Internship Program Evaluation

Brooklyn Museum and Citi Foundation

Foreword

Creating meaningful demographic change in the cultural sector has been a persistent challenge for institutions and national foundations. During a site visit to the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) in 2017, Ithaka S+R was invited to interview the director of the neighboring Charles Wright Museum, a museum of African American history, with which DIA had recently established a partnership. When we began the interview, the director Juanita Moore opened the conversation by asking, “So the foundations care about diversity again?” Her tone was amused and skeptical. Inviting her to say more, we learned that over her several decades in the field she had experienced multiple cycles of philanthropic interest in the topic of demographic representation in the cultural sector. The lack of diversity in the field still has not been addressed, and these scattered interventions, she feared, did not seem to make a difference.

Two months later at Spelman College Museum, the museum’s director, Andrea Barnwell Brownlee expressed these same sentiments in an unsolicited echo: “You can do it right, or you can do it again. We’ve been having [the diversity] conversation in the field for a long time. We’ve chosen to do it again.”

What does it mean to do it right, such that, for instance, when the population of the United States is majority people of color (POC) in 2045,[1] those responsible for the cultural narratives of our society are more reflective of it than the current cohort of museum executives, which in 2018 were 88 percent white?[2]

Some foundations have determined that the best way to effect change in this area is to create opportunities for emerging professionals from diverse backgrounds. The expectation of “paying your dues” to enter the field through unpaid internships disproportionately advantages the affluent. There have been some meaningful investments over the years that aim to address this question, such as Getty’s Marrow Undergraduate Internship Program, a number of the 2018 Ford/Walton grants, the Association of Art Museum Director’s paid internship program for college students from underrepresented communities, as well as The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation’s investment in Spelman College’s curatorial studies program.[3] Each of these programs recognizes that increasing diversity in the field is a decades-long process and results from meaningful interventions at the individual level.

This evaluation will analyze one such effort.

The Citi Foundation Internship Program: Brooklyn Museum

Citigroup and the Citi Foundation have supported two years of paid internships through the Brooklyn Museum’s education department. The $125,000 grant is part of the foundation’s “Pathways to Progress” initiative.[4] In 2017, Citi Foundation committed $100 million to this global effort to support pathways into careers for emerging professionals.

The funding allowed the Brooklyn Museum to hire twenty interns, ten for the summer of 2018 and ten for the summer of 2019. The goal for this funding was to provide paid internship opportunities to a diverse group of undergraduates who were considering careers in the cultural sector.

The evaluation sought to measure two key factors: 1) whether the museum was able to attract diverse cohorts, and 2) whether the museum was able to introduce these undergraduates to museum work in an inclusive way. In terms of racial/ethnic and socioeconomic demographics, the intern population was highly diverse. Evidence from exit surveys and interviews clearly reveals that the interns were in fact surprised by the level of support and inclusion they experienced at the museum. In this sense, while there is much more to examine and report on in this program, the fundamental criteria for success have been met. Key findings, which will be explored in the body of this report, are highlighted below.

Key Findings

Imposter vs. Belonging: This program created a welcoming environment which alleviated the sense of intimidation that the historic Beaux Arts encyclopedic museum can often evoke.

Compensating Labor: Compensation was critical in enabling most of the interns to participate.

Looking Behind the Curtain: Exposure to museum processes made cultural work familiar, revealing the variety of labor involved in running a cultural organization and maintaining a collection.

Networking and Professional Development: Creating opportunities for networking and professional development are crucial in this career stage.

Methods

In order to conduct the evaluation of this program, Ithaka S+R gathered evidence through multiple instruments. Interns were invited to participate in an entry survey, which gauged:

- Their exposure to the arts

- Their expectations and concerns about pursuing a career in the arts

- Their hopes about what they might gain from the internship experience

- The significance of being paid for their work

The entry survey also gathered demographic data about the interns, including:

- Race/ethnicity

- Gender

- Disability status

- Sexual identity

- Socioeconomic status

- Religion

Interns were also asked to complete an exit survey. The exit survey measured:

- Their impressions of the internship program

- Their interest in pursuing a career in the field

- Their advice for how to improve the program

- Their observations from working in a museum

The evidence gathered from these two instruments provides insights into the changing perspectives of the interns over the course of the program.

In addition, Ithaka S+R conducted observations of the interns’ engagement during Tuesday Programs and Brown Bag sessions and also conducted exit interviews to gain more insight into the interns’ experiences in the program and expectations for the future.

Demographics and Recruiting

It was important to both the Brooklyn Museum and Citi Foundation that this internship program be a driver of diversity in the field for emerging professionals. The following section evaluates the outcomes of the museum’s efforts.

