it’s been a long, long road.

The programs the students participate in use incremental payment plans to help settle debt. As Rhonda explained:

If you have a negative balance that you owe they are willing to pay off a portion of it as you complete your degree. If I enroll in a semester and I complete that semester successfully, then they pay half of that $1500. And if I move forward with my last semester and I complete those courses successfully then they pay the rest of the $1500. So they are paying incremental payments as you complete requirements, which I think is fair.

While programs like the one Rhonda refers to were credited for helping our students continue their education, the incremental payment approach still relies on students paying out of pocket funds up front to address their outstanding debt. This could pose a barrier for students who have substantial outstanding debt. All of our participants, both students and staff members, found the lack of options available to students for settling their institutional debt frustrating and unreasonable. Many offered some alternative suggestions for addressing stranded credits.

Policy Proposals for Addressing Stranded Credits

A few of our student participants, like Angela, did not have any policy proposals for addressing stranded credits because they felt that once students earned their credits, they should be granted the right to keep them. As she explained, “I don’t feel like they have the right to hold it. I understand they need to be paid but at the same time if you earned it and if you have a passing grade it’s yours, period.” However, many of our participants offered suggestions for how students could settle institutional debt that would not disrupt matriculation.

Ironically, even though many of our participants were affiliated with and credited an institutional debt relief program for helping them to address outstanding debt, none of them identified this kind of program as a policy proposal for addressing stranded credits. However, all of the students associated with the debt relief program expressed gratitude for the program and credited it with allowing them to continue their education. One important aspect that should be noted is that our student participants emphasized the way their debt relief programs made a broad, concerted effort to reach out to them, even when they were not enrolled. Students described receiving information from advisors as well as phone calls, emails, and letters from the debt relief program and expressed that the consistent outreach convinced them to give the program a try.

Overall, our participants also shared the sentiment that institutions need to be more lenient, flexible, and trust that students will make a good faith effort towards setting their balance once they are capable of doing so. As Amy explained:

I just think that they should have policies in place as it pertains to college with the student in mind and not with their profit and their pockets in mind first, not just with your mouth but with your actions saying that we are putting the student first.

Most of the policies proposed by our participants were vague when it came to details about policy alternatives, but some of our participants had very firm ideas about how institutions could help students address stranded credits. Kasey, for example, offered the following policy suggestion:

Perhaps, you know, if a college or a university made paying back fees or whatever monies that they owe mandatory after the students actually graduate and had their diploma in hand…maybe that could be worked out, you know, withholding perhaps the actual diploma but making transcripts available so that the student can go on, get some type of well-paying job and then put all of that back on the table.

Jan, a transfer counselor, also had firm ideas about how institutions can address institutional debt:

I think first off I think institutions shouldn’t be imposing fees beyond, like for example, if you don’t pay for a $200 graduation fee. That’s kind of ridiculous for a lot of students. That should be something like a box they can check. I’m attending graduation therefore I need to pay the fee.

Transfer counselor Brittany also felt that there should be leniency for low balances, but was more ambivalent about how institutions should handle higher institutional debt.

I definitely don’t think they should be held for a library book or a parking ticket. Now, when someone leaves $3000 or $18000 I don’t know what to think about that to be honest because I got to go to college because of student loans, right?

Although our participants struggled with how institutions should address student institutional debt in a way that was fair and supportive to student needs, they did express hope that the increased scrutiny would lead to change. Kasey told us that she hoped that our research would be used to warn college students who are not informed about how the system works. As she explained:

I never understood the consequences of not being able to pay back the money. I never understood the socioeconomic impact of not being able to finish college. And the system is not going to explain it to you. I think that these types of situations should be written up as case studies and studied in courses, should be explained to students from financial aid officials who are helping students onboard in college to get them enrolled, and should be reviewed with students even before they graduate.

