Prospective Student Veterans Face Complex Choices on the Journey to a Bachelor’s Degree

As Veteran’s Day approaches, there is renewed attention paid to those individuals who have served in our nation’s military and to the ways our nation repays that service. The majority of military service members often cite education benefits as one of their primary motivations for joining the military. However, once they leave the service, many veterans are not making best use of those benefits due to undermatching, whereby students attend institutions where they are far less likely to graduate. While institutional data on veteran graduation rates are almost non-existent, veterans are over-represented at institutions where all students are far less likely to graduate, a likely factor impacting degree attainment.

Ithaka S+R, as well as many colleges and universities, veteran service organizations, funders, researchers, and other key stakeholders, has spent years studying and troubleshooting undermatching (see here as one example of Ithaka S+R’s work). While we and our colleagues have recently made some progress on the issue, a constellation of structural barriers, at once social, economic, and psychological, are repeatedly cited as causes of undermatching. At high-graduation-rate institutions, veterans are simply missing from the applicant pool, although many more qualified veterans could apply.

There are numerous reasons that veterans undermatch at high-graduation-rate institutions, including a lack of quality information about their options and structural barriers in application, enrollment, and transfer processes. As one example, the 2023 “Best for Vets” list from Military Times, a list with significant penetration on bases and among would-be veteran postsecondary students, comprises schools with an average six-year graduation rate of only 58 percent (with some schools on the list reporting graduation rates as low as 16 percent, according to College Scorecard). And many high-graduation-rate institutions have application and transfer processes that do not account for the specific needs of student veterans, many who first enroll at a community college. These challenges ramify across the transition from service to and through school, making clear just how many different inflection points there are on a student veteran’s educational odyssey, and how easily one might be discouraged, or waylaid, on the path to a bachelor’s degree.

