A Georgia Case Study

A Look at the University System Consolidations with an Eye Towards Race, Ethnicity, and Equity

Introduction

Background

While it is clear that not all mergers and consolidations are a success story,[1] and some collapse under backlash from students, faculty, and other community members, the University System of Georgia (USG) has completed an astounding number of successful mergers between its institutions. In fact, USG has “what is likely the nation’s most aggressive and high-profile campus consolidation program.”[2] In 2010, when discussions regarding consolidations began, the university system had a total of 35 institutions “including roughly 10 in parts of the state where the population of 15 – 24-year-olds was projected to decline.”[3] Due to this, the USG began to undertake a series of mergers where administrations were combined, but campuses were not closed. Currently the system has 26 institutions. It is composed of four research universities, four comprehensive universities, nine state universities, and nine state colleges. Former Chancellor Steve Wrigley (he officially retired at the end of June 2021) stated that “the system has proceeded with the clear goal of serving students better. That meant asking how to meet students’ needs and raise attainment levels—questions that conflict with the impulse some state systems feel to protect local interests.”[4]

In 2011, the Georgia Board of Regents adopted a plan for consolidation across its vast system of higher education. The chancellor at the time, Hank Huckaby, originally recommended a total of eight institutions consolidating into four institutions. In fact, the consolidations in Georgia occurred in four rounds (2013, 2015, 2017, and 2018), and combined eighteen higher education institutions into nine institutions. Table 1 includes the names of the original two institutions, as well as the name of the new institution created, or renamed institution, through the consolidation process. This timeline, however, does not show when discussions for said consolidations began; typically, discussions tend to take place years before implementation.

This consolidation movement in Georgia has been well documented and examined by researchers, policy experts, and the media for both successes and challenges.[5] While the successes—for example, the reduction of duplicate programs and degrees—and challenges— such as unexpected costs and clashing campus cultures—have been highlighted throughout the literature, there has been much less discussion or scrutiny of the impact of USG’s consolidations on access and equity for low-income and racialized students.

Table 1: Timeline of University System of Georgia Consolidations

| Year Consolidation Began | Consolidating Institutions |

|---|---|

| 2013 | Augusta State University and Georgia Health Sciences formed Georgia Regents University, which later came to be known as Augusta University[6] |

| 2013 | Macon State College and Middle Georgia College consolidated into Middle Georgia State College, which is now called Middle Georgia State University |

| 2013 | Waycross College and South Georgia College consolidated into what is now known as South Georgia State College |

| 2013 | Gainesville State College and North Georgia College & State University consolidated into what is now called the University of North Georgia |

| 2015 | Kennesaw State University and Southern Polytechnic State University to form the new Kennesaw State University |

| 2015 | Georgia State and Georgia Perimeter College consolidated into Georgia State University |

| 2017 | Albany State University and Darton State College consolidated into Albany State University |

| 2018 | Georgia Southern University and Armstrong State University consolidated into Georgia Southern University |

| 2018 | Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College and Bainbridge State College consolidated into Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College |

This case study will provide an overview of the timeline of the USG system consolidation, rationale(s), and findings about the Georgia consolidation that have not been previously reported on, including: 1) how access and equity for underserved and racialized populations were considered during the formulation and implementation of the various consolidations; 2) the way racial politics and tensions in the state played out during the consolidations, specifically during the consolidation of an HBCU and non-HBCU, and 3) the impacts the consolidations have had on student access and equity. To conduct this analysis, we draw upon published sources and publicly available data, as well as perspectives gained through interviews with both the USG leadership involved in the initial and subsequent consolidation efforts and college presidents who presided over or witnessed these consolidations. Throughout this case study, we will highlight specific cases within the University System of Georgia to provide examples of both the typical and unique ways in which consolidations unfolded and both addressed and neglected equity and access.

Data Collection and Analysis

Unlike many other public university system consolidations, there is a lot of publicly available information, such as enrollment data, as well as scholarly discourse on the University System of Georgia consolidations. Our focus on implementation and racial equity required a comprehensive approach as well as new data collection. Our additional data collection includes valuable perspectives from top USG administrators and executive officers who presided over the consolidations. These new insights provide substantive examples and information about the actual process of implementing consolidations that are rarely captured. We also drew upon available reports and public data from USG, as well as research articles, books, and media sources.

Participants

As previously mentioned, we conducted a number of interviews with key senior administrators (see Table 2 below) who served at the time of the original 2011 USG consolidation policy announcement, as well as USG administrators who have since witnessed a number of consolidations within the system. Finally, we spoke to former and current presidents of consolidated USG institutions.

History

The Georgia higher education landscape is one of the largest in the country, encompassing both public and private, two and four-year institutions. The public higher education system is composed of two large systems, the University System of Georgia (USG), which is governed by the Board of Regents,[7] and the Technical College System of Georgia (TCSG), which is governed by The State Board of the Technical College System of Georgia. Before the consolidations began, the University System of Georgia had a total of 35 institutions.

Prior to any of the consolidations taking place, in 2011 USG had over 318,027 students[8] and conferred 54,855 degrees total annually, including 5,444 associate degrees and 32,397 bachelor’s degrees.[9] In terms of race and ethnicity, prior to consolidation the USG enrolled 127,550 students of color (Black, Hispanic, Asian, American Indian, or Alaska Native, and biracial or multiracial) and 172,879 White students.[10]

Table 2: List of interview participants

| Interviewee | Position and USG Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Tim Renick | Executive Director, National Institute for Student Success; Former Senior Vice President for Enrollment and Student Success at Georgia State University |

| Shelley Nickel | Former Interim President at Gordon College; Former Associate Vice Chancellor for Planning and Implementation for USG |

| Steve Wrigley | USG Chancellor |

| Mark Becker | President at Georgia State University |

| Lisa Rossbacher | President Emerita of Humboldt State University; President Emerita at Southern Polytechnic State University |

| Angela Bell | USG Senior Executive Director for Research, Policy and Analysis |

| Marion Ross Fedrick | President at Albany State University; Former USG Vice Chancellor of Human Resources |

It should be noted that, similar to national trends, Black and Hispanic students were disproportionately represented in four-year state colleges and two-year community colleges, and underrepresented in research universities, in comparison to other race and ethnicity groups.[11] Overall, enrollment in Georgia colleges and universities was down significantly at more than half of USG’s 35 institutions and there was widespread scrutiny in the media about the possible future for the USG.[12]

Finances

At the start of the consolidation movement within the University System of Georgia, there were a number of institutions struggling with enrollment and operating revenue as a result of low enrollment.[13] According to our interviews, this was widely unknown by many of the stakeholders at the institutions, but recognized by the Regents at the time as a major impetus for the consolidation movement in the Georgia system.

A Troubling History of Educational Inequities

Historically, legislators have a very limited role in higher education governance, but the link between the governor and the Board of Regents is very strong. Outside of higher education, with a few exceptions, historically the state of Georgia has been led by conservatives. Race relations within the state have been contentious, largely shaped by a legacy of slavery and Jim Crow policies. There are six Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) within the state of Georgia, all of which were established in the era of de jure segregation. This dual system of higher education was also included in the 1972 Adams v. Richardson case which sought to dismantle a dual system of segregation in 19 southern states.[14] States included in the lawsuit were required to immediately remedy their segregated systems, with the explicit instructions that states create a “viable, coordinated state-wide higher education policy that takes into account the special problems of minoritized students and of Black colleges.”[15] It is also worth noting that prior to the consolidation movement within the USG, the state had taken decidedly clear action on issues related to access and equity for undocumented students.[16] In 2010, the Board of Regents produced stringent guidelines for how USG institutions should tighten their admissions processes to curtail accepting undocumented students in order to address concerns about undocumented students taking seats from documented Georgia students.[17] Later, in 2016, undocumented students launched a lawsuit against USG for banning them from the state’s top institutions.[18] This socio-historical context of the higher education landscape in Georgia has complicated some of the consolidations in the state. We will delve deeper into the case of the state’s only HBCU consolidation, Albany State, in our discussion of how state politics shaped the implementation of that particular consolidation.

