Addressing Re-Engagement and Re-Enrollment Barriers for New Jersey Learners with Some College, No Degree

Data, Policies, and Solutions

-

Table of Contents

- Executive summary

- Scope and context

- Students with SCND in New Jersey

- Administrative holds

- Past due balances

- Engagement and enrollment supports

- SCND grant impact and perspectives

- Statewide considerations

- Conclusion

- Appendix A: Participating institutions and agencies

- Appendix B: Interview data

- Appendix C: Aggregate data

- Glossary

- Endnotes

- Executive summary

- Scope and context

- Students with SCND in New Jersey

- Administrative holds

- Past due balances

- Engagement and enrollment supports

- SCND grant impact and perspectives

- Statewide considerations

- Conclusion

- Appendix A: Participating institutions and agencies

- Appendix B: Interview data

- Appendix C: Aggregate data

- Glossary

- Endnotes

Executive summary

Re-engaging and re-enrolling adult learners with some college credit but no degree is an increasing priority nationally and in New Jersey. Credential completion not only enables individuals to access higher paying jobs, but also generates tuition revenue for institutions and supports regional economic development. Recognizing this and the other benefits experienced when students return, New Jersey’s higher education institutions and the Office of the Secretary of Higher Education (OSHE) have made significant investments in re-engaging and re-enrolling stopped out students.

Despite these efforts, students still encounter significant barriers to re-enrollment, particularly when unpaid balances and administrative holds are involved. To better understand these challenges, Ithaka S+R and New Jersey OSHE collaborated on a project examining institutional and student experiences with the re-engagement and re-enrollment process, including the impact of New Jersey’s Some College, No Degree (SCND) initiative. This work was made possible by generous funding from Lumina Foundation and The Kresge Foundation.

This report uses mixed methods research to document the challenges students and institutions face, highlight promising practices underway, examine the implementation and impact of the SCND initiative, and identify high-impact opportunities for further work.

Key findings

- Administrative holds are inhibiting New Jersey students from registering for classes. Ambiguous hold resolution processes can create delays for students seeking to re-enroll in their home institution or elsewhere.

- Past due balances continue to be a major barrier for students who wish to restart their education. Beyond leading to administrative holds, these balances can be difficult for returning students to address.

- Proactive outreach strategies and dedicated points of contact are among the most effective approaches to re-engaging stopped out students. However, the capacity and resources necessary for this personalized support are often limited.

- Student-focused incentive funding from the state grant program (SCND grants) are vital for returning students. These grants have helped institutions resolve students’ past due balances and provide emergency basic needs support. They have also helped institutions develop the capacity to expand support for adult learners.

Scope and context

Purpose

Re-engaging and re-enrolling students with some college, no degree (SCND) has increasingly become a priority nationwide to achieve state attainment goals and address the enrollment cliff in higher education.[1] As in other states, New Jersey has made significant investments in supporting the re-enrollment of these students. In 2017, New Jersey set its ambitious “65 by ‘25” attainment goal in response to the growth of workforce demand for individuals with high-quality postsecondary credentials outpacing that of the supply. The goal of 65 percent of working age residents attaining a high-quality postsecondary credential or degree by 2025 prompted institutions and the New Jersey Office of the Secretary of Higher Education (NJ OSHE) to examine ways to re-engage, re-enroll, and support students with SCND. As part of the statewide SCND initiative, NJ OSHE has awarded over $4 million in grant funding, launched a statewide marketing campaign, provided credit for prior learning technical assistance, and partnered with ReUp Education, an organization focused on providing outreach to and coaching for stopped out students, to help New Jersey colleges and universities successfully re-engage, re-enroll, and graduate students with SCND.[2]

As a continuation of this investment, NJ OSHE collaborated with Ithaka S+R to better understand the challenges of re-engaging stopped out students and document the promising practices grantees and other institutions are employing to support students with SCND. This project was guided by four major goals:

- Compile, review, and assess current initiatives across institutions of higher education in New Jersey supporting adult learners with SCND,

- Better understand the scope of stopped out students in New Jersey by identifying and analyzing available data on past due balances and administrative holds,

- Propose ways to improve and build on student-focused incentive funding interventions, and recommend implementation opportunities to address past due balances, and

- Support stakeholders invested in removing barriers to re-engagement and re-enrollment by sharing key insights and findings.

Data collection

To meet these overarching goals, our team used a mixed-methods approach that included gathering aggregated institutional data and interviewing key stakeholders who are involved with implementing the SCND grants and supporting returning students. This section outlines the qualitative and quantitative sources used to inform the analysis and recommendations presented in this report. We also present additional information pertaining to sample, protocols, and the analysis process in the appendices.

Interviews

Between December 2024 and early March 2025, we interviewed over 30 participants from 18 institutions as part of our data collection process (See Table 1a in Appendix B for the breakdown of schools by institution type). These interviews provided qualitative insights into respondents’ perspectives on administrative holds and past due balances, promising practices within re-enrollment initiatives, and the challenges faced by adult learners who want to re-enroll and the institutions that want to re-enroll them. They also provided additional context on how the SCND state initiative and grant funding contributed to institutions’ capacity for effective outreach and re-enrollment. Additional interviews with participants from ReUp Education, the New Jersey Council of County Colleges, the Higher Education Student Assistance Authority, and with the secretary of higher education for the state of New Jersey also provided a higher-level perspective on these topics. We analyzed each interview using a codebook developed by our team, which focuses on themes related to administrative holds, past due balances, the SCND grant, and support for returning learners.

Administrative data

As part of our aggregate data collection, we administered a survey to stakeholders at 21 New Jersey institutions (10 two-year public institutions, eight four-year public institutions, and three four-year private institutions). Our administrative data spanned the years 2013 – 2023. We requested data on the number of stopped out students from that time period, how many of those students had transcript holds for past due balances, how many had a registration hold for a past due balance, the total amount owed by stopped out students, the total amount of debt that has been repaid, and the percentage of debt repaid. We also requested information about policies and practices, such as the past due balance threshold that would historically trigger a transcript or registration hold and efforts institutions have undertaken to re-enroll students who are stopped out.

This report is guided by our goal to better understand support for students with SCND throughout New Jersey and the implementation of the SCND statewide initiative. First, we present a descriptive overview of students with SCND, administrative holds, and past due balances nationally and in New Jersey. We then outline the challenges for both students and institutions related to administrative holds, past due balances, and targeted student supports and highlight promising solutions already in place throughout New Jersey. We then share more about New Jersey’s SCND initiative and its impact and provide recommendations based on key findings from our data collection process.

Overview of some college, no credential population

National context

Re-engaging students who have stopped out has become an increasingly important priority as states and institutions seek to meet educational attainment goals, increase enrollment and graduation numbers, and support individual economic mobility. Many states, including North Carolina, California, Michigan, and Tennessee, have programs targeted towards reconnecting a growing number of stopped out students to institutions in their state.[3] According to recent National Student Clearinghouse (NSC) data, the population of students with some college, no credential (SCNC) at the start of the 2023-24 academic year reached 43.1 million. Of those, 37.6 million were of working age (under 65), which equated to a 2.2 percent increase from the previous academic year. Every state experienced an increase in the number of SCNC students during the NSC data collection period, highlighting the importance of continuing to re-engage and support these students.[4]

NSC data also reveal several positive trends for returning students. The numbers of students stopping out declined for the second consecutive year. In 42 states plus the District of Columbia, the number of students with SCNC who re-enrolled increased, and nationally the numbers of students re-enrolling and earning a credential within the first year of re-enrollment increased by 0.3 percentage points (to 4.7 percent). Students with at least two years of full-time enrollment before stopping out showed particularly promising progress: they were more likely to return, earn a credential within their first year back, continue into a second year, and complete a credential during that second year.[5] These promising trends illustrate the work being done across the nation to re-engage stopped out students and keep them engaged to re-enrollment.