Jan said that she felt that because of research like ours and recent press scrutiny, she feels a change is on the horizon and discussed a recent bill proposed by Representative Harriet Chandler that would allow students with stranded credits to access their transcripts.[25] Similar bills are being considered in Minnesota and Ohio.[26]

Discussion

Building on previous research, this study gleaned new insight into the lived experience and challenges faced by students who cannot access their transcripts, degrees, and/or enroll in courses due to institutional debt. The participants in our study were overwhelmingly students of color, women, first generation, and/or from low socioeconomic backgrounds. By presenting their perspective, our study provides a deeper understanding of the ways stranded credits complicate, alter, and derail student pathways towards a degree. All of our student participants began their journey through higher education a long time ago, some as far back as the 1980s, and the reason they have not yet earned a college degree is because of institutional debt they could not afford to pay. In addition to supporting previous research on the impact of stranded credits, our findings offer a more dynamic and nuanced understanding of the ways in which stranded credits affect student matriculation. In particular, we showed how stranded credits can slow a student’s progression towards a degree, discourage them from pursuing a degree, as well as alter their pathway through college and beyond.

Most compelling among our findings are the stories about how stranded credits held students in limbo, with no options for enrolling, transferring, or applying for additional financial aid and job opportunities that could help them settle their institutional debt. This inevitably leads to frustration and reduced self-efficacy about completing the degree. It can also take a psychological toll on students, causing stress, anxiety, and even depression. Consequently, stranded credits can be the difference between a student stopping out of college or dropping out completely and giving up, which inevitably affects career pathways as well.

Our findings demonstrate how stranded credits are both a cause and symptom of inequity in higher education. Students of color, particularly those who are first generation and from low socioeconomic backgrounds, are more likely to lack the financial means to settle institutional debt, especially in the wake of major life changes like job loss, pregnancy, or divorce. Additionally, once they accrue institutional debt, they have very few options for securing additional money or opportunities that can help them settle the debt. This debt is exacerbated if institutions apply additional fees and interest. Additionally many of our participants were familiar with stranded credits, not by name, but because they knew of peers and family members who had institutional debt. This supports our previous findings that the tactic of withholding transcripts, degrees, and preventing students from enrolling is quite prevalent.[27]

This also builds on previous research that shows first generation students may lack awareness about how to navigate institutional processes that can contribute to stranded credits.[28] In some cases institutions make mistakes or have processes that can contribute to a student’s confusion, creating delays that lead to stranded credits. Students who are from low socioeconomic backgrounds and are dependent on financial aid as well as unfamiliar with how to navigate their institutional processes may find themselves out of bounds and in debt they cannot afford to settle.

One of the most disheartening revelations to emerge from our findings is the lack of flexibility and support institutions offer when students seek assistance to settle their debt. The sheer volume of data we collected from social media indicates that many students do not feel supported or know where to turn to get help for settling their institutional debt.[29] All of our participants expressed that institutions need to work harder to be more empathetic, flexible, and creative in helping students resolve their institutional debt so that they can matriculate and access other opportunities that will lead to securing employment that will enable them to pay outstanding balances. There is disagreement in the court system about who bears the responsibility. In a recent case between a plaintiff and Ball State the lower courts found that withholding transcripts cannot be compared to other methods of collecting debt, but the Indiana Supreme Court disagreed and overturned this ruling.[30] In the case, lawyers for Ball State compared withholding transcripts to a mechanic holding onto a car until the fees are paid.[31] This is not a good analogy because a mechanic holds an entire car because they cannot give all of the paid parts of the car back and withhold only the parts they worked on. A college, however, holds transcripts and degrees for credits students have already put labor into and earned. Additionally, many institutions hold transcripts and degrees for minor student fees, even when tuition has already been paid on the courses.

Limitations

This study has a few limitations that we would like to point out. First, it was descriptive, qualitative research and therefore is not designed to be generalized. We had a small, purposeful sample that disproportionately represented one institution. However, while qualitative research is not designed to be generalizable, it can offer critical insight into lived experiences that represent a larger population. Additionally, we did not verify student perspectives with their records or with the institutions, therefore some of the claims about institutional error may or may not be attributed to student misunderstanding or institutional miscommunication. Finally, we only spoke to two staff members, both transfer counselors, therefore, the administrative perspective and response to this topic is limited.