Racial/Ethnic Composition of the Art Museum Field

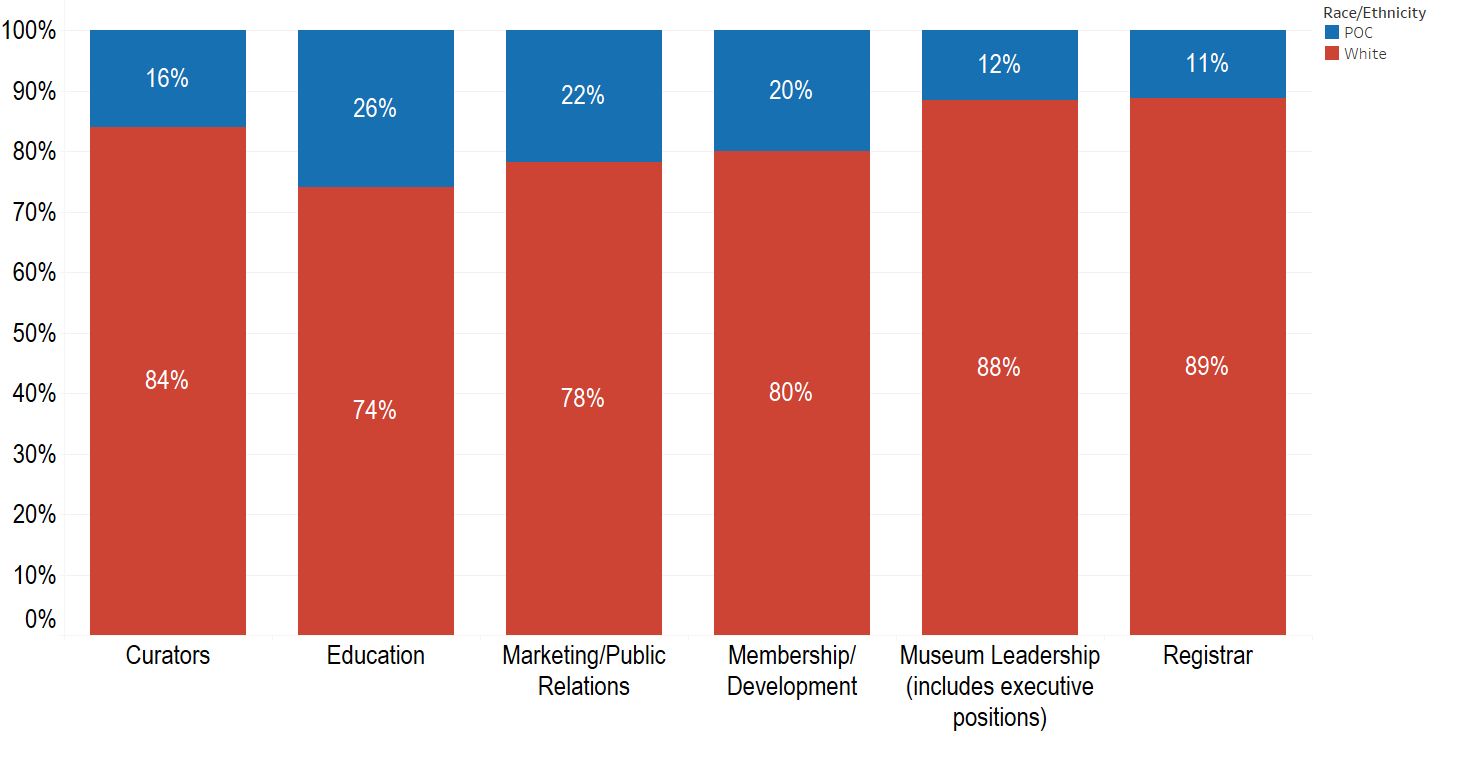

In 2018, Ithaka S+R collected demographic data from 332 American art museums. This was a follow up study to one conducted in 2015, and it showed that some progress has been made towards diversifying the field in certain ways.[5] However, many of the roles most integral to the intellectual operations of the museum remain overwhelmingly staffed with white non-Hispanic employees. Take, for instance, the departments where Citi Interns were placed for their assignments: Curatorial, Education, Marketing, Development, Museum Leadership, and Registrar. Figure 1 shows the percentage of white and POC staff in each of those departments, representing a total population of roughly 5,100.

Figure 1: Departments by POC and White staff

At the national level, at least three quarters of these positions are between 80 and 90 percent white. In some cases, the low number of POC staff in these categories means that professional development efforts can have quite a significant national impact. In 2018, fewer than one hundred museum executives identified as POC (inclusive of all C-level positions), and there were only 53 POCs in the registrar role. This is to say, in many of these categories, what can seem like minor advances may in fact yield a significant level of diversification relative to the status quo.

