Organizing Support for Success

Community College Academic and Student Support Ecosystems

Introduction

The Community College Academic and Student Support Ecosystems (CCASSE) project examines how academic and student support services at not-for-profit associate-degree granting colleges are organized, funded, and staffed, and how these services can most effectively advance student success. In spring 2019, we surveyed 249 chief academic and student affairs officers at community colleges across the United States on success measures, services offered, resource challenges and constraints, and vision for future service provision.

Key Insights

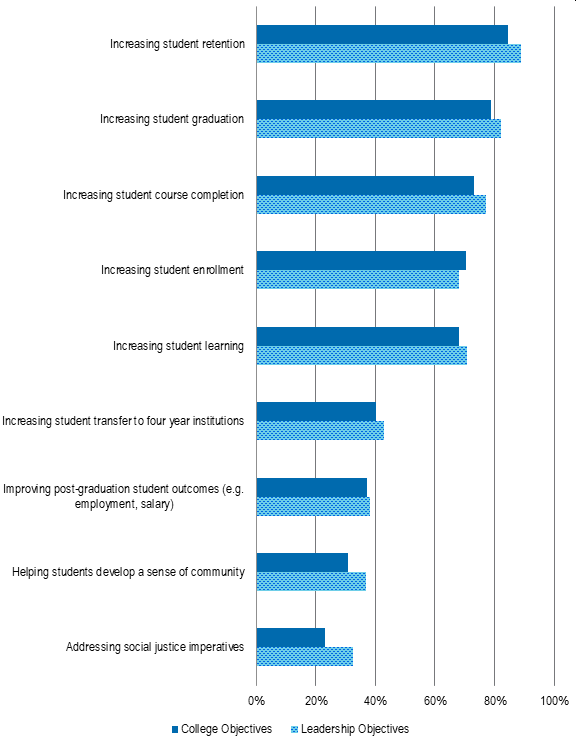

- The most important objectives for colleges and their leaders are increasing student retention, graduation, and course completion. More than seven in ten senior administrators rated increasing student retention, graduation, and course completion as the most important objectives to their college and to the services under their own leadership.

- Services within academic affairs focus more often on student learning and outcomes, while services within student affairs focus more on student enrollment and well-being. Academic affairs leaders are more likely to rate increasing student learning and post-graduation outcomes as important for the services under their leadership compared to student affairs leaders, who view increasing enrollment and helping students develop a sense of community as relatively more important.

- Peer to peer mentoring, academic advising, and dual enrollment services vary in their reporting structure across academic and student affairs. While many services are consistent in to whom they report, these three services do not clearly report to a single department and may be led jointly by academic and student affairs.

- Cross-departmental collaboration is expected to increase. Collaboration between academic and student affairs may be integral to service provision in the future, as eight in ten respondents anticipate seeing more collaboration over the next five years.

- Senior administrators name financial constraints and resistance to change as the primary limitations for making desired changes. Approximately seven in ten respondents indicated that the lack of financial resources limits their ability to make desired changes, followed by four in ten who rate general resistance to change among employees and inadequate institutional infrastructure/systems as challenging.

- Reliance on non-governmental funding sources is expected to increase as governmental funding remains stagnant or decreases. About five in ten respondents anticipate student tuition or fees and private gifts to increase over the next five years, whereas about four in ten expect state appropriations to decrease and three quarters expect federal appropriations to stay the same.

- Senior administrators anticipate that the budgets for academic advising and dual enrollment will increase. For many other services, they anticipate budgets will remain the same over the next five years.

- Senior administrators most often collect and analyze data to improve the effectiveness of support services and demonstrate impact. Greater shares of student affairs leaders use data from intra-institutional sources to improve service provision while academic affairs leaders are more prone to examine external data from other institutions or industries to accomplish these objectives.

- The use of learning analytics tools is expected to increase. Over 70 percent of senior administrators, and even greater shares at large colleges in particular, anticipate the expansion of learning analytics tools.

- Many senior administrators anticipate incorporating more diverse course offerings for an array of student needs into their curriculum. Over 70 percent of senior administrators expect courses for workforce students to increase over the next five years and anticipate more distance learning courses in the curriculum.

- Administrators value the student-centered roles of the library. While only about four in ten respondents highly value the role of the library overall, the overwhelming majority of respondents, especially those at transfer-focused colleges, specifically value the library in providing students with access to technology, resources, and spaces.

The CCASSE Project

Community colleges serve a wide range of students, including, but not limited to, returning adult learners, first-generation students, low-income individuals, and underrepresented minorities. We have spent the last two years deeply engaged in a project that focused on how these students define success, what barriers stand in their way of achieving it, and what services might hold promise for helping them overcome these challenges.[1] We heard clearly from students, both via interview and survey, that they face tremendous difficulty navigating college resources and services and would greatly benefit from a deeper understanding of these ecosystems.

Ensuring that students can access support services requires more than just understanding student needs, but being able to translate those needs into accessible and actionable services to help students achieve academic, personal, and professional success.

Ensuring that students can access support services requires more than just understanding student needs, but being able to translate those needs into accessible and actionable services to help students achieve academic, personal, and professional success. The provision of academic and student support services aimed at helping students realize this success varies from college to college, as they are organized or structured in different ways to utilize limited resources effectively. In order to truly understand how best to provide scalable, actionable, and accessible services, it is not only vital to ask students what they need, but to evaluate how services are currently constructed, organized, funded, and staffed.

To that end, we are engaging in an IMLS-funded, multi-year initiative focused on understanding: (1) how services are currently organized, funded, and staffed to address student needs, (2) what type of library services community colleges need in conjunction with other academic and student services, and (3) how the library can best organize itself to develop and sustain programs or services that contribute to the community college’s mission and student success. The Community College Academic and Student Support Ecosystems (CCASSE) project will contribute to these topics through three phases of work:

- Survey of chief academic and student affairs officers. This survey investigated the perspectives of senior community college administrators within academic and student affairs on the value of the services provided at their college, the challenges they face, among other organizational information.

- Site visits. An in-depth examination of community college services through site visits will provide a holistic perspective on how services are currently structured within different community colleges and the extent to which these services are meeting student needs.

- Survey of library directors. This survey will explore perceptions of the library’s role, priorities, resource allocations, and constraints within the community college, and how the library can best meet the needs of students in coordination with the services offered through academic and student affairs.

This report details the findings from the first phase of the CCASSE project, the survey of chief senior administrators in academic and student affairs, which investigates the current structure and provision of services at two-year colleges.

Methodology

The population for this survey is chief academic and student affairs officers at not-for-profit two-year colleges and associate’s dominant four-year institutions across the United States. These senior administrators vary in their role and title and were thus selected based on the qualification of being in the most senior role within academic and student affairs at each college in the sample. Typical titles for academic affairs roles included Chief Academic Officer (CAO), Provost, and Vice President of Academic Affairs, and those in student affairs were often Vice President of Student Affairs (VPSA), Dean of Students, or Dean of Student Success. In an effort to streamline our reporting, we refer to these individuals as chief academic affairs and student affairs officers, academic and student affairs leaders, or senior administrators throughout this report, recognizing that actual underlying titles vary greatly.

As these roles are typically housed in different offices and carry different titles depending on the college, contact information for the sample was hand-gathered anew. This process entailed creating a list of applicable colleges and locating the contact information for the individual via their college’s website, or by calling the college directly.[2]

After iterating with project advisors on survey instrument drafts, the survey was pre-tested in order to ensure that it was understood consistently and clearly across respondents. Six in-depth cognitive interviews were conducted in March 2019 with senior administrators within the survey population.

