Lost and Found: State and Institutional Actions to Resolve Stranded Credits

Introduction

Nationally, Ithaka S+R estimates that over six million students have completed credits at postsecondary institutions that they cannot document due to a past due balance.[1] These overdue balances contribute to a national problem of stranded credits—credits that students have completed but cannot document because they were unable to fulfill their financial obligations to their institution.

This brief provides a roadmap for stakeholders interested in the underlying practices that create stranded credits and what can be done to improve them. To begin, we provide specific definitions of the terms and practices implicated in the creation of stranded credits. While researchers and policy leaders have increased their attention on the problem of stranded credits, this brief lays out in detail how they are created, why they matter, and what can be done to better balance the interests of institutions, students, and a modern economy that relies on postsecondary education for the development of a competitive workforce.[2]

Types of Institutional Holds

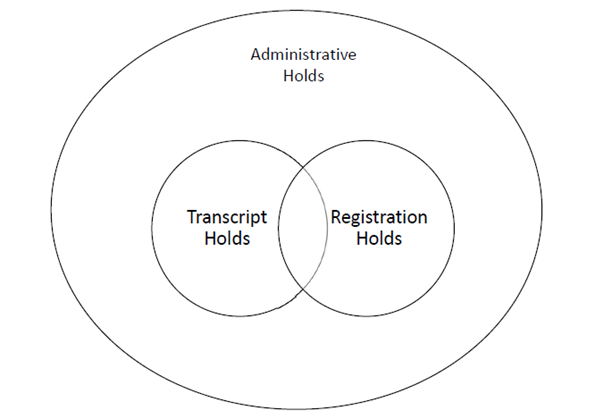

Stranded credits often arise from one or more administrative holds placed on a student’s account. Postsecondary institutions employ a variety of administrative holds in an attempt to force certain student actions or to prohibit students from taking certain actions. Administrative holds are placed in student information system software—either manually by staff or automatically. Often, placing a hold is a last resort after other types of student outreach have failed, such as phone calls, email, texting, or mail.[3] Perhaps ironically, these same types of outreach are also used to notify students that the hold has been placed. In the context of stranded credits, two types of administrative holds are relevant: registration holds and transcript holds.

In this brief, we refer to any hold that would preclude a student from registering for courses as a registration hold. According to a survey deployed by higher education consulting firm EAB, institutions may have anywhere from 40 to 80 different kinds of holds that prohibit a student from registering for new courses.[4] A more recent survey of 14 institutions conducted by the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admission Officers (AACRAO) found over 350 unique hold codes which prevent a student from registering, accessing a transcript, or both.[5] These holds can be placed for academic issues such as failing to declare a major or meet with an advisor, or being in violation of Satisfactory Academic Progress (SAP). Holds can also originate from other non-academic compliance issues, such as failing to document required vaccinations or violating the student code of conduct.

In contrast to registration holds, which almost certainly influence student progress towards their intended credentials, a transcript hold prohibits a student from receiving an official transcript from the institution. Transcript holds can be placed for a variety of reasons; however, a common trigger is failure to pay a balance due to the institution.[6] While a student with a registration hold could still access a transcript and transfer to another postsecondary institution, a student with a transcript hold cannot document any of the learning they have completed, even for terms which are paid in full.

Importantly, students may have both registration and transcript holds on their account simultaneously.[7] In these cases, holds place barriers for students seeking to continue their credential at their current institution or to transfer credits to another institution. Figure 1, below, illustrates the universe of administrative holds and their overlapping nature.

Figure 1. Types of Administrative Holds that Contribute to Stranded Credits.

Importantly, only transcript holds can create stranded credits. Credits are stranded when a student cannot access a transcript to document their prior learning. As illustrated above, however, students may only have a transcript hold, but they may also have both a transcript and a registration hold. Students with only one or both types of holds face different challenges and require different supports to continue their education. Stated differently, there is no one solution that will enable all students in this group to successfully re-enroll. While states and institutions have sought to address holds in a more systematic and student-centered way, these efforts are relatively new and may not address the full scope of the issues at hand.