Composition of Internship Program

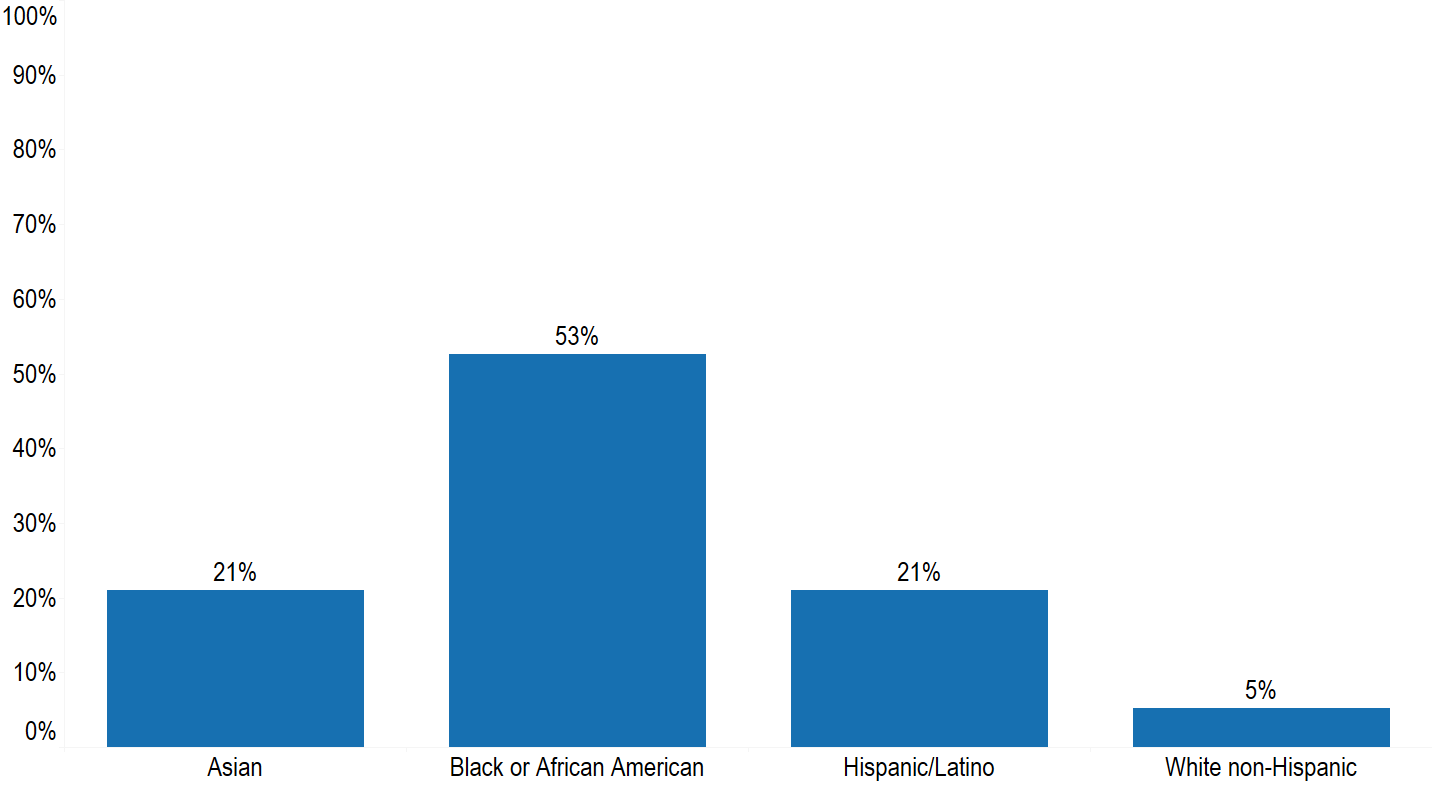

It is encouraging to analyze the demographics of the first two cohorts of Brooklyn Museum interns. Figure 2 shows the breakdown by Race/Ethnicity for the survey respondents.

Figure 2: Race/Ethnicity

Half of the interns were African American, one fifth were Asian, and one fifth were Hispanic/Latino. Compare this to data gathered from the 2018 demographic survey, which showed that, of a population of 545 interns who had reported their race/ethnicity, over 60 percent were white non-Hispanic.