Motivations and Goals for Consolidation

According to one of our interview participants, consolidation was a topic of discussion among the Board of Regents for years prior to it officially being enacted. It is evident from the documentation[19] and from our interviews with USG administrators that the Board of Regents was the driving force behind the consolidations. However, several key actors were also named, including Chancellor Hank Huckaby, Shelley C. Nickel, executive vice chancellor for strategy and fiscal affairs, and USG Vice Chancellor for Organizational Effectiveness John Fuchko III. It appears that these individuals were also working on behalf of or in collaboration with the governor at the time, Nathan Deal. As one of the interviewees explained: “[The] Chancellor and board were main proponents. Nothing happens in GA that isn’t also supported by the governor’s office. I don’t think there was a statement [from the governor], but he must have been on board.” For the most part, consolidations in the state of Georgia did not involve legislators, but they did require Regents and accreditation agency approval.

While many consolidation efforts are undertaken to reduce fiscal pressures,[20] the mergers within the University System of Georgia were not solely intended to slash expenses. The November 2011 announcement by the Board of Regents that it would begin a series of consolidations was accompanied by a report highlighting six principles the Board would use to assess consideration of potential consolidations to accomplish particular objectives.[21] These six principles were:

- Increase opportunities to raise student education attainment levels.

- Improve geographic accessibility, regional identity, and compatibility of cultural fit

- Avoid duplication of academic programs while optimizing access to instruction.

- Create significant cost efficiency in service delivery, degree offerings, and enrollment

- Enhance regional economic development through enhanced degree programs, community partnerships, and improved student completion

- Streamline administrative services while maintaining or improving service level and quality.

These six principles are closely tied to the Board of Regents’ motivations, but the prevailing narrative that emerged in most of our interviews with USG administrators was that the overarching goals of the Regents were to increase enrollment, graduation, and student success. There is some early evidence that all of these goals have been achieved to some extent;[22] however, while the USG goals for the consolidations have remained consistent, what is meant by student success may need to be scrutinized to address racial equity.

We spoke to several past and current USG officials who were privy to the initial discussions around the consolidation effort and based on our analysis of our interviews and archival data there was a general agreement that overall the motivations behind the Board of Regents initiating these consolidations fell primarily in four categories: 1) changing demographics and declines in high school graduates (both within the state and nationwide); 2) capitalizing on diverse population growth in the state; 3) improving enrollment and addressing fiscal instability within specific institutions; and 4) reducing the number of duplicate programs between USG institutions that were essentially serving the same community.

While these can be considered the primary overarching reasons for USG’s consolidations, it is important to note that the motivations within this system were not one-size-fits-all; ultimately changing demographics, declining operating revenue budgets, and rising costs emerged as the predominant drivers for the consolidation movement. As a former USG administrator explained:

[We] Looked at demographics, things were changing… we were not enrolling and graduating at the same demographic diversity that was in the state or projected to be. Traditionally, [several institutions] did not do a good job of retaining and graduating [diverse students] …so what do we do, how do we make our institutions more accessible and stable financially?

Like many of our interviewees, this individual shapes a narrative that the consolidations were largely due to a dramatic decline in less well-to-do White students enrolling in the USG, which not only threatened revenue for Georgia institutions but was also related to the way demographics were shifting throughout the state. The potential college-student population was not evenly distributed across the state, consequently although Atlanta, which is much more diverse, continued to thrive and see a boom in enrollment, simultaneously, southern Georgia saw a decline in high school graduates and college enrollment that was linked to a shrinking regional economy. All of the USG representatives identified struggling institutions as a major impetus for consolidation. Struggle can appear in the form of declining enrollment, revenue, or mismanagement of administration and budget.

In Andrew Gumbel’s 2020 book Won’t Lose this Dream,[23] which chronicles some of the evolution of the consolidation movement in Georgia, the impetus for the consolidations is clearly outlined and attributed to the leadership of former USG chancellor Hank Huckaby. According to Gumbel: “Within months of taking office as chancellor, he’d pushed for the consolidation of several of the system’s thirty-five universities and colleges, because they were clustered unevenly around the state and duplicated a lot of administrative functions. The way Huckaby saw it, integrating these functions could free up a lot of money to benefit students more directly.”

Implementation: Consolidation in Process

The way the plan for consolidation in Georgia evolved into policy and was rolled out to institutions reveals a lot about the politics of the state, USG, and the anticipated reaction from stakeholders. Below, we will review how the USG policy evolved, how it was announced, and what plans were formulated to help institutions transition into their respective consolidations.

The Announcement

The discussions leading to the Regents’ 2011 USG consolidation announcement took place in secret, behind the scenes.[24] In fact, due to this secrecy there is a lack of public documentation about the actual development of the consolidation effort. As one former president explained, “It was stealthily done. We knew about these goals and issues months before it was publicly announced. [The] System wanted to curtail advanced discussions and public hearings.”[25] The reasoning behind the secrecy was to avoid contentious and drawn-out discussions from stakeholders who would object or would desire to engage in extended deliberations about the need for consolidations thereby dragging the possible implementation out.

The discussions leading to the Regents’ 2011 USG consolidation announcement took place in secret, behind the scenes.

As with the initial announcement of the consolidation principles, the preparation for each round of consolidation was carried out in secret to avoid protest and controversy. This strategy mostly achieved those goals over four rounds of consolidations. But in the case of the consolidation of Kennesaw State University and Southern Polytechnic State University, it may have backfired. Roughly a week before the consolidation, the Regents conducted a vote in a confidential closed session meeting. While it was the third consolidation to take place in Georgia (see Table 1), it was the first consolidation where neither president from either of the institutions involved in the consolidation had plans to retire or to resign. As Lisa Rossbacher, the former president of Southern Polytechnic University, explained in an interview, “It caught me off guard because neither of us were leaving. I was told two weeks beforehand that the other president would be the president and that the name of the other institution would be the name of the new consolidated institution.” As a result, Rossbacher described how she had only minutes after the public announcement about her institution’s consolidation to prepare to address questions and concerns from faculty, staff, and students. She described doing this impromptu to a large crowd bubbling with anxiety and confusion. Eventually the announcement of consolidation led to very public backlash and protest that captured the attention of the press.[26] As she explained:

I worked with the students, who felt unheard in the entire process; their concerns were not addressed. I had to help students understand about politics and process. Some decisions were right, but the execution was wrong, and the students focused on what should have happened.

Similarly, the secrecy of the planning and vote to consolidate Albany State University and Darton State College, and the limited communication with stakeholders, may have generated some unnecessary tension. Once approved, that consolidation was communicated through a press release and then through word of mouth. This created different rumors about the purpose of the consolidation.[27] Eventually, USG representatives had to visit the campuses to explain the purpose of the consolidation, citing the close proximity of the two colleges and Darton State College’s resource deficiencies related to shrinking enrollment and financial instability. As a result of these negative reactions, USG administrator had the following advice for including stakeholders:

Don’t underestimate and don’t devalue people’s feelings about this. Easy to get caught up in the data and theory, but for people in communities it’s about local institutions and how they relate to the community. There’s a human factor around cultural and emotional attachment to institutions. Knew that going in, but going through the process reinforced the importance of respecting that. Second thing is you can’t say enough why you’re doing something TO them, that’s the way they see it. Have to repeat all the time why we are doing this. Needs to be simple, clean, clear.

Consolidation Process

The planning for each of the consolidations that occurred took approximately 12-18 months, and some would argue that work is still ongoing in terms of creating a cohesive and unified new system. According to all of our interviews, the Board of Regents did not offer much detail about how to implement the consolidations, leaving the actual consolidation plan up to institutional representatives each institution. USG instituted a process that would ease some of the challenges of coming from two different institutions. In order to create a collaborative process that took the needs and considerations of both consolidated institutions into account, USG mandated that each consolidation be guided by a designated consolidation committee. The goal of the consolidation committees was to implement the consolidation plan, attend to efficiency, and eliminate duplication within the consolidation. Although there was some indication that not all planning pertaining to the consolidations happened in committees. For example, as Andrew Gumbel described about the GSU-Perimeter consolidation committee, “Theoretically a lot of [consolidation] issues were to be hashed out by the consolidation committee…. really though, the conversation started before the committee had a chance to hold its first meeting.”