Students with SCND in New Jersey

To meet the state’s specific economic and educational goals, New Jersey OSHE and institutions have made a concerted effort to re-engage, re-enroll, and graduate students with some college, no degree. Although SCNC and SCND are not synonymous (credential encompasses both degrees and other certifications of knowledge), there is significant overlap, and national SCNC data provides meaningful insights related to New Jersey’s SCND statewide initiative, which began in New Jersey’s fiscal year 2023. According to NSC data, the total population of New Jersey residents age 18 or older with SCNC as of August 1, 2023, numbered 840,502 (757,282 for those ages 18 through 64). New Jersey, with 2.3 percent of students with SCNC re-enrolling, slightly lags behind the national average re-enrollment rate of 2.7 percent. However, for the past three years, a smaller than average percentage of students stopped out from New Jersey institutions.[6]

Compared to the statewide data from NSC, Ithaka S+R’s analysis was based on a more limited set of 21 participating institutions. We prioritized gathering data from institutions participating in the SCND grant program. Therefore, the numbers reported for this project differ from the NSC’s latest report. We compare the counts of stopped out students to undergraduate population counts to provide some context for current institutional enrollment capacity relative to the number of students who could potentially re-enroll.[7]

Among the four-year institutions that participated, fall 2023 full-time undergraduate cumulative enrollment was 111,741. Meanwhile, 93,551 students from participating four-year institutions stopped out during the fall of 2013 through fall 2023. The size of the stopped out student population over the decade is equal to 84 percent of the cumulative fall 2023 full-time undergraduate enrollment. The number of stopped out students per institution ranged from 1,204 to 29,025, with a median of 5,854 stopped out students. To put these numbers into perspective, if institutions were to contact and re‑enroll every student who left over the past decade, they would have enough students to fill an entire incoming class.

Among the two-year institutions that participated, fall 2023 full-time undergraduate cumulative enrollment was 71,552. Meanwhile, 173,153 students from participating two-year institutions stopped out during the fall of 2013 through fall 2023. The size of the stopped out student population over this decade represents 242 percent of the fall 2023 full-time undergraduate cumulative enrollment. The number of stopped out students per institution ranged from 1,546 to 40,180, with a median of 15,590 stopped out students. Consistent with national trends reported in the NSC data, more students stopped out from two-year institutions than four-year institutions in New Jersey. See Table 1 for summary statistics for all institutions and Table 2 for cumulative totals.

Table 1. Participating Institution-Level Data on Stopped Out Students in New Jersey

| Metric | Minimum | Average | Maximum |

| Full-time undergraduate enrollment (fall 2023) | 1,904 | 8,728 | 36,588 |

| Count of stopped out students (2013 – 2023) | 1,204 | 12,700 | 40,180 |

| Students who have stopped out (2013 – 2023) as percent of fall 2023 undergraduate enrollment | 21% | 146% | 556% |

Note. n = 21 participating institutions. Data points are at the institution level.

Table 2. Total Figures on Stop-Out Metrics across Participating New Jersey Institutions

| Metric | Total |

| Full-time undergraduate enrollment (fall 2023) | 183,293 |

| Count of students who have stopped out since 2013* | 266,704 |

Note. n = 21. All data points are aggregated from all participating institutions.

*Stopped out students are slightly undercounted because one institution obtained counts of students for approximately half of the reporting period (2017 – 2022).

Barriers to re-enrollment

Learners with some college, no degree (SCND) face numerous barriers when attempting to re-enroll at their home institution or elsewhere. These students may be halted by past due balances, which can result in registration holds or transcript holds that make continuing their education difficult or impossible. While returning students bring valuable experiences and knowledge, re-enrolling them requires targeted enrollment and engagement supports that address their unique needs.

In this report, we share the scope of past due balances and administrative holds in New Jersey alongside the related challenges faced by New Jersey institutions and students. We also describe a number of promising practices currently being implemented by New Jersey institutions to attract back and support returning students. In order for New Jersey to realize its goals around re-engaging students with some college, no degree and degree attainment, three key areas will need to be addressed:

- Administrative holds: Although financial holds, which are the focus in this report, are meant to incentivize students to pay past due balances, they can often be an unintended barrier for students hoping to return. The hold resolution process can also be burdensome and confusing for students and staff alike if practices are not put in place to streamline the process on both sides.

- Past due balances: Finances can play an integral role in deciding whether or not a returning student re-enrolls and stays enrolled. Relatively small amounts at the student level can compound into substantial losses at the institutional level if solutions that allow students to resolve or enroll with past due balances are not implemented.

- Targeted enrollment and engagement strategies: Students with some college, no degree need targeted support from outreach to graduation. For these students to successfully return and graduate, they must feel welcome, supported, and that they will be successful this time around. To achieve both state and institutional goals around re-enrolled stopped out students, both entities will have to allocate resources, time, and capacity toward a targeted and responsive approach.

Administrative holds

Administrative holds are restrictions placed on a student’s account meant to prompt action from the student to resolve the hold. While often triggered by unpaid balances, they can also result from other factors such as missing immunization forms or overdue library materials. These holds can often make it difficult for a student looking to re-enroll at their original institution or transfer to another college or university. Although holds can come in a variety of forms, in this section, we will primarily focus on two of the most common administrative holds related to unpaid balances: transcript holds and registration holds.

This section provides an overview of administrative holds in New Jersey, discusses the impact of the 2024 federal transcript withholding regulation on New Jersey institutions, describes the challenges faced by students and staff related to administrative holds, and presents relevant promising practices being utilized by New Jersey institutions.

Administrative holds in New Jersey

Overview of administrative holds in New Jersey

To better understand the scope of administrative holds in New Jersey, we asked institutions to share data related to stopped out students and holds on their campus. Because the past due balance threshold that triggers a transcript hold tends to be lower than that of registration holds (both for the set of New Jersey institutions and nationally), transcript hold counts tend to be more numerous than registration hold counts. Among stopped out students, transcript holds have also more accurately captured the total number who are stopped out with a past due balance.[8]

Table 3 below provides an overview of institution-level data on students with administrative (transcript and registration) holds. Additionally, Table 4 provides data on the dollar amounts for past due balances at which students have an administrative hold placed on their accounts.

Table 3. Institution-Level Data on Administrative Holds in New Jersey

| Administrative Hold Metric | Minimum | Average | Maximum | Total |

| Count of students who have stopped out with transcript holds | 47 | 2,157 | 5,345 | 28,044 |

| Count of students who have stopped out with registration holds | 114 | 2,662 | 10,363 | 55,912 |

Note. n = 21 participating institutions. Counts of stopped out students include those students who stopped out between fall 2013 and fall 2023. All 21 institutions provided counts of stopped out students and stopped out students with registration holds; however, only 13 institutions were able to provide counts of stopped out students with transcript holds from the specified range of years.

