Community Reflections on Ithaka S+R’s report about Digital Preservation and Curation Systems

In July 2022, we shared our findings from a broad examination of the digital preservation and curation systems landscape, drawn in part from deep dives into a number of third-party preservation platforms. Along with this research, we’ve held a series of online forums to gather feedback on the report from the community. Here, we synthesize what we heard during five invitation-only and three open webinars with 253 people, including preservation service providers, curation specialists, technologists, and representatives from funding agencies.

Digital preservation is about people

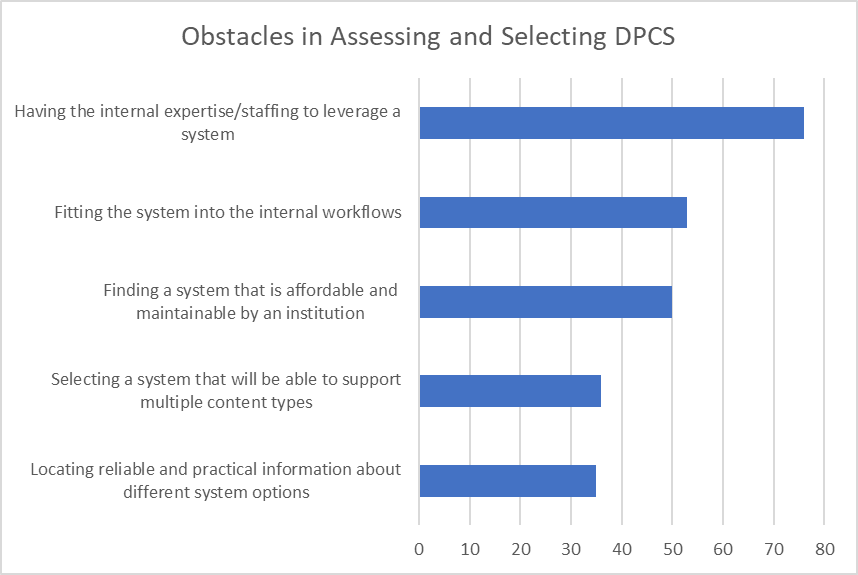

In our report, we defined digital preservation and curation systems as the tools and services used by heritage organizations to undertake digital preservation and curation work in the context of their institutional needs and priorities. But the implementation of these tools, and the responsibility of preserving digital content, falls to the staff at the heritage organizations themselves. Throughout our forums, participants stressed the human nature of digital preservation and felt that social context is a determinant: “It is about people and organizational commitment.” A poll during our open webinars revealed that the top obstacle heritage institutions face in assessing and selecting preservation and curation systems was having the internal expertise and staffing to leverage a system. As one preservation specialist commented, “Turnkey systems would not be able to account for particular things about the institution. That’s why we have a digital preservation profession.” While the systems are essential, digital preservation cannot be said to be sustainable without adequate and appropriate professional staffing.

Labor and climate

As heritage institutions face resource challenges and competing needs, many participants voiced their concerns about “serious labor issues that undermine effective digital preservation.” As the NDSA staffing surveys indicate, there continues to be a misalignment between digital preservation practitioners and senior institutional leaders about how work is prioritized, funded, advocated, and organized. One participant in the discussion sessions noted that “misalignment can create a sense of not being heard and lead to burnout and frustration for preservation specialists.” There is an urgent need for preservation organizations to engage in research and development to meet future needs; however, some systems communities are already stretched thin and face challenges in committing sufficient time into future scoping. In a non-profit setting, as some forum participants noted, the business models might be too reliant on the labor of volunteer contributors that could be difficult to track and quantify.

Entry and exit strategies

From a sustainability perspective, participants stressed the importance of considering both entry and exit strategies when assessing and selecting systems. As one stated, “Digital preservation is a road, it is a journey. Strategies and systems need to evolve and change over time. It is an open-ended and long-term vision.” Participants noted that libraries view migration as part of a natural lifecycle while selecting and managing integrated library systems (ILS). They plan to move to a new system periodically. A system provider added that they would like to see greater transparency about institutional succession planning so that they can avoid locking in customers to one system or another. Some felt that our research needed to consider the sustainability of content and stewardship, rather than sustainability of technologies deployed for long-term content management.

Institutional diversity

One of the research questions behind our project was whether the systems designed for preservation and curation are taking into consideration the needs of institutions with different resource levels and missions, specifically historically black colleges and universities, tribal colleges, and museums focusing on minoritized communities. Some felt that we did not address this important question directly in our report. As one of the participants put it, “I had trouble seeing any equity and diversity issues involving underrepresented institutions represented in the report. If the answer is ‘no, their needs are not being met’ you should openly acknowledge it.” As they were discussing the impact of their grantmaking activities, one of the funder participants stated,“Bigger institutions can put in big applications; however, we don’t see a trickle down effect for smaller organizations to benefit from it.”

Sustainability of funded projects

Funding agency participants revealed that there is often confusion and overlap between the notion of preservation and sustainability. In particular, there is a sense that not only do digital systems need to be sustainable but also heritage organizations themselves: “The overarching issue is that we are concerned about the sustainability of the library as an entire organization.” The discussions confirmed that the question of transitioning open source software systems to a sustainable model has been a key dilemma for all funding organizations: “We need blameless post mortems. We haven’t evolved our ability to address successes and failures with that level of transparency.”