Implications

The findings of our study have many significant implications. First, it is important to note that most of the students we spoke to were enrolled because they are participating in an institutional debt relief program designed to address stranded credits. The one student participant who was not in a debt-relief program was enrolled in an HBCU, and while many of our participants transferred from community colleges, there were no active community college attendees represented in our sample. All of the students taking part in debt relief programs praised them for providing a pathway back to a degree. As we have indicated in our previous report on this issue, debt relief programs can be an effective and cost-effective way to retain and graduate students struggling to pay institutional debt.[32]

More importantly, our findings highlight the way inequity can be reproduced and exacerbated by institutional policies that disparately impact students of color, those from low socioeconomic backgrounds, and first-generation students. This supports previous research that demonstrates students with intersecting marginalized identities experience the most difficulty navigating institutional bureaucracy and are at risk for attrition.[33] Our findings expand on that research by showing how particular intersecting identities (students of color, first generation and low socioeconomic background) can increase the likelihood of students stopping or dropping out due to stranded credits. These students also are more vulnerable to financial instability related to major life changes. This has implications not only for institutional equity practice, but for broader state support for institutions that disproportionately serve these populations. Minority Serving Institutions (MSIs) and community colleges (some of which are MSIs as well) play a very valuable role in higher education, particularly when it comes to access and addressing increasing demand for a diverse workforce.

Not only do MSIs and community colleges support equity by enrolling more first generation, low-income, and students of color but they graduate more of these populations than other institutions. Despite this, MSIs and community colleges do not share the same level of funding and support as predominantly white four-year institutions. These institutions are disproportionately underfunded compared to those universities where mostly White students are enrolled,[34] and this inevitably affects their reliance on revenue generating practices as well as their institutional capacity to track and provide data related to stranded credits.[35] MSIs and community colleges both share egalitarian roots and are known for their ability to offer educational opportunities for students who have been underserved by a stratified system. Unfortunately, while their use of holding transcripts and degrees for institutional debts sabotage their egalitarian ideals and inevitably punish the most underserved and marginalized students, financially strapped institutions like MSIs are also forced to rely on tuition dollars to keep their doors open.[36]

Our findings showcase the human narrative behind the numbers and show how stranded credits impact not only student academic trajectories, but their mental health, careers, and ability to make a better life. Institutions should consider how their policies, practices, and communication can create institutional debt and negatively impact potential future alumni and ambassadors for their organizations. State policymakers and state higher education executive officers (SHEEOs) should prioritize stranded credits on their agendas and work to limit an institution’s ability to hold transcripts and degrees for unpaid balances. State policymakers, and especially SHEEOs should also consider how they can address longstanding systemic underfunding for institutions that continue to support equity by serving the neediest students.

Many scholars have cited that institutional capacity is a key component necessary to effectively implementing financial equity for students.[37] Organizations need funding and resources to counter practices that may generate revenue but also result in stranded credits and inequitable outcomes. It is not even clear how much revenue institutions generate from holding credits and degrees since the only data available about stranded credits is tied to those who are unable to pay. Additionally, research in regard to both capacity building for under-resourced institutions like community colleges and MSIs is very scarce. However there is evidence that MSIs and community colleges face capacity obstacles preventing them from developing alternatives for generating needed revenue and to monitoring data when it comes to tracking stranded credits.[38]

Recommendations

Based on our findings and the extant literature on stranded credits, we have several recommendations for state policy, institutional policy and practice, and research.

State Policy

- SHEEOs should place stranded credits on their equity agenda and focus on how they can work with institutions to limit their reliance on holding transcripts and degrees for payment. This may include implementing restrictions on how institutions treat institutional debt, providing protections for transcript and degree release, supporting capacity building for under-resourced institutions, and supporting efforts to create debt relief programs.

- SHEEOs can hold institutions accountable for how they support the most vulnerable and at-risk students by incorporating reporting on the prevalence of unpaid institutional debt and the way it is being addressed within current accountability mechanisms.

- SHEEOs and other state policy actors could work with institutions to identify alternative solutions that provide students more options for repaying institutional debt and reduce the reliance on practices that result in stranded credits.