Table 4. Institution-Level Dollar Thresholds at which Administrative Holds are Imposed

| Metric | Minimum | Average | Maximum |

| Minimum institutional dollar threshold for transcript holds (before July 1, 2024)* | $0.01 | $44.34 | $500 |

| Minimum institutional dollar threshold for registration holds | $0.01 | $651.43 | $3,001 |

Note. n = 21 participating institutions.

*As of July 1, 2024, 6 of the 21 participating institutions withhold partial transcripts. Five of those institutions impose transcript holds for balances at or under $50 and one imposes them for balances over $3,000.

Compared to four-year institutions, two-year institutions had generally lower rates of registration holds among stopped out students. This feature of the data is influenced by the large number of students who stop out from two-year institutions, and as registration holds are usually associated with past due balances, it indicates that students at two-year institutions are more likely to stop out for reasons other than past due balances (although finances can still be a contributing factor even without owing a past due balance). Of note, two-year institutions tend to impose registration holds for lower past due balance thresholds than their four-year counterparts. Also of note is that the dollar threshold at which an institution imposes a hold is typically much lower for transcript holds compared to registration holds. However, our counts of the total numbers of stopped out students with transcript holds is counterintuitively lower than the counts of such students with registration holds. This discrepancy is a result of data record and retrieval limitations.

Although we did not explicitly investigate institutions’ data maintenance and retrieval protocols and technologies, we found a variety in use. Our data revealed that the institutional systems and practices, which often differed from one another, presented sometimes unique data retrieval limitations when institutions attempted to access up-to-date transcript hold counts. One specific challenge we encountered at multiple institutions was that when they ceased imposing transcript holds for past due balances, they simply eliminated the flag for such a hold altogether, which deleted both current and historical records of such holds for all students. Another fairly common issue was that transcript hold flags could be updated with a binary code (either 1 or 0), but institutions’ existing data systems could only preserve when the most recent data update occurred and could not record a full longitudinal record of a student’s transcript hold status. Two-year institutions were more likely than four-year institutions to encounter such limitations, perhaps owing to a more diversified set of data maintenance and retrieval practices at such institutions. Going forward, the practical effect of this data retrieval limitation may be minimal because most institutions are no longer withholding transcripts for past due balances. However, this data limitation does inhibit researching historical trends.

Impact of federal Education Department transcript withholding regulation

Prior to a regulatory change from the US Department of Education,[9] postsecondary institutions commonly imposed a transcript hold on student accounts for past due balances. These holds prevented students from accessing transcripts. The practical effect was that students were thereby prevented from transferring their credits to another institution and sometimes unable to produce transcripts for employment purposes, although a number of states and institutions carved out exceptions for the latter condition and some states banned transcript withholding for past due balances altogether. At the New Jersey institutions in this study, transcript holds were formerly imposed for past due balances ranging from $0.01 to $500, depending on the institution. On July 1, 2024, however, the new regulation took effect, and scenarios under which institutions may now withhold transcripts for students’ past due balances are more restricted.

Under the 2024 regulation, institutions may no longer withhold transcripts for semesters in which students received Title IV aid and paid their balance in full. This regulation leaves institutions with two practical options: 1) continue holding partial transcripts for students or semesters not meeting those criteria or 2) cease withholding transcripts altogether.

In the years prior to the 2024 regulation, 19 of the 21 participating New Jersey institutions withheld transcripts for past due balances, while two of those 19 institutions restricted access to both unofficial and official transcripts.

According to Ithaka S+R’s research in New Jersey and nationally, since July 1, 2024, most institutions have eliminated transcript holds for past due balances due to the administrative burden of producing partial transcripts.[10] However, approximately a quarter of the New Jersey institutions we surveyed have elected to withhold partial transcripts for eligible semesters under the regulation. Table 5 below lists the counts of institutions in each category. For institutions that still withhold partial transcripts, those holds are initiated at or under $50.00 for five institutions and at $3,000 for one institution. One of those institutions reported that it still withholds transcripts for fines of any amount, but not for past due tuition or fees.

Table 5. Institutional Transcript Withholding Since July 1, 2024

| Sector | No holds | Partial holds | Holds for fines |

| Two-Year Institutions | 8 | 1 | 1 |

| Four-Year Institutions | 7 | 4 | 0 |

During our conversations with New Jersey institutions, stakeholders shared their perspectives on the transcript withholding regulation and its implications for institutions and students. While many institutions had updated their transcript withholding policies to align with the regulation, there was a lack of communication between the institutions and stopped out students regarding these changes and what they meant in practice. This communication gap appears to stem from several factors. Interviewees reported that there had been limited intra-institutional discussion about the regulation and its potential impacts on students and institutions. Further, several respondents expressed concerns that students may move from institution to institution to avoid paying balances, noting a lack of clear guidance on how to address this issue.

Despite these issues, institutional stakeholders acknowledged that the regulation could help attract students from other institutions and support stopped out students to re-enroll. However, limited awareness among potential returning students reduces the likelihood that students will fully realize the regulation’s potential benefits.

Challenges

Administrative holds can be cumbersome for institutional staff to track and resolve, creating complications for staff and delays for students. To effectively deal with administrative holds, staff members have to acquire, maintain, and appropriately leverage what can be a large amount of information related to different institutional processes and departments. Once they have been placed on a student’s account, ownership of holds can be unclear and difficult to ascertain. One interviewee shared, “Sometimes it’s the human error of who is managing it, not knowing who is requesting the list, who is advising the list, who is removing the holds.” For example, different departments may have the ability to add or remove holds, but not everyone within a department can do so, making it challenging to clearly and quickly identify the right person to remove a hold from a student’s account. Technology challenges and coding errors may also contribute to confusion, as they can make the purpose and resolution process unclear. Institutional staff tasked with assisting students in resolving holds must devote both mental capacity and time to helping students navigate these challenges once a hold has been placed on their account.

Administrative holds can feel punitive for students and disrupt the re-enrollment process. Complicated technological processes and unclear ownership can create a labyrinth for students to navigate once a hold is placed on their account. They may not understand what a hold means or who to contact to start the resolution process. Even after getting that clarity, the process may be delayed by their own capacity to address a balance or successfully toggle between different campus offices. Furthermore, drawn out hold resolution processes can be incredibly discouraging for students facing a constellation of other challenges while working to re-enroll or persist. When asked about the challenges associated with administrative holds, one interviewee explained,

The challenges are the pressure of the student maybe getting discouraged that they’re sitting on a tuition hold and then they lose interest and maybe they’re not having a great semester academically or socially or mentally. And so then, it just compounds the complexity of that young student or an adult student to continue and persist.

Because most administrative holds are associated with past due balances, a student’s capacity to pay the balance often determines the timing of the resolution process. If a student is only able to resolve a balance associated with a registration hold later in the registration process, they may not be able to register for courses that meet their specific academic and scheduling needs. Furthermore, administrative holds and the onus of the resolution process may feel discouraging for stopped out students who are already facing a number of barriers when considering returning or staying enrolled, making it more likely that they will become discouraged.

