A Texas Merger

The Creation of University of Texas Rio Grande Valley

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following people for speaking with us about both the events around the creation of the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley as well as higher education more generally in the State of Texas:

- Francisco G. Cigarroa, M.D., Professor of Surgery and Director of the Transplant Center, Carlos and Malú Alvarez Distinguished University Chair, and Ashbel Smith Professorship in Surgery, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio

- Steven Reed Collins, former Associate Vice Chancellor for Governmental Relations for the University of Texas System and Special Counsel to the Office of the General Counsel

- Julieta V. Garcia, Professor, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, former President of Texas Southmost College, University of Texas at Brownsville and Texas Southmost College, and University of Texas at Brownsville

- Harrison Keller, Commissioner of Higher Education for the State of Texas

- David Oliveira, Partner, Roerig, Oliveira & Fisher, former member of TSC Board of Trustees for 18 years, including four as Chair

Introduction

Background

In December of 2012 administrators for the University of Texas (UT) System[1] announced a proposed merger of University of Texas-Brownsville and the University of Texas-Pan American “with an eye toward securing increased state funds and potentially building a medical school.”[2] Both increased funding and the medical school were seen as important equity issues, given South Texas’s low per capita incomes and predominantly Hispanic population.

The status of University of Texas at Brownsville (UTB) and University of Texas Pan American (UTPA) within the UT system, along with the relationship between UT Brownsville and the local Brownsville community college, Texas Southmost College (TSC), played a large role in the proposed merger, and the history of these relationships is key in understanding the motivation for and impact of the merger. While most of the mergers conducted in other states have been framed in terms of cost cutting and generating economies of scale, according to public documents “the merger of UT-Brownsville and UT-Pan American, if approved, would be a move in a slightly different direction. While the combination of the institutions would save as much as $6 million in administrative costs, system administrators say their merger is focused on growing the institutions and, as a result, gaining political and academic leverage for greater investment.”[3] A motivating factor, however, was a deteriorating relationship and failed renegotiation of the 1991 agreement between UT Brownsville and Texas Southmost College that put 20 years of cooperation between the institutions and the students they served at risk.[4]

After reviewing the history and motivation for the merger, we will explore available information on the merger’s impact on students and other constituencies. The merger accomplished many of its stated goals, but there were also costs from the dissolution of the 20-year relationship between UTB and TSC. How the merger came about and its impact on students suggests several lessons for other systems considering mergers as a means of improving educational outcomes.

The history of TSC, UTB, UTPA, and University of Texas Rio Grande Valley (UTRGV) is embedded in the history of higher education more generally in Texas, and in particular its long history of discrimination against Hispanics, especially Mexican Americans, as well as other underrepresented groups, since the Texas higher education system was founded in 1876. Few of these colleges and universities were located in regions with high Mexican American populations—particularly along the border with Mexico—and these institutions were underfunded compared to those in other regions of the state. In addition, admissions policies also contributed to significant underrepresentation of Hispanics at public colleges and universities across the state. This issue of unequal post-secondary higher education access and success in Texas started receiving increased attention in the early 1970s, as it did across the country, in part in response to Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Equal educational opportunity in Texas has been on the state’s agenda since then.[5]

The merger creating University of Texas Rio Grande Valley is part of this many-decades-long history of committing to improving educational opportunities for Mexican Americans in the state of Texas.

In some cases, focus on these issues came from outside the state or from actions by advocacy groups within the state. In 1970, for example, the NAACP filed a case against the US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare for failing to eliminate racial discrimination in higher education.[6] This led to a US Department of Education Office of Civil Rights (OCR) investigation of the state of Texas, and Texas adopting the Texas Plan in 1983 in response.[7] Several additional five-year plans followed. In 1987, the Mexican American Legal Defense Fund filed a class action lawsuit against the state of Texas, claiming the state discriminated against Mexican Americans living along the South Texas border by not supporting higher education opportunities in the region that were available in other parts of the state. This contributed to the South Texas Border Initiative (1993), a set of legislative initiatives designed to improve higher educational opportunities along the border.[8] Between 1991 and 2013, the region’s share of state funding for public universities increased closer to its share of the state’s population, and educational opportunities for the predominantly Mexican American population improved, including a significant increase in access to graduate programs.[9] Over time, state policy makers increasingly focused not only on the equity issues around access to quality higher education public institutions, but realized that the state’s economic success was intricately entwined with improving educational attainment more broadly across the state and across demographic groups, given demographic projections.[10]

The merger creating University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, or UTRGV, is part of this many-decades-long history of committing to improving educational opportunities for Mexican Americans in the state of Texas.

History Leading Up to the Merger

In May of 2013, “the Texas Legislature overwhelmingly passed Senate Bill 24, authorizing the creation of a new university in South Texas and a medical school, making it eligible to tap the multibillion-dollar Permanent University Fund, comprised of oil and gas revenue.”[11] The legislature approved this move and the bill was signed by Governor Rick Perry in July of 2013 authorizing the merger of University of Texas at Brownsville and University of Texas Pan American into the new university. Five months later in December of 2013, it was announced that the name for the merged university would be University of Texas-Rio Grande Valley, or UTRGV. Merged classes were expected to begin in 2015, leaving time for the relationship between TSC and UTB to be sorted out. The addition of a medical school in south Texas was something the system and the community had been working on for several decades and the merger finally set this in motion.[12]

The System Environment Prior to the Consolidation

UT at Brownsville and UT Pan American had a long history together preceding the merger, but the relationship with the Brownsville community college, Texas Southmost College (TSC) is also a significant and important component of the story. TSC and UT-PA both started as two-year institutions in the 1920s. Eventually UT-PA became a four-year institution in 1951, and ultimately a university. What eventually became the University of Texas at Brownsville was created by the precursor of UT Pan American—Pan American University—in 1973. That year, Texas Southmost College, a two-year college, formed a partnership with Pan American University. That led to Pan-American University establishing a satellite location, an upper-level baccalaureate university in Brownsville, named Pan American University at Brownsville. Texas Southmost College offered an associate’s degree, and Pan American University at Brownsville offered a bachelor’s degree, with seamless transfer between the two institutions, which were co-located in the facilities officially owned by TSC.[13] This allowed students in the Brownsville area to go on to a four-year degree without having to commute over an hour away to UTPA in Edinburg, Texas.[14]

In 1989, Pan American University joined the University of Texas System, which led to the creation of the University of Texas Pan-American at Brownsville (UTPA-B).[15] In 1991 the University of Texas Pan-American at Brownsville sought its own recognition within the system and became the University of Texas at Brownsville (UTB), the 15th institution within the UT system.[16] These institutions, with their predominately Hispanic student bodies, were brought into the UT system in large part for political reasons. By joining the UT system, they gained access to additional support from the system, while the system increased its overall share of Hispanic students. This was part of Texas’ response to the contemporaneous legal action and advocacy of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund, which had argued that Texas wasn’t spending enough on higher education in South Texas, discriminating against the predominately Hispanic population.[17] At that time, an official agreement was reached between Texas Southmost College and UTB, approved by the TSC Board and the UT system Board of Regents. It included a transfer pathways program, allowing for students to start at TSC and then complete their degree at UTB. The agreement called for open admissions (for both first years and transfers), making transfer truly seamless. Starting in 1991, TSC and UTB shared a president, Juliet Garcia, in recognition of the close, integrated nature of the two institutions, embodied in the agreement known as the UTB/TSC Agreement.[18] Julieta Garcia was the president of UTB and TSC from 1991 to 2011, and was the first female Mexican American president of a college or university in the United States.[19]

The relationship between TSC and UTB that was negotiated in 1991 was itself unique and responsive to the challenges that the community was facing at that time. It gave students earning an associate’s degree the opportunity for seamless transfer to the bachelor’s program, increasing educational opportunity in an underserved and financially challenged community.[20]

The governance structures of TSC and UTB were complicated, but important to the history of their relationship that ultimately unraveled in 2010. The community college had its own board of elected members from the local community, with its own taxing authority and ability to issue bonds to raise funds for capital projects. UTB, however, was under the authority of the Board of Regents of the University of Texas System. The former was regional, while the later was at the state level. From 1991, the two institutions shared a president and functioned smoothly as two institutions but working cooperatively. It was an innovative structure that allowed for seamless transfer of community college students to a four-year degree program. And, it allowed Brownsville students to attain a bachelor’s degree without having to commute over an hour to the closest alternative or worry about transferring credits. This complicated structure, with two boards, was in contrast to UTPA—when Pan American University was brought into the UT System, in 1989, its separate board was dissolved.

UTB and TSC served a predominately Hispanic population in one of the lowest income regions in Texas. This was one of the motivations for moving both the Pan American and Brownsville institutions into the UT system in 1989 and 1991, giving them access to greater support and changing the overall demographics of the UT system.

In the UTB/TSC relationship, UTB became the operating entity. Most operations were combined, including academics, although all employees officially were employed by UTB while teaching in different programs. The TSC Board contracted with the UT system to deliver all academic programs and services. TSC’s campus and facilities were used, and TSC paid UTB for the delivery of programs, including by transferring tuition, fees, and state appropriations. UTB in turn paid rent to TSC. The TSC Board remained intact and retained local taxing authority and management of the assets of the college and monitored the agreement with UTB.

UTB and TSC served a predominately Hispanic population in one of the lowest income regions in Texas. This was one of the motivations for moving both the Pan American and Brownsville institutions into the UT system in 1989 and 1991, giving them access to greater support and changing the overall demographics of the UT system. At the same time while this change gave access to some new resources, UTB and UTPA did not have access to the same resources (especially the Permanent University Fund) as other UT institutions because they were excluded by state law as pre-existing institutions. In addition, there was some resentment by local politicians that the local tax base in this poor region was supporting an institution—UTB—with a statewide service area.

The official educational partnership between TSC and UTB ended in 2010/11. The University of Texas System stated that “while we were hoping to forge a new relationship that would propel the UT System and TSC into the future as partners, we have come to the conclusion that the current working situation is untenable, and therefore, the UT System will concentrate on advancing higher education in South Texas and at The University of Texas at Brownsville (UTB) without a partnership with TSC.”[21] However, the agreement included a required four year transition period. Both the complicated financial arrangements between TSC and UTB and a power struggle between the two boards, with perhaps different visions for the future, contributed to the dissolution of the partnership. With an election of new board members to TSC in 2011, the board wanted to reestablish local control and cut off the relationship with the UT system. The UT system had been looking to renegotiate the 1991 agreement, presumably to increase control over the entire four-year program, and when the TSC board failed to renegotiate, the UT system declared the agreement to be at an end.[22]