- State representatives should work with SHEEOs on legislation that disincentivizes or prohibits institutions from holding transcripts and degrees for unpaid debt as well as creating capacity building efforts that support efforts to develop more flexible and supportive ways for students to settle their debts, including debt relief programs and student-tailored payment plans. However, they must consider the unintended consequences of such bans to ensure students are not simply negatively impacted in another way. For example, colleges may drop students in the middle of the term for non-payment or prevent them from sitting for finals, which may disrupt their educational trajectories. Similarly, colleges may require upfront payments in full for the term, which could create an enrollment barrier for lower-income students. New policies should be properly evaluated and designed to minimize unintended consequences.

Institutional Policy and Practice

- Institutions should consider creating debt relief/assistance programs for students with outstanding balances. These programs should include support for re-enrollment or releasing transcripts and degrees so that students can transfer, apply for scholarships, and employment.

- Institutions should expand their orientation events and curriculum to include more education about financial aid, institutional debt, and resources for students who encounter financial hardship.

- Institutions should include more training and resources for student advisors about financial aid and what options students have when they are unable to pay.

- There needs to be more communication and coordination between financial aid, the registrar, and student support in order to identify and support students who may be at-risk for financial instability.

- Institutions should review their current response protocols for students with unpaid balances, with attention to try to implement responsive processes.

Research

- It was outside the purview of this study to go into specific details about the particular pathways of each student, but narrative research that examines the student experience from the time of initial enrollment to their struggle with institutional debt would yield greater insight into specific triggering events and conditions that increase the likelihood of accruing institutional debt. This type of research may also highlight which stages in a student’s academic trajectory are most vulnerable to this problem.

- Relatedly, more contextually based and institutional ethnographic inquiry on different types of institutions is needed to identify possible capacity and resource gaps as well as institutional structures and processes that are connected to how institutions address outstanding institutional debt.

- We raise the question about whether the structure of institutional bureaucracy may exacerbate or mitigate stranded credits. More investigation is needed on whether “one-stop-shops” that centralize the location of financial aid, the bursar, and registrar office impact the prevalence of stranded credits.

- More cross-case quantitative cost-base analysis is needed on the practice of holding transcripts and degrees to identify just how much money is generated through these measures. These types of analyses should also include consideration for the revenue lost through supporting student matriculation, graduation, and alumnae giving.

- More research is needed on the connection between financial aid packaging, institutional debt, and student matriculation. This research should incorporate frameworks that attend to the intersectionality of first-generation status, ethnicity and race, gender, and socioeconomic status.

- More research on debt relief programs and state policies that explicitly ban the practice of transcript withholding is needed. In particular, examinations of the implementation of these interventions and their outcomes in supporting student matriculation and achieving other goals such as transfer, job placement and securing scholarships.

- Studies that include the administrative perspective are limited. More inquiry that captures the administrative perspective on processes and supports for addressing institutional debt is needed. This research should address the barriers and challenges to creating alternative options for students trying to settle their debt.

Conclusion

Stranded credits are a pervasive and insidious problem because, to date, they are not systematically documented or regulated. The practice of holding transcripts, degrees, and the ability to enroll into classes has flourished as a means to create revenue, and this inevitably affects the disenfranchised who need higher education the most. Stranded credits have a negative impact on equitable educational experiences and outcomes in higher education. For students, especially students of color, first generation, and/or those from low-income backgrounds, stranded credits are the difference between dropping out and earning a degree and securing a better future. For institutions who regard stranded credits as a revenue generating mechanism, this is not an advantageous solution because the very students they target are unable to pay or re-enroll. This not only undercuts retention and diversity and equity goals, but institutions also lose prospective (and well-employed) alumni who can serve as donors and ambassadors for recruitment. Stranded credits also derail state educational and workforce goals, particularly when it comes to improving degree and workforce needs related to populations of color. As a nation, we need to actively work to find solutions that will address and reduce the phenomenon of stranded credits if we are to ever realize the promise of equal opportunity in higher education for all.