The survey was fielded between April and June 2019, and distributed under the signatory of Ithaka S+R leadership and relevant professional associations including the League for Innovation and Achieving the Dream. A total of 11 state college associations also promoted the survey.[3] Approximately 2,069 senior administrators received an email invitation to participate in the survey, and 264 completed the survey for an overall response rate of about 13 percent.[4]

The response rate for respondents from for-profit colleges was not comparable to the rest of the sample, and consequently this subgroup was excluded from analysis.[5] Thus, the sample used in this report includes the 249 respondents representing 229 not-for-profit colleges.[6]

On average, the resulting sample of colleges represented by the respondents have a graduation rate of about 27 percent (SD = 14), a full-time retention rate of about 61 percent (SD = 9.64), a part-time retention rate of about 44 percent (SD = 13), and a transfer-out rate for the total cohort of about 19 percent (SD = 8.91).[7] The resulting sample of 249 respondents broke down in the following manner; some of the following subgroups do not amount to the total sample due to a small number of participants not responding to select survey questions:

Title

- Chief Academic Officer, Vice President of Academic Affairs, Provost, or equivalent: 118

- Vice President of Student Affairs, Dean of Students, Dean of Student Success or equivalent: 93

- Vice President of Academic and Student Affairs or equivalent: 26

- Other: 10

Sector of Institution

- Public, 4-year or above: 23

- Public, 2-year: 213

- Private not-for-profit: 11

- Tribal: 8

Size and Setting

- Very small, two-year (<500 FTE students): 17

- Small, two-year (500-1,999 FTE students): 63

- Medium, two-year (2,000-4,999 FTE students): 80

- Large, two-year (5,000-9,999 FTE students): 49

- Very large, two-year (>10,000 FTE students): 26

- Four-year, primarily nonresidential:[8] 12

Undergraduate Instructional Program[9]

- Associate colleges, high transfer:[10] 80

- Associate colleges, mixed transfer/career & technical:[11] 89

- Associate colleges, high career & technical:[12] 52

- Baccalaureate/associates colleges: 12

- Special focus: two-year institution: 6

- No graduate coexistence:[13] 8

Years in Current Position

- 0 to 5 years: 172

- 6 to 10 years: 42

- 11 to 15 years: 15

- 16 to 20 years: 8

- 21 years and more: 11

Acknowledgements

We thank our external advising committee for their expert guidance and support throughout the project:

- Braddlee, Dean of Learning and Technology Resources and Professor, Northern Virginia Community College

- Rosemary A. Costigan, Vice President for Academic Affairs, Community College of Rhode Island

- Mark McBride, Senior Library Strategist, State University of New York

- Karen Reilly, Dean of Learning Support, Valencia College, Orlando, Florida

- Karen A. Stout, President and CEO, Achieving the Dream

We are immensely grateful to Nicole Betancourt who led the administration of the survey, and to Kimberly Lutz and Roger Schonfeld for their input on this report. This project would not be possible without their substantive contributions.

Student Success Objectives

The most important objectives for two-year colleges are increasing student retention, graduation, and course completion: 85 percent of respondents indicated increasing student retention as extremely important to their college, followed by increasing student graduation (79 percent), course completion (73 percent), student enrollment (70 percent), and student learning (68 percent; see Figure 1).

These objectives align somewhat with student goals that Ithaka S+R uncovered in earlier research with students across seven community colleges. Students named educational advancement—graduating with an associate’s degree or moving on to additional education—as important.[14] While only 37 percent of senior administrators rated increasing post-graduation outcomes as extremely important to their college’s objectives, about half of students rate their ability to make more money and advance in their career as an extremely important goal.[15] The top three most important college objectives do not necessarily capture some of the other intrinsic goals students see as highly important, such as developing social skills or a professional network. However, colleges are aligned with students’ most important intrinsic goal—gaining knowledge. About six in ten students rate this as extremely important to their college experience, and about seven in ten senior administrators rate increasing student learning as an important objective to their college.

Academic and student affairs leaders were later asked the same question regarding their own objectives for the services under their leadership. Increasing student retention was most important, with nine in ten rating retention as extremely important, followed by increasing student graduation (82 percent), course completion (77 percent), and student learning (71 percent; see Figure 1).

Figure 1. How important are each of the following objectives to your college and to you for services under your leadership to students?[16] Percent of respondents that indicated each objective as extremely important.

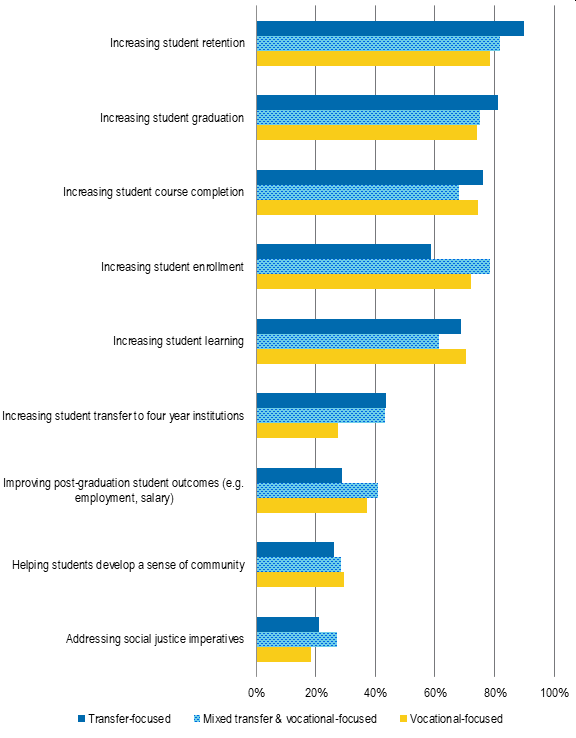

Respondents from large colleges are more concerned with increasing student transfer to four-year institutions, whereas medium and smaller colleges are focused on increasing student enrollment. About 48 percent of respondents from large colleges rated increasing student transfer to four-year institutions as extremely important to their college compared to 38 percent from medium colleges and 35 percent from small colleges. About 72 percent of respondents from medium colleges and 74 percent from small ones rate increasing student enrollment as extremely important, while about 65 percent of respondents from large colleges rate this as important. Additionally, transfer-focused and mixed transfer and vocational-focused colleges rate increasing student transfer as relatively more important than vocational-focused colleges (see Figure 2). However, mixed-focused and vocational-focused colleges rate increasing student enrollment and post-graduation outcomes as more important than transfer-focused colleges.

Figure 2. How important are each of the following objectives to your college? Percent of respondents from transfer-focused, mixed transfer & vocational-focused, and vocational-focused colleges that indicated each objective as extremely important.