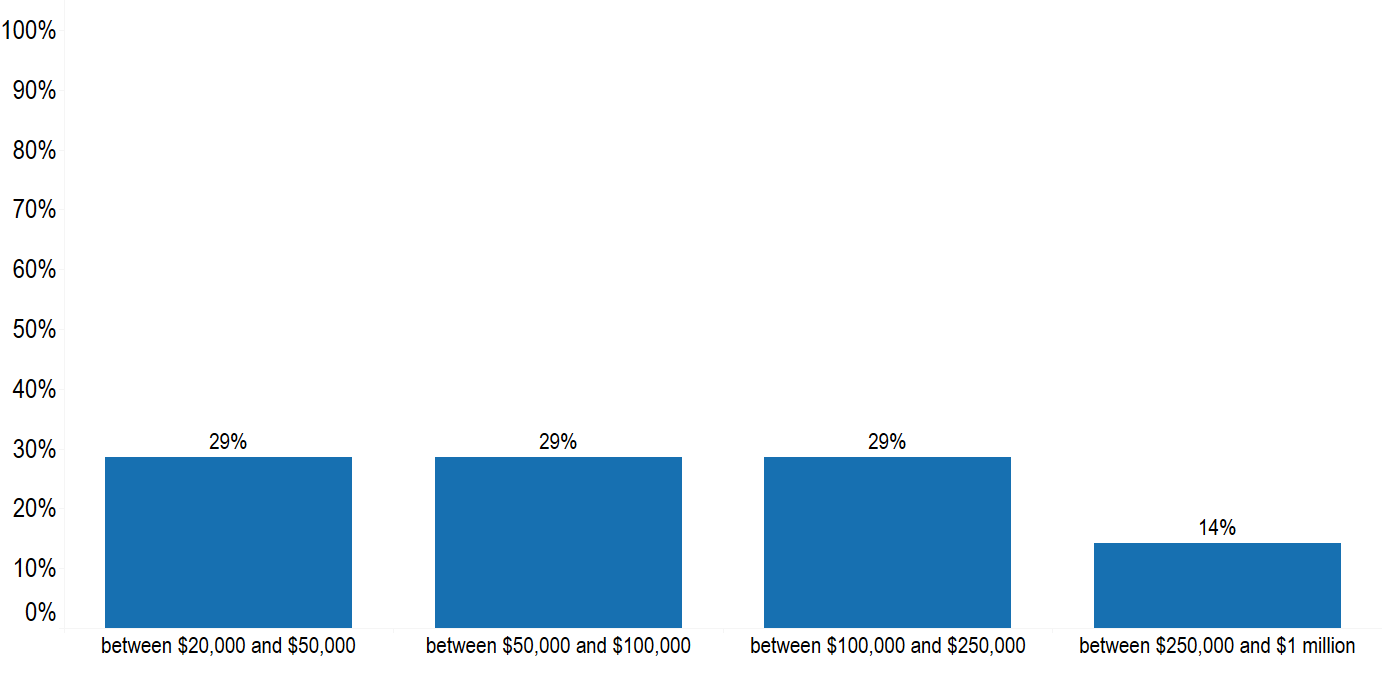

We were also able to measure socioeconomic demographics among the interns.[6] Grouping responses to preserve anonymity, Figure 3 shows that the two intern cohorts were highly diverse in terms of socioeconomic class.

Figure 3: Family Income

In terms of gender, 100 percent identified as women. As Ithaka S+R reported in our case study, “Small But Mighty: Spelman College Museum,” diversity at the intersection of gender and race is often overlooked and is an important component of qualifying a broad variety of perspectives for work in the cultural sector.[7] However, museum staff found that the application pool, while highly diverse across race and ethnicity, was not highly diverse by gender. This aligns with 2018 hiring patterns in the art museum field, where we found that 70 percent of hires born after 1990 identify as women.

The recruiting strategy relied primarily on outreach to CUNY schools, Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) and First Nations colleges.[8] A number of interns were also placed in the program through the NYC Youth Development program as part of the Neighborhood Development Initiative.

Program Description

This section will first explain the structure of the internship program and then provide findings from the interns’ responses to interviews and survey questions. These will inform observations and recommendations about the program structure and internship experience.

Structure

The Citi Foundation Internship Program was designed primarily by Monica Marino, adult learning manager in the education department of the Brooklyn Museum. It was modeled after the Museum Seminar Internship Program (MuSe) an internship program she administered at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The internship program fits into a suite of professional development programs offered through the museum’s education department, including teen programs, arts education programs, and a postgraduate fellowship program. Through these programs, the museum creates opportunities to engage in the labor of producing cultural programming for high school students, undergraduates, postgraduates, and graduate students. The Citi Internship program more than doubled the capacity for the museum to engage undergraduate students.

The Citi internship program included several components:

- Departmental Assignments

- Tuesday Programming

- Brown Bag Lunches

- Formal Mentorships

The interns’ departmental assignments involved about four days of full time work on site at the museum. Each museum department submitted a request for an intern to the education department in order to aid the selection process and ensure that interns would develop hands-on experience in the institution. Marino reflected that these extended projects were critical for the interns to gain meaningful experience, something substantial that could be shared on a resume: “Having a departmental placement for the full ten weeks is important, instead of doing two weeks in each department. It allows the interns to have a deeper experience and complete a full project.”

On Tuesdays, Erika Lively, Internship Advisor, would lead the group in a day of programming. This was an opportunity for the interns to come together as a cohort and also gain exposure to the operations of both the Brooklyn Museum and many other cultural organizations in New York. Marino sees the value of Tuesday programming as adding a degree of breadth to the internship experience: “Tuesday programming comes into play in exposing interns to other areas of the museum, and to other institutions. With that exposure they can decide whether they want to pursue these other areas or not.”

Brown Bag lunches were held weekly and were an opportunity for interns to present to one another on their work or other topics of interest. It served as another chance for interns to spend time together as a cohort. At the end of the program, each intern was paired with a mentor. These mentors have agreed to contribute their time and experience to guide the interns in their career paths.

Each year of the program had a thematic focus. Year one focused on the intersection of libraries, archives, and museums. Drawing on lessons learned from the development of the exhibition, We Wanted a Revolution (2017), readings and discussions focused on issues of representation and legacy in the construction of archives—whose voices and experiences are preserved? Year two’s thematic focus was on the responsive museum—in times of political division and organized calls for social accountability, how can museums engage in these discourses with respect, humility, and care?

