Funding Socioeconomic Diversity at High Performing Colleges and Universities

This report is published on behalf of the American Talent Initiative (ATI). ATI is a partnership between Bloomberg Philanthropies, the Aspen College Excellence Program, Ithaka S+R, and a growing alliance of top colleges and universities collaborating on a national goal: educating an additional 50,000 low-to-moderate income students by 2025. ATI members are working together to identify the best ways to attract the talent pool that is now missing from top colleges and to share the best practices for providing those students with the support they need to be successful.

ATI thanks Bloomberg Philanthropies for supporting the publication of this report.

Executive Summary

At America’s 270 four-year public and private not-for-profit colleges and universities with graduation rates consistently above 70 percent, only 22 percent of students received Pell grants in academic year 2013-2014. By contrast, nearly 38 percent of students enrolled at all other four-year public and non-profit private schools receive Pell grants. This disparity is not driven by differences in student ability. There is ample evidence that low- and moderate-income students with the talent to earn admission thrive at top institutions when their financial needs are met, and graduate at higher rates than they do at less competitive schools.

Yet, most top-performing colleges and universities consider students’ ability to pay in admissions decisions, at times accepting less talented full-pay students in order to meet revenue targets. For those lower-income applicants who are admitted, many institutions struggle to meet their full financial need. Thus, even when incredibly talented students from lower-income backgrounds are admitted to top institutions, large shares do not receive adequate support, and therefore enroll and persist at lower rates than wealthier peers.

With finite budgets and multiple priorities, institutions limit the funds they allocate to need-based aid and other programs that support low- and moderate-income students. Yet even with those constraints, there are top-performing colleges and universities that have enhanced their commitment to serving these students and have found the financial means to do so. This paper profiles five of those institutions, focusing on their strategies for allocating funding to increase opportunities for low- and moderate-income students. The institutions we profile are:

- Franklin & Marshall College, which nearly tripled the share of Pell recipients in its incoming class between 2008 and 2016 by fostering an institutional commitment to an innovative “talent strategy,” eliminating merit-only aid and gradually reallocating other funds to need-based aid, and forming strategic partnerships with K-12 organizations.

- University of California, Berkeley, which, despite declining state funding, maintained high enrollment levels of low- and moderate-income students by increasing tuition, streamlining administrative expenses, and allocating a portion of tuition revenue and saved expenses towards need-based aid.

- University of Richmond, which increased its enrollment of Pell recipients from 9 percent in 2008-2009 to 13 percent in 2013-2014 by leveraging a strategic planning process, data-driven enrollment planning and aid policies, and careful management of its endowment.

- University of Texas at Austin, which maintained high enrollment levels of low- and moderate-income students and increased graduation rates by strategically using one-time grants to jump-start innovative student aid and support programs and using modeling to ensure program effectiveness.

- Vassar College, which tripled the share of Pell recipients by maintaining generous aid policies, increasing the commitment of endowment earnings to financial aid, deferring capital projects, and bringing compensation costs in line with peer institutions.

These institutions face different challenges and have different capacities related to factors such as their sector, endowment, size, and ability to expand. Nevertheless, each has pulled a different combination of the following financial levers to support increasing opportunity:

- Reallocating funds from merit-only aid to need-based aid;

- Making strategic use of one time grants and budgetary surpluses;

- Cutting non-instructional expenses through administrative streamlining, reductions in clerical and maintenance staff, or deferring capital projects;

- Increasing revenue through growing enrollment, increasing tuition, fundraising, and other revenue generating strategies; and

- Drawing from the endowment in strategic ways.

Additionally, the five profiled institutions have employed some common transition strategies to implement these reallocations effectively and reinforce their commitment to access and success. Specifically:

- Their leaders have visibly committed to and communicated about goals for increasing opportunity, and have framed these aims as good for their institutions as well as for the broader public.

- They have used data to persuade internal and external audiences, to identify opportunities for reducing costs, and to better target aid and support.

- They have understood the need to engage faculty, boards, and other stakeholders in a gradual and widely-supported process of change by giving stakeholders a role in budget reallocation decisions, phasing-in budgetary reallocations, and using other tactics to deepen understanding of the value of increasing socio-economic diversity.

If given the opportunity, talented low- and moderate-income students thrive at high-performing colleges and universities. America’s top institutions can help to create these opportunities, but doing so requires new practices and new financial commitments. The five institutions profiled here offer illustrative examples of what it takes to enhance efforts to promote opportunity despite significant financial constraints. In each case, strategic cost containment has been a critical strategy for reallocating funds to financial aid and other supports for low- and moderate-income students. Such tradeoffs inevitably create some conflicts, and what distinguishes these institutions, in part, are their transition strategies. While each institution has faced bumps in the road, these strategies have enabled them to reallocate funds in ways that are financially sustainable, maximally effective, and broadly supported by institutional stakeholders.

Introduction

At America’s 270 four-year public and private not-for-profit colleges with graduation rates consistently above 70 percent, only 22 percent of students received Pell grants in academic year 2013-2014. By contrast, nearly 38 percent of students enrolled at all other four-year public and non-profit private schools receive Pell grants.[1] This disparity is not driven by differences in student ability, but rather by admissions, financial aid, and support policies that do too little to promote opportunity and access. Even when low- and moderate-income students overcome the significant barriers to applying to top schools, without adequate support, they are less likely to be admitted, enroll, and persist at top institutions than their wealthier peers.[2]

There is ample evidence that low- and moderate-income students thrive at top institutions when their financial needs are met.[3] Yet, most top-performing colleges and universities consider students’ ability to pay in admissions decisions, turning away qualified lower-income applicants in favor of less-qualified applicants who can afford full tuition. Moreover, most institutions struggle to meet all admitted students’ full financial need.

With finite budgets and multiple priorities, institutions limit the funds they allocate to need-based aid and other programs that support low- and moderate-income students.[4] Even institutions with large endowments faced losses and restrictions on use during the Great Recession and its aftermath, and many struggled to devise robust alternative strategies for maintaining aid. Private institutions with smaller endowments have always had to rely more on tuition and fees for revenue, and finding ways to maintain or increase financial aid has become increasingly difficult. State funding of public institutions has declined over the past twenty years and at an accelerating rate since the recession, and many public institutions have increased tuition and made other hard tradeoffs.

Yet even with those constraints, there are top-performing colleges and universities that have enhanced their commitment to serving low- and moderate-income students and have found the financial means to do so. These institutions have recognized their potential to act as engines of social mobility and acknowledged their responsibility, as organizations that receive public support, to do so. From the dozens of institutions in that category, this paper profiles five examples, focusing on their strategies for allocating funding to increase opportunities for low- and moderate-income students. The institutions we profile are:

- Franklin & Marshall College

- University of California, Berkeley

- University of Richmond

- University of Texas at Austin

- Vassar College

By design, we have chosen institutions that face different challenges and have different capacities, depending on circumstances like their sector, endowment, size, and ability to expand. Nevertheless, each of these institutions, like others, has pulled a different combination of the following financial levers to support increasing opportunity. These include:

- Reallocating funds from merit-only aid to need-based aid.