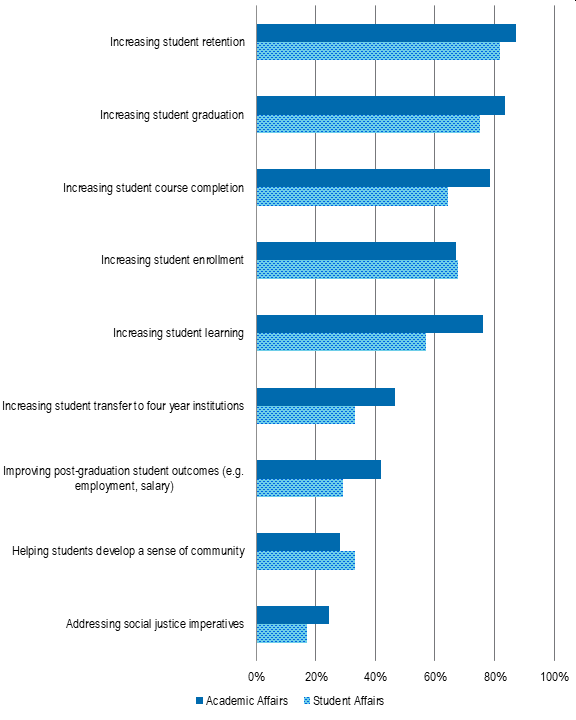

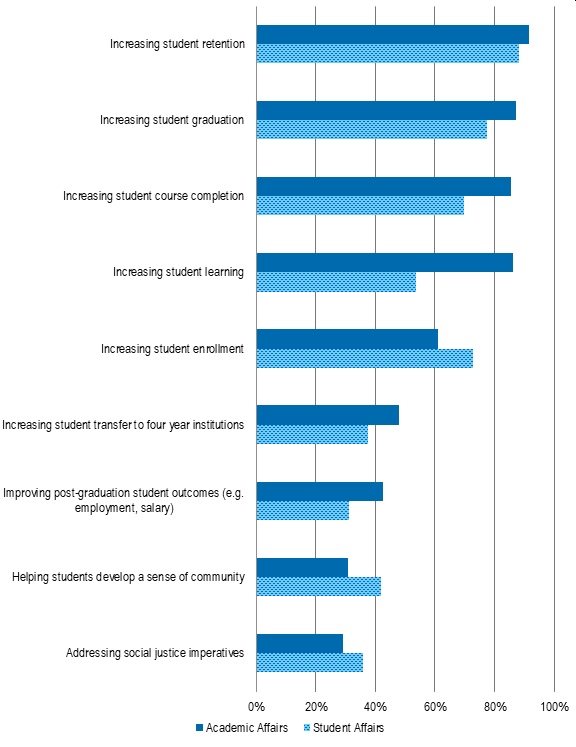

Approximately 76 percent of academic affairs leaders perceive improving student learning to be highly important to their college compared to 57 percent of their colleagues in student affairs. Additionally, leaders in academic affairs designate increasing course completion, transfer to four- year institutions, and post-graduation outcomes to be more important to their college than their colleagues in student affairs (see Figure 3). Similar to what respondents perceive to be important for their college, those in academic affairs rate learning-based objectives (i.e. increasing student learning, course completion) and improving post-graduation outcomes as more important than their colleagues in student affairs (see Figure 4). Conversely, a greater share of student affairs leaders rate increasing student enrollment and helping students to develop a sense of community as important to the services under their leadership than their colleagues in academic affairs.

Figure 3. How important are each of the following objectives to your college? Percent of chief academic and student affairs officers that rated each as extremely important.

Figure 4. How important are each of the following objectives to you for services under your leadership provided to students? Percent of chief academic and student affairs officers that rated each as extremely important.

The objectives of the college, as perceived by these leaders, are very much aligned with what they themselves hope to achieve within the services under their leadership. When comparing college and individual objectives, goals of increasing student retention, graduation, and course completion remain the three most important objectives. However, leaders within academic affairs align more closely with their colleges’ objectives than do those in student affairs. Student affairs leaders find that the goals related to addressing social and well-being needs are more important to the services under their leadership than to their college overall: 33 percent rate helping students develop a sense of community as extremely important to their college compared to 42 percent who rate this item as extremely important to their own leadership objectives. Additionally, only 14 percent of those in student affairs rate addressing social justice imperatives as extremely important to their college compared to 36 percent who rate this as extremely important to the services under their leadership.

Leaders in both academic and student affairs are united in their service to students and their success–seven in ten strongly agree that supporting student success is the most important priority at their college, and that their college has a well-developed strategy to meet changing student needs and practices. In the following sections, we explore current service provision at community colleges and anticipated future resource allocations more closely.

Service Provision & Organization

One of the fundamental research questions under investigation in this project relates to the provision and organization of services serving students at two-year colleges. When asked what services are provided at their college from a list of possible student support services, nearly all respondents indicated their college has financial aid, and over nine in ten reported their college offers orientation, academic advising, student computer labs, a library, tutoring center, student life/activities, dual enrollment services, IT/Helpdesk, and transfer services. On average, respondents indicated that their college offers 14 support services for the students at their college from a list of 17 potential services (see Appendix A).[17] Unsurprisingly, respondents from large colleges reported offering relatively more services than small or medium colleges.

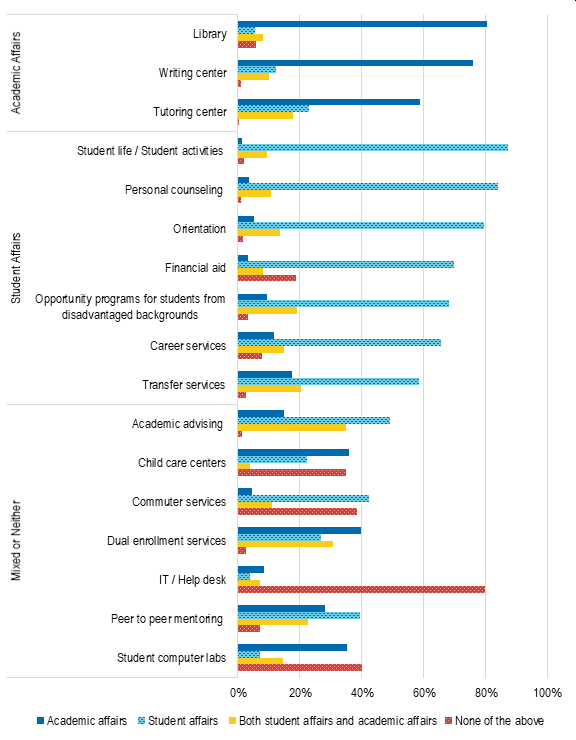

Senior administrators were asked whether the services offered at their college report to academic affairs, student affairs, both, or neither. The majority of respondents noted that the library, tutoring center, and writing center report to academic affairs and that student life/activities, personal counseling, orientation, financial aid, opportunity programs for students from disadvantaged backgrounds, career services, and transfer services report to student affairs (see Figure 5). Respondents frequently noted that some services—commuter services, child care, IT/help desks, and computer labs–do not report to either student or academic affairs.

Peer to peer mentoring services, academic advising and dual enrollment services tend to vary in reporting structure more so than other services listed, and in some cases report to both student and academic affairs. Forty percent of respondents said peer to peer mentoring reports to student affairs, while 30 percent listed it under academic affairs, and 20 percent said it reports to both. Roughly 49 percent of respondents said that academic advising reports to student affairs, compared to 35 percent who said that advising falls to both student and academic affairs. Similarly, about three in ten indicated dual enrollment services report to student affairs, four in ten to academic affairs, and three in ten to both student and academic affairs.[18]

Figure 5. To what area(s) of your college do the following services report? Percent of respondents that indicated whether each service provided at their college reports to student affairs, academic affairs, both, or neither.

When asked to rate the importance of various services offered at their college in supporting student success, 87 percent of respondents rated financial aid extremely important, followed by academic advising (76 percent), and the tutoring center (58 percent). About 37 percent of respondents said that the library is extremely important in contributing to student success. This is particularly noteworthy given that a majority of students frequently rated the library as a promising source of support for new services, compared to other locations on campus, as we uncovered in earlier research with students across seven partner community colleges.[19]

In some instances, senior administrators, particularly academic affairs leaders, tend to rate the services under their leadership as more important to supporting student success than those not under their leadership. A greater share of academic affairs leaders rate tutoring and writing centers, as well as child care centers, as extremely important compared to their colleagues in student affairs (see Figure 6). Likewise, a greater share of leaders in student affairs rate student life/activities as important to contributing to student success. Other services are rated similarly in importance across senior administrators.

