Leading the Library by Looking Beyond the Library

Library directors face a number of leadership dilemmas. Rising from the ranks, many feel the pull—or the need, given resource constraints—to work shoulder-to-shoulder with front-line employees as a “member of the team.” At the same time, many feel the need to engage with non-library constituencies across the campus and beyond in ways that take them out of the library. Which of these leadership models best positions the library for success?

Last month, we released findings from our national survey of library deans and directors at four-year colleges and universities across the United States. While much has changed in the higher education sector, let alone the world, since survey data were collected in fall 2019, the 662 responses collected provide us with the best picture of library leader strategies and intentions prior to the global pandemic.

One of our key findings is that library directors perceive the value of their roles—and the roles of their libraries—to be declining in the eyes of their supervisors and other higher education leaders. Continuing a trend found in our 2016 survey, directors at all institution types feel less valued by, involved with, and aligned strategically with their supervisors and other senior academic leadership. And, while library directors’ own perceptions of the value of various functions of the library have remained high, they don’t believe their supervisors value these functions as highly. Thus, the gap between library directors and their supervisors has only grown wider.

Following the release of both the 2016 and subsequent 2019 survey findings, readers have asked why this disconnect might be growing. This prompted us to investigate: What does library strategy look like when library directors feel aligned with their direct supervisors, view themselves as part of senior academic leadership, and see their budget as signaling the importance of the library? Conversely, what does strategy look like when these conditions are not met?

To answer these questions, we first created a scale averaging responses across three key items related to director and library value:

- “My college or university’s budget allocations to the library in recent years have demonstrated that it recognizes the value of the library.”

- “I am considered by academic deans and other senior administrators to be a member of my institution’s senior academic leadership.”

- “My direct supervisor and I share the same vision for the library.”[1]

This produced what we refer to in this post as the “director/library value scale.” The highest value on this scale is 10 (if a respondent provided the most positive response to every statement) and the lowest is a 1 (if the most negative responses for all were provided). We then ran simple correlations with the items in the survey related to strategy and vision that we hypothesized would be related to director and library value.

A median split of the “director/library value scale” was created to categorize responses. Those that fell below the median were categorized as “low value” and those that were equal to or above the median were considered “high value.” All other variables were categorized as they were in the main report; for survey items with percentage responses, we used averages, and for those with Likert scales, we used the high end of the scales.[2] Only those results that are statistically significant have been included in our reporting.

What did we find? There is a consistent relationship between the library’s investment in initiatives that align with broader institutional missions beyond the library and how directors believe both they and their libraries are valued. As directors prepare to enter a new academic and fiscal year likely shaped substantially by budget constraints and uncertainty, difficult decisions about how to continue to invest time and resources will likely abound.

How directors spend their time

Directors who perceive their role and their library to be relatively more valued tend to spend more of their time engaging in institution-wide initiatives and campus engagement outside of the library. They are less likely to spend time on direct service provision than directors who perceive their role and the library to be less valued.

The data suggest that, on average, directors who spend more time on activities that allow them to engage with other senior leadership, such as through institution-wide initiatives, possess stronger relationships with other senior leaders and perhaps therefore have more opportunities to demonstrate the value of the library. On the other hand, those who spend more time directly providing services for library users have fewer of these opportunities. Of course, the relationship here is correlational, not causal, so the effect may go in either direction—that is, higher perceived value may be a result of the way time is spent, or the way that time is spent may be a result of higher perceived value.