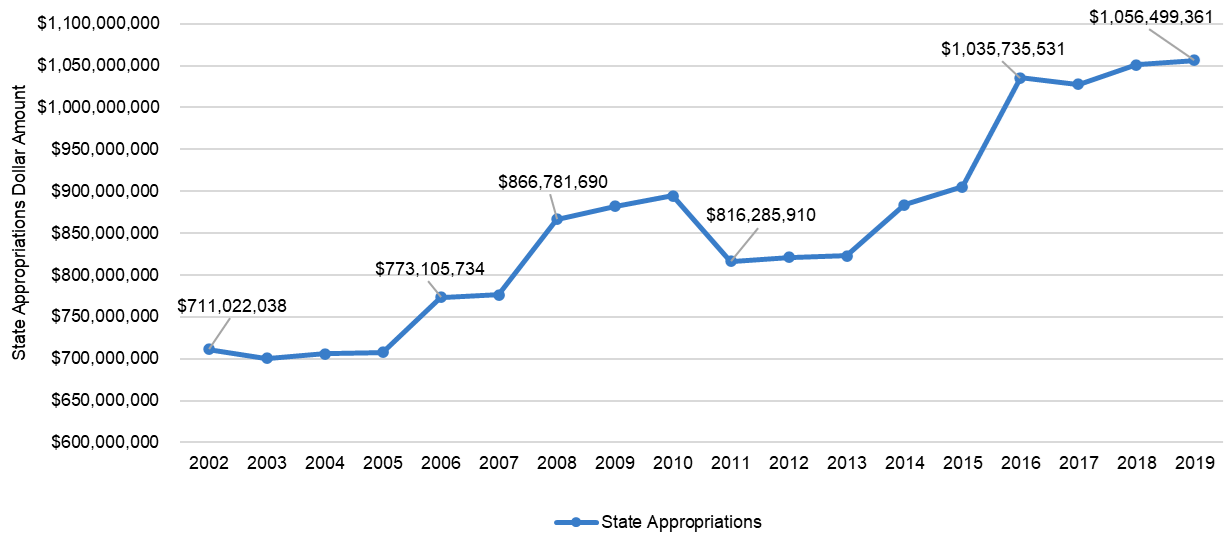

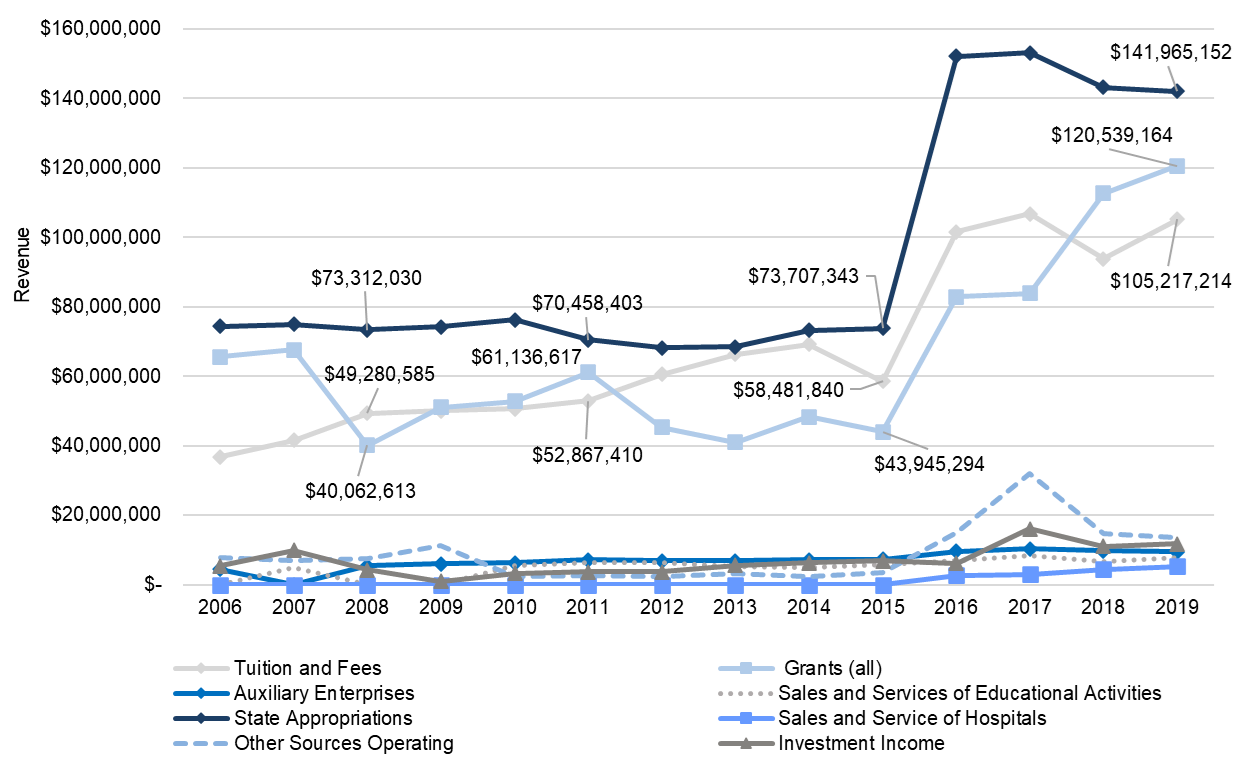

Long standing fiscal disputes between TSC and UTB played a role in the dissolution. TSC trustees complained of unpaid rent, resulting from state funding shortfalls that affected the UT system—in part a result of the 2008 financial crisis (see Figure 1, which shows the impact of the financial crisis on state appropriations which didn’t recover for roughly five years). The institutions were asked to resolve the dispute by 2011. A UTB/TSC task force that was formed to suggest solutions recommended merging the two institutions into one, under the UT system. The TSC board rejected the recommendation, and the UT regents voted to end the partnership, as did the TSC trustees, by a four to three vote.[23] While not explicitly stated, the majority of the TSC trustees viewed a new agreement with the UT system as a hostile takeover of TSC.

Figure 1: State appropriation trends at the academic institutions within the UT Systems from 2002 – 2019[24]

This left UT Brownsville in a particularly precarious position, in that TSC was the source of transfer students and tuition revenue. Also, TSC owned the facilities and had access to bond financing that UTB did not. At the same time, UTB, as well as UTPA, did not have access to funds through the Permanent University Fund (PUF) that other UT system institutions had.

This also, of course, affected students. Up until 2011, UTB practiced open admissions and students could seamlessly transfer from TSC. After the dissolution, this seamless transfer pathway also ended, and the entering class in 2013 at UTB was subject to new admissions criteria, making it more difficult to transfer into the baccalaureate program.

Motivation for the Merger of UTB and UTPA

The dissolution of the agreement between UTB and TSC was a motivating factor in the merger of UTB and UTPA. After the relationship with TSC ended, UTB became unsustainable financially, putting large numbers of students—predominantly Hispanic and low-income—at risk of not being able to continue their education as planned. This motivated the Board of Regents of the UT system to propose the merger of UTB and UTPA, which offered additional benefits to both institutions.

Dr. Francisco Cigarroa, chancellor of the University of Texas System at the time, was born and raised in South Texas, and the Chair of the Board of Regents, Gene Powell, was also from the Rio Grande Valley. Both played a significant role in the legislative approval needed to create UTRGV in 2013. Then-Governor Rick Perry approved of the merger, and with the UT Regents supported by Perry, and a predominantly Republican legislature, the merger was quickly approved.[25]

In ending the relationship with TSC, UTB became unsustainable financially, putting large numbers of students— predominantly Hispanic and low-income—at risk of not being able to continue their education as planned.

Prior to merging, the two UT institutions were each relatively small for Texas institutions, with limited research activity.[26] When they each individually became part of the UT system around 1990, they were ineligible for some sources of state funding, including importantly the Permanent University Fund, or PUF. The institutions were also unlikely to be able to support the founding of a medical school, long an aspiration for the region, because of their size and limited access to resources. The region was significantly underserved by the medical system, and a medical school was seen as a way to in part address this issue.[27] Merging the institutions and creating a new university meant the new institution would have access to the PUF, solving the financial challenges facing UTB.[28]

The Permanent University Fund was created by the Texas Constitution (Article 7, Section 18.)[29] The PUF is essentially an endowment which generates annual earnings, which fund the Available University Fund (AUF), available to support institutions within the UT system and the Texas A&M system.[30] With the exception of UT Austin, TAMU College Station, and Prairie View, institutions do not receive a direct distribution from the AUF. The institutions benefit instead because the regents issue bonds for capital construction and similar purposes, using the PUF as collateral, providing for low interest rates. The debt service is also paid from the AUF, essentially covering the capital costs of the institutions.[31]

Part of the motivation for the merger was that UTPA and UTB served one of the most under-resourced parts of the state. In addition, the population was predominantly Hispanic, and the Board of Regents and state politicians were facing criticism (and litigation) around issues of equitable access to higher education.

Under a constitutional amendment passed in 1984,[32] only new institutions can receive access to the PUF, and it takes a two-thirds vote of each house in the state legislature to create a new institution. Pre-existing institutions not listed in the 1984 PUF amendment do not benefit from the PUF. Thus, UTPA and UTB did not have access to PUF funding when they joined the UT System since they were not new institutions created by the state legislature. Consequently, the predominately Hispanic institutions within the UT system, while eligible for other funding, did not have access to the significant resources of the PUF, which were benefiting more elite institutions. However, merging created a new institution, UTRGV, which then gained access to these funds.

The political support for the creation of UTRGV, giving it access to PUF resources, was complicated. It meant that other UT institutions would have to share the PUF funds with a new institution, potentially aligning members of the Board of Regents and/or the legislature against the move. Part of the motivation was that UTPA and UTB served one of the most under-resourced parts of the state. In addition, the population was predominantly Hispanic, and the Board of Regents and state politicians were facing criticism (and litigation) around issues of equitable access to higher education. And the dissolution of the relationship between TSC and UTB put UTB at risk of not surviving financially, significantly disadvantaging Hispanic students in South Texas, creating some urgency to find a solution. It was also the case that UT Austin wanted to create a medical school at the time and needed approval. The PUF was also doing reasonably well, and there was an understanding that resources for UT Austin would be maintained, through a small increase in allocation.[33]

In the end, it was in the political interests of members of the legislature of south Texas and Austin to move forward on both initiatives. These aligned interests helped with gaining approval of the merger more broadly.[34]

Additional Considerations

Unlike some mergers and consolidations that are focused on cutting costs, the motivation for merging UT Brownsville and UT Pan American along with the regional academic health center was quite explicitly targeted at increasing the resources available to both institutions (and their local communities) and also making possible the opening of a medical school in South Texas.

A Medical School

To make the medical school a possibility, there needed to be a university that had the potential to grow into a major research university. Neither UT Brownsville nor UT Pan American was designated as an “emerging research university” by the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board or had hopes of becoming one any time in the near future. By merging, they gained the scale necessary to be eligible—a requirement to gain access to additional state incentive funds to support growth into a major research institution. At the time, it was hoped that this would facilitate transitioning the regional academic health center into a medical school.[35] UTRGV has not yet qualified as a major research institution but was nonetheless able to proceed with establishing a medical school.

When the merger was announced in December 2012,[36] it was estimated that creating the medical school would require $100 million in resources over the coming decade. At the same time, the merger of the two UT institutions would lead to about $6 million in cost savings by eliminating redundancies, although this was not a major motivating factor.[37]

The idea that a medical school should be associated with a large research university was also clear in the plan. By having the medical school and research university integrated, both are more competitive in terms of recruiting faculty and students, as well as research dollars.

The presidents of the two UT institutions, Julieta Garcia of UT Brownsville and Robert Nelsen of UT Pan American, endorsed the proposal. With consolidation being focused on increased access to state resources and improved medical care in the region, endorsing the merger was perhaps easier than might otherwise have been the case. While neither president could count on becoming president of the merged, and officially new institution, and neither did succeed to that role in the end, they nonetheless endorsed the proposal. Since both of their institutions and communities would benefit, this was easier than in some other mergers in which one of the partners is expected to lose more than it gains.

