Copyright and Streaming Audiovisual Content in the US Context

Introduction

The transition to streaming as the predominant format for consuming audiovisual media has led to a number of complications for US higher education. Many universities have built up impressive collections of audiovisual media in older formats, particularly feature-length movies and documentaries in VHS and DVD—content that students, instructors, and researchers would now prefer to consume through a streaming format. Obsolescence of the technology required to play these types of materials makes it challenging for users to access them.

Copyright law includes special rights for research and teaching,[1] including the fair use right, which can help address gaps between the educational activities that technology facilitates and the exclusive rights copyright grants to authors. In this brief, we review how US copyright law currently applies to streaming content for educational and research purposes and explore the opportunities for academic libraries.[2]

During the pandemic, the preference for streaming became a necessity as in-person learning and research was curtailed. Some, but crucially not all, of this content is available by streaming under licenses from vendors, but the landscape for educational licensing is far more limited than for mainstream consumption, and the costs can be prohibitive. The technology exists to digitize pre-existing collections and host them digitally in a streaming format, but resource barriers can severely restrict the extent to which universities can take advantage of this solution. To further complicate this problem, streaming providers may release some content exclusively in a streaming format, and not make it available in a tangible digital format at all.

The Legal Landscape

US copyright law protects specific “types” of works and one of the categories of protected works is “audiovisual works” (17 USC 101), defined as “works that consist of a series of related images which are intrinsically intended to be shown by the use of machines, or devices such as projectors, viewers, or electronic equipment, together with accompanying sounds, if any, regardless of the nature of the material objects.” “Motion pictures” are an example of a subcategory of audiovisual works also defined by this statute.

When an institution streams copyrighted audiovisual content, the exclusive rights of copyright holders may be implicated, such as the right to reproduce, distribute, or publicly perform the copyrighted work. It is important to also recognize the relative infancy of audiovisual content in relation to physical print, which means that relatively little of it will be considered in the public domain under US law. The US Copyright Act includes specific exceptions that allow for classroom performances and displays, as well as digital transmission of works for educational purposes. Exemptions to the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) allow researchers, scholars, and others to circumvent digital locks to access copyrighted materials for some educational and research purposes; these are narrowly crafted to allow access under specific circumstances. When licensing digital content rather than purchasing it, a library must consider what activities are allowable under US Copyright Law, as well as whether the license restricts what copyright law would otherwise allow. The following sections elaborate on these copyright, DMCA, and licensing issues.

The US Copyright Act: Rights and Exceptions

Section 110(1) of the 1976 Copyright Act—drafted before the internet—allows for the performance of an entire audiovisual work without a license from the copyright holder, in a classroom or similar place devoted to instruction “in the course of face-to-face teaching activities of a nonprofit educational institution.” While this exception is strong in that it allows an entire film to be played, it is somewhat limited by the requirement that films be played in a face-to-face classroom or classroom-like setting. However, this exception may have some leeway in the digital environment—for instance, allowing for the streaming of a film from an on-campus server to a physical classroom—though it is still to be determined the extent to which this exception can be applied to online education scenarios where members of a class are joining remotely from different locations. For example, one could argue that synchronous online education could qualify as “face-to-face teaching” occurring in a “similar place devoted to instruction” as required by 17 USC 110(1).

Section 110(2)—the TEACH Act—was enacted in 2002 and was specifically designed for distance education, allowing for the performance of reasonable and limited portions of audiovisual works and dramatic works that are transmitted digitally. The COVID-19 pandemic during which most learning shifted online demonstrated the limited utility of this exception; it is useful if a teacher is planning to show clips, but less so if the curriculum calls for students to view an entire film, which it often does.