- Making strategic use of one-time grants and budgetary surpluses to support increases in aid and support programs.

- Cutting non-instructional expenses through administrative streamlining, reductions in clerical and maintenance staff, or deferring capital projects.

- Increasing revenue through growing enrollment, tuition increases, fundraising, or other strategies, and implementing policies that ensure that a portion of new revenue is allocated towards aid and support programs.

- Drawing from the endowment when financial conditions allow, and managing endowment draws strategically.

Regardless of their specific combination of tactics, each institution we profile has faced—and overcome—notable challenges in allocating funds for need-based financial aid and student support programs. Every dollar spent on financial aid or another program to support low- and moderate-income students is a dollar not spent on some other institutional goal, and all of these institutions had to rely on cost-cutting to some extent to support their efforts. At the end of the day, each of these colleges and universities has increased opportunity because its leaders made doing so a priority. This commitment has paid off: in addition to increasing the share of low- and moderate-income students that they enroll, each profiled institution graduates students who receive Pell Grants at rates that are nearly as high as students who do not receive Pell Grants, and rates that are much higher than the national average (see Table 1).[5]

Table 1: Six-year graduation rates for Pell and non-Pell students

| Institution | 6-Year Pell Graduation Rate for first-time, full-time freshman (2013) | 6-Year non-Pell Graduation Rate for first-time, full-time freshman (2013) |

|---|---|---|

| Franklin & Marshall College | 86.3% | 87.4% |

| University of California, Berkeley | 87.7% | 92.2% |

| University of Richmond | 81.9% | 85.3% |

| University of Texas at Austin | 70.0% | 81.4% |

| Vassar College | 88.6% | 94.3% |

| All Institutions* *Analysis includes 1,149 institutions. | 50.7% | 64.9% |

| Source: Andrew Howard Nichols, “The Pell Partnership: Ensuring a Shared Responsibility for Low-Income Student Success,” The Education Trust (September 2015), https://edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/ThePellPartnership_EdTrust_20152.pdf. Many student success initiatives at UT Austin, which has the largest graduation gap of any school, have been targeted specifically at low-income students who are at the highest risk of not graduating. | ||

Despite their differences, the five profiled institutions have employed some common strategies to implement these reallocations effectively and reinforce their commitment to access and success. Specifically:

- Their leaders have visibly committed to and communicated about goals for increasing opportunity and have framed these aims as furthering both the mission of their institutions and their responsibility to the broader public good.

- They have used data to persuade internal and external audiences, to identify opportunities for reducing costs, and to better target aid and support.

- They have understood the need to engage faculty, boards, and other stakeholders in a gradual and widely supported process of change by giving stakeholders a role in budget reallocation decisions, phasing-in budgetary reallocations, and using other tactics to deepen understanding of the value of increasing socio-economic diversity.

The profiles that follow summarize the particular ways that the five example institutions applied these strategies.

Franklin & Marshall College

Key Takeaways

Successes

- Nearly tripled its need-based financial aid budget and the share of Pell Grant recipients in its incoming class between 2008 and 2016.

- Increased retention and graduation rates as its student body has grown more diverse.

Challenges

- Constrained by a smaller endowment than many peer schools; must do “a lot with a little.”

Strategies

- Shifted nearly all aid funding to need-based aid, and committed to meeting students’ full need.

- Relied on a “phasing approach” to gradually reallocate funds that had previously been built into the budget as surpluses.

- Rethought institutional definitions of talent and excellence and embedded these values into the strategic plan and messaging, as well as recruitment, admission, and support strategies.

- Forged partnerships with numerous high-performing K-12 organizations to maximize recruitment.

From 2006 to 2008, the average share of Pell Grant recipients in Franklin and Marshall’s incoming classes was 7 percent. For the incoming classes of 2014, 2015, and 2016, this average was 19 percent.[6] To support the growing share of students with need, Franklin & Marshall increased its need-based financial aid budget for each cohort from $5 million to $13 million from 2007 to 2014. Additionally, from 2012 to 2016, Franklin and Marshall decreased the average indebtedness of graduating students by 19 percent, from $33,200 to $27,060.[7]

Through its “Next Generation Initiative,” Franklin & Marshall also formed partnerships with high-performing K-12 schools and college access programs; created a pre-college summer program for high-performing, low-income students called F&M College Prep; and expanded its partnership with the Posse Foundation to enroll an annual cohort of STEM scholars drawn from underrepresented communities in Miami in addition to its existing Posse scholars from New York City.[8] It has also developed new institutional resources to assess and meet the needs of first generation college students, including the recruitment of a national expert to lead this work.[9]

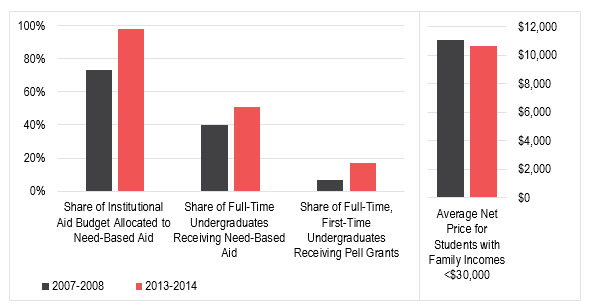

Figure 1. Franklin & Marshall College Need-Based Aid, Pell Grant Recipients, and Net Price

Sources:

Need-Based Aid Data: Franklin & Marshall College Common Data Set.

Pell Grant & Net Price Data: IPEDS. Net price data represented in nominal terms.

Franklin & Marshall has relied on a “phasing approach” to reallocate funds from merit-only aid, year-end budgetary surpluses, capital projects, and new revenue to these initiatives. From 2007 to 2014, Franklin & Marshall increased the percentage of its first-year aid budget dedicated to need-based aid from 73 percent to 95 percent, gradually reallocating more funds from tuition discounting to need-based aid each year.[10] After reviewing analyses indicating that using merit-only aid to attract near full-pay students was not yielding the highly-qualified students the strategy was intended to recruit, the Franklin & Marshall board of trustees realized the school could more effectively recruit strong students and build a vibrant community by dedicating more funds to need-based aid. In 2010, the board hired Dan Porterfield as president because his vision for institutional excellence was aligned with this strategic direction. Porterfield’s “talent strategy” has built on the board’s instinct to prioritize academic excellence; he developed the approach as a “talent strategy.”

Shifting financial aid dollars from tuition discounts to need-based aid provided some of the funding needed to support Franklin & Marshall’s ambitious new talent strategy. To further reallocate funds, the institution gradually changed its budgeting process so that large, year-end budgetary surpluses, previously allocated near the end of fiscal years to special projects and campus construction, are now budgeted at the outset to cover plant operation costs and financial aid. Additionally, Franklin & Marshall deferred some facilities projects, incrementally reduced administrative expenses, and strategically distributed new revenue from enrollment increases and fundraising to financial aid.[11] These tactics, implemented gradually, avoided giving community members the sense that resources had to be pinched in order to support low- and moderate-income students and reinforced the notion that socioeconomic diversity (and the talent of the students being recruited) is a community asset rather than an expense. Within two years, the high retention rates and strong grades of the first large cohorts of Pell recipients, as well as the growing size and depth of the applicant pool provided evidence that the approach was working.