This quote raises a troubling issue, especially as it pertains to equity and input in the consolidation process: Who was invited to these early conversations, who was excluded, and were the committees really functioning as a space for collaborative planning or as a symbolic gesture?

In addition to appointed institutional leaders and administrators from both campuses, consolidation committees were also comprised of subcommittees designed to strategically address crucial areas such as IT, branding, academic standards, recruitment and promotion, and other critical areas.

From discussions with administrators at USG as well as former executive leaders overseeing these consolidations, we found that the purpose and usefulness of these committees were greatly contested. Some leaders we spoke to, such as those at Georgia State University, felt that the transition committees were effective and helpful towards the consolidation effort and process.[28] However, other accounts did not have the same positive feeling about these committees. Some individuals who we interviewed felt that the committees lacked collaborative effort. As the previous president of Southern Polytechnic State University elaborated, “I didn’t find the [consolidation committee] meetings effective because I quickly realized that my presence was being used to legitimate changes [the Kennesaw stakeholders] already wanted to make.” The president of Albany State, who is a former USG administrator sent to oversee the consolidation process, also described the negative side to the consolidation committees, stating that they were thwarted by the embedded stakeholders on the committees still upset, or in a state of denial, about the permanence of the consolidation process. Eventually this led to a lack of progress and ideas that never materialized. In reality, many of these committees failed to bridge the gaps in cultures of the institutions involved in the consolidation process.

Stakeholders Reactions

Concerted efforts of the Board of Regents to create a webpage to address the benefits and challenges of each consolidation,[29] and our interviews indicate that the stakeholder reactions were very passionate, contentious, and ultimately shaped the way the consolidation process was implemented.[30] Over the past several years, there have been several articles about stakeholder backlash to various consolidations.[31]

When we had the chance to speak to several current and former USG administrators, they revealed that this in fact was an anticipated reaction. As previously mentioned, this was one of the primary reasons why consolidation discussions and decisions were made in secrecy behind closed doors well before they were announced to the public. Some USG officials blamed the backlash to consolidations on a resistance to change but felt that ultimately stakeholders saw the benefits: “Most of the time, people don’t initially embrace it, they don’t like change. The first consolidations have pretty much simmered down by now eight or nine years later. People in the community generally react ok—they see the opportunity, like expanded program offerings.”

Some administrators we spoke to acknowledged that while many stakeholders of consolidated institutions, especially those who lost their institutional names, were not happy about the consolidations, they ultimately became resigned to the change because the Regents’ policies could not be contested. As one administrator explained, “stakeholders of the institution that doesn’t keep its name…are more disgruntled. I would be surprised if that wasn’t the case. The Regents have constitutional authority, and so their say goes. There were op-eds, etc., but no one questioned [their] authority to do it.”

Implementation Challenges

There appears to be universal consensus that many of the consolidation plans did not evolve as planned, largely because the detailed planning required for consolidation was left up to the consolidation committee of the individual institutions in the consolidation process. Several challenges arose during the implementation of the consolidations that ultimately shaped the way they unfolded. These challenges included things like faculty and student resistance, technology, branding, and the unexpected details that come with wrestling with how to create and reconcile new and old processes, symbols, campus culture, and ways of doing business.

Resistance

One of the most prominent challenges that emerged in our analysis of both archival data[32] and in our interviews was resistance from faculty, students, staff, alumni, and community stakeholders. In fact, resistance was so strong that many of the consolidations in Georgia frequently caught the attention of the media. Many of the people we interviewed admitted that one of the reasons why deliberations about consolidations happened in closed USG meetings was to curtail inevitable backlash but it is clear that the Board was not prepared for the way the backlash would soon morph into outright resistance. Consequently, the implementation process was often stymied, and lingering tensions remained in some sectors of consolidated institutions.

One of the most prominent challenges…was resistance from faculty, students, staff, alumni, and community stakeholders.

The most disruptive elements that significantly stalled or altered the consolidation appear to be the merging of similar departments. Our interviews revealed that while the departments may have shared similar disciplines, each institution had very different cultures. Additionally, according to administrators there were issues with power and status that included resentment from some faculty about the changes being made and complaints that the more prominent faculty and administrators from the healthier institutions were making changes without attempting to understand the struggling campus’ culture and perspective.

…resistance was steeped in the racial dynamics and perceived differences between the two campuses.

Other forms of resistance resulted in active resistance to even changing the name of the institution and attempts to sabotage any efforts to streamline and rebrand or rename the consolidated institution. Some of this resistance was steeped in the racial dynamics and perceived differences between the two campuses. As one administrator explained, Darton State College faculty did not see themselves as part of Albany State: “They see it as a step down because of race, even though the students look exactly the same, but it’s the association with an HBCU. [Some stakeholders] had senior leadership ask to drop the HBCU designation.”[33]

“They see it as a step down because of race, even though the students look exactly the same, but it’s the association with an HBCU.”

According to Marion Frederick, the current president of Albany State, the long legacy of HBCUs as educational sites for underrepresented and disadvantaged students of color is often unfairly and incorrectly associated with lower prestige and academic excellence. This perception seems to be tied to requests to dissociate the newly consolidated institution from the HBCU designation, even though Albany State was ranked higher than Darton College and had a more competitive student body and admissions standards.

Resistance to the Albany State and Darton College consolidations manifested from all sectors—students, faculty, staff—and some of it was very passive, presenting in the form of non-participation and disengagement. At times, this disengagement was very strategic, designed to thwart efforts to support a successful consolidation. One of our interviewees expanded on this slightly by describing “[We were] over a year late in preparing for that SAACS [accreditation] visit. [People thought that] if we’re not accredited, then the separation would happen. Another example is the state of Georgia has a common application so a student can apply for admissions. We decided not to pull any applications from that site and when forced to, we had a worker who tried to hold those applications hostage.”

Resistance emerged in a different way during the Kennesaw State and Southern Polytechnic consolidation. This pushback came in the form of overt protest and declarations of disapproval. This is closely connected to the sudden (and for most surprising) way the announcement about the consolidation occurred. The administrators we spoke to described student protests, letters to the Board, and stubborn denial that the consolidation would last. As one administrator explained “Everyone went through the five stages of grief. Denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. I think some people are still going through this. People were angry and denying it couldn’t be reversed.”

In the case of the GSU and Perimeter consolidation, there wasn’t a lot of pushback, except from the outgoing president of Perimeter who filed a lawsuit against the USG for being ousted from his position. However, GSU president Becker described that while there was no strong protest, there was a lot of fear.

People had questions like what was the consolidation going to do to GSU? Is this going to bring us ‘down’ in terms of rankings, etc.? Perimeter staff feared that it would take away [its] access mission. There was a fear that they would want to change everything, however, we haven’t changed curricula, education standards.

To combat this fear, GSU carved out a space that was uniquely Perimeter, with Perimeter faculty, students, and tenure guidelines. In our discussions with other presidents who oversaw consolidations, similar efforts were made to quell concerns and fear. One of the lingering questions though is whether this solution is true consolidation or a concession, and to date there have been no studies on the long-term impact of this kind of model for stakeholders who were previously resistant or leery of the consolidation.

Systems and Technology

One of the major challenges that continuously emerged in our interviews was the issue of how to streamline and make adjustments to system wide processes, particularly processes related to the business of doing higher education, such as human resources, admissions, and administration related to procurement and payments, and deciding on what technologies and platforms would be used to execute these processes. For each of the consolidations, there is a long list of tasks that need to take place for the larger efforts to be successful. Many have to do with merging data systems and practices. For example, one of our interviewees spoke about the difficulties of bringing a record keeping system together stating that “there were many instances where students had the same names but eight years ago for privacy issues, the college mandated that we couldn’t use SSN so we needed to merge on student ids. Glitches raised 70-80,0000 common merge issues and concerns of privacy (like someone receiving the wrong transcript). Trying to bring systems back together was a particular challenge compared to other consolidations.” Difficulties with technology and merging different systems was also a major issue that came up in the Albany State University consolidation.