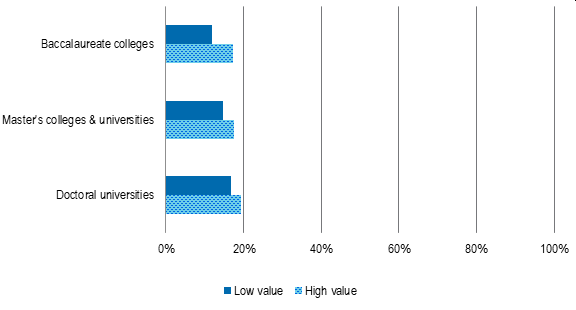

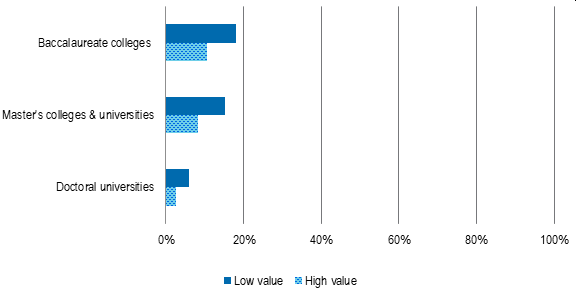

While there are differences in the average time spent on both of these activities by Carnegie Classification, the patterns between time spent and perceived value are consistent across institution type. See Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1. In your current role, what percentage of your time do you spend on institution wide-initiatives / campus engagement outside of the library with the college/university? Average time spent by perceived value (low versus high) and Carnegie Classification.

Figure 2. In your current role, what percentage of your time do you spend on direct service provision (e.g. answering reference questions) / library programming? Average time spent by perceived value (low versus high) and Carnegie Classification.

How directors prioritize library initiatives

We also asked directors in the survey about how they think their direct supervisors value seven core functions of the library. Intuitively, a greater share of directors who feel relatively more valued also are more likely to believe that their direct supervisor considers each function to be “highly important.”

At baccalaureate colleges, directors perceive that both they and their library are more highly valued when they also perceive that their supervisors highly value their teaching functions. This includes the library supporting and facilitating faculty teaching activities as well as helping undergraduates develop research, analysis, and information literacy skills. For baccalaureate college directors, those who feel more valued are also themselves prioritizing functions associated primarily with student learning, including provision of physical space and the development of research skills.[3] Perceived director and library value is highest when priorities are aligned with the institutional focus on teaching and learning.

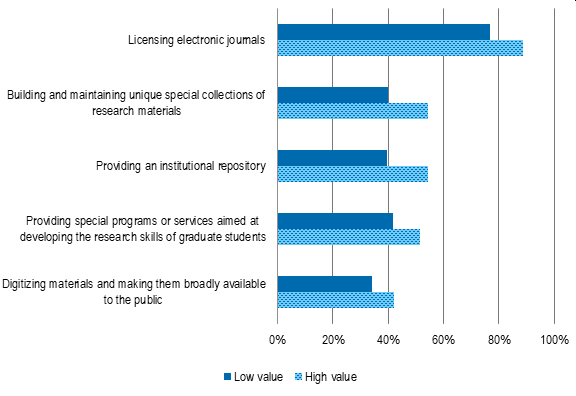

Conversely, at doctoral universities, directors perceive that both they and their library are more highly valued when they also perceive that their supervisors highly value their research functions. This includes the library serving as a repository of resources and providing active support to increase the productivity of faculty research and scholarship. Respondents who feel more valued also tend to prioritize functions related to collections and archiving, digital operations, and teaching and learning functions that are research-focused. Doctoral university respondents are prioritizing many of these areas to a greater degree than directors from other institution types, but the differences are even more pronounced for those that perceive themselves and their library to be highly valued. See Figure 3.

Figure 3. How much of a priority is each of the following functions in your library? Percentage of doctoral university respondents that rated each function as a high or very high priority by perceived value (low versus high).

At master’s institutions, a greater share of directors who feel more highly valued prioritize a mix of functions. These include collections and archiving, publishing, and teaching and learning.

Across these results, we see that library directors who have more opportunities to engage with other senior academic leadership and the institution as a whole report more positive perceptions of the director role and the library compared to those who have fewer of these opportunities. This is demonstrated both in the way that directors spend their time and in the initiatives that they prioritize. When there is greater emphasis on institution-wide initiatives and mission-focused priorities, there also tends to be greater valuation of the library and the individual leading it.

The authors thank Lisa Janicke Hinchliffe for asking a series of questions that served as the basis for this analysis.

- The reliability of these items was acceptable, cronbach’s α = .70. This suggests that participants responded relatively similarly to each of the three items on director and library value. ↑

- For more information on how variables were categorized, please see the “Data Analysis and Reporting” section of the main report: https://sr.ithaka.org/publications/ithaka-sr-us-library-survey-2019/. ↑

- These data were collected from October – December 2019 before the COVID-19 pandemic when nearly all libraries closed their physical locations. ↑