In order to recruit and support larger shares of low-income students, Franklin & Marshall employs a combination of data-driven and high-touch, holistic approaches. The institution relies on rigorous yield modeling to ensure it is using its aid most effectively in admissions and recruiting, and leverages partnerships with college preparation and support organizations, such as the KIPP charter school network, the College Advising Corps, College Match, and the Posse Foundation, to build a pipeline of talent. [12] With a 9-1 student-faculty ratio and highly engaged faculty, Franklin & Marshall has always been a “high-touch” environment, but it has more recently started to use data, including qualitative assessments of socio-emotional strengths, to create new programs that meet particular needs for all students.[13]

Several years into the Next Generation Initiative and the talent strategy, Franklin & Marshall serves a student body that is not only more socioeconomically diverse but also more talented and engaged. Faculty report that classroom discussion and college culture have improved. Retention and graduation rates—already high—have improved, as well, and, in 2013, the six-year graduation rate for both Pell and non-Pell students was around 87 percent.[14] Porterfield and other campus leaders have shared their story widely, and the interest and attention have yielded more highly qualified applicants, stronger fundraising, new partnerships, and a distinctive and positive reputation.

University of California, Berkeley

Key Takeaways

Successes

- Maintained the share of first-time, full-time undergraduate students who receive Pell Grants at about 25 percent, and has kept net price for low-income students under $9,000.

- Prioritized affordability and maintained one of the lowest borrowing rates among four-year universities in the country.

Challenges

- Suffered sharp decreases in state funding over the past several decades, and particularly since the Great Recession.

- Like many peer public institutions, reluctantly turned to tuition increases to support its operating budget, with public and political pushback.

Strategies

- Maintained a “return-to-aid” policy which allocates one-third of tuition and fee increases to financial aid.

- Increased revenue by temporarily increasing enrollment of out of state students, who pay more in tuition than California residents.

- Used data analysis to guide administrative streamlining and cost cutting efforts, while incentivizing innovations and philanthropy that will generate revenue for the institution.

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley) has maintained a high share of low- and moderate-income students despite significant decreases in state funding. In 2013-2014, 24 percent of first-time, full-time undergraduates received Pell Grants and 34 percent of all enrolled students received Pell Grants (this discrepancy can largely be explained by the large share of transfer students who receive Pell Grants). The average net price for students whose families earned $30,000 a year or less was $8,607.[15] Additionally, only 42 percent of undergraduates have student loans—one of the lowest borrowing rates among four-year public universities. Only 3.7 percent of student borrowers default, compared to a 13.7 percent national average, and 88 percent of first-time, full-time students who receive Pell Grants graduate within six-years (compared to 92 percent for non-Pell students).[16]

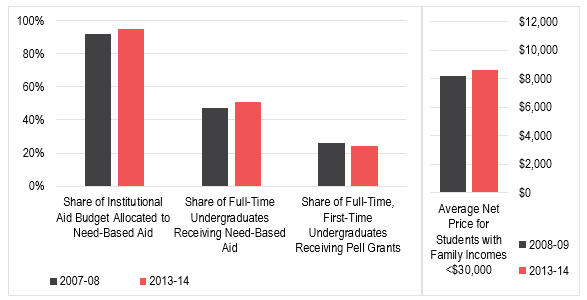

Figure 2. UC Berkeley Need-Based Aid, Pell Grant Recipients, and Net Price

Sources:

Need-Based Aid Data: UC Berkeley Common Data Set.

Pell Grant & Net Price Data: IPEDS. Net price data represented in nominal terms.

Though most public institutions have suffered cuts in state funding over the past two decades, budget cuts at UC Berkeley and other California public institutions have been particularly substantial and have accelerated since the Great Recession.[17] State general fund support for UC Berkeley declined from $506 million in 2008 to $333 million in 2015, which is just 13 percent of UC Berkeley’s $2.4 billion dollar annual budget.[18] Like other public institutions facing similar circumstances, UC Berkeley has used revenue from tuition increases to offset some of the loss in allocations from the state. From 2007 to 2013, California resident tuition and fees grew from $8,382 to $14,986.[19] UC Berkeley has also increased enrollment of out-of-state students who pay $23,000 more in annual tuition than California residents do.[20]

UC Berkeley students benefit from several University of California system (UC system) policies that prioritize affordability. First, a “return to aid” policy mandates that each institution allocate one third of all tuition revenue and one third of any fee increases to financial aid.[21] As a result, as general state funding and the share of aid provided by state and federal sources has decreased, Berkeley has allocated a greater amount of tuition revenue to financial aid. [22] Second, Berkeley students are supported by the Blue and Gold Opportunity Fund, which offers gift aid to cover tuition and fees for students whose families earn less than $80,000 a year. Finally, the Middle Class Access plan, introduced in 2014, limits tuition payments of students from families that earned between $80,000 and $150,000 a year to 15 percent of family income.[23]

While Berkeley’s tuition and out-of-state enrollment strategies brought in more than $600 million in revenue from 2010 to 2014, these decisions provoked protests and political pushback. This prompted the UC system to impose a three-year tuition freeze from academic year 2012-13 to 2014-15 and to cap out-of-state enrollment at 2015 levels. A new arrangement with the state raised state funding modestly while requiring Berkeley to enroll several hundred additional students each year and to freeze in-state tuition for an additional two years.[24]

Berkeley has also used data analysis and administrative streamlining to ensure that it can maintain its commitment to opportunity. In 2010, Berkeley launched its “Operational Excellence” initiative, which targeted excess costs and redundancies in areas such as procurement, IT, finance, and energy use, and led to cumulative savings of $112.6 million by December 2014.[25] In 2013, it launched the Revenue Generation initiative, which provides consulting services, online tools, access to campus leaders, project management, and start-up funding to help campus units generate new revenue streams.[26] While not all of these policies have been directly linked to aid, leaders report that they had freed up money in the budget so that cuts would not have to be made to financial aid.

University of Richmond

Key Takeaways

Successes

- Increased Pell Grants from 9 percent in 2007-2008 to 17 percent in 2014-2015, while increasing its need-based aid budget and discount rate.

- Maintained a no-loan policy for low-income, first-year students from Virginia since 2006.

Challenges

- Being need-blind in the admission of domestic students while also meeting the full demonstrated need of all undergraduates is expensive and adds uncertainty to year-to-year financial planning.

Strategies

- Used data-driven planning around its financial aid initiatives to ensure that it allocates aid effectively.

- Focused on delivering value and building pipelines for in-state students, who are more likely to enroll; increased outreach to target populations, and refined admission review process to implement a more holistic review.

- Incorporated a commitment to diversity and financial aid into the institution’s strategic plan and mission.