Increased Spending

While some consolidations saved money by reducing duplicate programs and positions,[34] improving efficiencies in some areas required greater administrative support and, in some areas, more specialized higher education professionals.[35] This resulted in an initial increase in spending; as one USG administrator put it, “GA consolidations didn’t really save money—just redirected money into different things to support the academic mission of the institution. Consolidation is not an easy answer in the short term. There are just a whole lot of expenses upfront that make it a short-term loss, if anything.”

Rebranding and Retaining Identity

Many of the expenses in a consolidation are related to rebranding. Consolidated systems have to either cast a wider net to expand one institution’s name onto another institution, or they have to rename everything across two systems. In addition to the costs of rebranding, there is the tricky dilemma of maintaining alumni ties for fundraising. As one of our participants elaborated, “Each institution has an external foundation that is the fundraising arm, and merging those was challenging in some circumstances, because donors identified with the pre-existing institution.”

Many of the expenses in a consolidation are related to rebranding. Consolidated systems have to either cast a wider net to expand one institution’s name onto another institution, or they have to rename everything across two systems.

This can be especially difficult when the two institutions consolidating have very different rankings and reputations. In the case of the GSU-Perimeter consolidation, there was the perception that for some disciplines and degrees the GSU name had more value. As one administrator explained, this “played out in different ways, for the most part, the Perimeter students were supportive since GSU had a better brand/reputation. That wasn’t the case for Southern Polytech-some students felt that their tech degree was more valuable than the Kennesaw branding…at GSU, students are unsure if it would devalue a degree.”

Rebranding and maintaining pieces of each institution’s identity was particularly troublesome when merging the historic HBCU Albany State University with Darton State College. According to our interview with the current Albany State University president, there were deeply loyal stakeholders at each campus who refused to accept the longevity of the consolidation effort. This led to an active campaign of outreach on her part to educate stakeholders about the institutions they were consolidating with and how they might fit together. However, through this process they were reminded that even if consolidated, some distinctive parts of Darton State College were not going away. As with the case of the GSU-Perimeter consolidation, whether this is ultimately a good outcome remains to be seen and needs to be examined further. The issue of being associated with a HBCU and the inherent deficit racial biases that were brought to light complicated the implementation of the ASU-Darton consolidation in ways that were not evident in other Georgia consolidations. We discuss the racial politics and the way they shaped this consolidation effort in more detail later in the paper.

Clashing Campus Cultures

One of the most prominent challenges identified during research and throughout interviews was reconciling different campus cultures. As one participant explained: “always very hard to combine cultures; when missions differ, there are different populations of students, and it can be challenging to make sure you are serving all those populations equally well. Makes for difficult conversations about how to use a pooled set of resources. People on campus had to work incredibly hard to make these work, and there was no extra money.”

Clashes in campus cultures were also particularly contentious and challenging in consolidations involving two-year community colleges and four-year colleges.

Clashes in campus cultures were also particularly contentious and challenging in consolidations involving two-year community colleges and four-year colleges, institutions with vastly different missions (i.e., the medical college and four-year college, HBCU with non-HBCU), and institutions with different academic standards.

The culture of an HBCU is something that is often identified as unique. This became evident in the consolidation efforts to bring together Albany State University and Darton State College. This consolidation highlighted the marked differences and difficulties of trying to bridge two institutions with distinctive different cultures. As one administrator explained, combining an HBCU with a non HBCU in southwest Georgia: “It was like we’re married, but people kept asking ‘when is the divorce coming?’”

The tumultuous marriage analogy is also fitting for the Kennesaw State University and Southern Polytechnic State University consolidation, where culture clashes between the campuses appeared to lead to stakeholders seeing the worst in the other campus, creating significant challenges for senior administrators and Human Resources. As one participant explained:

People with a vested interest in how [the consolidation] turns out, keeping jobs, keeping people around, makes it more difficult…. From the HR standpoint, organizational change, culture change, understanding the cultures. How you set the culture is how you treat people.

The Unexpected

The leaders who spoke described unexpected issues that arose during the consolidation process that had to be addressed promptly. This led to additional work, with the implementation sometimes requiring just as much moral support as technical support. As one interviewee put it, “there’s a lot of extra work involved in consolidation. Be[ing] there to listen, talk through concerns and support one another morally is something that is required in this arduous process.”

Managing these unexpected challenges—along with the others highlighted in this report—takes time. While the USG strategic plan for consolidations allotted 12-18 months, the consolidations tended to take much longer, and some are even still under way, years later.

Impacts and Outcomes

While some of the challenges of the consolidations have been acknowledged by the Board of Regents and dissatisfied stakeholders, there have been successes and positive impacts, much of which have taken up a much larger narrative in the media and the Regents’ communications. For each consolidation, the USG website notes challenges, but dedicates a much larger space to highlighting the successful outcomes and impacts of each reorganization. There have been many scholarly examinations of the effects of the USG consolidations. The successes have also been highlighted by the media, popular higher education periodicals, and Andrew Gumbel’s newly released book. Most notably, the GSU-Perimeter consolidation stands out as a remarkable accomplishment in improving equitable outcomes for students. Below, we discuss the most prominent areas of success and impact in two ways—direct organizational consequences of the consolidation and indirect outcomes that cannot wholly be attributed to the consolidation but nevertheless manifested after the consolidations occurred.

Direct Organizational Consequences of the Consolidations

Increased Access and Transfer. With previously strong transfer ties between GSU and Perimeter, consolidating offered a more streamlined pathway from community college to a four-year degree. Prior to the successful consolidation, students needed to formally transfer, but now they transition into other colleges, which has been an advantage to students. After the consolidation was completed, students who originally started at Perimeter were already considered GSU students, so the transition was more seamless because they were already part of the community and had access to GSU services. This greatly improved access to four-year degrees for first generation students and those from lower-socioeconomic backgrounds.

Improved Focus and Support for Student Success. Ultimately, most of our participants felt that the consolidations resulted in creating more resources for student success. Lauren Russell also found that overall, the USG consolidated institutions shifted spending from student services to academic support in such a way that overall spending was unaffected.[36] The renewed focus on student advising and student services also had a positive impact on students. As Steve Wrigley explained “Institutions are on more solid ground, more program offerings available to more students. As Independent study found that students did better after the consolidations—the reinvestment of administrative expenses into student supports helped students succeed.” This point was expanded when we spoke to Marion Ross Fedrick, the current president of Albany State University, “we were able to mobilize resources for student access. More tutoring (study tables, where faculty will teach class with syllabus, extra help), tying data to all of this. Retention rates are going on considerably better.”

Streamlining and Reducing Duplication. Most of our interviews highlight that the consolidations reduced duplication of program and administrative staff, especially for geographic areas where there were two institutions offering similar degrees. Many of our interviews also identified a reduction in administration so that those resources could be directed to student services and academic success. This is also highlighted in literature we examined.

Uncertain Impacts and Successes

Increased Retention and Graduation. There is some evidence that the consolidations have resulted in increased retention and graduation rates.[37]

The USG consolidations increased retention of first-time undergraduate students by four percent.

