Evaluating Success in the Midst of a Protracted Pandemic

Four Guiding Principles

There was a “before” and there will be an “after,” but how do we evaluate success while at our current locus—somewhere in the nebulous middle of a prolonged pandemic?

More than a year into the pandemic, many evaluations are being conducted using measures of success that were established in a radically different context. The environment has shifted, and the goals and definitions of success for items under evaluation—everything from programs and projects, to employee performance reviews, to student grades—may need to shift as well. Evaluating the extent to which goals have been achieved is a crucial aspect of growth and accountability, but it is a challenge figuring out how to accurately evaluate outcomes when the initial rubric assumed, for example, open offices and schools, in-person meetings, and physical resources. As we have been conducting evaluation work at Ithaka S+R for a number of programs and initiatives—like the Andrew W. Mellon Fellowship for Diversity, Inclusion & Cultural Heritage at the Rare Book School, the Citi Foundation Internship Program at the Brooklyn Museum, and the Aspen Presidential Fellowship—we have grappled with this challenge and have developed four principles to help guide our thinking.

#1 Reflect on whether redefining goals and measures of success is merited

When evaluating whether outcomes were successful, it is helpful to identify how the inputs that produce those outcomes may have been impacted by COVID-19 and its consequences. For example, in the case of evaluating a course, program, or fellowship, were any activities that were mapped specifically to an intended outcome affected by the pandemic? Was an in-person intervention designed to increase understanding of a topic but the activity was ultimately cancelled because of COVID-19? If the activity was not replaced, it is likely that students or participants did not increase their understanding of said topic, not because the intervention was unsuccessful, but because it never took place. In instances where activities were cancelled or substantially changed, it may make more sense to redefine goals. What activities did take place and in what format were they rolled out to participants?

Based on which activities did occur, what would a successful outcome look like? Perhaps the in-person activity was cancelled but replaced with a virtual activity that was able to cover some of the material. How might this change what the expectations for success should be? Or, for a program that adjusted or suspended many of its activities, perhaps a measure of success is that those changes themselves were communicated quickly and clearly with participants. In some instances, where large components of a course or program were cancelled, it may even make sense to suspend evaluation altogether.

#2 Review the evaluative research methodology(ies) and adjust as needed

Consider whether the data collection methodology and tools that were initially planned still make sense. For example, in-person focus groups are a common way to gather evaluative data to help determine the success of a program or project. Due to the pandemic, it may not be feasible to execute this plan and conduct the in-person conversations; instead, changing or adapting the methodology could be a better course of action. It may be as simple as holding a virtual focus group instead of an in-person one, but this depends on the participants involved. If participants have dispersed geographically because of COVID-19 and are now across time zones, meeting synchronously online might be too challenging. Or, perhaps some participants do not have easy access to technology or have a more complicated schedule now than prior to the pandemic. In situations like this, a one-on-one interview over the phone may be a good substitution for an in-person focus group.

In addition, reviewing the data collection tools themselves is a prudent step. Consider the time commitment being required or asked of individuals in the program to participate in the evaluative research. For example, perhaps a 30 minute survey or a one hour interview was reasonable prior to the pandemic, but is no longer realistic as many people have less time now than before. Ask if there are any questions in the survey or interview scripts that can be cut or condensed. Can the instrument be shortened so that it’s a 15 minute survey or a 30 minute interview?

In instances where goals have shifted, instruments should be updated to be responsive to new goals and forms of success. And importantly, the impact of the pandemic should be reflected in the evaluation. The instrument should acknowledge in some way what the past year has entailed and the impact on the program as well as participants. This helps tailor the evaluation to the present situation and is a good rule of thumb for not just for programs and courses, but for employee reviews and student grades as well.

#3 Think carefully about the demographics of the individuals or group under evaluation

Many people are struggling right now due to a range of issues that threaten their physical and mental health; this includes increased stress, rapidly fluctuating demands on time, balancing work and home, financial challenges, grief, and health challenges for themselves or loved ones. Much of this is a result of the pandemic, but it is also crucial to note that numerous communities are facing additional traumas as well. The murder of George Floyd, subsequent movements for racial justice led by Black Lives Matter activists, and attacks on Asian-Americans have increased public consiousness around issues of diversity, equity, inclusion, and access (DEIA). And a fraught election leading to the January 6th attack on the Capitol Building shook a politically divided nation.

The stress and trauma from these events, in addition to the pandemic, are being felt across the United States, but they are not felt proportionately. This is why an important step in conducting an effective evaluation should include consideration of the demographics of the individuals or groups being evaluated. For example, people who are low-income, BIPOC, women, or caregivers all may be shouldering disproportionate burdens that make it that much more challenging to participate in activities or meet deadlines. People from low-income backgrounds have faced inordinate job losses and economic impact, which has led to increased food and housing insecurity, making it more difficult to prioritize less immediate obligations. People of color are contracting COVID-19 at higher rates than people who are white in the United States, and are disproportionately joining or being pulled onto DEIA committees and initiatives, requiring vast expenditures of time and emotional labor. Women and caregivers have borne the brunt of home responsibilities in the shift to largely remote work and schooling, leading to lost work time and productivity. And these identities are not discrete; it’s worth noting that a single individual could fall into all three of these demographic categories, among others.

These uneven burdens should be considered or acknowledged in the evaluation process. To conduct an evaluation of, for example, a group of women and caregivers without acknowledging the particular hardships faced by this population during the pandemic not only runs the risk of being inaccurate in its assessment of success, it runs the risk of breaking trust with those individuals under evaluation. A failure to acknowledge that the tempo of life has shifted—and with it a rapid reorganization of time, responsibilities, and hardship—can be felt as an erasure of experience that damages the relationship between evaluator and evaluatee. Conversely, consciously acknowledging the pandemic’s unique impact on particular demographics, and allowing these considerations to be folded into the evaluation process can be an act of validation and support that builds trust, which is particularly important for long-term relationships.

