Enrolling More Veterans at High-Graduation-Rate Colleges and Universities

-

Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Available Data on Veterans Postsecondary Educational Access and Attainment

- Barriers Preventing Veterans from Enrolling in High-Graduation-Rate Institutions

- Strategies for Increasing the Enrollment of Veterans at High-Graduation-Rate Colleges and Universities

- The Role of For-profit Institutions

- Conclusion

- Appendix A: Examples of Current Programs Matching Veterans to High-Graduation-Rate Colleges and Universities

- Appendix B: Federal Government Veterans Education Benefits

- Additional Resources

- Advisory Group Participants and Other Selected Veterans Support Organizations and Resources

- Endnotes

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Available Data on Veterans Postsecondary Educational Access and Attainment

- Barriers Preventing Veterans from Enrolling in High-Graduation-Rate Institutions

- Strategies for Increasing the Enrollment of Veterans at High-Graduation-Rate Colleges and Universities

- The Role of For-profit Institutions

- Conclusion

- Appendix A: Examples of Current Programs Matching Veterans to High-Graduation-Rate Colleges and Universities

- Appendix B: Federal Government Veterans Education Benefits

- Additional Resources

- Advisory Group Participants and Other Selected Veterans Support Organizations and Resources

- Endnotes

Acknowledgements

The authors of this report would like to thank:

- Our partners at College Board, especially Bruce Shahbaz, for being valuable collaborators in getting this work off the ground.

- Adam Behrendt and Wick Sloane for insightful contributions to this report. In addition, we would like to thank Michael Abrams, Peter Awn, Marcus Felder, Timothy Groves, LeNaya Hezel, Jason Locke, Walter Ochinko, James Schmeling, Louis Soares, Paul Viau, Ben Wildavsky, and Josh Wyner for assisting with the planning for both this paper and the Improving College Opportunity for Veterans convening in Washington, D.C.

Introduction

Higher education plays a vital role in raising income, moderating income inequality, and increasing economic growth and global competitiveness. But U.S. higher education attainment continues to lag for lower-income and underrepresented-minority students, particularly at the colleges and universities that have the most resources and the highest graduation rates. As a stark example, research by economist Raj Chetty and his team found that there are more students from the top one percent of the income distribution at the Ivy-Plus colleges than from the bottom half of the income distribution.[1] Recognizing this, increasing attention has been paid over the last couple of decades to increasing economic and racial diversity at the nation’s top colleges and universities.

Our nation’s military veterans are another underrepresented group at these well-resourced institutions. Only one in ten veterans using GI Bill benefits enrolls in institutions with graduation rates above 70 percent, while approximately one in three veterans using GI Bill benefits attends a for-profit institution.[2] According to another recent analysis, of the nearly 900,000 veterans enrolled in undergraduate and graduate programs using post 9/11 GI Bill and Yellow Ribbon funds, only 722 undergraduate veterans are enrolled at 36 of the most selective private, non-profit colleges in the United States.[3] There are a variety of explanations for this underrepresentation—including that veterans are often from lower-income or racial/ethnic backgrounds that are traditionally underrepresented at these schools. There is ample reason to believe we can and should do better.

Increasing the enrollment of veterans who are prepared to excel at such colleges and universities—reducing the “under-matching” that leads well-qualified students to enroll in less competitive institutions where they are less likely to graduate—would benefit veterans, the institutions, and our nation. These institutions offer the surest path to a degree and high post-college earnings. Veterans who have served our nation deserve the opportunity to access the pathways to leadership and opportunity that are disproportionately found at well-resourced colleges. Enrolling more veterans would further these institutions’ commitments to diversify the backgrounds and perspectives of their students, which benefits all students. It could also help these colleges look more like America, regaining the public trust that has been severely challenged in recent years.

Many community colleges and regional four-year publics have large enrollments of veterans and in many cases are serving their needs well. But American higher education is highly stratified, and the private non-profit and public flagship colleges and universities with more resources and high graduation rates could do more. If more veterans attended the colleges and universities that best match their academic credentials, have the highest graduation rates, and have the most success in placing students in graduate programs and successful careers, the higher education sector will be doing a major service to our veterans and our country.

In this report, we outline the data on veteran college enrollment and success, discuss some of the barriers—for both institutions and student veterans—to increasing opportunity for veterans at high-graduation-rate colleges and universities, and suggest strategies for overcoming those barriers, including a review of some of the institutions and programs currently seeking to address these issues. The efforts underway give us reason for optimism, but they also exist at a small scale. To enact the changes in recruiting, admissions, reporting, and knowledge-sharing that will improve veterans’ college match at scale, it is clear to us that a broader effort—knitting together multiple institutions and organizations that engage and support service members and veterans throughout the postsecondary pipeline—is needed.

Available Data on Veterans Postsecondary Educational Access and Attainment

The data available on veterans’ education attainment or use of educational benefits has several limitations.[4] Nevertheless, the data that are available tell us a few key things about student veterans:

- The pool of veterans without a bachelor’s degree is large. The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) estimates that by 2021, there will be about 5.1 million veterans who were on active duty after September 10, 2001 (Post-9/11 Veterans).[5] Of those Post-9/11 Veterans, 32 percent have a bachelor’s degree or higher, which means that 68 percent do not. According to Student Veterans of America’s National Veteran’s Education Success Tracker, approximately 37 percent of Post-9/11 Veterans had earned an associate’s degree or certificate and approximately 18 percent were still enrolled in a postsecondary program by the end of 2015.[6] At the same time, the VA reports that only 13 percent of Post-9/11 Veterans were using their educational benefits.

- Veterans are overrepresented in two- and four-year for-profit institutions and underrepresented in public four-year institutions.[7] In 2015-16, veterans accounted for approximately five percent of all undergraduate and graduate enrollment in IPEDS institutions nationally, but represented 13 percent of students enrolled in for-profit institutions.[8] This overrepresentation is driven largely by the four-year for-profit sector. Twenty percent of veterans are enrolled in four-year for-profit institutions, although for-profit enrollment accounts for just six percent of all IPEDS enrollment. Four percent of veterans are enrolled in two-year for-profit institutions compared to two percent of all IPEDS enrollment. By contrast, 53 percent of veterans were enrolled in public four- or two-year IPEDS institutions in 2015-16, compared to 68 percent of all students enrolled in IPEDS institutions.

