Is AI Literacy the Trojan Horse to Information Literacy?

Insights from our AI Literacy Cohort Workshops

In April 2025, we launched the Integrating AI Literacy into the Curricula cohort project, in collaboration with librarians and educators at 45 colleges and universities, to conduct research on the current state of AI literacy and develop actionable pathways to providing effective AI literacy programming for students and faculty.

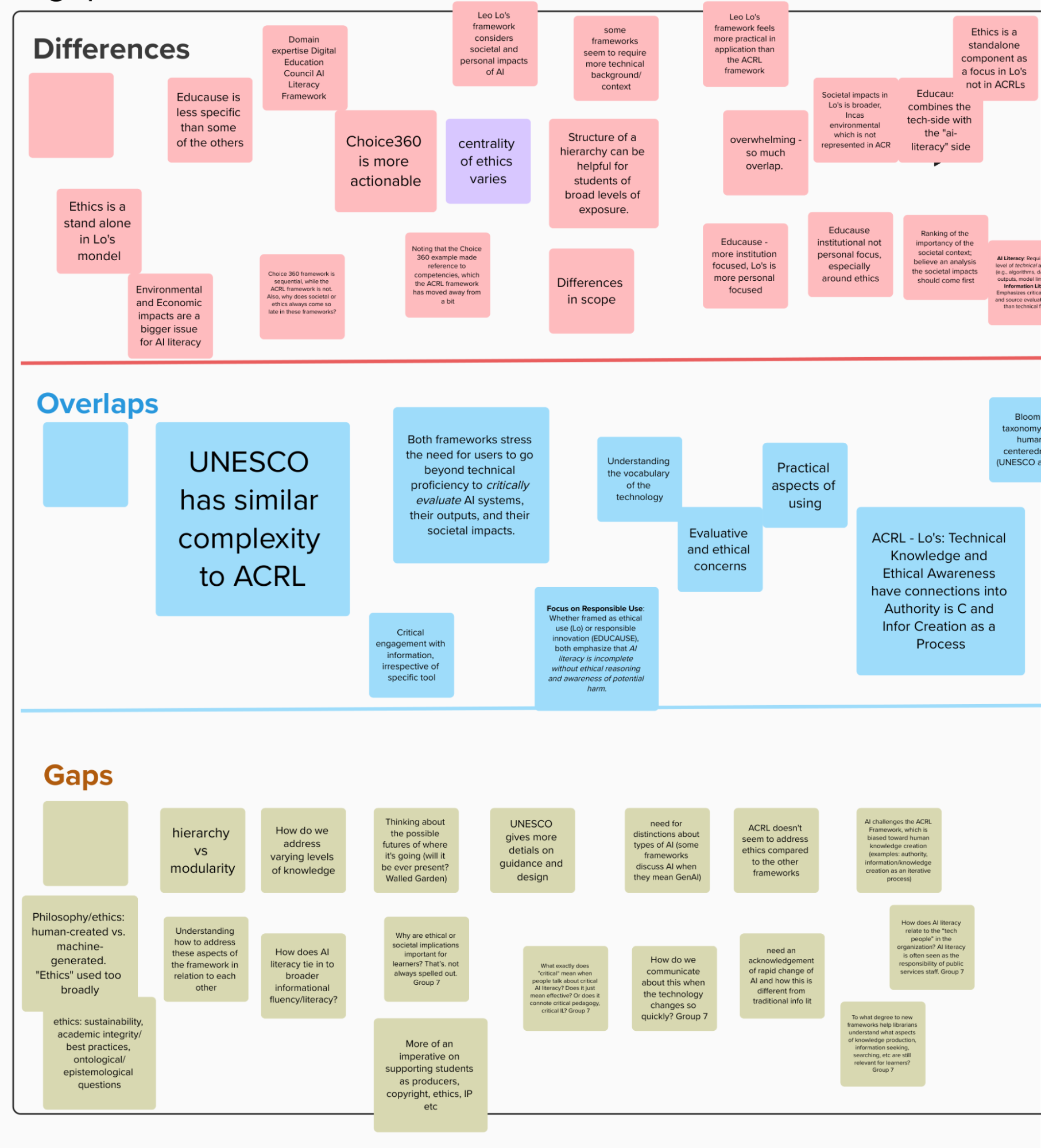

In mid-May, we held our first cohort workshops to start thinking through AI literacy using shared language. After reviewing the ACRL information literacy framework and existing AI literacy frameworks, participants engaged in two breakout sessions to dig deeper. Participants documented ideas in Mural to share with other cohort members.

In the first breakout session, participants compared existing AI literacy frameworks to the ACRL information literacy framework. These included:

- UNESCO AI Competency Framework for Students

- Choice 360 AI Literacy Framework

- Digital Education Council AI Literacy Framework

- Educause AI Literacy Framework for Higher Education

- AI Literacy: A Guide for Academic Libraries

Participants observed several key differences. First, the ACRL framework is more conceptual while other AI literacy frameworks like Choice 360 and Educause are more practical in nature. Second, the ACRL framework is modular with no definitive entry point while other AI literacy frameworks like UNESCO’s and the Digital Education Council’s are more hierarchical with a sequential structure. These differences lead to tangible disparities in implementation. While the ACRL framework might be adopted as higher-level conceptual guidance, the more practical AI frameworks are relatively more actionable and ready for curriculum integration.

One participant described AI literacy as “a bucket under the umbrella of information literacy,” and other participants noted that AI literacy is also driving changes to traditional information literacy. For example, the information literacy framework is biased towards humans as the information creator and AI challenges that assumption.

Participants pointed out that a number of differences exist even among the various AI literacy frameworks. For example, the UNESCO and Digital Education Council frameworks place humans at the center while other frameworks do not. Further, different AI frameworks seem to require different amounts of technical knowledge for engagement.

A fragment of the participants’ mural notes examining the differences, overlaps, and gaps in AI literacy frameworks as compared to ACRL’s information literacy framework. See the full size image.

Participants agreed that both the ACRL information framework and the AI literacy frameworks require critical engagement with information. This shared emphasis on critical thinking creates a bridge between traditional information literacy and emerging AI literacy. In turn, this overarching requirement leads to more specific needs for technical knowledge development and ethical awareness. Understanding how AI systems generate information reinforces that no source is inherently authoritative without context. Recognizing AI biases and limitations shows that all information reflects its creators’ perspectives and purposes. Users must actively evaluate rather than passively consume information, whether that information is from traditional sources or AI systems.

Participants noted a number of gaps in the frameworks. None include detailed guidance on how to address varying levels of knowledge. Moreover, the term “AI” now seems to be used exclusively to refer to generative AI, overlooking other types of AI entirely. Given the rapid pace of AI development, participants felt the need to acknowledge and communicate the quickly shifting landscape and understand how this is different from traditional information literacy. Some participants observed that the term “ethics” is used too broadly to encompass almost everything, including academic integrity, societal impacts, sustainability, copyright, and intellectual property, yet the intended audience of each of these ethical concerns is not clearly specified. For example, a participant questioned why the societal implications are important for learners.

Building on the insights from the first breakout session, participants moved to a second breakout session where they worked toward a working definition of AI literacy for a chosen persona. Continue to Part 2 to see how participants apply AI literacy to different demographics.

Ithaka S+R is organizing an additional cohort of this project that will launch in the fall. Several spots are still available. If you’re interested in participating, please contact Dylan Ruediger (dylan.ruediger@ithaka.org).