In April of 2014, the UT Board of Regents announced Guy Bailey as the sole finalist to become UTRGV’s inaugural president.[38] He had significant experience running large research institutions, including having been provost of UT San Antonio (UTSA) as well as at Texas Tech. While at Texas Tech, the university’s research expenditures grew about 170 percent. While at UTSA, the university became an “emerging research university” and external research funding doubled. In selecting Bailey, with his significant major research university experience, the regents signaled their aspirations for the new university to become a major research institution.[39]

Julieta Garcia became the executive director of the University of Texas Americas Institute. UTPA President Robert Nelson resigned and was given tenure and a one-year appointment, working within the UT system, but eventually left to become president of California State University, Sacramento.[40]

The Consolidation Process: Challenges, Anticipated and Unanticipated

Before UTB and UTPA could be merged, UTB/TSC first had to be divided up.[41] This included faculty, buildings, and even the mascot (the scorpion went to TSC). The 20 years of close ties made the divorce especially complicated. For example, state monies had been used to restore TSC owned buildings, built with local taxpayer monies, making ownership unclear. On the other hand, TSC invested local resources in facilities it would not have built without the relationship with UTB, that served the four-year program more than the community college component. This included athletics facilities, an art center, and a student union.[42]

UTB/TSC shared accreditation as one entity, convenient during the 20-year relationship. Accreditation was due to end during 2015, which set a deadline for finalizing the split. It also meant that each institution had to obtain its own reaccreditation by that deadline.

TSC received separate accreditation from UTB through the SACSCOC (Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges) in December 2015.[43] UTRGV initially relied on UTPA’s accreditation.

There were challenges for students, as the close relationship with TSC and UTB was dissolved and UTRGV was created, which took some time to sort out. Upper-level students of course became UTRGV students by default. Students in the first two years at UTB/TSC had to decide which institution to affiliate with. In some cases, it was determined by program. But, in other cases, students had to make a choice.

When UTB and UTPA officially became UTRGV, there were some initial complications around a variety of issues, and on December 6, 2016, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC) notified UTRGV that it was being placed on probation for a year.[44] SACSCOC cited 10 areas of concern.[45] These included not complying with financial aid audits and relying on other institutions for a variety of courses rather than supplying instruction itself for degrees offered. There were also early complications around recognizing course credits from UTB and UTPA, given changes in course numbering and names. This was really a transitional problem which had been anticipated, but not adequately addressed ex ante. With time, these issues and others were resolved. The new president’s message to the UTRGV community at the time confirmed that UTRGV remained accredited and that the issues were related to the timing of the evolution of UTRGV. In 2018 UTRGV was removed from probation.

There was significant disruption to faculty and staff at TSC, UTB, and UTPA when the TSC/UTB agreement was dissolved and UTB and UTPA merged.[46] Not all faculty and staff retained their jobs, including faculty with tenure. At UTB and UTPA, faculty with tenure or on the tenure track had to reapply, with a large share, but not all, automatically transitioned to similar positions in UTRGV.[47] In the fall of 2010, the combined faculty of UTB and UTPA was 1,318. In the fall of 2016, the faculty count at UTRGV was 1,218. The share of tenured or tenure track remained approximately constant at about 50 percent.[48]

The decline in faculty at TSC was much more precipitous over this period. It fell from 521 (92 full time) in 2010 to 155 over this period, with 55.5 percent full time.[49]

Outcomes

By improving access to resources and transitioning to a major research institution, post-secondary educational opportunities at UTRGV for students in the region increased. The combined undergraduate enrollment at UTPA and UTB increased almost 11 percent from 21,644 in 2010 (before news of the merger) to 24,023 at UTRGV in fall 2016.[50]

By improving access to resources and transitioning to a major research institution, post-secondary educational opportunities at UTRGV for students in the region increased.

Admissions standards for the combined four-year program changed in that previously UTB practiced open admissions, accepting all transfers from TSC, which was also an open enrollment institution. The admit rate at UTRGV in 2016 was 63.9 percent, compared to 100 percent at UTB and 69.6 percent at UTPA in 2010. TSC currently has an articulation agreement with UTRGV,[51] and 34.9 percent of UTRGV graduates come with 30 semester credit hours or more from two-year colleges. But the seamless transfer of the TSC/UTB agreement no longer exists.

While students wanting to receive a bachelor’s degree can start at UTRGV or at TSC and then transfer, the end of the close relationship between TSC and UTB did have negative implications for some students beyond the automatic transfer. In the past some students would start at TSC assuming the associates degree would be their terminal degree. But, by attending an institution with other students working toward a bachelor’s, some then realized they could earn that degree as well. The close relationship not only made transfer seamless, but also changed aspirations on the part of many students.[52]

The overall impact of the merger of UTB and UTPA therefore also depended on the impact on TSC. Given the conflict between the TSC board and UT Board of Regents, it wasn’t surprising that the UT Board did not focus to any great extent on the impact on TSC. Over the same time period, 2010 – 2016, when UTRGV enrollments increased from the pre-merger levels at UTB and UTPA, enrollment at TSC declined by more than 54 percent from 11,043 to 5,062. Some of this reduction may account for growth in UTRGV enrolment, as students who previously might have started at TSC and transferred to UTB chose to start at UTRGV instead. The combined enrollment at TSC and UTB and UTPA in the fall of 2010 (32,687) was larger than the undergraduate enrollment in fall 2016 in TSC and UTRGV (29,085). We do not know, however, what would have happened if the merger had not occurred or the shorter-run impact of the changed relationship among these institutions.[53]

While the number of TSC students declined significantly over this period, beginning in 2010, the share that were full time (about 30 percent) and the share enrolled in academic programs (80 percent) versus technical programs (20 percent) remained approximately the same. When the agreement between UTB and TSC fell apart, there was discussion about having the community college focus more on job skills training. This was not reflected in an increasing share of students enrolled in technical programs. Nor did the share of dual credit in total enrollment change much.[54]

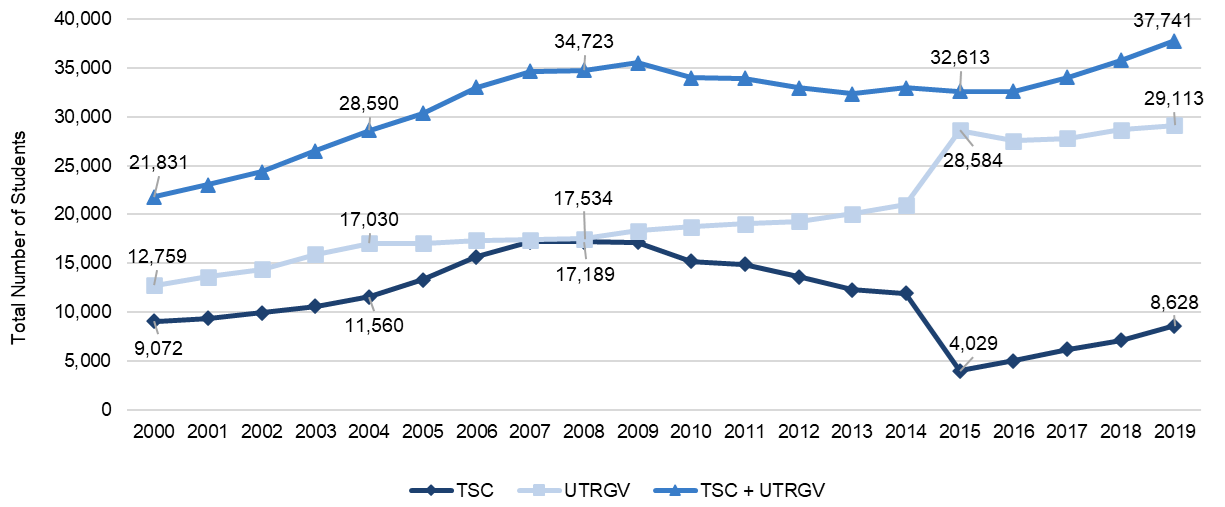

Figure 2: Total fall enrollment at TSC, UTRGV, and TSC + UTRGV from 2000 – 2019

Figure 2 reports enrolment data from IPEDS, including graduate students. The TSC line includes UTB enrolments until 2015, while the UTRGV data pre-2015 include UTPA enrolments, but not UTB. The jump in 2015 in UTRGV enrolments and drop in TSC enrolments are in part the result of reclassifying UTB enrolments from TSC to UTRGV after the merger in the IPEDs data. Looking at both the Almanac data and the IPEDS data, we do know that TSC enrolments declined by more than this as some students who would have previously enrolled in TSC and then transferred to UTB, after the merger started at UTRGV rather than counting on transferring. Looking at total enrolments, the combined enrolments recorded in IPEDs for both UTRGV and TSC do increase from 32,613 to 37,741 between 2015 and 2019, but with fewer students in TSC. This reverses declining total enrolments across all the institutions combined after the financial crisis of 2008/9 through 2015.

In initiating a strategic planning process in 2017-18, TSC talked about “still emerging from two decades of operations under UTB.”[55] Clearly, ex-post, the “agreement” was not seen as a mutually beneficial partnership. A question that is difficult to answer is whether the South Texas community, and especially its students, are better-off as a result of TSC and UTB’s inability to update their once long-standing agreement. This led to UTRGV plus a new version of TSC, now continuing to serve the region, which may have been a better outcome than an updated UTB/TSC relationship.