Appendix I

Participants were recruited by identifying persons associated with higher education debt relief programs and through LinkedIn professional organizations associated with student affairs and debt relief. Although we emailed the administrators and staff for many institutional debt relief programs, a disproportionate share of our responding participants are affiliated with a debt relief program situated at an institution we will call Midwestern.[39] Not all of our participants were associated with a debt relief program. Some participants were, in fact, unaware that such programs exist. Participants were selected regardless of social identity (race, ethnicity, class, gender, sexual orientation, etc.). However, the overwhelming majority of participants (11) and all of our student participants were persons of color. The only two staff who participated in our study were White. Most of our participants (nine total) were affiliated with Midwestern, a public urban research university that has a main campus located in a mid-western state. The remaining three participants were affiliated with Historical University, a public Historically Black College/University (HBCU), Northeast, a public four-year college, and Northern, a two-year community college. It should be noted that due to the nature of this study, while many of the students are associated with Midwestern, almost all of them have affiliations (and stranded credits) with other community colleges, state colleges, and four-year universities across the country.

A semi-structured protocol was used. We conducted five one-on-one individual interviews and two focus groups virtually through the Zoom platform. To strengthen trustworthiness, we engaged in triangulation using document analysis drawing from data culled from social media platforms. The criteria for the data we selected from social media included personal reactions, experiences, and stories involving institutional debt as it relates to things such as accessing transcripts, transfer, financial aid, enrollment, and job placement. The data we collected included testimonies from Reddit, LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter, with the bulk drawn from Twitter.[40]

Data Analysis

For analysis, we identified key themes and patterns and created analytic questions to assist in refining protocol questions for later phases of data collection. In vivo, pattern, and axial coding were used to categorize the data.[41] The categorization of data began by grouping similar categories derived from the current literature on stranded credits. For example, we identified and categorized the types of students affected by stranded credits as well as types of impacts they have on student trajectories. These thematic codes were helpful for providing an initial lens for sorting through the data. Next, we reviewed our data for emergent ideas, experiences, and perspectives and refined our coding scheme, using axial coding to create categories. Finally, we assessed the categories for predominant themes related to our research questions. To increase trustworthiness and rigor, interrater reliability checks were conducted using a representative sample of interviews to identify discrepancies between coders. To increase the transferability we provide a detailed and “thick” description of the experiences of these students and staff as well as themes that can be applied and examined for future research on this topic.

Endnotes

- Justin Gest, “Majority Minority: A Comparative Historical Analysis of Political Responses to Demographic Transformation,” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, July 22, 2020: 1-28, DOI: 10.1080/1369183X.2020.1774113. ↑

- Shengwei Sun, “Who Can Access the “Good” Jobs? Racial Disparities in Employment Among Young Men Who Work in Paid Care,” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 688, no. 1 (2020), 55-76; Kate Bahn and Kathryn Zickuhr, “The Wage Divide for Black and Latinx Workers Goes Deeper Than a ‘Skills Gap’ or Requiring More Credentials,” The Washington Center for Equitable Growth, February 4, 2021, https://equitablegrowth.org/the-wage-divide-for-black-and-latinx-workers-goes-deeper-than-a-skills-gap-or-requiring-more-credentials/. ↑

- Slicing Sun, Ashley Jackson, Romario Smith, and Darrell L. Hudson, “Race at the Forefront in Social and Economic Inequities,” Journal on Race, Inequality, and Social Mobility in America 2, no. 1 (2020), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/jrisma/vol2/iss1/2/. ↑

- Timothy J. Bartik and Brad J. Hershbein, “Degrees of Poverty: The Relationship Between Family Income Background and the Returns to Education,” Upjohn Institute Working Paper, March 1, 2018, https://research.upjohn.org/up_workingpapers/284/. ↑

- Anthony P. Carnevale, Stephen J. Rose and Ban Cheah, “The College Payoff: Education, Occupations, and Lifetime Earnings,” The Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, https://1gyhoq479ufd3yna29x7ubjn-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/collegepayoff-completed.pdf. ↑