Figure 6. Based on anything you know, have heard, or just happen to think, how important are each of the following services in supporting student success at your college? Percent of chief academic and student affairs officers that have this service currently offered at their college and rated each as extremely important.

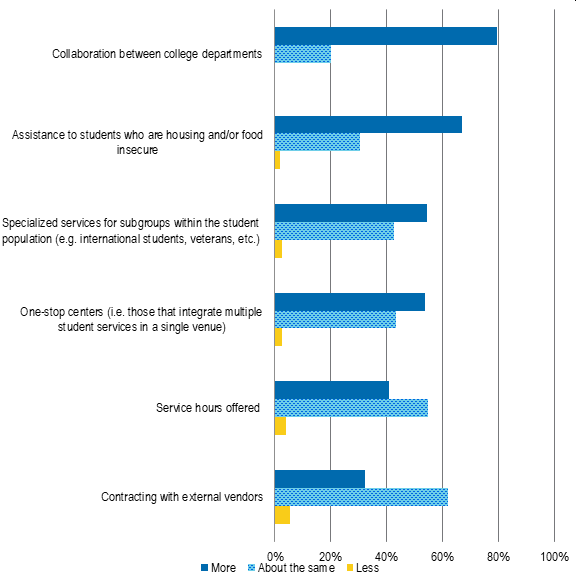

Five in ten respondents strongly agree that the services under their leadership collaborate closely with those not under their leadership to improve student success. This may be integral to service provision in the future, as eight in ten respondents anticipate seeing more collaboration between departments over the next five years (see Figure 7). Greater shares of leaders in student affairs and in combined student and academic affairs roles agree that their services collaborate closely with other units compared to respondents solely in academic affairs: about 55 percent of student affairs leaders and 54 percent of leaders in combined roles strongly agree compared to 41 percent of academic affairs leaders. About 42 percent of student affairs leaders and 54 percent of combined student and academic affairs leaders strongly agree that services under their leadership have clearly articulated how they contribute towards student success, compared to 35 percent of academic affairs leaders.

Additionally, about 92 percent of respondents from large colleges anticipate collaboration to increase compared to 82 percent of respondents from medium colleges and 68 percent from small ones. While limited resources may hinder these goals, collaboration between academic and student affairs may be an intuitive and beneficial way to use limited resources more effectively as demonstrated by past studies.[20]

In the next five years, about seven in ten senior administrators also anticipate providing more assistance to students who are housing and/or food insecure, 55 percent anticipate providing more specialized services for subgroups within the student population, and 54 percent anticipate more one-stop centers (see Figure 7). Over half of leaders in academic and student affairs anticipate that the service hours they offer students will stay the same. Similarly, over half of the respondents think contracting with external vendors will stay the same over the next five years

Figure 7. Do you anticipate seeing more, less, or about the same of each of the following in the services provided to students at your college over the next five years? Percent of respondents that anticipate seeing more, less, or about the same for each item.[21]

Decision Making

When making decisions about services for students, senior administrators typically consider the perspectives of various individuals and governing bodies to inform their choices. Student and faculty perspectives, along with the vision and strategy of senior administrative leadership themselves, are rated as the most influential in shaping student support services. About nine in ten respondents rate academic and student affairs leaders as highly influential for shaping services under their leadership, followed by students (88 percent), faculty (81 percent), and accreditors (75 percent). Around half indicated state government agencies and board members as highly influential, and about two in ten rate librarians or library staff as highly influential. Not only are specific people influential within the decision making process, but data collection and assessment as well as budgetary restrictions are at the forefront when making choices for service provision.

Data Collection & Analysis

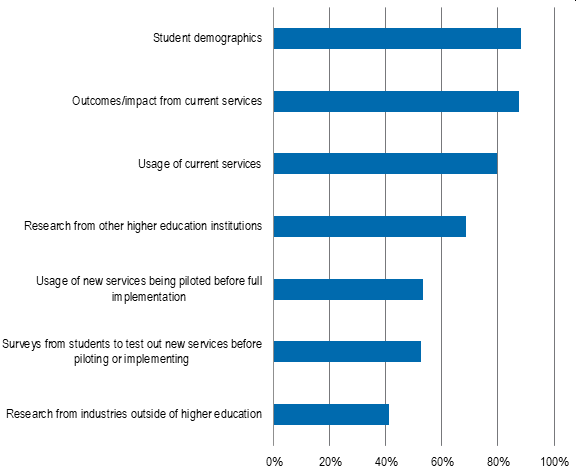

Senior administrators often use data in their decision-making processes: roughly 88 percent of respondents are currently collecting and/or analyzing data on student demographics, followed by outcomes and impact from current services (87 percent), and usage of current services (80 percent) to inform their vision and strategy (see Figure 8). About 87 percent of leaders in student affairs gather data to assess the use of current services compared to 78 percent of their academic affairs peers. Conversely, leaders in academic affairs are more likely to look to research both from other higher education institutions (73 percent) and from industries outside of the higher education sector (50 percent) than their colleagues in student affairs (64 percent and 35 percent respectively).

Figure 8. What data, if any, do you collect and/or analyze for decision-making related to the services under your leadership provided to students? Please select all that apply. If none of the following are collected or analyzed, please leave blank. Percent of respondents that selected each of the following items.

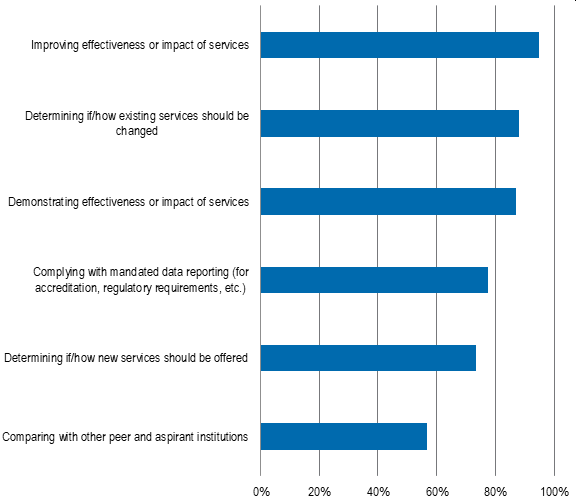

These data are primarily collected for improving the effectiveness or impact of services (95 percent), determining if/how existing services should be changed (88 percent), and demonstrating the effectiveness or impact of services (87 percent; see Figure 9). Comparing data with peer and aspirant institutions is a relatively lower priority to senior administrators—57 percent of respondents collect data for this purpose. Leaders in both student and academic affairs have similar reasoning for collecting and using the data for improving and demonstrating the value of their services, though 95 percent of leaders in student affairs use data to determine if/how to change existing services compared to 86 percent of those in academic affairs. From these responses, we can see that student affairs leaders typically look to internal data sources to improve service provision while those in academic affairs might be more prone to examine external data from other institutions or industries.

Figure 9. Why do you collect and/or analyze these data? Please select all that apply. Percent of respondents that selected each of the following items.