Promising practices

There are a number of ways that institutions can help make the hold process less overwhelming for staff and students alike. Many New Jersey institutions are already implementing solutions related to administrative holds, including prioritizing proactive and multi-modal communication and facilitating inter-departmental collaboration. Both solutions focus on centralizing information about holds to make the resolution process more efficient and easily accessible for both staff and students.

Proactive and multi-modal outreach

Clear communication, early and often, can help students avoid administrative holds altogether or quickly rectify them and continue on their educational journey. Stockton University uses multiple mediums, including mailers, phone calls, and texts to let students know that they are not registered. This outreach can prompt students to either register or reach out to an advisor and begin the process of resolving the registration hold on their account. The practice of multi-modal outreach can be useful for all students, but can be particularly helpful for stopped out students. Bergen Community College takes a proactive approach to outreach, reaching out to students based on past payment behaviors to help students avoid or minimize holds. A timely, consistent, multi-faceted communication approach allows students to be well informed and helps them proactively problem solve around holds and the associated past due balances.

Close communication with offices that impose holds

Communication between institutional offices is just as important as communication with students when it comes to streamlining the hold process. Inter-departmental communication can help get holds resolved efficiently and, when possible, allows staff to find workarounds for students. Some institutions may opt to formalize this collaboration by taking a one-stop approach and gathering student-facing offices into one space to minimize confusion for students as they navigate the resources they need to address a hold or other barriers. Other institutions may take a more informal approach working to forge good working relationships with other offices, building bridges that students can easily navigate. For example, at Bergen Community College, a positive relationship between the bursar and financial aid departments allows staff in these offices to efficiently discuss options for removing holds and giving students the chance to come back. In some cases, students with large balances can work with an advisor to come to an agreement to avoid or pause a hold. Creating clear and defined pathways for coordination between departments can help make the hold resolution process less time consuming by minimizing back and forth communication and providing easily repeatable next steps.

This section focuses on administrative holds placed on students’ accounts due to unpaid balances, which may stem from outstanding tuition, fees, or other institutional charges. While proactive outreach and inter-office communication can help reduce holds, institutions can also benefit from focusing on solutions for the balances that trigger these holds. The following section explores the scope of past due balances, the challenges they bring to institutions, and promising practices for addressing the balances.

Past due balances

Past due balances can be a significant barrier to students interested in returning to school, as many institutions require full payment before enrollment. With the federal regulation limiting transcript withholding, students with past due balances may favor transferring to another institution that allows more seamless enrollment rather than considering their former institution, even if the latter may be the faster path to degree completion. As a result, institutions may lose out on potential tuition revenue from re-enrolling former students, and data show current collection efforts often return only a small portion of the unpaid balance (See Table 7).[11]

This section examines the scope of past due balances for stopped out students, based on aggregate data from institutions. It also outlines the challenges institutions face in addressing past due balances and highlights promising practices used to support enrollment for students with past due balances.

Past due balances in New Jersey

Overview of past due balances in New Jersey

Among the 21 participating institutions, the cumulative past due balance for students with SCND exceeded $96 million. Students from four-year institutions carried 56 percent of that total, whereas students from two-year institutions carried 44 percent. In Tables 6 through 9, we present average per-student balances at two-year and four-year institutions, data on institutional collection strategies, and return-on-investment calculations for a potential debt relief and re-enrollment plan.

To calculate average balances, we divided reported cumulative balances by the number of students who were stopped out with an administrative hold. When available, we used the count of transcript holds. Otherwise, we used the count of registration holds. This strategy worked for all but one institution, which is noted in the data where relevant. Also of note is that several institutions were unable to provide the percentage of past due balances that they currently successfully collect, either internally or through an external agency. We estimated those institutions’ collection rates at the average of other institutions within the same sector (two-year or four-year). Each sector’s data is presented separately below.[12]

Table 6. Institution-Level Data on Past Due Balances in NJ (2013 – 2023)

| Minimum | Average | Maximum | Total | |

| Total owed by all stopped out students at each institution | $91,257 | $4,601,939 | $15,499,586 | $96,640,720 |

| Two-year institutions | $91,257 | $4,253,179 | $15,499,586 | $42,532,781 |

| Four-year institutions | $710,586 | $4,918,994 | $10,889,315 | $54,108,939 |

| Average amount owed by stopped out students with an administrative hold | $402 | $1,755 | $15,712 | NA |

| Two-year institutions | $707 | $1,411 | $11,974 | NA |

| Four-year institutions | $402 | $2,171 | $15,712 | NA |

Note. n = 21. Data for this table is from fall 2013 through fall 2023. Presented are the cumulative balances owed by all students who stopped out in that span of years at each institution and the average balances owed by stopped out students with administrative holds during the same span of years at each institution.

Table 7. Institution-Level Data on Collections in New Jersey

| Minimum | Average | Maximum | |

| Expected percent of debt collected when students stop out and enter internal or external collections | 1% | 20% | 51% |

| Two-year institutions | 1% | 8% | 48% |

| Four-year institutions | 2% | 27% | 51% |

Note. n = 21. One two-year institution reported a 99 percent collection rate; however, that report was related to a data retrieval limitation. We, therefore, excluded that data point both in the descriptive statistics here and in later calculations of the weighted average collection rate.

Among the two-year institutions, average balances on a per-student basis varied considerably, ranging from $707 to $11,974. Collection rates also varied considerably, ranging from 1 percent to 48 percent, with a weighted average of 8.3 percent. Two institutions could not retrieve their collection rates, so we estimated their rates at the average for two-year institutions.

Average balances on a per-student basis varied at four-year institutions even more than at the two-year institutions. The lowest average balance was $402, and the highest average balance was $6,233. As with the two-year institutions, collection rates varied considerably, ranging from 2 percent to 51 percent, with a weighted average of 27.5 percent. Three institutions could not retrieve their collection rates, so we estimated their rates at the average for four-year institutions. Compared to the two-year institutions, the four-year institutions reported higher collection rates of past due balances from students who stopped out, although overall collection rates were low for both sectors.[13]

Table 8. Institution-Level Data on Balance Thresholds for Use of External Collections

| Past due balance at which institutions refer accounts to external collections | Count of two-year institutions | Count of four-year institutions |

| $25 or less | 3 | 3 |

| > $25 to $100 | 3 | 5 |

| > $100 to $500 | 4 | 3 |

| > $500 to $1,000 | 1 | 1 |

| Over $1,000 | 0 | 1 |

| External collections not used | 1 | 0 |

| Policy under revision | 1 | 0 |

Note. Dollar ranges represent threshold amounts. For ease of presentation, if an institution sends accounts to an external collector for one penny over the upper limits reported above, then the institution is included in that reported range (e.g., institutions that use collections once past due balances reach $100.01 are reported in the “>$25 to $100” range).

Most institutions (14 participating institutions) regardless of sector refer student accounts to an external collection agency for quite low past due balances ($100.01 or less). Time frames after which an account is sent to collection tends to be in the range of six to 12 months following a student stopping out, and one institution reported using an internal pre-collection process immediately after the add/drop period ends. Four of the two-year institutions and two of the four-year institutions were unable to determine how much of the outstanding balances were recouped through external collections. External agency collection rates range from as low as 1.5 percent to as high as 50 percent, and the (simple) average rate is 19.2 percent. We were unable to produce a weighted average because most institutions were unable to determine the exact balance that was referred to external collection agencies, and six institutions were unable to determine the percentage of balances that were recouped via external agencies.

