Applying AI Literacy to Student and Faculty Personas

Insights from our AI Literacy Cohort Workshops

This May, we hosted the first workshops for our Integrating AI Literacy in the Curricula cohort, a group of 45 colleges and universities committed to promoting AI literacy as a core learning outcome on their campuses. In the first half of the workshop, we facilitated a discussion of information literacy and AI literacy frameworks.

In the second breakout session, participants selected one of six provided personas and hypothesized about the risks, benefits, and needs of AI use for their chosen profile. The profiles included three students—an undergraduate, a graduate student, and an adult online learner—and three faculty members—a humanist, social scientist, and natural scientist. The faculty ranged from those seeking to upskill in AI to those concerned about academic integrity. Through this process, groups worked toward tailored definitions of AI literacy specific to different disciplines and demographics.

Two profiles, shared below, are useful illustrations of the exercise:

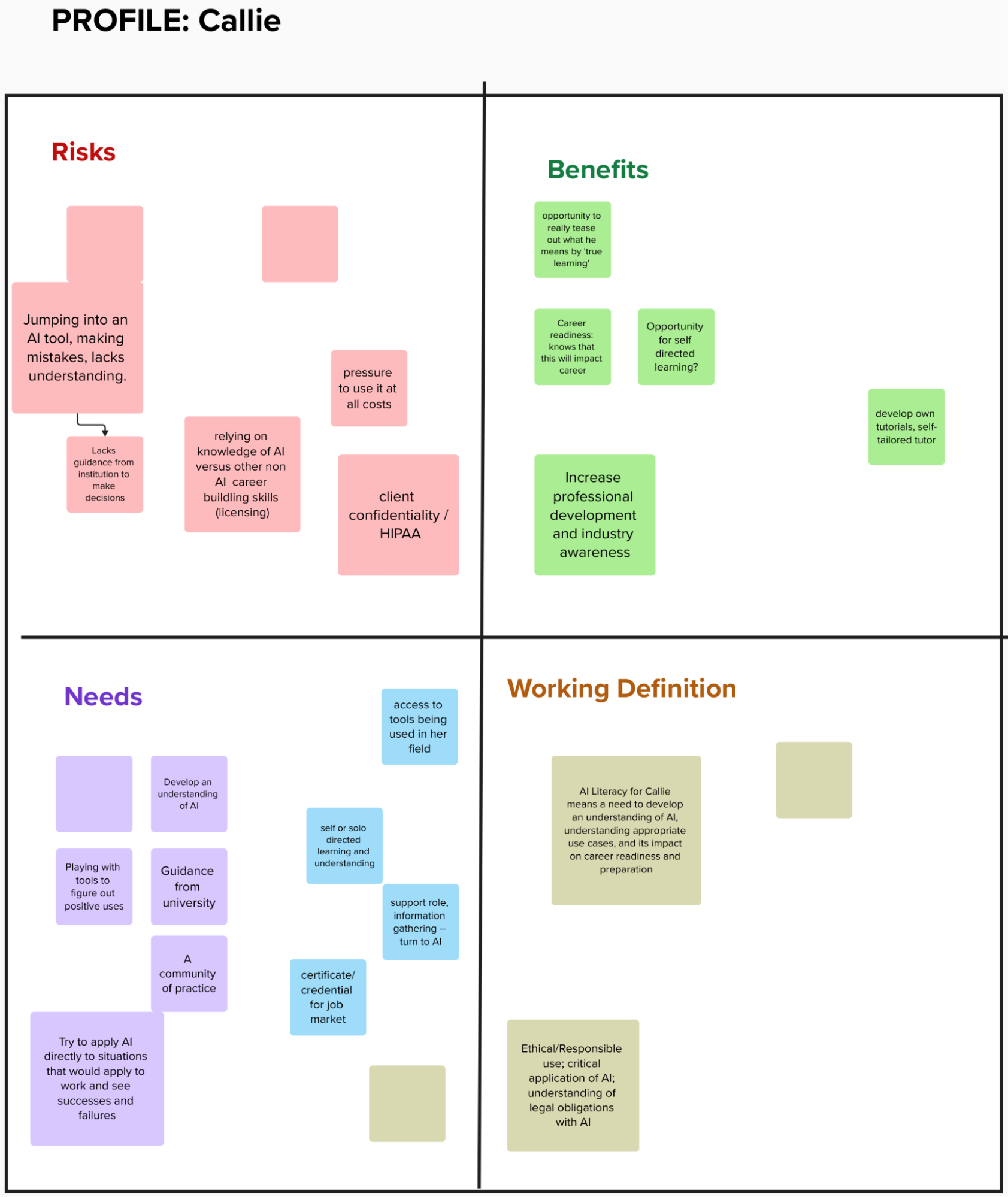

Callie is a 38-year-old working toward a degree in physical therapy through online classes. Given her online learning content and adult learner status, participants identified that Callie needs access to relevant AI tools in her field and the ability to identify positive use cases by experimenting with the tools herself or learning from her field’s community of practice.

Callie is concerned that she won’t be a competitive candidate if she doesn’t know how to use AI. This career anxiety led participants to note that she may need to obtain an AI certificate in her field to prepare for the job market, as the health industry is highly influenced by AI and using AI will benefit her career readiness.

However, participants also identified potential risks in Callie’s engagement with AI. As someone new to both the healthcare field and AI technology, Callie risks diving into AI without solid foundational understanding and might inadvertently violate client confidentiality or HIPAA regulations.

The working definition of AI literacy for Callie that emerged from these considerations states: “AI Literacy for Callie means a need to develop an understanding of AI, understanding appropriate use cases, and its impact on career readiness and preparation.”

Participants’ thoughts on the profile Callie, examining the risks, benefits, needs, and a working definition of AI literacy. See the full size image.