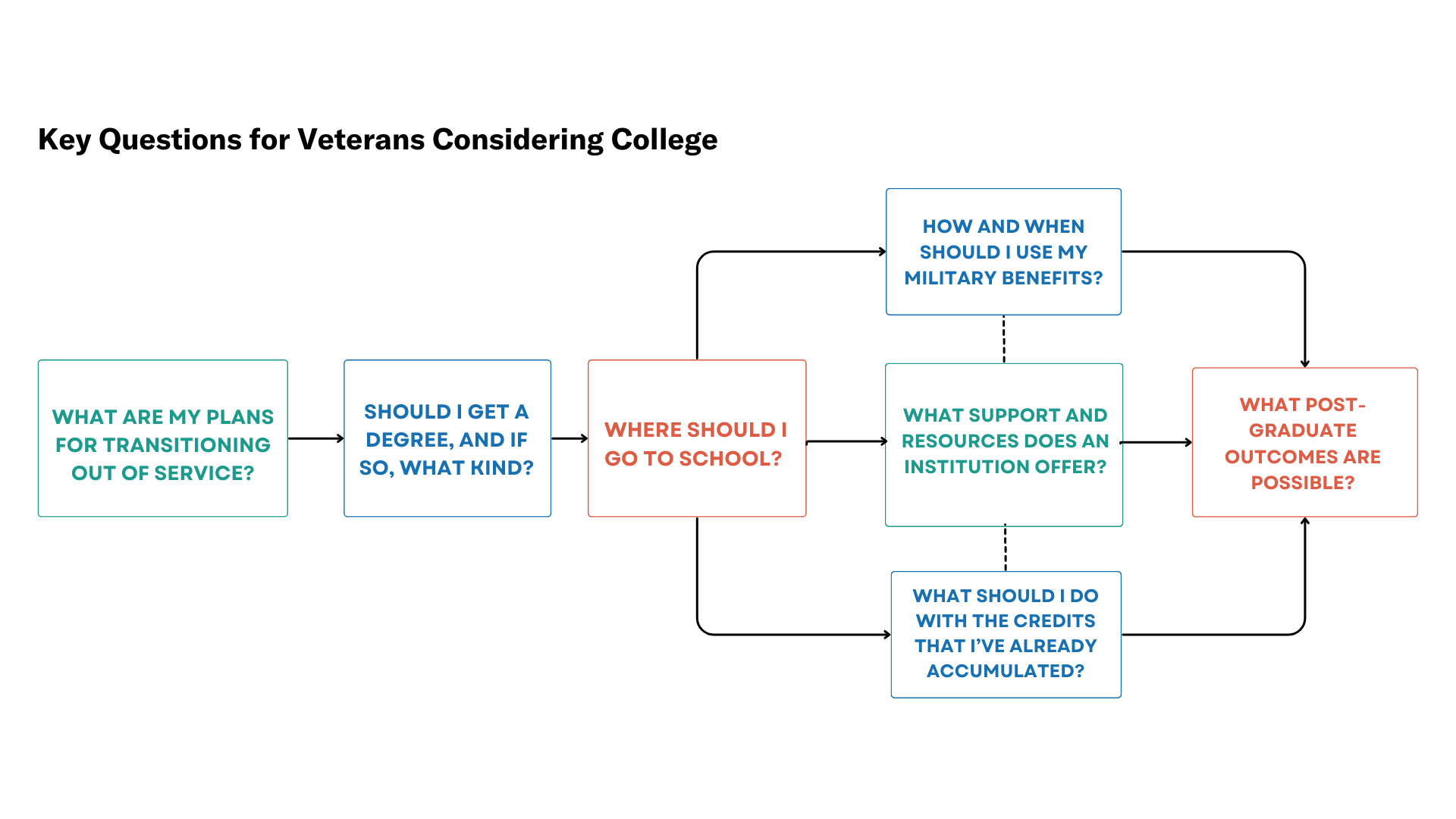

College administrators and higher education leaders would benefit from adopting the perspective of the student veterans to understand how undermatching happens in practice. To that end, in this blog, we undertook a thought experiment in journey mapping, an effort to trace the decisions active duty service members must make in pursuit of a bachelor’s degree. In what follows, we identify a sequence of questions that any prospective veteran student is likely to ask themselves as they navigate that postsecondary process (the journey map). We also provide context for each hypothetical by framing the individual motivations and larger structural forces shaping these questions. A visualization of this decision-making process is provided at the end of the document.

What are my plans for transitioning out of active service?

The military is widely known for the intensity and efficacy of its onboarding practices, with the ubiquity of ‘boot camps’ for all kinds of activities—from fitness to coding—highlighting how effectively these experiences can prepare participants for future success. Unfortunately, the transition out of the military is far less consistent, effective, or successful, with almost half of post-9/11 veterans reporting difficulty in the transition. These challenges persist, despite renewed efforts and resources invested in transition support activities, such as the Transition Assistance Program (TAP).

The investment in the transition process and the persistent challenges faced by transitioning veterans have inspired many attempts to better understand and improve the experience. An essential component of the many frameworks suggested is the pursuit of education post-service, either on its own or as part of a larger “well-being” construct. Including education in contemporary models to understand the military to civilian transition experience seems inevitable when the majority of service members cite educational benefits as a primary motivation for enlisting.

The priority that education receives in the recruitment process is, unfortunately, not matched in the military to civilian transition process. The majority of service members begin the transition process less than a year before the end of their service, leaving them with abbreviated opportunities to reflect on their options or to seek the information and resources about the significant post-separation life decisions they will imminently need to make. In the context of such a radical change in lifestyle, transitioning service members need proactive support and advising, including as to whether or not pursuing higher education makes sense as a next, or future step for them.

Should I get a bachelor’s degree, and if so, where?

While the benefits to a bachelor’s degree are well-documented, they may not always be clear to the military-affiliated population. Many veterans build skills in the military that, on the surface, may seem more aligned with alternative pathways to a career, like vocational training, trade school, and professional certificate programs.

Deciding to work toward a bachelor’s degree is a key step, but choosing to do so at an institution where the student is likely to graduate is also crucial. There are roughly 350 colleges and universities in the United States with six-year graduation rates above 70 percent. At other institutions, at least one in three students who enroll do not complete a bachelor’s degree within six years, or more likely, ever. For students from underrepresented backgrounds the rate of completion is even lower.