Marino shared that the museum has been lucky to extend some of the opportunities afforded the Citi Interns to other undergraduate interns at the museum. Tuesday programs and Brown Bag lunches are inclusive of everyone engaged in departmental internships. While some of those interns remain unpaid, this practice has helped to prevent a sense of division among interns at the museum. As Marino said, “When I was running the college and grad program at the Met, there was a huge distinction between paid interns and unpaid interns. The paid had a full program designed for them, whereas the unpaid interns could only attend some, and were often left out of those opportunities. It’s important to use resources to provide these opportunities to everyone.” Because staffing, transportation, and program administration are already built into the Citi Internship budget, there is no increased expense to include all interns in these events.

Intern Experiences

The museum was highly successful in recruiting diverse interns. But it was equally important to craft a productive and inclusive experience for these students. In Ithaka S+R’s earlier case study of the Studio Museum, one staff member shared their perspective that diversity efforts in the 1970s and 1990s failed because of the blind pursuit of demographics.[9] Focusing on demographic diversity without cultivating an inclusive and equitable work climate can lead to alienating experiences that actually reinforce the inaccessibility of cultural institutions.

The following sections share evidence and analysis of the Brooklyn Museum’s climate, and the experiences of the two cohorts of interns. These observations are organized around issues of inclusion, compensation, experience, and professional growth.

Imposter vs. Belonging

In the entry survey, interns were asked if they had reservations in pursuing a career in museums. Some expressed concerns that cultural institutions were exclusionary on the basis of race and class and that this made them apprehensive about pursuing a career in the field. From comments in the exit survey, it was clear that interns were pleasantly surprised to find not only that the museum was a welcoming and inclusive environment, but also that museum staff engaged deeply in critiquing their own institution and had a proven track record of engaging positively with their local communities.

This appreciation spanned collections, programming, and staffing issues. As one intern wrote, “The canon isn’t right, and Brooklyn Museum addresses that directly. What attracts people to working at the Brooklyn Museum, is that you feel uncomfortable with the atmosphere of cultural institutions in general, and you are looking for a place that will address it directly. Brooklyn Museum is that place. The way they present art, the way they organize it, makes it clear. But also the people there make it clear.”

Another intern wrote in the exit survey that she was very impressed with the program: “It didn’t feel like an internship, it felt like everybody was trying to pull you up. Typically, interns are treated as inconsequential, but here everybody had time for you, every day we learned something new. People were very direct. Not at all what I expected. People here were very open. It was such a relief.”

Another intern compared the summer program to her previous internship: “Last summer I had an unpaid internship and I wasn’t doing anything during it. Here, I felt like I was doing something. I felt like we were valued by the museum.” This evidence, along with similar feedback from others, suggests that the project-based ten-week departmental assignment resulted in valuable and meaningful experiences for the interns, while also allowing for a specific and discrete amount of work to be completed for the department.

Another intern wrote that spending time with the cohort was the best part of the program: “They did a really good job at selecting interns. Such a diverse and interesting group. The level of engagement and intelligence was so high but without feeling inaccessible. It never felt like I was excluded from conversation with staff.” The cohesiveness of the cohort suggests an opportunity to structure alumni networks through the internship program, which could strengthen possibilities for job placement and career growth.

Some interns shared that the museum was very patient and inclusive in terms of meeting the interns where they were regarding knowledge of art history and museum operations. One intern noted, “I am glad I took on this opportunity. Many conversations went over my head because I had no art background but my supervisors and other fellows were very helpful in teaching me what I didn’t understand. I always enjoyed the brown bag lunches because it was interesting to see what my peers were working on in their departments.”

That a number of interns expected that cultural institutions could be exclusionary spaces aligns with perspectives of cultural consumers based on La Placa Cohen’s survey Culture Track.[10] That the Brooklyn Museum was able to overcome these expectations and create an inclusive environment where learning and growing professional connections naturally developed speaks to the diligent efforts of museum staff.

Compensating Labor

As one indication of the high level of competition for entry-level positions across the field, particularly in New York, 600 students submitted applications for the ten internship openings in 2019. Cash-strapped museums are often drawn towards hiring unpaid interns to cut costs.[11] The legality of this practice in the for-profit sector was clarified in the case Glatt vs. Fox Searchlight, which created a new test to govern labor law as it applies to unpaid interns.[12] Since that finding, legal questions have been raised concerning its application to nonprofit organizations.[13] The Association of Art Museum Directors has been outspoken in support of museums moving towards paid internship models, and has recently begun a program that facilitates ten paid internships at ten art museums across the country. Director Chris Anagnos framed AAMD’s commitment to this initiative: “Providing paid summer internships to students is an important step in addressing the persistent limitations on access to job-related experience, and particularly the disproportionate effect these limitations have on people of Asian, Black, Hispanic, Native American, or multiracial backgrounds. Supporting a diverse pipeline of people entering the field will enrich and enliven the next generation of art museum professionals.”[14]

With the Citi Foundation funding, interns were paid $15 per hour for 35 hours of work per week over the summer. When asked whether compensation was a necessary criterion to accept the internship, one intern said, “I only searched for and applied to internships that were paid positions. I believe that my time and value as an intern is worth monetary compensation.” Some interns indicated that they would not have been able to rely on family support to finance the summer in New York and would not have been able to accept an unpaid position.