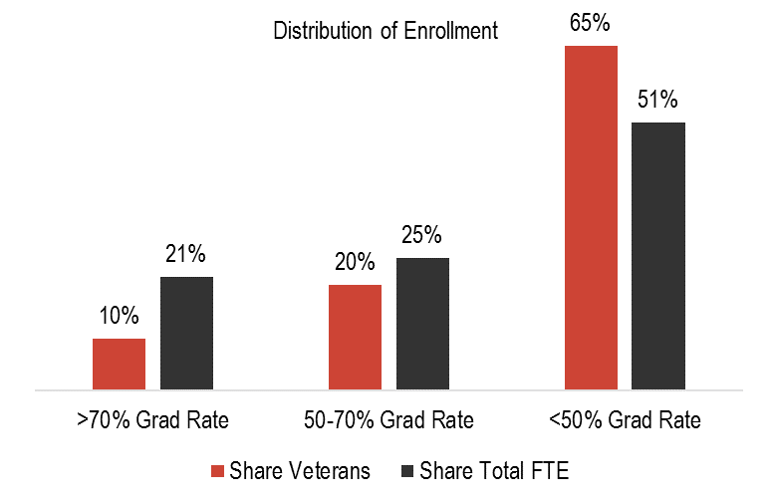

- Veterans are half as likely to enroll in high-graduation-rate institutions – those two- or four-year institutions where at least 70 percent of students graduate in three or six years, respectively. Ten percent of veterans are enrolled in these high-graduation-rate institutions compared to 21 percent of all students. Veterans are much more likely than other students to enroll in institutions where fewer than 50 percent of students graduate in 150 percent of normal time. Sixty-five percent of veterans are enrolled at these low-graduation-rate institutions compared to 51 percent of all students.

- Student veterans have the potential to succeed. As documented in a report from the National Veteran Education Tracker (NVEST) Project, post-9/11 veterans have the potential to succeed at high-graduation-rate institutions.[9] Student veterans are 1.4 times more likely to earn a certificate or degree than adult learners overall, and student veterans have an average GPA of 3.34, compared to the average for traditional students of 2.94.[10] At the same time, with the educational benefits available to them, as detailed in the Appendix, one might question whether the veteran attainment rate shouldn’t be higher still.

Barriers Preventing Veterans from Enrolling in High-Graduation-Rate Institutions

A variety of explanations exist for the underrepresentation of veterans at high graduation rate institutions. Some of these explanations relate to the demand on the part of veterans for attending such institutions. Some relate to the behaviors of the institutions, rather than the veterans. Effectively increasing the representation of veterans at high graduation colleges and universities will require changes on the part of both veterans and these colleges and universities.

Barriers for veterans

When veterans are thinking about pursuing higher education, they do not always consider a wide array of choices. Few apply to the institutions with the highest graduation rates and the most resources. They may perceive that these institutions are not for them, whether because of sticker price, high academic selectivity, or elite campus culture. In some cases, veterans may not even know these schools exist. While some organizations are working hard to introduce veterans to high-graduation-rate colleges (Service to School, the Posse Foundation, and the Warrior Scholars Program in particular), many of those advising veterans on their postsecondary options also may not view these colleges and universities as viable options, and steer them towards other institutions. This is exacerbated by the fact that, traditionally, these institutions have admitted so few veterans that many veterans and those advising them may feel as though the application is not worth the time. This is not dissimilar to the challenges of enrolling more first generation and lower income students. To address this issue, veterans have to be convinced that these institutions are great options for them.

Transfer policies also contribute to the underrepresentation at high-graduation-rate institutions. Many veterans have accumulated some college credits, perhaps while in the military using the Department of Defense tuition assistance program, or after first leaving the military and reintegrating into civilian life, often at a local community college or on-line (not-for-profit or for-profit) program.[11] Many of the high graduation-rate, well-resourced schools take few transfer students or accept limited numbers of transfer credits.

Columbia University is an outlier in this regard. In spring 2018, Columbia enrolled approximately 800 veterans, including nearly 500 undergraduate student veterans. Part of Columbia’s success is explained by its School of General Studies, which allows student veterans to transfer existing credits when they enroll at Columbia. An institutional commitment to enrolling and supporting veterans will be well served by a commitment to enrolling additional transfer students. Some veterans may earn some sort of credit while in the military, making them technically transfer students, while many others may be looking to transfer from two-year institutions to four-year institutions. Recent research indicated that, while across all four-year institutions, 32 percent of new students are transfer students, across the institutions with the top graduation rates, only 18 percent of new students are transfers, and at the subset of private, non-profit institutions, the rate is only nine percent.[12]

Financial aid policies for transfer students may also pose a barrier to enrollment for veteran students. Transfer students or students attending separate schools within the college may not be eligible for the same need-based financial aid as students who entered as freshman. In Columbia’s case, for example, the School of General Studies primarily provides merit-based aid. Veterans attending use their GI Bill benefits, including the Yellow Ribbon program, but are not eligible for institutional need-based financial aid.[13]

Schools may also disadvantage transfer students in the course enrollment process, giving preference to returning students or students housed in the main college of the institution. Depending on the institutional context, it may be advantageous for veterans to enter as freshman and use accumulated credits on a path to graduate early, while in other cases, addressing transfer policies may be required.

Even if they do not enter as transfer students, general financial aid policies can create a roadblock for student veterans. Not only do institutions have widely varying policies, but some of these policies, such as not providing financial aid information well in advance of admissions decisions deadlines, or treating students with dependent status regardless of circumstance, may specifically deter students from attending, even if admitted.

In addition, many veterans have family or work responsibilities. To the extent these institutions require full-time enrollment or on-campus residency, or simply make it more difficult for students to balance work and family responsibilities with their studies, veterans may be dissuaded or unable to enroll.