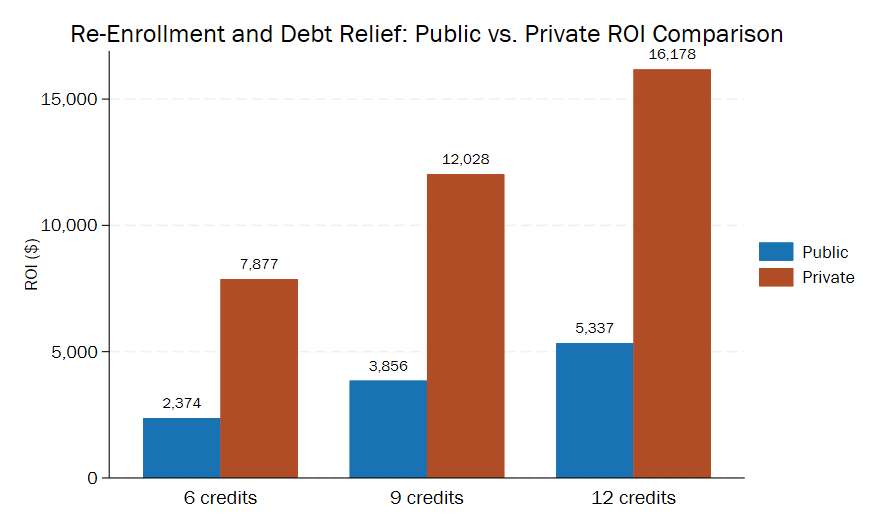

Table 9. Past Due Balance Relief Return on Investment by Sector

| Sector | Average Expected Collection Amount per Student | Average Tuition Rate per Credit-Hour | ROI per 6 Credits | ROI per 9 Credits | ROI per 12 Credits |

| Two-Year Institutions | $117 | $161 | $849 | $1,331 | $1,814 |

| Four-Year Institutions | $597 | $616 | $3,098 | $4,945 | $6,792 |

Note. Weighted averages are based on past due balances and expected tuition on a per-student basis for students who are stopped out with an administrative hold. In calculating the expected collection amount for two-year institutions, we excluded a single institution due to data retrieval limitations.

Based on the reported balance and collection data, we calculated returns on investment for a potential past due balance relief program. The results displayed in Table 9 were calculated by multiplying the weighted average per-credit-hour tuition rate by the number of enrollment hours (six, nine, and 12, respectively) and then subtracting the weighted average expected collection amount. The primary assumption of this return-on-investment (ROI) calculation is that institutions would completely forgo collecting the remaining balance from students who re-enroll and pay their bill for the term.

National examples of re-enrollment programs that include mechanisms for resolving past due balances are Warrior Way Back at Wayne State University, which offers debt forgiveness to returning students with an outstanding balance of $4,000 or less, and the Ohio College Comeback Compact, a partnership of eight institutions in northeast Ohio that resolves balances of up to $5,000 as returning students make progress toward or earn a degree.[14] In the first two years of the Ohio College Comeback Compact, incoming tuition for re-enrolled students was 25 times greater than foregone collections on resolved balances.[15] On average, institutions from both sectors in New Jersey would realize a net positive ROI by implementing a similar balance relief program.

In the case of the participating two-year institutions in New Jersey, a past due balance relief program would net all but one institution a positive ROI after re-enrolling students for at least six credit-hours. Even the institution we noted above with a reported 99 percent collection rate would still benefit from this balance relief plan after students re-enrolled for nine credit-hours.

Similarly, should the four-year institutions pursue a past due balance relief program, they would all net a positive ROI after re-enrolling students for at least six credit-hours. In particular, the institutions with low collection rates stand to generate substantially more revenue from this plan than they would by pursuing a past due balance collection strategy by itself.

Challenges

Past due balances can be a major barrier for students attempting to enroll, particularly because few institutions allow students to register for classes without first resolving these debts. Some respondents shared that they had previously used alternative sources, such as COVID-19 relief funds (CARES Act) or institutional scholarships, to pay down or clear prior balances. However, these federal resources are no longer available, institutional capacity for scholarships and debt forgiveness is usually limited, and existing state aid options often cannot be applied retroactively to cover prior balances.

When describing the scholarships that their office awards currently, one interviewee from a four-year institution remarked “they can only use this aid for the new semesters…if a percentage of it could be allocated…that $1,000 or $500 or $200 might be what makes the difference.” Ultimately, institutions are often limited in the options they can offer students carrying a past due balance.

Some institutions do allow students to carry higher balances into the following semester, but the threshold for those registration holds can vary. Even when this is permitted, there is concern about increasing students’ debt burdens. In another interview, the stakeholder described how in addition to “the financial side, there’s the ethical side, which is if the student already owes the institution money, we should prevent them from owing us more money that they may be unable to pay.” Another stated that they decreased their registration threshold from over $3,000 to over $1,000 because they noticed the balance would grow the next semester and the students couldn’t reduce them. For this reason, institutions have to be intentional about how they approach past due balances with students who want to re-enroll.

In some cases, large balances come from students failing to complete required financial aid verification, a process that is triggered when students are randomly selected by the federal government. The aid cannot be released until verification is completed and it can only be issued for that time frame or semester. While this issue did not come up frequently, it is a possible explanation for large balances. The interviewee shared that “we’ll do all kinds of things to try to contact those students…whatever their internal or external barriers are that prevented them from really understanding the implications of not responding or whatever the situation was, that’s how they get these really large balances sometimes, and it’s very distressing.” Institutions should be aware of this potential outcome and consider proactive strategies to prompt timely responses.

Delays in enrollment can lead adult learners to disengage from the re-enrollment process and potentially stop out again. One interviewed stakeholder described how students “are not very engaged with the institution at that point [of working to reduce the balance to $0 so they can register for classes], so it is very important that we [personalized coaches/dedicated staff or third-party vendor] step in…and help the student to stay very focused on what they are doing and why they are doing it, even if they might not be in classes.” For these personalized coaches and others who support stopped out students, one of the complicated parts of guiding adult learners towards enrollment is keeping them engaged while they are working on the past due balance, especially if the institution has to clear the balance completely before the student can register for classes.

Use of external collections does not necessarily improve how much money institutions recoup, nor does it necessarily improve their ability to track how much is recouped. Our questions about collection rates yielded varied responses. Concerning how many students made payments once referred to an external agency, five of the two-year institutions and two of the four-year institutions were unable to provide information. An additional four-year institution estimated this figure to be 60 percent of stopped out students. For those institutions that could report on that data point, the percentages of students that made payments to an external agency ranged from 8 percent to 60 percent, although the rates tended to skew lower. Six institutions (three two-year and three four-year) reported external agencies collected from fewer than 15 percent of students, and another three four-year institutions reported successful external collection from 25-50 percent of students.

The total percentage of debt recouped through outside collections also varies but skews lower. Six institutions reported that they were unable to determine how much debt was collected by external agencies, and one additional four-year institution provided an estimate of 40 percent, although that institution is currently implementing a system to track that information. One institutional representative explained the challenge associated with obtaining information on collection rates: “The registrar office indicated that this data is difficult to obtain from outside agencies. They do not receive a regular report for this and would need to request from multiple agencies.”