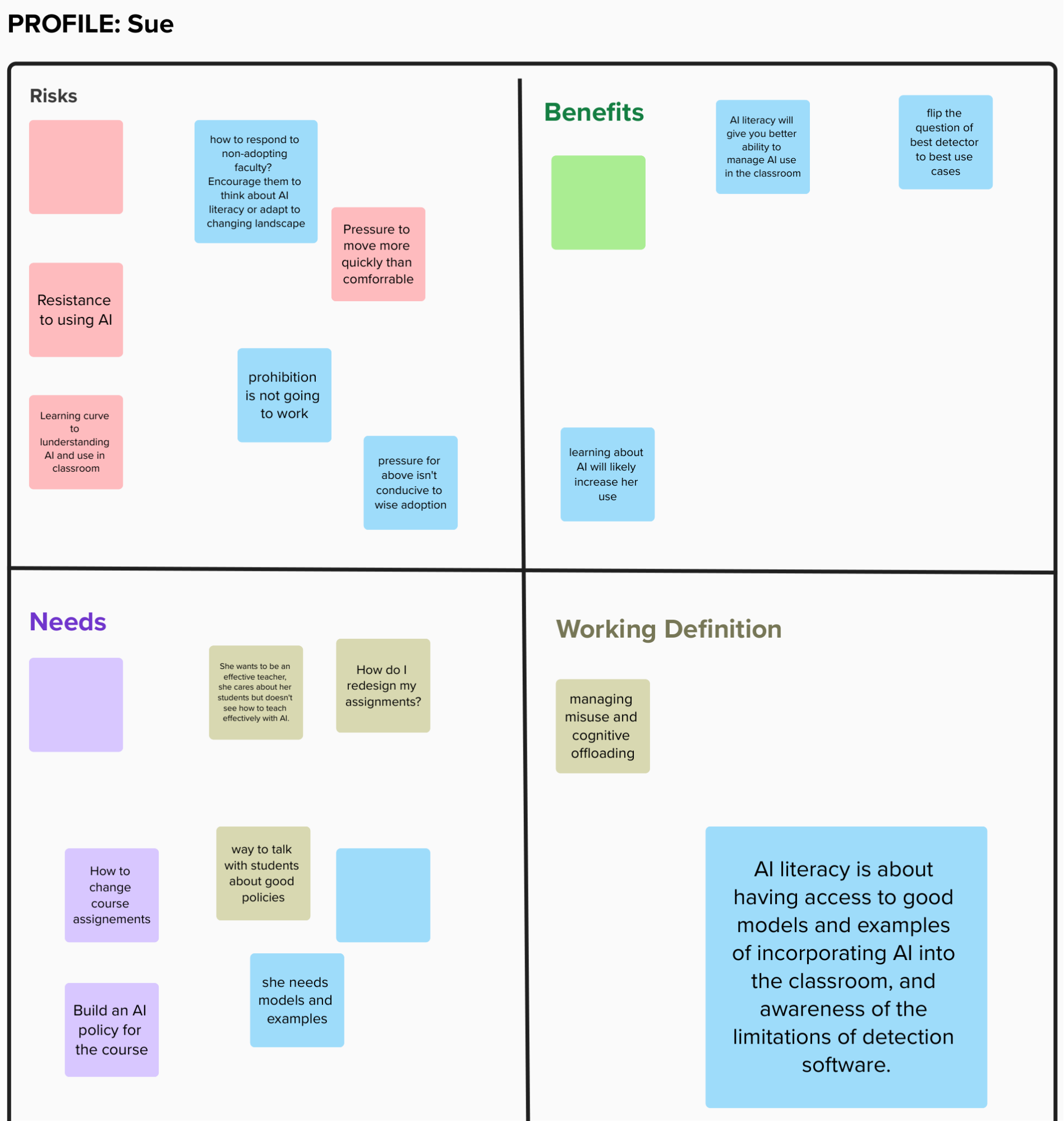

Sue is a sociology lecturer facing departmental pressure to promote student AI use. This institutional pressure creates risks for Sue, as participants noted she might be pushed to adopt AI faster than she feels comfortable. Sue is personally resistant to AI and wants to know what AI detector is the best for catching cheaters. However, participants pointed out that despite her strong concerns about students using AI for cheating, prohibition is unlikely to be effective. Sue’s resistance-focused mindset also limits Sue’s ability to see potential benefits.

Given Sue’s departmental mandate to adopt AI, participants suggested that Sue needs to adapt course assignments, build an AI policy and model good practices with examples. Rather than focusing on detection, participants noted that Sue could benefit from a perspective shift, reframing her question from “what is the best AI cheating detector?” to “what are the best use cases for AI?” This shift becomes even more important when considering that students face a steep learning curve in understanding and using AI properly. If Sue learns AI herself, this will equip her with the necessary skills to better manage student AI use in learning.

The working definition drafted by the participants for Sue reflects this shift: “having access to good models and examples of incorporating AI into the classroom, and the awareness of the limitations of detection software.”

Participants’ thoughts on the profile Sue, examining the risks, benefits, needs, and a working definition of AI literacy. See the full size image.

After participants returned to the main room and shared their ideas in plenary, the workshop concluded with facilitators’ synthesis of the meeting and encouraged participants to think about the priorities they would like to explore further to support AI literacy on their campuses.

As the project continues, Ithaka S+R will work with participating institutions to develop qualitative instruments for subsequent interviews with students and faculty, helping individual institutions ideate tangible solutions to the challenges and opportunities identified through their interviews.

Ithaka S+R is organizing an additional cohort of this project that will launch in the fall. Several spots are still available. If you’re interested in participating, please contact Dylan Ruediger (dylan.ruediger@ithaka.org).