Policy Actions

Federal

At the federal level, leaders have used public statements to condemn the practice of transcript withholding and allude to interest in reform efforts.[8] While previous guidance that promoted transcript withholding has been archived and is no longer current,[9] the Department of Education (ED) has not issued updated guidance related to transcript withholding policy or practice. As such, federal policy or guidance does not formally address how institutions should handle past due balances or transcript holds. While indicating that previous guidance is no longer current is helpful, there may be space for ED to provide more proactive guidance to institutions. This is especially true in cases where other required ED policies and practices, such as Return to Title IV (R2T4) policy, may contribute to creating stranded credits.[10]

State

While formal federal policy or guidance on the issue of transcript withholding has been scant, state policy on the issue is much more developed.[11]

Most states have adopted ambitious goals related to postsecondary attainment, many of which were developed based on projected workforce needs.[12] Locking students out of continued pursuit of their credential hampers progress towards increased attainment. Given that 47 states are not projected to meet their adopted attainment goals,[13] addressing barriers in postsecondary completion is paramount. To the extent that stranded credits are holding a potential student back from re-enrolling, proactively resolving holds may help more students earn credentials.

Enacted state policies related to transcript withholding address three main areas: (1) whether or not postsecondary institutions should have the ability to withhold transcripts, (2) situations where postsecondary institutions may be required to refer past due debt to another state agency, or (3) whether or not postsecondary institutions have the authority to cancel debts they are owed. State postures on each of these issues can impact reform efforts related to unlocking students’ stranded credits.

Transcript holds

States that have addressed the issue of transcript withholding in legislation and/or regulation lie across a spectrum of responses from outright bans on transcript withholding to requiring transcript holds in law. In selecting a policy response to transcript holds, states are seeking to balance attainment agendas, student needs, and institutional revenue streams with their own unique policy contexts. While many state laws and regulations are silent on the issue of transcript withholding, several are not, and many policies were in place prior to more recent interest in the issue of stranded credits.

The map below illustrates which states have aligned to four main policy positions on transcript withholding:

- Allowing holds: A state law or regulation specifically codifies that postsecondary institutions have the right to engage in transcript withholding.

- Requiring holds: A state law or regulation requires institutions to place transcript holds in certain cases.

- Prohibiting holds: A state law or regulation prohibits institutions from placing holds in certain scenarios, most commonly for seeking employment or for course transfer.

- Silent: No state laws or regulations address transcript withholding.

Figure 2.

Eight states have enacted laws that prohibit or limit the use of transcript holds: California, Colorado, Illinois, Maine, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, and Washington. In addition, in the 2022 state legislative sessions, Connecticut, Oklahoma, and Rhode Island all considered transcript withholding legislation which failed to pass prior to the end of the session. Massachusetts, Missouri, and New Jersey have pending policies under consideration. Finally, Maryland, Minnesota, Virginia, and Washington all have legislative mandates to study the issue and publish their findings and recommendations.

California has perhaps the most strict state law on transcript withholding; it prohibits both public and private postsecondary institutions from withholding a transcript when a student has an unpaid balance.[14] The law in Washington differs slightly by specifying that transcripts cannot be withheld when the requestor needs the transcript for “job applications, transferring to another institution, applying for financial aid, pursuit of opportunities in the military or national guard, or pursuit of other postsecondary opportunities.”[15]

Prohibiting transcript holds for entire systems or states allows students access to official transcripts regardless of whether or not they pay their balance. However, it does not give students or institutions tools or incentives to resolve the unpaid balances, prevent student accounts from entering collections, or address registration holds.

On the other end of the spectrum, policymakers in Louisiana have codified that postsecondary governing boards are to adopt their own policies related to transcript withholding.[16] In Alaska, administrative code gives institutions the latitude to withhold transcripts to collect on financial obligations.[17] Two states—Florida and Tennessee—have enacted policies requiring that institutions place transcript holds in certain scenarios. Tennessee Code § 49-7-166 (2019) authorizes state universities to issue transcripts and diplomas only after students have fulfilled all financial obligations to the institution of $100 or more.[18] In the event that a student was paid state-funded grants or loans that subsequently need to be returned, Florida law requires transcript holds.[19]

Debt referral

Four states—Louisiana, New York, Ohio, and Virginia—allow or require public postsecondary institutions to refer past due balances to state agencies tasked with debt collection, such as the Office of the Attorney General or the Department of Revenue.[20] In these cases, institutions may or may not still place a transcript hold, but they are allowed to or required to report overdue debts to the state.