Funding

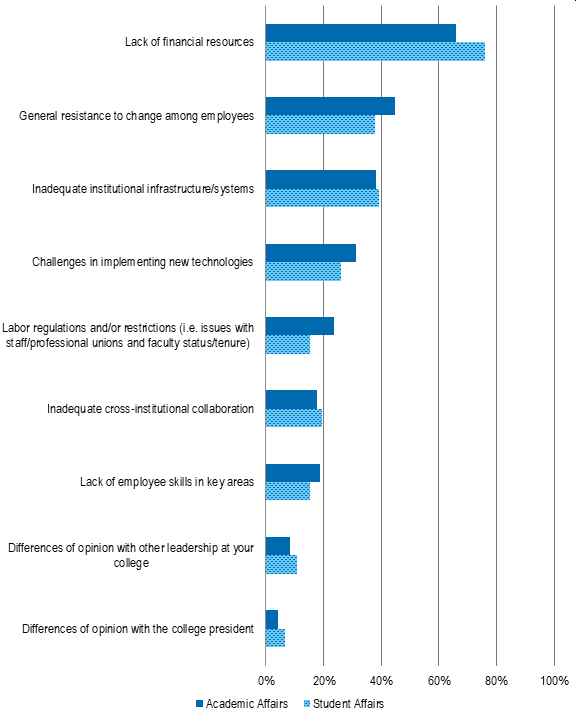

Limited financial resources impede senior administrators’ ability to make needed or desired changes at their college, according to seven in ten respondents. Other roadblocks include a general resistance to change among employees (41 percent) and inadequate institutional infrastructure or systems (40 percent; see Figure 10). Additionally, a little less than half of respondents agree that they lack the resources needed to contribute to student success effectively.

Figure 10. What are the primary constraints on your ability to make desired changes in your college? Please select up to three items below. Percent of respondents that selected each of the following items.

Although financial limitations are rated as a primary constraint across all respondents, 76 percent of student affairs leaders report financial restrictions compared to 66 percent of academic affairs leaders (see Figure 11). While greater shares of student affairs leaders cited limitations with financial resources, more academic affairs leaders indicated difficulties with general resistance to change among employees, implementing new technologies, and labor regulations and/or restrictions, perhaps because teaching faculty and the curriculum fall under their leadership in addition to support services. Additional examples of constraints mentioned by respondents in open-text responses included lack of time, understaffing, and decreased enrollment.

Figure 11. What are the primary constraints on your ability to make desired changes in your college? Please select up to three items below. Percent of chief academic and student affairs officers that selected each of the following items.

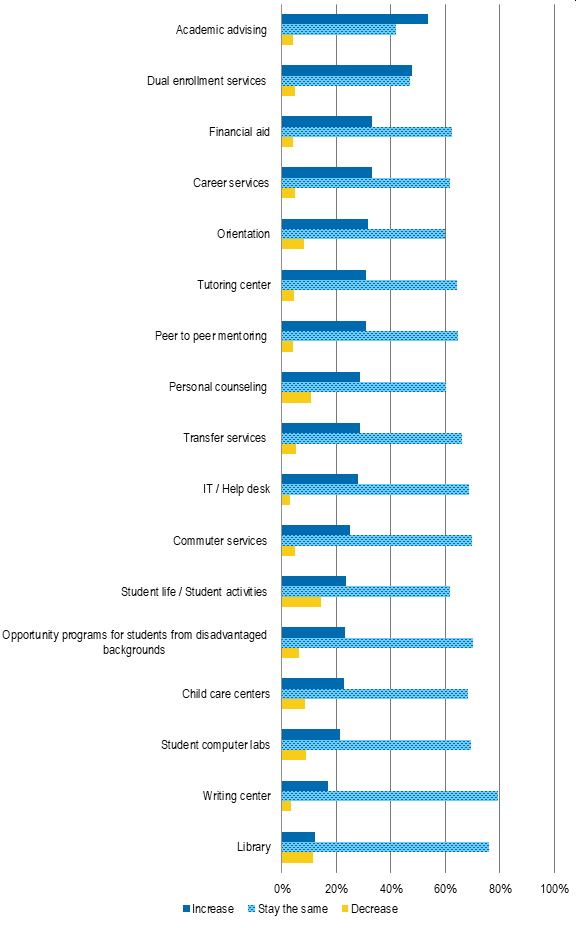

Respondents anticipate budgets for most services at their college will stay the same over the next five years (see Figure 12). Less than 20 percent of respondents believe that any of the services’ budgets will decrease over time, while about half of respondents anticipate academic advising and dual enrollment budgets will increase. About 20 percent of senior administrators anticipate the budgets of student computer labs and the writing center to increase over the next five years, whereas only 12 percent of respondents anticipate the library’s budget to increase, and 76 percent anticipate the library’s budget will stay the same.

Figure 12. Do you anticipate the budget for each of these services provided to students at your college to increase, decrease, or stay the same over the next five years? Percent of respondents that have budgetary responsibility for each of the following services, and that indicated the budget would increase, decrease, or stay the same for each.

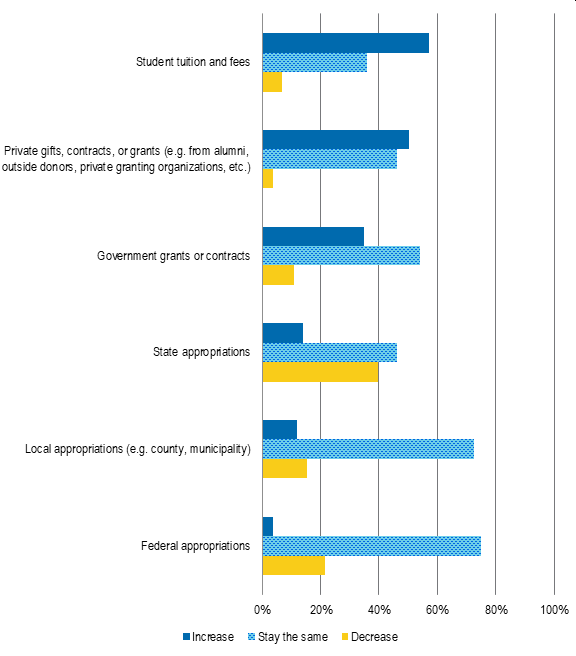

Many sources for funding are expected to remain the same over the next five years (see Figure 13). However, a greater share of senior administrators anticipate funding from non-governmental sources will either increase or stay the same over the next five years, whereas they think state and federal appropriations will stay the same or decrease over time. About 57 percent of senior administrators anticipate that student tuition and fees will increase as a source of funding over the next five years, followed by private gifts, contracts, or grants (50 percent), and government grants or contracts (35 percent). Three quarters of academic and student affairs leaders expect federal appropriations to stay the same, and four in ten anticipate state appropriations to decrease.[22]

Figure 13. Do you anticipate each of the following funding sources at your college to increase, decrease, or stay the same over the next five years? Percent of respondents that indicated each will increase, decrease, or stay the same.

Lastly, to determine where senior administrators would like to prioritize greater investment, we asked respondents what they would do, hypothetically, if given a 10 percent increase to the budget they already receive. Six in ten senior administrators would allocate this extra money towards new employees and/or refined positions, followed by technology and/or systems (49 percent), new service area development (32 percent), and employee salary/compensation increases (31 percent). Academic affairs leaders would be more likely to use this budget increase for technology and/or systems (53 percent) and new facility expansions and/or renovations (27 percent) compared to their colleagues in student affairs (45 percent and 18 percent respectively). Thirty-four percent of student affairs leaders would use the additional funding for marketing toward prospective students compared to 16 percent of academic affairs leaders.

Staffing

Staffing also presents unique difficulties for senior administrators, as about four in ten designated general resistance to change among their employees as a primary constraint to making desired changes and, as previously noted, a general lack of funds can certainly present issues with understaffing (see Figure 10).