#4 Contemplate the most effective ways to analyze the data and report the findings

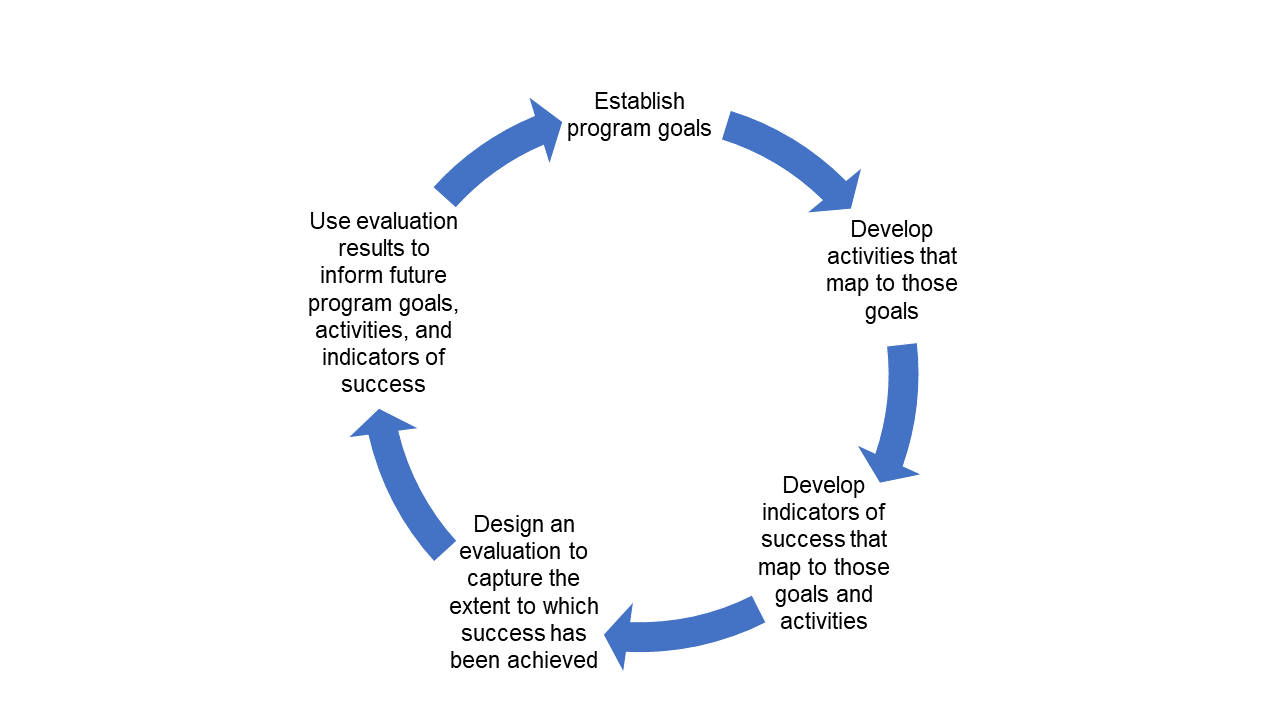

As with the principles listed above, when it comes time to analyze the collected evaluation data, it is paramount to contextualize the findings in a way that recognizes what the last year has entailed. This contextualization can help make sense of surprising findings and create a meaningful narrative for decision makers and funders. Particularly in the case of evaluative research that set a baseline prior to the pandemic, findings may look differently than previously imagined. Results might not be as positive as they would have been had the pandemic not taken place, and this might be a reflection of the external environment rather than the program or person themselves. For example, participants may have less positive responses to attitudinal questions in a second survey or interview conducted during the pandemic than they did when the baseline instrument collected data because of external factors influencing their perceptions. One way to understand whether a negative finding is a result of what is under evaluation or a result of the larger environment is to determine what was in the program or person’s control versus what was not. This is especially important because the results of the current evaluation can help inform what the next evaluation looks like (see Figure). Ideally, evaluation results help determine program goals, which impact program activities, and, ultimately, indicators for the next evaluation.

When reporting findings to funders and decision makers, including possible explanations for unexpected outcomes can help them understand the findings. This is important as it assists in identifying where making changes might lead to improved outcomes in the future and where making changes may not be effective. Qualitative data from individuals under evaluation can be especially helpful in explaining outcomes. Reporting should tie together factors influencing the evaluation and communicate a clear narrative to the recipient. Asking key questions, such as the ones below, and sharing the answers with leadership and funders can provide context that creates meaning from disparate data points.

- What were the external factors that impacted success?

- How were activities adapted or adjusted due to the pandemic?

- What impact did the pandemic have on the individuals involved?

- How do demographics factor into the findings, if at all?

Final Thoughts

As illustrated by these principles, it is crucial to be flexible and provide latitude when conducting evaluative research during a pandemic. Holding a person or program accountable to standards set in a different context without deviation is likely too rigid a strategy to provide a constructive evaluation for the present context. By providing flexibility around goals, research methodology, instruments, and reporting, evaluative research can respond to the radical shifts that have taken place in the world. Effective evaluation helps identify where to invest resources and improve outcomes, offering guidance in the midst of uncertainty—this is needed today more than ever. By recognizing change, rather than ignoring it, evaluative research can be a supportive and constructive mechanism for institutions and organizations striving to navigate the consequences of the pandemic.