Institutions that had difficulty tracking collection rates for external agencies also tended to have difficulties tracking them for internal collection efforts. Some of the discrepancies between overall reported rates and internal vs. external collection rates indicate some difficulties in disambiguating these figures. For example, one institution was unable to report collection rates for internal collections but shared that the external collection rate was around 8 percent. Meanwhile, they reported their overall collection rate as 46 percent. Such apparent discrepancies are fairly common and indicate that while institutions may perhaps have a sense of overall rates, they lack mechanisms for understanding collection success at a more granular level.

Promising practices

Once a past due balance is on a student’s account, it can be difficult to get students back on the course to degree attainment. Students can lose steam if the process of resolving a past due balance is drawn out, opting not to re-enroll or persist. Additionally, institutions must be mindful of offering options that help students re-enroll without putting them in a compromised financial position. New Jersey institutions have put solutions in place that center student financial well-being while allowing them to maintain re-enrollment momentum, including offering flexibility in payment options and connecting students with support for past due balances.

Processes for connecting students with support for past due balances

A core part of helping students pay down the balance is having processes that allow adult learners to connect supports that can help them navigate the process of addressing the balance. This can involve identifying and sending personalized messages to students who meet the criteria for re-engagement programs. Participants from William Paterson University described how, for FY24, they identified students with prior debt and used SEO messaging to reach them. In addition to having the director of degree completion and adult learning email them about the debt resolution opportunity offered by the institution, staff worked closely with designated colleagues in financial aid and student enrollment services to resolve the balance using SCND grant funds. A similar balance relief program is available at one community college for students who owe less than $1,000 and require 15 or fewer credits for degree completion through a past due balance resolution campaign. In their survey response, participants stated that the balance relief program was part of an ongoing campaign and that they initiated contact with eligible students who had stopped out since the fall 2023 semester.

At Felician University, students who officially withdraw and become stopped out are reached out to by a re-admit team that connects them with academic advisors who offer guidance on re-enrollment and registration. In parallel, a collections specialist contacts students with unpaid balances to demonstrate their intention to resolve the debt instead of pursuing collections. The personalized letters emphasize the importance of resolving balances to avoid future complications and outlines flexible payment options. They also offer potential balance resolution upon successful re-enrollment and graduation.

At Camden County College, students usually cannot register for classes if their past due balance is at or above $250. However the back-on-track program manager can ask the bursar office to replace that hold with one that requires the student to meet with them before registering, so that their progress can be tracked. During the meeting, these students are able to learn about the balance deferment option that allows students to register, come back and apply for financial aid. By prioritizing connecting students with support around past due balances, institutions can help students see their options related to re-enrollment or staying enrolled.

Flexibility in payment options and balance relief funding sources

The most promising practice described by participants centered on giving students more flexible options to pay down balances while registering, including using a combination of resources to assist them with reducing or clearing the balance. Some participants described how returning students with a balance can register if they develop a payment plan for the past due balance or have a plan to discuss their options with the financial aid office. At the New Jersey Institute of Technology, students with certain balance amounts are allowed to register if they communicate with the financial aid office about their plan to resolve it. Previously, students had to pay the entire balance to apply for readmission. At Felician University, which has a higher registration hold threshold (up to $3,000), students are encouraged to use payment plans. Another interviewee mentioned that they had an easier time keeping students engaged if they were able to register while on a payment plan.

Other institutions described using alternative funding sources, including the SCND student-focused incentive funding, to help students to pay down the balance. At Atlantic Cape Community College, staff have students who seemed determined about returning to school go through a process that was similar to a financial aid appeal process. After the student completes the first half of their first return semester, the institution pays off the balance. Atlantic Cape used pre-existing funding specifically for returning students towards this balance. The funding source was a gift from the Atlantic Cape Foundation to the college. Similarly, Rowan University has been funding past due balance relief through access to a scholarship through the university foundation that can be used to support SCND students who are making academic progress.

Many interviewees mentioned using some of their FY24 SCND grant funding to help students pay down or clear past due balances and those from FY25 grantee institutions planned to continue using them to reduce or clear the cost of these balances. In cases where the limited funds could not cover the entire balance, one participant described how “there is a subpopulation of students for whom a limited amount of assistance is actually enough of an incentive to get them to take action to be able to re-enroll.” In one instance, she offered $1,000 towards a student’s $3,000 balance and the student was willing to come up with the remaining amount in order to re-enroll. This highlights the momentum that can be created by offering stopped out students even a partial solution to help them re-enroll.

Past due balances, of even relatively small amounts, can be significantly prohibitive for students hoping to re-enroll. Therefore, it is important for institutions to offer balance relief options or options for students to re-enroll with a past due balance. Institutions can consider programs that waive students’ outstanding balances upon enrollment in or successful completion of credits. Also, relief options targeted towards students who are close to completion can maximize institutional investment. Providing these options allows students to re-enroll and institutions to access additional tuition dollars that usually far exceed the past due balance covered by the institution.

Engagement and enrollment supports

Adult learners with SCND face a number of challenges when re-enrolling beyond administrative holds and past due balances. Like three in five higher education students today, adult learners experience basic needs insecurity including food, housing, childcare, and transportation.[16] Many challenges reflect the multiple responsibilities adult students have, including jobs and caregiving roles that require flexible class times, modalities, and support options. More often than not, institutions are built for students who can participate in an on-campus experience that offers services and daytime classes Monday through Friday. Still, other challenges reflect adult students’ intersectional experiences as low-income, parenting, rural, veteran, and/or justice-impacted students. Together, these challenges require support that centers students’ needs across academic and social domains.

Engagement and enrollment supports in New Jersey

Of the 21 participating institutions, 16 reported the use of proactive outreach campaigns to students with SCND. The usual process for institutions is to regularly review student records to identify students who are stopped out and to then begin outreach via email and/or physical mailers. Institutions also utilize text, phone, and social media campaigns. Multiple institutions indicated that this work was possible because of state support to partner with ReUp. For example, Rowan University indicated that their decade-long effort to proactively contact and invite students to return was “greatly enhanced starting in fall 2023 when Rowan joined OSHE’s statewide partnership with ReUp, which provides high levels of expertise and communication with Rowan’s former students to facilitate their re-enrollment.”

A common strategy for helping students to re-enroll is to establish a singular person or office that students can work with to coordinate tasks, including resolving holds. For example, County College of Morris stated that they have had success by “creating one starting point of contact and adding a network of support systems once they [students] meet with advising to help them move through any holds or barriers to return.” Other institutions do not necessarily employ a single point of contact, but they do ensure close coordination between the multiple involved offices and provide students with guidance. For example, William Paterson University stated that they provide “students with clear instruction on how to resolve the hold and their next steps by scheduling an appointment with the designated financial aid counselor.”

Institutions also credited flexible payment plan options and debt relief programs as effective mechanisms for re-enrolling students with SCND. For example, Hudson County Community College works with students with a balance to offer a deferred payment plan. Once “the student enrolls in a payment plan, and makes their first payment, they will not be deregistered from their classes for that semester.” One college reported that, in exceptional cases, students could be offered “customized payment plans that allow [them] to enroll with a registration hold.”

