Holistic Credit Mobility

Centering Learning in Credential Completion

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the generous support of Ascendium Education Group. We also thank Alison Kadlec and Lara Couturier of Sova and Lexi Anderson of Education Commission of the States for feedback on this work. Any errors or omissions remain the fault of the authors.

Introduction

Today’s postsecondary students accumulate college credit and other validated learning experiences from more sources and in more forms than ever before. Adult learners may complete military or corporate training, obtain credit for prior learning through a competency-based examination, or accumulate credits at multiple institutions along their educational journey. Additionally, high school students routinely earn college credit through dual enrollment programs or exam scores on AP or IB exams. The formal recognition of the many forms and locations in which postsecondary learning takes place honors those students’ experiences and brings them closer to completing their desired postsecondary credential.

As credit accumulation options have proliferated, student mobility patterns have also shifted and are now increasingly multi-directional, crossing institutional types, system and state boundaries, and occurring over longer periods of time.[1] In fact, 45 percent of Associate degree holders and 67 percent of Bachelor degree holders have transcripts from multiple institutions.[2] The intersection of these trends has exposed systemic problems and the challenges that students face when they attempt to not only earn credits but to move those credits between postsecondary institutions. These systemic challenges disproportionately impact students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and contribute to lower levels of credential completion.[3]

In this issue brief, we introduce holistic credit mobility as a framework for making sense of contemporary student mobility and devising solutions that center the success of mobile students with multiple forms and sources of validated learning. In the sections that follow, we define holistic credit mobility and highlight strategies to support its effective deployment throughout postsecondary institutions and systems.

Mobility Matters

Secondary schools, postsecondary institutions, and employers have started down the path of translating more types of learning into transcriptable credits,[4] including dual enrollment, military training, employer-offered training or professional development, and other options. These approaches to learning have created more opportunities than ever for students to earn postsecondary credits and bring them closer to completing a credential. However, when a student moves institutions, they frequently find that they lose ground when they try to apply those credits towards a program of study at the new institution.

People learn through a variety of modalities, including in K-12 schools, colleges and universities, and the workplace.

In some cases, people obtain validated learning when they convert learning into college credit.

Credits are generally earned through taking college courses, whether in-person, online, or through a hybrid format.

According to the Government Accountability Office, transfer students lose an estimated 43 percent of their credits when they move to a new institution.[5] While credit articulation policies are frequently less than generous, these credit losses are exacerbated by the fact that the course transfer process is often remarkably difficult to navigate, suffers from a lack of clear communication, and is inconsistent from student-to-student or from institution-to-institution. The student and the receiving institution are generally left patching together previous learning, while the institution the student exited from has very little role in supporting the transition.

Offering more options for how and where students earn credits is insufficient on its own; students must also be enabled to count those credits toward a credential of value.

Transfer credit loss and difficulties in navigation are sufficient cause to revisit transfer policy and practice. And, course transfer is not the only situation where mobility disadvantages students seeking postsecondary credentials. Students who participate in dual enrollment in high school, competency-based assessments, prior learning assessments, portfolios, or other options generally face unclear and inconsistent policies and may find that their learning is not consistently accepted across institutions. In sum, offering more options for how and where students earn credits is insufficient on its own; students must also be enabled to count those credits toward a credential of value.

Failure to attend to the realities of a mobile student population has consequences for individual completion and for nationwide attainment. In the sections that follow, we present a new conceptual framework for how institutions, systems, and policy leaders can better serve mobile students: holistic credit mobility.

Holistic Credit Mobility

Numerous researchers and policy organizations have called for postsecondary institutions to allow learning done outside of their own classrooms to count towards students’ desired credentials. Many of these studies focus on one specific credit accumulation modality rather than looking at them globally—for example, prior learning assessment,[6] credit by exam,[7] course transfer,[8] dual enrollment,[9] or military or corporate training.[10] Existing research has also been slow to consider the impact of student mobility on how learning completed outside of the classroom is assessed and applied towards a student’s degree plan.

Holistic credit mobility embraces the multi-source, multi-modal credit accumulation of mobile students, and empowers those students to chart a path that counts all their learning toward a credential.