Using these state-level debt recovery approaches may produce some operational efficiency for public institutions and may provide one centralized place for states to track information about past due accounts for public postsecondary institutions. While little is known about how collection practices may differ in state agencies versus private collection agencies, it is possible that there could be differences that have meaningful implications for institutions that are owed debts and for the affected students.[21]

However, requiring debt referral within a certain number of days or if a debt exceeds a certain threshold may also be limiting for institutions that are seeking to actively work with students that have overdue accounts. Since students with past due debts are more likely to be low-income students,[22] referring to state agencies with the authority to garnish other state benefits or intercept tax refunds may exacerbate the financial difficulties that people with past due tuition balances likely already face.

Authority to cancel debts

Finally, not all postsecondary institutions have the authority or flexibility to (re)negotiate or waive debts that are owed to them. State or system-level policies may limit flexibility to re-negotiate or cancel debts. Institutions may also have limited ability to adjust debts they are owed once the debts have been referred to another party to collect, whether that is a state agency or a private collections agency.

Creating smoother pathways to credential completion is a priority that is possible to balance with other institutional priorities.

Creating smoother pathways to credential completion is a priority that is possible to balance with other institutional priorities. As public institutions of higher education become increasingly tuition-dependent,[23] they will seek leverage points to reconcile accounts receivable in a timely manner. Their ability to do so not only impacts revenue in the short-term, but may also impact longer-term financial operations such as issuing bonds, their ability to repay debts, and the cost at which institutions can borrow. Given increased interest in transcript withholding among policymakers, postsecondary institutions may seek options to proactively reform more student-centered transcript withholding processes.

Institutional-Level Reforms

Depending on their size, postsecondary institutions may have anywhere from one to many staff members devoted to billing and receiving tuition payment. Often, these offices are staffed with people that may or may not see themselves as student affairs professionals but are primarily tasked with receiving payment on student accounts due to the university. In the cases when payment is not received on time and in full, postsecondary institutions face an array of inefficiencies and challenges.

First, valuable staff time is directed towards reaching students and counseling them on their options. Those options may include adjusting their course schedule, signing up for a payment plan, or using other options that may be unique to the institution, such as institutional loan or forgiveness programs. In cases where outreach to the student is not effective, institutions place holds and may or may not refer accounts to collections agencies. Evidence from Ohio indicates that once a student account is referred to collections, institutions can expect to receive as little as seven cents on every dollar owed, depending on how long the student has been separated from the institution.[24]

While unpaid balances create inefficiency within the Bursar’s Office, they can also present costly legal issues. Students have sued their institutions over transcript withholding, costing institutions time and money to adjudicate the cases. To date, the outcome of these cases has been mixed, pointing to a risky path forward for both students and institutions that may choose a legal avenue to obtain their transcript.[25] The lack of federal or state policy guidance on the issue of transcript withholding may contribute to the inconsistent determinations happening in courtrooms.[26]

A minority of institutions have responded to these challenges by developing their own programs targeted to provide relief to students with past due balances.[27] These programs may forgive debts or temporarily lend students enough funds to cover the balance. To be clear, these programs can be helpful; however, they may be difficult to scale. What’s more, federal actions related to increased scrutiny of institutionally-funded loan programs may pose challenges to institutions seeking to continue, begin, or expand loan programs.[28]

In sum, the intersection of relatively low return on accounts in collections, coupled with the risk of legal action and increased policymaker interest, points to an opportunity for postsecondary institutions to proactively reform transcript withholding practices. Even in states that have adopted withholding bans, there may still be student-centered ways to move forward with reconciling accounts while also providing immediate access to transcripts, as required by state law.