Finally, the current lack of standardized reporting on veterans enrollment and outcomes presents another challenge for prospective student veterans. There is significant nuance and variety when it comes to how institutions treat veterans academically, socially, and financially. Policies surrounding credit transfer, financial aid, and housing can vary widely, and in many cases, this information is not easily discoverable, or comparable across institutions, for a prospective veteran student. Many institutions do not report any statistics related to veteran enrollment on their websites, and those that do have room to do more. Commonly, data reported publicly do not distinguish between undergraduate and graduate student veterans or veterans and dependents of veterans. However, institutions do have this information, and would serve not only prospective veteran students, but also the broader public, by sharing publicly.

Barriers for colleges and universities

While student veterans are certainly in need of specific supports for post-secondary success, there is broad misunderstanding surrounding what these supports might look like. Some examples of these misconceptions which may be preventing high graduation rate colleges and universities from actively recruiting veterans include:

Myth 1: Veterans will require extensive and expensive mental health support

It is often suggested that enrolling additional veterans will necessitate an increase in the provision of mental health services. While it is certainly true that adjustments might need to be made so institutions are better equipped to address veterans’ needs, the data suggest that the increasing need for mental health services stems more broadly from the total student population.

It is estimated that approximately 30 percent of Post-9/11 veterans have PTSD, while 38 percent have been diagnosed with depressive disorder.[14] At the same time, a spring 2017 report found that 61 percent of college students felt “overwhelming anxiety” and that 40 percent had felt so depressed in the prior year that it was “difficult to function.”[15] A 2015 report from the Center for Collegiate Mental Health estimated a 30 percent increase in student counseling center visits between 2009 and 2015.[16] It can reasonably be concluded that mental health needs are prevalent across college campuses, regardless of veteran enrollment.

It is also the case that some of the better resourced institutions have greater student support services, and it seems reasonable that veterans, as well as traditional students, should have access to these services.

In addition, veterans have access to VA services. In many cases, their mental health needs can be met through VA benefits. However, survey data show that many veterans do not use the VA services available to them, in large part due to lack of awareness.[17] Without incurring additional costs, institutions can provide student veterans with information about their VA benefits.[18]

Myth 2: Veterans are not successful in academic environments

Another common misconception related to student veterans is that they joined the military after high school because they lacked skills to succeed in college. In reality, student veterans have nearly all completed high school or an equivalent (99 percent), compared with a US average of about 75 percent,[19] and three-quarters of student veterans cite advancing their education, by utilizing GI Bill funds, as a strong motivation for entering the military.[20] Once entering college, student veterans tend to have higher average GPAs (3.34) as compared to traditional students (2.94), and graduate at higher rates as well.[21]

Veterans are resilient and committed, and have often received skill training, for example on teamwork and leadership, that directly translates to academic success. With the right support, student veterans can have an extremely successful academic experience, and will enrich the experience of peers.

Myth 3: Veterans may have difficulty assimilating to the campus and classroom

Student veterans are more likely than other students to be older, be married, and have children.[22] Veterans are also more likely than the nonveteran population to be Republican, and this holds true across all age groups (34 percent vs. 26 percent overall).[23] Veterans as a group are incredibly diverse and will not always fit the stereotype. This diversity, and the richness of experience that veterans can bring to the classroom, enhances the educational endeavor for all and could help counter current negative perceptions of higher education, particularly of the more “elite” selective colleges and universities.

In addition to these myths which may be affecting the demand for veterans on the part of some colleges and universities, the high-graduation-rate, well-resourced institutions that currently underserve veterans face a variety of constraints in doing so.

The transfer issue is significant for colleges. Many of these institutions take very few transfers. Many veterans have accumulated credits, and do not want to start over and forfeit these credits. There are possible solutions, from increasing the number of transfers to allowing veterans to enroll as first years but graduate early using these credits when appropriate.

Improved recruitment of an often-overlooked population is also vital for high-graduation-rate colleges. Many for-profit institutions have succeeded in recruiting veterans (although they have not succeeded at graduating them at high rates). High-graduation-rate institutions should study the for-profits’ approach to reaching veterans and learn from it. In addition, the student experience matters. A veteran’s chance of success will increase with a critical mass of other student veterans on campus, and at many of the high-graduation-rate institutions, this is not a reality. The Posse Veterans Program addresses this issue in the same way that the program has for lower income and underrepresented minority students. Other colleges and universities can accomplish similar ends by recruiting larger numbers of veterans, and by working to create a veterans community on campus.

Working successfully with older undergraduates may be a challenge for colleges and universities that haven’t traditionally enrolled many students in this demographic. Veterans are more likely to have families and may have different needs in terms of campus life than traditional-age undergraduates. Universities with graduate programs will have more experience with older students and may be better able to accommodate a variety of needs, such as married student housing, less likely to be available at predominantly undergraduate institutions.

More generally, and related to the myths discussed earlier, some institutions may also have concerns that veterans require different or additional forms of support than those currently offered.

Strategies for Increasing the Enrollment of Veterans at High-Graduation-Rate Colleges and Universities

Recruiting

Colleges and universities need to develop recruitment strategies explicitly aimed at veterans. Schools need new approaches, given that veterans will not generally have been exposed to the high school marketing from these colleges. They also need to help veterans understand that these schools are not only realistic options for them, but great options. Strengthening the advising available for veterans from enlisting through to college, including time in community college is one way to do this. Becoming engaged with national programs that focus on helping veterans attend and succeed at strong four-year colleges and universities, such as the Posse Veterans program, the S2S (Service2School) program, and the Warrior-Scholar Project program can also help, though greater scale is needed than these programs currently provide. These programs and several others are described in greater detail in Appendix A.

Admissions Criteria

Schools can also reconsider how they evaluate applicants. Many veterans have received significant further training post-high school while in the service, and also have discovered a greater personal commitment to and motivation for further education. Admissions officers need to evaluate applicants by looking beyond their high school credentials at their experiences and training in the military, which can provide significant insight and evidence on veterans’ abilities and motivation.