In contrast, holistic credit mobility embraces the multi-source, multi-modal credit accumulation of mobile students, and empowers those students to chart a path that counts all their learning toward a credential. To accomplish this, holistic credit mobility shifts the perspective to center learning as the determining factor in credential completion. Rather than focusing exclusively on inputs, holistic credit mobility centers the output—student learning—as the most important determinant in student progress towards their credential. When institutions embrace holistic credit mobility, students know how validated learning from any source will count toward credential requirements before they enter a postsecondary institution. Students will not have to repeat successful, validated learning along their journey. Finally, students are advised and supported in charting a learning pathway from wherever they are to the credential they seek.

When postsecondary institutions center learning, they begin with the question: “What learning happened?” The answer to that question drives the evaluation of the student’s experiences and how they can apply towards the desired credential. Centering learning also necessitates a more expansive view of how students can gain the experiences that they still need to earn their credential. While classroom, online, or hybrid coursework may be needed, the institution may also support and encourage students to make additional progress towards their credential by leveraging other ways to demonstrate learning.

Holistic Credit Mobility centers learning first by:

- Counting validated learning regardless of source

- Avoiding repeated learning of the same content

- Requiring inter-institutional collaboration

- Including student advising on what credit is accepted as well as what learning is still required to earn desired credential

Holistic credit mobility also rejects the notion that repeating successful learning is acceptable. As students with work and life experiences navigate postsecondary systems, it is not uncommon for content that was gained on the job to be repeated in the classroom, either for all or part of entire courses. Rather than using credential requirements against students with policies that require entire courses to be repeated, or letting good-but-not-perfect course equivalencies hold students back, centering learning means that institutions accept that there may be more than one way to the finish line.

Finally, holistic credit mobility requires postsecondary institutions to work together in new ways. As it is currently constructed, moving between institutions before completing a credential is generally regarded as something to avoid—even though 64 percent of Bachelor’s degree completers who began in the 2014-15 academic year earned credits at more than one institution before completing.[11] Students generally accept that they will likely lose progress in the process, thus presenting students with unnecessarily complicated choices when their life circumstances require mobility. While practices like reverse transfer attempt to correct for this, they only address the share of students that managed to successfully navigate vertical transfer. Greater degrees of institutional cooperation within and across systems may support a new view of student mobility—one where it is not a disadvantage, but an accepted trait of today’s students that must be accounted for in ways that still support timely completion.

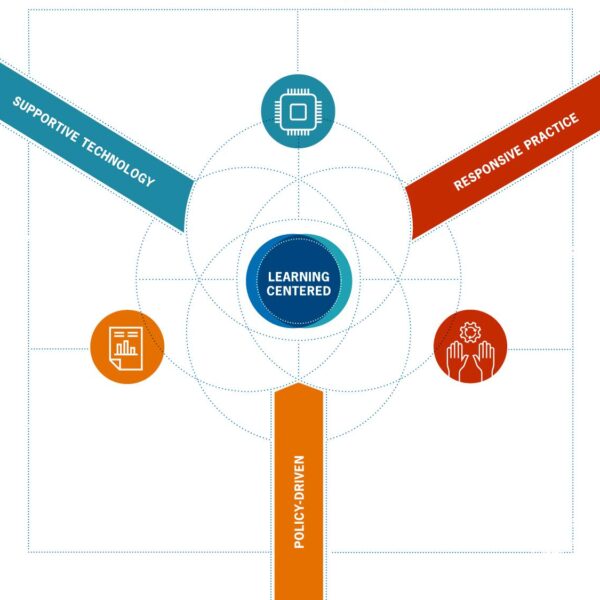

In the sections that follow, we dive into three necessary supports for more holistic credit mobility—technology, policy, and practice—to explore and define ways that systems and institutions can grow to better support student mobility.

Necessary Supports for Holistic Credit Mobility

To successfully move towards holistic credit mobility, institutions, systems, and states must address three necessary supports: supportive technology, policy, and responsive practice.

Supportive Technology: Currently, there is inconsistent or insufficient technological development to support reconciling learning from multiple sources, and the technologies that do exist are limited and fragmented.