The good news is that in addition to using sections 110(1) and 110(2), libraries and educational institutions may rely on fair use to permit the streaming of full-length films. There is a four-factor test for determining fair use that includes consideration of whether a use causes “market harm” (as per 17 USC 107). While fair use must be determined on a case-by-case basis, uses that are noncommercial and educational in nature tend to favor a fair use conclusion. Streaming copyrighted content to individual researchers rather than to multiple students in a classroom would also require a copyright analysis. Here, researchers and faculty may rely on a fair use argument that would be strengthened by the limited market impact; in other words, a researcher accessing streaming digital content to conduct text and data mining analysis is not a substitute for consumer access to the work. The “transformative use” aspect of the fair use analysis would also likely be strengthened, particularly in the case of text and data mining.

Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) Exemptions

Vendors or publishers may apply technological measures to prohibit uploading of audiovisual content to servers for broader distribution. The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) prohibits circumventing technological protection measures to access copyrighted material even for lawful purposes (17 USC 1201). Here, researchers and educators in certain circumstances may rely on exemptions that the librarian of Congress issues every three years.

For instance, current exemptions allow users to circumvent technological protection measures to access “short portions” of motion pictures available on DVD or via digital transmission for the purpose of criticism or comment, including in documentary filmmaking, and for educational purposes, including by college and university faculty or students.[3] However, in the most recent rulemaking, the librarian of Congress rejected a request to expand the exemption to cover full-length motion pictures. A separate exemption allows researchers to circumvent digital locks to access copyright-protected literary works and motion pictures for the purpose of text and data mining. Additionally, the librarian of Congress granted an exemption allowing libraries and archives to circumvent digital locks on DVDs for the purpose of preserving motion pictures.

Licensing Copyrighted Content

Most content is now licensed to libraries in digital formats; in 2020, ARL libraries spent a median of 80 percent of their acquisitions budget to license electronic resources.[4] Licenses often have additional restrictions, including allowing personal use only or permitting no uses other than those authorized by the rightsholder. Even in circumstances where there may be a strong fair use argument, and the desired activity is allowable under a DMCA exemption, licenses may still prohibit streaming activity.

In such situations, a library may consider whether the license is enforceable. Courts are not unanimous in whether there is “manifestation of assent” (mutual agreement to the terms of a contract) sufficient to form a contract in scenarios when rights holders use shrink-wrap licenses, which claim that as a user opens a DVD or uploads content they agree to certain terms.

In addition to questioning whether the license is enforceable, a library may wish to consider whether the terms of the license might be preempted by the Copyright Act. For instance, as discussed above, the Copyright Act explicitly allows for educational streaming under Section 110(1) and 110(2), as well as fair use; would these exceptions take precedence over a license that prohibits or restricts such uses? The legal landscape is unclear, as there is very little case law on this issue. Depending on the fact pattern, one might argue that the prohibition on streaming in the contract can be preempted, but this type of case has not yet been litigated.

While the consequences for breaching a license are less than infringing copyright (which includes the risk of responsibility for actual damages rather than statutory damages), it is not necessarily something to be encouraged. Ultimately, courts must resolve the issues as to whether license terms are preempted by exceptions to the Copyright Act.

On-the-Ground Implications

According to a recent research report by the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA), 83 percent of libraries surveyed experienced “copyright-related challenges” during the pandemic, and the legal questions around playing films in online class settings was among those challenges.[5] The scope of this challenge is reflected in Ithaka S+R’s recent survey of US academic libraries’ streaming media practices, which found that libraries are more likely to make digitized VHS/DVDs available for a specific use case (70 percent), for example to students enrolled in a specific course, as opposed to making the content available broadly (24 percent).[6] The survey also found that libraries are more likely to make a file available for a limited amount of time (46 percent), which may indicate alignment with a particular semester, as opposed to an unrestricted length of time (13 percent).

On March 31, 2022, the Association of Research Libraries and Ithaka S+R co-hosted a convening to explore further how the issue of streaming and digital rights is affecting academic libraries on the ground with library representatives from 12 institutions. We greatly appreciate their willingness to share about their experiences and needs, and the contributors are acknowledged in Appendix 1.