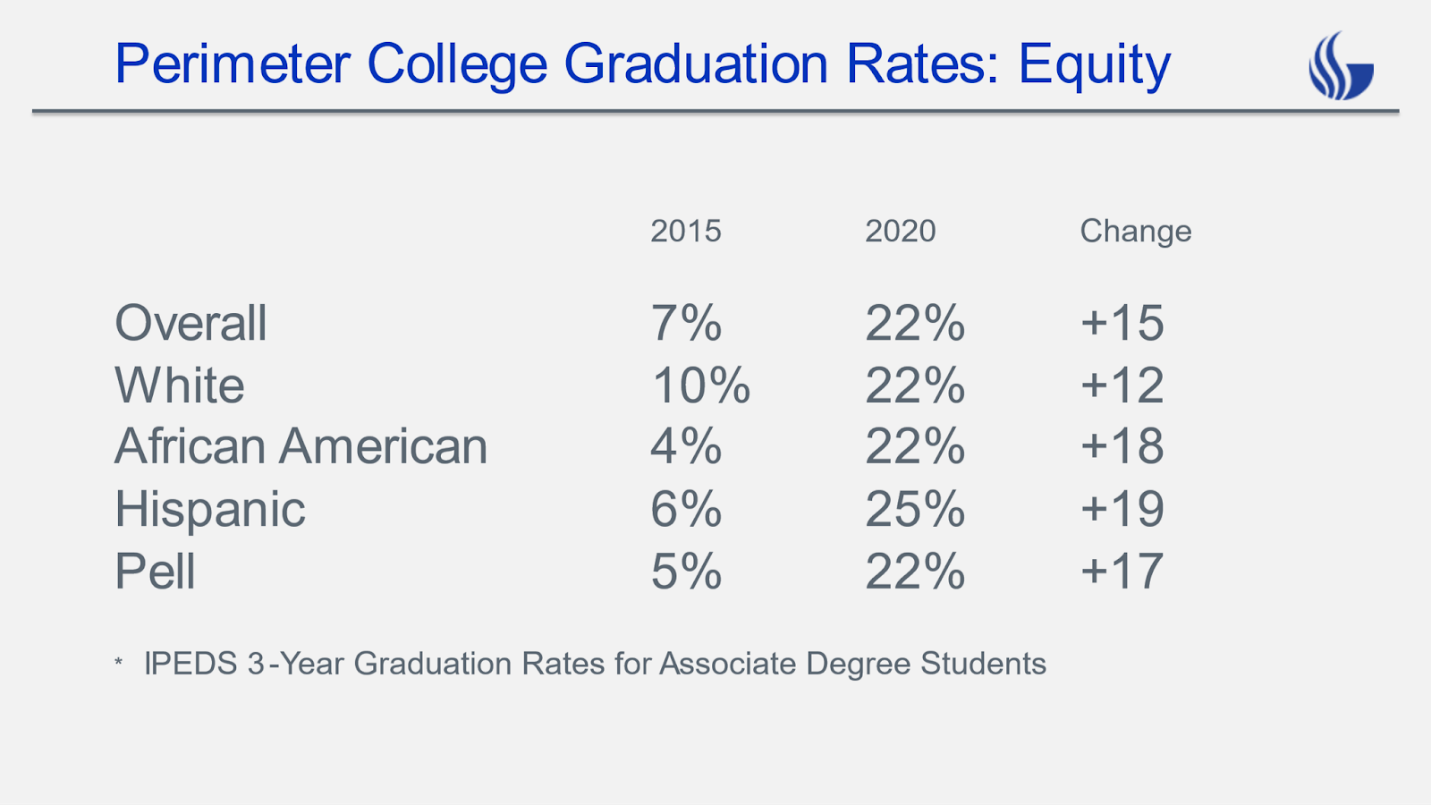

Using a differences-in-differences statistical design comparing student retention and graduation outcomes for cohorts enrolling just before and just after consolidation, the USG consolidations increased retention of first-time undergraduate students by four percent.[38] In fact, in the same study, it was also found that there was an eight percent decline in first-year dropout. This finding was echoed by several of the USG senior administrators and presidents that we spoke to. The president of the GSU-Perimeter consolidation, Tim Renick, said that there has been noticeable graduation improvement, in particular among Black students. As he explained “White students were graduating one and a half times more than Black students, but Black students are graduating at around the same rate now after 5 years.” The data confirms this and also highlights that there were significant gains among all student populations after the consolidation. As of 2020, Perimeter College ranked 20th in the nation for student success among two-year colleges.[39]

Figure 1: Perimeter College Graduation Rates by Race and Ethnicity[40]

Graduation rates improved as well. In 2020, USG had conferred a total of 70,879 degrees, up roughly 29 percent from the 2011 total of 54,855 degrees. This growth included a dramatic increase of over 10,000 more bachelor’s degrees in 2020 in comparison to 2011.[41]

Increased Enrollment. While there may have been an initial decline in enrollment due to backlash and resistance, ultimately, most of our participants felt that the consolidations resulted in more robust enrollments. In fact, according to the USG system data reporting, enrollment within the USG rose each year, starting at 321,551 in fall 2016,[42] and growing roughly six percent to 341,485 in the fall of 2020. While the total enrollment for the USG system in 2011 was 318,027, by 2018 the total fall enrollment for the system was 328,712, which reflects an over three percent increase.[43]

Many of our interview participants reported that enrollment was up for the individual consolidations as well. While this has not conclusively proven to be the result of the consolidations, it is mentioned frequently by those who see the consolidations as successful, even at institutions where the consolidation efforts were challenging. For example, at Albany State University, the animosity and disenchantment with the consolidation initially caused an eight percent drop in enrollment in the 2017 – 2018 academic year.[44] However, it has since recouped with an uptick recorded for the 2019 – 2020 academic year. As of 2020, the newly reorganized ASU has seen an increase from 3,000 to 6,500 students.[45]

But while these accounts offer promising evidence that the USG consolidations produced positive effects for students, there are some significant caveats. Lauren Russell admits that while overall, her model shows positive effects, not all the mergers were similarly effective in increasing retention rates.[46] Most importantly, the effects of Russell’s model were driven by students with the strongest pre-college qualifications, so her model may not fully represent or even capture how the consolidations impacted students who are underprepared and more likely to be first generation, students of color, and students from low-income families. This also underscores one of the primary challenges to understanding the true impact of the consolidation efforts in Georgia.

The Data Problem

Georgia presented some unique challenges that complicated the implementation and measurement of the impact of the consolidations. While there is some evidence that many of the Regents’ desired goals for consolidation were realized, there are some goals that remain elusive or, at least, hard to assess, and finally some potential unintended consequences of the consolidations.

Prior to the consolidations the USG enrolled 127,550 students of color…as of 2020, the system now has 175,181 students of color enrolled (Black, Hispanic, Asian, American Indian, or Alaska Native, and biracial or multiracial). That is more than a 47,000-student increase, or articulated differently, more than a 37 percent increase in students of color in a nine-year time frame.

There were varied responses about the impact of the consolidations on student success. While some of the administrators we spoke to claimed triple graduation rates and equal graduation rates between Black and White students, others were more hesitant about claiming any significant impacts. This may be largely due to the fact that some of the reorganized institutions are still working through the consolidation process. As noted previously, in 2011, prior to the consolidations the USG enrolled 127,550 students of color. As of 2020, the system now has 175,181 students of color enrolled (Black, Hispanic, Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, and biracial or multiracial). That is more than a 47,000-student increase, or articulated differently, more than a 37 percent increase in students of color in a nine-year time frame. There was also a decline in White student enrollment from pre- to post- consolidation reorganization efforts, from 172,879 in 2011 to down to 160,670 in fall 2020.[47] However, these numbers only tell a partial story. While every consolidated campus is required to post data annually on campus enrollment, the actual impact of many of these consolidations may not be evident for years to come. Even in cases such as the Perimeter and GSU consolidation in which information on student success are disaggregated by race and Pell eligibility, there may be other factors that complicate drawing causal inferences from the consolidations on enrollment and graduation.