At a macro level, institutional leaders should (re)examine practices to ensure that they:

- Adapt to the needs of today’s students

- Leverage collaborative communication between campus units

- Cooperate with other postsecondary institutions in the region and state

The first two strategies address practices that could be put into place before the student has left the postsecondary institution. The final strategy proposes a solution for meeting the needs of students with past due balances after they have had a gap in enrollment. The sections that follow introduce each of these guiding principles in more detail.

Adapt to the needs of today’s students

For years, higher education advocates have pointed to the need to center today’s students in policy and in practice.[29] Today’s students engage postsecondary education as only one part of their increasingly complex lives, lives that often include child and/or family care, employment, or other important responsibilities. Often, today’s students provide their own financial support for postsecondary education through a federal and state aid system that risks overestimating how much they can provide for their education expenses and is not required to meet their demonstrated financial need. This system risks placing students in financially precarious positions.

Tuition collection practices should recognize that when a student needs to obtain childcare, pay a medical bill, keep the gas tank full, or ensure that food is on the table for multiple family members, they may need to set unique and equitable payment arrangements.

People that do not have enough money to reliably and consistently meet their basic needs must prioritize, and postsecondary leaders must recognize that tuition payment may not always rise to the top of the list. In sum, tuition collection practices should recognize that when a student needs to obtain childcare, pay a medical bill, keep the gas tank full, or ensure that food is on the table for multiple family members, they may need to set unique and equitable payment arrangements. These arrangements may not result in payment in full by the end of the academic term.

Institutional leaders, if they have not already, should familiarize themselves with the student population that they serve and convene department and unit heads to brainstorm strategies to equitably meet student needs when it comes to billing. Institutions may consider adapting billing practices that align to the needs of today’s students by:

- Reviewing communications for compassion and clarity

- Supporting students in accessing campus, state, and/or federal resources to support their basic needs

- Reviewing a student’s billing in conjunction with their financial aid to ensure the student is receiving all of the aid they are eligible to receive

Leverage collaborative communication between campus units

While institutional staff are often decentralized across functions such as financial aid, billing, and course delivery, students may experience each of these functions in a much more unified way. Students may assume that a financial aid counselor is aware if the student has a past due balance, or that a faculty member may know their financial aid status. Especially in a world that is increasingly automated and consumer-centered, postsecondary institutions can become virtually unnavigable when inter-departmental communication relies on students as an intermediary.

Institutional leaders may review practices related to billing to identify and reform areas where the institution could produce efficiencies to better serve students. This might include:

- More intentional and targeted use of administrative dropping in situations where a student has not engaged in coursework or made payment and the deadline for full tuition refunds is approaching

- Enhanced billing flexibility for students selected for financial aid verification

- Reviewing timelines for tuition refunds together with timelines for R2T4 to narrow the potential window for students to risk returning their aid after withdrawing

Cooperate with other postsecondary institutions in the region and state

Students today are increasingly mobile. They may change their academic plans, the city or region in which they live, or their employment status over the course of earning their postsecondary credential. Historically, this mobility has produced inefficiency. Students may lose tuition dollars and earned credits in the transfer process, they may gain learning through employment that is not recognized and then repeated in the classroom, or they may need to move to a different postsecondary institution to pursue a new credential plan. For institutions, staff must devote time to reviewing transfer credits, gathering course syllabi, and communicating with faculty about student learning.

Registration holds may also unintentionally promote mobility. When a student is unable to register, they may be encouraged to seek out options at another institution rather than resolving the registration hold. This may be especially true for holds placed due to Satisfactory Academic Progress, or SAP, which would not follow a student through the transfer process.

Keeping in mind the larger goal of increasing attainment in a state or region, postsecondary leaders should collaborate to promote re-enrollment of students with registration and/or transcript holds.

While remaining at the same institution to complete a credential is a desirable outcome, it is not always a realistic one. Keeping in mind the larger goal of increasing attainment in a state or region, postsecondary leaders should collaborate to promote re-enrollment of students with registration and/or transcript holds. These arrangements can attend to the barriers that are keeping a student from re-enrolling at the same institution, but also provide flexibility if transferring is the right choice to support the student in completing their credential.