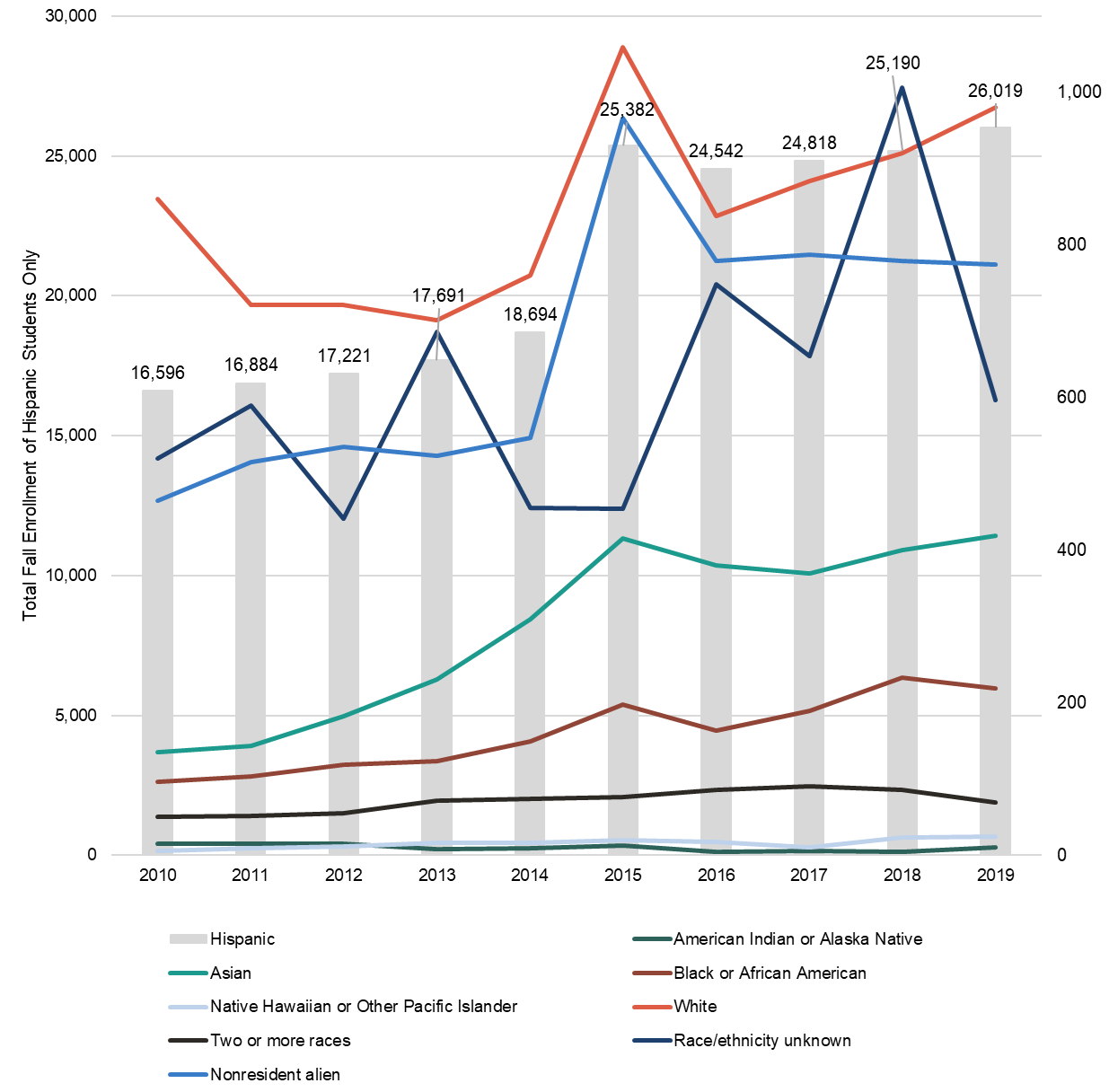

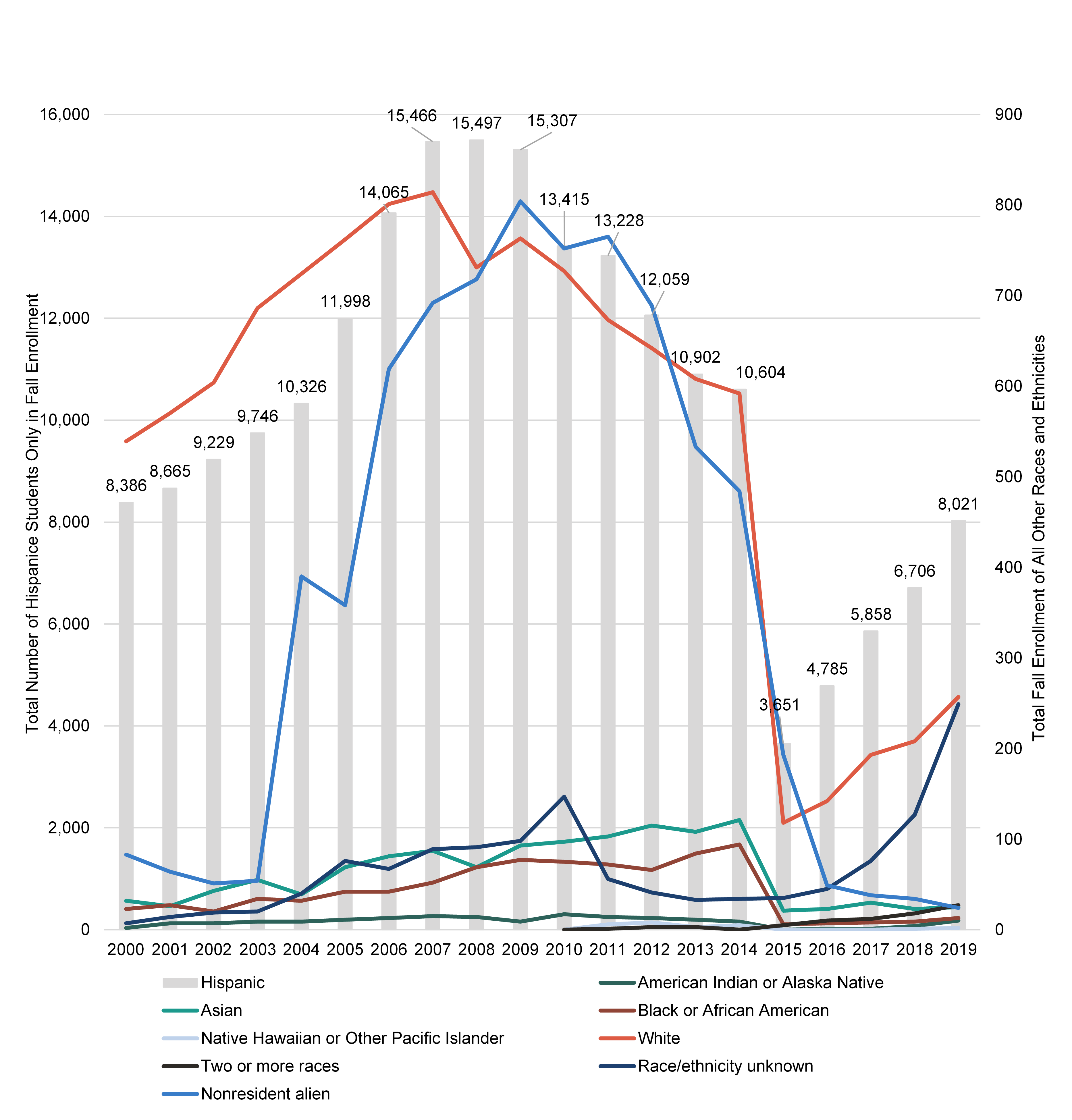

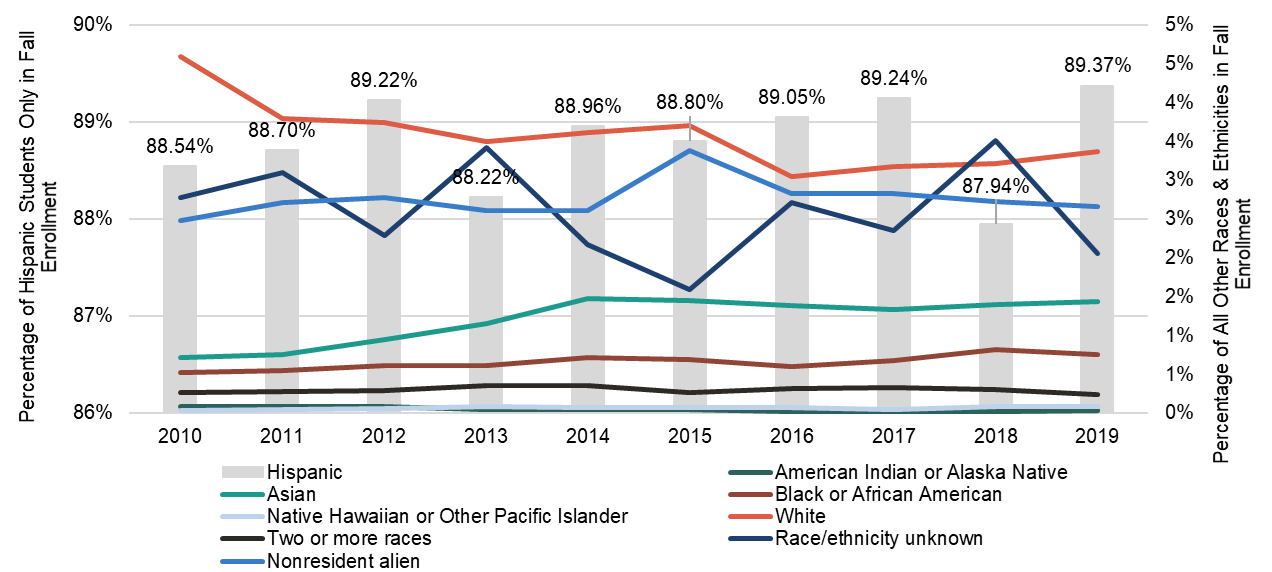

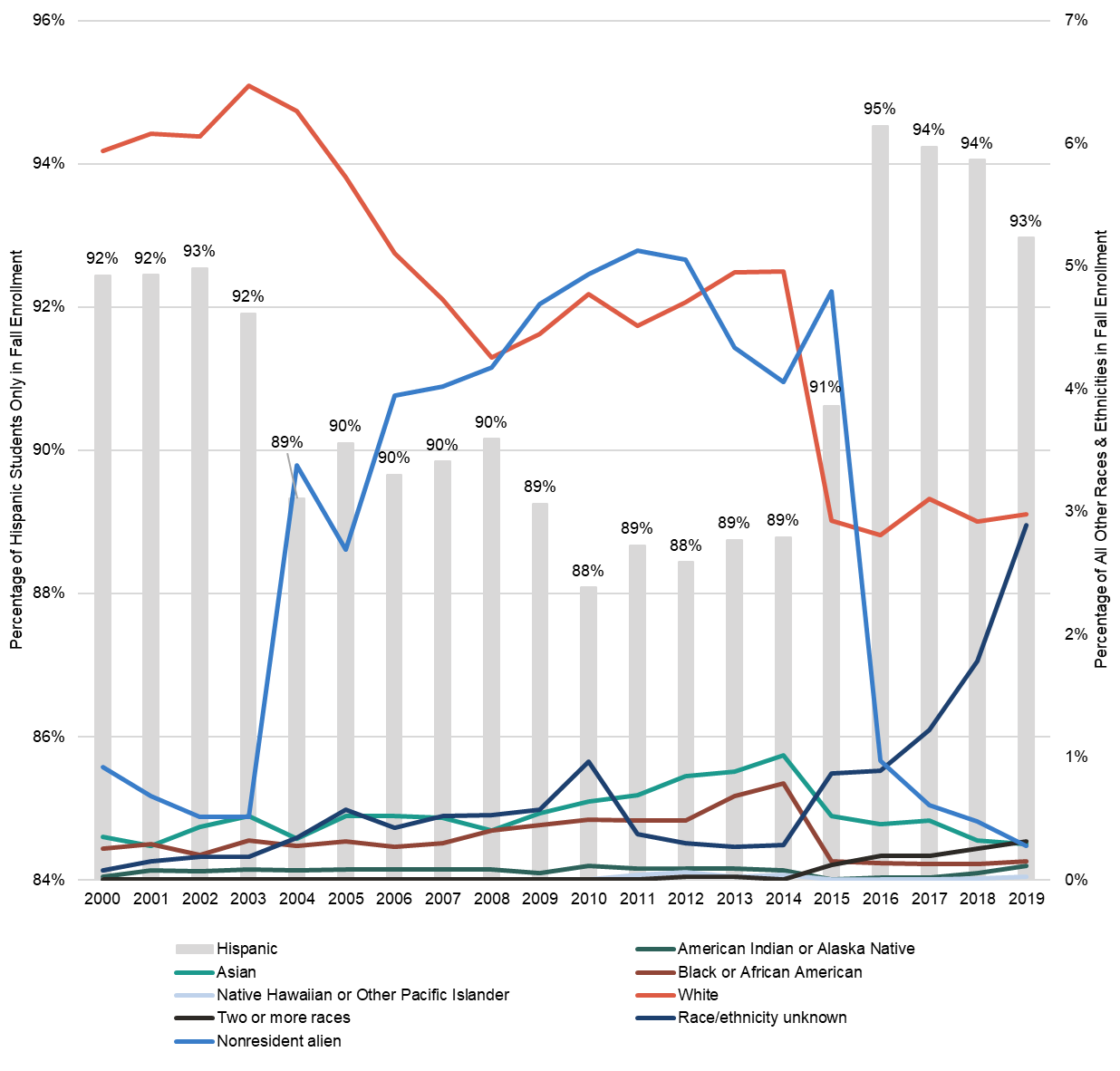

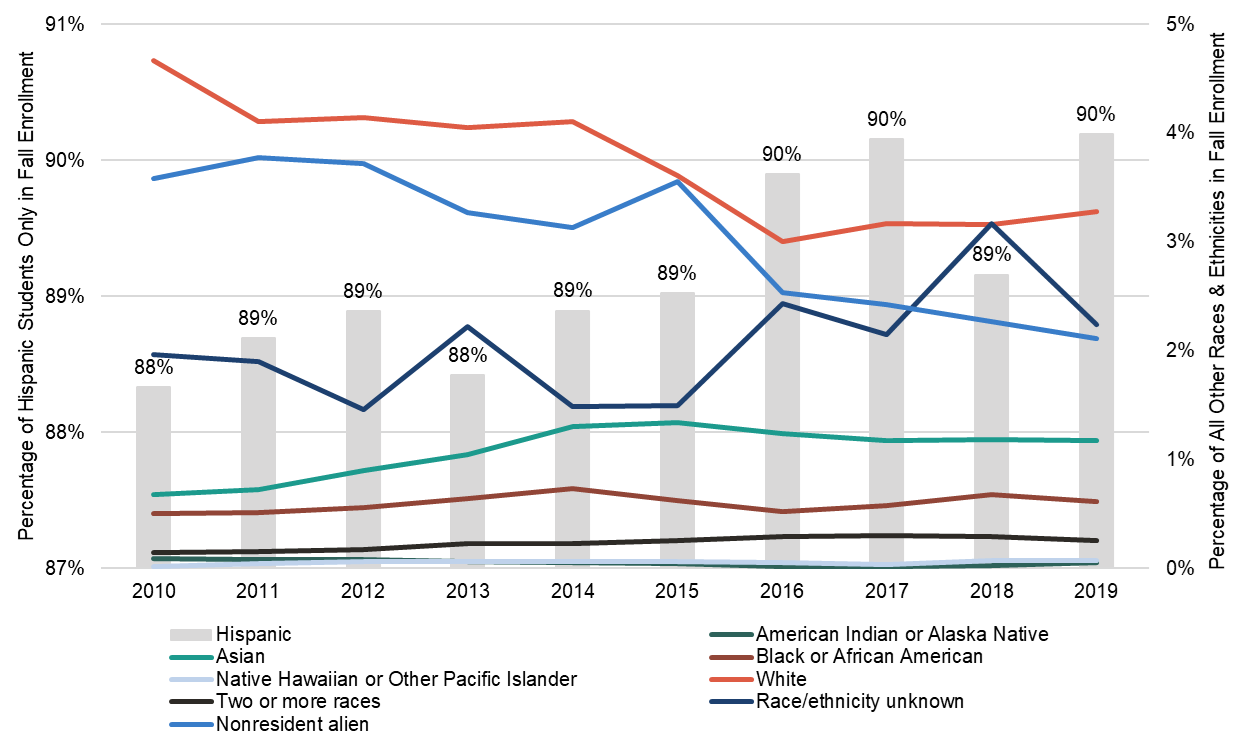

As with the total enrolment data, the IPEDS data on enrolment by race and ethnicity include UTB with the TSC data pre-merger, while these enrolments then move to UTRGV post-merger. Figures 3 (a-c) report the counts, while Figures 4 (a-c) report shares. The scale on the left of each graph reports fall enrolments of Hispanic students, while the scale on the right reports all other groups. All graphs confirm TSC, UTB, UTPA and then UTRGV are all predominately Hispanic institutions, with Hispanic students accounting for close to 90 percent of enrollments. The next largest groups are white students and non-resident aliens, but even these account for only about three to five percent of enrolments. With the creation of UTRGV, white and non-resident alien enrolments at TSC (UTB) declined, increasing the share of Hispanic students remaining at TSC from 91 percent in 2015 to 95 percent in 2016. The share of Hispanic students in the combined institutions (TSC, UTB, UTPA and UTRGV) remained at about 88 percent to 90 percent over the entire period of 2010 to 2019. The shift of white students away from TSC seems to have been reflected in an increased number of white students at UTRGV. At the same time, the total number of white students in the combined institutions increased from 2016 to 1019, but from low numbers, and over the entire decade of 2010 to 2019, the number of white students declined. Policies across Texas may explain this drop, including the Texas 10 percent plan.[56]

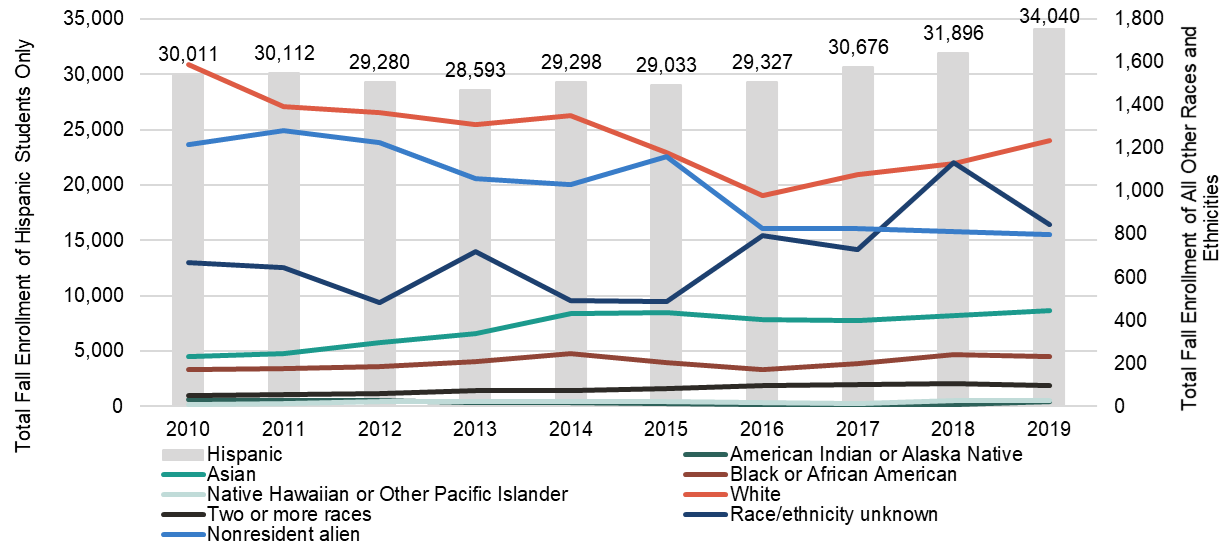

Figure 3a: Fall enrollments at UTPA (2010 – 2014) and UTRGV (2015 – 2019) pre- and post-merger. Numerical total fall enrollment population by race and ethnicity from 2010 – 2019.

Figure 3b: Fall enrollments at UTB and TSC (2000 – 2014) and TSC (2015 – 2019 represents just TSC data) pre- and post-merger. Numerical total fall enrollment by race and ethnicity from 2000 – 2019.

Figure 3c: Total fall enrollment for UTRGV and TSC combined from 2010 – 2019 by race and ethnicity.

Figure 4a: Fall enrollments by race and ethnicity as shares of total fall enrollment at UTPA (2010 – 2014) and UTRGV (2015 – 2019) pre- and post-merger.

This figure compares shares of the total fall enrollment racial and ethnic makeup.

Figure 4b: Percentage of total fall enrollment population at TSC by race and ethnicity pre- and post-merger from 2000-2019.

This figure compares shares of the total fall enrollment racial and ethnic institutional makeup (UTB and TSC data are combined from 2000 – 2014 and just TSC data is reported from 2015 – 2019)