With a large endowment for an institution of its size, the University of Richmond has long maintained a need-blind admissions policy for domestic students and has committed to meet 100 percent of demonstrated need for all admitted students.[27] Notwithstanding these policies, only about 9 percent of first-year students who entered in fall 2007 received Pell grants. The institution’s leadership felt they could do more to serve a diverse population of students, particularly low- and moderate-income students from Virginia.

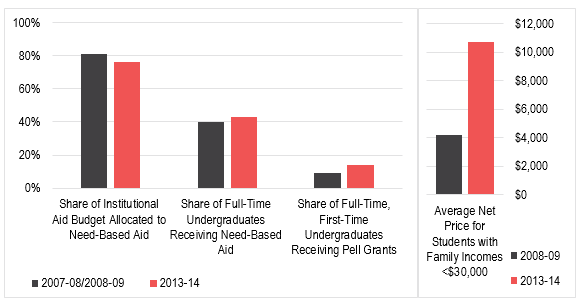

Building on a 2006 program that covered tuition, room and board with no loans for low-income Virginians, the University launched the “Richmond Promise” in 2008, a five-year strategic plan that included a commitment to “providing a transformative opportunity to excellent students by sustaining a bold program of financial aid, increasing representation of Pell-eligible and first-generation students, and making its costs transparent and understandable to families.”[28] Through this commitment to access and affordability, continued under the leadership of President Ronald A. Crutcher, the University of Richmond increased the percentage of first-time, full-time undergraduate students who receive Pell Grants from 9 percent in 2007-2008 to 17 percent in 2014-2015.[29] Over this span of time, the tuition discount rate increased from 40 percent to 46 percent, and the budget for need-based aid increased by 65 percent.[30] Even with this substantial additional funding, average net price for students with incomes below $30,000 increased during this time period, though it is still below average for private colleges.[31]

Figure 3. University of Richmond Need-Based Aid, Pell Grant Recipients, and Net Price

Sources:

Need-Based Aid Data: University of Richmond Common Data Set.

Pell Grant & Net Price Data: IPEDS. Net price data represented in nominal terms.

Note: Data on institutional aid budget is for 2008-09 and 2013-14 because data from 2007-08 was not available. Data for share of full-time undergraduates receiving need-based aid and share of full-time, first-time undergraduates receiving Pell Grants is from 2007-08 to 2013-2014.

To fund its expanded aid budget, the University of Richmond has increased endowment support for the operating budget from 27 percent of annual operating revenue in 2007 to 34 percent in 2012, while still staying within board-approved endowment spending guidelines. This funding mechanism has allowed the institution to avoid a significant increase in either tuition or the share of full-pay students.[32]

University of Richmond engages in careful planning to ensure that its spending maximizes the enrollment and experiences of low- and moderate-income students. In 2008, for example, the University of Richmond considered extending its no-loan policy for Virginia students earning less than $40,000 per year to students from outside Virginia. Through analyses using historical admissions data, university leaders determined that such an initiative would have a high price tag while doing little to change the institution’s demographic profile. Instead, the University of Richmond invested in its “Promise for Virginians” policy, which analyses indicated would have a more substantial impact on low- and moderate-income student enrollment.[33] In 2014, leaders decided to expand the policy to cover students with incomes below $60,000.[34]

The University also thought beyond traditional financial aid programs to create the “Richmond Guarantee” in 2014. Through this program, every undergraduate student is guaranteed a university-funded fellowship of up to $4,000 to support a summer internship or faculty-mentored research project. This program makes it possible for students who would otherwise need a traditional summer job to instead have a co-curricular experience in Richmond or around the world. Over 600 students participated in 2016, gaining research and professional experience in 27 states and 21 different countries.

University of Texas at Austin

Key Takeaways

Successes

- Increased socioeconomic and demographic diversity substantially since the implementation of the Texas Ten Percent Plan in 1997, and has dedicated increasing shares of its aid budget to need-based aid.

- Increased four-year graduation rates from 50 percent in 2010 to 60.9 percent in 2016.

Challenges

- Faced state budget cuts and a limited capacity to raise tuition and fees to make up for shortfalls.

- Under the Texas Ten Percent Plan, has enrolled a diverse student body with varying levels of academic preparation.

Strategies

- Utilized one-time grants to jump-start student success efforts.

- Used predictive modeling to target and make efficient use of aid and support dollars.

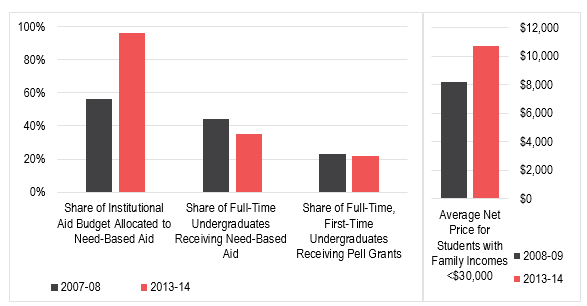

From fiscal year 2009 to fiscal year 2014, the portion of revenue provided by state appropriations at University of Texas at Austin decreased from 19 percent to 10 percent. Since 2009, the institution has also been limited in the extent to which it can rely on increased tuition and fees to make up gaps in revenue. In particular, due to a board of regents mandate, tuition and fees stayed flat from 2011-2012 to the 2016-2017 academic year.[35] The institution also operates in a unique policy environment: the Texas Ten Percent plan, enacted in 1997, guarantees admission to any public Texas institution for students in the top 10 percent of each Texas high school class. UT Austin received some flexibility from the state legislature in implementation of the Ten Percent plan in 2009, so that today the specific percentage of the high school graduating class that receives automatic admission to UT Austin is linked to an estimate of what would constitute 75% of UT Austin’s in-state admissions. Still, the Ten Percent policy has resulted in substantial increases in the number of high schools across the state that send students to UT Austin.[36] As a result of this policy and other measures, about a quarter of UT Austin students receive Pell Grants, and, in academic year 2013-2014, UT Austin spent 96 percent of its institutional aid budget on need-based aid.

Figure 4. UT Austin Need-Based Aid, Pell Grant Recipients, and Net Price

Sources:

Need-Based Aid Data: UT Austin Common Data Set.

Pell Grant & Net Price Data: IPEDS. Net price data represented in nominal terms.

While UT Austin has a strong reputation for academic excellence, with 40,000 students, the institution has not always been easy to navigate for the growing number of low-income and first-generation students it serves. Recognizing that it can only fulfill its public mission by ensuring that all of its students have the opportunity to graduate in a timely fashion, the institution committed to increasing its four-year graduation rate from 50 percent in 2010 to 70 percent by 2017. The university has made significant progress since announcing the goal: the four-year graduation rate had increased to 60.9 percent in 2016.[37]

To pursue its student success goals while navigating complex budgetary constraints, UT Austin has relied on a sophisticated use of predictive analytics to target its resources. On the budgetary side, the university has used analytics to inform administrative streamlining initiatives, staffing reductions, and facilities management that have freed up funds for need-based financial aid and other student-focused programs.[38] UT Austin has also thoroughly analyzed its own historical data to help identify students most in need of support and the best ways to support them.