To do so, institutions should:

- Examine data on students that have stopped out with some credits earned but no degree, specifically for patterns in registration and/or transcript holds

- Reformulate unique approaches to student outreach for registration holds and create seamless pathways to lifting registration holds

- Create compacts with other institutions in the region and/or state to share transcripts and settle past due debts in the event that a student re-enrolls at any of the compact institutions

Inter-institutional compacts have the potential to not only allow transcripts to flow freely between participating institutions, but also to resolve the underlying debt, a key component that can protect students’ credit histories and avoid costly collections efforts. Codifying institutional cooperation in a compact model can also formalize pathways and create new opportunities for students seeking options to complete their credential. In Northeast Ohio, eight community colleges are piloting such a solution, with the first class of students enrolling through the compact in the fall of 2022.[30]

Final Thoughts

Now more than ever, postsecondary attainment is being centered as a key strategy to economic competitiveness.[31] However, for many students, the path to a postsecondary credential is increasingly difficult. Transcript holds are major barriers in credential pathways, so major in fact that state and federal policy have taken increased interest in prohibiting or limiting their use. While federal and state policy can be a lever to reform, postsecondary institutions also have the opportunity to lead their own review of policies by adapting to the needs of today’s students, leveraging collaborative communication between campus units, and cooperating with other postsecondary institutions in the region and state. While many roadblocks may stand in the way of completion for some students, taking a proactive approach to resolving the barriers that institutions themselves have placed in students’ paths is a key step in supporting greater levels of student success.

Endnotes

- Julia Karon, James Dean Ward, Catharine Bond Hill, and Martin Kurzweil, “Solving Stranded Credits: Assessing the Scope and Effects of Transcript Withholding on Students, States, and Institutions,” Ithaka S+R, 5 October 2020, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.313978. ↑

-

This issue brief would not be possible without the invaluable research assistance of Alessandra Cipriani-Detres, Ithaka S+R intern.

- “2022 Joint Statement from AACRAO and NACUBO on the Use of Administrative-Process and Student-Success-Related Holds,” NACUBO, 6 April 2022, https://www.nacubo.org/Press-Releases/2022/2022-Joint-Statement-from-AACRAO-and-NACUBO-on-the-Use-of-Holds. ↑

- Ed Venit and David Bevevino, “Student Success Playbook: 14 Recommendations to Improve Student Outcomes and Ensure Financial Sustainability Across the Next Decade,” EAB, 2019, https://www.luminafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/student-success-playbook.pdf. ↑

- Wendy Kilgore and Ken Sharp, “Stop! Do Not Pass Go! Institutional Practices Impeding Undergraduate Student Advancement: Part 1 An Exploratory Study,” AACRAO, https://www.aacrao.org/research-publications/aacrao-research/institutional-practices-impeding-undergraduate-student-advancement-report. ↑

- Ed Venit and David Bevevino, “Student Success Playbook: 14 Recommendations to Improve Student Outcomes and Ensure Financial Sustainability Across the Next Decade,” EAB, 2019, https://www.luminafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/student-success-playbook.pdf. ↑

- Wendy Kilgore and Ken Sharp, “Stop! Do Not Pass Go! Institutional Practices Impeding Undergraduate Student Advancement: Part 1 An Exploratory Study,” AACRAO, https://www.aacrao.org/research-publications/aacrao-research/institutional-practices-impeding-undergraduate-student-advancement-report. ↑

- For example: Kirk Carapezza, “Education Secretary, College Leaders Want Colleges to Stop Holding Transcripts Over Unpaid Balances,” WGBH, 21 December 2021, https://www.wgbh.org/news/education/2021/12/21/education-secretary-college-leaders-want-colleges-to-stop-holding-transcripts-over-unpaid-balances. ↑

- CB 98-13, archived here: https://fsapartners.ed.gov/knowledge-center/library/dear-colleague-letters/1998-10-08/cb-98-13-letter-provides-information-concerning-assignment-defaulted-federal-perkins-loans-and-national-direct-or-defense-student-loans-ndsls-us-department-education-ed-collection. ↑