Figure 4c: Fall enrollment by race and ethnicity as shares of the total fall enrollment at UTRGV (UTPA data from 2010 – 2014 and UTRGV data from 2015 – 2019) and TSC (UTB and TSC data combined from 2010 – 2014 and just TSC data from 2015 – 2019) combined.

This figure compares shares of the total fall enrollment racial and ethnic institutional makeup and looks at total fall enrollment racial and ethnic shares of TSC and UTRGV combined from 2010 – 2019 in an attempt to account for IPEDS data reporting discrepancies. While it is clear that both UTRGV and TSC students are predominantly Hispanic, this figure still provides an interesting perspective on fall enrollment.

Before the merger in 2010, tuition and fees at TSC, UTB, and UTPA were all very similar ($5,714, $5,498, $5,425 respectively).[57] At the time, TSC worried that its tuition was too high for some students, particularly those not seeking either an associate’s degree or bachelor’s degree, but skills training for job advancement.

After the merger and creation of UTRGV, in 2016 UTRGV’s average tuition and fees per student were $7,448, while TSC’s had declined to $3,900.[58]

Students seeking a bachelor’s degree who previously could have started at TSC may have been disadvantaged by the merger. They could of course start at TSC and transfer to UTRGV, but that process was no longer automatic.

The primary equity considerations behind the merger had to do with saving UTB and the students that it served. In addition, an added benefit was hoped-for improved access to health care, in addition to improving access to quality post-secondary education, including a greater number of graduate programs.

Initially, the new institution carried over the two universities’ accreditation. The merged university was put on probation for a year, as some of the finances and separation from TSC were implemented. UTRGV was removed from probation in December of 2018.[59]

The University (UTRGV) serves a predominately Hispanic population with about 89 percent Hispanic students in 2015 – 2019 (see Figure 4a). The primary equity considerations behind the merger had to do with saving UTB and the students that it served. In addition, an added benefit was hoped-for improved access to health care, in addition to improving access to quality post-secondary education, including a greater number of graduate programs. There was a desire to improve the available medical care in the region, and establishing a medical school, associated with a major research institution, was seen as a way to do this.

In February of 2014, the UT System Board of Regents approved money for the construction of a needed medical school building, as well as preliminary approval for UTRGV to grant a Doctor of Medicine (M.D.)[60] A medical school was approved in 2015.[61]

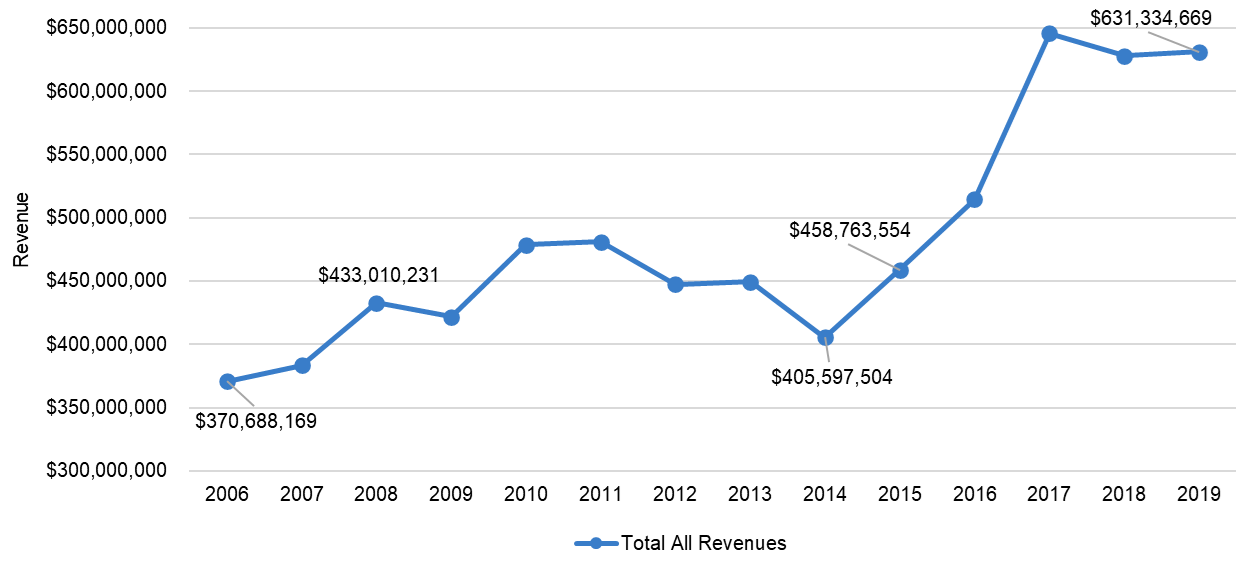

The financial data suggest that resources significantly improved, and enrollments increased at UTRGV compared to the two institutions, UTPA and UTB, before the merger.