Informed by this analysis, UT Austin has designed an array of intensive support programs, particularly for first-year students in its largest colleges. Students are assigned to one of these student success programs based on their likelihood of four-year graduation, considering their pre-college characteristics.[39] The programs are designed to reflect current research on early-college experiences that are most likely to lead to student persistence and success. The students who are most at risk and have financial need are also assigned to an incentive-based scholarship and leadership program called the University Leadership Network (ULN). ULN students receive scholarships paid out monthly that are linked to academic and co-curricular performance measures.[40] A new database also allows administrators to track student outcomes by program so they can target outreach and ensure that support programs are effective.[41]

UT Austin has also excelled at procuring and making effective use of one-time grants. For example, in 2012, the UT System Regents made a one-time allocation of about $85 million for academic development programs and student success initiatives, of which only about $3.9 million was discretionary.[42] The Provost’s office used these funds to help seed student success programs within colleges. UT Austin is currently evaluating how to continue funding and refining these student success initiatives.[43] The school is also focused on developing innovative educational pipeline initiatives, new degree program designs that include expanded experiential learning opportunities, and improved career and job placement services for current students and recent graduates.

Vassar College

Key Takeaways

Successes

- Increased the share of students receiving Pell grants from 7 percent in 2006-2007 to 22 percent in 2013-2014.

- Maintained need-blind admissions and full-need financial aid policies throughout periods of financial constraint.

Challenges

- Had to limit endowment draw during the Great Recession, which required budget cuts in other areas to maintain aid policies.

Strategies

- Used peer comparisons to identify areas in which it could cut costs to increase need-based aid.

- Increased financial aid budget by committing a larger share of endowment earnings, deferring capital projects, and making temporary staffing cuts.

- Phased in changes and reallocations gradually over the course of several years.

- Built a reputation as a leader in efforts to expand opportunity, earning recognition and monetary awards.

For Vassar College, the Great Recession came right on the heels of an intensification of the institution’s commitment to socioeconomic diversity. In 2007, then-president Catharine Bond Hill reintroduced a need-blind admissions policy to supplement Vassar’s established commitment to full-need financial aid. Additionally, in 2008 the board endorsed a proposal to eliminate loans for students with family incomes less than $60,000.[44] With these policies and intensive recruitment, Vassar tripled the share of its new freshman who received Pell grants from 7 percent to 22 percent between 2006-2007 and 2013-2014. In 2014, the six-year graduation rate for first-time, full-time students who received Pell Grants was 92.9 percent, slightly higher than the share of non-Pell students who graduated within six years, which was 92.2 percent.[45]

Like many other institutions, Vassar’s endowment shrunk significantly after 2008, and, to complicate matters, Vassar’s board of trustees had already asked that the institution limit its endowment draw to 5 percent.[46] While Vassar could have rescinded its commitment to no-loans and full-need aid (as several other institutions did during the Great Recession), it maintained those policies and continued to recruit low- and moderate-income students. Between 2007-2008 and 2012-2013, Vassar was also able to keep the average net price under $6,000 for students from families earning less than $48,000 per year and under $5,000 for those from families earning less than $30,000 per year (net price grew to around $10,000 for these groups in 2013-2014, due in part to enrolling a cohort of veterans, whose federal stipend factors into net price calculations differently than other students’ financial aid). These efforts required the school to increase its need based-aid budget from $42 million to $58 million, and the amount of aid that came from institutional sources increased from $26.3 million in 2006-07 to $57.8 million in 2014-15.[47]

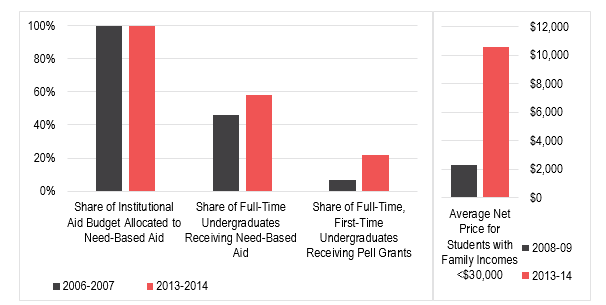

Figure 5. Vassar College Need-Based Aid, Pell Grant Recipients, and Net Price

Sources:

Sources:Sources:

Need-Based Aid Data: Vassar College Common Data Set and annual Factbook.

Pell Grant & Net Price Data: IPEDS. Net price data represented in nominal terms.

Since the Great Recession restricted Vassar’s ability to draw from its endowment, an increasing portion of the institutional aid budget came from unrestricted funds and reallocations.[48] To identify cost-savings that could yield additional revenue for financial aid, Vassar analyzed its expenditures in relation to institutional peers and found that its staffing compensation costs were relatively high.[49] As a result, Vassar established a multi-year plan that included temporary salary freezes and overtime reductions, and permanent staffing reductions through retirement incentives, contingent faculty reductions, and not filling open positions.[50] Hill was transparent in communicating with the Vassar community about these cuts, emphasizing the institution’s commitment to increasing opportunity to ensure support.[51]

Since the economy has stabilized, Vassar has not had to rely on staffing cuts to support aid; instead, it has maintained need-based aid as priority in its budgeting process, slowed capital expenditures, used endowment funds, and dedicated money from fundraising campaigns to need-based aid.[52]

Like many of the institutions profiled in this report, Vassar has made its commitment to opportunity a core component of its institutional culture and public image. Hill has emerged as a leader in the public dialogue about socioeconomic diversity at selective institutions, and Vassar has been recognized widely for its efforts.[53] This self-conception and public image have helped the community buy into sometimes difficult financial decisions, and the broad recognition has enhanced Vassar’s reputation and increased the size and quality of its applicant pool.[54]

Conclusion

If given the opportunity, talented low- and moderate-income students can thrive at high-performing colleges and universities. These institutions can open the door wider to students of all backgrounds and, as institutions that receive support from the public sector, have a responsibility to do so. However, making this commitment requires that institutions engage in new practices and make new financial commitments.

There are a number of selective colleges and universities that have enhanced their efforts to promote opportunity despite significant financial constraints. In each case, strategic cost containment to reallocate funds to financial aid and supports for low- and moderate-income students have been critical. Such tradeoffs require strong leadership, an engaged community, and strategic plans for managing change. At each of the schools that we profiled, leaders and change-makers have visibly committed to the goal of increasing opportunity, have analyzed data to ensure operations and deployment of aid are efficient, and have used tactics such as gradual budgetary changes to deepen stakeholder buy-in. While there have been bumps in the road, for the most part, these strategies have enabled the profiled institutions to reallocate funds in ways that are financially sustainable, maximally effective, and broadly supported.