One of the important ways in which compensation makes cultural work available to historically excluded audiences is through addressing geographic barriers. The cost of establishing a temporary residence in New York for a summer is seen by many as too burdensome without some form of compensation. As one intern said, “If I wasn’t getting paid I would not have been able to accept being the distance from home.” Another shared the following:

“I am from [the South] and so a non-paid internship would not have been feasible due to the heavy costs of living in New York. I do not have much family in New York, so much of housing and transportation costs would have fallen on me. A paid internship also provides incentives to work hard, because I always strive to do work to my best ability and plus it is a tremendous help to personal costs in New York.”

When considering the question of diversifying the cultural sector, it is crucial to understand the barriers to entry and how they affect populations differently. This highly diverse group of museum professionals, two of whom have since secured employment in the Brooklyn Museum, have clearly indicated that compensation was essential for their participation in the program.

Looking Behind the Curtain

One of the most valuable aspects of the museum internship is the exposure to museum operations, which illuminates not only the variety of possible career trajectories, but also serves to demystify the processes that lead to the production and preservation of visual culture.

Many interns expressed surprise at the end of the program at the amount of knowledge and experience they gained over the summer. “I just thought I’d sit at a little desk and be given an assignment,” one intern explained in an exit interview. Another intern mused about learning how to communicate with donors, describing the balance of friendliness and professionalism as akin to the prose of a Victorian novel. Another intern in the education department was similarly impressed with how much she learned, “I love the education department. It’s a community, everyone helping everyone, teaching and learning. Through education, I got to see a lot of behind the scenes operations. I got to experience teaching classes and learning from other instructors.” An intern in the registrarial department was impressed by how many different departments in the museum she was able to interact with in her role: “I learned in the registrar’s department about all kinds of interactions in the museum, about how connected and multifaceted it is. They really keep the exhibitions and artwork going. I respected that. I thought it was just going to be cubicle work, but I was helping with packing and so on, and I was seeing how other departments operated and how they all worked together.”

For many of the interns, this was the first time they had the opportunity to observe the labor involved in running such an institution. In some cases, praise for this experience was effusive: “It was an overall excellent experience. I got a lot out of my summer. At the Brooklyn Museum, I felt like I was being productive and that my contributions in my department mattered. The Tuesday programming exposed me to so many more career options that I didn’t even know existed. I know that any success I have in the future can be attributed to my time at the Brooklyn Museum.”

Some of the interns felt that there was an uneven level of interest within the cohort, and wished that more care had been taken to ensure that each intern had a deep commitment to art history and cultural production. As one put it, “With all due respect, some interns felt as if they did not want to be here. For a museum internship, it would be best to have interns who have some interest in art and are willing to learn. It is unfair to know that someone who applied and who really has an interest in the arts wasn’t able to partake in this wonderful internship.” Including graduate students in future internship cohorts may be one way to address this concern.

In an academic context, Marino has seen the value of diversifying the level of experience, something she hopes to bring to future iterations of the internship program. In addition to her role as adult learning manager at the Brooklyn Museum, Marino is also a visiting instructor at Pratt Institute. She teaches two museum education courses, contemporary museum education and innovation and collaboration in museum education. Unlike the traditional structure of higher education coursework, Marino’s classes include both graduate and undergraduate students. In her experience, the exchange between these groups is mutually beneficial: “Having graduate and undergraduate students learning together provides an opportunity for both. Graduate students will often take on a leadership role in the classroom, which can help to prepare them for teaching and presenting to their peers. They structure the conversation in a way that elevates discourse for the undergraduates. It also allows the undergraduates to see what the next steps might be in their academic trajectory.” Marino sees a similar opportunity in expanding the scope of the internship to include graduate students. “Having graduate students as well as undergraduates in the internship could provide similar benefits, raising the ceiling for discourse across the cohort, as well as providing a model for the next step in the career path for those interested in pursuing cultural work.”

Many interns expressed that the Tuesday programming was a highly taxing part of the week. In year one, programming consisted of a series of off-site visits, typically two or three over the course of the day. They were organized such that staff at the participating institution would present to the students about topics relevant to their work or provide tours of their collections and exhibitions. Some interns felt it was difficult to keep up with the amount of travel and volume of programming. Others thought it would be better to have more opportunities to learn about the Brooklyn Museum as a cohort. Based on this feedback, the internship administrators focused the second year of Tuesday programs internally, increasing the number of curator talks, spending more time with the library and archive, as well as with collection storage and preservation. Museum staff are in agreement that blending these two approaches in the future would be ideal, maximizing the breadth and depth of the interns’ exposure to the Brooklyn Museum as well as other New York City cultural institutions.