Recognizing the academic value of military training through programs such as ACE’s credit service holds some promise in this regard. Providing opportunities to active duty military personnel and veterans to demonstrate their academic qualifications directly, such as by streamlining administration of the SAT and the CLEP exam, and other national exams, such as the ACT, and facilitating matching with institutions would also be valuable. Finally, there are tests administered by the military that may be useful in matching students to institutions based on their skills, such as the ASVAB (Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery), which measures strengths and weaknesses in areas such as arithmetic reasoning, math knowledge, and verbal composite.[24]

Some centralized clearing house of veteran credentials may be a useful tool, for both veterans pursuing higher education and institutions seeking to increase their enrollment of veterans. VETLINK, run by S2S, has been working on this issue, and currently has more than fifteen high-graduation rate institutions as partners. VETLINK will assist these institutions in identifying competitive applicants.[25]

Collaboration

Increasingly, colleges and universities are joining together in collaborative commitment and practice-sharing efforts to tackle common problems. These collaborative initiatives provide several advantages. By making public commitments with other institutions, the participants reduce their risk of getting ahead of the field, while also creating public and mutual accountability for follow-through. Engaging with other institutions pursuing similar ends can also yield productive information exchange, as well as new strategies that can be tested across multiple settings.

Many high-graduation-rate colleges and universities are deeply committed to diversifying their student bodies by both race and income. For example, the American Talent Initiative, a group of colleges and universities with high graduation rates committed to enroll more low- and moderate-income students, recently announced a sub-community focused on enrolling and graduating more military veterans. Veterans attending these schools today have also added another source of rich diversity in terms of life experiences to their communities. In addition, one of the challenges for these institutions in diversifying by socioeconomic status is the need for greater resources for need-based financial aid. Veterans relax this constraint, since they come with significant federal benefits.

Collaboration with military services will also play a large role in advising and preparing active military personnel for life after the military, including education. Working with the military on setting up processes that encourage veterans to consider and prepare for a variety of educational opportunities after leaving the military will significantly support efforts of the higher graduation rate colleges and universities to enroll more veterans.

Resources

A variety of centralized resources could make the matriculation of veterans easier at each college and university. Examples include:

- A benefits manual: A manual which simplifies to the extent possible, the GI Bill benefits and the Yellow Ribbon program would be useful to all institutions matriculating veterans. The challenging issues we have identified include 1) how the basic allowance for housing (BAH) is treated in the financial aid calculation 2) how disability benefits are treated 3) whether veterans are treated as dependent or independent students 4) how the GI Bill benefits interact with institutional commitments to need-based institutional aid.

- A campus best practices manual: This would report on best practices campuses can develop to support veterans. Topics could include such issues as advising, the role of a veterans lounge, orientation programs, etc.

- Information on how VA programs can support veteran students.

Reporting

Better information on the number of veterans at institutions and the price that they pay to attend would be helpful. While many colleges report on the number of GI Bill users, this does not measure the number of undergraduate veterans at institutions, but rather everyone, including graduate students and dependents, who access this benefit. In addition, between the GI Bill and Yellow Ribbon benefits and access (or not) to need based financial aid, it is very difficult for veteran applicants to know the cost to attend.

It will be very difficult to make progress without better data. “When performance is measured, it improves. (It improves by the mere fact that it is being measured.) Second, when performance is measured and compared (to goals, history, like units), performance improves still more. And when performance is measured, compared, and significant improvement is recognized and rewarded, then productivity really takes off.”[26]

The Role of For-profit Institutions

For-profit institutions have been successful at recruiting veterans to their programs. There are financial incentives for them to do so. Unfortunately, for-profit institutions have low graduation rates overall, with six-year graduation rates of 26 percent, and the benefits of higher education come in large part from graduating. Furthermore, some for-profit institutions have a history of luring students with unrealistic promises about the labor market value of participating in their programs.[27]

Overall for-profit enrollment has noticeably shifted since 2014-15, with a fairly sharp decline, while veterans enrollment in for-profit institutions has only slightly declined.

There are several issues around the for-profit institutions that need further study. First, how have they been so successful at recruiting veterans? Is there a lesson for other higher education institutions as they move to recruit greater numbers of veterans? Second, is there a way to use credits earned at for-profit institutions to assist in the matching of veterans to other four-year institutions for which they are qualified, and is there a way to use these credits to facilitate graduation?

Several veterans groups are concerned about whether the for-profits are serving veterans well.[28] Moves on the part of Congress and the Department of Education to reduce regulations of the for-profit providers have been opposed by various veteran groups.[29]

Conclusion

While there has been significant research on veterans’ participation in higher education, there is still additional information needed to make further progress, including:

- What is the current representation and success of undergraduate veterans at high graduation-rate campuses?

- What are the most important barriers to expanding opportunity and success for veterans at these colleges and universities?

- Can current efforts to help veterans at these colleges and universities effectively be scaled?

- What other strategies would overcome current barriers and improve on current efforts?

- Is there more we can do to demonstrate the value proposition of high graduation-rate colleges and universities for veterans?

Relatively few veterans are enrolled at the highest graduation-rate and wealthiest colleges and universities today, for a variety of reasons. But, veterans, will have the greatest chance of succeeding and earning a degree if they go to the most selective school possible given their potential. It seems incumbent on us as a nation to make sure that veterans have access to the educational opportunities for which they are ready when they are ready.

Current programs to improve the representation of veterans at the nation’s high graduation colleges and universities show great promise and have highlighted the issues and the challenges. With greater collaboration and cooperation, we can make further progress in scaling the successes to date and overcoming remaining constraints.

Appendix A: Examples of Current Programs Matching Veterans to High-Graduation-Rate Colleges and Universities

In response to the recognition that veterans do not enroll in large numbers in the institutions with the highest rates of student success, a number of organizations have focused on addressing the issue. Some examples include:

Posse Veterans Program[30]

The Posse Program has had a long-standing program of recruiting groups of lower income and underrepresented minority students (“posses”) to attend the high-graduation rate colleges and universities in the country. The Posse Veterans Program, founded six years ago, identifies a pool of qualified veterans and coordinates admission with participating institutions, who select candidates from among the pool. The program also provides advising and mentoring support to Posse students while they are enrolled. Through this program, 10 students (a posse) who are veterans are annually enrolled as first-year students at Vassar College, Wesleyan University, the University of Chicago, and the University of Virginia. The program is working to expand to additional institutions. The institutions participating in the program guarantee free tuition and fees for all four years. Students are eligible for the institutions’ need-based aid, so that more than tuition and fees are covered with financial aid if there is the need. Veterans in exchange are required to use their GI Bill benefits, including their housing allowance, and apply for Pell grants if eligible.[31]

Service to School (S2S)[32]

Service to School (S2S) provides free application advice and assistance to veterans, helping them gain admission to the most selective, best resourced colleges and universities given their qualifications and plans. It also assists veterans in understanding their education benefits and maximizing their use. It is a non-profit that relies on a large number of volunteers.