There have been some studies investigating the success of the consolidations, but none of them prove a direct correlation between the consolidations and outcomes; the data are muddled by extraneous variables such as other initiatives, programs and extreme fluctuations in the economy and migration in and out of the state. As Dr. Angela Bell, the current USG senior executive director for research, policy, and analysis, emphasized, “as you observe trends, it seems like institutions have done better on retention and grad after consolidations. But it is hard to parse out because of other student success efforts…. We continue to get asked to provide info on what enrollment, grad, retention look like on a historical trend. It’s hard to point to what the consolidation is doing versus other factors. But it is monitored. I haven’t seen examples of consolidated institutions tanking when others are doing better. It’s usually pretty inconclusive.” During our interview, Dr. Bell went on to explain that while she has examined the consolidation data and equity data, there has been no clear strategy identified for how to look at the two of those things intertwined with each other: “[I’ve] produced a lot of dashboards for internal use that cover all sorts of intersectionalities, but can’t really make those public because of small cell sizes, so it’s difficult to examine the intersection of consolidation and student success by student characteristics.” The current president of GSU was confident the consolidation effort had made a positive impact on graduation rates, particularly among Black students,[48] and there is data to back up his enthusiasm. For example, the newly consolidated GSU saw positive and significant impact on graduation as well as interim measures of success in retention for Black students seeking associates degrees, two times the rate as other students.[49]

The current president of GSU was confident the consolidation effort had made a positive impact on graduation rate, particularly among Black students.

Despite this promising data however, when it came to the challenges of parsing out the impact of the consolidation via data, he noted that there are some tricky dynamics at play, particularly when it comes to reporting data. As he explained: “Perimeter campuses report data separately to IPEDS, which has required all sorts of gymnastics.” Marion Ross Fedrick, the current president of Albany State University, also echoed this difficulty when looking at data as a success metric for the consolidations: “there have been general increases in student retention and graduation—can’t attribute directly to consolidations.” One of the most telling examples of this data tracking problem comes from the GSU-Perimeter case study. “Perimeter wasn’t tracking students, so there was no way of knowing how many of the 94 percent who did not graduate were satisfied taking just a handful of classes….or enrolling in college elsewhere…and how many were simply giving up.”[50] While this is not directly related to consolidations, because it is a reality for almost all community colleges, which enroll non-degree seeking students, it complicates how to disaggregate, track, and make claims about the impact of consolidations.

Our interview with a former executive administrator at Southern Polytechnic underscored how data can get lost in a consolidation, especially when departments and programs are combined: “It would be difficult to track the numbers because, for those students who got absorbed into a larger institution, the data would be hard to combine; the data would have to be tracked down to a departmental level. It’s really complicated trying to disaggregate now. Southern Polytechnic had a number of discrete majors, but data for students majoring in subjects like English, biology, and chemistry would be impossible to disaggregate.”

While the challenge of data tracking may not be unique to the case of Georgia, the state’s socio-historical context is, and gave rise to distinctive racial politics during a few consolidations.

Racial Politics and Tensions

Georgia has a long and complex history related to race. As one of the largest original slaveholding states in the United States, the legacy of Jim Crow segregation and state sanctioned disenfranchisement today still shapes the politics and relationships between different groups of stakeholders as well as the way different institutions are perceived. Nowhere is this legacy more prominent than the presence and number of HBCUs in the state of Georgia. HBCUs are a direct product of the Jim Crow segregationist system, and these institutions are held sacred by the Black community, which can make the topic of consolidation even more politically charged. As Tim Renick explained “The Georgia system is uncommon in that there were 6 HBCUs- initially the idea was that they were off limits. The thinking there was that there were too many political concerns to converge HBCUs with non HBCUs, [except for] the more recent one [involving Albany State and Darton College]. [T]here was an idea that Albany state would remain; there was no new renaming so there were no political issues since the HBCU retained its name.” This perspective contradicts our findings about the pushback and politics that arose over the consolidation of Albany State with Darton.

HBSCUs are a direct product of the Jim Crow segregationist system, and these institutions are held sacred by the Black community, which can make the topic of consolidation even more politically charged.

As an HBCU, the Albany State-Darton College consolidation highlights the uniquely complex and contentious racial politics of Georgia. According to the current president, Marion Ross Fedrick, the consolidation pushed uncomfortable conversations about race and perceptions of equity. Ironically, at the time of consolidation, Darton State college was a majority minority institution, with a large African American population, although the faculty was majority Whiteat the time. President Fedrick said that while Albany State was the higher-ranking college, there were concerns from some at Darton that being consolidated with an HBCU would bring down the reputation and quality of education. There were, and to this day still, some Albany State faculty members who were concerned with the way a more open access institution with lower admissions requirements, like Darton, would affect the ranking of Albany State, which was formerly one of the highest ranked HBCUs in the country. So, each institution was concerned about the other affecting their reputation and standards. Not only were these issues complicated, but they were very much racialized due to the community’s perceptions of the two institutions. President Fedrick provided an example of how this played out when it came to stakeholders: “I talked to a guy who said why did they mess up things, they had a Black school and White school.” According to Ross, as a result of the consolidation, the man said he will not put an ASU sign in his yard or any of his businesses. Ross indicated she is not sure this perception will change in her lifetime, but the consolidated institution has to keep its focus on enrolling quality students and doing good things. In this case, the stakeholder was supportive of the HBCU Albany State only when it was separate from Darton, which they perceived as an institution for White students, despite the fact that Darton had a substantial non-White student population.

While the Albany State-Darton consolidation presented a clear example of the way racial politics in Georgia could complicate the implementation of a consolidation, there were other, more implicit examples of racial politics at play in the state, namely in the case of the Kennesaw-Southern Polytechnic consolidation, as described below.

Absorbing Diversity

At the time of the Kennesaw State- Southern Polytechnic consolidation Southern Polytechnic routinely ranked number one or two in the country for African Americans pursuing a bachelor’s degree in engineering related fields.[51] Kennesaw was a thriving predominantly White institution. The consolidation meant immediate diversity for the newly consolidated Kennesaw. However, in our discussions with the former president of Southern Polytechnic, there was concern that the cultural environment that nurtured a robust African American student body at Southern Polytechnic would not be cultivated by Kennesaw: “For years, the president of the Student Government Association (SGA) at Southern Polytechnic was African American, and that had a lot to do with creating a critical mass of African American students on campus. It was connected to the local chapter of the National Society of Black Engineers which has some great leadership development programs for students. A number of SGA presidents had come out of those student leadership development programs.”

This issue of absorbing diversity and tracking what happens to the minoritized students who get absorbed in a consolidation is also directly related to the challenge of tracking data pre and post consolidation. This was also reflected when it came to specialized programs and scholarships. The former president described a Southern Poly endowment designated for Hispanic students that was created during a time when there was a lot of anti-Hispanic and anti-undocumented immigrant sentiment, and USG wouldn’t allow undocumented students to register at some of the individual institutions. She went on to explain that she is unsure what happened to that endowment or if the requirements for awarding it had changed as a result of the consolidation.

The issue of absorbing diversity and tracking what happens to the minoritized students who get absorbed in a consolidation is also directly related to the challenge of tracking data pre and post consolidation.

Inevitable campus culture classes are exacerbated when race is a salient component of an institution and there is resistance or hesitancy to address race during the consolidation. Albany State’s president highlights how “combining the two [institutions] was the right thing to do, but the biggest losers were students. You can still feel it in the air, there was a lot of racial duplication so as not to go through the process of organizational change. Code names for things. Co-dean to duplicate the role, not to step on anyone’s toes. Almost like a pause for a couple of years, I don’t want to offend you, and I don’t know how to do it without offending. We had to be braver and say this is how this should be set up.”

In the case of Kennesaw State and Southern Polytech, specialized programs, activities, and scholarships formerly utilized by minoritized students were absorbed but not necessarily tracked or monitored, which left a gap in knowledge about whether or not the consolidation displaced or even erased theses supports for specific groups of minoritized students.

While USG consolidations do highlight some real successes in the areas of student support and in some cases outcomes, without a clear grasp of the pre-consolidation data, there is no real way to capture how students of color may have fallen through the cracks and/or decided not to enroll in the new consolidated institutions. More than a few of our participants admitted that initially, enrollment declined shortly after the consolidations, only to recoup later. In the case of Kennesaw State and Southern Polytech, specialized programs, activities, and scholarships formerly utilized by minoritized students were absorbed but not necessarily tracked or monitored, which left a gap in knowledge about whether or not the consolidation displaced or even erased these supports for specific groups of minoritized students.