These high-graduation-rate schools include state flagships and elite private institutions, which may have a leg up in name recognition for the veteran community, but also include many small liberal arts colleges that can provide a well-supported path to a bachelor’s degree. These schools often excel at equipping students with skills needed in today’s labor market (critical thinking, communication, etc.), and the economic value-add of a liberal arts degree is particularly salient for low-income students, which many veterans are. Hopefully, as more research is done to understand the relationship between exposure to a liberal education and economic returns to students, these schools and their degree programs will receive more attention in the veterans community.

Who wants to enroll a student like me?

Certain institutions have cornered the market on advertising on military bases, meaning that for many veterans, they either are not familiar with the breadth of high-graduation-rate institutions, or do not think those institutions have any interest in enrolling students like themselves. Veterans who pursue higher education would logically enroll close to home or follow in the footsteps of other veterans, meaning that there is an established momentum toward the schools veterans historically have attended (for-profits, regional publics). Online educational opportunities, which continue to expand and would not require veterans to move to attend school, are also appealing. Unfortunately, these programs do not have high graduation rates either.

Some veteran service organizations (VSOs), such as Warrior Scholar Project (WSP) and Service to School (S2S), are aiming to shift this momentum towards other options. These organizations have sought to increase the number of veterans on the campuses of high-graduation rate institutions through a combination of social networking, advising, and training programming. WSP offers intensive academic boot camps, taught by faculty, and hosted on the the campuses of selective schools with which it partners (Georgetown University, Yale, et. al.). Service to School focuses on admissions advising, connecting prospective students with “ambassadors” who serve as both resources and recruitment officers. S2S has also created an application addendum to help translate veteran experience to admissions priorities (at present, more than 30 schools accept the addendum).

Institutions would generally like to have more veterans in their applicant pools, but often neither know how to generate increases, nor have the resources to reach those students. Before COVID, the College Board launched a promising pilot to allow institutions to search for students based on their CLEP (College Level Examination Program) Exam scores. The exam measures mastery of introductory college-level material and is made available for free to military service members, veterans, and their families. The pilot program never really took off, hampered in particular by the pandemic, which scrambled college preparatory efforts and admissions offices alike. Further exploration of the challenges the program faced, and strategies for overcoming them, could be a worthwhile investment.

How and when should I use my military benefits?

The post-9/11 GI Bill (PGIB) provides education benefits for veterans who served on active duty after September 10, 2001. Maximal program benefits (earned with 36 months of service) cover full in-state tuition and fees at public institutions. For students attending private institutions, or public institutions as out-of-state students, the Yellow Ribbon program provides additional support on an institution-by-institution basis as well as a housing allowance, the amount of which varies primarily by zip code. There’s no time limit on when veterans can use their benefits for their own education.

As noted above, the generosity of these benefits are a primary motivator for joining the military, but the benefits are not unlimited. The GI Bill only provides 36 months of benefits, which need to be used strategically: how many credits a veteran is able to transfer, how long their degree program may take, and whether they may wish to apply their benefits toward a graduate degree in the future, all bear on the choices and timing of utilization. These are substantial decisions that veterans need to make as they consider higher education, some of which are irrevocable. While many online resources offer support, institutions seeking to recruit veterans should do more to help these students plan wisely to make the most of their benefits. Indeed, well-resourced institutions might not require a veteran to utilize their PGIB funds at all. They may cover costs with institutional aid, giving the student the option to disperse benefits to future ends as they wish. In some cases, a veteran might want to save their benefits for graduate school or give those benefits to dependents. Existing data generally does not distinguish between GI Bill recipients who are veterans and those who are dependents of veterans, so it is hard to know the prevalence of benefit transfer. It is crucial to ensure veterans are aware of this benefit, along with all the others, when deciding how to use their benefits.

What should I do with credits that I’ve already accumulated?

Many veterans begin their postsecondary education at community college. Like all students looking to transfer from community college to a bachelor’s degree program (vertical transfer), veterans face numerous obstacles in the transfer process. Among the most vexing of veteran-specific obstacles to this kind of transfer is the limited time use of GI Bill benefits. Additionally, transfer pathways, let alone credit transfer, have been restrictive at many of the high-graduation-rate institutions, creating a potential disincentive for veterans to apply.