Networking and Professional Development

One of the benefits of the Tuesday programming is that it facilitated a high number of connections between the interns and professionals in the cultural sector in a relatively limited amount of time. Network development was a deliberate facet of the program structure, not only through the Tuesday programming, but also through the mentorships that are formally established by the end of the summer. Each intern identifies a mentor, within the Brooklyn Museum or at other organizations. A set of check-ins are scheduled after the conclusion of the internship in order to set expectations about the degree of commitment required from both parties. While it is too soon to assess the impact of these relationships, there is value in having a formalized point of contact for the students as they return to their undergraduate studies.

These networking opportunities were coupled with a robust professional development workshop in the first year of the program. Toward the end of the summer, Kate Lupo, then executive assistant to Anne Pasternak, offered to lead a workshop on job interviews. This was an unplanned development. Lupo has a consulting business in Los Angeles, where she coaches emerging professionals in how to successfully enter the media industry. The workshop began with high-level advice about securing work after college. She explained the value of a network (greater than your GPA) and gave some instruction in how to gracefully build the kinds of professional relationships that open doors. She then provided a set of guidelines, illustrating how to describe their experience and professional interests in an interview setting. At the end of the workshop, she conducted mock interviews with most of the interns, helping them to work through their nervousness and build up their confidence. Many interns praised this workshop in their exit interviews. One said, “I think the workshop needs to travel around the world. Interviewing skills are extremely important. Having Kate come and explain how to do it with expertise was really helpful. I would have liked to see something about resume building, which would help to actually get a job after or during college, and also something on helping to develop a portfolio that looks professional.”

The following year Lupo had moved on from the position, and as a result the 2019 program did not include this workshop.

Recommendations

The Citi Foundation internship program exceeded the expectations that have been established by traditional internship programs in the cultural sector. Interns had clarity around their work and completed a scoped project for the museum over the course of their ten weeks. They were paid an hourly wage. They participated in on- and off-site programming that both increased their exposure to cultural institutions and provided an opportunity for the interns to get to know one another. At the end of the program they were paired with mentors who will continue to catalyze their professional development.

Successful as the program was, with some minor adjustments it can have an even greater impact.

Restructure Tuesday Programs: There is value in both on- and off-site approaches to Tuesday programming. In future iterations, balance these programs in order to more effectively offer a depth of exposure to a single museum, while introducing a number of other New York cultural institutions to the interns. Set expectations with the interns that these will sometimes be tiring, but are well worth the amount of energy they require.

Emphasize professional development: Bring back and expand the interview workshop, and add a resume workshop. At this stage in their careers, such training is invaluable and was clearly well received by the 2018 cohort. Investing in such workshops will go a long way towards improving the students’ chances of securing work in the cultural sector, which is the ultimate goal of the program.

Create strong alumni networks: Interns appreciated the ability to learn together as a cohort and will continue to benefit from maintaining connections to their fellow interns as they graduate and enter the job market. Providing some form of alumni network development would strengthen the impact of the program by creating a support structure for those interested to enter the field. It would also crucially allow the museum to keep track of the alumni’s career trajectory, allowing them to measure the impact of the program over time.

Conclusion

How do students begin to conceptualize the prospect of working in an art museum? The initial stages are daunting, certainly. Competition for entry is high, while compensation in the field is typically very low, excluding the most senior positions. Applicants compete with graduates from the most elite schools in the country, who perhaps have gone into debt to finance connections that lead to entry-level positions, which often pay less than $40,000 per year. And if the target job requires a doctorate, the candidate is apt to spend six or more years with a low level of funding, trying to get prestigious internships, many of which are unpaid. Perhaps the student will supplement their income through an adjunct position at an exploitative rate of pay. Hopefully they do not have to, or hope to, support a family.

For people of color, these realities are compounded by the absence of others with similar backgrounds. For those from families of limited means, or whose family has avoided cultural institutions, viewing them as exclusive spaces that present primarily colonial and patriarchal cultural narratives and participate in a market economy they could never dream of having access to, there are understandably some substantial cognitive hurdles before even beginning to consider the financial implications of such a pursuit.

And this is compounded by the whiteness of most elite cultural institutions. Many of the interns in the Citi Program noted the potential problem of being the only POC on a museum’s curatorial staff and not feeling a sense of belonging.

In order for those expectations to be subverted, and to create the first step in a path for diverse emerging professionals to contribute toward the production and preservation of culture within public institutions, there are many individuals within and outside the Brooklyn Museum who have cooperated with thoughtfulness and generosity. Adjoa Jones de Almeida’s leadership as director of the education department, Monica Marino’s role in structuring and guiding the internship, and Erika Lively’s daily work administering the program reflect essential contributions. But there were also many professionals within the Brooklyn Museum, and in partnering museums who contributed their time and expertise to create a positive experience for these students. Without funding from the Citi Foundation, none of these efforts would have been possible. It is likely that a continuation or replication of this program will, over time, create pathways into the museum field for diverse emerging professionals in a way that can substantially change the demographic composition of the sector.