Lessons Learned

The Georgia consolidations are among the most studied cases of consolidations, largely because they took place over a number of years and involved so many institutions, 18 in total. Based on the publicly available documentation, media coverage, scholarly inquiry, and the information gained from our interviews, we have gleaned many lessons from the Georgia consolidations, which we review below.

- States that wish to pursue consolidation should include a plan for supporting institutions and the transition team throughout the implementation process. State systems must provide support, information, and resources for consolidation implementation to institutions. Both former and current administrators reflected on the ways in which the University System of Georgia could have better prepared and assisted some of the institutions throughout the consolidation process. Whether or not external support was offered by USG at the beginning of a consolidation, eventually it became apparent that system support was needed during the implementation phase, especially as this was often where challenges arose.

- Consider stakeholder perspectives. One of the ways states can mitigate some of the backlash and resistance that inevitably arises during a consolidation is to plan for ways to incorporate stakeholders. People with a vested interest in institutions set to be consolidated want to be heard, they want transparency about what is happening, and they want to know why change is occurring. While USG officials were insistent that the secrecy and swiftness of the announcements helped curtail some of the fallout, or a long protracted political discussion, many of our interview participants felt that the best way to address and alleviate stakeholder concerns was to give them an opportunity to speak and be heard.

- Consider and plan for institutional culture clashes. The Georgia Board of Regents’ website, and our interviews confirm, that one of the inevitable sources of conflict and struggle in the consolidation process is the clash that occurs when two different institutional campus cultures are brought together. Each campus/institution has a distinctive student body, traditions, symbols, and rituals that have forged a unique culture. Successful consolidations take both cultures into consideration and try to find a way to honor them in the new consolidated institution. This is, of course, easier said than done.

- Consolidation costs more money initially, but can lead to a reduction in duplication of administration and programs. Through our research and interviews we learned that in the short run, contrary to popular belief, consolidations do not save money. In fact, the process of consolidation generates new expenses associated with rebranding, establishing new processes, technologies, human resources, and much more. Despite these short-term expenses, many of our interviewees, many years after their consolidation, do still hold out hope that the act of consolidating will ultimately lead to savings by reducing duplication in programs, streamlining processes, and reinforcing efficiency. However many of our participants emphasized that these savings lead to redirecting money towards other priorities like student academic support.

- Consolidations can save institutions struggling with finances and enrollment. Consolidation can help institutions that are experiencing declining enrollments by strengthening staff, faculty, and resources when combined with a healthier institution. Combining resources and staff can create more expansive and diverse programs and departments and help administration streamline services to target student needs.

- Implementing a successful consolidation is a complex and long process. Successful consolidations take time. States proposing consolidations should consider this a long-term project and plan for providing support throughout the implementation process. It is important that states remember that the actual impact of a consolidation may not be evident until years after the consolidation takes place.

- Students of Color can get left behind. An initial dip in enrollment is something states need to consider and anticipate when consolidating. Having a plan for mitigating possible unintended negative impacts on students may prevent an enrollment decline and/or institutional barriers that can curtail student retention and success in the early months of a consolidation.

- Supporting equity and equitable outcomes requires strategic planning and reliable data. One of the most important take-aways from this case study is that unless it is prioritized and planned for, equity can get lost in the consolidation process. This is particularly true when it comes to tracking data for minoritized students. Enrollment numbers, specialized affinity programs and scholarships, and specialized services tailored for minoritized populations prior to consolidation have to be protected and monitored so that they aren’t lost or forgotten in the consolidation. Without targeting and tracking equity goals and supports, any potential gains may only reflect an incomplete story, or worse may not even be realized at all.

Endnotes

- Emma Whitford, “University of Alaska Scraps Merger,” Inside Higher Ed, August 7, 2020, https://www.insidehighered.com/quicktakes/2020/08/07/university-alaska-scraps-merger. ↑

- Matt Zalaznick, “Georgia Leads College Consolidation Movement,” University Business, February 2015, https://universitybusiness.com/georgia-leads-college-consolidation-movement/. ↑

- Rick Seltzer, “The Merger Vortex,” Inside Higher Ed, August 1, 2017, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/08/01/higher-ed-mergers-are-difficult-likely-grow-popularity-speakers-say. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Lauren Russell, “Better Outcomes Without Increased Costs? Effects of Georgia’s University System Consolidations,” Economics of Education Review 68 (February 2019): 122–35, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2018.12.006; Lee Gardner, “Georgia’s Mergers Offer Lessons, and Cautions, to Other States,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, June 19, 2017, https://www.chronicle.com/article/georgias-mergers-offer-lessons-and-cautions-to-other-states/; Anthony Hennen, “Improving Student Outcomes by Consolidating the University System of Georgia,” The James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal, April 12, 2019, https://www.jamesgmartin.center/2019/04/improving-student-outcomes-by-consolidating-the-university-system-of-georgia/; Andrew Gumbel, Won’t Lose This Dream: How an Upstart Urban University Rewrote the Rules of a Broken System (New York, London: The New Press, 2020). ↑

- Although the consolidation began in 2013, the consolidated institution was officially renamed Augusta University in 2015. ↑

- The Board of Regents is a higher education governing board made up of four governor appointees who serve a seven-year term. It is comprised of 19 members, five appointed from the state-at-large, and 14 that represent each of the state’s congressional districts. The Board of Regents is led by a chancellor who is elected and serves as the chief executive and administrator. ↑

- University System of Georgia Board of Regents, “Semester Enrollment Report,” 2011, https://www.usg.edu/research/assets/research/documents/enrollment_reports/fall2011.pdf. ↑

- University System of Georgia Board of Regents, “Degrees Conferred Report FY2011,” 2011, https://www.usg.edu/research/assets/research/documents/deg_conferred/deg_conferred11.pdf. ↑

- University System of Georgia “Semester Enrollment Report Fall 2011,” https://www.usg.edu/research/assets/research/documents/enrollment_reports/fall2011.pdf. ↑

- Elizabeth Baylor, “Closed Doors: Black and Latino Students Are Excluded from Top Public Universities,” Center for American Progress, October 13, 2016, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education-postsecondary/reports/2016/10/13/145098/closed-doors-black-and-latino-students-are-excluded-from-top-public-universities/. ↑

- Laura Diamond, “Concern Over Enrollment Drop at Georgia Colleges,” The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, October 9, 2012, https://www.ajc.com/news/local/concern-over-enrollment-drop-georgia-colleges/8d75ajltSLgkmdweIhlksL/. ↑

- Elliot Brack, “Georgia Falling Behind Funding Higher Education,” Like the Dew, May 5, 2011, https://likethedew.com/2011/05/05/georgia-falling-behind-funding-higher-education/#.YKl36C2cZ0s. ↑

- Robert T. Palmer, Ryan J. Davis, and Marybeth Gasman, “A Matter of Diversity, Equity, and Necessity: The Tension between Maryland’s Higher Education System and Its Historically Black Colleges and Universities over the Office of Civil Rights Agreement,” The Journal of Negro Education 80, no. 2 (2011): 121–33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41341115. ↑

- Crystal Gafford Muhammad, “Mississippi Higher Education Desegregation and the Interest Convergence Principle: A CRT Analysis of the ‘Ayers Settlement,’” Race Ethnicity and Education 12, no. 3 (September 24, 2009): 319–36, https://doi.org/10.1080/13613320903178279. ↑

- University System of Georgia, “Campuses Complete New Student Residency Verification,” Communications, August 11, 2010, https://www.usg.edu/news/release/campuses_complete_new_student_residency_verification. ↑

- University System of Georgia, “Regents Adopt New Policies on Undocumented Students,” Communications, October 13, 2010, https://www.usg.edu/news/release/regents_adopt_new_policies_on_undocumented_students. ↑

- Christina Maxouris, “Undocumented Students Sue USG for Banning Them From Georgia’s Top Universities,” The Signal, September 20, 2016, https://georgiastatesignal.com/undocumented-students-sue-usg-banning-georgias-top-universities/. ↑

- See University System of Georgia, “Serving Our Students and State,” Campus Consolidations, 2011, https://www.usg.edu/consolidation/; and University System of Georgia, “Campus Consolidation News,” Campus Consolidations, 2021, https://www.usg.edu/consolidation/news ↑