Figure 5a: UTRGV operating revenue trends from 2006 – 2019. From 2006 – 2014 the data in this figure represents only UTPA, but from 2015 – 2019 the data depicts only UTRGV

The consolidation, of UTB and UTPA, was a success, in that the institutions were successfully merged and UTRGV has evolved into a large research university with greater access to resources. This includes support for research, through grants and other revenue streams. Total research expenditure of UTB and UTPA in 2010 was very similar to that for UTRGV in 2016, shortly after the merger at about $15 million. But, by 2019, UTRGV’s total research expenditure had increased to $30.1 million.[62]

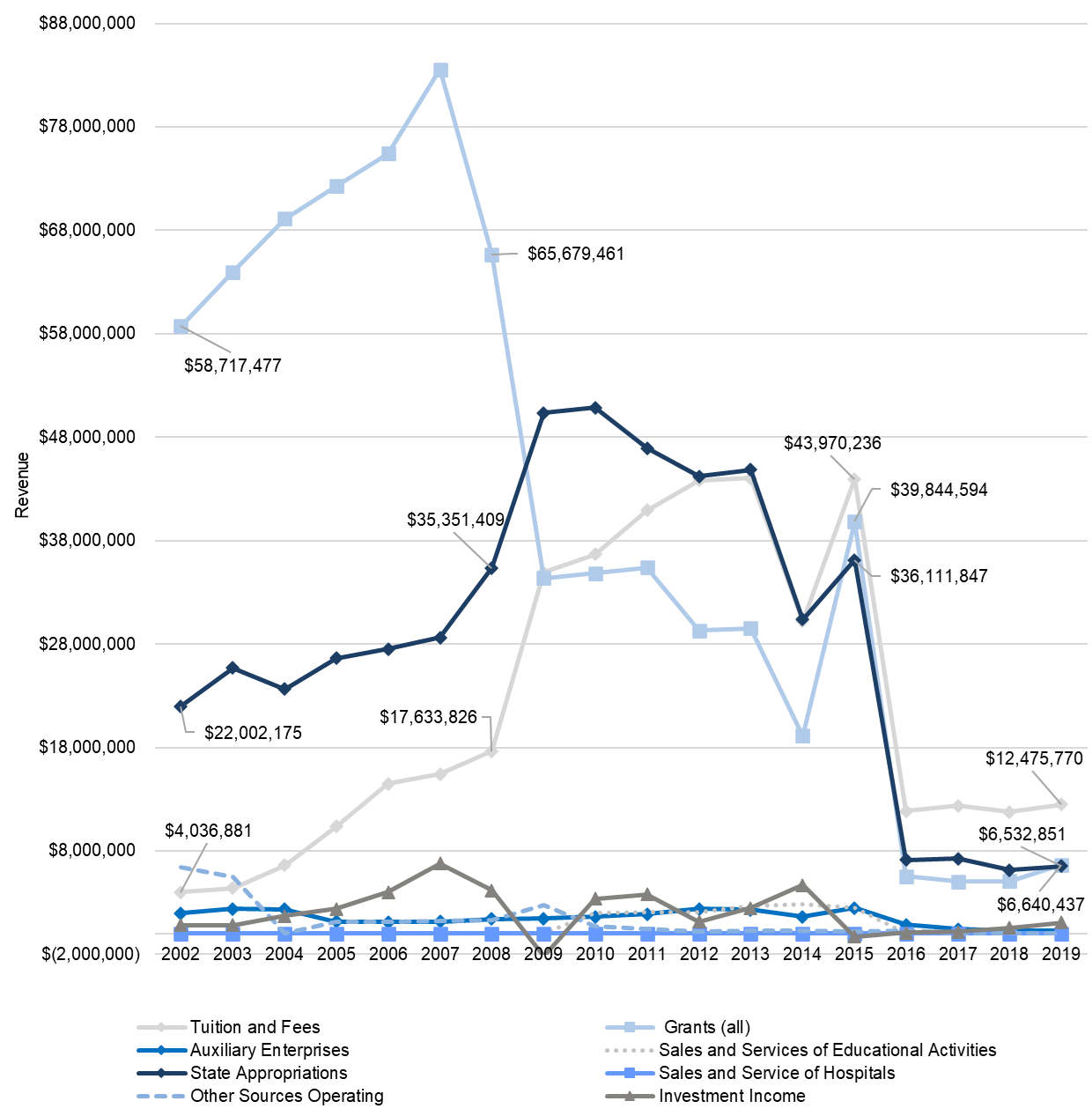

The impact on TSC was significantly more challenging. The decline in enrollments and in tuition revenue were precipitous (see Figure 6).

Figure 5b: TSC operating revenue trends from 2002 – 2019

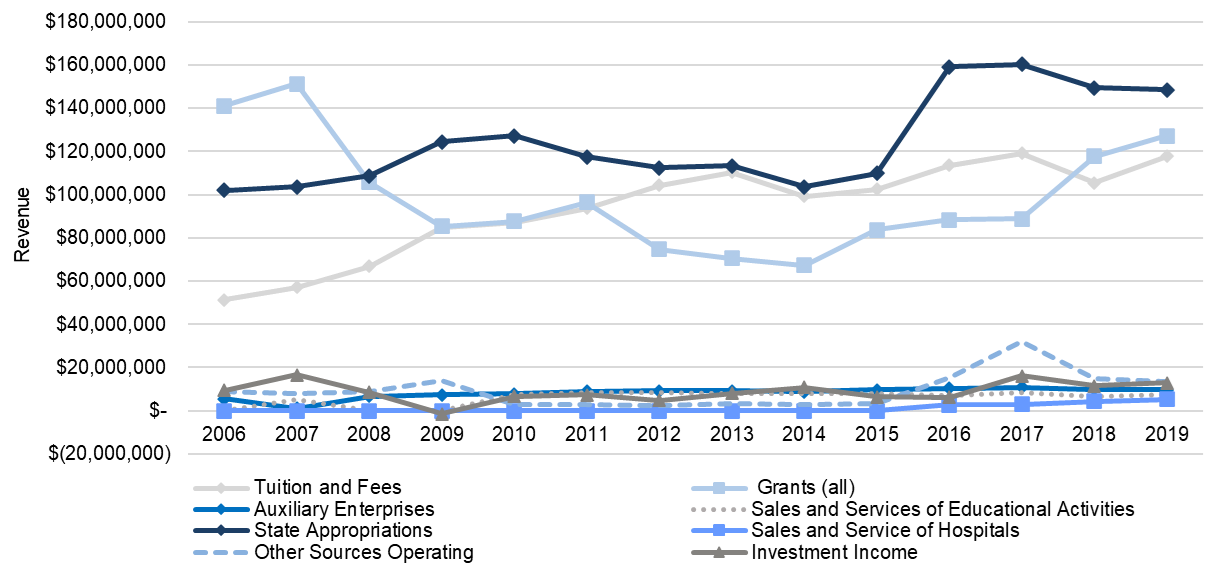

Figure 5c: Operating revenue trends for UTRGV and TSC combined from 2006 – 2019

Figure 6: Total of all revenues for UTRGV and TSC combined from 2006 – 2019.

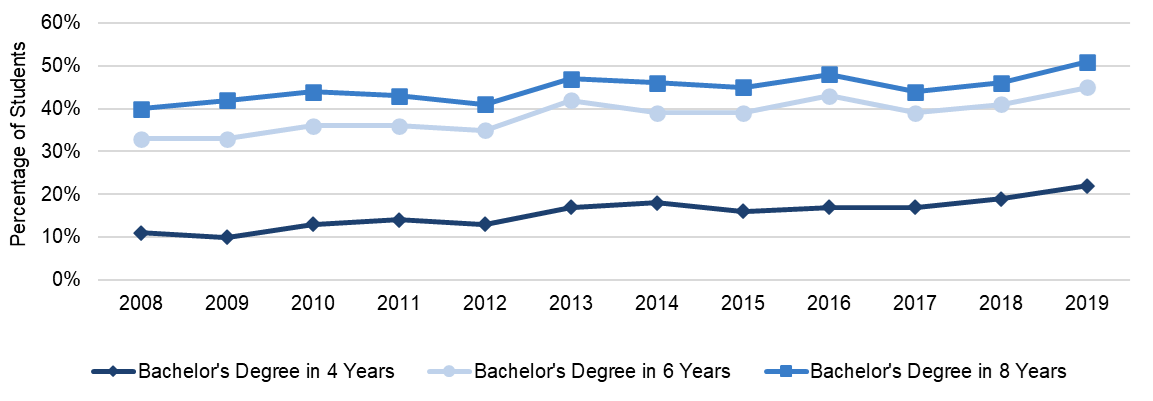

Figure 7: Percentage of students from UTRGV obtaining a bachelor’s degree in 4, 6, and 8 years.

The dips and spikes of certain races and ethnicities in this figure are due to incomplete and missing data for these races and ethnicities in IPEDS.

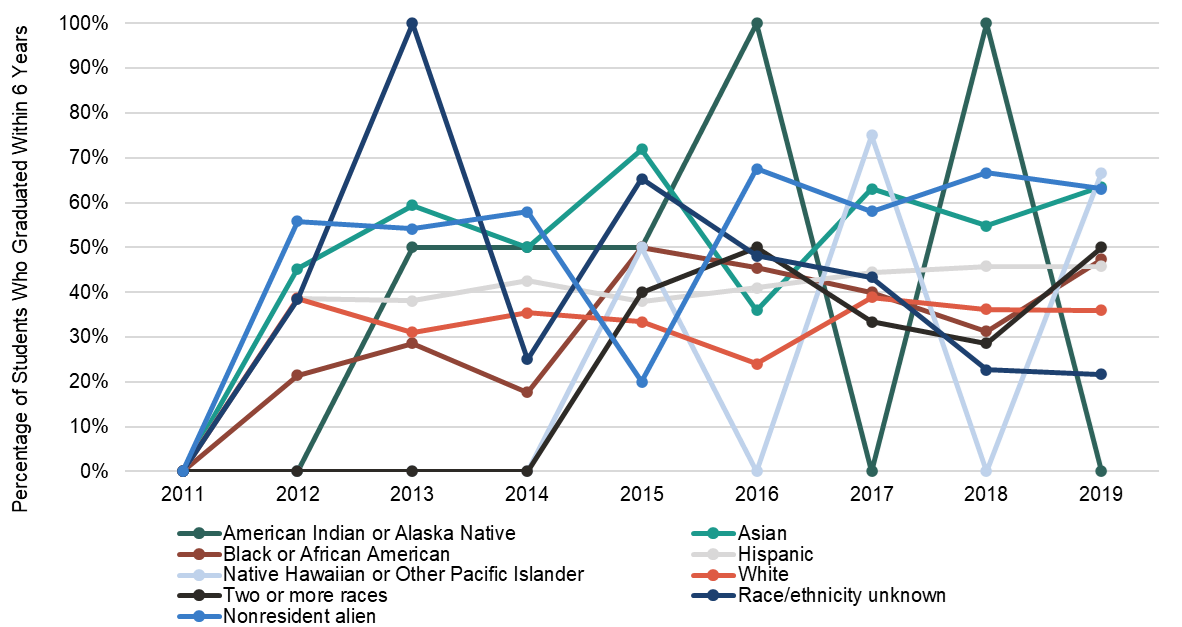

Figure 8: Percentage of students who graduated within 6 years from UTRGV by race and ethnicity from 2012 – 2019.

The dips and spikes of certain races and ethnicities in this figure are due to incomplete and missing data for these races and ethnicities in IPEDS.

While there has been some improvement in six-year graduation rates, there is significant room for further improvement. The variability in rates by race, with the exception of Hispanic students, is the result of the relatively small sample sizes, compared to the Hispanic population.

The goal of establishing a medical school was accomplished. The medical school has about 200 medical students, 200 residents and fellows across the Rio Grande Valley serving in 13 hospital-based training programs, 100 faculty, and 50 additional researchers.[63] UT Health RGV, the clinical arm of the medical school, is contributing to improving medical care in the Rio Grande Valley. In addition, the medical school is committed to educating a diverse student body, contributing to increasing the diversity of the medical profession.