Policy-Driven: State policy is generally quiet when it comes to institutional approaches to reconciling learning from multiple sources, resulting in a patchwork of institutional policies that compromise student mobility. Policy has also been slow to attend to the financial disincentives that institutions face in the credit assessment and acceptance process.

Responsive Practice: Limited support to students who have withdrawn or stopped out, insufficient or ineffective student advising to encourage exploration of ways to gain credits outside of the classroom, and unclear pathways for moving between institutions all represent problems in practice at the institutional or cross-institutional level.

Developing and applying a holistic credit mobility framework may begin the process of solving these challenges. Not only does a holistic view tie together each of the various modalities available to students for credit accumulation, it also centers the mobility and flexibility that people seek as we emerge from the peaks of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Importantly, these three supports to holistic credit mobility are overlapping and work in concert to provide learners with more integrated and streamlined credentialing opportunities. Deploying technological tools is no substitute for responsive practice, and vice versa. Meaningful policy may be an underlying driver to efforts in the other two areas. The framework is intended to be used integratively, and not to separate efforts that are inherently mutually reinforcing.

In the sections that follow, we discuss each of these potential supports to holistic credit mobility in more detail and provide examples of promising actions from the field.

Supportive Technology

Technological tools can support mobile students by providing information to support their institutional choice and forward-looking planning. While effective academic advising is a necessary complement to technological interventions, putting information about how previous educational experiences are assessed in the transfer process in a broadly accessible, reliable, and customizable tool allows students to self-assess and plan what may be needed to bring them closer to completing their credential.

Technological solutions related to learning assessment and credential progress exist on a broad spectrum from relatively simple websites that display course transfer libraries to tools that assess course descriptions to create equivalencies in real time,[12] systems that match completed learning to the most efficient credential option, or blockchain-based systems where students keep track of their own learning in a digital wallet.[13] Some tools are proprietary, while others are more broadly accessible. The field is constantly developing, which necessitates an ongoing assessment of institution, system, and state-level tools and the extent to which they are providing the intended outcomes.

Tools that can support students in understanding how their previous or future educational experiences can bring them to a credential most efficiently are key. Tools should also be responsive to the audience that they intend to reach. While transfer course libraries are helpful, this type of user interface may be easier for a skilled academic advisor to navigate versus a current or prospective student who is less familiar with the requirements to complete their desired credential.

No technological solution will completely correct for the challenges to embodying a holistic approach to credit mobility. However, putting technological interventions in place that can provide timely, reliable, and understandable information in the reach of students and advisors is a key step.

![]()

Policy-Driven

The majority of formal policy related to credit mobility rests at the institution and system levels, with states providing supportive guidance in legislation, regulation, or via memorandums of understanding between systems or subsets of institutions.[14] By and large, policy approaches are disproportionately focused on vertical transfer—ensuring that students who begin their postsecondary pathway in a two-year college are able to successfully navigate to and complete a four-year degree in a college or university. Even with more robust policy focused on improving vertical transfer, the share of students that successfully navigate the pathway is small: while 80 percent of students in community colleges aspire to earn a bachelor’s degree, 31 percent will successfully transfer, and only 14 percent of those students will earn a bachelor’s degree within six years.[15] Policy addressing other types of student mobility—for example, four-year to four-year transfer, student mobility across state lines, gaining credit for learning done outside of the classroom, or providing credit-by-exam across institutions, is much less developed.

State- and system-level policy leaders may have an opportunity to act in two key ways to support holistic credit mobility. First, current institutional and state-level governance structures were not always designed with the type of collaboration needed to advance a holistic credit mobility framework. To correct for this, some states and systems have created cooperative groups and task forces between two- and four-year institutions to support vertical transfer policy development. Fewer such groups exist to support collaboration in considering a wider array of policies that implicate mobile students. Bringing a wider array of stakeholders to the table to improve experiences for mobile students—namely, high schools, four-year institutions, and employers may lead to greater levels of cohesion and cooperation across sectors.