Veterans who have been helped by S2S become “Ambassadors” and advise new veteran applicants. S2S has helped applicants get admitted to a variety of well resourced, high graduation colleges and universities.

Current schools working with S2S include Amherst College, Bowdoin College, Carleton College, Cornell University, The University of Chicago, Dartmouth College, Emory University, Harvard University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, University of Michigan, University of Notre Dame, Pomona College, Princeton University, Smith College, Swarthmore College, Stanford University, Syracuse University, Williams College, and Yale University.

Warrior-Scholar Project[33]

Warrior-Scholar Project (WSP) is a transition program to help veterans aspire to and succeed at the most selective, well-resourced universities and colleges for which they are qualified. The program is aimed at encouraging veterans to aim high and have the academic confidence to succeed. The program is an immersive one or two-week college preparatory “boot camp” hosted at well resources colleges and universities. These are the type and some of the actual institutions to which WSP is aspiring to place veterans.

The boot camps are free. College and university faculty teach the classes. The curriculum focusses on analytic reading, writing and other skills necessary to academic success in a rigorous program. There are currently two models for the boot camps, a one-week liberal arts version and a two-week version which incorporates a STEM curriculum as well. While at the boot camp, veterans also receive counselling on the college application and admission process.

Other initiatives, including college and university programs

Several high-graduation colleges and universities have been successful at recruiting veterans through a variety of initiatives/programs. Examining these programs to understand how they work and whether they could be adopted and scaled to other institutions will be useful. An inventory of pipeline programs for veterans would be a useful tool for both veterans and colleges and universities.

For example, over the last fifteen years, Columbia University has enrolled more than all of the other Ivy League schools combined.[34] Many are enrolled in the School of General Studies, which specifically caters to nontraditional students. Columbia’s veterans have been largely successful, with a graduation rate above 90 percent. In 2017, Columbia opened its Center for Veterans Transition and Integration, dedicated to supporting veterans transitioning to college and the workforce.

A variety of initiatives are underway. Collaboration among these initiatives has great potential for improving the collective impact.[35]

Appendix B: Federal Government Veterans Education Benefits

The VA reports beneficiaries who received education benefits by type of program through 2015, as well as beneficiaries who began receiving education benefits by training type and program during fiscal year 2015.[36] For example, in 2015, the VA reports that 790,507 veterans were using Post 9/11 education benefits, while 87,272 started using the benefits for undergraduate study that year and another 54,009 were using the benefit for college, non-degree work. These data give an indication of the size of the pool of veterans who are seeking higher education opportunities using their VA benefits. The Post 9/11 GI bill program is the most significant in terms of total beneficiaries (790,507 out of 1,016,664 for six programs listed below, not including Vocational Rehabilitation) and in terms of dollars ($11.2 billion of $12.3 billion total.)[37]

The following programs are reported by the VA:

Post 9/11 GI bill benefits

The Post 9/11 GI Bill offers education benefits for veterans who served on active duty after September 10, 2001. Veterans receive tuition and fee support (paid to the institutions) and a housing allowance (paid to the veteran). They receive a percentage of the maximum benefit depending on the length of service, which varies between 40 percent for at least 90 days to 100 percent for at least 36 months. The maximum Post 9/11 GI Bill benefit covers all in-state tuition and fees at public institutions, on a state-by-state basis. The housing allowance paid to the veteran is called the BAH (Basic Allowance for Housing) and depends on zip code, as well as type of program.

The Yellow Ribbon program provides additional tuition support for veterans attending private degree-granting institutions and veterans paying out-of-state tuition at public institutions. The VA matches any resources contributed by the institution, up to the total cost of tuition and fees that exceed the public maximum benefit. Institutions have to sign up for the Yellow Ribbon Program and enter into an official agreement with the VA. They state the dollar amount that they will contribute to be matched, and also state the maximum number of students for whom they will make these contributions.[38]

Veterans are eligible for 36 months of support. Eligibility for the benefits, which was originally for 15 years from the last period of active duty, has been extended indefinitely.

Vocational Rehabilitation Benefits

Some veterans with service-associated disabilities are eligible for Vocational Rehabilitation Benefits. While not specifically an educational benefit, the VRB can in some instances cover educational costs, and may be a better option for doing so for particular veterans.

Montgomery GI Bill (Active Duty or MCIB-AD)

The Montgomery GI Bill is for service members who first entered active duty after June 30,1985. Service members contribute monthly while serving, unless they opt out at the time of enlistment. In exchange, they receive benefits as veterans.

In 2007/8 the Montgomery GI Bill provided veterans up to $1,101 per month for living and education expenses with an annual maximum of $9,909.[39] The Post 9/11 GI Bill significantly increased educational benefits.

Other

The Montgomery GI Bill (Selected Reserve or MCIP-SR) is for members of the Selected Reserve, including National Guard members. The Survivors and Dependents Educational Assistance (DEA) is designed for spouses and children of certain veterans and service members.[40]

Challenges: Funding Veterans using Yellow Ribbon

As detailed above, private institutions can participate in the Yellow Ribbon program to close some or all of the gaps between GI bill funding and the cost of attendance for veterans. The program presents some challenges for institutions and for veterans, such as:

- Lack of understanding: The Yellow Ribbon program was not established until 2008 (with the Post 9/11 GI Bill), making it a fairly new piece of the financial aid puzzle at many institutions. In addition, the program varies by institution, creating complexity for veterans and making it difficult for financial aid officers to navigate challenges with colleagues at other institutions.