In December of 2019, the system announced that it was moving forward with a plan “to merge the academic and research portions of its Tyler-based institutions.”[64] This move would put both Tyler institutions under one administrative body thereby better serving the needs of the state. One year later, in December of 2020, the UT System announced that the accreditor, SACSCOC, had approved the operational plan for the merger of UT Tyler and the UT Health Science Center at Tyler.[65] The justifications for this merger mirror many of those for the creation of a medical school, and merger of the health center, into the UTRGV. This suggests that the creation of UTRGV was considered a success by the UT System and a model to be replicated.

The relationship between the research universities and health science (medical) centers within the UT system has evolved over time. In 2011, when the merger of UTPA and UTB was announced, the UT system consisted of 15 institutions. This included seven major research institutions, six health science centers, and UTPA and UTB. The latter two were outliers in that they were not major research universities and were brought into the UT system in large part for political reasons. Through the merger, they were to be transformed into a research university, more consistent with the other members of the UT System. Merging the existing regional health center into the combined university, UTRGV, and adding a medical school created a new model within the UT System. UT Austin at the time was also moving in this direction and added a medical school. Of the remaining six health science centers, four include medical schools.

Over the last 20 years, there were two attempts to merge a research university (or two) with a health center, including a medical school. These mergers failed, because one or more of the institutions did not see it in their interests to merge. In January of 2021, a merger took place between UT Tyler and UT Health Science Center at Tyler,[66] with plans to add a medical school in 2023. The experiences of the UT System suggest that merging existing institutions can more easily happen when something new is made possible, such as a new medical school, which helps the various constituencies involved not see the merger as zero sum. But, when the merger is designed to strengthen one of the institutions and is perceived to damage the other institution, resistance arises. While a merger between UT San Antonio and UT Health Science Center at San Antonio might have benefited UTSA’s science/medical research capacity, the health science center, already thriving, saw little gain that would justify suffering through the disruption of a merger.

Lessons Learned

Consolidations are easier when they are targeted at growth rather than retrenchment. This made the politics involved in the UTRGV merger significantly easier, as both communities believed they would benefit from the merger, despite the fact that some administrative cost savings would be realized. Overall, there was an expectation for job growth and greater resources from the state in this case. But, even in this situation, the transition from one set of relationships to another involved significant disruption for faculty and staff. As we are seeing in other efforts at consolidation across the country, those constituencies that expect to lose, or fear they may lose, often resist change. Easing transition costs for individuals and making it clear that this will be part of the consolidation, may help avoid resistance. Again, this will be easier in a growth situation, since there will be fewer groups expected to lose from the consolidation.

The relationship between the dissolution of the UTB and TSC agreement and the founding of a medical school may make this example less transferable to other situations. Although, it does suggest that a crisis situation can facilitate positive change. If UTB and TSC had reached a new agreement, it seems possible that UTRGV would never have come into being. And the transition of UTB and UTPA into a “new” institution is what allowed for additional resources supporting its growth into a major research institution, which in turn has generated many of the benefits for the region and the state. The idea that the merger would benefit the community in more than one way also gained support for the consolidation.

Consolidations or mergers, particularly within state systems, are inherently political events. With most institutions being regional in one way or another, mergers are difficult to construct in ways that everyone perceives as beneficial. When some constituency feels they are losing out compared to another, state legislatures of course become involved. This often privileges the status quo, even if change would ultimately be in the interests of the state.

In a way, the failure of UTB and TSC to reach a new “agreement” in 2010 after 20 years of deep integration could be interpreted as a failed merger. It seemed clear that the UT System wanted greater authority and TSC, embodied in its board, worried about losing its identity and purpose, common concerns with other consolidations. The then-TSC board chairman stated at the time, referring to UTB and the breakup, “They needed it to raise their level of excellence,” and “we needed it to be able to refocus on the basic community college mission, because it was being forgotten.”[67] If this “merger” had been successful, it is possible that the region would have been worse-off. The community college might have effectively disappeared, and the two UT institutions might have failed to grow into a stronger research university supporting a medical school.

The creation of UTRGV took place after more than 40 years of activism in Texas to reduce discrimination across public higher education against Hispanic—particularly Mexican American—and Black students. In addition to a string of named initiatives, from The South Texas Border Initiative to the later Closing the Gaps (2000), in 1996 the Supreme Court decision in Hopwood vs. State of Texas limiting affirmative action in admissions ultimately led to the 2007 Texas 10 Percent Plan.[68] This law, aimed at increasing racial and ethnic diversity at the state’s top institutions, guarantees Texas students who graduated in the top ten percent of their high school class automatic admission to all public universities in the state. While this led to greater diversity in the state’s more selective and better resourced public institutions, differentials in post-secondary educational attainment persisted by race and ethnicity.[69] Continued progress in addressing these differentials will require greater access across the state to adequately funded institutions of higher education, which the creation of UTRGV helped to accomplish, along with continued increases in diversity across those institutions in the state with the highest rates of success in graduating their students. The former should be a complement, not a substitute, for the latter. It is not clear whether the state investments in UTRGV were in part designed to take some pressure off the state flagships in response to the Texas 10 Percent Plan, but the creation of another better funded research university would have done this to some extent.

The UT system may have some lessons for the relationship between research universities and medical schools. While beyond the scope of this paper, medical schools and their associated research and clinical endeavors, including hospitals in some cases, are large relative to the overall size of research universities around the country. At the same time, the medical school/clinical practice/research arms of larger research universities are facing significant risks, from changes in government policies around health care and support for research. Many universities are considering how to manage these increasing risks. Texas has different models for research universities and health science centers, including medical schools, which might shed some light on these issues.

Endnotes

- Today The University of Texas System has a grand total of 13 institutions. It comprises eight academic institutions and five health institutions. The academic institutions include the following: The University of Texas at Arlington, The University of Texas at Austin, The University of Texas at Dallas, The University of Texas at El Paso, The University of Texas Permian Basin, The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, The University of Texas at San Antonio, and The University of Texas at Tyler. The health institutions in the UT system include the following: The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, and The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. The University of Texas System, “Institutions,” The University of Texas System, 2021, https://www.utsystem.edu/institutions. ↑

- Reeve Hamilton, “UT System Planning New Rio Grande Valley University,” The Texas Tribune, December 6, 2012, https://www.texastribune.org/2012/12/06/ut-system-planning-rio-grande-valley-university/. ↑

- Kevin Kiley, “Everything’s Getting Bigger in Texas,” Inside Higher Ed, December 7, 2012, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2012/12/07/ut-system-merges-brownsville-and-pan-am-campuses-eye-toward-new-medical-school. ↑

- Lydia Lum, “Texas University Breaking Ties With Community College,” Diverse Issues In Higher Education, October 11, 2011, http://diverseeducation.com/article/16512/.↑

- Albert H. Kauffman, “Latino Education in Texas: A History of Systematic Recycling Discrimination,” St. Mary’s Law Journal 50, no. 3 (October 2019): 861–916 https://commons.stmarytx.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1037&context=thestmaryslawjournal. ↑

- Adams v. Richardson, No. Civ. A. 3095-70 (US District Court, District of Columbia 1972). ↑

- Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, “The Texas Plan for Equal Educational Opportunity: A Brief History” (Texas State Library and Archives Commission, November 1997), http://www.thecb.state.tx.us/DocID/PDF/0021.PDF. ↑

- Al Kauffman, “Lawsuit Improved Border Higher Education,” El Paso Times, May 28, 2016, https://www.elpasotimes.com/story/opinion/2016/05/28/kauffman-lawsuit-improved-border-higher-education/85097518/; Ricardo Ray Ortegón, “LULAC v. Richards: The Class Action Lawsuit That Prompted the South Texas Border Initiative and Enhanced Access to Higher Education for Mexican Americans Living Along the South Texas Border” (Doctoral Thesis, Boston, MA, Northeastern University, 2013), https://doi.org/10.17760/d20003395. ↑

- Albert H. Kauffman, “Latino Education in Texas: A History of Systematic Recycling Discrimination,” St. Mary’s Law Journal 50, no. 3 (October 2019): 861–916 https://commons.stmarytx.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1037&context=thestmaryslawjournal. ↑

- Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, “The Texas Plan for Equal Educational Opportunity: A Brief History” (Texas State Library and Archives Commission, November 1997), http://www.thecb.state.tx.us/DocID/PDF/0021.PDF; Grady Price Blount and Robert G. Rodriguez, “Hispanics in Texas Higher Education: An Assessment of the State ‘Closing the Gaps’ Initiative,” European Scientific Journal 1, Special Edition (May 2015): 191–211, https://eujournal.org/index.php/esj/article/view/5556. ↑

- Aaron Nelsen, “Name for Merged University Is UT-Rio Grande Valley,” MY SA, December 12, 2013, https://www.mysanantonio.com/news/local/article/Name-for-merged-university-is-UT-Rio-Grande-Valley-5058373.php. ↑

- “History of The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley,” The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, 2020, https://www.utrgv.edu/en-us/about-utrgv/history/index.htm. ↑

- “History of Texas Southmost College,” Texas Southmost College, 2021, https://www.tsc.edu/about/the-history-of%20Texas-Southmost-College/. ↑

- Wikipedia, “University of Texas System,” Wikipedia, April 16, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/University_of_Texas_System. ↑

- “History of The University of Texas System,” The University of Texas System, 2021, https://www.utsystem.edu/about/history-university-texas-system. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Beth Cortez-Neavel, “In Brownsville, Two Colleges Split and a Community Suffers,” Texas Observer, May 23, 2013, https://www.texasobserver.org/in-brownsville-two-colleges-split-and-a-community-suffers/. ↑

- David Moltz, “Let’s Make a Deal,” Inside Higher Ed, October 19, 2010, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2010/10/19/lets-make-deal. ↑

- “Juliet Garcia to Join UT System as Advisor on Community, National and Global Engagement,” The University of Texas System, March 9, 2016, https://www.utsystem.edu/news/2016/03/09/juliet-garcia-join-ut-system-advisor-community-national-and-global-engagement. ↑

-

Julieta V. Garcia, then President of TSC, worked with members of her Board along with the Chancellor of the University of Texas System to make this happen in response to the many challenges facing the college at the time. These included a significant depreciation in the Mexican peso and reductions in oil prices, both of which had significant negative effects on the economy of the region.↑

- “UTB/TSC Educational Partnership Agreement,” The University of Texas System, November 10, 2010, https://www.utsystem.edu/news/2010/11/10/utbtsc-educational-partnership-agreement. ↑

- “Remarks by the UT System Chancellor Francisco G. Cigarroa, M.D. with Regard to the Partnership Agreement Between The University of Texas at Brownsville and Texas Southmost College,” November 10, 2010, https://utsystem.edu/sites/default/files/news/assets/fgcremarks-statement-utb-11-10-10.pdf. ↑

- Lydia Lum, “Texas University Breaking Ties With Community College,” Diverse Issues In Higher Education, October 11, 2011, http://diverseeducation.com/article/16512/. ↑

-

The University of Texas System has a grand total of eight academic institutions and five health institutions. The academic institutions include the following: The University of Texas at Arlington, The University of Texas at Austin, The University of Texas at Dallas, The University of Texas at El Paso, The University of Texas Permian Basin, The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, The University of Texas at San Antonio, and The University of Texas at Tyler.↑

- Aaron Nelsen, “Perry Marks University Merger Bill in Valley,” MY SA, July 16, 2013, https://www.mysanantonio.com/news/politics/texas_legislature/article/Perry-marks-university-merger-bill-in-Valley-4668531.php; Martha May Tevis, “Reflections on the Termination of Two Universities and the Creation of a New University,” Journal of Philosophy & History of Education 65, no. 1 (2015): 112, http://www.journalofphilosophyandhistoryofeducation.com/jophe65.pdf. ↑