- “Facts & Figures: College Students Are More Diverse Than Ever. Faculty and Administrators Are Not,” AAC&U News, March 2019, https://www.aacu.org/aacu-news/newsletter/2019/march/facts-figures. ↑

- Scott Jaschik, “Redefining ‘Value’ in Higher Education,” Inside Higher Ed, May 12, 2021, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2021/05/12/gates-foundation-attempts-redefine-value-higher-education. ↑

- Andrew Howard Nicols, “Segregation Forever? The Continued Underrepresentation of Black and Latino Undergraduates at the Nation’s 101 Most Selective Public Colleges and Universities,” The Education Trust, July 21, 2020, https://edtrust.org/resource/segregation-forever/. ↑

- Tachelle Banks and Jennifer Dohy, “Mitigating Barriers to Persistence: A Review of Efforts to Improve Retention and Graduation Rates for Students of Color in Higher Education,” Higher Education Studies 9, no. 1 (2019), 118-131, https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v9n1p118. ↑

- Sonya L. Britt, D. Ammerman, Sarah F. Barrett, and Scott H. Jones, “Student Loans, Financial Stress, and College Student Retention,” Journal of Student Financial Aid 47, no. 1 (2017), 3. ↑

- Jen Mishory, Mark Huelsman, and Suzanne Kahn, “How Student Debt and the Racial Wealth Gap Reinforce Each Other,” The Century Foundation, September 9, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/report/bridging-progressive-policy-debates-student-debt-racial-wealth-gap-reinforce/. ↑

- Richard Pallardy, “Racial Disparities in Student Loan Debt,” Saving for College, August 27, 2019, https://www.savingforcollege.com/article/racial-disparities-in-student-loan-debt. ↑

- Julia Karon, James Dean Ward, Catharine Bond Hill, and Martin Kurzweil, “Solving Stranded Credits: Assessing the Scope and Effects of Transcript Withholding on Students, States, and Institutions,” Ithaka S+R, October 5, 2020, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.313978. ↑

- Student Borrower Protection Center Staff and Mark Huelsman, “Withholding Dreams: Why Washington Must Tie COVID Relief for Colleges to Relief for Students Burdened by Institutional Debt,” Student Borrower Protection Center Research Paper, February 2021, https://protectborrowers.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Withholding_Dreams_SBPC.pdf. ↑

- Ibid, pages 1 and 3. ↑

- “Return of Title IV Funds (R2T4),” Federal Student Aid (nd), https://fsapartners.ed.gov/knowledge-center/library/functional-area/Return%20of%20Title%20IV%20Funds%20%28R2T4%29. ↑

- “Return of Title IV Funds Task Force: Report to the Board,” NASFAA, July 2015, https://www.nasfaa.org/uploads/documents/R2T4_Report_to_the_Board_Sept_2015.pdf. ↑

- Keri Murakami “Group Urges Cancellation of Institutional Student Debt,” Inside Higher Ed, February 2, 2021, https://www.insidehighered.com/quicktakes/2021/02/02/group-urges-cancellation-institutional-student-debt. ↑

- “GAO Report: Students Need More Information to Help Reduce Challenges in Transferring College Credits,” The United States Government Accountability Office (GAO), September 19, 2017, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-17-574.pdf. ↑

- Matt S. Giani, “The Correlates of Credit Loss: How Demographics, Pre-Transfer Academics, and Institutions Relate to the Loss of Credits for Vertical Transfer Students,” Research in Higher Education 60, no. 8 (2019), 1113-1141. ↑

- Julia Karon, James Dean Ward, Catharine Bond Hill, and Martin Kurzweil, “Solving Stranded Credits: Assessing the Scope and Effects of Transcript Withholding on Students, States, and Institutions,” Ithaka S+R, October 5, 2020, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.313978. ↑

- All participant names have been masked to protect their identity. ↑

- Eligibility limits and terms for federal financial aid are dependent on many factors relating to income eligibility from year to year and the type of award. More information about the various requirements can be found here: https://studentaid.gov/h/understand-aid. ↑

- In order to protect student privacy, we have chosen not to include specific social media posts. ↑