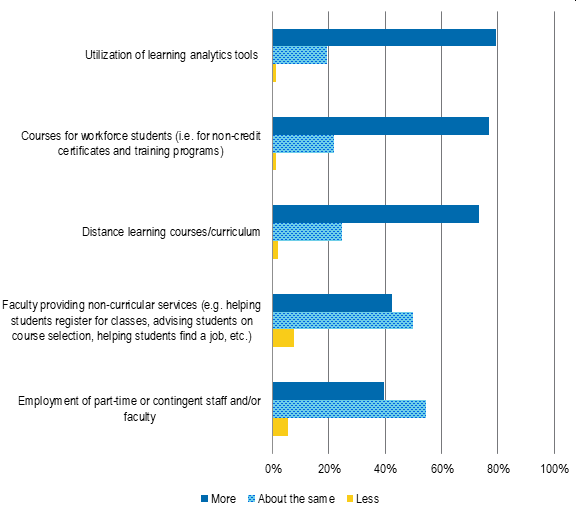

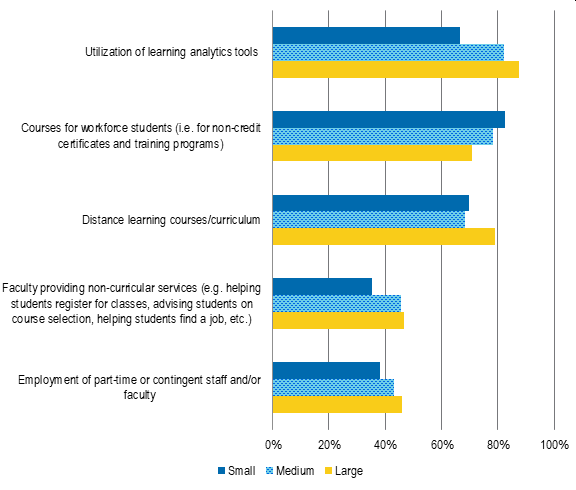

Although resistance to change is viewed as a primary constraint to making changes, many senior administrators expect the roles of their current college employees to expand to more non-curricular responsibilities (see Figure 14). About four in ten expect the provision of these non-curricular services (i.e. helping students register for classes, advising students on course selection, etc.) to increase over the next five years, and five in ten expect this to stay about the same. Additionally, senior administrators anticipate that faculty will need to administer new elements in their curriculum. About eight in ten expect the use of learning analytics tools to increase over the next five years, 77 percent expect courses for workforce students to increase, and 73 percent anticipate more distance learning courses in the curriculum. Four in ten respondents expect the employment of contingent and part-time faculty and staff to increase over the next five years and 55 percent expect the level of employment of these roles to stay the same.[23]

Figure 14. Do you anticipate seeing more, less, or about the same of each of the following in the services provided to students at your college over the next five years? Percent of respondents that they anticipate seeing more, less, or about the same for each item.

Respondents from large colleges anticipate an increase of learning analytics tools and distance learning courses, while smaller colleges anticipate that they will add more courses for workforce students over the next five years (see Figure 15). Large and medium sized colleges also anticipate the provision of non-curricular services to increase in the coming years. Additionally, about 46 percent of respondents from vocational-focused colleges anticipate increased employment of part-time or contingent staff and/or faculty compared to about 38 percent of respondents from transfer-focused and mixed-focused colleges. About 77 percent of respondents from both transfer-focused and mixed-focused colleges anticipate increased distance learning courses compared to 64 percent of respondents from vocational-focused colleges.

Figure 15. Do you anticipate seeing more, less, or about the same of each of the following in the services provided to students at your college over the next five years? Percent of respondents that they anticipate seeing more of each item by size of institution.

Respondents noted several staffing challenges, including rewarding high-performing employees (75 percent), building a pool of qualified candidates for open positions and providing competitive compensation packages to prospective employees (65 percent), and filling vacant positions in a timely manner (64 percent). Senior administrators in student and academic affairs experience similar difficulty with rewarding high-performing employees, though academic affairs leaders have a greater difficulty building a pool of qualified candidates (72 percent rated as difficult) and developing the knowledge, skills, and abilities of employees (52 percent) compared to student affairs leaders (58 percent and 35 percent respectively). Student affairs leaders reported encountering greater challenges with retaining employees and reducing turnover (37 percent) than did their colleagues in academic affairs (26 percent).

Role of the Library

As one of the main goals of this multi-year research initiative is to determine what types of library services community colleges can offer to students in conjunction or coordination with other academic and student services, we asked chief academic and student affairs officers about their perceptions of the role of the library. We also plan on asking many of these questions to library directors in a later phase of this project.

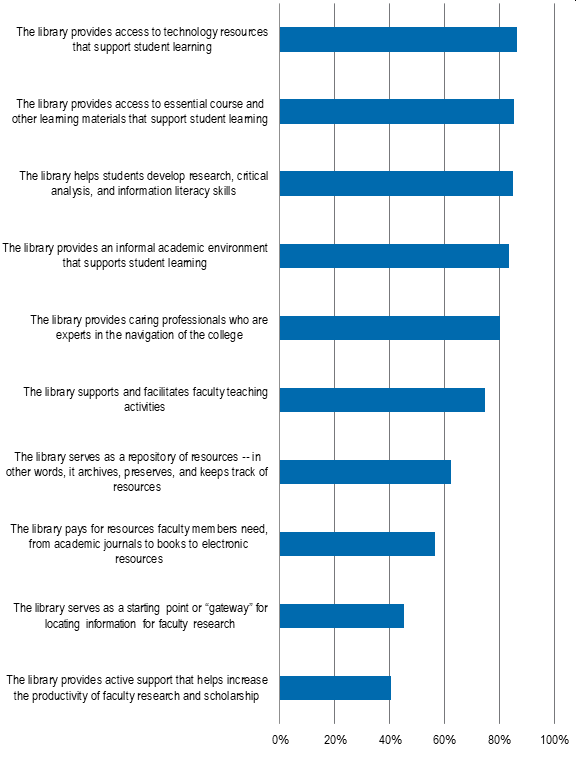

Academic and student affairs leaders tend to view library roles that are access- and student learning-oriented as more important to student success than perhaps more traditional or scholarly roles of the library, such as the buyer of needed resources and a gateway for locating new information.[24] In their valuation, the library’s most important roles are providing access to technology that supports student learning, providing essential course and other learning materials, helping students develop research, critical analysis, and information literacy skills, and providing an informal academic environment that supports student learning (see Figure 16).

Figure 16. How important is it to you that your college library provides each of the functions below or serves in the capacity listed below? Percent of respondents that rated each as highly important.

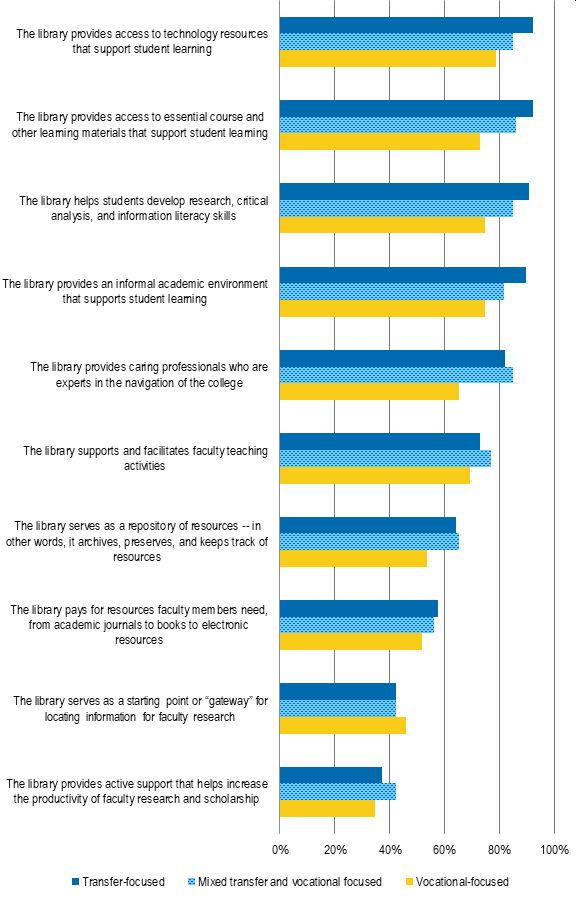

Greater shares of respondents from transfer-focused and mixed-focused colleges rate most aspects of the library as extremely valuable compared to respondents from vocational-focused colleges (see Figure 17). However, respondents from vocational-focused colleges rate the library as a gateway for locating information for faculty research as slightly more important than respondents at transfer- and mixed-focused colleges.