New models for collaboration

Some participants worry that digital preservation is relying too much on the organizational structures and staffing that were built for a traditional analog model and that these staffing structures can lead to professional silos. Even though many libraries are engaged in digital preservation, new complex formats and copyright policies have strained their approaches and resources. Engaging in collective approaches is seen as one of the strengths of the heritage community, as evidenced by a grant made recently to Educopia, who is partnering with six members of the Digital Preservation Services Collaborative (APTrust, Chronopolis, CLOCKSS, LYRASIS, MetaArchive, and Texas Digital Library) to study the feasibility of creating a collaborative community-supported digital preservation service. Some feel that, given that it is a grand challenge, digital preservation needs to be tackled through capacity building and collaborative collection building and maintenance. Stating that the “act of curation is the act of preservation,” several participants mentioned that they find the NDSA model the most helpful in practice, especially in means of providing a common framework for preservation practitioners when building or evaluating their digital preservation program.

Advocacy for preservation

One of the topics that emerged in multiple discussions was the importance of systematic and ongoing advocacy and the need to seek common ground among individuals involved in decision making. A wide range of staff are involved in decision making, and it is complicated to align their expectations, especially given that each individual approaches preservation from the perspective of their functional and organizational involvement. “How do you engage in conversations at the executive level about preservation with sustainable outcomes so that we don’t need to loop back to the same conversation?” asked one participant. Digital preservation is a detail oriented practice, and it is tricky to communicate technical terms at a strategic level to get the attention of decision makers. Systems that are marketed as preservation solutions are providing vastly different services (including some that are essentially workflow tools for commercial cloud storage), causing confusion in efforts to advocate for “preservation.” One of the heritage organization staff participants said, “I even have difficulty in defining and differentiating systems as an expert, so no wonder higher management has trouble with it.”

Commercial and values-driven digital preservation

There were several discussions across the workshops about the differences between commercial and values-driven digital preservation and how—if at all—to compare between them. Several participants highlighted the importance of transparency and accountability in the system assessment process. As noted in the report, because of a lack of financial and technical transparency, the sustainability of commercial systems can be difficult to assess. One participant questioned our decision to compare not-for-profit and commercial systems at all. Another felt that we were promoting the commercial solutions, which might lead to undervaluation of the values-driven approaches taken by many not-for-profit and community system providers, noting that this can be “harmful and play into the marketing campaigns of commercial service providers.” And another person felt we were too critical of the commercial solutions, suggesting that at least some of them are also values-driven or at least community-focused. It is clear that there is a broad spectrum of views about how best to assess the marketplace from a commerciality perspective, particularly at a time when some observers believe there is real growth in the market share of commercial providers.

Multi-system approach

We heard again and again that many heritage organizations need to depend on multiple system providers to meet their preservation needs. As one participant noted, heritage organizations take different approaches to preservation and therefore some are implementing multiple systems for different purposes based on their needs, budgets, experiences and content types. Rather than implementing monolithic systems that can try to address a range of needs, institutions try to integrate disparate systems that do specialized tasks. Participants also raised that many heritage organizations rely on community-based efforts such as peer assessment frameworks that aim to help these organizations document their digital preservation successes, identify gaps and challenges, and pinpoint areas for further growth (for instance, see the tool designed by the Northeast Document Conservation Center). Such efforts enable institutions to collaborate with others to gain an outside perspective in reviewing their staffing, policies, processes, workflows, and technological resources.

More systems to explore

Some questioned why the study was limited to eight systems in different categories although it was obvious that we were “comparing apples to oranges,” and wondered how the small sample size might have shaped our conclusions. For instance, the governance models of not-for-profit service providers vary and have different characteristics in terms of their income resources, reserves, roadmaps, governing structures, etc. We decided not to include programmatic preservation providers in our study, and a deeper dive into what they offer might have provided a more nuanced overview of the digital preservation landscape.

Areas for further study

Throughout our conversations, participants raised questions that, while out of the range of our study, deserve attention. We list some of these here, and are eager to hear what other research questions we should pursue as we continue our inquiry into the digital preservation landscape.

- Given the range of meaning attached to “preservation,” how can we refocus the term or provide an alternative in a way that would provide greater specificity and find broad acceptance?

- Can heritage organizations reclaim societal responsibility for preservation or should their role be reframed to focus on the types of content for which they are in fact working to preserve?

- Does the diversity of staff within the preservation community (experts, decision-makers, system/service providers, etc.), including participation by people of color, bring adequate representation, especially in governance?

- Is the community effectively preserving a representative sample of heritage, including those from historically underserved communities and to ensure that an appropriate diversity of perspectives and voices are included in the cultural record?

- Making something available digitally is not itself preservation. As a service provider said, “I deal a lot with organizations that cannot sustain the collections they have.” How can we better empower those organizations without the resources to sustain their existing collections?

- How can we address the disconnect between the staff on the ground doing digital preservation work and those in senior positions with authority for strategic directions and resource allocation?

- What is being done in the preservation community to assess and mitigate the environmental impact of digital preservation and how can digital preservation become more environmentally sustainable?

In the coming weeks, we will publish additional posts based on the feedback we received through the digital forums. Next up—a discussion of “community control.”