- The role of benefits in the financial aid calculation: Federal student aid guidelines clearly stipulate that veterans benefits are not to be counted as income, and are not reported as such on the FAFSA.[41] However, this is not always the case when calculating institutional aid. This is perhaps most evident when considering the role of the Basic Allowance for Housing (BAH). Unlike GI bill funds, which are dispersed directly to the institution, the BAH goes to the veteran. At some institutions, veterans keep their BAH funds, regardless of circumstance. But others may require that the BAH is signed over to the institution, especially in cases where a veteran may be living in on-campus housing. Given that the BAH is only paid when students are enrolled (oftentimes not 12 months of the year), but that housing needs are year-round, this is an important issue for veterans.

- Partial participation: Many institutions participate “partially” in the Yellow Ribbon program, meaning either that they don’t provide the full amount of funds needed to cover costs, or they limit the number of veterans who can receive Yellow Ribbon funds. In other instances, institutions might provide a “tiered” benefit system for veterans; for example, providing less Yellow Ribbon funding for dependents receiving GI bill benefits.

- Commitment to need-based aid: Many private institutions have policies to only offer need based aid. In these instances, the Yellow Ribbon program may seem like a problem because it could direct funds to veterans who have income or assets, or even to dependents who have little or no need. However, institutions such as Princeton have indicated that a commitment to need-based aid can be made in conjunction with a commitment to full participation in the Yellow Ribbon program.[42] For clarity, it is also important for institutions to make clear that “meeting full need” is not the same as meeting full cost to a student.

The complexity of veteran benefits at private not-for-profit institutions might deter veterans from attending. Institutions working together to provide clarity and to challenge each other to expand benefits is a step in the right direction.

Examples: What does Veterans funding look like?

GI Bill benefits will look different, depending on the student and the school attended. Below are some examples of different funding scenarios for the Post 9-11 GI Bill:

| Student | Length of service | School attended | Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Student #1 | 5 years (60 months) | Public state institution | Length of service makes this student eligible for 100% of their allowed benefits. This equals full tuition and fees paid to institution and housing allowance paid to student for a total of 36 months. |

| Student #2 | 2 years (21 months) | Public state institution | Length of service makes this student eligible for 80% of their allowed benefits.[43] Tuition and fees, as well as the housing allowance, will be prorated accordingly for 36 months. |

| Student #3 | 4 years (48 months) | Private yellow-ribbon institution | At private institutions, benefits equate to the lower of the actual tuition & fees or the national maximum per academic year (~$23,671 for 2018-19 academic year).[44] In addition, this student will receive funds committed by the institution as part of the Yellow Ribbon program. The amount of these funds will vary[45], and the money will only be available if the institution has not yet offered Yellow Ribbon funds to its maximum number of individuals. The student will also receive the housing benefit, which may or may not be then paid to the institution. |

| Student #4 | 1 year (12 months) | Private yellow-ribbon institution | Veterans who do not receive the maximum benefit under the Post-9/11 GI bill due to serving fewer than 36 months are not eligible for yellow-ribbon funds. Therefore, this student will receive the lower of the actual tuition & fees or the national maximum per academic year (~$23,671 for 2018-19 academic year), along with a housing allowance, both of which will be prorated at 60%. |

| Student #5 | 3 years (36 months) | Private institution that does not participate in yellow-ribbon | This student will receive the lower of the actual tuition & fees or the national maximum per academic year (~$23,671 for 2018-19 academic year), along with a housing allowance, for 36 months. The institution may provide additional funds through the standard financial aid process, but will not provide veterans-specific funding as part of the Yellow Ribbon program. |

Other nuances exist- for example, an annual books and supplies stipend is available, paid proportionally based on enrollment, and a rural benefit is also paid to individuals relocating from a rural area to their institution. Also, the examples above assume full-time student status, which does not apply to all veterans. For students attending part-time, benefits would be prorated accordingly. This would mean that benefits may extend beyond the 36 month period.

Additional Resources

Abrams, Michael and Julia Taylor Kennedy. Mission Critical: Unlocking the Value of Veterans in the Workforce. New York: Center for Talent Innovation, 2015.

Bricker, Suzane. An Instructor’s Guide to Teaching Military Students: Simple Steps to Integrate the Military Learner into Your Classroom. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017. https://www.amazon.com/Instructors-Guide-Teaching-Military-Students-ebook/dp/B076VXL2HH/.

Bruni, Frank. “Where are Veterans at Our Elite Colleges?” The New York Times, September 7, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/07/opinion/elites-neglect-veterans.html

Executive Order 13607, “Establishing Principles of Excellence for Educational Institutions Serving Service Members, Veterans, Spouses, and Other Family Members,” April 27, 2012, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2012/04/27/executive-order-establishing-principles-excellence-educational-instituti. This order was passed to protect veterans for predatory practices on the part of higher education institutions.

Kay, Phil. “The Warrior at the Mall.” The New York Times, April 4, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/14/opinion/sunday/the-warrior-at-the-mall.html.

Kotlikoff, Michael I. “Recruiting Student Veterans at Cornell: True to Our Founding Principles” Higher Education Today (ACE), 2017. Available at: https://www.higheredtoday.org/2017/07/05/recruiting-student-veterans-cornell-true-founding-principles/.

Mikelson, John D. and Kevin P. Saunders. “Enrollment, Transfers, and Degree Completion for Veterans.” In Called to Serve: A Handbook on Student Veterans and Higher Education edited by Florence A. Hamrick & Corey B. Rumann, pp. 140-164. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2013.

Molina, Dani and Tanya Ang. “Serving Those Who Served: Promising Institutional Practices and America’s Military Veterans.” In What’s Next for Student Veterans: Moving from Transition to Academic Success, edited by David DiRamio, pp. 79-91. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2017.

NASPA Military Resources, https://www.naspa.org/constituent-groups/kcs/veterans/resources.

Owen, Wilfred. “Dulce et Decorum Est.” Poems (Viking Press: 1921). https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/46560/dulce-et-decorum-est

Pratt Shepherd, Aaron. “For Veterans, a Path to Healing ‘Moral Injury.’” The New York Times, December 9, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/09/opinion/for-veterans-a-path-to-healing-moral-injury.html.

Shay, Jonathan. “Odysseus in America: Combat Trauma and the Trials of Homecoming.” The New York Times, January 13, 2008. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/13/us/excerpt-odysseus.html.