The Challenges

Participants shared that they are licensing and streaming more content than they were before the pandemic; however, licensing options are not always available. Some libraries put digitization practices in place before the pandemic that have since been, or are in the process of being, shut down. Their experiences echo findings from the Ithaka S+R survey: libraries are nearly evenly divided in their practices around digitizing audiovisual content. Forty-six percent of libraries digitize VHS tapes and/or DVDs in their physical collections and 49 percent of libraries do not. Most libraries that digitize audiovisual content do so on a relatively small scale. Of these libraries, more than half digitize only between one and ten titles per year, and 72 percent digitize 50 or fewer titles.

Participants also shared their frustrations with how consumer-facing streaming services that do not offer institutional licensing can create a stumbling block for faculty and students trying to access content that is exclusive to these services.[7] Students may not have a credit card or bank account to set up a personal subscription or the cost may be prohibitive. These consumer products disregard the concept of academic fair use by restricting otherwise lawful uses through their terms of service. And, it can be challenging for libraries to communicate with faculty and students about the availability of content in this changing landscape.

Seeking Help

In addition to exploring the challenges libraries face, the session also examined where those working in libraries can ask questions about streaming resources and digital rights and what other help they need. The participants described how there is no uniform copyright expertise on campuses; where possible, libraries rely on copyright librarians or general counsel.