Additionally, respondents from small and medium colleges rate the value of teaching-related support of their library more highly than respondents from large colleges: about 77 percent of respondents from medium colleges and 74 percent from small colleges rated the library’s support and facilitation of teaching activities as extremely important compared to 66 percent of respondents from large colleges. About 62 percent of respondents from small colleges also find the library’s role as a buyer of needed resources, such as academic journals to books and electronic materials, to be extremely important compared to 57 percent of respondents from medium colleges and 51 percent from large colleges. Almost nine in ten respondents from large and medium sized colleges rate the library’s support in developing students’ research, critical analysis, and information literacy skills as extremely important compared to eight in ten respondents from small colleges.

Figure 17. How important is it to you that your college library provides each of the functions below or serves in the capacity listed below? Percent of chief academic and student affairs officers that rated each as highly important, by undergraduate instructional program.

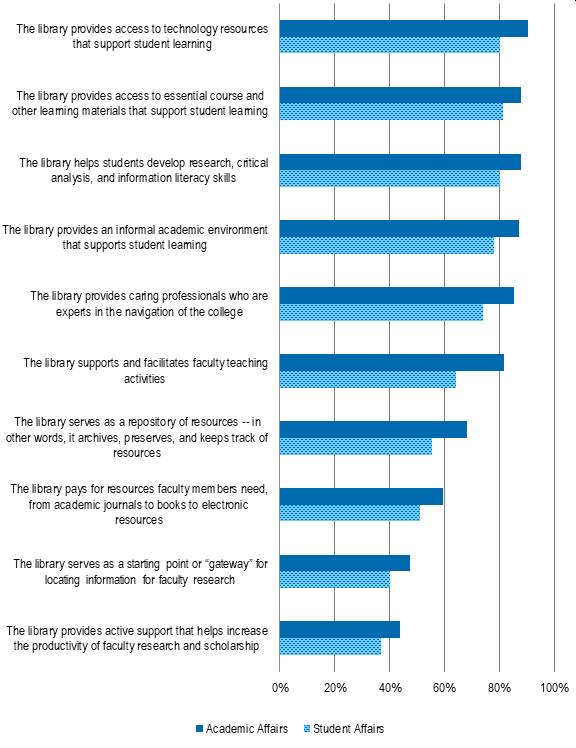

Leaders in academic affairs rate each role of the library as more important than their colleagues in student affairs.[25] In particular, the library’s role in supporting teaching activities, as an archive of resources, and in the provision of caring professionals who are experts in navigating college are rated as substantially more important by academic affairs leaders (percentage point differences of about 18 points, 11 points, and 9 points respectively) (see Figure 18).

Figure 18. How important is it to you that your college library provides each of the functions below or serves in the capacity listed below? Percent of chief academic and student affairs officers that rated each as highly important.

Concluding Remarks

Students can face substantial difficulty in navigating college resources and services that may have the potential to help them reach the goals they seek to achieve. Through this project, we have now documented the landscape of service offerings across student and academic affairs at two-year, not-for-profit colleges. While many services are provided across the majority of colleges, some are offered much less frequently, including peer to peer mentoring, child care, and commuter services. Mapping the provision of these services across colleges is an important first step in providing higher education leaders with an evidence base for making decisions about services to continue or add in the future.

Mapping the provision of these services across colleges is an important first step in providing higher education leaders with an evidence base for making decisions about services to continue or add in the future.

Senior administrators are especially focused on increasing student retention, graduation, and course completion, and face financial and staffing barriers in doing so. They use a variety of data to make decisions in planning for future service provision and evaluating the effectiveness of their current services. And, while they highly value student-centered roles of the library, faculty- and research-facing roles are considered to be of relatively lesser importance.

We have also established commonalities and areas of convergence regarding the configuration of these services across student and academic affairs. Reporting lines are clear for many of these services, though many have shared responsibilities across functional areas. Many chief academic and student affairs officers anticipate increased collaboration in the coming years.

The information presented in this report begins to paint a picture of current service provision, the strategy driving it, and the factors that constrain it. We can begin to imagine new models for learning and collaboration across and within institutions, and anticipate what is on the horizon for future offerings. These results also shed light on the role that the library plays in supporting student needs.

In our next phases of work, we will be conducting site visits in 2020 with a diverse set of colleges to explore in more depth how these services are structured and the extent to which they are currently meeting student needs. In early 2021, we will turn to surveying community college library directors on their own strategies, resources, and constraints alongside other institutional support providers. We will conclude the project with an invitational workshop to bring together key leaders and participants from these research engagements to discuss action agendas for libraries and other service providers.

Through this project, we aim to help colleges institutionalize findings and organize themselves to better support student needs by enabling leaders to strengthen and reconfigure services to increase positive student outcomes. We look forward to sharing our work and engaging thoughtfully with the higher education community as it continues.

Appendix A: List of Student Support Services

| Student support service | Number of respondents with this service at their college | Percentage of respondents with this service at their college[26] |

|---|---|---|

| Academic advising (i.e. professional staff assisting with major and course selection, developing plan of study, etc.) | 244 | 98% |

| Career services | 217 | 88% |

| Child care centers | 103 | 42% |

| Commuter services (i.e. any assistance with transportation to campus(es), parking, etc.) | 127 | 52% |

| Dual enrollment services (i.e. admitting/enrolling high school students to earn college credits) | 237 | 96% |

| Financial aid | 246 | 100% |

| IT/Help desk | 233 | 94% |

| Library | 237 | 98% |

| Opportunity programs for students from disadvantaged backgrounds (i.e. EOP programs, TRIO programs, etc.) | 180 | 73% |

| Orientation | 244 | 99% |

| Peer to peer mentoring (i.e. new students paired with more experienced students) | 115 | 47% |

| Personal counseling (i.e. professional staff assisting with treatment, outreach, and/or educational programs for the psychological well-being of students) | 190 | 77% |

| Student computer labs | 243 | 98% |

| Student life/ Student activities (i.e. student clubs/organizations, recreational activities, etc.) | 241 | 97% |

| Transfer services (i.e. assistance to students transferring to/from the college) | 227 | 92% |

| Tutoring center | 240 | 98% |

| Writing center | 196 | 81% |

Endnotes

- For more information on the CCLASSS project, see Melissa Blankstein, Christine, Wolff-Eisenberg, and Braddlee, “Student Needs Are Academic Needs: Community College Libraries and Academic Support for Student Success, “Ithaka S+R, 30 September 2019, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.311913, and Christine Wolff-Eisenberg and Braddlee, “Amplifying Student Voices: The Community College Libraries and Academic Support for Student Success Project,” Ithaka S+R, 13 August 2018, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.308086. ↑