Second, policy leaders may consider the financial incentives and disincentives that postsecondary institutions face when it comes to granting credit for learning done outside of their particular classrooms. In some jurisdictions, incentives can exist for two-year colleges to prepare students for successful transfer, but fewer financial incentives exist for four-year institutions to accept those students with all of their earned credits. Far fewer incentives exist for institutions to take a holistic approach to evaluating the totality of student learning and maximizing application of that learning towards a credential. In postsecondary systems that are increasingly tuition dependent, the financial disincentives to institutions providing holistic credit mobility may be relieved through public policy intervention.

Responsive Practice

Technology and policy changes alone will not be enough to move people and institutions towards a more holistic approach to credit mobility—practices must also respond. While policies can set guideposts, implementation and integration into daily practice is what will ultimately impact students. Several current common practices at the institution and system levels that preclude holistic credit mobility include limited support for students who have withdrawn, lack of capacity for academic advising, and unclear inter-institutional pathways.

Mobile students may be faced with situations that necessitate withdrawing from the term or program in which they are enrolled. While transitions would ideally line up with the end of the course or term, the reality is that this may not be possible in all situations. When students withdraw partway through the term, they are generally faced with a barrage of processes depending on the point in the term in which they withdraw. Reforms in federal and state policies impacting mobile students—such as Return to Title IV funds (R2T4) and Satisfactory Academic Progress (SAP)—could certainly further support mobile students. And, even absent these reforms, there may be space for institutions to act to better support students that are faced with not completing the term they initially intended to finish. This could include efforts like proactively providing students with transfer options in the region, providing unique supports for students that might owe a balance to the institution, or planning in advance for the student’s re-entry in a future term.

Students that intend to bring in credit and learning from other institutions also have specific and unique advising needs. However, high advisor to student ratios have been prevalent in many postsecondary institutions for a considerable amount of time. Constrained capacity on the advising side likely contributes to prospective students not having access to advising prior to admission, slower times to review students’ prior transcripts and learning, and students pursuing inefficient credential plans without first consulting an advisor. Absent additional advising capacity, students coming into institutions with previous learning experiences need other ways to ensure that no stone is left unturned in assessing their prior learning and experiences towards their desired credential.

Finally, postsecondary institutions—especially those located in the same geographic regions—should shift practices to assume student mobility rather than avoid it. Whether or not institutions proactively communicate and set up course and learning equivalencies, students within the region are likely moving between their institutions. Rather than leaving students to navigate these trajectories on their own, institutions on both the sending and receiving end will better support greater levels of system- or state-wide enrollment by supporting mobile students. Creating inter-institution communication channels where they may not exist and supporting and maintaining that communication is key to supporting holistic student mobility.

Putting Holistic Credit Mobility into Practice

Creating a more holistic vision for credit mobility can be supported by technology, policy, and practice. However, for the concept of holistic credit mobility to have impact, it must be translated into action. In the sections that follow, we illustrate how institutions and systems that have leveraged at least one of the three supports for holistic credit mobility in their approach to better serving mobile students.

Transfer Explorer

Transfer Explorer, co-developed by Ithaka S+R and the City University of New York (CUNY), is a publicly accessible website displaying easy-to-navigate, real-time data on how any course taken at any CUNY college will be treated if a student transfers to any other CUNY college.[16] In just two years, Transfer Explorer has become a critical piece of CUNY’s transfer infrastructure, with over 64,000 unique users accessing the site since May 2020. In addition to serving as an informational resource to prospective transfer students and their advisors, a group of eight CUNY institutions has formed a community of practice to utilize the public site and additional feature prototypes to inform changes in transfer policy and processes. Examples include speeding up the process of transcript evaluation, facilitating the creation and updating of articulation agreements, proactively setting and monitoring student transfer intention plans, and intervening to help new transfer students choose the most efficient course registrations at their destination college. During the project, the community of practice colleges have seen notable improvements in outcomes such as the time between transfer admission and course evaluation and the share of transfer students able to count all of their credits toward their new degree.[17]

Other features under development include functionality for users to see how transferred courses count toward any degree program at any CUNY college, the ability for users to create and monitor a transfer plan, details on the outcomes of transfer students at each of CUNY’s colleges, and the inclusion of information on how CUNY colleges treat credits or validated learning earned outside of CUNY. The Transfer Explorer team also has plans to expand or replicate the site to other higher education institutions and state systems.