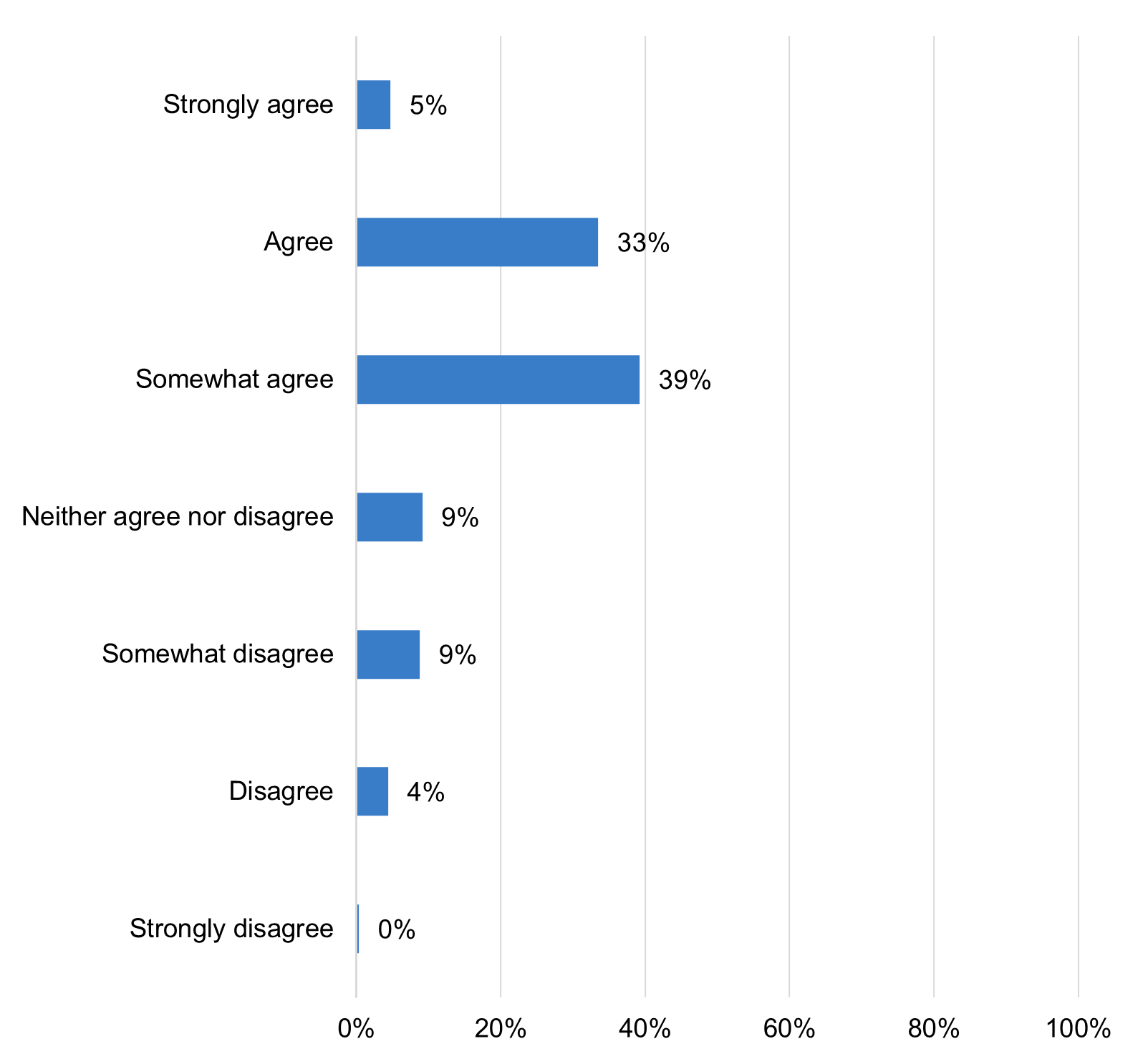

Ithaka S+R’s survey sheds additional light on how these decisions are being made on campus. The survey found that the library collections officer is most commonly the person who decides which audiovisual content gets digitized (44 percent) as well as the person responsible for interpreting copyright regulations and restrictions in the context of the streaming format (43 percent). Library deans and directors (34 percent) and acquisition librarians (26 percent) are also commonly involved in interpreting copyright guidelines in the context of the streaming format. Interpretation of copyright is a crucial and sometimes complicated task. The majority of respondents to this survey (who hold a range of titles) agree to some extent that they are confident in their ability to interpret copyright regulations and restrictions in regard to streaming specifically. However, the majority selected “somewhat agree,” illustrating that additional training or support around interpreting copyright may be warranted.

Please read the following statement and indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree. I am confident in my ability to interpret copyright regulations and restrictions in regard to streaming media specifically.[8]

The participants pointed to a number of resources that they have found helpful for their needs. This includes the University of Pittsburgh copyright committee listserv, the Copyright First Responders Pacific Northwest, the Colorado Alliance of Research Libraries, and online LibGuides. Participants mentioned that access to a central knowledge base including articles and expert opinions on streaming services in academic libraries would be a huge help. Some libraries leverage consortia to access and share video offerings.[9] Others use tools like Berkeley’s VideoLib listserv.[10]

The focus group participants made several recommendations for further action to help clear the way for greater access to streaming resources for their faculty and students:

- Pushing major streaming services to offer educational subscription models that are not prohibitively expensive and perhaps developing model licenses for educational uses.[11]

- Advocating for stronger exemptions for educational uses, possibly in partnership with filmmakers. Working with streaming services in this way may also help identify whether the availability of the necessary license is the decision of the rightsholder or the streaming service.

- Working together with the higher education community to inform lawmakers about the longstanding precedent of lawful resource sharing and academic fair use.

- Pursuing a sector-wide strategy for research libraries that does not shift pressure to public libraries.

- Enlisting consortia to offer guidance to members on how fair use may support academic uses of streaming content or share information about license terms and prices among member institutions to assist with negotiations; consortia may even consider pursuing consortial contracts for audiovisual content in the streaming format.

Moving Forward

There are a number of opportunities for the US academic library community to work together and advocate for more favorable terms for streaming audiovisual content for educational and research purposes. Most notably, the Library Copyright Alliance (LCA) will continue to petition for exemptions for educational uses through the DMCA triennial rulemaking process.[12] LCA serves as the voice of the library community in influencing copyright policy. For instance, LCA successfully petitioned the librarian of Congress to grant an exemption for libraries and archives to preserve motion pictures stored on DVDs in their collections.