Vacchi, David. “Considering a Unique Framework for Understanding Student Veterans: Research and Implications.” 2012. http://docplayer.net/7789369-Considering-a-unique-framework-for-understanding-student-veterans-research-and-implications.html.

Vacchi, David. “Four Misconceptions Veterans Face in Higher Education.” The Evolllution: A Destiny Solution Illumination, March 3, 2013, https://evolllution.com/opinions/misconceptions-veterans-face-higher-education/.

Vacchi, David and Kristopher Perry, “Standardizing Veteran-Friendliness: Finding a Definition.” The Evolllution: A Destiny Solution Illumination, January 6, 2015. https://evolllution.com/opinions/audio-standardizing-veteran-friendliness-finding-definition/.

Yellow Ribbon Commitments, available at: www.benefits.va.gov/gibill/yellow_ribbon/2017/states

Zoli, Corri, Daniel Fay, Sidney Ellington, and David Sega. “Commentary: Supporting Post-9/11 Military Veterans in Higher Education.” Military Times: Reboot Camp, July 27, 2017. https://rebootcamp.militarytimes.com/opinion/commentary/2017/07/27/commentary-supporting-post-911-military-veterans-in-higher-education/.

Advisory Group Participants and Other Selected Veterans Support Organizations and Resources

- American Council on Education: Military and Veteran Resources

- Aspen Institute College Excellence Program

- Coalition for Access, Affordability, and Success

- College Board Resources for Veterans

- Columbia University: Center for Veteran Transition and Integration

- Defense Activity for Non-Traditional Education Support (DANTES)

- Fidelis

- Georgetown University Veterans Services

- Ithaka S+R

- The Posse Foundation Veterans Program

- Service2School

- Student Veterans of America

- Tennessee Reconnect: Veterans

- University of Central Florida: Veterans Academic Resource Center

- Veterans Education Success

- The Warrior-Scholar Project

Endnotes

- Raj Chetty, John N. Friedman, Emmanuel Saez, Nicholas Turner, and Danny Yagan, “Mobility Report Cards: The Role of Colleges in Intergenerational Mobility,” Working Paper, 2017. ↑

- Data from US Department of Veterans Affairs and IPEDS. There are currently approximately 300 four-year public and four-year private not-for-profit institutions with six-year graduation rates above 70 percent. ↑

- The thirty-six institutions referenced here do not encompass the full picture of well-resourced institutions but are included here because the data is specific to undergraduate students, which is not available from all high-graduation rate institutions. See Wick Sloan, “Veterans at Selective Colleges, 2017,” Inside Higher Ed, November 10, 2017, https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2017/11/10/wick-sloanes-slightly-depressing-annual-survey-veterans-elite-colleges-opinion. ↑

- For example, the nationally available data do not distinguish between graduate students and undergraduates or between veterans and their dependents. (Dependents are eligible to use veteran education benefits in some cases.) If we are focused on improving the educational attainment of veterans, we are mostly interested in veterans, not dependents, pursuing bachelor’s degrees, not graduate degrees. Individual institutions do have these data and could report them. ↑

- United States Department of Veterans Affairs, “Profile of Post-9/11 Veterans: 2016,” National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics, 2016, https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Post_911_Veterans_Profile_2016.pdf. Post-9/11 veterans is a category of interest because the federal government offers special educational benefits for that group and because those individuals are in an age range during which the pursuit of postsecondary education is most common. See the appendix for more information on federal postsecondary educational benefits for veterans. ↑

- Chris Andrew Cate, Jared S. Lyon, James Schmeling, and Barret Y. Bogue, National Veteran Education Success Tracker: A Report on the Academic Success of Student Veterans Using the Post-9/11 GI Bill (Washington, DC: Student Veterans of America: 2017) https://nvest.studentveterans.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/NVEST-Report_FINAL.pdf. ↑

- Unfortunately, the VA data do not disaggregate veteran enrollments by undergraduate/graduate programs, which adds some uncertainty to this analysis. ↑

- This is comparing all undergraduate and graduate enrollment to enrollment at for-profit institutions, and may be underestimating the enrollment at four-year for-profit institutions, since fewer of them have graduate programs. ↑

- Student Veterans of America (SVA) recognized some of the information gaps around the effectiveness of the GI Bill education benefits and has partnered with the Department of Veterans Affairs and the National Student Clearinghouse to provide greater insight. The National Veteran Education Success Tracker (NVEST) Project was developed to measure educational attainment and degree completion of veterans using the Post-9/11 GI Bill. It has done so for veterans using the Post 9/11 GI Bill between 2009 and 2013. See Chris Andrew Cate, Jared S. Lyon, James Schmeling, and Barret Y. Bogue, National Veteran Education Success Tracker: A Report on the Academic Success of Student Veterans Using the Post-9/11 GI Bill (Washington, DC: Student Veterans of America: 2017), https://nvest.studentveterans.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/NVEST-Report_FINAL.pdf. ↑

- Institute for Veterans and Military Families and Student Veterans of America, “Student Veterans: A Valuable Asset to Higher Education,” June 2017, https://ivmf.syracuse.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Student-Veterans_A-VAluable-Asset-to-Higher-Education.pdf. ↑

- Tuition assistance benefits are available, with eligibility criteria differing by service branch. See https://www.military.com/education/money-for-school/tuition-assistance-ta-program-overview.html. ↑

- See author analysis of IPEDS data, Tania LaViolet, Benjamin Fresquez, B., McKenzie Maxson, and Joshua Wyner, “The Talent Blind Spot: The Case for Increasing Community College Transfer to High Graduation Rate Institutions,” American Talent Initiative, 27 June 2018, https://americantalentinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Aspen-ATI_Vol.1_The-Case_07112018.pdf. ↑

- The Yellow Ribbon program includes an institutional commitment to additional financial aid for veterans receiving Post 9/11 benefits, matched by Federal grant aid. The amount depends on the arrangement between each individual institution and the Federal government. ↑

- Institute for Veterans and Military Families & Student Veterans of America, “I Am a Post-9/11 Student Veteran,” June 2017, https://ivmf.syracuse.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/I-AM-A-POST-911-Student-Veteran-REPORT.pdf. ↑