Transfer Explorer demonstrates holistic credit mobility because it leverages a technological solution to make authoritative, real-time course equivalency and degree applicability information broadly accessible.

Transfer Explorer demonstrates holistic credit mobility because it leverages a technological solution to make authoritative, real-time course equivalency and degree applicability information broadly accessible. The tool is also scaled across the entire system, connecting institutions that often share students. Finally, as a public site, the tool is designed to meet students’ information needs, whether they have applied for admission or not. Any user can learn how credits earned at any CUNY institution—and soon, any credits earned anywhere evaluated by a CUNY institution—will count toward degree program requirements at other CUNY institutions.

Oregon House Bill 4059

Over the last ten years, lawmakers in Oregon have leveraged policy to improve credit mobility across the state. In 2012, H.B. 4059 instructed the HECC and State Board of Higher Education to increase the number and type of academic credits accepted for prior learning through more transparent institutional policies and practices.[18] Five years later in 2017, H.B. 2998 addressed transferability for credits earned through prior learning by establishing a foundational curriculum with credits that would transfer and count towards degree requirements at four-year public institutions as well as developing a unified statewide transfer agreement for each major course of study.[19] Finally, in 2021, S.B. 233 established a Transfer Council tasked with developing a common course numbering system and Major Transfer Maps.[20]

In addition to efforts to reform prior learning and transfer policies, Oregon has also taken steps to align funding incentives to better serve mobile students. Through HECC’s Student Success and Completion Model, the state’s seven public universities can receive funding increases for transfer students completing degrees on their campuses.[21]

Oregon’s funding policies incentivize four-year institutions to enroll and support mobile students by providing funding increases when they complete credentials.

Oregon’s policy-driven efforts to create transfer pathways leverages holistic credit mobility in several ways. First, the policies address not only classroom learning but also credit earned through prior learning assessment. Additionally, Oregon’s policies support inter-institutional communication through the Transfer Council. This type of collaboration will hopefully continue to ensure that mobile students are not disadvantaged when they move between institutions in Oregon. Finally, Oregon’s funding policies incentivize four-year institutions to enroll and support mobile students by providing funding increases when they complete credentials.

Maryland House Bill 460

Similar to Oregon, the state of Maryland has used policy to drive support for mobile students, with an angle towards accountability. Enacted in 2021, Maryland H.B. 460 requires public postsecondary institutions to report when they deny an enrolled student’s transfer credit or course. This report is sent to the student and to the institution where the credit was earned. Annually, each institution is required to provide a report of the courses they have denied for transfer to the Maryland Higher Education Commission. This policy may place pressure on receiving institutions to accept more credits for incoming transfer students.

Previous legislation from 2013 required the Commission to establish a statewide transfer agreement where at least 60 credits earned at any state community college are guaranteed to transfer to any public four-year institution. Lastly, the Commission was required to collaborate with public postsecondary institutions in Maryland to implement a statewide reverse transfer agreement where at least 30 credits from a four-year public institution could be transferred to a community college to award an associate’s degree.[22]

Maryland’s recent efforts illustrate holistic credit mobility by leveraging policy to encourage institutions to accept credits and providing an accountability incentive to accept credits.

Maryland’s recent efforts illustrate holistic credit mobility by leveraging policy to encourage institutions to accept credits and providing an accountability incentive to accept credits. The state is also focusing on expanding efforts past vertical transfer to include reverse transfer.

WICHE Interstate Passport

The Western Interstate Compact for Higher Education, or WICHE, brings members together to support higher education systems and collaboration across the western United States. Part of their efforts include student mobility and transfer, including work on the Interstate Passport, a national program which enables seamless block transfer of lower division courses based on multi-state, faculty-developed learning outcomes instead of a specific set of courses and credits. Through the program, students demonstrate competencies for a block of lower-division general education courses, earning an Interstate Passport that they can take to any of the member institutions. Though courses may not have one-to-one equivalencies across institutions, students are guaranteed that the credits they have earned will be accepted in network institutions. The Interstate Passport also provides students with a simple way to take credits out of an institution, if the institution is a part of the Interstate Passport network.