- The list of colleges included within the sample was determined by Carnegie Classification and pulled from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System based on data from the 2017 academic year. The following Carnegie Classifications are those that make up our sample: Associate’s Colleges: High Transfer-High Traditional; Associate’s Colleges: High Transfer-Mixed Traditional/Nontraditional; Associate’s Colleges: High Transfer-High Nontraditional; Associate’s Colleges: Mixed Transfer/Career & Technical-High Traditional; Associate’s Colleges: Mixed Transfer/Career & Technical-Mixed Traditional/Nontraditional; Associate’s Colleges: Mixed Transfer/Career & Technical-High Nontraditional; Associate’s Colleges: High Career & Technical-High Traditional; Associate’s Colleges: High Career & Technical-Mixed Traditional/Nontraditional; Associate’s Colleges: High Career & Technical-High Nontraditional; Special Focus Two-Year: Health Professions; Special Focus Two-Year: Technical Professions; Special Focus Two-Year: Arts & Design; Special Focus Two-Year: Other Fields; and Baccalaureate/Associate’s Colleges: Associate’s Dominant. ↑

- The following professional associations aided in the promotion of the survey to their constituents: Arkansas Community Colleges; Colorado Community College System; Technical College System of Georgia; Idaho State Board of Education; Iowa Association of Community College Trustees; Kentucky Community and Technical College System; Massachusetts Association of Community Colleges; Maryland Association of Community Colleges; Pennsylvania Commission of Community Colleges; Texas Association of Community Colleges; and Virginia Community College System. ↑

- Margin of error is 5 percent for n = 264 at the 90 percent confidence interval. ↑

- There was a response rate of about 6 percent from for-profit colleges, compared to a response rate of about 11 percent from private, not-for-profit colleges, and about 13 percent from public colleges. ↑

- We intend to deposit the underlying dataset as part of the Ithaka S+R Surveys of Higher Education Series with ICPSR (https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/series/226) for long-term preservation and access. Please contact research@ithaka.org if we can provide any assistance in accessing and working with the dataset. ↑

- Data were taken from IPEDS and are reported by the individual college to IPEDS on an annual basis; these data were a part of the fall 2017 reporting period. ↑

- As defined by IPEDS, “primarily nonresidential” includes colleges with fewer than 25 percent of degree-seeking students that live on campus and/or fewer than 50 percent who attend full time. This subgroup within the sample is comprised of respondents within the small, medium, and large, 4-year, primarily nonresidential Carnegie classifications for size and setting and were excluded from stratified analysis due to their low number of respondents compared to other subgroups. ↑

- Respondents from colleges within the Baccalaureate/associates colleges, Special focus: two-year institutions, and No graduate coexistence classifications were excluded from stratified analysis due to their low number of respondents compared to other subgroups. ↑

- Referred to as transfer-focused throughout this report. ↑

- Referred to as mixed transfer and vocational-focused, or mixed-focus, throughout this report ↑

- Referred to as vocational-focused throughout this report. ↑

- Comprised of respondents within the Arts & sciences, Arts & sciences plus professions, Balanced arts & sciences/professions, Professions plus arts & sciences, and Professions focused, no graduate coexistence Carnegie classifications for undergraduate instructional program. ↑

- Christine Wolff-Eisenberg and Braddlee, “Amplifying Student Voices: The Community College Libraries and Academic Support for Student Success Project,” Ithaka S+R, 13 August 2018, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.308086. ↑

- Melissa Blankstein, Christine, Wolff-Eisenberg, and Braddlee, “Student Needs Are Academic Needs: Community College Libraries and Academic Support for Student Success, “Ithaka S+R, 30 September 2019, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.311913. ↑

- Respondents were presented with the following two questions: (1) How important are each of the following objectives to your college? and (2) How important are each of the following objectives to you for services under your leadership provided to students? ↑

- This list is not exhaustive of every type of support service that can be offered to students, as there are many specialized and unique services that colleges can and do offer to students beyond what is contained within this list. The list was generated based on services that have been found to be the most common services offered across colleges, as well as support services students highlighted during interviews within the previous CCLASSS initiative. ↑

- A possible explanation for why dual enrollment programs vary by college and by state could be that certain states allow the discretion of local districts to make decisions as to whom has the budgetary responsibility of this service. The organization of dual enrollment programs may also be distributed across departments, with academic affairs managing curriculum-based programming and student affairs managing enrollment to the program. For more information, see: http://ecs.force.com/mbdata/MBQuest2RTanw?Rep=DE1904;John Mark Grubb, Pamela H. Scott, & Donald W. Good, “The Answer is Yes: Dual Enrollment Benefits Students at the Community College,” Community College Review 45, no.2 (2017): 79-98, DOI: 10.1177/0091552116682590; and,Dennis Pierce, “The Rise of Dual Enrollment,” Community College Journal April/May (2017): 16-25, https://www.mtsac.edu/president/cabinet-notes/2016-17/ccjournal_Rise_of_Dual_Enrollment_Apr-May_2017.pdf. ↑

- Melissa Blankstein, Christine, Wolff-Eisenberg, and Braddlee, “Student Needs Are Academic Needs: Community College Libraries and Academic Support for Student Success, “Ithaka S+R, 30 September 2019, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.311913. ↑

- Recent survey results highlight the cost-effective elements of collaboration between the library (a service typically offered by academic affairs) and other non-academic departments as seen in Amy Wainwright and Chris Davidson, “Academic Libraries and Non-Academic Departments: A Survey and Case Studies on Liaising Outside the Box,” Collaborative Librarianship, 9, no. 2, (2017): 117-134, https://digitalcommons.du.edu/collaborativelibrarianship/vol9/iss2/9/.Also, a study on a newly implemented plan for collaboration between academic and student affairs at Kingsborough Community College demonstrated the positive effects a partnership can have on students, as seen in Peter Cohen, David Gomez, Regina Peruggi, Marissa R. Schesinger, and Stuart Suss, “Partnering with Academic Affairs in the Community College Setting,” in Handbook for Student Affairs in Community Colleges, Ashley Tull, Linda Kuk, and Paulette Dalpes (Virginia: Stylus Publishing, 2015), 85-97. ↑

- This figure represents a subset of all items from the question answered by respondents. For the rest of the items listed in this question, see Figure 14. ↑

- For more information on how governmental and non-governmental funding sources have shifted over time, see: https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=76; Michael Mitchell, Michael Leachman, and Kathleen Masterson, “Funding Down, Tuition Up: State Cuts to Higher Education Threaten Quality and Affordability at Public Colleges,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, (2016), 1-28, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/5-19-16sfp.pdf. ↑

- In 2014, contingent or part-time faculty taught over half of courses at two-year colleges. For more information on increasing adjunctification and contingent labor in higher education, see Center for Community College Student Engagement, Contingent Commitments: Bringing Part-time Faculty into Focus (A special report from the Center for Community College Student Engagement), Austin, TX: The University of Texas at Austin, Program in Higher Education Leadership, 2014; and Susan Bickerstaff and Octaviano Chavarín, “Understanding the Needs of Part-Time Faculty at Six Community Colleges,” Community College Research Center, November 2018, https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/understanding-part-time-faculty-community-colleges.html. ↑

- Ithaka S+R has been reporting data on these library roles over time through our US Faculty and Library Director Surveys at four-year institutions. You can find the most recent findings from these surveys here: Melissa Blankstein and Christine Wolff-Eisenberg, “Ithaka S+R US Faculty Survey 2018,” Ithaka S+R, April 12, 2019, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.311199; and Christine Wolff-Eisenberg, “US Library Survey 2016,” Ithaka S+R, April 3, 2017, https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.303066. ↑

- Overall, about 38 percent of leaders in academic and student affairs similarly view the library as extremely important to supporting student success (see Figure 6). ↑

- Percentages rounded to the nearest whole number. ↑

Attribution/NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of the license, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.