Endnotes

- Data from IPEDs, based on an analysis of total undergraduates receiving Pell Grants and total number of undergraduates as reported on the student financial aid component for academic year 2013-2014 for 2,386 four-year public and four-year private non-profit institutions. Our focus in this paper is on students in the lower half of the income distribution. Because there is limited, publicly available data on family income by college, we use data on Pell Grant recipients as a proxy. Students who receive Pell Grants are generally in the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution. A group of economists, working with data from the Internal Revenue Service, recently published analysis and datasets on the distribution of family incomes of students at thousands of US colleges and universities. See Raj Chetty, John N. Friedman, Emmanuel Saez, Nicholas Turner, Danny Yagan, “Mobility Report Cards: The Role of Colleges in Intergenerational Mobility,” The Equality of Opportunity Project (January 2017), http://www.equality-of-opportunity.org/papers/coll_mrc_paper.pdf. However, these data are available only for students who entered college in 2009 and earlier. Because that is early in the period of focus for the institutions profiled in this paper, we rely on the less nuanced Pell Grant data instead. ↑

- See, for example, the literature on undermatching: Caroline Hoxby and Christopher Avery, “The Missing ‘One-Offs’: The Hidden Supply of High Achieving, Low-income Students,” Brookings Institution (2013), https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-missing-one-offs-the-hidden-supply-of-high-achieving-low-income-students/; Caroline Hoxby and Sarah Turner, “Expanding College Opportunities for High-Achieving, Low-income Students,” Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (December 2014), http://siepr.stanford.edu/?q=/system/files/shared/pubs/papers/12-014paper.pdf. For financial challenges, see Catharine B. Hill, Gordon C. Winston and Stephanie A. Boyd, “Affordability: Family Incomes and Net Prices at Highly Selective Private Colleges and Universities,” The Journal of Human Resources, 40 (2005): 4, 769-790, http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED485536.pdf; Paul Tough, “Who Gets to Graduate,” The New York Times Magazine (May 15, 2014), http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/18/magazine/who-gets-to-graduate.html. ↑

- See, for example, Susan Dynarski, “Does Aid Matter? Measuring the Effects of Student Aid on College Attendance and Completion,” American Economic Review 93(2003): 1, 279–288, http://www.nber.org/papers/w7422; Thomas J. Kane, “A Quasi-Experimental Estimate of the Impact of Financial Aid on College-Going” National Bureau of Economic Research, (No. w9703: 2003), http://www.nber.org/papers/w9703; Neil Seftor and Sarah Turner, “Back to School: Federal Student Aid Policy and Adult College Enrollment,” Journal of Human Resources 37 (2002): 2, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3069650?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents; Eric Bettinger, “How Financial Aid Affects Persistence,” in College Choices: The Economics of Where to Go, When to Go, and How to Pay for It, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 207-238; Sara Goldrick-Rab, Doug Harris, Robert Kelchen, and James Benson, “Need-Based Financial Aid and College Persistence Experimental Evidence from Wisconsin,” SSRN 1887826 (2012); Benjamin L. Castleman and Bridget Terry Long, “Looking Beyond Enrollment: The Causal Effect of Need-Based Grants on College Access, Persistence, and Graduation,” National Bureau of Economic Research, No. w19306 (2013) http://www.nber.org/papers/w19306. ↑

- See Mamie Lynch, Jennifer Engle, and Jose L. Cruz, “Priced Out: How the Wrong Financial Aid Policies Hurt Low-Income Students,” The Education Trust (June 2011), http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED520199.pdf. See also Stephen Burd, “Undermining Pell: How Colleges Compete for Wealthy Students and Leave the Low-income Behind, Volume II,” New America Foundation (2014), http://www.edcentral.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/UnderminingPellVolume2_SBurd_20140917.pdf. ↑

- Data from the Education Trust’s Pell Partnership Online Data Tool, available at: https://edtrust.org/resource/pellgradrates/#anchor. For an analysis of the graduation gap between Pell and non-Pell students, see Andrew Howard Nichols, “The Pell Partnership: Ensuring a Shared Responsibility for Low-Income Student Success,” The Education Trust (September 2015), https://edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/ThePellPartnership_EdTrust_20152.pdf. For calculation methods, see Andrew Howard Nichols, “The Pell Partnership: Ensuring a Shared Responsibility for Low-Income Student Success-Methods and Data Collection,” The Education Trust (September 2015), https://edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/MethodsDataCollection_ThePellPartnership_EdTrust_2015.pdf. National average, six-year graduation rates are about 60 percent. See “Fast Facts: Graduation Rates,” National Center for Education Statistics, https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=40. ↑

- Peter Durantine, “F&M’s President Porterfield Named for a White House ‘Champion of Change for College Opportunity,’” Franklin & Marshall College (September 27, 2016), http://www.fandm.edu/news/latest-news/2016/09/27/f-m-s-president-porterfield-named-a-white-house-champion-of-change-for-college-opportunity . ↑

- Franklin & Marshall Common Data Sets and IPEDS. See also “Posse Program: STEM Cohort, Franklin & Marshall College,” Building Blocks to 2020: First in the World Competition (January 2014), http://www.naicu.edu/special_initiatives/2020/detail/posse-program-stem-cohort-2. Franklin & Marshall financial aid website, http://www.fandm.edu/financial-aid/financial-aid-resources; some data provided by Franklin & Marshall. ↑

- The Posse Foundation identifies public high school students who may be overlooked by the traditional college selection process, places them into a supportive, multicultural team, and partners with colleges and universities to cover full tuition for four years. See “Mission + History + Goals,” The Posse Foundation, Inc., http://www.possefoundation.org/about-posse/our-history-mission. ↑

- Daniel Porterfield, “STEM Education Breakout Session, White House College Opportunity Day of Action,” Franklin & Marshall Office of the President: Speeches & Remarks (December 2, 2014); Daniel Porterfield, “Widening the STEM Pipeline: An American Imperative,” Franklin & Marshall Office of the President: Speeches & Remarks (September 22, 2014). ↑

- Data provided by Robyn Piggott at Franklin & Marshall. The school maintains a very small portion of merit only aid, drawn from restricted endowment scholarships. These total up to less than $10,000 for incoming students. ↑

- See “2014 Annual Report of Giving,” Franklin & Marshall College (June 30, 2014), http://www.fandm.edu/arg, and “Capital Campaign Announcement,” Office of the President: Messages to the Community (May 12, 2014), http://www.fandm.edu/president/messages-to-the-community/capital-campaign-announcement. ↑

- For more on Franklin & Marshall’s partnerships with these organizations, see “The Next Generation Initiative at Franklin & Marshall College,” Franklin & Marshall College (accessed January 11, 2017), https://www.fandm.edu/uploads/files/235892126248521114-2014factsheet-nextgen2-27-15.pdf. ↑

- Support services that help all students include an Office for Student and Post-Graduate Development, intensive writing courses, a new math and science center, and the College House system that replaces the traditional dormitory model with a family like environment. See Jason Klinger, “Expert on Student Outcomes to Guide Franklin & Marshall Efforts,” F&M News (June 21, 2012), http://www.fandm.edu/news/latest-news/expert-on-student-outcomes-to-guide-franklin-marshall-efforts, and Daniel Porterfield, “Widening the STEM Pipeline: An American Imperative,” Franklin & Marshall Office of the President: Speeches & Remarks (September 22, 2014). ↑