Concerning past due balance management tools, four two-year institutions and five four-year institutions reported use of payment plans, four two-year institutions and three four-year institutions used balance waivers or debt relief measures, one two-year institution and six four-year institutions offered returning scholarships (Table 2b in the Appendix C).

Challenges

Finances are a barrier for returning students even if they do not have to contend with a past due balance upon re-enrollment. As one interviewee shared,

In the aggregate, finances is a big part, either prior debt or how you are going to pay it this time and making that balance…We have these accelerated, seven-week sessions for our online programs and students will opt to stop out because it is a choice. Am I going to do this thing for my kids or pay for these classes?

Affordability remains a major concern for returning students, as they often have a constellation of other financial priorities they must balance along with paying for coursework. Moreover, financial aid policies may make it difficult to draw on the aid needed to afford a degree. For instance, Satisfactory Academic Progress (SAP) requirements mandate that a student maintain a specific grade point average (GPA) and stay on track to graduate within a designated timeframe. During interviews, respondents shared that this is particularly problematic for stopped out students because their academic performance was likely impacted when they stopped out. Additionally, often non-linear progress means they will take longer to complete a degree. Altogether this makes it difficult for returning to access federal financial aid when they need it. There are some options to regain eligibility for financial aid when SAP requirements are not met, including an appeal process and GPA forgiveness programs, but these processes are not widely utilized, as they are only helpful in certain cases.

At the state level, interviewees also noted that there are fewer non-loan aid options available for students attending school part time at four-year institutions in New Jersey. Because students with SCND are often juggling multiple responsibilities, including employment and caretaking responsibilities, they are not often able to do coursework full-time. Limited financial options for four-year institutions may leave these colleges and universities out of reach for returning students. Federal and state financial aid programs can also have credit cutoffs that bar students from accessing additional aid once they reach this threshold, creating a potential barrier. Students with SCND are likely to have non-linear trajectories that put them beyond credit thresholds and keep them from receiving necessary financial support, even in cases where they may be close to graduation.

As noted previously, stopped out students are likely to be dealing with competing priorities, including financial and familial responsibilities, making it difficult for them to integrate coursework into their lives. Interviewees repeatedly noted that juggling priorities was a key challenge in getting students enrolled and keeping them enrolled, as returning students would have to find both the time and money for coursework in circumstances where they were often already spread thin. One respondent said, “Often their primary role in life is more as a parent and as an employee and as a, you know, kind of some of those other adult responsibilities, if you will, and so fitting in college on top of that can be very challenging.” These hurdles are not only present at the start but often recur throughout a returning student’s journey, making consistent institutional support necessary. Due to limited time, students with SCND are looking for affordability and efficiency as they consider re-enrolling at an institution. Learners may prefer more programs with hybrid or online formats, which allow for scheduling flexibility, or accelerated programs that offer a fast track to degree attainment to save time and money. Since implementing these kinds of programs can be difficult for institutions logistically and capacity wise, some do not offer them. Once again, limited options may put certain institutions and degree pathways out of reach for students with SCND due to the restricted resources they can allocate to coursework.

During our conversations with institutional stakeholders, several interviewees noted that lack of student confidence and belonging made for a substantial barrier to re-engagement. One interviewee explained, “It is a sacrifice on their end, and they think about this because now this time around they’re like, I don’t wanna mess up, I wanna be sure I graduate this time around.” Stopped out adult learners may have negative feelings around college based on previous experiences, and a structure that does not seem to appeal to them (e.g., services that close at 5pm, extracurriculars that are solely in-person, or degree programs that cater to residential students) can reinforce their feeling of not belonging. Students stop out for a number of reasons, but time away from an institution does not usually erase them. If a student academically struggled or could not balance coursework with working full-time or parenting responsibilities when they stopped out, they may be less confident in their ability to overcome these challenges and be successful during another try. Relatedly, if a student halted their initial enrollment because they did not receive adequate support from their institution, it is difficult for them to trust that they will now find the support they need. The longer students are stopped out, the harder it is to override these narratives and convince them to re-engage.

Students with SCND bring credits and experiences from multiple sources, and it can be difficult to articulate and apply previously earned credits to relevant degrees, including operationalizing credit for prior learning (CPL). As noted in a few interviews, the state’s higher education institutions operate within a fairly decentralized structure. Without consistent guidelines, evaluators may not view certain credits from other institutions as transferable, as course objectives and degree requirements can vary widely from institution to institution. Credit articulation can be especially complicated because it requires coordination across multiple departments. One interviewee from the New Jersey Council of County Colleges noted that while the state is focusing on expanding CPL, a more consistent focus on ensuring students are aware of CPL opportunities and on implementing best practices for CPL processes—particularly in resource-intensive areas like portfolio assessments—is needed.

Some institutions rely on services from Thomas Edison State University and the New Jersey Prior Learning Assessment Network (NJ PLAN) or develop their own CPL policies and faculty training. However, as one interviewee noted, a streamlined, statewide process or guidance would be more effective than each institution building its own. Institutions also often rely on external organizations to evaluate real-life or work experience for academic credit—efforts that require both coordination and financial investment.

Returning students often travel non-linear trajectories, as their interests and goals change over time and so do their preferred majors and programs. This can potentially make a student’s pathway to a degree longer and cost students with SCND extra time and money. Returning students may “lose” credits they previously earned if the coursework was not closely related to their current program or did not fulfill general education requirements, pushing the finish line further out. A delayed degree can be frustrating for students and can be exacerbated by financial aid policies related to credit accumulation and satisfactory progress. Maximizing credit transferability and degree applicability of transfer credit while maintaining academic rigor is key to making degree completion more affordable and achievable for SCND students.

Several individuals expressed concerns about maintaining the funds and capacity needed to effectively support returning students. Many respondents emphasized the importance of a concierge approach, where students depend on a single point of contact to navigate institutional processes. As one respondent explained, “The adult learner…has those constraints, and that’s why they need that more concierge-type assistance.”

Because returning students often juggle school alongside work and family responsibilities, minimizing barriers is essential. Staff dedicated to supporting this population noted that strong relationships were key to keeping students engaged. However, expanding this support model is difficult without additional staffing and resources.

Some institutions also expressed uncertainty about whether current levels of state funding could continue. As is described in the next section, state support made it possible for institutions to increase their capacity and provide direct support to students, but in most cases it was unclear how institutions planned to sustain these efforts long-term without ongoing state and institutional investment.

Promising practices

Returning students face a number of unique challenges related to finances, balancing priorities, confidence, and credit loss, and we encourage institutions to address these interconnected barriers. Using existing models in New Jersey as a foundation, we identified a set of promising practices related to providing targeted enrollment and engagement support for learners with SCND that can help encourage successful credential attainment, including dedicated points of contact, strategic partnerships, credit retention solutions, and expanded services.

Dedicated point of contact or office

Assigning a point of contact or office to provide concierge-like services can help address each of the challenges faced by students listed above by providing students with responsive support rooted in consistent communication and connection. Many of the institutions we spoke with had one or more staff members dedicated to supporting returning learners and helping them circumvent common barriers to re-enrollment. For example, Rowan University has a degree completion specialist who identifies holds and helps returning students ascertain whether their current credits align with their program of interest. Having a dedicated person helping returning students with these key activities streamlines the process for students and helps them efficiently restart their educational journey. Although this can be capacity intensive, respondents repeatedly shared stories of students expressing gratitude for the tailored support they received and how pivotal it was for their persistence.