- For example, in 2015 the University of Maine System had a plan to consolidate and centralize budgeting, academic programming, and staff work, as in 2014 six of the seven campuses operated in a red zone. See Ry Rivard, “Maine Central Planning,” Inside Higher Ed, January 27, 2015, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/01/27/maine-system-looks-further-centralize-its-staff-budget-and-academic-programs. The reason for this move was simple; as Chancellor James Page stated, “Maine can no longer afford the system we have now. Maine cannot afford a system weighed down by far too much administration.” See Noel K. Gallagher, “UMaine System to Consolidate Administration, Keep 7 Campuses and Presidents,” Portland Press Herald, January 26, 2015, , https://www.pressherald.com/2015/01/26/usm-gets-80-applicants-for-presidency/. The system was faced with tight budgets and declining enrollment. ↑

- University System of Georgia, “Regents Approve Principles for Consolidation of Institutions,” Communications, November 8, 2011, https://www.usg.edu/news/release/regents_approve_principles_for_consolidation_of_institutions. ↑

- Anthony Hennen, “Improving Student Outcomes by Consolidating the University System of Georgia,” The James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal, April 12, 2019, https://www.jamesgmartin.center/2019/04/improving-student-outcomes-by-consolidating-the-university-system-of-georgia/; Andrew Gumbel, Won’t Lose This Dream: How an Upstart Urban University Rewrote the Rules of a Broken System (New York, London: The New Press, 2020). ↑

- Andrew Gumbel, Won’t Lose This Dream: How an Upstart Urban University Rewrote the Rules of a Broken System (New York, London: The New Press, 2020) 215. ↑

- University System of Georgia, “Regents Approve Principles for Consolidation of Institutions,” Communications, November 8, 2011, https://www.usg.edu/news/release/regents_approve_principles_for_consolidation_of_institutions. ↑

- Tim Renick, Interview by Sosanya Jones, February 22, 2021. ↑

- Jon Gargis, “SPSU Students Rally Against Proposed Merger with KSU [Video],” Patch, November 5, 2013, https://patch.com/georgia/kennesaw/southern-poly-students-rally-to-save-spsu-video-kennesaw. ↑

- The most prominent rumor regarding the merger between Albany State and Darton College was that the state was seeking to phase out HBCUs throughout the state/ See Jamal Eric Watson, “Controversy Surrounds Push for Albany, Darton Merger,” Diverse Issues In Higher Education, November 9, 2015, https://diverseeducation.com/article/78809/. ↑

- Mark Becker (current GSU president who will be exiting next year), Interview by Sosanya Jones, March 22, 2021. “We had a year to plan it out, there was nothing major. Student government and faculty had to work out representation and use a representation model that was consistent with each other. But all those things are working as they were designed. Faculty was straight forward. Deficit was eliminated (no duplication of admin services, we were able to eliminate the deficit).” ↑

- University System of Georgia, “Serving Our Students and State,” Campus Consolidations, 2011, https://www.usg.edu/consolidation/. ↑

- We define stakeholders as persons with affiliation to the campus- students, faculty, staff, and alumni. ↑

- Ry Rivard, “Merging Into Controversy,” Inside Higher Ed, November 6, 2013, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2013/11/06/secret-merger-now-public-meets-opposition-georgia; Rick DeSantis, “Ga. Regents Approve Merger of Southern Polytechnic State and Kennesaw State,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, November 12, 2013, https://www.chronicle.com/blogs/ticker/ga-regents-approve-merger-of-southern-polytechnic-state-and-kennesaw-state?cid2=gen_login_refresh&cid=gen_sign_in&cid2=gen_login_refresh; WALB Staff, “Students Speak Out About ASU Mission Protest,” WALB News 10, March 11, 2016, https://www.walb.com/story/31447332/students-protest-asu-status/. ↑

- David Pluviose, “Georgia HBCU Consolidation Bill May Be Reintroduced,” Diverse Issues In Higher Education, July 8, 2019, sec. Current News, News, https://diverseeducation.com/article/149010/. ; Jarett Carter, “Benefits of College Mergers Don’t Always Add Up,” Higher Ed Dive, August 1, 2016, https://www.highereddive.com/news/benefits-of-college-mergers-dont-always-add-up/423561/. ↑

- Marion Ross Frederick, Interview with Sosanya Jones, March 29, 2021. ↑

- Lauren Russell, “Better Outcomes Without Increased Costs? Effects of Georgia’s University System Consolidations,” Economics of Education Review 68 (February 2019): 122–35, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2018.12.006; Paul Fain, “Major Mergers in Georgia,” Inside Higher Ed, January 6, 2012, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2012/01/06/georgia-university-system-proposes-consolidation-8-campuses. ↑

- University System of Georgia, “Regents Approve Principles for Consolidation of Institutions,” Communications, November 8, 2011, https://www.usg.edu/news/release/regents_approve_principles_for_consolidation_of_institutions. ↑

- Sophie Quinton, “Merging Colleges to Cut Costs and Still Boost Graduation Rates,” PEW Stateline, March 29, 2017, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2017/03/29/merging-colleges-to-cut-costs-and-still-boost-graduation-rates. ↑

- Lauren Russell, “Short-Term Impacts of College Consolidations: Evidence from the University System of Georgia,” Massachusetts Institute of Technology, November 28, 2018, http://economics.mit.edu/files/16468. ↑

- Lauren Russell, “Better Outcomes Without Increased Costs? Effects of Georgia’s University System Consolidations,” Economics of Education Review 68 (February 2019): 122–35, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2018.12.006. ↑

-

Georgia State University, “Georgia State’s Perimeter College Ranks Among Nation’s Best for Student Success,” January 16, 2020, https://news.gsu.edu/2020/01/16/georgia-states-perimeter-college-ranks-among-nations-best-for-student-success/.↑

-

We thank Dr. Tim Renick for providing us this information on the student success gains at Georgia State-Perimeter.↑

- University System of Georgia Board of Regents “University System of Georgia Degrees and Awards Conferred Fiscal Year 2020”. https://www.usg.edu/research/assets/research/documents/deg_conferred/srpt602_p_rpa_fy2020.pdf ↑

- University System of Georgia Board of Regents “Semester Enrollment Report-Fall 2016,” https://www.usg.edu/assets/usg/docs/news_files/BOR-USG_Fall_2016_Enrollment.pdf. ↑

- University System of Georgia Board of Regents “Semester Enrollment Report-Fall 2020,”https://www.usg.edu/research/assets/research/documents/enrollment_reports/SER_Fall_2020_Update2.pdf. ↑

- University System of Georgia Board of Regents “Semester Enrollment Report-Fall 2016,” “Semester Enrollment Report-Fall 2017,” https://www.usg.edu/research/assets/research/documents/enrollment_reports/SER_Fall_2017_Final.pdf. ↑

- University System of Georgia Board of Regents “Semester Enrollment Report-Fall 2020,”https://www.usg.edu/research/assets/research/documents/enrollment_reports/SER_Fall_2020_Update2.pdf. ↑

- Lauren Russell, “Better Outcomes Without Increased Costs? Effects of Georgia’s University System Consolidations,” Economics of Education Review 68 (February 2019): 122–35, p.17, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2018.12.006. ↑

- University System of Georgia “Semester Enrollment Report Fall 2020,” https://www.usg.edu/research/assets/research/documents/enrollment_reports/SER_Fall_2020_Update2.pdf. ↑

- Mark Becker, interview with Sosanya Jones, March 22, 2021. ↑

- Georgia State University, “2015 Status Report Georgia State University: Complete College Georgia,” Status Report, 2015, https://success.gsu.edu/download/2015-status-report-georgia-state-university-complete-college-georgia/?wpdmdl=6470560&refresh=60bce4299980b1622991913. ↑

- Andrew Gumbel, Won’t Lose This Dream: How an Upstart Urban University Rewrote the Rules of a Broken System (New York, London: The New Press, 2020) 215. ↑