As suggested by focus group participants, libraries and higher education may be able to work together in coalition to inform Congress about how copyright has worked during the pandemic. This could take the form of congressional briefings, perhaps with participation from filmmakers. Libraries and higher education associations could also consider collaborating on a legislative hearing centered on the 20th anniversary of the TEACH Act, to review the effectiveness of the law in the distance learning environment.

It is also important to gather additional evidence to demonstrate to lawmakers why the evolving context of teaching and research online necessitates updating how streaming activities are implicated through digital rights. For example, libraries could urge members of Congress to request a Congressional Research Service (CRS) report—a nonpartisan, trusted analysis of legal, legislative, and policy issues—on access to streaming content for educational uses. The library and higher education community can also consider working with the Copyright Office to hold a roundtable discussion or study to generate a record of the effectiveness of the TEACH Act and the limitations and exceptions discussed above, as well as how the DMCA interacts with higher education in a distance learning setting.

There is much work to be done to ensure that students, instructors, and researchers can benefit fully from the affordances of the streaming format for audiovisual content. For instance, faculty teaching classics or literature may use both film and television shows to help students see how old storylines are reused over and over, or to have students closely study these same materials to understand technical concepts like camera movement, lighting, and so forth. These are highly creative works, but arguably these are very defensible fair uses. Given the considerable resources institutions have already invested in audiovisual collections in other formats, and the amount they are increasingly spending on licensing, it is also imperative for institutions to advocate for laws that enable them to responsibly steward their resources. For this reason, streaming represents a crucial test case for determining whether US universities can make full use of the materials needed to be truly competitive in education and research.

Finally, it is important to recognize that while this issue brief has focused on the user perspective in academic contexts, the evolution of the policy landscape to account for the ascendency of the streaming format must also take into consideration the rights of content creators.

To learn more about digital rights, please visit knowyourcopyrights.org, an ARL project to help research libraries proactively assert their rights, and to inform the Association’s public policy and advocacy agenda. And, to stay engaged with the research library community on this and related issues, please follow @ARLPolicy.

Endnotes

-

See the Association of Research Libraries, “Know Your Copyrights,” for a guide to these uses, https://www.arl.org/know-your-copyrights/.↑

- This issue brief is not designed to provide specific legal guidance for an individual or organization. We thank Jonathan Band, Marcie Kaufman, and Nancy Kopans for providing general guidance on the broader legal context relevant to this topic. ↑

- See “Rules and Regulations,” Federal Register 86, no. 206 (28 October 2021), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2021-10-28/pdf/2021-23311.pdf. ↑

- See “ARL Statistics 2020 Data Set,” Association of Research Libraries. ↑

- International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions, How Well Did Copyright Laws Serve Libraries during COVID-19? May 2022, https://repository.ifla.org/bitstream/123456789/1925/1/IFLA-Copyright-COVID-libraries-FINAL.pdf. ↑

- Danielle Cooper, Dylan Ruediger, and Makala Skinner, Streaming Media Licensing and Purchasing Practices at Academic Libraries, Ithaka S+R, 9 June 2022, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.316793. ↑

- This may not be entirely up to the streaming service; rights holders may not make the appropriate license available. ↑

-

This graph originally appeared as Figure 10 in Danielle Cooper, Dylan Ruediger, and Makala Skinner, Streaming Media Licensing and Purchasing Practices at Academic Libraries.↑

- For more information on Copyright First Responders Pacific Northwest see https://sites.google.com/site/cfrpnw/home; for more information on the Colorado Alliance of Research Libraries see https://coalliance.org/streaming-interlibrary-loan-video-resources-sillvr. ↑

- For more information on the VideoLib listserv see https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/FMRTlists. ↑

- In some instances, this is not the decision of the streaming services; the rightsholder may license content in a way that restricts streaming to the consumer market. ↑

- LCA members include ARL, the American Library Association (ALA), and the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL); see https://www.librarycopyrightalliance.org/. ↑