Strategic partnerships

Develop strategic partnerships that expand institutional capacity while providing students with SCND the support they need throughout the re-enrollment process. Several interviewees noted that their institution’s participation in the statewide ReUp partnership made a positive impact on their ability to support stopped out students. ReUp added needed capacity for outreach and helped keep students engaged throughout the re-enrollment process and after they have successfully re-enrolled, including in the midst of competing priorities. ReUp is a national organization that partners with statewide systems and individual institutions to provide outreach to and coaching for stopped out students. As a part of New Jersey’s SCND initiative, a subset of institutions worked with third party vendor ReUp to re-engage students with SCND. ReUp’s targeted and responsive support for stopped out students provides timely communication and guidance that helps students successfully re-enroll and stay enrolled. Conversations with ReUp coaches can help recenter students on their goals when other priorities are competing for their time and resources. The County College of Morris noted that ReUp supplements their engagement with students by facilitating both initial and consistent outreach throughout the re-engagement process and helping support students off campus. One interview participant described the initial outreach that ReUp does as a supplement to their institution’s active engagement with students, which “strengthens their connection with [the college] and keeps it very much in front of them, knowing they have a team who’s in their corner on and off campus.” Strategic partnerships like that with ReUp allow institutions to leverage external expertise and capacity to reconnect with students.

Recognizing acquired experiences with credit

Establishing policies that maximize recognition of acquired experiences with credit addresses challenges related to credit loss and evaluation, competing priorities, and affordability. Some New Jersey institutions have implemented policies that allow students to retain a significant amount of credits from other institutions. Saint Elizabeth University allows up to 90 transfer credits, requiring students to take a quarter of their degree at the university. As a part of their dedication to increasing affordability, Saint Elizabeth also helps students with pre-approvals for more financially feasible community college courses if needed. Similarly, William Paterson University imposes no limit on the number of transfer credits accepted, however students must fulfill the required minimum number of credits at the university as outlined by the undergraduate degree policy and meet the course and grade criteria for their program of study. They also work with students to translate their previous experiences into credit towards their degree by offering many opportunities to get credit for prior learning. Such policies allow students with SCND to maximize the experiences they bring upon their return, effectively achieve degree attainment, and save time and money.

Expanded hours for core services

Providing services to students outside Monday through Friday, 9am to 5pm, helps make services more accessible. Several interviewees shared that grant funding through the SCND initiative made it possible for them to offer expanded hours for core services to better fit the schedules of returning learners. Felician University was able to expand financial aid office hours to assist with FAFSA filing, an often complicated process that can act as an early barrier for returning students. Similarly, the New Jersey Institute of Technology extended hours for tutoring services to help ensure students with SCND received the academic support they needed. Because coursework and support services are often structured to meet the needs of full-time, in-person students, returning students may not be able to see themselves prioritized by an institution. Extending service hours or offering flexibility can reassure students that they will be able to access the support they need to be successful.

Areas for state-level impact

New Jersey institutions are working hard to implement programs and policies that meet the unique needs of students with SCND. However, there are some areas where additional state-level interventions are likely to have a greater impact. For instance, institutions described looking for ways to resolve past due balances and provide scholarship support on a flexible basis. New Jersey has an opportunity to build on state investments in affordability and re-engaging students with SCND to more comprehensively address challenges around finances and financial aid. Modifications can be made to state financial aid programs to make them more accessible to returning students, including increasing credit thresholds and allowing part-time students who want to continue their education at four-year institutions to access more non-loan aid options. The state should continue to review existing aid programs to assess their accessibility for students with SCND and implement modifications, where feasible, to enhance equitable access for these students.

Institutions also shared they were maximizing capacity to serve as many stopped out students as possible, but as these initiatives grow, current or reduced staffing may lead to these students not getting the support they require. As concerns about budget cuts grow, entities like OSHE have an opportunity to incentivize institutions to prioritize students with SCND and allocate needed capacity to serving their needs through avenues such as performance based funding models. These opportunities for state-level impact build on the foundation of investment created by the state.

SCND grant impact and perspectives

Overview of the SCND grants

Through New Jersey’s state-wide “Some College, No Degree (SCND) Initiative,” the Office of the Secretary of Higher Education is using a multi-pronged approach to re-engage and re-enroll residents who have earned some college credit but left school before completing their degree.[17] In addition to facilitating partnerships between ReUp Education and 22 New Jersey higher education institutions to provide outreach and coaching to adult learners who stopped out, OSHE has also awarded two cycles of grant funding to public and independent-public mission higher education institutions that receive state operating aid to support their efforts to engage these students to re-enroll and complete.[18] The goal of these institutional grants, which include a student-focused incentive and an institution-focused funding component, is to address the barriers to returning to higher education and to help institutions build the capacity to serve this population.

This section of the report provides an overview of how institutions have used the grant funds, particularly the student-focused incentives component, to re-engage and re-enroll adult learners, how institutions interpreted the impact of the funding on their efforts, and their goals for utilizing grants. This section also includes a review of the grant program challenges and suggestions for how supports can be improved for the future.

SCND grant impact

Student outcomes based on common strategies

Ithaka S+R reviewed the narrative reports from the FY24 grantee final report to identify common themes in how the grants were used and review the metrics used to describe outcomes. The interviews with institutional representatives also included questions about their interpretation of the impacts of the grants and some of the challenges of administering the grants. Quotes and stories from these interviews are included throughout to incorporate the staff perspective.

While not all FY24 grantee institutions provided the same metrics when describing the impact of initiatives, some common ways of quantifying those results included the self-reported increases in SCND student enrollment and retention, and the number of credits completed by returning students. Some other metrics reported by institutions included engagement metrics for digital marketing campaigns, engagement with advising, number of students “served,” number of graduated students, past due balance remittance granted to students, and more.

Overall, most of the institutions who mentioned enrollment (or returned students) described enrolling a significant portion of their initial target group and increased persistence rates between semesters. Outreach initiatives (through partnerships with ReUp Education and institutions’ own efforts) helped to scale outreach. Table 10 below is a high-level summary of the most common intervention types in the FY24 final reports.

Table 10: Common Strategies and Interventions from FY24 Final Reports

| Cited Strategy or Intervention | Number of Institutions using the Strategy |

| Student outreach (text, calls, emails, targeted digital marketing) | 15 |

| Direct assistance to students (gift cards/vouchers, basic needs support, stipends, application and exam fee waivers, emergency funding, enrollment incentives, past due balance relief) | 14 |

| Personalized support from admission to completion | 13 |

| Website redesign | 9 |

Student outreach

Almost every institution described using some form of outreach (either with ReUp Education, through their own marketing team or another third-party service provider, or both) to re-engage students. From March 2024 to August 2024, County College of Morris reached over 3,500 students and enrolled 891 students through ReUp’s outreach and the college’s marketing and onboarding efforts. Rowan College of South Jersey developed an email campaign in collaboration with a marketing company that also developed a webpage for stopped out students. Between June 25 and September 30, 2024, nearly 300 of the almost 20,000 students who opened the email clicked the link and over 100 students completed interest forms on the webpage.

Direct assistance: emergency aid, vouchers, and past due balances