Though courses may not have one-to-one equivalencies across institutions, students are guaranteed that the credits they have earned will be accepted in network institutions.

The Interstate Passport is one of relatively few examples of course mobility that crosses state borders. While examples from Oregon and Maryland demonstrate the use of policy to support transfer within their borders, the Interstate Passport allows students to take their learning across participating institutions, regardless of whether they are located within the same state. The passport centers student learning completed rather than preferencing the state in which the learning was done.

Course Sharing

Increasingly, institutions are looking to course sharing to (re)align their course capacity with enrollment. Through course sharing, institutions can offer excess capacity in their own offerings to students enrolled in other institutions.[23] Institutions agree to fully accept one another’s courses and may even allow students to complete entire majors through peer institutions.

For example, the HBCU-MSI Course-Sharing Consortium is a collaboration designed to support students at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) and Minority-Serving Institutions (MSIs) on their pathways to on-time graduation.[24] Students who need specific courses to fulfill requirements can do so at member institutions through online courses that can be found through the course-share platform, powered by Acadeum. This collaboration increases course availability for students, who can enroll in the courses without any disruption to the way their GPAs are calculated, their financial aid, or their graduation requirements at their home institutions.[25]

While initially conceived as a way for institutions to open up excess course capacity to students enrolled in other postsecondary institutions, course sharing may also have potential to serve mobile students well.

While initially conceived as a way for institutions to open up excess course capacity to students enrolled in other postsecondary institutions, course sharing may also have potential to serve mobile students well. For example, students may find that maintaining most of their enrollment in their home institution can be complemented through course shares at other peer institutions that might offer course content, timing, or delivery models that better align with their needs. In this way, course sharing eliminates the need for many of the impediments generally associated with traditional course transfer, such as articulation agreements, sharing transcripts, and risking that your institution chooses not to accept the credit at the end of the term. Through course sharing, these steps are moved behind-the-scenes, thus streamlining processes for students.

Ensuring Quality

Holistic credit mobility centers successful student learning as the determining factor towards credential completion, and can be supported by technology, policy, and practice innovations. However, this simple definition risks masking some of the real challenges to implementation, especially when it comes to ensuring quality.

Accreditation requirements, or the interpretation of those requirements, may present impediments to accepting and applying more credits and types of learning towards credentials. Generally, accreditors seek to ensure institutions or specific programs are meeting quality standards. However, there is work to be done when it comes to ensuring quality while still responding to the needs of mobile students. Generally, accreditors may be able to do more to clarify ways institutions can apply previous learning towards credentials without compromising their accreditation status.

Faculty have limited access to the information that they may need to assess student learning and to accurately place a student on a pathway to completion.

Competing priorities and incentives for faculty can present a second challenge to implementing holistic credit mobility. This is not because faculty are unsupportive of making sure students have clear throughlines to credential completion, but because they are at the intersection of at least three competing priorities: (1) the institution, which may face financial disincentives to the acceptance of learning from other places, (2) the student, who presumably would like to complete their credential as efficiently as possible, and (3) their field, which relies on faculty to ensure a minimum level of competency across all newly-trained graduates. Currently, faculty have limited access to the information that they may need to assess student learning and to accurately place a student on a pathway to completion. Official transcripts tell one part of the story, while course syllabi, learning portfolios, and other materials should also be brought to bear. Adding to these limitations, faculty are not often called to review student learning until after the student is admitted and perhaps even committed to attending the institution. Supporting faculty to ensure they can implement a holistic credit mobility framework within and across institutions is key.

Taken together, both accreditors and faculty have key roles to play in ensuring the quality of the credentials that postsecondary institutions produce. And, to be sure, ensuring this quality becomes more difficult when student learning is dispersed across different places. Facing the challenge of ensuring quality will be key to better serving mobile students and enacting a holistic credit mobility framework.