- “2011 Texas Public Higher Education Almanac,” Almanac (Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, 2011), https://reportcenter.highered.texas.gov/agency-publication/almanac/2011-texas-public-higher-education-almanac. ↑

- Kevin Kiley, “Everything’s Getting Bigger in Texas,” Inside Higher Ed, December 7, 2012, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2012/12/07/ut-system-merges-brownsville-and-pan-am-campuses-eye-toward-new-medical-school. ↑

- Several people attributed the idea of creating a new institution out of UTB and UTPA to Steven Collins, at the time working in the UT System offices with the chancellor. ↑

- “Texas Constitution,” § Article 7, Section 18 (2019), https://statutes.capitol.texas.gov/. ↑

- “The Permanent University Fund (PUF),” The University of Texas System, 2021, https://www.utsystem.edu/puf; Office of the Chancellor, “Understanding PUF: What Is the Permanent University Fund,” The University of Texas System, August 22, 2016, https://www.utsystem.edu/offices/chancellor/blog/what-is-the-permanent-university-fund. ↑

-

Conversation with Steven Collins, July 2021.↑

- “The Permanent University Fund and Available University Fund,” The University of Texas System, 2017, 1–5, https://www.utsystem.edu/sites/default/files/offices/governmental-relations/PUF%20%20and%20AUF%20Issue%20Brief_2018%20Update.pdf. ↑

- Based on conversations with members of the UT System at the time. ↑

- Based on conversations with members of the UT System at the time. ↑

- “National Research University Fund Eligibility,” A Report to the Comptroller and the Texas Legislature (Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, March 2021), https://reportcenter.highered.texas.gov/reports/legislative/national-research-university-fund-eligibility-2021/. ↑

- Kevin Kiley, “Everything’s Getting Bigger in Texas,” Inside Higher Ed, December 7, 2012, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2012/12/07/ut-system-merges-brownsville-and-pan-am-campuses-eye-toward-new-medical-school. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- “Regents Name Guy Bailey Sole Finalist for President of UTRGV,” The University of Texas System, April 28, 2014, https://www.utsystem.edu/news/2014/04/28/regents-name-guy-bailey-sole-finalist-president-utrgv. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Martha May Tevis, “Reflections on the Termination of Two Universities and the Creation of a New University,” Journal of Philosophy & History of Education 65, no. 1 (2015): 112, http://www.journalofphilosophyandhistoryofeducation.com/jophe65.pdf. ↑

- Reeve Hamilton, “After 20 Years, a Messy Divorce in Brownsville,” The Texas Tribune, November 4, 2011, https://www.texastribune.org/2011/11/04/after-20-years-messy-divorce-brownsville/. ↑

- Lydia Lum, “Texas University Breaking Ties With Community College,” Diverse Issues In Higher Education, October 11, 2011, http://diverseeducation.com/article/16512/. ↑

- Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC), “2015 Annual Report,” (SACSCOC, 2015), https://sacscoc.org/app/uploads/2020/01/2015_Annual_Report.pdf; “TSC Announces Completion of SACSCOC On-Site Visit,” Texas Southmost College, August 20, 2015, https://www.tsc.edu/news-and-events/2015/08/20/tsc-announces-completion-of-sacscoc-on-site-visit/. ↑

- Guy Bailey, “Message from the President,” The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, December 6, 2016, https://www.utrgv.edu/en-us/about-utrgv/office-of-the-president/presidents-message/2016/december-06-2016/index.htm. ↑

- Doug Lederman, “A Watchdog Bites,” Inside Higher Ed, December 7, 2016, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2016/12/07/southern-accreditor-places-10-probation-including-louisville-and-new-ut-campus. ↑

- Beth Cortez-Neavel, “In Brownsville, Two Colleges Split and a Community Suffers,” Texas Observer, May 23, 2013, https://www.texasobserver.org/in-brownsville-two-colleges-split-and-a-community-suffers/. ↑

- Martha May Tevis, “Reflections on the Termination of Two Universities and the Creation of a New University,” Journal of Philosophy & History of Education 65, no. 1 (2015): 112, http://www.journalofphilosophyandhistoryofeducation.com/jophe65.pdf. ↑

- “2011 Texas Public Higher Education Almanac,” Almanac (Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, 2011), https://reportcenter.highered.texas.gov/agency-publication/almanac/2011-texas-public-higher-education-almanac/; T “2017 Texas Public Higher Education Almanac,” Almanac (Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, Spring 2017), https://reportcenter.highered.texas.gov/agency-publication/almanac/2017-texas-public-higher-education-almanac/; “2020 Texas Public Higher Education Almanac,” Almanac (Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, Summer 2020), https://reportcenter.highered.texas.gov/agency-publication/almanac/2020-texas-public-higher-education-almanac/. ↑

- “2011 Texas Public Higher Education Almanac,” Almanac (Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, 2011), https://reportcenter.highered.texas.gov/agency-publication/almanac/2011-texas-public-higher-education-almanac/; “2017 Texas Public Higher Education Almanac,” Almanac (Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, Spring 2017), https://reportcenter.highered.texas.gov/agency-publication/almanac/2017-texas-public-higher-education-almanac/. ↑

- Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, “Almanac – Report Center,” 60x30TX, 2021, https://reportcenter.highered.texas.gov/agency-publication/almanac/. UTB enrolments reported in the Almanac do not include TSC numbers. ↑

- The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, “Articulation Agreements,” Undergraduate Admissions Division of Strategic Enrollment and Student Affairs, 2021, https://www.utrgv.edu/undergraduate-admissions/transfer-students/articulation-agreements/index.htm#stc. ↑

-

Based on conversations with Julieta V. Garcia, July 2021.↑

- Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, various annual issues. ↑

- “2011 Texas Public Higher Education Almanac,” Almanac (Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, 2011), https://reportcenter.highered.texas.gov/agency-publication/almanac/2011-texas-public-higher-education-almanac/; Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, “2017 Texas Public Higher Education Almanac,” Almanac (Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, Spring 2017), https://reportcenter.highered.texas.gov/agency-publication/almanac/2017-texas-public-higher-education-almanac/; “2020 Texas Public Higher Education Almanac,” Almanac (Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, Summer 2020), https://reportcenter.highered.texas.gov/agency-publication/almanac/2020-texas-public-higher-education-almanac/. ↑

- “TSC Strategic Plan,” Texas Southmost College, 2021, https://www.tsc.edu/about/tsc-strategic-plan/. ↑

- Scott Jaschik, “10 Percent Plan Survives in Texas,” Inside Higher Ed, May 29, 2007, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2007/05/29/10-percent-plan-survives-texas; Nicholas Webster, “Analysis of the Texas Ten Percent Plan” (The Ohio State University: Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity, 2007), http://kirwaninstitute.osu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Texas-Ten-Percent_style.pdf; Barrientos, “Texas House Bill 588,” Pub. L. No. HB 588 (1997), https://capitol.texas.gov/billlookup/text.aspx?LegSess=75R&Bill=HB588; UT News, “Top 10 Percent Law,” The University of Texas at Austin, https://news.utexas.edu/key-issues/top-10-percent-law/. ↑

- “2011 Texas Public Higher Education Almanac,” Almanac (Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, 2011), https://reportcenter.highered.texas.gov/agency-publication/almanac/2011-texas-public-higher-education-almanac. ↑

- “2017 Texas Public Higher Education Almanac,” Almanac (Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, Spring 2017), https://reportcenter.highered.texas.gov/agency-publication/almanac/2017-texas-public-higher-education-almanac/. Institutions were granted autonomy in setting tuition and fees, leading to greater differences across institutions. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/10.7758/rsf.2016.2.1.06.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A08aa5a9dbae5ad40c42215f0c8090735 ↑

- “UTRGV Is Removed from Probationary Status,” Texas Border Business, December 11, 2018, https://texasborderbusiness.com/utrgv-is-removed-from-probationary-status/; Joanna Guzman, “UTRGV No Longer On Probationary Status,” Rio Grande Valley News & Weather, December 12, 2018, https://www.valleycentral.com/news/local-news/utrgv-no-longer-on-probationary-status/. ↑

- “Regents Move Forward with Creation of Medical School in Rio Grande Valley,” The University of Texas System, February 7, 2014, https://www.utsystem.edu/news/2014/02/07/regents-move-forward-creation-medical-school-rio-grande-valley; “Regents Approve Medical Degree Program for UTRGV,” The University of Texas System, July 10, 2014, https://www.utsystem.edu/news/2014/07/10/regents-approve-medical-degree-program-utrgv. ↑

- “Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board Approves Medical Degree for UTRGV School of Medicine,” The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, April 23, 2015, https://www.utrgv.edu/en-us/about-utrgv/news/press-releases/2015/april-23-medical-degree-award/index.htm. ↑

- “2017 Texas Public Higher Education Almanac,” Almanac (Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, Spring 2017), 34-35, https://reportcenter.highered.texas.gov/agency-publication/almanac/2017-texas-public-higher-education-almanac/; “2020 Texas Public Higher Education Almanac,” Almanac (Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, Summer 2020), 40, https://reportcenter.highered.texas.gov/agency-publication/almanac/2020-texas-public-higher-education-almanac/. ↑

- “Welcome from the Dean,” UTRGV School of Medicine, 2021, https://www.utrgv.edu/school-of-medicine/. ↑

- Cory McCoy, “UT System To Move Forward With Merger of UT Tyler and Health Science Center,” Tyler Morning Telegraph, December 9, 2019, https://tylerpaper.com/news/local/ut-system-to-move-forward-with-merger-of-ut-tyler-and-health-science-center/article_eafcc81e-1ac1-11ea-8469-1b566647a8c6.html. ↑

- “Statement from The University of Texas System on the Merger of UT Tyler and UT Health Science Center at Tyler,” December 9, 2020, https://www.utsystem.edu/news/2020/12/09/statement-university-of-texas-system-merger-of-ut-tyler-and-ut-health-science-center-at-tyler. ↑

- “Statement from The University of Texas System on the Merger of UT Tyler and UT Health Science Center at Tyler,” December 9, 2020, https://www.utsystem.edu/news/2020/12/09/statement-university-of-texas-system-merger-of-ut-tyler-and-ut-health-science-center-at-tyler; “UT Tyler Announces Executive Leadership for Merged Institution,” The University of Texas at Tyler, January 15, 2021, https://www.uttyler.edu/news/pressrelease/2021/01152021.php. ↑

- Reeve Hamilton, “After 20 Years in Partnership, an Educational Combo Is Getting a Messy Divorce,” The New York Times & The Texas Tribune, November 3, 2011, https://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/04/us/after-20-years-in-partnership-an-educational-combo-is-getting-a-messy-divorce.html. ↑

- Scott Jaschik, “10 Percent Plan Survives in Texas,” Inside Higher Ed, May 29, 2007, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2007/05/29/10-percent-plan-survives-texas; Nicholas Webster, “Analysis of the Texas Ten Percent Plan” (The Ohio State University: Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity, 2007), http://kirwaninstitute.osu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Texas-Ten-Percent_style.pdf; Barrientos, “Texas House Bill 588,” Pub. L. No. HB 588 (1997), https://capitol.texas.gov/billlookup/text.aspx?LegSess=75R&Bill=HB588; UT News, “Top 10 Percent Law,” The University of Texas at Austin, https://news.utexas.edu/key-issues/top-10-percent-law/. ↑

- Grady Price Blount and Robert G. Rodriguez, “Hispanics in Texas Higher Education: An Assessment of the State ‘Closing the Gaps’ Initiative,” European Scientific Journal 1, Special Edition (May 2015): 191–211, https://eujournal.org/index.php/esj/article/view/5556.↑