Endnotes

- William H. Frey, “The US Will Become ‘Minority White’ in 2045, Census Projects,” Brookings, September 10, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2018/03/14/the-us-will-become-minority-white-in-2045-census-projects/. ↑

- Mariët Westermann, Liam Sweeney, and Roger C. Schonfeld, “Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey 2018,” Ithaka S+R, 28 January 2019, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.310935. ↑

- For more information see: “Getty Marrow Undergraduate Internships: Students,” The Getty Foundation, https://www.getty.edu/foundation/initiatives/current/mui/mui_students.html; “Ford Foundation and Walton Family Foundation Launch $6 Million Effort to Diversify Art Museum Leadership,” The Ford Foundation, 28 November 2017, https://www.fordfoundation.org/the-latest/news/ford-foundation-and-walton-family-foundation-launch-6-million-effort-to-diversify-art-museum-leadership/; “AUC Art History + Curatorial Studies Collective,” Spelman College, https://www.spelman.edu/academics/majors-and-programs/art-and-visual-culture/aucartcollective; “AAMD Announces Paid Internship Program for College Students from Underrepresented Communities,” AAMD, 11 July 2018, https://aamd.org/for-the-media/press-release/aamd-announces-paid-internship-program-for-college-students-from. ↑

- For more information see “Pathways to Progress,” Citi, https://www.citigroup.com/citi/foundation/programs/pathways-to-progress.htm. ↑

- Mariët Westermann, Liam Sweeney, and Roger C. Schonfeld, “Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey 2018,” Ithaka S+R, 28 January 2019, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.310935. ↑

- Unfortunately, this cannot be benchmarked against the broader field. The 2015 and 2018 demographic surveys collected data directly from HR departments rather than individuals, ensuring a high participation rate, but limiting the demographic variables that could be collected to those present in HR records. See Roger Schonfeld and Mariët Westermann, with Liam Sweeney, The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey,” The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, 28 July 2015, https://mellon.org/media/filer_public/ba/99/ba99e53a-48d5-4038-80e1-66f9ba1c020e/awmf_museum_diversity_report_aamd_7-28-15.pdf, and Mariët Westermann, Liam Sweeney, and Roger C. Schonfeld, “Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey 2018,” Ithaka S+R, 28 January 2019, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.310935. ↑

- Liam Sweeney, “Small but Mighty: Spelman College Museum,” Ithaka S+R, 7 June 2018. https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.307535. ↑

- The CUNY System enrollment by Race/Ethnicity as of Fall 2018 are as follows: American Indian/Alaska Native: .03 percent; Asian/Pacific Islander: 21 percent; Black: 25 percent; Hispanic: 31 percent; White: 23 percent. See “Total Enrollment by Race/Ethnicity and College: Percentages Fall 2018,” CUNY Office of Institutional Research and Assessment, April 25, 2019, https://www.cuny.edu/irdatabook/rpts2_AY_current/ENRL_0015_RACE_TOT_PCT.rpt.pdf. ↑

- Roger Schonfeld and Liam Sweeney, “An Engine for Diversity: Studio Museum in Harlem,” Ithaka S+R, 23 January 2018. https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.306190. ↑

- LaPlaca Cohen, “Culture Track’17,” Culture Track (2017). ↑

- Jennifer Smith, “Budget Cuts Looming for Brooklyn Museum,” The Wall Street Journal, May 18, 2016, https://www.wsj.com/articles/budget-cuts-looming-for-brooklyn-museum-1463612954. ↑

- “In place of the DOL’s criteria, the court announced an alternative test governing unpaid internships: the “primary beneficiary” test. Under this test, an employment relationship is created when the “tangible and intangible benefits provided to the intern” are less “than the intern’s contribution to the employer’s operation.” The test, by the court’s estimation, has two central features: First, it focuses on what the intern obtained in exchange for his or her work. Second, it examines the “economic reality” between the two parties. To determine the primary beneficiary, the Second Circuit proposed a “non-exhaustive” list of factors directed at the extent to which the internship is structured to promote the intern’s education.” See “Glatt v. Fox Searchlight Pictures, Inc.,” Harvard Law Review, February 9, 2016, https://harvardlawreview.org/2016/02/glatt-v-fox-searchlight-pictures-inc/. ↑

- Thomas Johnson, “The ‘Fox Searchlight’ Signal: Why ‘Fox Searchlight’ Marks the Beginning of the End for Preferential Treatment of Unpaid Internships at Nonprofits,” Virginia Law Review 102, no. 4 (2016): 1127-162. www.jstor.org/stable/43923331. ↑

- “Paid College Internship Program Will Continue for Second Year, Engaging Students from Underrepresented Communities in Career Development in Art Museums,” Association of Art Museum Directors, accessed December 8, 2019, https://aamd.org/for-the-media/press-release/paid-college-internship-program-will-continue-for-second-year-engaging. ↑