Conclusion

Over half of students today gain learning through multiple modalities and in multiple places on their way to a postsecondary credential.[26] However, student mobility can place significant barriers to postsecondary success and completion. In this issue brief, we make the case that successful learning should bring a student closer to completion, and that the people and systems that assess and award credentials should take a more holistic approach to applying that learning. Technological tools can support this assessment, but must be accessible, accurate, scaled across systems of institutions, and mindful of the audience they intend to reach. Public and higher education policy can also support holistic credit mobility by expanding its focus beyond vertical transfer, supporting inter-institutional collaboration, and attending to funding models that disincentivize institutions to work with mobile students. Practice reforms related to learning and credit evaluation can also bring institutions closer to embracing holistic credit mobility.

In some institutions, systems, and states, technological innovation, policy reform, and practice changes are in process and center the needs of mobile students. These include efforts to provide prospective transfer students with accurate information about their options, statewide approaches to streamlining institutional responses to prior learning and course transfer, acceptance of credit across state lines, and course sharing. Continuing these and other related reforms is necessary if postsecondary education is to collectively meet the growing needs of today’s mobile students.

Endnotes

- Doug Shapiro, Afet Dundar, Phoebe Khasaiala Wakhungu, Xin Yuan, Angel Nathan, and Youngsik Hwang, Time to Degree: A National View of the Time Enrolled and Elapsed for Associate and Bachelor’s Degree Earners (Report no. 11), Herndon, VA: National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, September 2016, https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/SignatureReport11.pdf. ↑

- Ibid.↑

- Sara Goldrick-Rab and Fabian T. Pfeffer, “Beyond Access: Explaining Socioeconomic Differences in College Transfer,” Sociology of Education 82, no. 2 (2009): 101–25, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40376041. ↑

- For example: “About Learning Evaluations,” American Council on Education, accessed 20 September 2022, https://www.acenet.edu/Programs-Services/Pages/Credit-Transcripts/About-Learning-Evaluation.aspx. ↑

- “Higher Education: Students Need More Information to Help Reduce Challenges in Transferring College Credits,” US Government Accountability Office, 13 September 2017, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-17-574. ↑

- See, for instance, Rosa M. Garcia and Sarah Leibrandt, “The Current State of Higher Learning Policies,” Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education and the Center for Law and Social Policy, accessed 20 September 2022, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED611043.pdf, and Mary Beth Lakin, Christopher J. Nellum, Deborah Seymour, and Jennifer R. Crandall, “Credit for Prior Learning: Charting Institutional Practice for Sustainability,” American Council on Education, 2015, https://www.acenet.edu/Documents/Credit-for-Prior-Learning-Charting-Institutional-Practice-for-Sustainability.pdf. ↑

- Angela Boatman, Michael Hurwitz, Jason Lee, and Jonathan Smith, “CLEP Me Out of Here: The Impact of Prior Learning Assessments on College Completion,” Andrew Young School of Policy Studies, November 2017, https://aysps.gsu.edu/download/clep-me-out-of-here-the-impact-of-prior-learning-assessments-on-college-completion/?wpdmdl=6489056&refresh=62fe3bdb8ab001660828635. ↑

- See, for example, “The Transfer Reset: Rethinking Equitable Policy for Today’s Learners,” Tackling Transfer Policy Advisory Board, 26 July 2021, http://hcmstrategists.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/PAB_TransferReset_Full_Final_07_26_21.pdf, and Hans Johnson and Marisol Cuellar Mejia, “Increasing Community College Transfers: Progress and Barriers,” Public Policy Institute of California, September 2020, https://www.ppic.org/wp-content/uploads/increasing-community-college-transfers-progress-and-barriers-september-2020.pdf. ↑

- See, for example, Brian P. An, “The Impact of Dual Enrollment on College Degree Attainment: Do Low-SES Students Benefit?” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 35, no. 1 (2013): 57–75, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23356970, and Matt Reed, “Dual Enrollment and Changing Majors,” Confessions of a Community College Dean, Inside Higher Education, 30 August 2022, https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/confessions-community-college-dean/dual-enrollment-and-changing-majors. ↑