- An Act Ensuring Students’ Access to Academic Transcripts, Bill S.667, presenter Harriette L. Chandler, 190th Commonwealth of Massachusetts Senate (2017 – 2018), https://malegislature.gov/Bills/190/S667. ↑

- HF 1181, Minnesota Legislature, (2021), ; https://www.revisor.mn.gov/bills/bill.php?b=House&f=HF1181&ssn=0&y=2021; S. B. No. 135, Senator Cirino, 134th General Assembly Regular Session, Ohio, (2021-2022), https://search-prod.lis.state.oh.us/solarapi/v1/general_assembly_134/bills/sb135/IN/00/sb135_00_IN?format=pdf. ↑

- Julia Karon, James Dean Ward, Catharine Bond Hill, and Martin Kurzweil, “Solving Stranded Credits: Assessing the Scope and Effects of Transcript Withholding on Students, States, and Institutions,” Ithaka S+R, October 5, 2020, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.313978. ↑

- Patton O. Garriott and Stephanie Nisle, “Stress, Coping, and Perceived Academic Goal Progress in First-Generation College Students: The Role of Institutional Supports,” Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 11, no. 4 (2018), 436. ↑

- There is evidence that at-risk college students are especially more likely to find the anonymity social media offers is useful for finding social support. See Lauren Reining, Michelle Drouin, Tammy Toscos, and Michael J. Mirro, “College Students in Distress: Can Social Media Be a Source of Social Support?” College Student Journal 52, no. 4 (2018), 494-504. ↑

- “Ball State University v. Irons: Justia Opinion Summary,” Justia US Law, https://law.justia.com/cases/indiana/supreme-court/2015/45s03-1503-dr-134.html. ↑

- Seth Slabaugh, “Ball State Appealing Court’s Decision Against Transcript Holds for Unpaid Tuition,” IndyStar, April 22, 2014, https://www.indystar.com/story/news/education/2014/04/22/ball-state-appealing-courts-decision-transcript-holds-unpaid-tuitions/8005603/. ↑

- Julia Karon, James Dean Ward, Catharine Bond Hill, and Martin Kurzweil, “Solving Stranded Credits: Assessing the Scope and Effects of Transcript Withholding on Students, States, and Institutions,” Ithaka S+R, October 5, 2020, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.313978. ↑

- Satasha L. Green and Constance F. Wright, “Retaining First Generation Underrepresented Minority Students: A Struggle for Higher Education,” Journal of Education Research 11, no. 3 (2017). ↑

- Sara Garcia, “Gaps in College Spending Shortchange Students of Color,” Center for American Progress, April 5, 2018, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education-postsecondary/reports/2018/04/05/448761/gaps-college-spending-shortchange-students-color/. ↑

- Wendy Kilgore, “Stranded Credits: Another Perspective on the Lost Credits Story,” American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers (AACRAO), August 2020,https://www.aacrao.org/docs/default-source/research-docs/aacrao-stranded-credits-report-2020.pdf. ↑

- Krystal L. Williams and BreAnna L. Davis, “Public and Private Investments and Divestments in Historically Black Colleges and Universities,” ACE and UNCF, January 2019, https://www.acenet.edu/Documents/Public-and-Private-Investments-and-Divestments-in-HBCUs.pdf. ↑

- James Dean Ward, Elizabeth Davidson Pisacreta, Benjamin Weintraut, and Martin Kurzweil, “An Overview of State Higher Education Funding Approaches: Lessons and Recommendations,” Ithaka S+R, December 10, 2020, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.314511. ↑

- Alisa Cunningham, Eunkyoung Park, and Jennifer Engle, “Minority-Serving Institutions: Doing More with Less,” Institute for Higher Education Policy, February 2014, https://www.ihep.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/uploads_docs_pubs_msis_doing_more_w-less_final_february_2014-v2.pdf. ↑

- All participants and their institutions are masked using pseudonyms to protect their identity. ↑

- We have masked most of the names/identities associated with social media posts. Even though these were public statements accessible to anyone reading the social media platform, we did not want to draw undue attention to the users. ↑

- Johnny Saldaña, The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers (Sage, 2021). ↑