- Since 2008, the average SAT scores, average high school GPAs, and first-year retention rates of Franklin & Marshall’s freshman class have remained steady and applications have grown, while Pell Grant recipients have earned comparable GPAs and retained at higher rates than their entering cohort as a whole. See Daniel Porterfield, “Expanding Access and Opportunity: Lessons Learned from Private Colleges,” presentation at the Urban Institute (February 23, 2015), provided by President Porterfield. For Pell graduation rates, see Andrew Howard Nichols, “The Pell Partnership: Ensuring a Shared Responsibility for Low-Income Student Success.” ↑

- This represents a 4 percent increase in nominal value since academic year 2008-2009. Data from U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System and provided by Brit Moller, Brit Moller, Assistant Director of State Government Relations at UC Berkeley. UC Berkeley educates as many Pell eligible students as the entire Ivy League combined. ↑

- Information provided by Brit Moller. For Pell graduation rates, see Andrew Howard Nichols, “The Pell Partnership: Ensuring a Shared Responsibility for Low-Income Student Success.” Data for birth cohorts from 1980 to 1991 show that 15 to 20 percent of UC Berkeley undergraduates have come from the bottom two income quintiles. This is a higher share than is served by any of the other profiled schools, as well as by most selective public institutions. See Chetty, et al, “Mobility Report Cards.” ↑

- Overall, state funding for California higher education was reduced 29.3% from 2008 to 2013. By comparison, state funding for Texas schools was cut by 22.7% and funding for North Carolina schools was cut by 14.6%. See Phil Oliff, Vincent Palacios, Ingrid Johnson, and Michael Leachman, “Recent Deep State Higher Education Cuts May Harms Students and the Economy for Years to Come,” The Center for Budget and Policy Priorities (March 19, 2013), http://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=3927. ↑

- Information provided by Britt Moller. See also Daniel de Vise, “UC Berkeley and Other ‘Public Ivies’ in Fiscal Peril,” The Washington Post (December 26, 2011), http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/uc-berkeley-and-other-public-ivies-in-fiscal-peril/2011/12/14/gIQAfu4YJP_story.html; see also “2013-14 UC Berkeley Budget Plan,” Campus Budget Office (September 2013), http://cfo.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/2013-14%20UC%20Berkeley%20Budget%20Plan%20-%20Final%20(9-5-13).pdf; “The facts: UC Budget Basics,” University of California Communications (March 6, 2013), https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/sites/default/files/thefacts_budgetbasics_0313.pdf. ↑

- See 2007-2008 and 2012-2013 Registration Fees, UC Berkeley Office of the Registrar, https://registrar.berkeley.edu/tuition-fees-residency/; “University of California, Berkeley: Annual Financial Report 2007-08,” UC Berkeley Controller’s Office (2008), https://controller.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/2007-08_financial.pdf; “2012-14 UC Berkeley Budget Plan,” Campus Budget Office (September 2012), https://cfo.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/BerkeleyBudgetPlan2012-13.pdf. ↑

- See Katy Murphy, “UC to Cap Out-of-State Students at Berkeley, UCLA,” San Jose Mercury News (March 4, 2015), http://www.mercurynews.com/california/ci_27634630/uc-cap-out-state-students-at-berkeley-ucla. ↑

- See Lilia Vega, “The History of UC Tuition Since 1868,” The Daily Californian (December 22, 2014), http://www.dailycal.org/2014/12/22/history-uc-tuition-since-1868/. ↑

- From 2007-08 to 2012-13, the share of total aid given to all UC Berkeley students in institutional funds (restricted and unrestricted) grew from 67% to 75%. In comparison, the share of aid awarded through state and federal grants decreased from 21% to 13%, and non-Pell federal grants remained steady at 12%. Data from U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. ↑

- “Innovative Berkeley Aid Programs,” UC Berkeley Financial Aid & Scholarships, http://financialaid.berkeley.edu/innovative-berkeley-aid-programs. Though aid comes from a variety of sources, the majority is drawn from institutional funds. From 2007-08 to 2012-13, the share of total aid given to all UC Berkeley students in institutional funds (restricted and unrestricted) grew from 67% to 75%. In comparison, the share of aid awarded through state and federal grants decreased from 21% to 13%, and non-Pell federal grants remained steady at 12%. Data from U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. ↑

- See “University of California Admits Significantly More California Freshman Students, Makes Gains in Diversity,” UC Office of the President (April 4, 2016), http://universityofcalifornia.edu/press-room/university-california-admits-significantly-more-california-freshman-students-makes-gains. ↑

- This includes $40 million in annual savings in fiscal year 2014. See “Progress Report: April 15,” Operational Excellence Program Office (April 2015), http://vcaf.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/2015ProgressReport_final_web.pdf. For the Bain & Co. final report, see “Achieving Operational Excellence at University of California, Berkeley,” Bain & Company (April 2010), http://oe.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/diagnostic%20report%20bain%20uc%20berkeley.pdf, UC Berkley’s 2014 budget was $2.14 billion in 2014. See “2013-2014 UC Berkeley Budget Plan.” ↑

- For staffing cuts, see U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. “Revenue Generation,” UC Berkeley Operational Excellence. To date, four projects have been approved through this initiative, and UC Berkeley’s Office of Planning and Analysis estimates that these projects will generate $6.5 million in net revenue within five years. ↑

- Notes from conversation with Nanci Tessier, March 27, 2015. See also the University of Richmond’s Common Data Sets, available at http://ifx.richmond.edu/research/common-data.html. ↑

- “The Richmond Promise: Principle III—Access & Affordability,” available at https://strategicplan.richmond.edu/access/index.html. ↑

- U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. ↑

- University of Richmond’s Common Data Sets. ↑

- According to research conducted by Stephen Burd, in the 2013-2014 school year, there were only 25 private nonprofit colleges at which Pell Grant recipients made up more than 15 percent of enrolled students that had average net prices for the lowest-incomes students under $10,000. Most private, nonprofit institutions charge low-income students well over $10,000. See Stephen Burd, “Undermining Pell: Volume III,” New America Foundation (March 2016), https://static.newamerica.org/attachments/12813-undermining-pell-volume-iii/Undermining-Pell-III-3.15bba9018bb54ad48f850f6f3a62a9fc.pdf. ↑

- See University of Richmond’s Common Data Set. ↑

- Conversation with Nanci Tessier, Vice President for Enrollment Management, on March 27, 2015. ↑

- Nicole Cohen, “Cutting Costs,” Richmond Magazine (September 11, 2013), http://richmondmagazine.com/life-style/cutting-costs-09-11-2013/. ↑

- Tuition and fees will increase at most UT schools for the 2017-2016 school year. Lauren McGaughy, “Regents Approve Tuition Increase at UT-Dallas, UT-Austin,” Dallas News (February 29, 2016). State funding has gone from comprising nearly half of UT Austin’s budget, to comprising only 12 percent of operating revenues in 2014-2-15. See “Why We Need Your Support,” University of Texas at Austin, https://education.utexas.edu/support-college/; Matthew Watkins, “Hutchison, Fenves Decry Dwindling State Support for Higher Education,” The Texas Tribune (April 11 ,2016), https://www.texastribune.org/2016/04/11/hutchison-fenves-decry-dwindling-state-support-hig. ↑