- When a student attends for less than 60 percent of the academic term in which they were enrolled, their institution must perform a Return to Title IV (R2T4) calculation to determine the portion of disbursed and non-disbursed aid the student earned and the portion that may need to be returned to ED. R2T4 calculations that result in the student owing back a portion of the aid they already received create balances due and risk creating transcript withholding scenarios. ↑

- Julia Karon and James Dean Ward, “A State-by-State Snapshot of Stranded Credits Data and Policy,” Ithaka S+R, 4 May 2021, https://sr.ithaka.org/blog/a-state-by-state-snapshot-of-stranded-credits-data-and-policy/. ↑

- “Stronger Nation: Learning Beyond High School Builds American Talent,” Lumina Foundation, 2022, https://www.luminafoundation.org/stronger-nation/report/#/progress. ↑

- James Dean Ward, Jesse Margolis, Benjamin Weintraut, and Elizabeth Davidson Pisacreta, “Raising the Bar: What States Need to Do to Hit Their Ambitious Higher Education Attainment Goals,” Ithaka S+R, 13 February 2020, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.312647. ↑

- California Assembly Bill 1313, https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200AB1313. ↑

- Washington House Bill 2513, https://lawfilesext.leg.wa.gov/biennium/2019-20/Pdf/Bills/Session%20Laws/House/2513-S2.SL.pdf?q=20210503143523. ↑

- Louisiana policy: RS 47:1676- Debt. ↑

- 20 AAC 17.080, http://www.akleg.gov/basis/aac.asp#20.17.080. ↑

- Tennessee Board of Regents Policy 4.01.03.00, https://policies.tbr.edu/policies/payment-student-fees-enrollment. ↑

- Fl Stat Tit. XLVIII, Ch 1009.95. ↑

- Louisiana policy: RS 47:1676- Debt; the New York Student Recoveries Unit recovers tuition and fees due to SUNY institutions, see: https://legis.la.gov/Legis/Law.aspx?d=861189; Ohio policy: ORC 5747.12 and OAC 5703-7-13; Virginia policy: VA Stat § 2.2-4800. ↑

- For an example from Ohio, see: Piet van Lier, “Collecting Against the Future,” Policy Matters Ohio, 20 February 2020, https://www.policymattersohio.org/research-policy/quality-ohio/education-training/higher-education/collecting-against-the-future. ↑

- Sosanya Jones and Melody Andrews, “Stranded Credits: A Matter of Equity,” Ithaka S+R, 17 August 2021, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.315765. ↑

- State Higher Education Finance Survey, State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, 2020, https://shef.sheeo.org/. ↑

- Piet van Lier, “Collecting Against the Future,” Policy Matters Ohio, 20 February 2020, https://www.policymattersohio.org/research-policy/quality-ohio/education-training/higher-education/collecting-against-the-future. ↑

- Rebecca Maurer, “Withholding Transcripts: Policy, Possibilities, and Legal Recourse,” Student Borrower Protection Center Research Paper, 15 November 2018, available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3288837 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3288837. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Several of these programs are detailed in an earlier Ithaka S+R brief: Julia Karon, James Dean Ward, Catharine Bond Hill, and Martin Kurzweil, “Solving Stranded Credits: Assessing the Scope and Effects of Transcript Withholding on Students, States, and Institutions,” Ithaka S+R, 5 October 2020, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.313978. ↑

- “Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to Examine Colleges’ In-House Lending Practices,” CFPB, 20 January 2022, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/consumer-financial-protection-bureau-to-examine-colleges-in-house-lending-practices/. ↑

- “Today’s Students,” Higher Learning Advocates, https://higherlearningadvocates.org/policy/todays-students/. ↑

- Martin Kurzweil, “A Sustainable Solution to Settle Students’ Debt and Release Stranded Credits,” Ithaka S+R, 8 December 2021, https://sr.ithaka.org/blog/a-sustainable-solution-to-settle-students-debt-and-release-stranded-credits/. ↑

- “Stronger Nation: Learning Beyond High School Builds American Talent,” Lumina Foundation, 2022, https://www.luminafoundation.org/stronger-nation/report/#/progress. ↑