- Stacie Hitt, Martina Sternberg, Shelley MacDermid Wadsworth, Joyce Vaughan, Rhiannon Carlson, Elizabeth Dansie, and Martina Mohrbacher, “The Higher Education Landscape for US Student Service Members and Veterans in Indiana,” Higher Education 70, no. 3 (2015): 535–50, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43648886. ↑

- “COVID-19 Transfer, Mobility, and Progress: First Two Years of the Pandemic Report,” National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, 13 September 2022, https://nscresearchcenter.org/transfer-mobility-and-progress/.↑

- Zachary A. Pardos, Hung Chau, and Haocheng Zhao, “Data-Assistive Course-to-Course Articulation Using Machine Translation,” L@S ’19: Proceedings of the Sixth (2019) ACM Conference on Learning @ Scale, June 2019, 1-10, https://doi.org/10.1145/3330430.3333622. ↑

- For example: Lindsay McKenzie, “Boosting Degree Completion With Blockchain,” Inside Higher Ed, 9 July 2019, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2019/07/09/arizona-state-tackling-college-completion-blockchain; Lindsay McKenzie, “MIT Introduces Digital Diplomas,” Inside Higher Ed, 19 October 2017, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/10/19/mit-introduces-digital-diplomas; Lindsay McKenzie, “Seeking a Shared Global Standard for Digital Credentials,” Inside Higher Ed, 24 April 2019, https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2019/04/24/mit-and-8-other-universities-partner-shared-digital-credential. ↑

- Erin Whinnery and Lauren Piesach, “50-State Comparison: Transfer and Articulation Policies,” Education Commission of the State, 28 July 2022, https://www.ecs.org/50-state-comparison-transfer-and-articulation/. ↑

- See “Tackling Transfer,” Tackling Transfer, accessed 20 September 2022, https://tacklingtransfer.org/, and Rachel Baker, “The Effects of Structured Transfer Pathways in Community Colleges,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 38, no. 4 (2016): 626–46, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44984558. ↑

- Transfer Explorer is available at https://explorer.cuny.edu/. ↑

- Martin Kurzweil, “Turning Credit Transfer From a Black Box Into an Open Book,” Inside Higher Ed, 21 April 2022, https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/beyond-transfer/turning-credit-transfer-black-box-open-book. ↑

- “Enrolled House Bill 4059,” Oregon Legislative Assembly, 2012, http://olis.oregonlegislature.gov/liz/2012R1/Downloads/MeasureDocument/HB4059/Enrolled. ↑

- “Enrolled House Bill 2998,” Oregon Legislative Assembly, 2017, https://olis.oregonlegislature.gov/liz/2017R1/Downloads/MeasureDocument/HB2998/Enrolled. ↑

- “Transfer and Credit Strategies,” State of Oregon: Higher Education Coordinating Commission, https://www.oregon.gov/highered/policy-collaboration/Pages/transfer-credit.aspx. ↑

- “Student Success and Completion Model,” Higher Education Coordinating Commission, September 2019, https://www.oregon.gov/highered/institutions-programs/postsecondary-finance-capital/Documents/Univ-Finance/SSCM-two-pager-2019.pdf. ↑

- “House Bill 460: Transfer with Success Act,” General Assembly of Maryland, 18 May 2021, https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/2021RS/Chapters_noln/CH_188_hb0460t.pdf. ↑

- Jon Marcus, “At the Edge of a Cliff, Some Colleges Are Teaming Up to Survive,” New York Times, 6 October 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/06/education/learning/college-course-sharing.html. ↑

- David Steele, “Joining Forces to Share Courses,” Inside Higher Ed, 10 May 10 2022, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2022/05/10/more-course-sharing-partnerships-help-students-graduate. ↑

- Rebecca Kelliher, “Southern Regional Education Board Launches HBCU-MSI Course-Sharing Consortium,” Diverse Issues in Higher Education, 5 May 2022, https://www.diverseeducation.com/institutions/hbcus/article/15291690/ southern-regional-education-board-launches-hbcumsi-coursesharing-consortium. ↑

- “COVID-19 Transfer, Mobility, and Progress: First Two Years of the Pandemic Report.” ↑