- The Texas Ten Percent Plan was likely a cause of an increase in the share of entering UT Austin students from the bottom two income quintiles from 11.9 percent in 1998 to 15.2 percent in 2009. See Chetty, et. al, “Mobility Report Cards.” ↑

- “Graduation Rates, Applications and Incoming Class Set Records at UT Austin,” UT News (September 19, 2016), http://news.utexas.edu/2016/09/19/graduation-rates-applications-incoming-class-set-records. ↑

- In fiscal year 2011, UT Austin cut approximately 200 positions in response to a 5 percent budget reduction, and in fiscal year 2013, the school cut approximately 400 positions to deal with $92 million reductions in state general revenue funding. Through Transforming UT, an operational efficiency initiative, UT Austin plans to leverage existing assets, encourage innovation, and reorganize certain administrative functions through a shared services model, and has projected savings of up to $490 million over a decade. See “The University of Texas System: Operating Budget Summaries and Reserve Allocations for Library, Equipment, Repair and Rehabilitation and Faculty Stars: Fiscal Year 2012,” The University of Texas System (2011), https://www.utsystem.edu/sites/default/files/news/assets/fy2012-budget-summaries.pdf. For information on Transforming UT, see Steve Rohleder, “Smarter Systems for a Greater UT: Final Report of the Committee on Business Productivity,” University of Texas at Austin Office of the President (January 2013), and the Transforming UT website at https://www.utexas.edu/transforming-ut. ↑

- Paul Tough, New York Times Magazine, May 18, 2014. ↑

- Harrison Keller, Vice Provost of Higher Education Policy and Research, and Katie Brock, Associate Director of the Center for Teaching and Learning, University of Texas at Austin, during a conversation on March 31, 2015. ↑

- In addition to the graduation model, UT Austin’s data team is in the process of developing a post-matriculation model that predicts the probability of four-year graduation based on their academic performance and extracurricular activities for students already enrolled in the university. This would provide staff and faculty with real-time data on whether a student is on track to graduate, which could then be used to generate alerts to advisors if students are found to be off-track. ↑

- “UT System Regents Approve $13.1 Billion Operating Budget,” The University of Texas System, August 25, 2011, http://www.utsystem.edu/news/2011/08/25/ut-system-regents-approve-131-billion-operating-budget. ↑

- “The University of Texas System: Operating Budget Summaries and Reserve Allocations for Library, Equipment, Repair and Rehabilitation and Faculty Stars: Fiscal Year 2015,” The University of Texas System (2014), https://www.utsystem.edu/sites/default/files/documents/controller/operating-budget-system-administration-fy-2015/fy15budgetsummaries.pdf. ↑

- See “Cooke Foundation Awards Vassar College Inaugural $1 Million Prize for Supporting High-Performing, Low-Income Students,” Jack Kent Cooke Foundation (April 7, 2015), http://www.jkcf.org/cooke-foundation-awards-vassar-college-inaugural-1-million-prize-for-supporting-high-performing-low-income-students/. ↑

- In 2015, these two rates were once again fully equal for a second consecutive year: 90.3% and 90.4% respectively. Information provided by David Davis Van Atta at Vassar’s Office of Institutional Research. ↑

- Information provided by David Davis Van Atta at Vassar’s Office of Institutional Research. ↑

- Aid data from the Vassar College Factbook, 2015/16, http://institutionalresearch.vassar.edu/docs/VassarFactbook201516.pdf. Pell Grant data is from U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. Need-based aid data is from Vassar’s Common Data Sets for 2009-2010 and 2014-15, available at http://institutionalresearch.vassar.edu/data/2009-2010/h-financial-aid.html. For more on Vassar’s affordability, see “Vassar Tops New York Times Report on Enrollment of Lower Income Students at Leading Colleges,” Vassar Office of Communications (September 9, 2014), http://info.vassar.edu/news/announcements/2014-2015/140909-nytimes-report%20.html. Vassar has also increased racial diversity and the number of first generation students enrolled through these efforts. See Kerry Hannon, “At Vassar, a Focus on Diversity and Affordability in Higher Education,” New York Times (June 22, 2016), http://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/23/education/at-vassar-a-focus-on-diversity-and-affordability-in-higher-education.html. ↑

- In academic year 2007-2008, endowment funds ($9.4 million) comprised 30% of all aid provided by institutional resources given to Vassar undergraduates ($30.7 million), while general funds made up 68% ($21 million). By contrast, for academic year 2015-2016, endowment funds made up 22% (13.8 million) of all aid from Vassar sources (61.7 million), while general funds made up 77% ($47.4 million). See Vassar College Factbook 2015/2016, http://institutionalresearch.vassar.edu/docs/VassarFactbook201516.pdf. ↑

- For example, in 2008, Vassar’s student to clerical staff ratio was only 10.4:1 and service and maintenance staff to student ratio was 8.3:1. By comparison, the average student to clerical staff ratio at Vassar’s 21 primary reference institutions was just under 14:1, and the average student to service staff ratio was just above 10:1. See Vassar College Factbook 2015/2016, http://institutionalresearch.vassar.edu/docs/VassarFactbook201516.pdf. ↑

- Vassar has cut clerical staffing by 14.3% and service and maintenance staffing by 7.3% since 2008. In fall 2013, the student to clerical staff ratio was 13.8:1 and the student to maintenance staff ratio was 9.8:1. In 2014, Vassar achieved a permanent net reduction of 30 full-time employees through buy-out retirement incentives. See Vassar College Factbook 2015/2016, http://institutionalresearch.vassar.edu/docs/VassarFactbook201516.pdf. ↑

- See President Catharine Hill’s letters on Vassar and the Economy, http://economy.vassar.edu/letters/. ↑

- Email from President Catharine Hill, March 20, 2015. ↑

- See, for example “Cooke Foundation Awards Vassar College Inaugural $1 Million Prize for Supporting High-Performing, Low-Income Students,” Jack Kent Cooke Foundation (April 7, 2015), http://www.jkcf.org/cooke-foundation-awards-vassar-college-inaugural-1-million-prize-for-supporting-high-performing-low-income-students/. Vassar was recognized as #1 on the New York Times’ 2014 index of most socioeconomically diverse top colleges. In 2015, it was ranked number eight (changes due mostly to alterations in the selection and ranking criteria), and was the top private school on the list. ↑

- The number of freshman applicants at Vassar grew from 6,075 for the class of 2010 to 7,567 for the class of 2019. Since the implementation of the 2400 point SAT with the class of 2012, average SAT scores among Vassar freshman have increased slightly from 2086 to 2101. See the Vassar College Factbook 2015-2016, Vassar College, http://institutionalresearch.vassar.edu/factbook/.board ↑

Attribution/NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of the license, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.