- American College Health Association, American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment II: Reference Group Executive Summary Spring 2017 (Hanover, MD: American College Health Association, 2017, https://www.acha.org/documents/ncha/NCHA-II_SPRING_2017_REFERENCE_GROUP_EXECUTIVE_SUMMARY.pdf. ↑

- Center for Collegiate Mental Health, 2015 Annual Report, January 2016, https://sites.psu.edu/ccmh/files/2017/10/2015_CCMH_Report_1-18-2015-yq3vik.pdf. ↑

- The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, “VA Provides Mental Health Care to Veterans of Recent Iraq and Afghanistan Wars of Comparable or Superior Quality to Other Providers, Yet Substantial Unmet Need Remains,” January 31, 2018, http://www8.nationalacademies.org/onpinews/newsitem.aspx?RecordID=24915&_ga=2.219077337.1376918879.1517434674-983900220.1516218809. ↑

- In some cases, veterans can access VA mental health resources remotely, not even requiring them to travel off campus, which can interrupt their academic program. ↑

- University of Northern Iowa, “Module 8: Myths, Truths, and Commonalities,” 2018, https://military.uni.edu/module-8-myths-truths-commonalities. ↑

- Institute for Veterans and Military Families & Student Veterans of America, “I Am a Post-9/11 Student Veteran,” June 2017, https://ivmf.syracuse.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/I-AM-A-POST-911-Student-Veteran-REPORT.pdf. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Institute for Veterans and Military Families and Student Veterans of America, “Student Veterans: A Valuable Asset to Higher Education,” June 2017, https://ivmf.syracuse.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Student-Veterans_A-VAluable-Asset-to-Higher-Education.pdf. ↑

- Frank Newport, “Military Veterans of All Ages Tend to Be More Republican,” Gallup, May 25, 2009, https://news.gallup.com/poll/118684/military-veterans-ages-tend-republican.aspx. ↑

- Military.com, “ASVAB Test Explained,” 2018, https://www.military.com/join-armed-forces/asvab/asvab-test-explained.html. ↑

- Service to School, “Service to School Partners with Top Colleges to Launch VetLink,” 2017, https://service2school.org/service-to-school-partners-with-top-colleges-to-launch-vetlink/. ↑

- W.L. Creech, “Organizational and Leadership Principles for Senior Leaders,” http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/au-24/creech.pdf. ↑

- Some examples: Larry Abramson, “Promise Of Jobs Lures Many To For-Profit Schools,” NPR, November 23, 2010, https://www.npr.org/2010/11/23/131548529/for-profit-schools-lure-students-with-promise-of-jobs; Susan Clampet-Lundquist and Stefanie Deluca, “Are For-Profit Colleges Failing to Live Up to Their Promises?” Newsweek, May 10, 2017, https://www.newsweek.com/are-profit-colleges-failing-live-their-promises-596583; Peter S. Goodman, “In Hard Times, Lured Into Trade School and Debt,” The New York Times, March 13, 2010, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/14/business/14schools.html. ↑

- Walter Ochinko, “Department of Education Data Shows Increased Targeting of Veterans and Service members, Highlighting Urgency of Closing 90/10 Loophole,” Veterans Education Success, November 2017, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/556718b2e4b02e470eb1b186/t/5a043bdfc83025336298845f/1510226911840/VES+90%3A10+Report+-+FINAL.pdf; Karina Hernandez, “Military Veterans Decry Debt, Useless Diplomas from For-Profit Colleges,” The Hechinger Report, June 7, 2018, https://hechingerreport.org/military-veterans-decry-debt-useless-diplomas-from-for-profit-colleges/. ↑

- Jim Absher, “Veterans Groups Oppose Legislation Loosening Restrictions on For-Profit Schools,” Military.com, March 27, 2018, https://www.military.com/militaryadvantage/2018/03/27/bill-loosens-rules-profit-schools-vet-groups-dont-it.html. ↑

- See https://www.possefoundation.org/shaping-the-future/posse-veterans-program. ↑

- Housing costs are included in the calculation of needed financial aid, justifying the inclusion of the BAH in resources available to cover these costs. ↑

- See https://service2school.org/. ↑

- See https://www.warrior-scholar.org/. ↑

- See https://veterans.columbia.edu/. ↑

- For example, The Veterans in Higher Education Collaborative is aiming to bring together institutions committed to improving educational outcomes for veterans pursuing higher education. To date, the collaborative has convened twice. ↑

- See United States Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Benefits Administration, Education, pp. 1-16. ↑

- Ibid, p. 10. ↑

- These commitments on an institution by institution and program by program basis for each state can be found at www.benefits.va.gov/gibill/yellow_ribbon/2017/states. ↑

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2007, and Stats in Brief, U.S. Department of Education, NCES 2016-435. ↑

- Additional educational benefits programs for veterans have largely wound down. The Reserve Educational Assistance Program (REAP) ended on November 25, 2015. The Post-Vietnam Era Veterans Educational Assistance Program (VEAP) is for service members who first entered active duty after December 31, 1976, and before July 1, 1985, and serves few veterans at this point. ↑

- “Chapter 7: Packaging Aid,” Federal Student Aid Handbook, 2017, https://ifap.ed.gov/fsahandbook/attachments/1718FSAHbkVol3Chapter7.pdf. ↑

- “U.S. Military Applicants,” Princeton University, 2018, https://admission.princeton.edu/how-apply/us-military-applicants. ↑

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, “Post-9/11 GI Bill Eligibility for Active Duty Veterans,” last updated November 6, 2018, https://gibill.custhelp.va.gov/app/answers/detail/a_id/947. ↑

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, “Education and Training,” 2018, https://www.benefits.va.gov/GIBILL/resources/benefits_resources/rates/ch33/ch33rates080118.asp. ↑

- For example, funds will even vary within an institution: see U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, “Academic Year 2018-2019 Yellow Ribbon Program Participation by School,” https://www.benefits.va.gov/GIBILL/yellow_ribbon/yrp_list_2018.asp. ↑

Attribution/NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of the license, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.