Veterans may also have military experience that could translate to college credit. The military service branches do provide transcripts, and the American Council on Education (ACE) has evaluated a variety of experiences to create a Military Guide for institutions to use in considering what credit to award. High-graduation-rate institutions, however, are not likely to accept such credits, creating another disincentive as prospective student veterans decide where to apply and attend.

There may be benefits to starting fresh in a bachelor’s degree program and not seeking to transfer credits, especially for veterans interested in pursuing degree programs that are unlikely to count prior earned credits in unrelated fields. At many institutions that are relatively generous with their institutional aid, first-time, full-time students receive priority, making this route an excellent path to preserving GI Bill benefits even if the time-to-degree may be longer. This trade-off is often not made clear at the time of application, though, leaving veterans unaware of the possibilities available to them, and the implications of their choices.

What support and resources does an institution offer?

Veteran students are often older than “traditional” 18-22 year-old students and, like other adult learners, may have different needs on campus. For example, a veteran may desire housing arrangements that can accommodate a spouse or children. Predominantly undergraduate institutions, however, may not currently be well set up to provide those resources. A student veteran may have a strong interest in a certain institution, but if that institution is not able to support them and their family, veterans are not likely to choose to attend.

In addition to housing and other resources, prospective student veterans may also be looking for a sense of community on campus. This might comprise dedicated veterans admissions staff, a veterans center on campus, and programs like peer mentorship. (The Department of Education has recently doubled down on the value in these resources by launching a grant program to support them). Whether a campus boasts a veterans center, or other forms of student success supports tailored to the veteran population, and how that institution communicates about those resources, is likely to impact veteran enrollment decisions.

What post-graduate outcomes are possible?

College, and the learning that comes along with it, is an incredible experience on its own. But for student veterans and other adult learners, post-graduate career opportunities are essential to the college-going decision. As mentioned above, veterans are more likely to have a family to support, and coming from a prior career (military service), may be inclined to seek immediate workforce opportunities that do not require a degree. The choice to enroll might be thought of as an investment in future earning potential at the expense of present wages, but that choice should be an informed one. Colleges, universities, veterans support organizations, and the military itself, can do more, by way of concerted outreach and advising, to help veterans understand the implications of choosing whether to pursue a degree, what degree to pursue, and where to pursue it.

Different degrees are associated with different post-graduation wages, but in general, bachelor’s degree holders fare better in the labor market than those without a degree, and this advantage is projected to become even more pronounced. Institutional career services offices spend a lot of time thinking about how to support their students after graduation, and have proven success. For many schools, this resource is an important selling point for enrolling prospective student veterans. Institutions can deliver on this commitment by hiring staff in the career services office who focus specifically on the pathway from military service to a post-bachelor’s degree career.

Conclusion

The framework of questions presented here highlights that while the pathway to a bachelor’s degree is nuanced for all students, military veterans experience this complexity to an increased degree. All students share concerns about credit transfer and institutional resources, but the complexity of GI Bill limitations are unique to veterans. Likewise, all students look for community on campus, but veteran communities can be harder to find at many high graduation rate institutions.

As institutions, VSOs, and the military think about the shared, yet disjointed, effort to increase veterans’ access to quality postsecondary education and success once enrolled, familiarity with each inflection point on a student’s educational journey is crucial. As our journey mapping experiment reveals, and the accompanying decision tree visualizes, these steps and questions are highly interdependent. Consideration of one step in the process ought to take into account the whole student journey, and its multiple trajectories.

While the questions developed here are meant to provide a high level view of the key decisions veterans face along a path from service to school, the field could also benefit from deep and broad investigation of the lived experience of navigating this process. The collection of first-hand veteran accounts and the creation of authentic and sophisticated student profiles based on qualitative research could go some distance toward helping higher education and military stakeholders imagine and implement changes to their recruitment, enrollment, and student support efforts, focused on improving outcomes for veterans. This is work that education philanthropies, veteran services groups, institutions of higher education, research and advisory organizations, and the military itself, ought all to be poised to undertake collaboratively.

|